Abstract

Aims

Digoxin is recommended for long-term rate control in paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation (AF). While some analyses suggest an association of digoxin with a higher mortality in AF, the intrinsic nature of this association has not been examined in propensity-matched cohorts, which is the objective of the current study.

Methods and results

In Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM), 4060 patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF were randomized to rate (n = 2027) vs. rhythm (n = 2033) control strategies. Of these, 1377 received digoxin as initial therapy and 1329 received no digoxin at baseline. Propensity scores for digoxin use were estimated for each of these 2706 patients and used to assemble a cohort of 878 pairs of patients receiving and not receiving digoxin, who were balanced on 59 baseline characteristics. Matched patients had a mean age of 70 years, 40% were women, and 11% non-white. During the 3.4 years of the mean follow-up, all-cause mortality occurred in 14 and 13% of matched patients receiving and not receiving digoxin, respectively [hazard ratio (HR) associated with digoxin use: 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.83–1.37; P = 0.640]. Among matched patients, digoxin had no association with all-cause hospitalization (HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.85–1.09; P = 0.510) or incident non-fatal cardiac arrhythmias (HR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.37–2.23; P = 0.827). Digoxin had no multivariable-adjusted or propensity score-adjusted associations with these outcomes in the pre-match cohort.

Conclusions

In patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF, we found no evidence of increased mortality or hospitalization in those taking digoxin as baseline initial therapy.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Digoxin, Hospitalization, Mortality, Propensity score

See pages 1465 and 1468 for the editorial comments on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht087 and doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs483)

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in older adults.1 The European Society of Cardiology guideline for the management of AF recommends digoxin for long-term rate control in patients with paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF.2 In the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) trial, the use of a rate-control strategy was associated with a trend towards decreased mortality in patients with AF, which was significant in those 65 years of age or older.3 Digoxin was one of the four rate-control drugs in AFFIRM. However, patients were not randomized to individual rate-control drugs, but instead to a rate-control or rhythm-control strategy. The effect of digoxin or other rate-control drugs on mortality in AF has not been examined in randomized clinical trials. Findings from a post hoc analysis of the AFFIRM data reported in 2004 by the AFFIRM investigators suggested that digoxin use was associated with higher all-cause mortality [adjusted hazard ratio (HR): 1.42; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.09–1.86].4

A recent post hoc analysis of the AFFIRM data by Whitbeck et al.,5 reported a similar association of digoxin with a higher all-cause mortality in AF (adjusted HR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.19–1.67), which has resulted in substantial media attention including calls for the regulatory review of the safety of digoxin.6–8 However, in both studies, digoxin use was analysed using a time-dependent treatment indicator. A fundamental assumption in modelling the effect of a time-dependent treatment on survival is that the change in treatment during the follow-up occurs in a random fashion.9 However, since changes in digoxin use over time cannot be assumed to occur at random, but instead may be related to worsening health conditions, such as incident heart failure (HF) during the follow-up, the resulting confounding over time can bias outcome assessment.

Propensity score matching, developed by Rosenbaum and Rubin,11,12 can be used to design observational studies via retrospective outcome-blinded assembly of matched cohorts that are well-balanced across treatment groups on all measured baseline characteristics.10,11 To determine whether the reported association of digoxin with a higher mortality in patients with AF in AFFIRM reflected an intrinsic adverse effect of digoxin or represented a confounded association due to bias by indication, we designed a study based on the propensity score matching approach similar to that used in our prior studies.12–15

Methods

Study design and participants

We used a public-use copy of the AFFIRM data obtained from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The design and results of the AFFIRM trial have been previously reported.3,16,17 Briefly, 4060 patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF were randomized to receive rate-control (n = 2027) vs. rhythm-control (n = 2033) strategies. Patients with permanent AF were not included in AFFIRM as patients were required to have a reasonable chance to be successful with rhythm-control. Therefore, patients with AF of >6 months duration were included only if they had any intervening sinus rhythm that lasted at least 24 h. Patients younger than 65 years were included if they had one of the following risk factors for stroke or death: hypertension, diabetes, HF, previous stroke, previous transient ischemic attack, systemic embolism, left atrial enlargement by echocardiography, or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. The primary endpoint in the AFFIRM trial was all-cause mortality and patients were followed up to 6 years, ending on 31 October 2001.

