Over the next 20 years the number of adults aged 65 and over are expected to nearly double, growing from 12% to 20% of the U.S. population (Institute of Medicine, 2008). This increase in older adults will produce new and challenging demands on existing health care systems. Adults over the age of 65 currently account for 65% of hospital stays (Mezey, Boltz, Esterson, & Mitty, 2005), have four times the number of hospital admissions when compared to adults younger than 65 years (Administration on Aging, 2004), account for 26% of all physician office visits, 38% of emergency room visits, 85% of home health care visits, and 90% percent of nursing home use (Bednash, Fagin, & Mezey, 2003; Institute of Medicine, 2008; Plonczynski, Ehrlich-Jones, Robertson, Rossetti, Munroe, & Koren, 2007). These percentages are projected to increase as the population ages (Institute of Medicine, 2008).

Nurses have been identified as a key health care provider best positioned to meet the increasing demands placed on the health care system by an aging society (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Leaders in gerontological nursing have long recognized the increasing demands for nursing care of the aged and have responded by changing the way students are exposed to gerontological education during their nursing program. One of the goals of gerontological leaders has been to increase the number of nurse graduates who have positive attitudes towards older adults and intend to work with older adults upon graduation. Common strategies used to improve student nurse attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults have been focused on clinical placements and on incorporating gerontological content as either as a stand-alone course or integrated content throughout the nursing program (Blais, Mikolaj, Jedlicka, Strayer, & Stanek, 2006; De La Rue, 2003; Fagerberg, Winblad, & Ekman, 2000; Greenhill & Baker, 1986; Happell, 2002; Hancock, Helfers, Cowen, Letvak, Barba, & Herrick, 2006; Holroyd, Dahlke, Fehr, Jung, & Hunter, 2009; Sheffler, 1995; Snape, 1986; Williams, Anderson, & Day, 2007).

A number of studies have focused on understanding whether these educational strategies have successfully improved attitudes or preferences. Results across studies have been inconsistent and unclear regarding the role educational strategies have had in changing attitudes or preferences over time. Similar educational strategies have been linked to both improvements and deteriorations in attitudes. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that even in cases where students have positive attitudes, they generally still prefer to not work with older adults or in nursing homes. There is a serious shortage of caregivers with an interest in caring for older adults. Given the projected increase in older adults who will need care outside the hospital, it is critical that we identify barriers to selecting work settings where the majority of older adults will be receiving care. Research that provides insight into the development of attitudes and preferences of student nurses about care of older adults and work setting will be necessary if we are to develop effective strategies to expand this much needed work force. Understanding how attitudes and preferences change over time and how new graduates make choices about where they will work is vital. To further explore the role of geronotological education strategies in changing nursing students’ attitudes toward and preference to work with older adults, a longitudinal mixed methods study was conducted with undergraduate nursing students in southern Wisconsin. The purpose of this exploratory study was to 1) describe how student nurse attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults changed over time and 2) gain insight into the possible ways the students’ education influenced these trends.

Background

Interest in capturing and understanding student nurse attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults can be traced back several decades (Gunter, 1971; Hart, Freel, & Crowell, 1976; Kayser & Minnigerode, 1975; Shimamoto & Rose, 1987; Treharne, 1990). Studies have focused on evaluating student nurse trends in a) attitudes alone, b) preferences alone, or c) both attitudes and preferences toward working with older adults.

Attitudes

Studies of student attitudes have generally shown that attitudes toward older adults move in three directions, from negative to positive, positive to less positive, and no change at all over the course of the nursing curricula (Blais, Mikolaj, Jedlicka, Strayer, & Stanek, 2006; De La Rue, 2003; Greenhill & Baker, 1986; Hancock et al., 2006; Snape, 1986; Williams, Anderson, & Day, 2007).

Several studies of student nurse attitudes have shown a positive change in attitude during the nursing program, specifically after both clinical experiences and theoretical gerontological content. Sheffler (1995) examined nursing student attitudes towards older adults before and after students’ clinical experiences in two different health care settings. Results from this study found that students’ attitudes improved, but this improvement occurred regardless of the setting. Jansen (2004) evaluated student attitudes before and after two different methods of gerontological nursing curricula; specifically a stand-alone course and an integrated format throughout the nursing program. The authors found that attitudes improved significantly, but did so similarly after each type of gerontological content offerings.

Other researchers have found that student attitudes became less positive during the course of a nursing program, again both in relation to clinical and theoretical experiences. Haight and colleagues (1994) examined the attitudes of 118 baccalaureate nursing students over a three year time period. The authors found that students’ attitude scores became less positive as clinical experiences with more critically ill older adults increased. Holroyd and colleagues (2009) found similar results. The authors conducted a cross sectional study of 197 nursing students. Results from the study found a drop in positive attitudes and a rise in negative attitudes at the beginning of year two and year four of the nursing program. The authors indicated that during the time period in which the sampling occurred, students had considerable exposure to complex older adults.

