Abstract

Purpose

This study was designed to evaluate short-term clinical outcomes by comparing hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery with open surgery for right colon cancer.

Methods

Sixteen patients who underwent a hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (HAL-RHC group) and 33 patients who underwent a conventional open right hemicolectomy (open group) during the same period were enrolled in this study with a case-controlled design.

Results

The operation time was 217 minutes in the HAL-RHC group and 213 minutes in the open group (P = 0.389). The numbers of retrieved lymph nodes were similar between the two groups (31 in the HAL-RHC group and 36 in the open group, P = 0.737). Also, there were no significant difference in the incidence of immediate postoperative leukocytosis, the administration of additional pain killers, and the postoperative recovery parameters. First flatus was shown on postoperative days 3.5 in the HAL-RHC group and 3.4 in the open group (P = 0.486). Drinking water and soft diet were started on postoperative days 4.8 and 5.9, respectively, in the HAL-RHC group and similarly 4.6 and 5.6 in the open group (P = 0.402 and P = 0.551). The duration of hospital stay was shorter in the HAL-RHC group than in the open group (10.3 days vs. 13.5 days, P = 0.048). No significant difference in the complication rates was shown between the two groups, and no postoperative mortality was encountered in either group.

Conclusion

The patients with right colon cancer in the HAL-RHC group had similar pathologic and postoperative recovery parameters to those of the patients in the open group. The patients in the HAL-RHC group had shorter hospital stays than those in the open group. Therefore, hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for right-sided colon cancer is feasible.

Keywords: Hand-assisted laparoscopy, Colonic neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Since minimally invasive surgery was pioneered in the early 1980s [1], colorectal surgeons have been faced with a variety of operative techniques, such as open surgery, hand-assisted or conventional laparoscopic surgery, robotic surgery, and single-port laparoscopic surgery [2-4]. All kinds of operations have their own merits. Laparoscopic surgery has many advantages, such as a smaller incision, less pain, a faster recovery, and a shorter hospital stay [1, 3, 5]. On the other hand, limitations, such as its complexity, longer operation time, longer learning curve, lack of tactile feedback, and higher cost, still exist [3, 5].

Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) is a kind of hybrid laparoscopic technique incorporating elements of both the laparoscopic and the traditional open techniques [1, 6-8]. In other words, this procedure is a kind of minimally invasive surgery and has the features of open surgery [1, 6-9]. The most important advantage of HALS is that the surgeon regains tactile feedback. Surgeons can palpate the tumor or organs, and the surgeons' hand can be used for blunt dissection, retraction, control of bleeding, and specimen removal [1-3, 6-14].

Although many studies related to the use of HALS for treating colorectal disease have been performed, few reports comparing HALS to open surgery in patients with right colon cancer have been published. Therefore, this study was designed to compare the short-term outcomes of a hand-assisted laparoscopic and a conventional open right hemicolectomy in patients with right colon cancer.

METHODS

Based on the prospectively-collected colorectal cancer database at our institute, a case-controlled study was designed. Between January 2009 and September 2010, of the patients with an adenocarcinoma on the right colon from the cecum to the proximal transverse colon, 16 patients who underwent a hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (HAL-RHC group) and 33 patients who underwent a conventional open right hemicolectomy (open group) were enrolled as the study and the control groups, respectively. Then control group was selected so as to be case-matched with the HAL-RHC group in the aspects of age, sex, and tumornode-metastasis (TNM) stage during the same period. All patients underwent a curative R0 resection by one experienced surgeon. The patients who underwent an emergent operation because of perforation, obstruction or peritonitis, and so on were excluded.

