Abstract

People in conversation tend to accommodate the way they speak. It has been assumed that this tendency to imitate each other's speech patterns serves to increase liking between partners in a conversation. Previous experiments examined the effect of perceived social attractiveness on the tendency to imitate someone else's speech and found that vocal imitation increased when perceived attractiveness was higher. The present experiment extends this research by examining the inverse relationship and examines how overt vocal imitation affects attitudes. Participants listened to sentences spoken by two speakers of a regional accent (Glaswegian) of English. They vocally repeated (speaking in their own accent without imitating) the sentences spoken by a Glaswegian speaker, and subsequently imitated sentences spoken by a second Glaswegian speaker (order counterbalanced across participants). After each repeating or imitation session, participants completed a questionnaire probing the speakers' perceived power, competence, and social attractiveness. Imitating had a positive effect on the perceived social attractiveness of the speaker compared to repeating. These results are interpreted in light of Communication Accommodation Theory.

Keywords: imitation, speech, accent, attitudes, stereotypes, perception

Introduction

It is well-documented that speakers in conversation have a tendency to converge their speech to their conversation partner's pronunciation patterns (Goldinger, 1998; Namy et al., 2002; Shockley et al., 2004; Pardo, 2006; Pardo et al., 2010; Nielsen, 2011), a phenomenon that is also referred to as accommodation or imitation of speech. Imitation of speech has been found for intonation (Goldinger, 1998), clarity (Lakin and Chartrand, 2003), speech rate (Giles et al., 1991) regional accent (Delvaux and Soquet, 2007), and speech style (Kappes et al., 2009). This phenomenon seems fairly robust and happens in conversation (Pardo, 2006) but also as a result of mere exposure to speech (Goldinger, 1998; Delvaux and Soquet, 2007). Imitation of speech has received considerable attention in recent years (see Babel, 2011, for an overview) and studies are beginning to map out underlying mechanisms of this behavior in speech production (Pardo, 2006; Babel, 2011).

Imitative behavior during interactions has been shown to increase affiliation and liking between conversation partners (LaFrance and Broadbent, 1976; Chartrand and Bargh, 1999; Dijksterhuis and Bargh, 2002; Van Baaren et al., 2004; Stel et al., 2010). The results of these experiments generally demonstrate that observers have a tendency to imitate their interaction partner's posture and gestures more if they like her or him more. Conversely, observers like their interaction partners more if these partners imitate the observers' posture and gestures. For instance, Stel et al. evaluated the effect of observers' a priori liking of their interaction partner on these observers' tendency to imitate. They asked participants to watch a silent video displaying an actor playing a manager (the target) talking about his work. The target often played with a pen and rubbed his face. A priori liking was manipulated by providing participants with different information. Participants were before watching the video that the manager was entirely honest or dishonest (depending on the a priori liking condition) about the topic he was talking about in the video. They were then asked to fill in a questionnaire to assess a priori liking of the target. Participants were videotaped while observing the video, with one third of the participants instructed to imitate the target, one third explicitly instructed not to imitate the target, and a one third group of participants did not receive any instructions regarding imitation. It was counted how often the participants rubbed their face or played with their pen. The results showed that a priori liking had a positive effect on imitative behavior; participants who had received positive information about the target rubbed their face and played with their pen more often, both in the instructed imitation and the non-instructed imitation conditions. Interestingly, participants who had not been instructed to imitate and participants who had received negative information still imitated the target. This experiment shows a positive relationship between a priori liking and imitative behavior and also demonstrates that imitation occurs even when participants do not show a priori liking.

Another study (Stel et al., 2008) illustrated that the act of imitating a target also affects how the imitator feels toward the target or, more specifically, goals associated with the target. Here, participants were split into two groups and instructed to watch a video of the target describing a charitable organization. In one condition, the participants were instructed to imitate the facial expressions of the target, while the participants in the second condition were instructed not to mimic the target's facial expressions. Subsequently, participants in both conditions were given a questionnaire about the charitable organization and given the opportunity to donate some money if they wished (this money had been provided beforehand to both groups of participants). The results showed that participants who had been instructed to imitate donated more money, which was interpreted as an indication that the imitators had a more pro-social attitude toward the organization than the non-imitators.

Recent work in experimental phonetics similarly points to a relationship between vocal imitation and liking (Babel, 2011). Babel tested how perceived liking affects vocal imitation in a speech production experiment. Liking of the target speaker was measured through a social attractiveness rating on a scale between 1 and 10. Babel found that participants selectively imitated spectral characteristics of only a subset of vowels. Higher imitation rates were found for the low vowels /ae a/ and lower imitation rates for the vowel /i o u/. Also, there was a trend for attractiveness to affect the extent to which participants imitated the target's vowels: (female) participants were more likely to imitate a speaker's vowels if they rated the speaker as more socially attractive. Babel's results are in line with research in social psychology showing that perception of social characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race) of a person performing an action may result in (imitative) behavior congruent with attitudes associated with those characteristics (Bargh et al., 1996; Chen and Bargh, 1997; Dijksterhuis et al., 2000). For instance, Bargh et al. primed participants with attitudes related to old age and subsequently measured the speed with which they walked down a hallway. Participants who had been primed with the old age stereotype walked slower than those who had not been primed (but see Doyen et al., 2012).

