Abstract

Gene therapeutic strategies have shown promise in treating vascular disease. However, their translation into clinical use requires pharmaceutical carriers enabling effective, site-specific delivery as well as providing sustained transgene expression in blood vessels. While replication-deficient adenovirus (Ad) offers several important advantages as a vector for vascular gene therapy, its clinical applicability is limited by rapid inactivation, suboptimal transduction efficiency in vascular cells, and serious systemic adverse effects. We hypothesized that novel zinc oleate-based magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) loaded with Ad would enable effective arterial cell transduction by shifting vector processing to an alternative pathway, protect Ad from inactivation by neutralizing factors, and allow site-specific gene transfer to arteries treated with stent angioplasty using a 2-source magnetic guidance strategy. Ad-loaded MNPs effectively transduced cultured endothelial and smooth muscle cells under magnetic conditions compared to controls and retained capacity for gene transfer after exposure to neutralizing antibodies and lithium iodide, a lytic agent causing disruption of free Ad. Localized arterial gene expression significantly stronger than in control animal groups was demonstrated after magnetically guided MNP delivery in a rat stenting model 2 and 9 d post-treatment, confirming feasibility of using Ad-loaded MNPs to achieve site-specific transduction in stented blood vessels. In conclusion, Ad-loaded MNPs formed by controlled precipitation of zinc oleate represent a novel delivery system, well-suited for efficient, magnetically targeted vascular gene transfer.—Chorny, M., Fishbein, I., Tengood, J. E., Adamo, R. F., Alferiev, I. S., Levy, R. J. Site-specific gene delivery to stented arteries using magnetically guided zinc oleate-based nanoparticles loaded with adenoviral vectors.

Keywords: physical targeting, in-stent restenosis, rat model

Achieving efficient and specific gene delivery to target cells and organs is a major challenge in successful translation of gene therapeutic strategies into clinical use. Adenoviruses (Ads) combining high-transgene capacity, ability to transduce both dividing and quiescent cells, early onset of transgene expression, and a low risk of insertional mutagenesis due to their nonintegrated state in the host cell, remain leading candidate vectors for development as a treatment modality for a wide range of clinical applications (1). The advantages of Ad as a gene vector are particularly relevant for conditions characterized by a defined critical period at which a therapeutic intervention should be aimed in order to prevent the progression of a disease, thus obviating the need for a permanent genetic cell modification (2). However, the therapeutic use of Ad is limited by a number of factors, including an acute immune response elicited through action on nontarget cells (3), susceptibility to inactivation, and suboptimal efficacy in tissues exhibiting low permissivity to the vector (4). While progress has been made in overcoming some of these issues by protecting Ad from activity loss in the presence of neutralizing chemical and immunological factors (5, 6), physically stabilizing the vector (7, 8), or improving its pharmacologic selectivity and reducing toxicity by shifting its distribution toward therapeutically relevant targets (9, 10), developing a single approach both potentially viable clinically and effective in addressing these limitations remains a challenge.

The present studies were designed to explore magnetically targeted delivery of Ad formulated in biocompatible, zinc oleate-based magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) as a means to achieve high levels of transgene expression in a site-specific manner in blood vessels treated by stent angioplasty. Arterial reocclusion after stent implantation (i.e., in-stent restenosis), and especially its variant developing in patients treated with drug-eluting stents, has been recognized as a major problem in the field of cardiovascular therapy due to the progressively increasing number of occurrences and the virtual lack of effective treatment modalities (11, 12). Stent-targeted delivery of gene vectors to achieve sustained expression of therapeutic transgenes at the site of arterial injury can potentially provide a safe and effective treatment strategy. Notably, the transient temporal pattern of the underlying processes in the pathophysiology of restenosis makes Ad with its characteristic mode of gene expression particularly well-suited for this therapeutic application (2, 13). However, successful implementation of Ad-based antirestenotic gene therapy will require providing the vector in a protected form, overcoming the low permissivity of vascular cells to adenoviral transduction, and achieving therapeutic levels of transgene expression in injured arteries without systemic exposure to potentially toxic vector doses. With these requirements in mind, zinc oleate-based MNPs loaded with Ad [MNP(Ad)s] were investigated in the present studies as a carrier for magnetically targeted gene delivery to stented arteries. Ad, coincorporated in the particles with superparamagnetic nanocrystalline magnetite using mild aqueous formulation conditions, was hypothesized to retain functionality while being protected from inactivation by the particle matrix composed of the highly hydrophobic zinc oleate complex (See scheme in Fig. 1A). As part of the formulation characterization experiments, the effectiveness of magnetically driven MNP(Ad)-mediated gene transfer was evaluated as an alternative to the Coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR)-mediated pathway relatively inefficient in vascular cells (4). Finally, a uniform field-based, 2-source magnetic guidance approach recently shown effective by our group for carotid artery targeting of small-molecule therapeutics and cells (14, 15) was applied herein to achieve targeted gene delivery to stented rat carotid arteries, and the tissue distribution and local arterial levels of MNP(Ad)-mediated transgene expression were examined in comparison to nonmagnetic treatment conditions and free Ad.