Surgical techniques

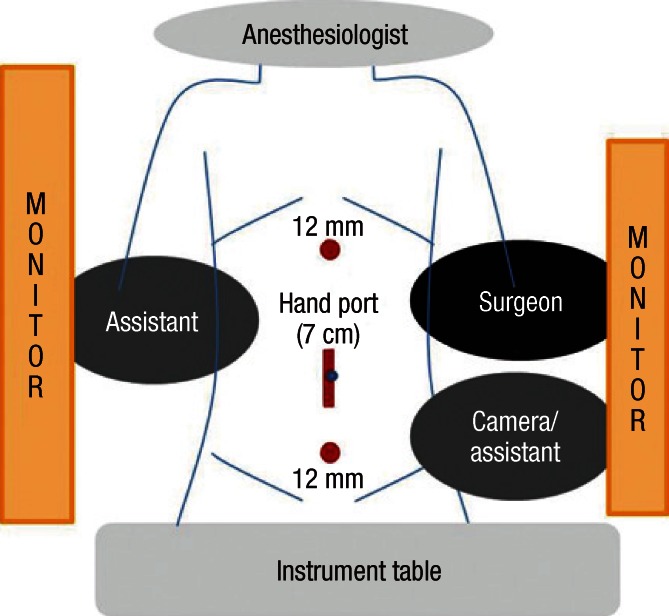

Under endotracheal intubation, a patient was positioned on the surgical table in the supine position. A Foley catheter was inserted, but no nasogastric tube was used routinely. The operative field was prepared in an aseptic manner and draped. The operating room's setup, the location of the laparoscopic port and the skin incision for the HAL-RHC is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Operating-room setup for hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy.

First of all, a mid-midline skin incision with a 6- or 7-cm length was made, centered on the umbilicus. A Gelport (Applied Medical Resources Co., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) was applied to the skin incision. A Gelport is a kind of hand-port device that can maintain the pneumoperitoneum while the surgeon's hand is in the abdominal cavity. Then, CO2 gas was insufflated, and a pneumoperitoneum was made. Under visualization with a 30-degree laparoscope, two 12-mm trocars were inserted into the epigastric and the suprapubic area at the midline. Then, the camera assistant, who was located to the left of patient and to the left of surgeon, inserted the laparoscopic camera via the suprapubic port. The surgeon's left hand was inserted into the intra-abdominal cavity via the hand-port, and the laparoscopic instrument was inserted via the epigastric port. Dissection was started from the right paracolic gutter. The ascending colon was dissected with a lateral-to-medial approach with an electrocoagulation device. After full mobilization of the ascending and proximal transverse colon, the ileocolic, right colic and right branch of the middle colic vessel were ligated with hemoclips or hem-o-Lok (Teleflex Inc., Limerick, PA, USA).

The next steps were similar to those of open surgery. The Gelport was removed, and the terminal ileum and the ascending and transverse colon were exteriorized. The transverse colon and the terminal ileum were resected with sufficient margins from the tumor. Anastomosis was performed using the hand-sewn and end-to-end method or the side-to-side stapled method. After saline irrigation and meticulous hemostasis, a pneumoperitoneum was made using the Gelport; then, anastomosis alignment and complete hemostasis were checked. A drain was not inserted routinely. The two port incisions and the midline incision were closed layer by layer.

Postoperative care

For pain control, intravenous patient-controlled analgesics were routinely applied for all patients for the first 3 days. Additional analgesics were administrated when required. This is recorded as extra pain killers in the tables. Drinking water was started when patients had no abdominal discomfort after first flatus. If they were tolerable to this step, soft diet began. Patients were discharged when soft diet was tolerable and they agreed. Routine laboratory tests were performed on postoperative days 1, 2, 4 and 7; especially, the postoperative white blood cell (WBC) count was checked immediately after surgery. Clinicopathologic, intraoperative and postoperative parameters were statistically analyzed between the HAL-RHC and the open groups.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS ver. 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Summary statistics using the chi-squared test, the two-sample t-test with Welch's correction, and Fisher's exact test were used to compare the HAL-RHC group with the open group. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