Finally, other studies of student nurse attitudes have found no change in attitudes over time. Koren (2008) conducted a cross sectional survey of all nursing students enrolled in a nursing program. Two hundred students participated. Participants represented all five semesters of the program. Gerontological nursing content was integrated throughout the program. Koren found that students’ attitudes towards older adults remained relatively neutral throughout the course of the nursing program even though knowledge of aging and confidence working with older adults increased. The author further stated that semester placement in the program did not predict attitudes towards older adults, in fact semester placement only accounted for 3 percent of the variance in attitudes.

Preferences

Some researchers have chosen to explore students’ intentions to work with, or preferences for working with older adults, rather than explore attitudes. These studies have repeatedly shown students prefer not to work with older adults or work in nursing home settings. Moyle (2003) conducted a cross sectional survey of work preference of undergraduate nursing students. Students were asked if they were interested in working in a long term care setting and what would change their minds about working in long term care. Ninety-seven percent of respondents indicated they had no intention of working in long term care. Students saw the environment as a depressing place where everyone was dying. Despite this, students did indicate that a more favorable view of long term care, a greater understanding of what long term care is, and improved working conditions such as reducing the physical nature of the work would entice them into considering long term care as a career option. Students’ lack of preference to work with older adults was also found by Happell (1999). The author conducted a mixed methods study and found that students ranked working with the elderly lowest among nine choices of work settings and populations. In interviews, Happell found that students saw working with the elderly as boring, unchallenging, and uninteresting.

McCann(2010) and Kloster (2007)conducted longitudinal studies of student work preferences. Each of these studies primarily focused on understanding the settings students wanted to work in after graduation. These researchers found that student career preference for acute care settings consistently increased over the course of the nursing programs while preference for aged care remained last. The authors indicated that student career preference may be related to theoretical and clinical emphasis of the nursing curriculum.

Attitudes and Preferences

Other studies have investigated whether positive attitudes are related to or influence student preferences to work with older adults upon graduation. Results from these studies have found that although student attitudes are generally positive, they have no interest in working with older adults upon graduation (Briscoe, 2004; Fagerberg, Winblad, & Ekman, 2000; Happell, 2002; Henderson, Xiao, Siegloff, Kelton, & Paterson, 2008).

Briscoe (2004) conducted a study to investigate whether a difference existed between two methods of teaching gerontology with respect to students’ knowledge, attitudes, and intentions to work with older adults. Results from this study showed that there was no significant difference between methods in relation to knowledge. In addition, attitudes were generally positive in both methods and students in both programs rated working in long-term care as the least preferred choice of work setting upon graduation.

Fagerberg and colleagues (2000) conducted a longitudinal qualitative study of students’ preferred work areas. The researchers found that although students expressed positive attitudes towards older adults, they were reluctant to work in long term care settings. Students viewed long term care as too slow of a pace, monotonous, and physically demanding. In addition the setting was seen as isolating and with no support system for new graduates.

Happell (2002) conducted a study that examined attitude and preference. Student preferences for work in nine practice areas that included both preferences for work setting (e.g. medical units) and age group (e.g. older adults) were ranked. In addition, Happell explored students’ reasons for ranking their career options. Results from the study indicate that although students’ attitudes toward older adults improved, they preferred working with older adults least of the nine practices areas. Students felt work with older adults was boring, frustrating or unpleasant. Students also expressed fear of and discomfort about working with older adults, concerns about dealing with death and dying, and concerns that older adults will not get better.

Henderson and colleagues (2008) surveyed first year students at the commencement of their program to determine their attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults. Results of the study found that students generally had positive attitudes toward older adults. However, when ranking a mix of work settings and populations, students preferred working with older adults least. Students indicated their lack of interest was related to lack of excitement, a fear of dying and suffering, and prior negative experiences with older adults. The authors indicated that there was evidence from the qualitative data that students equated working with older adults with work in long term care.

Methods

Purpose and Rationale

The purpose of the present study is to further describe and explain the role of nursing education on changing attitudes and preferences. A longitudinal mixed methods design was used to explore the following questions:

How do student nurse attitudes toward older adults change over the course of a nursing program?

How do student nurse work preferences for age group (e.g. older adults) and work setting (e.g. nursing home) change over the course of a nursing program?

What aspects of the nursing curriculum do students identify as changing their attitudes or preferences?

The first phase of the study was a quantitative analysis of attitude and preference change over time and answered the first two research questions. The second phase of the study was a qualitative exploration of the educational factors students felt may have influenced their attitudes and preferences toward older adults to change, as indicated by the first study phase.

Participants & Setting

A convenience sample (n=80) of undergraduate nursing students was recruited for the study at a large Midwestern University. The only inclusion criterion for this study was status as a nursing student enrolled in the first semester (junior year) of the baccalaureate nursing program.

Nursing Program

Students enter into the nursing program at the beginning of their junior year. A stand-alone gerontological nursing course is offered in the first semester of the senior year. Students complete two instructor-led clinical rotations in their junior year where they may have exposure to well-elderly. Review of the curriculum indicates that only half of the students are exposed to care of healthy older adults. In the senior year, students complete an individual, preceptor-led clinical rotation. Students rank their preference for clinical rotation among 60-75 possible sites, which are predominantly acute care settings; only three of the seventy five possible sites are nursing home facilities.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires were used to measure attitudes toward older adults and preferences for working with older adults. In addition, demographic information was collected from each of the students.

