Abstract

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI indirectly images exchangeable solute protons resonating at frequencies different than bulk water. These solute protons are selectively saturated using low bandwidth RF irradiation and saturation is transferred to bulk water protons via chemical exchange, resulting in an attenuation of the measured water proton signal. CEST MRI is an advanced MRI technique with wide application potential due to the ability to examine complex molecular contributions. CEST MRI at high field (7 Tesla) will improve the overall results due to increase in signal, T1 relaxation time, and chemical shift dispersion. Increased field strength translates to enhanced quantification of the metabolite of interest, allowing more fundamental studies on underlying pathophysiology. CEST contrast is affected by several tissue properties, such as the concentrations of exchange partners and their rate of proton exchange, whose effects have been examined and explored in this review. We have highlighted the background of CEST MRI, typical implementation strategy, and complications at 7T.

Keywords: CEST, 7T, MRI

Introduction

Image contrast in standard clinical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is based on the concentration of protons associated with water and the environment in which they exist. Conventional MRI acquisition schemes, such as T2-and T1-weighted (with and without Gadolinium contrast agents), reveal anatomical information and reflect tissue integrity via the presence or paucity of inflammation, but suffer from the ability to detect the underlying microstructural tissue composition. Alternatively, a recently described MRI contrast mechanism, chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST1,2), is sensitive to solute/water proton interactions of exchangeable protons, which resonate at specific spectral frequencies. Based on the chemical exchange between these solute protons and those of water, CEST MRI can detect low-concentration metabolites through their intimate communication with surrounding water (thus affecting the observed water signal) without the use of exogenous contrast agents. Recently, a few exceptional reviews have explored the topic of CEST MRI3-5 and to avoid replication, we focus on the application and limitations of CEST MRI on humans at 7 Tesla (7T).

CEST MRI Theory

The goal of CEST MRI is to indirectly detect exchangeable solute protons that resonate at frequencies different (Δω) from those protons associated with bulk water. These solute protons are selectively saturated using narrow bandwidth RF irradiation and this saturation is transferred to the bulk water protons via chemical exchange, resulting in an attenuation of the measured water proton signal6. If these nuclear spins are of sufficient concentration and in slow/intermediate exchange (i.e. their exchange rate is less than or equal to the irradiation offset frequency) then substantial enhancement of these proton’s visibility through the significant transfer of saturation will occur thereby allowing low concentrations of solute to be imaged indirectly.

The relative saturation is typically expressed as a signal change relative to an acquisition in the absence of irradiation (S0), similar to how the magnetization transfer (MT) ratio is characterized. The signal due to irradiation at a specific frequency, S(+Δω), and normalized by the signal in the absence of saturation, S0, is termed a saturation z-spectrum7, and in the case of CEST, is termed the CEST z-spectrum. For CEST imaging, this z-spectrum is characterized by 3 components: 1) a symmetric (with respect to the water frequency, or Δω = 0) direct saturation (DS) effect8, 2) a slightly asymmetric magnetization transfer effect9, 3) an asymmetric Nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)10, and 4) an asymmetric CEST effect resulting from chemical exchange. In principle, 1) cannot be avoided, but in order to accurately detect the CEST effect, minimization of MT effects is paramount11,12. While we will focus our attention on the characterizing the CEST effect at high field, we recognize that direct saturation, NOE, and MT effects can hinder a quantitative assessment of CEST effect. This has been recently addressed by Desmond and Stanisz13.

If a sufficient concentration of mobile exchanging species exists, an asymmetry in the CEST z-spectrum due to chemical exchange is observed. One method typically used to characterize these effects on the z-spectrum calculates the asymmetry as such:

| (1) |

The magnitude of the CESTasym effect depends on a number of physiological (concentration, exchange rate, and spectral position of the protons of interest, along with the relaxation times of both the water and labile protons), and experimental (transmit field (B1) magnitude, duration (tsat), and homogeneity, and static magnetic field inhomogeneity) parameters. Reproducibility of this measurement could be hindered by the presence of NOE, which appears in the reference region for the typical metabolites of interest. Despite this, reproducibility of the CESTasym caused by amide protons, termed amide proton transfer (APT), has been demonstrated in regions of interest in the brain14.

Using an exchange model consisting of two pools, a small solute pool and large bulk water pool, a solution for the proton chemical exchange, the proton transfer ratio (PTR), can be derived in the absence of direct water saturation and MT effects 5,15,16:

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

In other words, the measured CEST effect increases with the fractional concentration, xs, (indicated by square brackets), saturation efficiency, α, the exchange rate, ksw, and the longitudinal relaxation time of water, T1w17,18. This allows specific design of agents and MRI pulse sequences to optimize the CEST contrast based on the metabolite of interest.