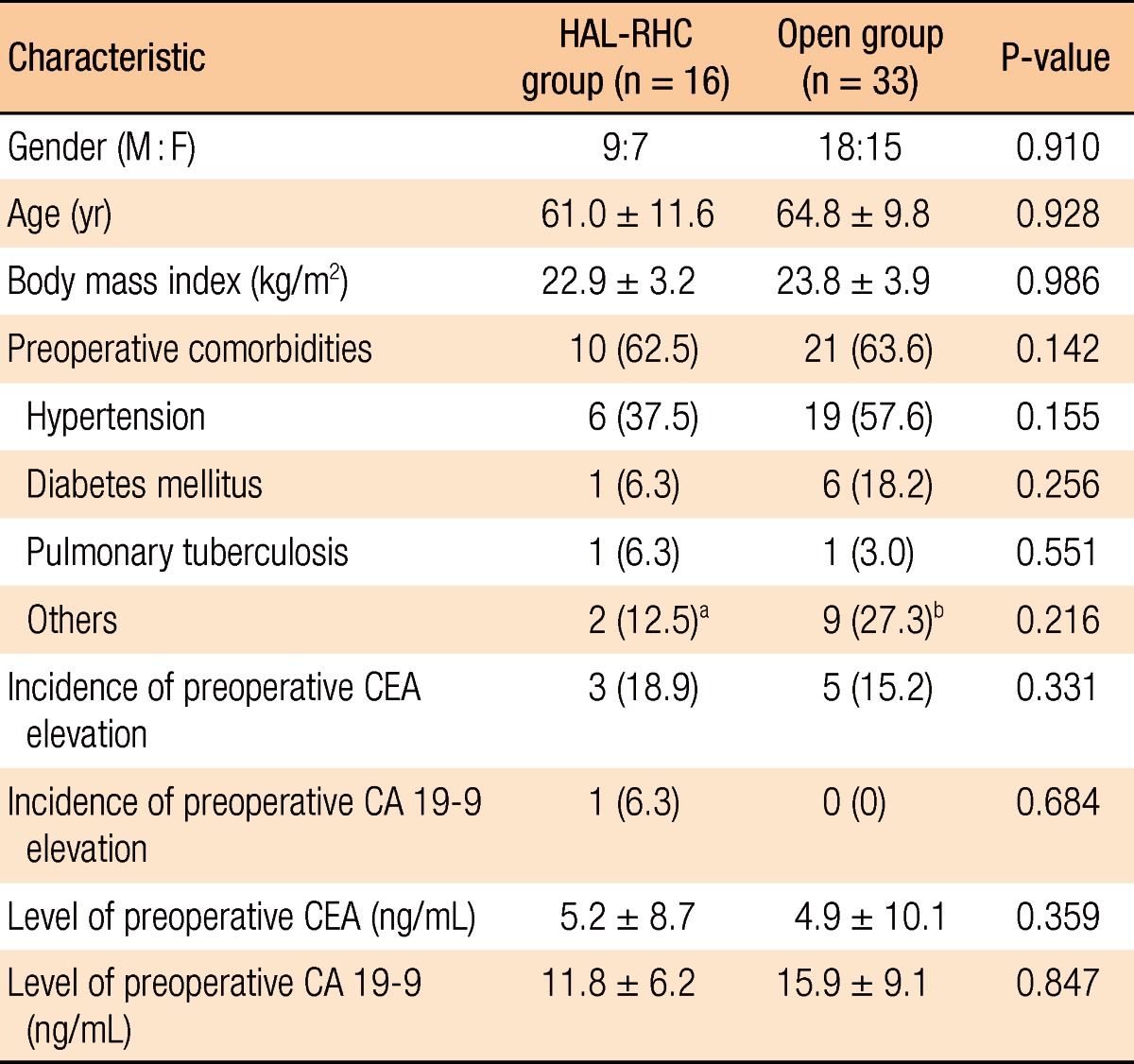

The total 49 cases consisted of 16 cases in the HAL-RHC group and 33 cases in the open group. The gender ratio (male : female) was 9 : 7 in the HAL-RHC group and 18 : 15 in the open group (P = 0.910). The mean age was 61 years in the HALS group and 65 years in the open group (P = 0.928). There were no significant differences in gender, age, preoperative comorbidities, and body mass index between the two groups. Patients' demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

HAL-RHC, hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy; CEA, careinoembryonal antigen; CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

aCerebral infraction, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. bStomach cancer, schizophrenia, atrial septal defect, valvular heart disease, pneumoconiosis, cerebral infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, chronic liver disease.