The Kogan Attitudes Toward Older Adults Scale (Kogan) was used to measure attitudes toward older adults (Kogan, 1961). Kogan (1961) used Spearman Brown split half reliability to establish reliability of items created for his scale. Positive items obtained correlation coefficients from .66-.77 and negative items achieved correlation coefficients of .73-.83. Pearson product-moment coefficients between positive and negative items ranged from .46-.52 demonstrating internal consistency among test items. The Kogan consists of 34 items, half of which are negatively worded and half which are positively worded. As an example, one item asks whether one agrees or disagrees to “It is foolish to claim that wisdom comes with old age.” The items are in a 6 point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree to strongly agree.” Negative items were reverse coded in the analysis so that total scores could range from 0 – 204 with 204 being extremely positive.

Based on a review of the literature, a survey was created by the researchers to measure work site and age group preferences of students. Prior studies have explored students’ order of preference across nine areas of nursing practice, which represent various work settings and populations as a reliable and valid measure of nursing student preference for patient population and work setting (Briscoe, 2004; Happell, 2002; Stevens and Crouch, 1998). Consistent with Happel's (2002) and Briscoe's (2004) study, students were asked to rank preferences for both work setting (1-10) and age group (1-7). Work settings included; home/community, nursing home/long term care, step down, intensive care, emergency room, pediatrics, obstetrics, psychiatric, medical or surgical. Age groups included; newborns, infants/children, adolescents, young adults, adults, adults 65-85 years, or adults over 85.

A demographic questionnaire included items about student's age, race, and gender.

Procedure

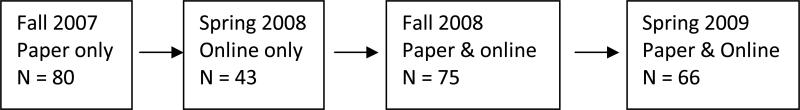

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. The questionnaires were distributed to participants at four time points during their undergraduate nursing program: Time 1-beginning of first semester junior year, Time 2-end of second semester junior year, Time 3-beginning of first semester senior year and Time 4-end of second semester senior year (Figure 1). At Time 1, a paper and pencil version of the survey was conducted. At Time 2, an online version was offered in order to make the survey more convenient for the students who were often fitting the survey into a very tight schedule. However, the online version was unsuccessful for getting students to respond (only half of students responded). Therefore, for the final two time points, both paper and online versions of the questionnaire were offered. A small number of students continued to respond via the online version. Students were given a small financial incentive to participate.

Figure 1.

Date collection flowchart. The number of students who completed surveys at each time point is indicated. The survey format at each time point is also described.

Student participants signed an informed consent for both the questionnaires and focus group portion of the study. For the questionnaire component of the study the researchers met with students who were interested at the beginning of the first semester junior year (Time 1). At this meeting the researchers explained the study and handed each student a packet containing both the informed consent and questionnaires in a sealed envelope which was coded with a study identification number. Time was allowed to answer any questions. Students were provided a private room to review the informed consent and complete the questionnaires. Students returned both the signed informed consent and completed questionnaires during this meeting time. Students completed the questionnaires within 20 minutes. After the last survey had been administered and data was analyzed, two focus groups were conducted to explore the ways students felt their education may have influenced attitude and preferences changes that were found in the first phase. During the last survey, students were asked to indicate whether they would be willing to participate in a focus group. Interested students were then contacted for availability to attend one of two focus groups. The convenience sample of the first 10 students who indicated they were available during the scheduled times were solicited for participation. Four students participated in one group and six students in the other. Researchers met with each group, explained the study, and obtained informed consent prior to conducting the focus group.

Two members of the research team (BK, TR) facilitated both focus groups. A discussion guide was created based on the results from the Kogan scale and the preference questionnaire. Each focus group lasted 60 minutes and was held in a private office area in the school of nursing. Student participants for the focus groups were female.

Statistical Analysis

To describe change in attitudes over time, a Latent growth curve model (LGCM) was constructed using Mplus 5.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007). LGCM is a procedure that would allow exploration of attitude trajectories, or patterns in attitude scores across students (inter-individually) over time. LGCM is appropriate for exploring how change over time may be different for individuals. For example, modeling the students’ trajectories could show that a groups of students start out with high attitude scores that decline over time, one group whose attitudes scores generally stay the same across time, and another group with attitude scores that start low and get higher over time. The LGCM has a number of extensions available that allows researchers to add covariates and other variables to the model to determine what influences the trajectories. The model was adjusted for the unequal intervals between data collection periods. Missing data were treated as missing completely at random and handled by the maximum likelihood estimation procedures in Mplus.

Paired Wilcoxon rank sum tests were conducted using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., 2008)to determine change in age group and work setting preferences over time. Wilcoxon rank sum tests are appropriate to determine whether the means of paired observations that are not normally distributed differ significantly. Each age group or work setting was treated as a family of contrasts and a p-value was assigned to each family using a Bonferroni correction.