Research in social psychology and experimental phonetics thus converges on the notion that a number of factors (such as social attractiveness) can lead to an increase in imitative behavior. However, what is unclear is whether the opposite relationship also holds true: does imitating someone's speech patterns also affect the perceived social attractiveness of that person? If imitative behavior can be shown to affect such attitudes, then this implies that the link between imitation and liking is bidirectional in speech: liking a person results in more imitation of that person's behavior, and imitative behaviors in themselves lead to increased liking of the imitated person.

A recent study presented positive effects of vocal imitation on speech perception (Adank et al., 2010). Adank et al. asked participants to listen to sentences spoken in an unfamiliar accent in background noise in a pre-test phase and repeat these sentences aloud. Subsequently, participants were split into six groups and either received no training, listened to sentences in the unfamiliar accent without speaking, repeated the accented sentences in their own accent, listened to and transcribed the accented sentences, listened to and imitated the accented sentences, or listened to and imitated the accented sentences without being able to hear their own vocalizations. Post-training measures showed participants who imitated the speaker's accent repeated key words in the sentences in higher levels of background noise than participants who had not imitated the accent. Adank et al. demonstrated that vocal imitation of speech affects speech perception by optimizing comprehension of sentences in background noise. Adank et al. thus showed that vocal imitation may aid comprehension of the linguistic message.

The present study aims to establish whether and how vocal imitation affects social attitudes associated with the speaker of this linguistic message. We examined the effect of vocal imitation on attitudes held by listeners toward speakers of a different regional accent than spoken by the listeners themselves. We chose accented speech, as it has already been shown that people spontaneously imitate aspects of their conversation partner's accent (Delvaux and Soquet, 2007). Furthermore, hearing accented speech automatically invokes accent attitudes associated with speakers of the accent (Giles, 1970; Bishop et al., 2005; Coupland and Bishop, 2007).

Here, participants listened to two speakers and overtly imitated the speech patterns for one of these speakers, while they repeated the speech patterns in their own accent for the other speaker. Using a within-subjects design, participants performed these two tasks in counterbalanced order. In one task, they listened to sentences spoken in a regional accent of British English and subsequently repeated these sentences in their own accent, without imitating the accent (repeating phase). Subsequently, they completed a questionnaire probing attitudes related to the speaker's perceived characteristics, including social attractiveness, power, and competence (Bayard et al., 2001). In the other task, participant listened to a different set of sentences spoken by a different speaker of the same regional accent and they were requested to listen to the sentence and repeat it while imitating it as closely as possible (imitating phase). Next, they completed a questionnaire for the second speaker. Participants were thus required to listen to speech from speakers with a regional accent that was different from their own accent. It was decided to select speakers with regional accent as accented speech automatically invokes attitudes associated with its speakers (Lambert et al., 1960). For instance, speakers of standard accents are perceived as more powerful, competent, and having higher social attractiveness than speakers of a regional accent (Giles, 1970; Bishop et al., 2005; Coupland and Bishop, 2007; Grondelaers et al., 2010). If vocal imitation specifically affects listeners' perceived social attractiveness ratings of speakers with a different regional accent, then it is expected that these attitudes are more positive after the experiment's imitation phase.

Method

Participants

We tested 52 participants (32 female, 20 male), with an average age of 26.0 years [range 18–55 years, standard deviation (SD) 7.9 years]. All were native speakers from England, with no language impairment or neurological/psychiatric diseases, and with good hearing. We did not monitor the regional background from the participants within England. All participants were undergraduate students enrolled at the University of Manchester. All participants stated to be unfamiliar with Scottish accents in general and Glaswegian specifically when questioned about this during the debriefing session following the experiment. None of them had lived in Scotland or had any close contact with Scottish speakers on an everyday basis. They gave written consent and received course credit, or £5 for participating. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Stimulus materials

The stimulus materials were 96 sentences spoken by two male Glaswegian English (GE) speakers who were 20 and 21 years old at the time the recordings were made. The GE recordings were obtained during the recording session described in Adank et al. (2009). For every speaker, recordings were made of 96 sentences (see Appendix 1) from the Harvard sentences corpus (Egan, 1948; IEEE, 1969). The Harvard sentences are phonetically balanced and semantically meaningful and are frequently used in studies testing speech intelligibility (Rogers et al., 2004).

The GE speakers were recorded in a sound-treated room, using an AKG SE300B microphone (AKG Acoustics, Vienna, Austria), attached to an AKG N6-6E preamplifier, on a Tascam DA P1 DAT recorder (Tascam Div., TEAC Corp., Tokyo, Japan), and transferred directly to hard disk using a Kay Elemetrics DSP sonagraph (Kay Elemetrics, Lincoln Park, NJ). All sentences were saved into individual files at 22,050 Hz. Finally, each sound file was peak-normalized and scaled to 70 dB sound pressure level (SPL), using Praat (Boersma and Weenink, 2003).

We selected GE as we expected that it would be perceived as having low social attractiveness, as it was ranked 29 out of 34 accents of English in terms of its social attractiveness and prestige (Coupland and Bishop, 2007). Coupland and Bishop used ratings based on the responses from the 5010 participants in the Voices project from the British Broadcasting Cooperation's (BBC) that ran throughout 2005 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/voices/). Respondents in the Voices project were fairly evenly distributed across the UK, including Wales (5.6%), Scotland (11.%), Northern Ireland, North/Mid England (39.9%), South-East England (29.1%), South-West England (11.5%).