Complications of CEST MRI

According to Equations (2) and (3), the contrast derived from CEST MRI is affected by several important, physiological tissue properties such as the concentrations of the exchange partners as well as the rate of proton exchange making CEST MRI an invaluable tool to quantify tissue characteristics on a molecular level. However, this sensitivity can be hampered by unwanted influences from other sources of contrast, particularly DS effects and the underlying MT asymmetry. DS in resonances close to that of the water frequency becomes a large contributor and is largely influenced by the tissue T219. Because the resonances of interest can be obscured by the DS effect, this may influence the sensitivity to detect protons with a resonance frequency in this range. Additionally, the resonances near water are often in a fast exchange regime making their affect on the water signal difficult to detect. In order to characterize the CEST effects of these protons, the DS effect can be minimized using either specifically designed acquisition schemes or asymmetry analysis, as explained by Equation (1), since the DS effect is largely symmetric8. This asymmetry analysis is based on the assumption that all non-CEST contributions are symmetric about the water resonance. While true for DS, the underlying MT effects have been shown to be asymmetric9. Specifically, it has been shown that a negative asymmetry exists in the MT spectrum, which depends strongly on the RF power and bandwidth used for saturation9. In the complex environment in vivo, the presence of this conventional MT asymmetry cannot simply be ignored9,20. A method for separating this asymmetry from the macromolecular pool (MT) from that of the exchanging protons (CEST) which takes advantage of the distinct T2 values utilizing phase cycling has been proposed by Narvainen, et al.21. Alternatively, attention has been paid to: 1) reduction of the saturation power and duration, 2) alternative quantification strategies11,22, and 3) a combination. The origin of this MT asymmetry could be explained by the asymmetry of the solid pool macromolecular MT effect9 or intra/intermolecular Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) of aliphatic protons of mobile macromolecules and metabolites2,23,24.

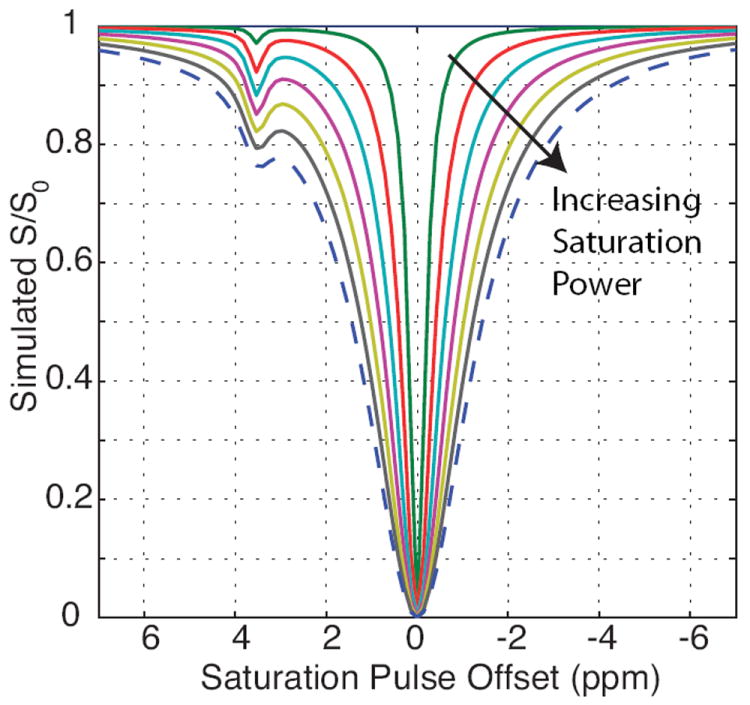

As previously mentioned, the contrast derived from CEST MRI is largely dependent on the pulse sequence design25,26. This dependence of CEST contrast on the RF pulse parameters has been explored using simulations27,28, in vitro29 and in vivo30 with parameters such as RF saturation duration (tsat) as well as the total power transmitted both affecting CEST contrast. Figure 1 displays simulation results of varying the saturation power, B1, and how it can alter the resulting z-spectra. Based on the MRI parameters implemented, the relative magnitude of the CEST effect can vary significantly, thus care should be taken to minimize competing phenomena when characterizing the CEST affect and subsequent comparisons among studies.

Figure 1.

Simulated CEST effect demonstrating the effects of changes in saturation power (B1) for a sample containing bulk water and amide protons in slow/intermediate exchange.