Qualitative analysis

During focus groups, notes were taken regarding the topics that students discussed. Two members of the research team (BK, TR) took notes during the session to enhance capacity to capture as much detail as possible about the discussions. No audio recordings were made of the sessions. Notes were then subjected to thematic analysis according to the six step process proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Two members of the research team (BK, TR) analyzed the data. Immediately following the focus group sessions notes taken by both research team members were reviewed and discussed, jotting down initial ideas about student responses. This was followed by a coding process where both researchers assigned codes to the data. Once codes were assigned the researchers discussed the codes and reviewed the data to determine if codes appeared systematically across responses until agreement was achieved with code assignment. Together the researchers collated codes into themes, reviewed for their fit to the data, and named the themes.

Results

Participants were predominantly female (85%), Caucasian (85%), and 18-25 years old (71%). See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Demographic information

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18-25 | 57 (71.3) |

| 26-33 | 15 (18.8) |

| 34-41 | 5 (6.3) |

| 42-49 | 0 (0.0) |

| Over 50 | 1 (1.3) |

| Missing | 2 (2.5) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 68 (85.0) |

| African American | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2.5) |

| Asian | 3 (3.8) |

| Other | 2 (2.5) |

| Missing | 5 (6.3) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 68 (85.0) |

| Male | 12 (15.0) |

Survey results

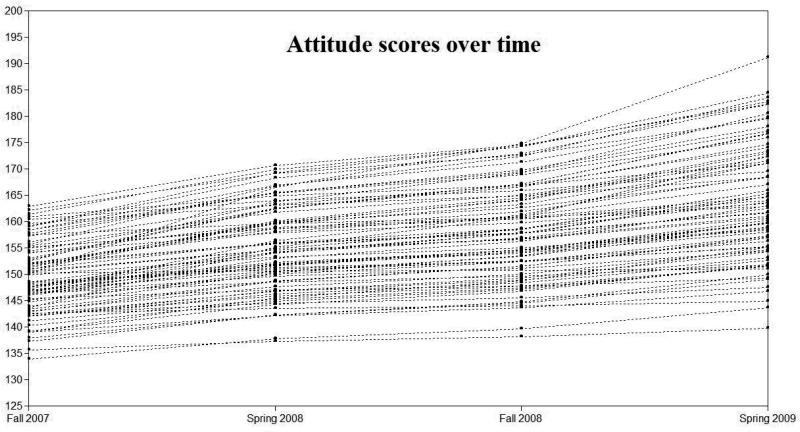

The mean Kogan attitude score was highly positive at Time 1 (149.13) and demonstrated an upward trend over time (Figure 2). The model intercept and slope were statistically significant. In other words, the average attitude score (149.13) is significantly different than zero at the beginning (intercept) of data collection and the rate at which the attitude score increases (slope) is significantly positive (Table 2). This means that students, on average, began their nursing program with already highly positive attitudes toward older adults. Nevertheless, students continued to become even more positive toward older adults over the course of their nursing program.

Figure 2.

Student attitude trajectories from latent growth curve model.

Table 2.

Results of latent growth curve model of attitude

| Variable | Coefficients (SE) |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 149.159* (1.124) |

| Slope | 0.718* (0.103) |

| Intercept variance | 62.736* (13.758) |

| Slope variance | 0.244* (0.089) |

| Chi-square | 11.435* |

| CFI | 0.881 |

| TLI | 0.858 |

| RMSEA | 0.127 (90% CI 0.02, 0.225) |

| AIC | 1965.302 |

| BIC | 1986.740 |

Note.

Significant values at p<0.05.

There was also significant variation in the intercept and slope. In other words, there are differences across students in where their attitudes start and the rate at which they increase. This means that students had significantly different attitudes from each other when they began the program. While scores were generally quite high on average, there were students who started the program with significantly more positive attitudes than others. Furthermore, while student attitudes, on average, became more positive over the course of the nursing program, not all students’ attitudes improved by the same amount.

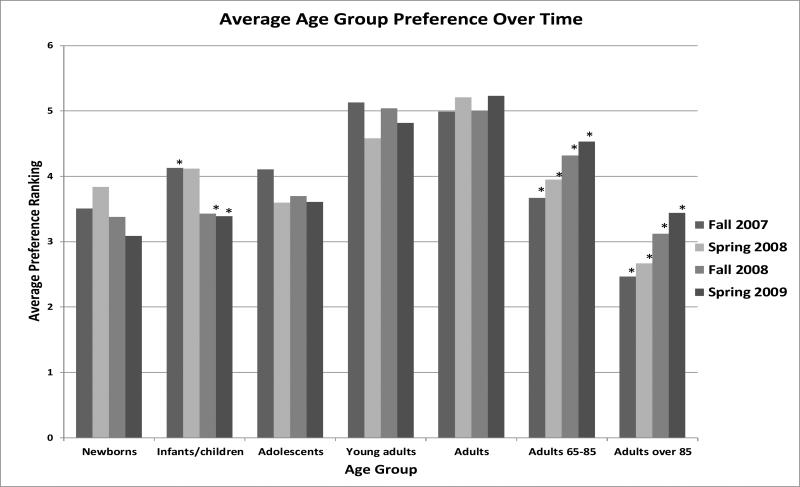

Paired Wilcoxon rank sum tests indicate that there were some changes in age group and work setting preferences over time1. Students appear to generally prefer to work with young adults and adults the most (Figure 3). While preference to work with these two groups remained the highest over time, there were changes in preferences for some age groups. There was a reduction in preference to work with infants and children and an increase in preference to work with older adults over time. Furthermore, by Time 4, working with older adults aged 65-85 was the third most preferred population to work with by students.