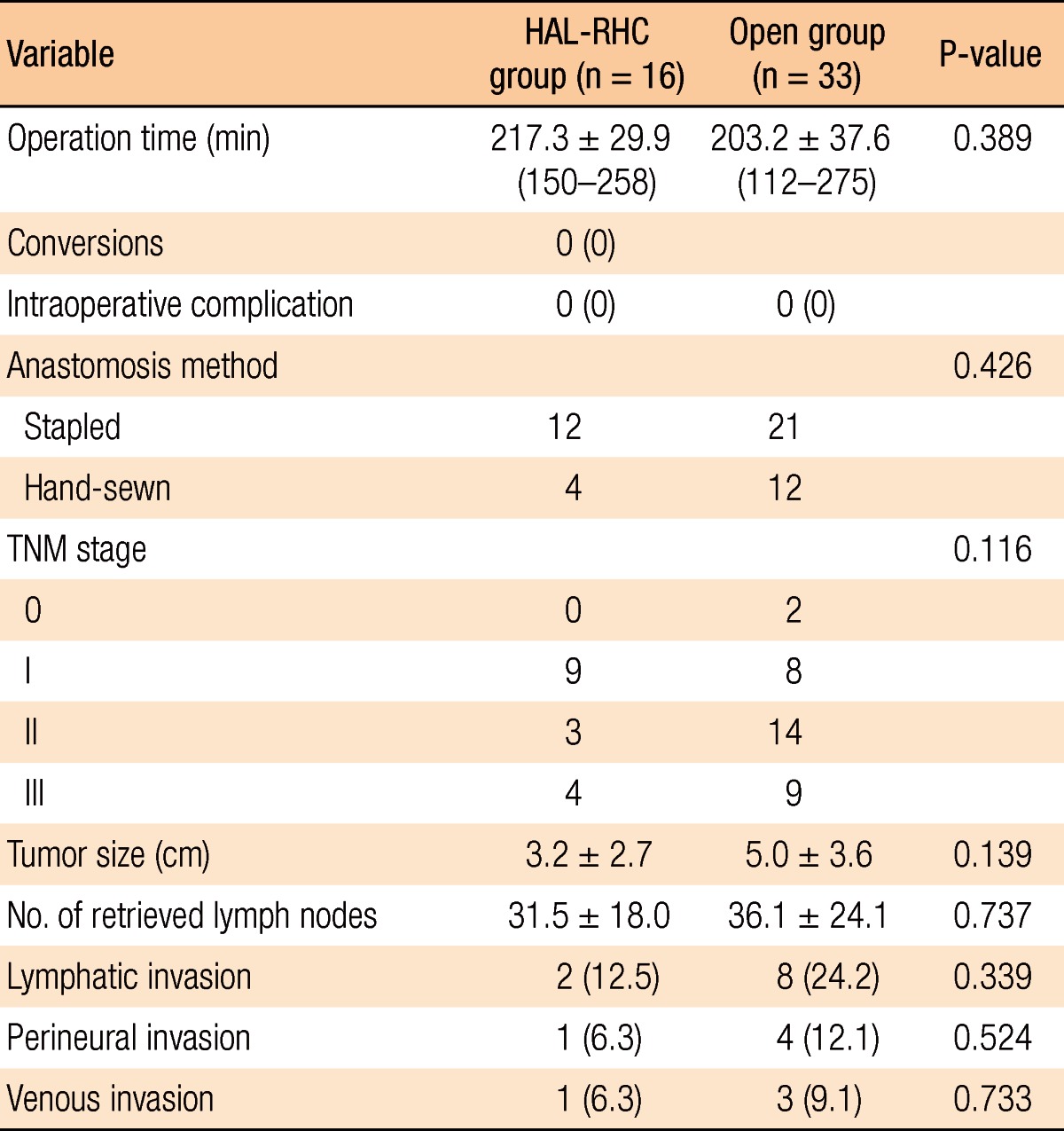

The mean operation time was 217 minutes in the HAL-RHC group and 203 minutes in the open group. It was 14 minutes longer in the HAL-RHC group than in the open group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.389). In the HAL-RHC group, there was no conversion to open surgery. In both group, there were no intraoperative complications, such as ureter injury, hemorrhage, reanastomosis, and so on. Between the two groups, no significant differences were noted in either the distribution of TNM stage or pathologic parameters, such as tumor size, number of retrieved lymph nodes, and lymphovascular or neural invasion. These data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operative and pathologic variables in the HAL-RHC and open group

Vales are presented as mean ± standard deviation (range) or number (%).