Significance of Increased B0

It has been shown that increased static magnetic field, B0, can have a substantial impact on imaging methods. However, transitioning to higher field strengths pays greater dividends for CEST imaging. First, typical CEST experiments, when transitioned to higher field strength result in an increase in the chemical dispersion as well as an increase in signal to noise ratio (SNR). For the latter, theoretically, the water SNR increases linearly with field strength, which can be used for higher resolution, better anatomical coverage, or a decreased imaging time when compared to lower field. For the former, the chemical dispersion (i.e. the off-resonance frequency of exchangeable protons is further from the water resonance at higher field than at lower field) is increased at 7T, resulting in the resonance of the metabolites of interest occurring farther from water compared to 3T. To observe the CEST effect, the exchange rate must be less than or equal to the spectral resonant frequency (Δω≥ kex). At higher field strengths, Δω increases and thus will influence the ability to observe exchange of protons with a faster exchange. Greater spectral dispersion of the resonances of interest permits better spectral selectivity of the RF irradiation by decreasing saturation pulse bandwidth demands (i.e. larger bandwidth irradiation will have less of an effect at higher field), which can minimize DS effects.

In addition to the increase in spectral dispersion, longitudinal relaxation times, T1, also increase with B0. This increase in T1 will create a more favorable PTR (Eq. 2) for detection of the CEST effect. Also, since the irradiation relaxes with T1, the longer T1 at higher field strengths allows for a longer time in which exchange can occur. Finally, it is important that protons of interest in CEST experiments must be in the slow to intermediate exchange regime. That is, the exchange rate must be less than or equal to the spectral resonant frequency (Δω≥ kex).

Since the resonances of interest can, in principle, be imaged with greater ease, the spectral dispersion and exchange rates more favorable, and an appreciable increase in the SNR afforded at 7T, translation of the CEST technique to 7T allows for enhanced quantification of the tissue mobile protons16,31,32, characterization of tissue type or pathological impact, and allows for more fundamental studies about exchange than have been performed at lower field.

Materials and Methods

Acquisition Techniques of CEST MRI

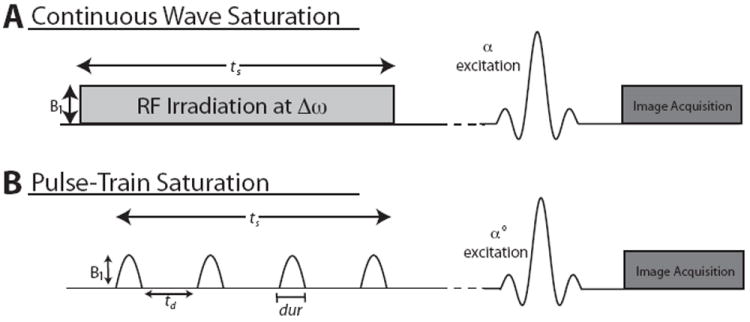

CEST data is acquired by applying a low-bandwidth irradiation to achieve saturation prior to an imaging sequence, as seen in Figure 2. This saturation can be achieved using a low bandwidth continuous wave (CW) RF pulse prior to the imaging sequence (Figure 2A). This pulse must be sufficiently long in order to reach steady state, increasing demands on the system hardware as well as the specific absorption rate (SAR) for human imaging studies. Saturation using a series of pulses (pulse-train) (Figure 2B) is an alternative option to decrease RF amplifier demands, but typically requires advanced pulse sequence design. Acquisition of CEST data involves sweeping this frequency-selective saturation pulse through a range of offsets and evaluating the effects on the water proton signal intensity. The saturation is followed with excitation and image readout, which must be rapid and distortion-free with a short dynamic scan time to achieve a clinically applicable exam.

Figure 2.

Pulse sequence diagrams for the continuous wave and pulse-train saturation methods to acquire CEST MRI data. B1 represents the pulse amplitude, tsat is the saturation time, td is the delay between pulses, and dur is the duration of each constituent pulse of the pulse-train saturation.

Alternatives to full z-spectrum acquisition have been proposed in order to decrease imaging time as well as circumvent contributions from DS and conventional MT asymmetry. One method to reduce acquisition time is to acquire high-resolution images following saturation at select offsets around the resonance of interest in combination with a lower resolution reference z-spectrum32,33. This technique was applied to examine characteristics of human brain tumors in vivo at 3T resulting in a clinically applicable imaging time (4.5 minutes) with ΔB0 compensation up to 130 Hz33. Migration of this technique to a 7T human scanner could be hindered by the increase in B0 inhomogeneity, which has been demonstrated to be up to 200 Hz14. Mougin et al.32 maintained a reasonable imaging time at 7T by acquiring only at the amide resonance and its reference (±3.5ppm) increasing sensitivity to B0 inhomogeneities present at this high field. Keyhole imaging, a technique typically used for dynamic contrast, has also been applied to decrease the acquisition time of CEST imaging by decreasing k-space sampling34.