Use of digoxin

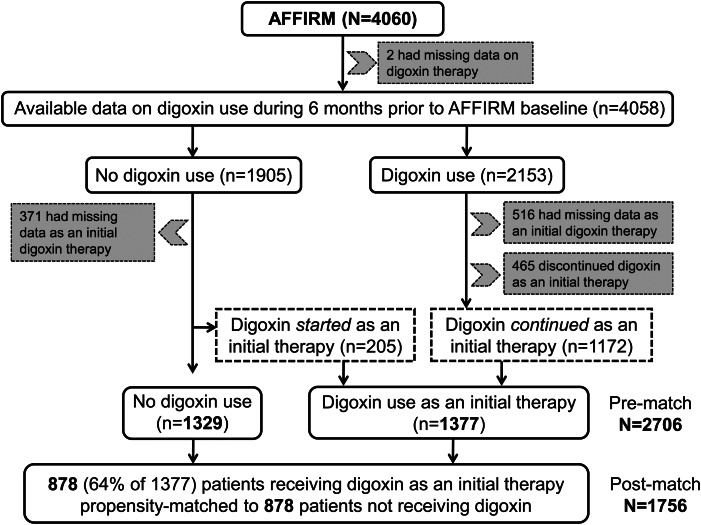

Digoxin was one of the four rate-control drugs used in the AFFIRM trial, the other three being beta-blockers and the two non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, verapamil, and diltiazem. These drugs were chosen by treating physicians, and could be used alone or in combination. In the AFFIRM data, there are two distinct variables on digoxin use: (i) use in the 6 month prior to baseline, and (ii) use as an initial therapy at baseline. The use of digoxin at baseline implies their use at the time of randomization to rate- vs. rhythm-control strategies. However, we prefer to use the word ‘‘baseline’’ to avoid the connotation that patients were randomized to digoxin.18 Of the 2153 patients receiving digoxin during the 6 months prior to baseline, 1172 reported on-going treatment, 465 reported discontinuation of digoxin before baseline, and data on the baseline use of digoxin were not available in 516 patients (Figure 1). Of 1905 patients who did not receive digoxin during the 6 months prior to baseline, new digoxin therapy was initiated at baseline in 205 patients, was not initiated in 1329 patients, and data on initiation were not available for 371 patients (Figure 1). Thus, a total of 1377 (1172 + 205) patients were considered to have received digoxin as an initial therapy at baseline by AFFIRM investigators,3 and are the primary focus of the current analysis (Figure 1). As an initial therapy, digoxin was used alone in 16%, along with a beta-blocker in 14%, and along with a calcium channel blocker in 14% of patients.19 Overall rate control with digoxin alone at rest and during exertion was achieved in 68 and 70% of patients, respectively.19

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying assembly of study cohorts.

Outcomes

As in the AFFIRM trial, the primary outcome for the current analysis was all-cause mortality during a mean follow-up of 3.5 years. Because non-adherence to digoxin use increased during the follow-up, we also examined the association of digoxin use with all-cause mortality at 1, 2, 3, and 12 months of follow-up. We also studied the association of digoxin with all-cause hospitalization and incident non-fatal arrhythmias through the end of the study. Incident non-fatal arrhythmias included torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and resuscitated cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, electromechanical dissociation, bradycardia, or other reasons.

Assembly of a balanced study cohort

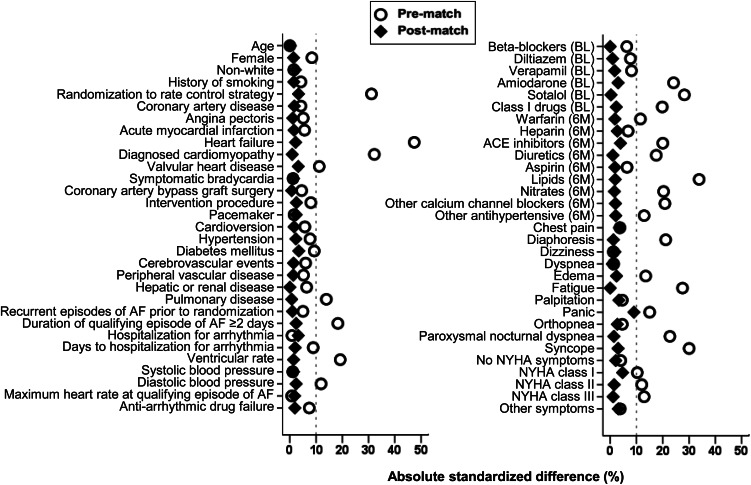

To attenuate between-group imbalances on baseline patient characteristics, we used propensity scores to assemble a cohort in which patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as an initial therapy at baseline would be well balanced on all key measured baseline confounders.10,11 We estimated the propensity score for the receipt of digoxin as an initial therapy at baseline for each of the 2706 participants, using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model in which digoxin administration was the dependent variable and the 59 variables presented in Figure 2 were included as covariates.20,21 Propensity score models are sample-specific adjusters and are not intended to be used for out-of-sample prediction or estimation of coefficients.15,22,23 As such, measures of fitness and discrimination are irrelevant for the assessment of the propensity score's effectiveness. Instead, we assess the improvement in balance across covariates—measured here by absolute values of standardized differences in means (or proportions) of each covariate across the exposure group, expressed as a percentage of the pooled standard deviation. We plot these standardized differences before and after matching as a Love plot.24,25 Absolute standardized differences <10% are considered inconsequential and 0% indicates no residual bias.

Figure 2.

Love plot displaying absolute standardized differences for 59 baseline characteristics between patients with atrial fibrillation receiving and not receiving digoxin as initial baseline therapy in AFFIRM, before and after propensity score matching (NYHA = New York Heart Association; BL = Therapy at baseline or at randomization to rate vs. rhythm control strategies; 6M = Therapy during 6 months prior to randomization to rate vs. rhythm control strategies).