Procedure

All participants completed a repeating and an imitation session. The order of these sessions was counterbalanced across participants to avoid task sequence effects; half of the participants completed the imitation session first followed by the repeating session, while the other half imitated first and repeated next. There were 48 sentences per session.

Instructions for the repeating and imitation sessions were taken from Adank et al. (2010). In the repeating session, participants were instructed to listen to the sentence and then to repeat it in their own accent, namely Standard British English. Participants were explicitly instructed not to imitate the speaker's accent. In the imitation session, the procedure was the same as for the repeating session, but participants were instructed to imitate vocally the precise pronunciation of the sentence. If participants repeated the sentence in their own accent, they were instructed to imitate the accent as they heard it spoken. During the repeating task, the experimenter scored the number of correctly repeated content words (see Appendix 1) to ensure that participants understood the sentences. During imitating, the (phonetically naïve) experimenter judged the effort with which participants imitated the speaker's accent on a scale between 1 (very little effort) and 4 (a great deal of effort). The experimenter was instructed to give a score of 1 if they thought that the participant did not attempt to change their speech at all, give a score of 2 if the participant changed their voice, irrespective of whether this was toward the GE accent, and give scores of 3 or 4 if participants attempted to change their voice and managed to replicate aspects of the GE accent. Participants received no feedback other than the experimenter's reminders to keep imitating (in the imitation sessions) or avoid imitating (in the repeating sessions) as described above.

Each participant was tested individually in a quiet room. First, participants repeated 10 familiarization sentences from a male GE speaker whose recordings were not included in the main experiment. Next, they heard 48 sentences over headphones (Sennheiser HD 25 SP) from one of the GE speakers in the repeating session, and the remaining 48 sentences as spoken by the other GE speaker in the imitation session. We included two speakers as it allowed us to evaluate whether the effect of vocal imitation on accent attitudes is general or speaker-specific. As well as counterbalancing for task order, the order of the speakers was counterbalanced across participants, ensuring that speaker 1 was equally often imitated or repeated as speaker 2. If the effect of imitation is speaker-specific, then effects of imitation on social attractiveness ratings differ between speakers.

After each repeating and imitation session, participants were asked to rate their impression of the speaker on 18 personality and voice traits, using a questionnaire (see Appendix 2), which was adapted from Bayard et al. (2001). Bayard et al. developed this questionnaire to examine accent attitudes of New Zealand participants toward different accents of English (New Zealand, Australia and Northern America). The questionnaire consisted of 22 traits: five were voice quality traits (powerful voice, strong voice, educated voice, pleasant voice, attractive voice), 13 were personality traits (controlling, authoritative, dominant, assertive, reliable, intelligent, competent, hardworking, ambitious, cheerful, friendly, warm, humorous), and four status items (occupation, income, social class, education level). The voice quality items and the personality items consisted of Likert-scale questions, asking participants to rate the extent to which the speaker conformed to the trait, while the four status items were set up as open questions. We included only the personality and voice items in the rating scale to allow for answers on a Likert-scale only. In the experiment, participants rated each trait on a scale between 1 and 4 (1: speaker conforms very much to the trait, 4: speaker does not at all conform to the trait).

Participants completed the questionnaire twice: once after the repeating session and once after the imitation session. They were asked to rate their impressions of each speaker. After the experiment, participants were debriefed. Post-experiment debriefing ensured that participants were unaware of the experimental aims and unfamiliar with the Glaswegian accent. The total duration of the experimental procedure (instructions and informed consent procedure, practice session, repeating session, completing questionnaire for the repeating session, imitating session, completing questionnaire for the imitating session, debriefing) was 45 min.

Results

Attitudes

Participants correctly repeated 94.8% (SD 3.7%) of four target words per sentence in the repeating phase of the experiment, indicating their understanding of the accented sentences. Furthermore, the average score for the effort judgments obtained during the imitation sessions was 2.2 (SD 0.9), indicating that participants overall were judged to make reasonable efforts when imitating the speaker's accent. Next, the 18 traits were grouped into Power, Competence, and Social Attractiveness attitudes. Following Bayard et al. Six traits were classified as Power attitudes (controlling, authoritative, dominant, powerful voice, strong voice, assertive), six as Competence attitudes (reliable, intelligent, competent, hardworking, educated voice, ambitious), and six as Social Attractiveness attitudes (cheerful, friendly, warm, humorous, attractive voice, pleasant voice). Bayard et al. originally grouped the traits “attractive voice” and “pleasant voice” into a separate “Voice Traits” factor but we decided to pool these factors into the Social Attractiveness attitude to equalize the number of traits per attitude and to ensure that each trait included personality as well as voice traits.