HAL-RHC, hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

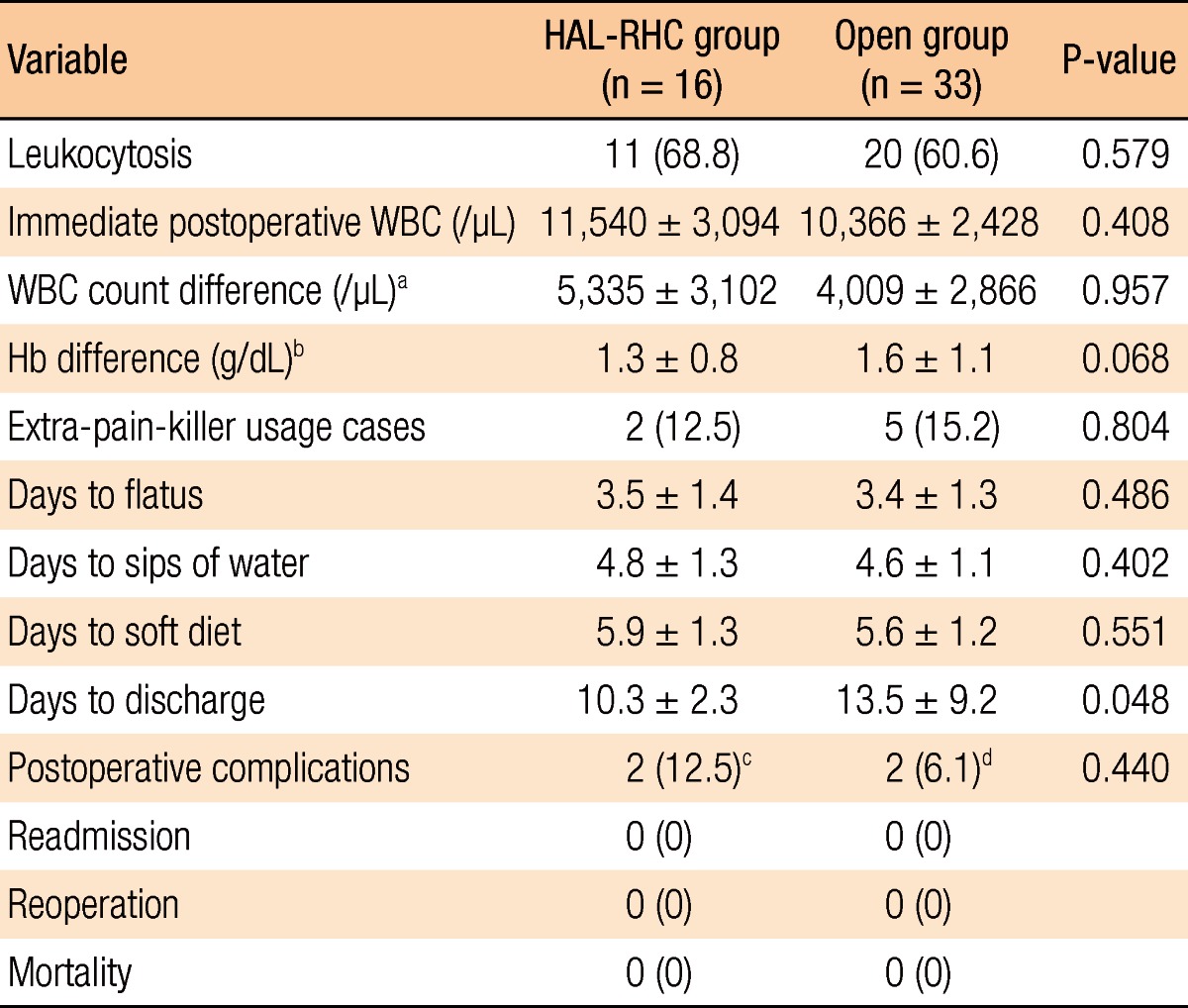

In the aspect of postoperative laboratory data, the incidence of immediate postoperative leukocytosis on the operation day was 68.8% in the HAL-RHC group and 60.6% in the open group (P = 0.579). The mean WBC count was 11,540/µL in the HAL-RHC group and 10,366/µL in the open group (P = 0.408). There were no significant differences in the incidence of postoperative leukocytosis, of the postoperative mean WBC count, the difference between the preoperative and the postoperative WBC counts and the difference in hemoglobin, as shown in Table 3. There were no transfusions during the operations or the postoperative period.

Table 3.

Postoperative laboratory data and recovery parameters

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation

HAL-RHC, hand-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin.

aPostoperative WBC count-preoperative WBC count. bPreoperative Hb-postoperative Hb. cMinor wound problem in 2 cases. dPostoperative ileus and minor wound problem.

Postoperative recovery parameters are presented in Table 3. First flatus was shown on postoperative day 3.5 in the HAL-RHC group and 3.4 in the open group (P = 0.486). Drinking water and soft diet were started on postoperative days 4.8 and 5.9 in the HAL-RHC group, respectively, and on postoperative days 4.6 and 5.6 in the open group (P = 0.402 and P = 0.551). Additional pain killers were administrated to two patients in the HAL-RHC group and five patients in the open group (P = 0.804). Postoperative complications developed in 2 patients in each groups. While minor wound problems were noted in the HAL-RHC group, postoperative ileus and minor wound problems were noted in the open group. All patients recovered after conservative management. No postoperative mortalities or reoperations occurred in either group.

DISCUSSION

According to our data, compared to the patients in the open right hemicolectomy group, those who underwent a HAL-RHC for right colon cancer had similar short-term clinical outcomes and shorter hospital stays. This factor means a faster postoperative recovery, which is a merit of minimally invasive surgery.