Modified pulse sequences have also been used to accomplish decreased acquisition time and address the presence of unwanted contributions from the conventional MT asymmetry. Sun et al.35 unevenly segmented the RF irradiation into a long primary irradiation to achieve steady state followed by a repetitive short secondary irradiation to lock the CEST contrast. Multi-slice imaging was performed following these irradiations minimizing the total scan time. Scheidegger et al.11 addressed the unwanted contributions from conventional MT as well as direct water saturation using a novel saturation scheme. Alternating RF saturation was utilized at 3T to result in images that were insensitive to B0 inhomogeneity up to ΔB0 values of 200 Hz by applying saturation pulses alternating between Δω and −Δω with a total acquisition time under 14 minutes.

Quantification

Quantification of the asymmetry caused by the presence of exchangeable protons (CESTasym) can provide direct information regarding molecular exchange with estimation of relative metabolite concentrations and exchange rates using either a two-15,16,36,37 or three-32,38 compartment model based on the protons’ environment. Modified Bloch-McConnell39 equations can be used to describe the evolution of the different pools of protons; 1. freely diffusing water magnetization (free pool, Mf), 2. pool of protons within small proteins in chemical exchange with the free pool (exchanging pool, Me), and 3. protons associated with macromolecules via the hydration layer (bound pool, Mb). Under reasonable conditions, the three-pool model reduces to two-pools and the metabolite concentration and exchange rate can be extracted. Assuming complete saturation and limited back-exchange from saturated water to the metabolites, the concentration and exchange rate can be calculated using Equation 4,

| (4) |

where k is the exchange rate, R1w is the water spin-lattice relaxation rate, and tsat is the saturation time17,40.

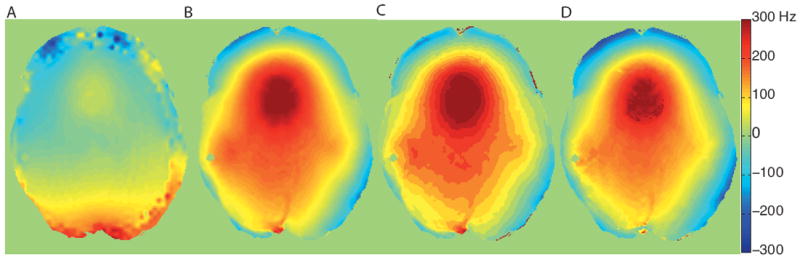

Image processing is crucial to accurate quantification of the CEST effect and should begin with a robust registration algorithm to avoid artifacts caused by subject motion. The saturation efficiency influences the asymmetry apparent in the CEST spectra and can be contaminated by an inhomogeneous B1 field. A B1 map41 can be acquired and used for adjustment of the measured signal intensity but for typical endogenous CEST applications, complete saturation is typically achieved in the applicable B1 range (1-3 μT) with sufficient saturation times. Furthermore, the saturation efficiency, α, can be calculated based on Eq. 2 using the estimated exchange rate and proton concentration and the measured T1. A practical drawback in CEST imaging is the observed z-spectral asymmetry is exquisitely sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneities (ΔB0), which can erroneously shift the center of the z-spectra. This may cause the z-spectrum minimum (i.e. point of maximum saturation) to deviate from the water on-resonance reference frequency and is further exacerbated at higher fields such as 7T. A ΔB0 map can be calculated using the dual echo method42,43 and the ΔB0 can be applied as the shift-correcting-map to account for static field inhomogeneities. Another method to correctly center the CEST spectra is to fit to a higher-order polynomial and find the minimum, which is deemed to be the center frequency, and shift each voxel’s z-spectra accordingly44. However, the robustness of this technique relies on sampling the minimum of the z-spectra in sufficient detail. An additional method involving a separate acquisition with low saturation power, detecting the direct saturation of water, has been used to establish the magnitude of the frequency shift caused by field inhomogeneities and is termed water saturation shift referencing (WASSR)45. The resulting direct water saturation spectrum is largely symmetric and directly samples at a resolution comparable to CEST acquisitions. This information has been used at 7T to correct the center frequency of the subsequently obtained CEST acquisitions on a voxel-by-voxel basis14. Recently, an alternate method has been proposed using a Lorentzian lineshape to fit the acquired data and estimate the center frequency shift46. Example shift maps calculated using the ΔB0 map (A), higher-order polynomial fit (B), Lorentzian fit (C), and WASSR method (D) can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Shifting maps used to center z-spectra calculated using the A) ΔB0 map, B) higher-order polynomial fit, C) Lorentizan fit, and D) WASSR.