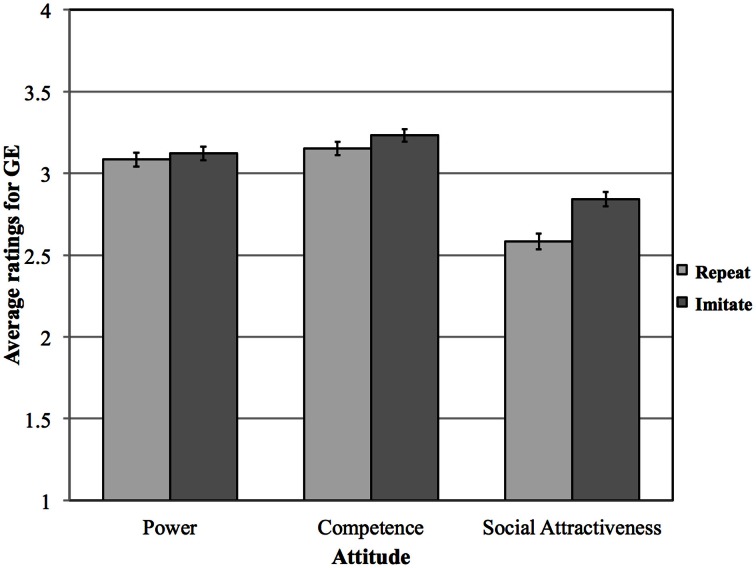

We recoded all rating scores so that low scores became high scores to make data interpretation more intuitive (i.e., higher scores indicate greater conformity). A 2 (Task: Repeat or Imitate) × 3 (Attitude: Power, Competence, Social Attractiveness) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on average rating scores. A first main effect was found for Task [F(1, 48) = 4.775, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.09]. Rating scores were overall higher after imitating (see Figure 1), indicating that participants found the speakers to conform to the attitudes more after imitating. A second main effect was found for Attitude [F(1.488, 75.89) = 21.975, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.3, Huynh-Feldt-corrected for non-sphericity]. Planned t-tests showed that the Social Attractiveness Ratings differed from the Competence (p < 0.001) and the Power ratings but that the Power and Competence ratings did not differ significantly from each other (p = 0.104). Overall, participants judged both the speakers as having better Power and Competences ratings than Social Attractiveness ratings (p < 0.001). The main effects for Task and Attitude were qualified by a significant interaction [F(1.826, 93.126) = 3.371, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.06], indicating that the effects of task affected the three attitudes differently. Post-hoc tests showed that only Social Attractiveness judgments were significantly more positive (p = 0.007), i.e., the speaker was judged to conform more to the trait, after imitation. This indicated that participants rated the speakers as having higher Social Attractiveness after imitation sessions than after repeating sessions.

Figure 1.

Average rating scores for Task: Repeat and Imitate, and Attitude: Power, Competence and Social Attractiveness (error bars represent one standard error of the mean) for both GE speakers.

Finally, we calculated difference scores between ratings of the imitation and the repeating phases and we correlated these difference scores with the individual effort scores obtained during the imitation phase of the experiment. Imitation effort scores did not correlate significantly with Social Attractiveness, Power, or Competence difference scores.

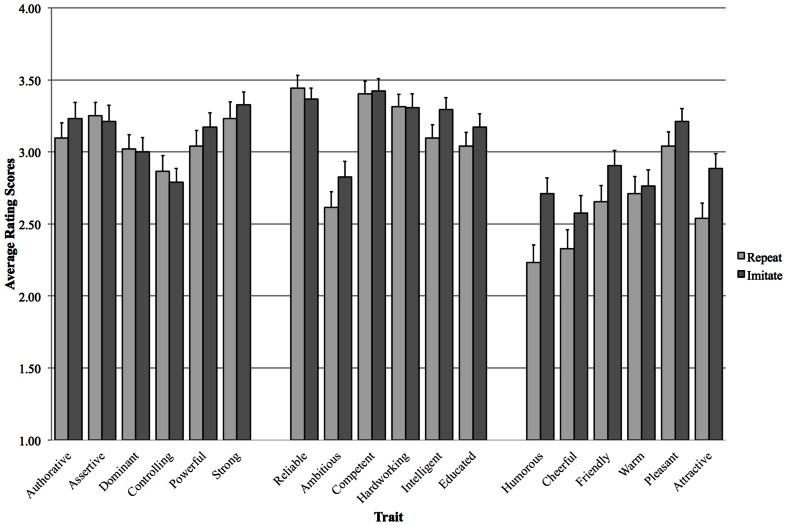

Individual traits

Figure 2 shows the average ratings for the individual traits. We ran planned t-tests between the ratings obtained after imitating and repeating for each trait. The planned t-tests for the Power traits (Authoritative, Dominant, Assertive, Controlling, Powerful voice, Strong voice) showed no significant differences at p < 0.05. No differences were found either for the Competence traits (Reliable, Ambitious, Competent, Intelligent, Hardworking, Educated voice). However, effects were found for three pairs for the Social Attractiveness traits (Humorous, Cheerful, Friendly, Warm, Pleasant voice, Attractive voice). Participants rated the speakers as more humorous after imitating [t(51) = −3.468, p = 0.001], as being more friendly [t(51) = −2.095, p = 0.041] and as having a more attractive voice [t(51) = −3.163, p = 0.003].

Figure 2.

Average rating scores for Task: Repeat and Imitate, for all 18 traits (error bars represent one standard error of the mean) for both GE speakers.

Discussion

We aimed to establish whether vocal imitation of sentences spoken in an unfamiliar accent positively affected social attractiveness ratings associated with the speaker of these sentences. The results confirm our hypothesis, as the ratings of a GE speaker's social attractiveness were more positive after the participant had vocally imitated sentences produced by that speaker. Furthermore, the results showed that the positive effects were found only for the Social Attractiveness ratings and not for the Competence and Power ratings. This pattern in the results allows us to rule out alternative explanations for the effect of imitation, such as increased attention or more effortful processing during the imitation phases of the experiment. It seems unlikely that increased attention or more effortful processing would specifically affect Social Attractiveness, but not Power and Competence ratings. Nevertheless, imitation effort ratings did not correlate with the difference scores for Social Attractiveness, indicating that participants who were judged to exert greater effort did not show a tendency to change their judgments more than those who were judged to have exerted less effort during imitating.