By some studies that compared open surgery with HALS for colorectal diseases, the common conclusion was that HALS had better cosmetic effect with a smaller incision, a faster recovery, and a shorter hospital stay [3, 6, 15, 16]. Our data showed similar results, such as a smaller incision and a shorter hospital stay, but there was no significant differences in amounts of additional pain killers administered, first flatus, or beginning of diet.

In our data, the mean of operation times were similar between the two groups. Most studies have reported that the operation time was longer in the HALS group than in the open surgery group [3, 16]. Previous studies included multiple surgeons who performed various types of colorectal operations, for example, anterior resections, right or left hemicolectomies, low anterior resections or total colectomies [3, 6, 16]. In other words, heterogeneous factors were compared [3, 6, 15, 16]. In contrast, this study enrolled a homogeneous group, that is, only colorectal cancer patients who underwent a right hemicolectomy by one experienced colorectal surgeon. Kang et al. [6] reported that operation times were similar between HALS and open surgery in the case of operations by one experienced surgeon. Thus, the longer operation time in the HALS group is mainly due to the lack of surgeon's experience, not the method of operation.

In fact, minimally invasive surgery for colorectal diseases has already been reported to be technically feasible and safe [7, 8, 10, 13, 17, 18]. However, most studies included both benign and malignant colorectal diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases, diverticulitis, sigmoid volvulus, and even colorectal cancer [2, 3, 10, 16, 17, 19]. In the case of malignant disease, not only the feasibility of surgery but also its oncologic safety should be considered and evaluated. Thus, the number of retrieved lymph nodes could be one parameter for evaluating the extent of lymph node dissection. Sheng et al. [3] reported no difference in the numbers of retrieved lymph nodes between the HAL-RHC and the open groups. Our data also demonstrated that the numbers of retrieved lymph nodes were 31 in the HAL-RHC group and 36 in the open group, being more than 12 in both groups.