Figure 3.

Average preference for age group over time. Ranks were reverse coded so that a high rank indicates a higher preference for age group. * denote ranks that are significantly different from each other at a p value ≤.008. Specifically the following contrasts were significant; 1) Infants/children Fall 2007 with Fall 2008, 2) Infants/children Fall 2007 with Spring 2009, 3) Adults 65-85 Fall 2007 with Fall 2008, 4) Adults 65-85 Fall 2007 with Spring 2009, 5) Adults 65-85 Spring 2008 with Spring 2009, 6) Adults over 85 Fall 2007 with Fall 2008, 7) Adults over 85 Fall 2007 with Spring 2009, and 8) Adults over 85 Spring 2008 with Spring 2009.

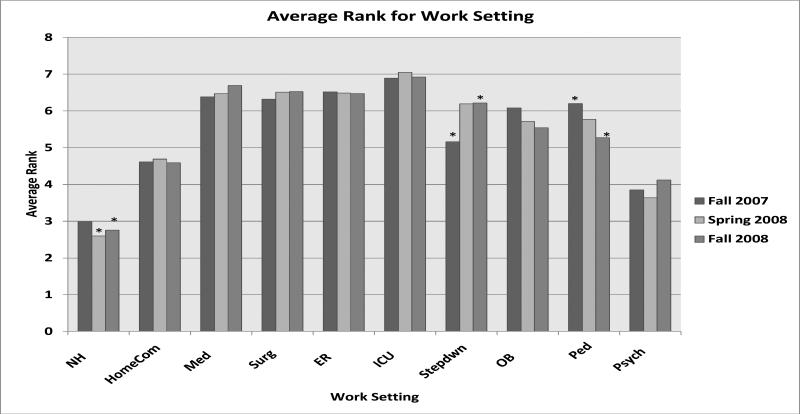

There was little change over time in work setting preferences (Figure 4). Students highly preferred working in acute care settings, particularly in intensive care units, and there was little change over time in this. Preference for working in pediatric units decreased over time. Furthermore, while there was a negligible increase in working in nursing home settings, these settings were consistently the least preferred places to work over time.

Figure 4.

Average preference rank for work setting. Ranks were reversed coded so that a high rank indicates a higher preference for work setting. * denote ranks that are significantly different from one another at a p value ≤.017. Specifically the following contrasts were significant; 1) Nursing home Spring 2008 with Fall 2008, 2) Stepdown Fall 2007 with Fall 2008, 3) Pediatrics Fall 2007 with Fall 2008.

Focus group results

To better understand the results of the attitude and preference surveys, two issues were explored in the focus groups; what aspects of nursing education students felt might have contributed to the attitude and preference changes over the course of the program and why students felt that working in nursing homes was preferred least. When responding to the first topic, students described two primary ways in which education contributed to attitude and preference changes; by a) dispelling myths and b) meeting or challenging expectations. When responding to the second topic, students described generally that their education left them feeling unprepared to work in nursing homes.

Dispelling myths

Students describe having preconceived notions of what caring for older adults would be like. Students believed that older adult nursing was “slow” and not very complicated (noted as undesirable qualities in a job). However, students indicated that the geronotological nursing course they took at the beginning of their senior year was important for changing their ideas, or dispelling myths, of what it is like to care for older adults. The students described the course as instrumental in enhancing their understanding that caring for older adults is extremely complex, particularly given issues with comorbidities and polypharmacy. They reported that this changed their minds about the desirability of working with the older adult population.

Meeting or challenging expectations

Students described exposure in a clinical area as something that influenced their preference for future work site or patient population. Generally, exposure to patient populations or work environment through a clinical rotation could change preference by either confirming or challenging expectations students had for what the experience would be like.

Students described knowing when they started the nursing program where and with whom they wanted to work. Only in situations where their experiences in these clinical sites did not meet their expectations (in either positive or negative ways), did their preferences change. For example, one student indicated she was interested in obstetrics and pursuing a future degree as a midwife when she started the program. However, after the student had a clinical at a Veteran's Hospital where she spent most of her time caring for older adults, she changed her preference. She found the experience interesting and very enjoyable, which was unlike what she was expecting it to be. She now indicated she would pursue working with older adults after graduation.

Students gave several more examples of how they often found clinical rotations where they primarily cared for older adults, surprisingly interesting and complex. Students were considering taking a job in these settings after graduation despite having different intentions at the beginning of their program. On the other hand, students also gave examples of how the setting they initially intended to work in after graduation did not live up to expectations. These students were seeking to avoid employment in these kinds of settings.

Feeling unprepared

In relation to the nursing home setting, students mentioned several reasons for not choosing work in nursing homes including; poor care quality, lack of resources to provide quality care, and a slow paced environment. However, beyond these reasons, students felt very strongly that the nursing home environment was complex and overwhelming for new graduates and they were unprepared to work in such a setting. Students indicted that RN's in nursing homes settings needed to function independently and as managers. These attributes were ones not emphasized in their school of nursing and were intimidating to students who felt they were not ready to take on this role right after graduation. Students reported that had they had the opportunity to have a clinical in the nursing home setting, they may have been more comfortable considering the setting as a possible place of employment after graduation.