The pattern in the ratings of the three attitudes differed from earlier studies on attitudes on English accents (Bishop et al., 2005; Coupland and Bishop, 2007). We found less positive ratings for Social Attractiveness than for Power and Competence. It is unclear why this is the case, but this could be due to the fact that we tested a relatively select group of participants, namely young undergraduate students from England only, while the listeners in the original BBC project described in Bishop et al. (2005), Coupland and Bishop (2007) originated from all over the UK and included younger and older participant groups and was not restricted to university students alone. Speakers of specific regional varieties of British English may exhibit different patterns in their attitudes toward specific accents.

Finally, the effect of imitation was only found for Social Attractiveness but not for Competence and Power. The effect of imitating on Social Attractiveness was driven by the traits Humorous, Friendly and Attractive Voice. It is possible that the act of imitating another's accent makes the speaker part of participants' social in-group in a way that mere repetition does not. Since people are more positively biased toward people in their in-group than those outside (Brewer, 1979), such in-group favoritism could make the speaker seem more subjectively pleasant while having little effect on power and competence attitudes, which may be less flexible, possibly due to lower susceptibility to generalized attitudes toward unfamiliar accents and speakers of those accents.

Limitations

It should be noted that the effect of imitation on the Social Attractiveness ratings does not necessarily imply that participants' attitudes toward the Glaswegian accent per se have changed. Rather, it may be that the attitudes toward the GE speaker who was imitated have changed. Therefore, imitating the speech of speakers who speak in a relatively unfamiliar way may lead to a more positive appreciation of these speakers' social attractiveness characteristics. However, note that it is not easy to isolate the speaker from the accent. Evaluating to which extent the attitudes toward an individual versus her or his group characteristics (the regional accent) may not be straightforward, as speaker and accent are inherently confounded. A solution would be to run the experiment using a matched-guise speaker (Lambert et al., 1960), i.e., someone who can speak two accents. See for example Evans and Iverson (2004), who used speech from a speaker who spoke Standard Southern British English as well as a Northern British accent. Using a matched-guise speaker would open up possibilities to tease apart the effect of imitating an individual versus imitating an accent.

Also, we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that the positive effect of imitation on the Social Attractiveness judgments is due to the instruction to explicitly not imitate in the repeating task. One way to determine whether the effect on Social Attractiveness is entirely due to imitation and not to the suppression of imitation in the repeating sessions would be to include a control condition in which participants did not receive any explicit instructions regarding imitation. However, such a control condition would not be feasible within the current within-subject design with task order (and speaker) counterbalanced across participants, as was the case in the present study.

Finally, recent studies measuring the effect of attitudes toward a speaker on vocal imitation used acoustic measures (Babel, 2011) or perceptual similarity judgments (Namy et al., 2002; Pardo, 2006; Pardo et al., 2010, 2012) to access the extent to which participants change their speech. For instance, Babel (2011) used measurements of the first two formant center frequencies of the vowels in the words her participants were required to shadow. Pardo et al. (2010) used perceptual measures of phonetic convergence in her conversational design. She asked a group of phonetically naïve listeners to judge the similarity between utterances of two conversation partners recorded before, during and after both took part in a goal-directed task (a map-task in which specific items were name by both partners) in an ABX task. Measures of perceived convergence were then computed by scoring the percent of trials on which a specific item produced after the map-task was judged to be more similar to this item as produced in map task item than it was to the item produced prior to the map task. The present study did not investigate the effect of perceived aspects of the target on vocal imitation, but the effect of vocal imitation on perceived speaker characteristics. However, the study could have benefited from the use of more sophisticated—and objective—measures of vocal imitation performance, such as used in Babel (2011). However, a disadvantage of using acoustic measurements is that data collection and analysis can be extremely time-consuming and that the effect of vocal imitation may not be fully captured using only measures of vowel quality. It would be interesting to pattern-matching methods also used to measure accent similarity, such as the program ACCDIST (Huckvale, 2004) and apply this to individual pairings of the imitator's and the target's sentences. For instance, Pinet et al. (2011) used ACCDIST successfully to establish accent differences between French-English bilinguals and British English. A method such as ACCDIST could be used to provide a more fine grained measure of the extent to which the participants (a) changed their speech between repeating and imitating and (b) to which extent the participant's utterances in the imitation sessions resemble the target speaker's utterances. Such an objective acoustic measure would be an improvement over the effort judgments used in the present experiment. Nevertheless, the current effort judgments from the experimenter in the imitating phases give at the very least an impression of the extent to which the participant attempted to imitate the sentences in the imitation session, but their relevance should not be overstated.

Communication accommodation theory

Phonetic convergence, or the process by which conversation patterns change the acoustic characteristics toward a common target, has been accounted for using Communication Accommodation Theory (Giles et al., 1991; Shepard et al., 2001). Communication Accommodation Theory accounts for phonetic convergence and divergence by exploring the various explanations of processes through which individuals decrease or increase the social distance between themselves and others through verbal and non-verbal behaviors. Phonetic convergence, for instance as demonstrated in Pardo et al. (2012) and Pardo et al. (2010), is seen as one of the mechanisms through which individuals decrease the social distance. This decrease may have the effect of making the interaction flow more smoothly (Pardo et al., 2012). The present results showed that overt changing of an individual's speech toward a target positively affects feeling of sociability toward that target. This process may thus represent another mechanism through which individuals decrease the social distance. This notion is rather speculative, as we did not test individuals in conversation. However, it would be interesting to investigate this possibility in a dyadic design in which conversation partners' mutual liking is manipulated. Liking one's conversation partner could then make one imitate that partner more, in analogy with Stel et al. (2010), and imitating could in turn increase liking more. Furthermore, it could also be the case that the link between imitation and liking also serves to increase social distance. In this scenario, disliking someone may lead conversation partners to imitate less which in turn then leads to even less liking, leading ultimately to an increase of social distance.