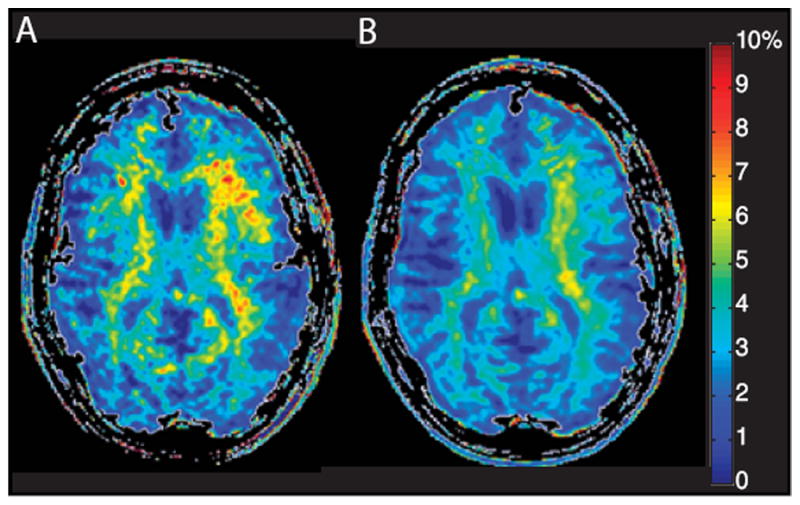

Quantification of the asymmetry caused by the presence of endogenous metabolites is typically accomplished using a point-to-point subtraction using Equation 1 where Δω is assigned as a discrete resonance of the metabolite of interest. Application of this method on a voxel-by-voxel basis results in an asymmetry map demonstrating the spatial distribution of exchanging species at that particular resonance. An integration method may be more appropriate based on the presence of line broadening due to the relative proton exchange rate and T2 effects as well as limitations on saturation pulse bandwidth. With this method, a range of frequencies are considered and the asymmetry spectrum is integrated voxel-by-voxel over this range, typically resulting in a smoother map of the metabolite’s spatial distribution, as seen in Figure 4. Furthermore, integration between a Lorentzian fit to the data and the acquired points around the amide resonance was recently used to examine the APT in human brain46.

Figure 4.

A) CESTasym maps calculated for the amide protons (APTasym) using A) point subtraction at ± 3.5 ppm and B) integration of asymmetry from -4 to -3 ppm.

Results, Discussion, and Conclusions

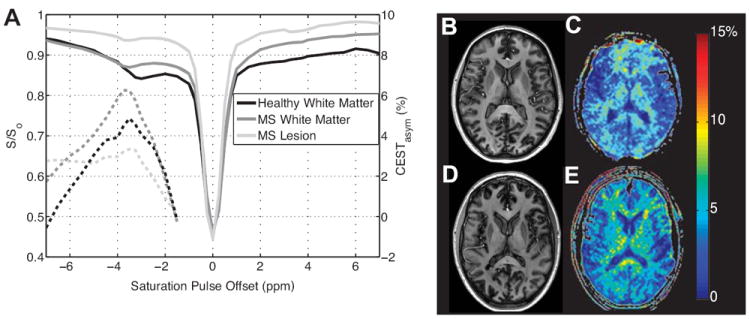

CEST MRI has been applied to examine various metabolites including glycogen23,36, amides6,17,46, and myo-inositol31 as well as tissue characteristics such as pH35,47,48. These studies have been performed in vivo on animals at both 7T and 9.4T and on humans at 3T. Recently, Mougin, et al. reported their experience with magnetization transfer in human brain at 7T32. Presenting methods of measuring the z-spectra as well as the MTRasym (CESTasym) of the amide protons, they quantified the presence of amide proton transfer asymmetry (APTasym = CESTasym(Δω = -3.5 ppm)). Results indicated a greater than 50% increase in the APTasym than found at 3T. They reported unwanted contributions from DS effects, causing elimination of frequencies < 300 Hz. Our group14 also presented quantification of APTasym at 7T on human brain acquiring a full z-spectrum for analysis. Both 7T studies reported interesting contrast between healthy neural tissue types based on the presence of amide protons not observed at lower fields and attributed this contrast to the increase in static magnetic field strength. Example z-spectra acquired at 7T with full spectral coverage can be found in Figure 5A. Regions of interest from white matter and gray matter result in unique z-spectra, solid lines, left y-axis, particularly at the amide resonance. The CESTasym is also shown (dashed lines, right y-axis) to demonstrate the distinct asymmetry caused by the presence of amide protons at 3.5 ppm downfield from water, detectable at 7T.

Figure 5.