Discussion

The longitudinal nature of our study revealed a positive trend in attitudes toward older adults over the entire nursing program, not just immediately after the gerontological nursing course. This may indicate that there is something occurring during the nursing program in addition to, or instead of the geronotological course, that is changing attitudes. Findings from the focus group indicate that the gerontological course seemed to have a positive influence on students’ views of older adults. Students felt the course helped dispel myths they had about caring for older adults and the course made them appreciate how complex caring for older adults can be. Therefore, the gerontological course has inherent value for improving the views students have about caring for older adults, but it may not be the only force driving attitude change.

The significant variance, and the somewhat poor fit of the model, found in the LGCM in students’ initial attitude scores as well as their growth trajectories indicates that student attitudes could be explained by other variables. However, due to a lack of prior information regarding the educational factors that may influence attitude trajectory, covariates and other variables were not added to this model. The goal of this study was to establish that there was significant variance over time in attitudes and explore – through qualitative inquiry – the possible educational factors that may influence these trajectories. A future study should be conducted in which covariates and explanatory variables are added to the model; specifically, gerontological courses and clinical placements should be added as time-variant predictors. Despite the limitation of the fit, a fair amount of variance was explained by the model and one can draw some general conclusions about the nature of changing attitude scores over time. The results raise questions about whether attitudinal improvement may be occurring regardless of exposure to gerontological content. If attitudes are changing despite exposure to gerontological content, this may offer a possible explanation for the results of studies where changes in attitudes have occurred despite the particular way gerontological nursing content was delivered or timed. Attitude changes in these studies may have been found whether students were exposed to gerontological content or not.

By dividing work preferences into preference for age group and preference for work setting, interesting trends were discovered. Our study found that it is not that students do not want to work with older adults; students do not want to work in nursing homes. There was clear and significant change over time in students’ preferences to work with older adults over the course of the nursing curriculum with students reporting a higher preference for working with older adults at each time point.

Focus group data can help explain why this change in preference to work with older adults may have occurred. Students indicated that having exposure to older adults in their clinical rotations in acute settings impacted their preference. Students reported enjoying working with older adults and found this population as an appealing group of patients to work with in the future. Further research on the affect of student exposure to older adults in a multitude of clinical settings on preference to work with older adults upon graduation should be pursued.

As found in other studies, our study also found that students ranked working in nursing homes lowest throughout the course of the study. This preference may be partly related to the socialization process of the nursing program. The nursing curriculum at the study site places a strong emphasis on delivery of care in hospital settings. This emphasis is mirrored in the student's work setting preferences. Students predominantly, and with nearly equal preference, indicated their interests were in working in acute care hospital settings and these interests stayed relatively stable over time. Students in the focus groups stated that they were not offered an opportunity to have a clinical in a nursing home. These students indicated that a nursing home clinical might have changed their preference about work setting Additionally, students stated that they were led to believe that nursing home settings were not a place for RNs but rather LPNs and that RNs should work in acute care settings. A lack of preparation during the program for a role in nursing homes may also contribute to the lack of interest in the setting. Students provided new insights during the focus groups as to why students may be ranking long term care settings lowest. Students saw long term care as too challenging for them to handle as a new graduate. Students indicated that being the sole person to make decisions about care of the older adults and needing to supervise others as intimidating. They felt they did not have the training to be managers or supervisors or work independently as nursing homes nurses.

Several strategies have been developed to target nursing student socialization and influence student attitudes and preference to work with older adults, particularly in long term care settings. The Teaching Nursing Home Projects (TNHs) sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institutes of Aging created affiliations between nursing homes and university schools of nursing. Results from THN studies demonstrated that such affiliations not only improved nursing students’ attitudes towards older adults but also strengthened geriatric curriculum (Mezey et al., 2008; Mezey et al., 1988). However, the impact of TNH on student preference for employment in nursing home settings was not explored.

The University of Minnesota, School of Nursing developed a conceptual model to guide clinical teaching in nursing home settings (Mueller et al., 2011). The model is based on four factors that are essential for developing quality clinical experiences for students in nursing home settings. These factors consist of 1) select a nursing home that provides quality resident care (use of evidenced-based care practices and resident-directed care, role of RN distinguished from licensed practical nurses and nursing assistants) and has sufficient resources (RN staffing higher than national average); 2) ensure that nursing faculty who teach in the nursing home setting receive a solid orientation to the environment, staff roles, care practices and current trends in nursing home care; 3) develop a strong partnership with the nursing home setting (shared understanding of each other's goals and needs, nursing home staff engaged in teaching students and serve as role models); and 4)use of creative and innovative teaching strategies (students experience a variety of RN roles in a nursing home setting, manage care for a group of residents, and are responsible for delegation and supervision of resident care). The premise for the Minnesota model is that creating and implementing an exemplary clinical experience will provide students with a positive image of nursing homes and may influence their work preference for nursing home settings.