Using a greedy matching protocol, we then assembled a cohort of 878 pairs of patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as an initial therapy at baseline.26,27 Compared with pre-match patients, those in the matched cohort showed substantially improved balance (in terms of reduced absolute standardized differences) across the 59 baseline characteristics. To determine whether the results of our analysis was confounded by biases associated with prevalent drug use,28,29 we conducted two separate sensitivity analyses. Because baseline blood pressure and heart rate may have been affected by the prevalent use of digoxin and their adjustment may introduce selection bias,28 we assembled a second set of balanced-matched cohort of 890 pairs of patients based on propensity scores estimated using a model that excluded those covariates. Then, we assembled a balanced matched cohort of 137 pairs of patients based on 205 patients receiving new digoxin therapy and 1329 patients not receiving digoxin at baseline. Finally, for a more direct comparison of our results with those by Whitbeck et al.,5 we assembled another balanced-matched cohort of 1454 pairs of patients based on 2153 and 1905 patients receiving and not receiving digoxin during the 6 months prior to baseline, respectively.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analyses, Pearson's χ2 test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, paired sample t-test, and McNemar's test were used as appropriate for pre- and post-match between-group comparisons. To estimate the association of the two treatment groups with outcomes, we used Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazard analyses. Our Cox models were fitted with and without accounting for our matched pairs through strata. To examine the association of digoxin with all-cause mortality at 1, 2, 3, and 12 months of follow-up, we used Cox regression models censoring times beyond their respective time frames. To confirm any significant association of digoxin with our outcomes, we performed formal sensitivity analyses to quantify the degree of a hidden bias that would need to be present to invalidate such an association.30 Planned subgroup analyses were used to assess the homogeneity of the association of digoxin with total mortality. To determine whether the association of digoxin with total mortality varied based on whether digoxin was used as a monotherapy or in combination with beta-blockers or the two non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, we examined those associations using patients receiving no rate-control drugs as references. We also examined the association of initial digoxin therapy with all-cause mortality in the full group of 2706 patients who had information on the baseline use of digoxin as initial therapy using three different approaches: (i) unadjusted, (ii) multivariable-adjusted (entering all covariates displayed in Figure 2) and (iii) propensity score-adjusted. All statistical tests were two-tailed and a P-value <0.05 was considered significant. All data analyses were performed using SPSS-21 for Windows (Release 2012, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Matched patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as an initial therapy had a mean age of 70 years, 40% were women, 11% were non-whites, and 40% had prior hospitalizations due to arrhythmias. Baseline characteristics of these patients are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. Post-match standardized differences for all 59 measured covariates were <10% suggesting substantial balance across the groups (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by the use of digoxin as initial therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation during randomization (to rate vs. rhythm control strategy) in AFFIRM, before and after propensity-matching

| Variables Mean ± SD or n (%) | Before propensity-matching |

After propensity-matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin use |

P-value | Digoxin use |

P-value | |||

| No (n = 1329) | Yes (n = 1377) | No (n = 878) | Yes (n = 878) | |||

| Age (years) | 70 ± 8 | 70 ± 8 | 0.998 | 70 ± 8 | 70 ± 8 | 0.970 |

| Age 65 years or older | 1007 (76) | 1053 (77) | 0.670 | 679 (77) | 690 (79) | 0.560 |

| Female | 485 (37) | 559 (41) | 0.028 | 349 (40) | 343 (39) | 0.803 |

| Non-whites | 151 (11) | 163 (12) | 0.699 | 104 (12) | 98 (11) | 0.713 |

| History of smoking | 147 (11) | 171 (12) | 0.273 | 99 (11) | 95 (11) | 0.813 |

| Randomization to rate control strategy | 717 (54) | 949 (69) | <0.001 | 356 (41) | 342 (39) | 0.506 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 478 (36) | 523 (38) | 0.278 | 324 (37) | 317 (36) | 0.761 |

| Angina pectoris | 317 (24) | 359 (26) | 0.183 | 216 (25) | 212 (24) | 0.866 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 204 (15) | 240 (17) | 0.144 | 141 (16) | 136 (16) | 0.792 |

| Heart failure | 161 (12) | 428 (31) | <0.001 | 147 (17) | 140 (16) | 0.664 |

| Valvular heart disease | 136 (10) | 191 (14) | 0.004 | 96 (11) | 105 (12) | 0.538 |

| Symptomatic bradycardia | 84 (6) | 91 (7) | 0.761 | 57 (7) | 54 (6) | 0.847 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 157 (12) | 183 (13) | 0.247 | 111 (13) | 109 (12) | 0.942 |

| Interventional procedure | 126 (10) | 100 (7) | 0.037 | 76 (9) | 70 (8) | 0.661 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 79 (6) | 87 (6) | 0.685 | 52 (6) | 57 (7) | 0.699 |

| Cardioversion | 526 (40) | 507 (37) | 0.140 | 324 (37) | 331 (38) | 0.762 |

| Hypertension | 979 (74) | 967 (70) | 0.047 | 640 (73) | 631 (72) | 0.675 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 241 (18) | 301 (22) | 0.015 | 168 (19) | 180 (21) | 0.513 |

| Cerebrovascular events | 186 (14) | 165 (12) | 0.119 | 114 (13) | 110 (13) | 0.831 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 82 (6) | 103 (8) | 0.177 | 64 (7) | 61 (7) | 0.856 |

| Hepatic or renal disease | 68 (5) | 91 (7) | 0.099 | 50 (6) | 50 (6) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary disease | 159 (12) | 232 (17) | <0.001 | 123 (14) | 125 (14) | 0.946 |

| Diagnosed cardiomyopathy | 14 (1) | 103 (8) | <0.001 | 14 (2) | 15 (2) | 1.000 |

| Recurrent episodes of AF prior to randomization | 502 (38) | 487 (35) | 0.194 | 303 (35) | 307 (35) | 0.880 |

| Duration of qualifying episode of AF ≥2 days | 867 (65) | 1014 (74) | <0.001 | 592 (67) | 602 (69) | 0.635 |

| Hospitalization for arrhythmia | 566 (43) | 592 (43) | 0.832 | 352 (40) | 366 (42) | 0.524 |

| Days to hospitalization for arrhythmia | 2.0 ± 3.3 | 2.3 ± 3.6 | 0.020 | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 2.1 ± 3.4 | 0.661 |