Results of CEST MRI at 7T on healthy control and MS patient. A) Z-spectra arising from healthy white matter, MS patient white matter, and MS lesion, solid lines, left y-axis. CEST asymmetry is also shown, dashed lines, right y-axis. B) Anatomical image of healthy subject with the calculated APT asymmetry map shown in panel C. D) Anatomical image of MS patient with calculated APT asymmetry map found in panel E.

Applications of CEST MRI

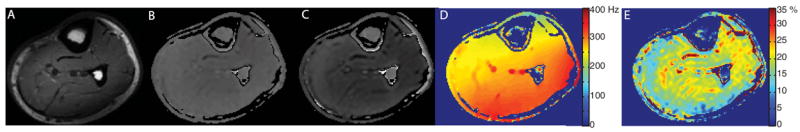

CEST examination of glycogen, glycoCEST, via selective saturation of the hydroxyl protons in the 0.5-to 1.5-ppm frequency range down field from water reveals information about tissue glycogen content36 and distribution complementary to 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). GlycoCEST can assess the systemic glucose homeostasis with pathological applications in abnormalities of glycogen metabolism such as inherited disorders and obesity. GlycoCEST has been applied to study muscle physiology at 7T and Figure 6 demonstrates how the spectral dispersion and increased SNR available at 7T can facilitate detection of the hydroxyl protons associated with glycogen. The spectral asymmetry map shown in Figure 6E demonstrates the spatial distribution of the exchanging hydroxyl protons associated with glycogen in the muscle of the lower leg. These hydroxyl and amino protons are also useful indicators of glycosaminoglycans, which are long un-branched carbohydrate chains playing a vital role in diarthrodial joints and intervertebral disks. The glycosaminoglycans, or GAGs, can be assessed using CEST (gagCEST23) based on the labile protons residing on three hydroxyl groups as well as the amide proton, with useful applications in central nervous system pathology such as mucopolysaccharidosis.

Figure 6.

Results from GlycoCEST of skeletal muscle at 7T. A) T1-weighted anatomical image, B) reference image for glycogen resonance (1.0 ppm), C) normalized image for glycogen resonance (-1.0 ppm), D) shift map calculated from polynomial fit with color scale in Hz, and E) asymmetry map for glycogen (1.0 ppm).

As previously mentioned, endogenous mobile proteins and peptides can be examined with focus on the amide protons, resonating 3.5 ppm downfield from water. CEST MRI of the amides, or amide proton transfer (APT) has been applied to pathologies such as tumors and ischemia due to stroke. APT imaging of tumors has provided information on the presence and grade of malignant brain tumors24,49 as well as breast tumors (Dula AN, et al. (2011) CEST MRI of the breast at 3T using amide proton transfer (APT). Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.) In addition, chemical exchange of the amide protons is often pH dependent resulting in calibration of the tissue microenvironment for pathologies such as ischemia28,50. Ischemic stroke-induced increases in T2 as well as decreases in pH and changes in protein/peptide content are detectible using APT MRI relating to the extent of ischemic infarct. APT CEST has also been applied to assess multiple sclerosis (MS) at 7T with the APT asymmetry varying based on the MS lesion type14,51. An increase in the APT asymmetry was found in the normal appearing white matter of MS patients, reflecting an increase in mobile proteins and peptides, while a decrease in APT asymmetry was found in necrotic lesions indicating a decrease in mobile proteins and peptides due to macrophage activity. The unique z-spectra arising from these different tissue types can found in Figure 5A. In addition to ROI analyses, it is also helpful to display the spatial distribution of the calculated CESTasym for a particular metabolite. Figure 5B shows the spatial distribution of the asymmetry caused by amides, APTasym map, for a healthy control as well as a MS patient with arrows indicating normal appearing white matter (white arrow) and MS lesion (yellow arrow).

CEST MRI has the potential to provide a comprehensive view of molecular aspects of neural tissue environment such as metabolite concentration, tissue pH, and metabolism. This endogenous contrast mechanism has the ability to be turned on and off based on imaging parameters. Although quantification is difficult to reproduce between labs due to the dependencies on saturation parameters, saturation efficiency, and image processing techniques, the limitations of higher field will fundamentally produce more uniform results. These limitations that are present at 7 T will constrain the saturation parameters, ultimately reducing the variation. The CEST effect will increase at higher fields due to the increased T1, allowing prolonged storage of saturation in the water pool. In addition, the frequency separation, or spectral dispersion, will affect the definition of slow/intermediate exchange (Δω ≫ k) and reduce unwanted contributions from DS. CEST MRI is an advanced MRI technique with wide application potential. The ability to examine complex molecular contributions relating to numerous neuropathologies provides complementary information to that available from existing MRI techniques. Migration to increased field strength results in enhanced quantification of the metabolites of interest, allowing for more fundamental studies on underlying pathophysiology.