Each of these programs demonstrates high potential for changing student attitudes and preferences. However, as identified by the students in the current study, programs that focus on both theoretical gerontological nursing content and clinical rotations may likely have the most success in changing students’ attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults. Gerontological Nurse Extern (GNE) programs combine clinical opportunities with focused education. The Long Term Care Clinical Scholars Program for example, places nursing students in temporary employment in nursing home settings to prompt student nurse interest in working in nursing home settings. Nursing students work under the supervision of RN preceptors performing procedures and activities identified in the program guidelines. In addition to this intensive clinical opportunity, the students attend focused gerontological and long term care specific education as didactic workshops over the course of the summer externship. Students receive supplemental education in these workshops that address limitations in their nursing programs such as supervisory and management skills. Benefits of GNE programs include, promoting students’ interest in employment in nursing home settings, dispersing negative images of nursing homes, reinforcing students’ prior education through clinical practice and easing transition of students to staff nurse roles (Bowers, 2012).

Further research should be pursued to examine how innovative strategies, in addition to a gerontological nursing course, incorporated into nursing curricula may affect nursing student socialization, attitudes toward older adults and work preferences for nursing home settings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The study was conducted in a single institution and may not be representative of nursing schools in general. This particular school of nursing does not require all nursing students to complete a clinical rotation in a nursing home. Selection bias may also further limit generalizability as students volunteered to complete the surveys. In addition, students who elected to participate in our study may have been made more aware of their attitudes toward older adults as the study progressed also potentially biasing the results. There may have also been a retesting phenomenon. While attitude and preference surveys were delivered months apart, there is still some possibility that students were “learning” how to respond to the surveys making their scores higher over time. Finally, there may have been some social desirability bias in the ways students responded to the questionnaires.

As described in the methods section, the format and survey questions changed slightly over time and may bias results. The change in format from paper to online may have biased results, particularly given that only about half of the sample responded to time 2 measures when the questionnaire was given only online. Students stated in focus groups that there really was not any incentive to complete the survey online (although they still received the same monetary reimbursement) and it was easy to just delete it from their emails without completing it.

Additionally, the question regarding work preferences at Time 4, which was significantly altered in content from the previous three time points, was not analyzed. It is possible that if preferences from time 4 could have been included in the data analysis that the results would have been different. However, given the stability of these work setting preferences during the first three time points, it seems unlikely that the time 4 preferences would have been much different or changed the outcome.

Students also gave important feedback during the study about the attitude questionnaire. Students felt that the Kogan was dated, and they were unfamiliar with some of the phrases used on the form (eg. Ill at ease) and that their attitudes may not have been adequately captured using the Kogan. This could be a serious limitation to our conclusions and future researchers should consider alternative measures for assessing attitudes towards older adults.

Conclusions

Schools of nursing are presented with a unique challenge and opportunity of preparing nurses to provide high quality care to older adults across a variety of care settings. This is critical challenge as our population of older adults is expected to double over the next 20 years (Institute of Medicine, 2008). Results from this study suggest that schools of nursing may be able to play a role in influencing how students perceive and prefer to work with older adults. In particular, gerontological nursing courses are important to dispel myths about caring for older adults and clinical experiences caring for older adults during semester placements may be an important way students could be encouraged to choose working in settings where older adults primarily are. Presenting numerous opportunities to have well-planned, supported, and positive clinical rotations in nursing home settings is important to encourage students to see work in this setting as a viable option. Furthermore, interest in caring for older adults in nursing homes may require attention to preparing students not only in clinical skills and tasks, but leadership and supervisory roles as well.

Acknowledgments

This study did not receive granting support from any outside funding mechanism. University funding support was provided through the Helen Denne Schulte Professorship for subject incentives. Barbara King's training through the conduct of this study was supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation- Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholarship program. Tonya Roberts’ training during the conduct of this study was supported by award number T32NR007102 from NINR and the John A. Hartford Foundation-Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholarship program. The content of this manuscript is solely that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statements

Barbara King, Tonya Roberts, and Barbara Bowers have no financial conflicts of interest.

Declare of assistance for study design

The authors acknowledged the generous assistance from Dr. Jeffrey Henriques with on-line survey development and management.

A growing aging population will require nurses who prefer to work with older adults. Schools of nursing have used several strategies to improve students’ attitudes and preference to work with older adults. However, research on these strategies is inconsistent, with some programs improving students’ attitudes while others having no effect. More recent studies have found that although attitudes have improved, working with older adults is generally least preferred. The purpose of this longitudinal mixed methods study was to describe and explain student nurse attitudes and preference change over time. Eighty undergraduate nursing students were surveyed over 2 years. Students’ attitudes and preference for working with older adults improved over time. However, their preference to work in nursing homes was consistently ranked last. In focus groups students reported that the gerontological course dispelled myths about caring for older adults and clinical placement played a major role in influencing student work preference.

Time 4 work setting data could not be analyzed because of an error in the questionnaire wherein the question asked was substantively different than at the other three time points. At time 4 participants were asked to rank only the places they had applied for a job, rather than all settings.

Contributor Information

Barbara J. King, Advanced Special Fellow Geriatrics William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Administration Hospital 2500 Overlook Terrace Madison, WI 53792.

Tonya J. Roberts, John A. Hartford BAGNC Scholar University of Wisconsin – Madison, School of Nursing H6/292B CSC 600 Highland Ave. Madison, WI 53792.