| Symptoms during atrial fibrillation in the last 6 months | ||||||

| Chest pain | 290 (22) | 337 (25) | 0.102 | 194 (22) | 194 (22) | 1.000 |

| Diaphoresis | 231 (17) | 281 (20) | 0.045 | 163 (19) | 160 (18) | 0.902 |

| Dizziness | 408 (31) | 475 (35) | 0.035 | 286 (33) | 279 (32) | 0.756 |

| Dyspnoea | 626 (47) | 813 (59) | <0.001 | 445 (51) | 458 (52) | 0.555 |

| Leg swelling | 178 (13) | 335 (24) | <0.001 | 143 (16) | 144 (16) | 1.000 |

| Fatigue | 651 (49) | 810 (59) | <0.001 | 473 (54) | 463 (53) | 0.667 |

| Palpitation | 603 (45) | 704 (51) | 0.003 | 416 (47) | 424 (48) | 0.734 |

| Panic | 123 (9) | 156 (11) | 0.076 | 80 (9) | 87 (10) | 0.626 |

| Orthopnoea | 133 (10) | 231 (17) | <0.001 | 106 (12) | 95 (11) | 0.447 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea | 57 (4) | 118 (9) | <0.001 | 46 (5) | 44 (5) | 0.911 |

| Syncope | 41 (3) | 59 (4) | 0.098 | 32 (4) | 35 (4) | 0.801 |

| Other symptoms | 130 (10) | 120 (9) | 0.338 | 78 (9) | 87 (10) | 0.510 |

| Current heart failure status by NYHA class symptoms | ||||||

| Class I | 102 (8) | 192 (14) | 80 (9) | 84 (10) | ||

| Class II | 56 (4) | 130 (9) | <0.001 | 44 (5) | 48 (6) | 0.484 |

| Class III | 11 (1) | 34 (3) | 11 (1) | 9 (1) | ||

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| Ventricular heart rate (b.p.m.) | 72 ± 14 | 74 ± 14 | <0.001 | 73 ± 14 | 73 ± 14 | 0.758 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 ± 19 | 135 ± 19 | 0.765 | 135 ± 19 | 136 ± 19 | 0.769 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 ± 10 | 76 ± 10 | 0.002 | 77 ± 10 | 77 ± 10 | 0.599 |

| Maximum ventricular rate (b.p.m.) | 107 ± 32 | 107 ± 31 | 0.863 | 107 ± 32 | 106 ± 31 | 0.705 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (≥50%)a | 802 (81) | 703 (69) | <0.001 | 520 (79) | 497 (77) | 0.108 |

| Left arterial size (≤4 cm)a | 342 (34) | 364 (35) | 0.796 | 221 (33) | 247 (37) | 0.074 |

aMissing data, not included into model.

Table 2.

Medication history in patients with atrial fibrillation, by the use of digoxin as initial therapy during randomization to rate vs. rhythm control strategy in AFFIRM, before, and after propensity-matching

| Variables, n (%) | Before propensity-matching |

After propensity-matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin use |

P-value | Digoxin use |

P-value | |||

| No (n = 1329) | Yes (n = 1377) | No (n = 878) | Yes (n = 878) | |||

| Rate or rhythm control drugs used as initial therapy | ||||||

| Beta-blocker | 583 (44) | 463 (34) | <0.001 | 366 (42) | 371 (42) | 0.844 |

| Diltiazem | 333 (25) | 352 (26) | 0.762 | 235 (27) | 228 (26) | 0.743 |

| Verapamil | 105 (8) | 104 (8) | 0.735 | 79 (9) | 77 (9) | 0.934 |

| Amiodarone | 243 (18) | 184 (13) | <0.001 | 152 (17) | 144 (16) | 0.654 |

| Sotalol | 223 (17) | 108 (8) | <0.001 | 101 (12) | 101 (12) | 1.000 |

| Class I drugs* | 145 (11) | 131 (10) | 0.230 | 102 (12) | 93 (11) | 0.545 |

| Medications used within 6 months prior to randomization | ||||||

| Warfarin | 1104 (83) | 1216 (88) | <0.001 | 772 (88) | 745 (85) | 0.060 |

| Heparin | 245 (18) | 230 (17) | 0.236 | 144 (16) | 153 (17) | 0.612 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 442 (33) | 609 (44) | <0.001 | 320 (36) | 314 (36) | 0.804 |

| Diuretics | 458 (35) | 676 (49) | <0.001 | 356 (41) | 343 (39) | 0.539 |

| Aspirin | 381 (29) | 370 (27) | 0.296 | 233 (27) | 241 (27) | 0.710 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 351 (26) | 303 (22) | 0.007 | 227 (26) | 209 (24) | 0.339 |

| Nitrate | 204 (15) | 274 (20) | 0.002 | 149 (17) | 144 (16) | 0.797 |

| Other calcium channel blockers | 163 (12) | 115 (8) | 0.001 | 85 (10) | 88 (10) | 0.873 |

| Other anti-hypertensive drugs | 224 (17) | 213 (16) | 0.327 | 134 (15) | 144 (16) | 0.560 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drug failure | 191 (14) | 235 (17) | 0.054 | 140 (16) | 134 (15) | 0.738 |

*Includes disopyramide, quinidine, procainamide, moricizine, flecainide, and propafenone.