The translation of CEST MRI into the clinic has the advantage of utilizing the standard clinical proton setup. The endogenous contrast available presents opportunities of a new non-invasive biomarker for disease and efficacy of treatment, which is ameliorated by the increased field strength at 7T. CEST has the potential for increased specificity compared to the standard clinical imaging techniques currently probing water protons. The contrast is affected by several tissue properties, such as the concentrations of exchange partners and their rate of proton exchange, whose effects have been only sparsely examined and explored in this review. We have highlighted the background of CEST MRI, its typical implementation strategy, as well as its complications at 7T. Particularly, the application of CEST at higher field is addressed and the benefits of this migration to 7T are shown. The increased field strength will translate to higher achievable resolution, better anatomical coverage, or a decreased imaging time compared to lower field. In addition to signal gains, the chemical dispersion is increased at 7T, facilitating selective saturation, decreasing saturation pulse bandwidth demands, and creating a more favorable exchange regime.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the technologists Debbie Boner, Donna Butler, Leslie McIntosh, and Dave Pennell for their invaluable assistance with scheduling and subject assistance. Numerous people have helped acquire, process, and discuss this data including Elizabeth Asche, Jane Hirtle, Francesca Bagnato, Richard Dortch, Brian Welch, Dan Gochberg, Ram Sriram, Sid Pawate, Ted Towse, and Bruce Damon. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health to J.G. and S.S. Finally, we thank all volunteers for their time and cooperation in the scanner.

Grant Sponsor: NIH #EB001628, EB009120

Contributor Information

Adrienne N. Dula, Email: adrienne.n.dula@vanderbilt.edu.

Seth A. Smith, Email: seth.smith@vanderbilt.edu.

John C. Gore, Email: john.gore@vanderbilt.edu.