In many studies comparing HALS with conventional laparoscopic surgery for colorectal diseases, the clinical short-term outcomes were similar between the two groups [4, 8, 18-20]. Nevertheless, some authors suggested that conventional laparoscopic surgery was superior, and HALS was inferior [4, 13, 20]. However, each procedure has its own advantages. In other words, HALS patients had a longer incision and more surgical trauma than the patients with conventional laparoscopic surgery; instead, HALS had a lower conversion rate and allowed tactile sensation through the surgeon's hand to be maintained. In addition, when an unexpected situation developed during the operation, the operator's hand could approach the intraabdominal cavity directly and solve the problem quickly as in open surgery [1, 9, 13, 14, 21]. As mentioned in the introduction, hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery is a kind of hybrid technique, which has the benefits of both laparoscopic and conventional open surgery for the treatment of right colon cancer, even though some surgeons consider HALS to be a bridge from open surgery to laparoscopic surgery.

In conclusion, patients with right colon cancer who underwent a HAL-RHC had not only smaller incisions and shorter hospital stays but also a radicality of lymph-node dissection similar to that in patients with right colon cancer who underwent conventional open surgery. Therefore, a hand-assisted right hemicolectomy for the treatment of right colon cancer is safe and feasible, and can be considered as an alternative operation to conventional open surgery.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Darzi A. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:999–1004. doi: 10.1007/s004640000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne GH, Leahy PF. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: evolution to a clinically useful technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:753–765. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheng QS, Lin JJ, Chen WB, Liu FL, Xu XM, Lin CZ, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open right hemicolectomy: short-term outcomes in a single institution from China. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:267–271. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182516577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yun HR, Cho YK, Cho YB, Kim HC, Yun SH, Lee WY, et al. Comparison and short-term outcomes between hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery and conventional laparoscopic surgery for anterior resections of left-sided colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:975–981. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HALS Study Group. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery vs standard laparoscopic surgery for colorectal disease: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang JC, Chung MH, Chao PC, Yeh CC, Hsiao CW, Lee TY, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy vs open colectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:577–581. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcello PW. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: a helping hand? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:125–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcello PW, Fleshman JW, Milsom JW, Read TE, Arnell TD, Birnbaum EH, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic vs. laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:818–826. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darzi A. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cima RR, Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Pattana-Arun J, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, et al. Utility and short-term outcomes of hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a single-institution experience in 1103 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1076–1081. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182155904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozturk E, da Luz Moreira A, Vogel JD. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: the learning curve is for operative speed, not for quality. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10 Online):e304–e309. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakajima K, Milsom JW, Margolin DA, Szilagy EJ. Use of the surgical towel in colorectal hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) Surg Endosc. 2004;18:552–553. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanna GB, Elamass M, Cuschieri A. Ergonomics of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:92–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanelli JR, Kelly JJ, Litwin DE. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery in the United States: an overview. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orenstein SB, Elliott HL, Reines LA, Novitsky YW. Advantages of the hand-assisted versus the open approach to elective colectomies. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1364–1368. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu CC. Letter 1: short-term outcomes from a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer (Br J Surg 2009;96:1458-1467) Br J Surg. 2010;97:789. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aalbers AG, Doeksen A, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, Bemelman WA. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open approach in colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan I, You YN, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Barnes SA, et al. Hand-assisted versus laparoscopic-assisted colorectal surgery: Practice patterns and clinical outcomes in a minimally-invasive colorectal practice. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:739–743. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Targarona EM, Gracia E, Garriga J, Martínez-Bru C, Cortes M, Boluda R, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing conventional laparoscopic colectomy with hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy: applicability, immediate clinical outcome, inflammatory response, and cost. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:234–239. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datta V, Bann S, Hernandez J, Darzi A. Objective assessment comparing hand-assisted and conventional laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:414–417. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southern Surgeons' Club Study Group. Handoscopic surgery: a prospective multicenter trial of a minimally invasive technique for complex abdominal surgery. Arch Surg. 1999;134:477–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]