Conclusion

In sum, the present research demonstrates that vocal imitating of speech positively alters attitudes about the speaker's perceived Social Attractiveness. These results are in line with previous social psychological studies that found a positive effect of imitation on affiliation for the interaction partner being imitated (LaFrance and Broadbent, 1976), as well as for the individual imitating his or her interaction partner (Stel and Vonk, 2010). Finally, it has already been shown that vocal imitation enhances action perception under ambiguous/noisy listening conditions (Adank et al., 2010), or that vocal imitation improves understanding of the speaker's message. Our results indicate that imitation effects extend to evaluation of the speaker's social characteristics.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Harry Feigen, Elliot Durkan, and Matthew Haigh for their contribution to the work.

Appendix 1

Sentence materials used in the experiment. The 10 familiarization sentences were presented in the order listed across all participants, while the 96 test sentences were randomized across participants.

| Familiarization sentences | Key words | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Plead with the lawyer to fight the lost cause | Plead lawyer lost cause |

| 2 | Pile the coal high in the shed corner | Pile coal shed corner |

| 3 | Be sure to set the lamp firmly in the hole | Sure set lamp hole |

| 4 | We don't like to admit our small faults | Admit our small faults |

| 5 | The pup jerked the leash as he saw a feline shape | Pup leash feline shape |

| 6 | The hail pattered on the burnt brown grass | Hail pattered burnt grass |

| 7 | Open your book to the first page | Open book first page |

| 8 | The long journey home took a year | Long journey took year |

| 9 | Small children came to see him | Small children see him |

| 10 | A severe storm tore down the barn | Severe storm down barn |

| Test sentences | Key words | |

| 1 | Glue the sheet to the dark blue background | Glue sheet dark background |

| 2 | Rice is often served in round bowls | Rice served round bowls |

| 3 | It's easy to tell the depth of a well | Easy tell depth well |

| 4 | A large size in stockings is hard to sell | Large size stockings sell |

| 5 | Four hours of steady work faced us | Four hours steady work |

| 6 | The salt breeze came across from the sea | Salt breeze came sea |

| 7 | The girl at the booth sold fifty bonds | Girl booth fifty bonds |

| 8 | The swan dive was far short of perfect | Swan dive short perfect |

| 9 | Hoist the load to your left shoulder | Hoist load left shoulder |

| 10 | The fish twisted and turned on the bent hook | Fish twisted turned hook |

| 11 | Wipe the grease off his dirty face | Wipe grease dirty face |

| 12 | The stray cat gave birth to kittens | Stray cat birth kittens |

| 13 | The ship was torn apart on the sharp reef | Ship torn apart reef |

| 14 | Sickness kept him home the third week | Sickness kept home week |

| 15 | The crooked maze failed to fool the mouse | Crooked maze fool mouse |

| 16 | The show was a flop from the very start | Show flop very start |

| 17 | March the soldiers past the next hill | March soldiers past hill |

| 18 | The set of china hit the floor with a | China hit floor crash |

| 19 | A tame squirrel makes a nice pet | Tame squirrel nice pet |

| 20 | The clock struck to mark the third period | Clock struck mark period |

| 21 | Cut the pie into large parts | Cut pie large parts |

| 22 | He lay prone and hardly moved a limb | Lay prone moved limb |

| 23 | Bail the boat to stop it from sinking | Bail boat stop sinking |

| 24 | The term ended in late June that year | Term ended June year |

| 25 | The bill was paid every third week | Bill paid third week |

| 26 | The ripe taste of cheese improves with age | Taste cheese improves age |

| 27 | Split the log with a quick, sharp blow | Split log sharp blow |

| 28 | Weave the carpet on the right hand side | Weave carpet hand side |

| 29 | Type out three lists of orders | Type three lists orders |

| 30 | Feel the heat of the weak dying flame | Feel heat dying flame |

| 31 | Mud was splattered on the front of his white shirt | Mud spattered front shirt |

| 32 | The urge to write short stories is rare | Urge short stories rare |

| 33 | The jacket hung on the back of the wide chair | Jacket hung back chair |

| 34 | Torn scraps littered the stone floor | Torn scraps littered floor |

| 35 | Fairy tales should be fun to write | Fairy tales fun write |

| 36 | Acid burns holes in wool cloth | Acid burns holes cloth |

| 37 | Eight miles of woodland burned to waste | Eight miles woodland burned |

| 38 | We admire and love a good cook | Admire love good cook |

| 39 | He carved a head from the round block of marble | Carved head block marble |

| 40 | She has a smart way of wearing clothes | Smart way wearing clothes |

| 41 | Corn cobs can be used to kindle a fire | Corn cobs used kindle |

| 42 | Bring your best compass to the third class | Bring best compass class |

| 43 | The brown house was on fire to the attic | Brown house fire attic |

| 44 | The lure is used to catch trout and flounder | Lure catch trout flounder |