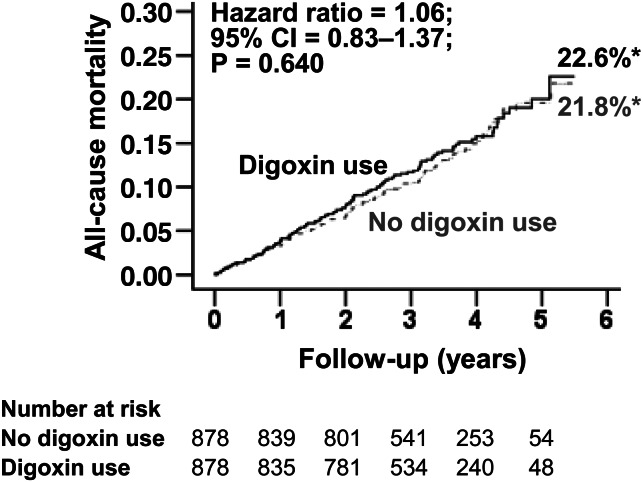

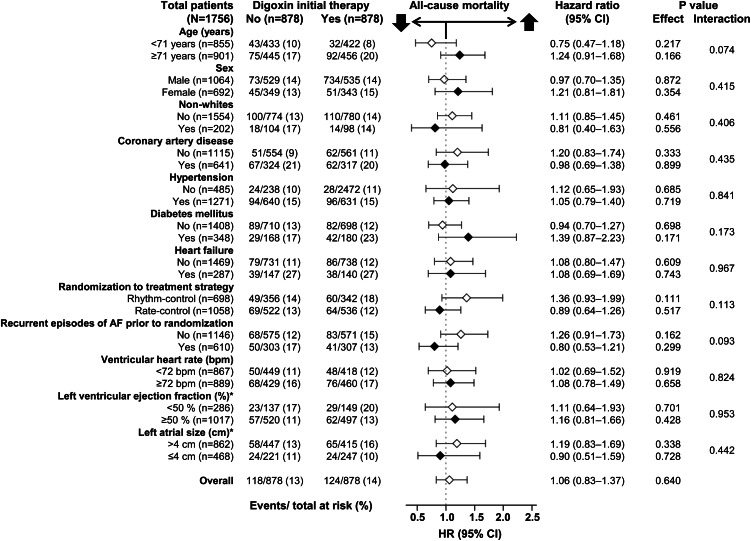

Use of digoxin and all-cause mortality

All-cause mortality occurred in 14 and 13% of matched patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as an initial therapy, respectively (HR when the baseline use of digoxin was compared with their non-use: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.83–1.37; P = 0.640; Table 3 and Figure 3). This association was homogeneous across various subgroups of matched patients including those with and without HF (P for interaction, 0.967; Figure 4). The association of digoxin with total mortality remained unchanged when accounted for matching (HR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.77–1.38; P = 0.825). Digoxin had no association with mortality at 1 month (HR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.09–2.72; P = 0.421), 2 months (HR: 1.00; 95% CI: 0.32–3.09; P = 0.997), 3 months (HR: 1.28; 95% CI: 0.48–3.45; P = 0.620) or 12 months (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.69–1.87; P = 0.612) of follow-up. Digoxin had no association with cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular mortality among matched patients (Table 3). Among the 1780 matched patients based on propensity scores estimated without baseline heart rate and blood pressure, digoxin use had no association with total mortality (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.72–1.17; P = 0.481). Digoxin had no association with total mortality when used as monotherapy or in combination with other rate-control drugs (Table 4).

Table 3.

Association of digoxin use as initial therapy at baseline with outcomes in a propensity-matched cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation enrolled in the AFFIRM trial

| Post-match (n = 1756) | Events (%) |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin use as initial baseline therapy | ||||

| No (n = 878) (%) | Yes (n = 878) (%) | |||

| All-cause mortalitya | 118 (13) | 124 (14) | 1.06 (0.83–1.37) | 0.640 |

| Cardiovascular | 56 (6) | 63 (7) | 1.13 (0.79–1.63) | 0.494 |

| Non-cardiovascular | 48 (6) | 51 (6) | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 0.709 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 516 (59) | 495 (56) | 0.96 (0.85–1.09) | 0.510 |

| Non-fatal arrhythmiasb | 10 (1) | 9 (1) | 0.90 (0.37–2.23) | 0.827 |

aThe sum of cause-specific deaths may not equal total deaths as some deaths were unclassified.

bIncident non-fatal arrhythmias included torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and resuscitated cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, electromechanical dissociation, bradycardia, or other reasons.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plots for all-cause mortality in propensity-matched AFFIRM patients with atrial fibrillation receiving and not receiving digoxin as initial therapy at baseline. *These percentages derived from Kaplan–Meier analysis are different from raw percentages presented in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Association of the use of digoxin as baseline initial therapy with all-cause mortality in subgroups of propensity-matched AFFRIM participants with atrial fibrillation (*based on available data).

Table 4.

All-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation in AFFIRM by the use of digoxin and other rate control drugs as initial baseline therapy

| Hazard ratio (95% CI); P-value |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pre-match (multivariable-adjusted) | Matched | |

| Digoxin and beta-blockers | ||

| Neither | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Digoxin alone | 1.08 (0.82–1.42); 0.578 | 1.06 (0.78–1.46); 0.700 |

| Beta-blockers alone | 0.89 (0.63–1.27); 0.516 | 0.78 (0.54–1.14); 0.202 |

| Both | 0.86 (0.60–1.23); 0.406 | 0.84 (0.58–1.21); 0.338 |

| Digoxin and calcium channel blockers | ||

| Neither | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Digoxin alone | 1.16 (0.87–1.56); 0.313 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52); 0.660 |

| Calcium channel blockers alone | 1.13 (0.81–1.57); 0.468 | 1.10 (0.76–1.57); 0.619 |

| Both | 1.02 (0.72–1.43); 0.930 | 1.15 (0.80–1.65); 0.463 |

Among the 2706 pre-match patients, all-cause mortality occurred in 17% (229/1377) and 13% (171/1329) of patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as an initial therapy, respectively (HR when the baseline use of digoxin was compared with their non-use: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.04–1.54; P = 0.022). However, this association became non-significant after multivariable adjustment (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 0.83–1.30; P = 0.738) and adjustment for propensity scores (HR: 0.95: 95% CI: 0.76–1.18; P = 0.631).