Barbara J. Bowers, University of Wisconsin – Madison, School of Nursing H6/250 CSC 600 Highland Ave. Madison, WI 53792.

References

- Administration on Aging . Statistics. A profile of older Americans: 2002. Health, health care and disability. Washington D.C.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bednash G, Fagin C, Mezey M. Geriatric content in nursing programs: a wake-up call. Nursing Outlook. 2003;51(4):149–150. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(03)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais K, Mikolaj E, Jedlicka D, Strayer J, Stanek S. Innovative strategies for incorporating gerontology into BSN curricula. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2006;22(2):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B. Wisconsin Long Term Care Clinical Scholars Program. Wisconsin Department of Health Services; 2012. (Contract #FCJ23059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe VJ. The effects of gerontology nursing teaching methods on nursing student knowledge, attitudes, and desire to work with older adult clients. PhD, Walden University; Minneapolis: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rue M. Preventing ageism in nursing students: an action theory approach. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;20(4):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg I, Winblad B, Ekman S. Influencing aspects in nursing education on Swedish nursing students’ choices of first work area as graduated nurses. The Journal of nursing education. 2000;39(5):211. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20000501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill E, Baker M. The effects of a well older adult clinical experience on students’ knowledge and attitudes. The Journal of nursing education. 1986;25(4):145. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19860401-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter LM. Students’ attitudes toward geriatric nursing. Nursing Outlook. 1971;19(7):466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight BK, Christ MA, Dias JK. Does nursing education promote ageism? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;20(2):382–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20020382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock D, Helfers MJ, Cowen K, Letvak S, Barba BE, Herrick C, et al. Integration of gerontology content in nongeriatric undergraduate nursing courses. Geriatric Nursing. 2006;27(2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B. When I grow up I want to be a...? Where undergraduate student nurses want to work after graduation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(2):499–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happell B. Nursing home employment for nursing students: valuable experience or a harsh deterrent? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;39(6):529–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart LK, Freel MI, Crowell CM. Changing attitudes toward the aged and interest in caring for the aged. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1976;2(4):10–16. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19760701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J, Xiao L, Siegloff L, Kelton M, Paterson J. ‘Older people have lived their lives’: First year nursing students’ attitudes towards older people. Contemporary Nurse. 2008;30(1):32–45. doi: 10.5172/conu.673.30.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd A, Dahlke S, Fehr C, Jung P, Hunter A. Attitudes toward aging: implications for a caring profession. The Journal of nursing education. 2009;48(7):374. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090615-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Retooling for an Aging America. Building the Health Care Workforce. National Academies Press; Washington D.C.: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . The Future of Nursing. Leading Change, Advancing Health. National Academies Press; Washington D.C.: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen DA, Morse WA. Positively Influencing Student Nurse Attitudes Toward Caring for Elders. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education. 2004;25(2):1–14. doi: 10.1300/J021v25n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser JS, Minnigerode FA. Increasing nursing students’ interest in working with aged patients. Nursing Research. 1975;24(1):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloster T, Høie M, Skår R. Nursing students’ career preferences: a Norwegian study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59(2):155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan N. Attitudes toward old people: The development of a scale and an examination of correlates. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1961;62(1):44–54. doi: 10.1037/h0048053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren ME, Hertz J, Munroe D, Rossetti J, Robertson J, Plonczynski D, et al. Assessing students’ learning needs and attitudes: considerations for gerontology curriculum planning. Gerontology and Geriatrics Education. 2008;28(4):39–56. doi: 10.1080/02701960801963029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, Clark E, Lu S. Bachelor of Nursing students career choices: a three-year longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today. 2010;30(1):31. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey M, Boltz M, Esterson J, Mitty E. Evolving models of Geriatric Nursing care. Geriatric nursing (New York, NY) 2005;26(1):11. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey MD, Mitty EL, Burger S. Rethinking teaching nursing homes: Potential for improving long-term care. The Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):8–15. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey MD, Lynaugh JE, Cartier MM. The teaching nursing home program, 1982-87: A report card. Nursing Outlook. 1988;36:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle W. Nursing students’ perceptions of older people: Continuing society's myths. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;20(4):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller C, Goering M, Talley K, Zaccagnini M. Taking on the challenge of clinical treaching in nursing homes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011;37(4):32–38. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110106-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. Fifth ed. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plonczynski DJ, Ehrlich-Jones L, Robertson JF, Rossetti J, Munroe DJ, Koren ME, et al. Ensuring a knowledgeable and committed gerontological nursing workforce. Nurse Education Today. 2007;27(2):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffler SJ. Do clinical experiences affect nursing students’ attitudes toward the elderly? The Journal of nursing education. 1995;34(7):312–316. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19951001-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto Y, Rose C. Identifying interest in gerontology. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1987;13(2):8. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19870201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snape J. Nurses’ attitudes to care of the elderly. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1986;11(5):569–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1986.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS Base 16.0 for Windows User Guide. SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Treharne G. Attitudes towards the care of elderly people: are they getting better? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1990;15(7):777–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Anderson MC, Day R. Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Aging: Comparison of Context-Based Learning and a Traditional Program. Journal of Nursing Education. 2007;46(3):115–120. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20070301-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]