| 45 | The loss of the second ship was hard to take | Loss second hard take |

| 46 | Live wires should be kept covered | Live wires kept covered |

| 47 | The large house had hot water taps | Large house water taps |

| 48 | Write at once or you might forget it | Write once may forget |

| 49 | The lamp shone with a steady green flame | Lamp shone steady flame |

| 50 | Rake the rubbish up and then burn it | Rake rubbish up burn |

| 51 | They are pushed back each time they attack | Pushed back time attack |

| 52 | Some ads serve to cheat buyers | Ads serve cheat buyers |

| 53 | The birch looked stark white and lonesome | Birch looked stark lonesome |

| 54 | Look in the corner to find the tan shirt | Corner find tan shirt |

| 55 | Nine men were hired to dig the ruins | Nine hired dig ruins |

| 56 | The flint sputtered and lit a pine torch | Flint sputtered pine torch |

| 57 | A cloud of dust stung his tender eyes | Cloud dust stung eyes |

| 58 | The old pan was covered with hard fudge | Pan covered hard fudge |

| 59 | Watch the log float in the wide river | Watch log float river |

| 60 | The barrel of beer was a brew of malt | Barrel beer brew malt |

| 61 | The peace league met to discuss their plans | Peace league discuss plans |

| 62 | Boards will warp unless kept dry | Boards warp unless dry |

| 63 | Let it burn, it gives us warmth and comfort | Burn gives warmth comfort |

| 64 | Tack the strip of carpet to the worn floor | Strip carpet worn floor |

| 65 | The man went to the woods to gather sticks | Man woods gather sticks |

| 66 | The dirt piles were lines along the road | Dirt piles lines road |

| 67 | The logs fell and tumbled into the clear stream | Logs fell tumbled stream |

| 68 | Soap can wash most dirt away | Soap wash dirt away |

| 69 | Fake stones shine but cost little | Fake stones shine little |

| 70 | The square peg will settle in the round hole | Square peg settle hole |

| 71 | Heave the line over the port side | Heave line port side |

| 72 | A list of names is carved around the base | List names around base |

| 73 | Grace makes up for lack of beauty | Grace makes lack beauty |

| 74 | Nudge gently but wake her now | Nudge gently wake her |

| 75 | Bottles hold four kinds of rum | Bottles four kinds rum |

| 76 | The man wore a feather in his felt hat | Man feather felt hat |

| 77 | Turn out the lantern which gives us light | Turn lantern gives light |

| 78 | Birth and death mark the limits of life | Birth death mark limits |

| 79 | The chair looked strong but had no bottom | Chair looked strong bottom |

| 80 | Five years he lived with a shaggy dog | Five years lived dog |

| 81 | He offered proof in the form of a large | Offered proof large chart |

| 82 | The three story house was built of stone | Storey house built stone |

| 83 | We like to see clear weather | Like see clear weather |

| 84 | The door was barred, locked, and bolted as well | Door barred locked bolted |

| 85 | Ripe pears are fit for a queen's table | Ripe pears queen's table |

| 86 | The vast space stretched into the far distance | Vast space stretched distance |

| 87 | A rich farm is rare in this sandy waste | Farm rare sandy waste |

| 88 | Hurdle the pit with the aid of a long | Hurdle pit aid pole |

| 89 | The square wooden crate was packed to be shipped | Square wooden crate shipped |

| 90 | Down that road is the way to the grain | Down road grain farmer |

| 91 | A toad and a frog are hard to tell | Toad frog tell apart |

| 92 | A round hole was drilled through the thin board | Round hole drilled board |

| 93 | Prod the old mule with a crooked stick | Prod mule crooked stick |

| 94 | Dull stories make her laugh | Dull stories make laugh |

| 95 | He lent his coat to the tall gaunt stranger | Lent coat tall stranger |

| 96 | The duke left the park in a silver coach | Duke left park coach |

Appendix 2

Questionnaire used after imitation and repeat tasks

Please rate your impressions of the speaker's personality. Circle 1 if you think the speaker's personality does conform very much to the trait, and choose 4 if your think the speaker's personality does not conform at all to the trait.

| Trait | Very | A bit | Not very much | Not at all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reliable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | Ambitious | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | Humorous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | Authoritative | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | Competent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | Cheerful | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | Friendly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | Dominant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | Intelligent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 | Assertive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11 | Controlling | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 | Warm | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | Hardworking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Voice

Please rate your impressions of the speaker's voice. Circle 1 if you think the speaker's voice does conform very much to the trait, and choose 4 if your think the speaker's voice does not conform at all to the trait.

| Trait | Very | A bit | Not very much | Not at all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Powerful | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | Strong | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | Educated | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | Pleasant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | Attractive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Adank P., Evans B. G., Stuart-Smith J., Scott S. K. (2009). Comprehension of familiar and unfamiliar native accents under adverse listening conditions. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 35, 520–529 10.1037/a0013552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adank P., Hagoort P., Bekkering H. (2010). Imitation improves language comprehension. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1903–1909 10.1177/0956797610389192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babel M. (2011). Evidence for phonetic and social selectivity in spontaneous phonetic imitation. J. Phon. 40, 177–189 [Google Scholar]

- Bargh J. A., Chen M., Burrows L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 230–244 10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayard D., Weatherall A., Gallois C., Pittam J. (2001). Pax Americana? Accent attitudinal evaluations in New Zealand, Australia and America. J. Sociolinguist. 5, 22–49 [Google Scholar]