Propensity-matched (based on 274-matched patients) and propensity-adjusted (based on 1534 pre-match patients) HRs for all-cause mortality associated with new digoxin therapy were 0.60 (95% CI: 0.33–1.11; P = 0.102) and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.59–1.52; P = 0.818), respectively. Propensity-matched (based on 2908-matched patients) and propensity-adjusted (based on 4058 pre-match patients) HRs for all-cause mortality associated with digoxin therapy during the 6 months prior to baseline were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.81–1.18; P = 0.785) and 1.01 (95% CI: 0.86–1.19; P = 0.881), respectively.

Use of digoxin and all-cause hospitalization

All-cause hospitalization occurred in 56 and 59% of matched patients receiving and not receiving digoxin as baseline initial therapy, respectively (HR associated with digoxin use: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.85–1.09; P = 0.510; Table 3). Digoxin had no multivariable-adjusted or propensity-adjusted associations with all-cause hospitalization among the 2706 pre-match patients. Propensity-matched (based on 274 matched patients) and propensity-adjusted (based on 1534 pre-match patients) HRs for all-cause hospitalization associated with new digoxin therapy were 0.69 (95% CI: 0.51–0.95; P = 0.022) and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68–1.10; P = 0.227), respectively. Propensity-matched (based on 2908 matched patients) and propensity-adjusted (based on 4058 pre-match patients) HRs for all-cause hospitalization were 1.05 (95% CI: 0.95–1.15; P = 0.356) and 1.02 (95% CI: 0.93–1.11; P = 0.707), respectively.

Use of digoxin and incident non-fatal arrhythmias

Incident non-fatal arrhythmias (sustained ventricular tachycardia, torsades de pointes, and resuscitated cardiac arrest) occurred in 1% of matched patients in each group receiving and not receiving digoxin (HR associated with digoxin use: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.37–2.23; P = 0.827). Digoxin had no multivariable-adjusted or propensity-adjusted associations with incident non-fatal arrhythmias among the 2706 pre-match patients.

Mortality in patients excluded from analysis

Overall, the 1352 patients who were excluded from our analysis had a higher unadjusted mortality (19.6%) vs. the 2706 who were included (14.8%; P < 0.001). Mortality was highest (23%) among the 516 patients who were receiving digoxin during the 6 months prior to baseline but were excluded due to missing data for digoxin use as initial therapy. In contrast, 18% of the 371 patients who were not receiving digoxin before baseline but had missing data for digoxin use as initial therapy died and 17% of the 465 patients who received digoxin during the 6 months prior to baseline but not as initial therapy died.

Discussion

Findings from the current study demonstrate that in a propensity-matched balanced cohort of patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF in AFFIRM, the use of digoxin had no association with mortality, hospitalization, or incident non-fatal arrhythmias. These findings are consistent with those of the main AFFIRM trial in which patients in the rate-control group had a trend towards lower mortality. There is no evidence of survival benefit from digoxin or any of the other three rate-control drugs in AF and the higher mortality in the rhythm-control group was likely due to adverse effects arising from some aspects of the rhythm-control strategy, such as interruption of anticoagulation or adverse effects of anti-arrhythmic drugs. Currently, there are no data regarding the efficacy of digoxin in AF and we found no evidence that digoxin use for a long-term rate control was associated with a higher mortality in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF.

Bias by indication is a potential explanation for the unadjusted association of digoxin use with higher mortality. Before matching, 31% of the patients receiving digoxin had HF (vs. 12% of those not receiving), suggesting that the higher unadjusted mortality in patients given digoxin reflected a higher prevalence of HF rather than a treatment effect. This view was supported by a post hoc analysis of the pre-match data in which adjustment for baseline HF alone reduced the digoxin-associated unadjusted HR from 1.26 to 1.00 (95% CI: 0.81–1.22; P = 0.972), which is consistent with multivariable-adjusted HRs observed by us and reported by Whitbeck et al.5 The consistency of these pre-match adjusted associations with those from the propensity-matched balanced cohort suggest that the exclusion of patients during matching process may not explain the different findings from the present study compared with those presented in the two prior studies.4,5 Although prevalent drug use may introduce bias due to its effect on baseline confounders and left censoring,28,29 this is also unlikely to explain the higher mortality observed in the two prior studies,4,5 as most patients receiving digoxin in the current analysis were prevalent users.

A more plausible explanation of digoxin-associated higher mortality in the prior two studies is their use of digoxin as a time-dependent treatment variable.4,5 As mentioned earlier, the effect of a time-dependent treatment on survival is only valid in situations where the changes in treatment over time is random and not related to health deteriorations.9 If treatment with digoxin was continued for sicker patients, many of whom had HF and those who developed HF during the follow-up, then the observed higher mortality associated with digoxin use is not a real treatment effect, but a confounded association due to a higher sickness burden. In AFFIRM, decisions regarding choice of rate-control drugs and their dosages were left to the primary care physicians at the local site.16 Findings from our Table 1 suggest that of the 589 (161 + 428) pre-match patients with HF 428 (73%) were receiving digoxin at baseline, while of the 2117 pre-match AF patients without HF, 949 (45%) received digoxin. If this practice pattern continued during the follow-up, digoxin may also have been selectively continued or initiated in patients who developed new-onset HF during the follow-up.31

We observed that digoxin had no association with mortality in AF patients with HF, which is consistent with the effect of digoxin in chronic HF patients without AF.32 Digoxin also does not increase mortality in HF patients with preserved ejection fraction.33 The presence of AF does not appear to have independent association with mortality in HF,34,35 and currently there is no evidence to suggest that the effect of digoxin in HF might vary based on the presence or absence of AF. Digoxin in lower doses may work as a neurohormonal modulator,36–38 and may reduce mortality in HF at serum digoxin concentration (SDC) 0.5–0.9 ng/mL.13,39–41 The AFFIRM protocol encouraged SDC ≥1 ng/mL, which has been shown to have no independent association with mortality in HF.13,42 As in HF, AF is also associated with neurohormonal activation and there is growing evidence that neurohormonal blockade may play an important role in the prevention and treatment of AF.43,44 Future prospective randomized clinical trials need to examine if low-dose digoxin may improve outcomes in older adults with AF.