References

- 1.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Nmr Imaging of Labile Proton-Exchange. J Magn Reson. 1990 Jan;86(1):164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Zijl PC, Zhou J, Mori N, Payen JF, Wilson D, Mori S. Mechanism of magnetization transfer during on-resonance water saturation. A new approach to detect mobile proteins, peptides, and lipids. Magn Reson Med. 2003 Mar;49(3):440–449. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancu I, Dixon WT, Woods M, Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. CEST and PARACEST MR contrast agents. Acta Radiol. 2010 Oct;51(8):910–923. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.502126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terreno E, Stancanello J, Longo D, et al. Methods for an improved detection of the MRI-CEST effect. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2009 Sep-Oct;4(5):237–247. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Zijl PC, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011 Apr;65(4):927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000 Mar;143(1):79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant RG. The dynamics of water-protein interactions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith SA, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM. Direct Saturation MRI: Theory and Application to Imaging Brain Iron. Magnet Reson Med. 2009 Aug;62(2):384–393. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, van Zijl PCM, Zhou JY. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magnet Reson Med. 2007 Oct;58(4):786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson WA, Freeman AR. Influence of a Second Radio Frequency Field on High-Resolution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1962;37(1):85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheidegger R, Vinogradov E, Alsop DC. Amide proton transfer imaging with improved robustness to magnetic field inhomogeneity and magnetization transfer asymmetry using saturation with frequency alternating RF irradiation. Magn Reson Med. 2011 May 23; doi: 10.1002/mrm.22912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaiss M, Schmitt B, Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. J Magn Reson. 2011 Aug;211(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desmond KL, Stanisz GJ. Understanding quantitative pulsed CEST in the presence of MT. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Aug 19; doi: 10.1002/mrm.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dula AN, Asche EM, Landman BA, et al. Development of chemical exchange saturation transfer at 7T. Magnet Reson Med. 2011;66(3):831–838. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (QUEST and QUESP): Ph calibration for poly-L-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Apr;55(4):836–847. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Wilson DA, Sun PZ, Klaus JA, Van Zijl PC. Quantitative description of proton exchange processes between water and endogenous and exogenous agents for WEX, CEST, and APT experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2004 May;51(5):945–952. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou JY, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med. 2003 Aug;9(8):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou JY, Tryggestad E, Wen ZB, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat Med. 2011 Jan;17(1):130–U308. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulkern RV, Williams ML. The General-Solution to the Bloch Equation with Constant Rf and Relaxation Terms - Application to Saturation and Slice Selection. Med Phys. 1993 Jan-Feb;20(1):5–13. doi: 10.1118/1.597063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pekar J, Jezzard P, Roberts DA, Leigh JS, Jr, Frank JA, McLaughlin AC. Perfusion imaging with compensation for asymmetric magnetization transfer effects. Magn Reson Med. 1996 Jan;35(1):70–79. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narvainen ML, Hubbard PL, et al. A method for T2-selective saturation to cancel out macromolecular magnetization transfer in z-spectroscopy. Paper presented at: International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Berlin. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman JI, McMahon MT, Stivers JT, Van Zijl PC. Indirect detection of labile solute proton spectra via the water signal using frequency-labeled exchange (FLEX) transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2010 Feb 17;132(6):1813–1815. doi: 10.1021/ja909001q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 19;105(7):2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PC. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003 Dec;50(6):1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Wen Z, Huang F, et al. Saturation Power Dependence of Amide Proton Transfer Image Contrasts in Human Brain Tumors and Strokes at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22891. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin T, Autio J, Obata T, Kim SG. Spin-locking versus chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI for investigating chemical exchange process between water and labile metabolite protons. Magn Reson Med. 2011 May;65(5):1448–1460. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun PZ, Wang E, Cheung JS, Zhang X, Benner T, Sorensen AG. Simulation and optimization of pulsed radio frequency irradiation scheme for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI-demonstration of pH-weighted pulsed-amide proton CEST MRI in an animal model of acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Mar 24; doi: 10.1002/mrm.22894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun PZ, Benner T, Kumar A, Sorensen AG. Investigation of optimizing and translating pH-sensitive pulsed-chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging to a 3T clinical scanner. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Oct;60(4):834–841. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun PZ, van Zijl PC, Zhou J. Optimization of the irradiation power in chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer experiments. J Magn Reson. 2005 Aug;175(2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Huang J, van Zijl P. Simplified quantitative description of amide proton transfer (APT) imaging during acute ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007 Feb;57(2):405–410. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haris M, Cai K, Singh A, Hariharan H, Reddy R. In vivo mapping of brain myo-inositol. Neuroimage. 2011 Feb 1;54(3):2079–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mougin OE, Coxon RC, Pitiot A, Gowland PA. Magnetization transfer phenomenon in the human brain at 7 T. Neuroimage. 2010 Jan 1;49(1):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Blakeley JO, Hua J, et al. Practical data acquisition method for human brain tumor amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Oct;60(4):842–849. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varma G, Lenkinski RE, Vinogradov E. Keyhole chemical exchange saturation transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2012 Jan 13; doi: 10.1002/mrm.23310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun PZ, Cheung JS, Wang EF, Benner T, Sorensen AG. Fast Multislice pH-Weighted Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) MRI With Unevenly Segmented RF Irradiation. Magnet Reson Med. 2011 Feb;65(2):588–594. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Mar 13;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori S, Abeygunawardana C, van Zijl PC, Berg JM. Water exchange filter with improved sensitivity (WEX II) to study solvent-exchangeable protons. Application to the consensus zinc finger peptide CP-1. J Magn Reson B. 1996 Jan;110(1):96–101. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ceckler T, Maneval J, Melkowits B. Modeling magnetization transfer using a three-pool model and physically meaningful constraints on the fitting parameters. J Magn Reson. 2001 Jul;151(1):9–27. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McConnell HM. Reaction Rates by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1958;28:430. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goffeney N, Bulte JW, Duyn J, Bryant LH, Jr, van Zijl PC. Sensitive NMR detection of cationic-polymer-based gene delivery systems using saturation transfer via proton exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2001 Sep 5;123(35):8628–8629. doi: 10.1021/ja0158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magn Reson Med. 1995 Jul;34(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider E, Glover G. Rapid in vivo proton shimming. Magn Reson Med. 1991 Apr;18(2):335–347. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webb P, Macovski A. Rapid, fully automatic, arbitrary-volume in vivo shimming. Magn Reson Med. 1991 Jul;20(1):113–122. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910200112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun PZ. Simultaneous determination of labile proton concentration and exchange rate utilizing optimal RF power: Radio frequency power (RFP) dependence of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. J Magn Reson. 2010 Feb;202(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Jun;61(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones CK, Polders D, Hua J, et al. In vivo three-dimensional whole-brain pulsed steady-state chemical exchange saturation transfer at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Nov 14; doi: 10.1002/mrm.23141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) Magnet Reson Med. 2000 Nov;44(5):799–802. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<799::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Sun W, Huang J, van Zijl PC. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007 Jun;27(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PC, Pomper MG, Golay X, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Sep;56(3):585–592. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun PZ, Benner T, Copen WA, Sorensen AG. Early Experience of Translating pH-Weighted MRI to Image Human Subjects at 3 Tesla. Stroke. 2010 Oct;41(10):S147–S151. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dula AN, Pawate S, Sriram S, Smith SA. Human ultra high field chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI: what proteins and peptides have to do with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010 Aug;16(8):1011–1011. [Google Scholar]