- Bishop H., Coupland N., Garrett P. (2005). Conceptual accent evaluation: thirty years of accent prejudice in the UK. Acta Linguist. Hafniensia Int. J. Linguist. 37, 131–154 [Google Scholar]

- Boersma P., Weenink D. (2003). Praat: doing phonetics by computer. Available online at: http://www.praat.org

- Brewer M. B. (1979). Ingroup bias in the minimal group situation: a cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychol. Bull. 86, 307–324 [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand T. L., Bargh J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: the perception-behaviour link and social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 893–910 10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Bargh J. A. (1997). Nonconscious behavioral confirmation processes: the self-fulfilling consequences of automatic stereotype activation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 541–560 [Google Scholar]

- Coupland J., Bishop H. (2007). Ideologised values for British accents. J. Sociolinguist. 11, 74–93 [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux V., Soquet A. (2007). The influence of ambient speech on adult speech productions through unintentional imitation. Phonetica 64, 145–173 10.1159/0000107914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijksterhuis A., Bargh J., Miedema J. (2000). Of men and mackerels: attention and automatic behavior, in Subjective Experience in Social Cognition and Behavior, eds Bless H., Forgas J. P. (Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; ), 36–61 [Google Scholar]

- Dijksterhuis A., Bargh J. A. (2002). The perception-behavior expressway: automatic effects of social perception on social behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 300, 1–40 [Google Scholar]

- Doyen S., Klein O., Pichon C., Cleeremans A. (2012). Behavioral priming: it's all in the mind, but whose mind? PLoS ONE 7, 1–7 10.1371/journal.pone.0029081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan J. P. (1948). Articulation testing methods. Laryngoscope 58, 955–991 10.1288/00005537-194809000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B. G., Iverson P. (2004). Vowel normalization for accent: an investigation of best exemplar locations in northern and southern British English sentences. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115, 352–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles H. (1970). Evaluative reactions to accents. Educ. Rev. 22, 211–227 [Google Scholar]

- Giles H., Coupland J., Coupland N. (1991). Contexts of Accommodation: Developments in Applied Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger S. D. (1998). Echoes of echoes? An episodic theory of lexical access. Psychol. Rev. 105, 251–279 10.1037/0033-295X.105.2.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondelaers S., Van Hout R., Steegs M. (2010). Evaluating regional accent variation in Standard Dutch. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 29, 101–116 [Google Scholar]

- Huckvale M. (2004). ACCDIST: a metric for comparing speakers' accents, in Proceedings of ICSLP, eds Kim S. H., Young D. H. (Jeju: ). [Google Scholar]

- IEEE. (1969). IEEE recommended practice for speech quality measurements. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. AU-17, 225–246 [Google Scholar]

- Kappes J., Baumgaertner A., Peschke C., Ziegler W. (2009). Unintended imitation in nonword repetition. Brain Lang. 111, 140–151 10.1016/j.bandl.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance M., Broadbent M. (1976). Group rapport: posture sharing as a nonverbal indicator. Group Organ. Stud. 1, 328–333 [Google Scholar]

- Lakin J. L., Chartrand T. L. (2003). Using non-conscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol. Sci. 14, 334–339 10.1111/1467-9280.14481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert W. E., Hodgson R. C., Gardner R. C., Fillenbaum S. (1960). Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 60, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy L. L., Nygaard L. C., Sauerteig D. (2002). Gender differences in vocal accommodation: the role of perception. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 21, 422–432 [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K. (2011). Specificity and abstractness of VOT imitation. J. Phon. 39, 132–142 [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J. S. (2006). On phonetic convergence during conversational interaction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 2382–2393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J. S., Gibbons R., Suppes R., Krauss R. M. (2012). Phonetic convergence in college roommates. J. Phon. 40, 190–197 [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J. S., Jay I. C., Krauss R. M. (2010). Conversational role influences speech imitation. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 72, 2254–2264 10.3758/APP.72.8.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinet M., Iverson P., Huckvale M. (2011). Second-language experience and speech-in-noise recognition: 1 effects of talker-listener accent similarity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130, 1653–1662 10.1121/1.3613698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. L., Dalby J., Nishi K. (2004). Effects of noise and proficiency level on intelligibility of Chinese-accented English. Lang. Speech 47, 139–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard C. A., Giles H., Le Poire B. A. (2001). Communication accommodation theory, in The New Handbook of Language and Social Psychology, eds Robinson W. P., Giles H. (Chicester: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.). 33–56 [Google Scholar]

- Shockley K., Sabadini L., Fowler C. A. (2004). Imitation in shadowing words. Percept. Psychophys. 66, 422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel M., Van Baaren R. B., Blascovich J., Van Dijk E., McCall C., Pollman M. M. H., et al. (2010). Effects of a priori liking on the elicitation of mimicry. Exp. Psychol. 57, 412–418 10.1027/1618-3169/a000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel M., Van Baaren R. B., Vonk R. (2008). Effects of mimicking: acting prosocially by being emotionally moved. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 965–976 [Google Scholar]

- Stel M., Vonk R. (2010). Mimicry in social interaction: benefits for mimickers, mimickees, and their interaction. Br. J. Psychol. 101, 311–323 10.1348/000712609X465424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Baaren R. B., Holland R. W., Kawakami K., Van Knippenberg A. (2004). Mimicry and pro-social behavior. Psychol. Sci. 15, 71–74 10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]