Although new drugs and procedure-based AF therapies continue to evolve,2 and the value of a strict rate-control strategy is being questioned,45 rate control may still play an important role in AF therapy, especially among the growing older AF population. Both European and US national AF guidelines recommend the use of digoxin for long-term rate control in paroxysmal, persistent and permanent AF, especially in patients with a sedentary lifestyle.2,46 In AFFIRM, cumulative achievement of an adequate heart rate control with digoxin monotherapy was similar to beta-blocker monotherapy.19 Similar effects were also seen in patients with AF and HF, although in these patients therapy with both drugs was superior to monotherapy with either drug.47,48 Considering that digoxin is remarkably free of side effects, when used appropriately, it may be an attractive choice for patients with AF, especially among those who have other relative contra-indication to drugs like beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. Findings from the current analysis of the AFFIRM data suggest that there is no evidence to question the use of digoxin or reassess its role in the management of AF.

Our study has several limitations. Post hoc analysis of the association of digoxin with outcomes was not pre-specified in the AFFIRM protocol. It is possible that our rigorous matching process excluded patients who were receiving digoxin in higher doses or in whom digoxin may be deleterious. The high mortality of the patients excluded from our analysis may limit generalizability to patients dissimilar to those included in our analysis. However, we found similar results when multivariable-adjusted models were used in the pre-match data and when we repeated our analysis including the excluded patients. Although the 13.8% total mortality in our matched cohort was slightly lower than the 16.4% total mortality in AFFIRM,3 several of our subgroups had a higher mortality and, yet no higher digoxin-associated mortality. Findings from HF patients suggest that the benefit of digoxin may be more pronounced in high-risk patients with poor outcomes.49 We had no data on adherence during the follow-up and crossover during the follow-up would be expected to underestimated the true associations.50 However, this is unlikely as we found no associations during early months of follow-up when adherence would be expected to be higher. Other limitations include the lack of data on digoxin dose and serum concentration.

In conclusion, in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF enrolled in the AFFIRM trial, we found no evidence of an increased risk of mortality or hospitalization among those receiving digoxin for rate control, either as monotherapy or in combination with other rate-control drugs. These findings do not support the recent suggestion that the use of digoxin in AF should be questioned nor support that there is a need to reassess the role of digoxin in the management of AF in patients with and without HF.

Funding

This work was not supported by any external grant or fund. A.A. was in part supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants (R01-HL085561, R01-HL085561-S and R01-HL097047) from the NHLBI and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama.

Conflict of interest: M.G. has been a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare AG, CorThera, Cytokinetics, DebioPharm S.A., Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Trevena Therapeutics. All other authors had no related interest to declare.

References

- 1.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH European Heart Rhythm A, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic S. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB, Kellen JC, Greene HL, Mickel MC, Dalquist JE, Corley SD The AFFIRM Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Geller N, Greene HL, Josephson RA, Kellen JC, Klein RC, Krahn AD, Mickel M, Mitchell LB, Nelson JD, Rosenberg Y, Schron E, Shemanski L, Waldo AL, Wyse DG Investigators A. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation. 2004;109:1509–1513. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121736.16643.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitbeck MG, Charnigo RJ, Khairy P, Ziada K, Bailey AL, Zegarra MM, Shah J, Morales G, Macaulay T, Sorrell VL, Campbell CL, Gurley J, Anaya P, Nasr H, Bai R, Di Biase L, Booth DC, Jondeau G, Natale A, Roy D, Smyth S, Moliterno DJ, Elayi CS. Increased mortality among patients taking digoxin analysis from the AFFIRM study. Eur Heart J. Advance Access published November 27, 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs348. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes S. Increased Mortality with Digoxin in AF. 30 November 2012. Montreal: HeartWire. Medscape, LLC (‘Medscape’); http://www.theheart.org/article/1481335.do. 15 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittman G. Deaths More Common on Popular Heart Drug: Study. 28 November 2012. New York: Reuters Health; Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/28/us-deaths-more-idUSBRE8AR0KO20121128. 15 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC, Ahmed A, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin for patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: paradise lost or not? Eur Heart J. Advance Access published January 16, 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs483. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher LD, Lin DY. Time-dependent covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:145–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, Gambassi G, Dell'Italia LJ, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M, Allman RM, Meleth S, Bourge RC. Heart failure, chronic diuretic use, and increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–1439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, Adams KF, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:178–186. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinze G, Juni P. An overview of the objectives of and the approaches to propensity score analyses. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1704–1708. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC. Primer on statistical interpretation or methods report card on propensity-score matching in the cardiology literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:62–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.790634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The AFFIRM Investigators. Atrial fibrillation follow-up investigation of rhythm management—the AFFIRM study design. The Planning and Steering Committees of the AFFIRM study for the NHLBI AFFIRM investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1198–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The AFFIRM Investigators. Baseline characteristics of patients with atrial fibrillation: the AFFIRM Study. Am Heart J. 2002;143:991–1001. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.122875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luscher TF. In search of the right word: a statement of the HEART Group on scientific language. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:7–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olshansky B, Rosenfeld LE, Warner AL, Solomon AJ, O'Neill G, Sharma A, Platia E, Feld GK, Akiyama T, Brodsky MA, Greene HL Investigators A. The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study: approaches to control rate in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed A, Fonarow GC, Zhang Y, Sanders PW, Allman RM, Arnett DK, Feller MA, Love TE, Aban IB, Levesque R, Ekundayo OJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Bakris GL, Rich MW. Renin-angiotensin inhibition in systolic heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2012;125:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel K, Fonarow GC, Kitzman DW, Aban IB, Love TE, Allman RM, Gheorghiade M, Ahmed A. Angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes in real-world older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a propensity-matched inception cohort clinical effectiveness study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:1179–1188. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity scores in cardiovascular research. Circulation. 2007;115:2340–2343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahle C, Adamopoulos C, Ekundayo OJ, Mujib M, Aronow WS, Ahmed A. A propensity-matched study of outcomes of chronic heart failure (HF) in younger and older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Zile M, Sanders PW, Patel K, Zhang Y, Aban IB, Love TE, Fonarow GC, Aronow WS, Allman RM. Renin-angiotensin inhibition in diastolic heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2013;126:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed A, Zannad F, Love TE, Tallaj J, Gheorghiade M, Ekundayo OJ, Pitt B. A propensity-matched study of the association of low serum potassium levels and mortality in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1334–1343. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippatos GS, Ahmed MI, Gladden JD, Mujib M, Aban IB, Love TE, Sanders PW, Pitt B, Anker SD, Ahmed A. Hyperuricaemia, chronic kidney disease, and outcomes in heart failure: potential mechanistic insights from epidemiological data. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:712–720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danaei G, Tavakkoli M, Hernan MA. Bias in observational studies of prevalent users: lessons for comparative effectiveness research from a meta-analysis of statins. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:250–262. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity to hidden bias. In: Rosenbaum PR, editor. Observational Studies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. 105–170. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna W, Seward JB, Iwasaka T, Tsang TS. Incidence and mortality risk of congestive heart failure in atrial fibrillation patients: a community-based study over two decades. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:936–941. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, Love TE, Aronow WS, Adams KF, Jr., Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed MI, White M, Ekundayo OJ, Love TE, Aban I, Liu B, Aronow WS, Ahmed A. A history of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in chronic advanced systolic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2029–2037. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tveit A, Flonaes B, Aaser E, Korneliussen K, Froland G, Gullestad L, Grundtvig M. No impact of atrial fibrillation on mortality risk in optimally treated heart failure patients. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:537–542. doi: 10.1002/clc.20939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gheorghiade M, Hall VB, Jacobsen G, Alam M, Rosman H, Goldstein S. Effects of increasing maintenance dose of digoxin on left ventricular function and neurohormones in patients with chronic heart failure treated with diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Circulation. 1995;92:1801–1807. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Veldhuisen DJ. Low-dose digoxin in patients with heart failure. Less toxic and at least as effective? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:954–956. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Veldhuisen DJ, Man in't Veld AJ, Dunselman PH, Lok DJ, Dohmen HJ, Poortermans JC, Withagen AJ, Pasteuning WH, Brouwer J, Lie KI. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of ibopamine and digoxin in patients with mild to moderate heart failure: results of the Dutch Ibopamine Multicenter Trial (DIMT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1564–1573. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90579-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed A. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in geriatric heart failure: importance of low doses and low serum concentrations. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:323–329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed A, Pitt B, Rahimtoola SH, Waagstein F, White M, Love TE, Braunwald E. Effects of digoxin at low serum concentrations on mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a propensity-matched study of the DIG trial. Int J Cardiol. 2008;123:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed A, Waagstein F, Pitt B, White M, Zannad F, Young JB, Rahimtoola SH. Effectiveness of digoxin in reducing one-year mortality in chronic heart failure in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM. Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2003;289:871–878. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.7.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider MP, Hua TA, Bohm M, Wachtell K, Kjeldsen SE, Schmieder RE. Prevention of atrial fibrillation by Renin-Angiotensin system inhibition a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2299–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goette A, Staack T, Rocken C, Arndt M, Geller JC, Huth C, Ansorge S, Klein HU, Lendeckel U. Increased expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and angiotensin-converting enzyme in human atria during atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1669–1677. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, Hillege HL, Bergsma-Kadijk JA, Cornel JH, Kamp O, Tukkie R, Bosker HA, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van den Berg MP Investigators RI. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Le Huezey JY, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann LS, Smith SC, Jr, Priori SG, Estes NA, III, Ezekowitz MD, Jackman WM, January CT, Page RL, Slotwiner DJ, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Albert N, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task F. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123:e269–e367. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214876d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khand AU, Rankin AC, Martin W, Taylor J, Gemmell I, Cleland JG. Carvedilol alone or in combination with digoxin for the management of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1944–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleland JG, Cullington D. Digoxin: quo vadis? Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:81–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.859322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gheorghiade M, Patel K, Filippatos G, Anker SD, van Veldhuisen DJ, Cleland JG, Metra M, Aban IB, Greene SJ, Adams KF, McMurray JJ, Ahmed A. Effect of oral digoxin in high-risk heart failure patients: a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the DIG trial. Eur J Heart Fail. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft010. Advance Access published Jan 25, 2013, doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hft010 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, Youngman L, Collins R, Marmot M, Peto R. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:341–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]