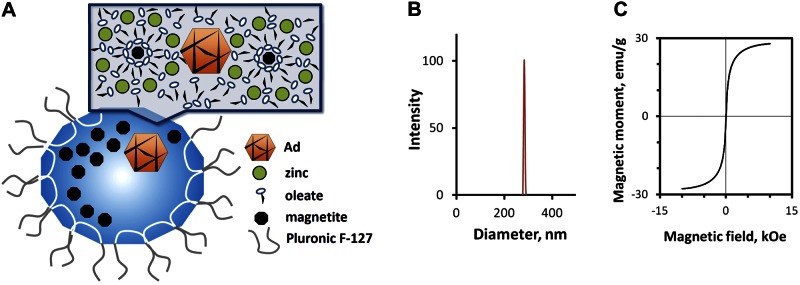

Figure 1.

A) Scheme showing structure and composition of zinc oleate-based MNPs impregnated with Ad. B, C) Size distribution (B) and magnetization curve (C) of Ad-loaded MNPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nanoparticle preparation and characterization

Type 5 first-generation Ads under the control of the CMV promoter used in this study were provided by the Gene Vector Core Facility of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA, USA; firefly luciferase and enhanced GFP) and the Gene Transfer Vector Core of the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA, USA; iNOS).

MNP(Ad)s were formulated with zinc oleate as the matrix-forming material using a 2-step process. Magnetite was first obtained by adding 2.5 ml of an ethanolic solution containing 170 mg ferric chloride hexahydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 62.5 mg of ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (Acros Organics/Fisher Scientific USA, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) to 5 ml of an aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (5 N). The precipitate was heated to 90°C with shaking for 1 min, magnetically separated, and resuspended in 5 ml of an aqueous solution containing 225 mg of sodium oleate (Sigma-Aldrich). To obtain colloidal dispersion of oleate-stabilized magnetite, the contents were treated with 2 heating/sonication cycles (90°C, 5 min/bath sonication, 5 min). The colloidal dispersion was passed sequentially through a 1.0-μm glass fiber prefilter (Millipore Billerica, MA, USA) and a sterile 0.45-μm glass/acetate filter (GE Water & Process Technologies, Trevose, PA, USA) into a presterilized vial. Sterile-filtered solutions were used throughout the remainder of the procedure in order to maintain aseptic conditions. In the next step, 200 μl of an aqueous solution of Pluronic F-127 (10%) and 1011 Ad particles diluted to 100 μl with water were added to 0.75 ml of the magnetite dispersion, and nanoparticles were formed by zinc oleate precipitation with 0.75 ml of a 0.1 M zinc chloride solution in water added dropwise with shaking. The particles were placed on an orbital shaker for 15 min at 4°C, then washed by 2 magnetic decantation/resuspension cycles on ice and reconstituted in an ice-cold 10% solution of trehalose. The volume was adjusted to 0.75 ml, and the MNP(Ad)s were portioned into aliquots and kept frozen at −80°C. For lyophilization studies, trehalose was replaced with a mixture of Pluronic F-127 and glucose (1 and 5%, respectively) in ice-cold water. MNP(Ad)s were frozen overnight at −80°C, lyophilized over 24 h, stored at −80°C, and reconstituted in deionized water (Barnstead Nanopure; Thermo Scientific, Dubuque, IA, USA) before use. Blank MNPs were obtained as above without adding Ad. Calcium oleate-based MNP(Ad)s were formed using calcium chloride instead of zinc chloride during the oleate precipitation step.

Particle size measurements were performed by dynamic light scattering. Hysteresis loops of MNPs were obtained using an alternating gradient magnetometer (Princeton Measurements Corp., Princeton, NJ, USA). Magnetite content was determined spectrophotometrically against a suitable calibration curve (λ=360 nm) in MNP samples dissolved in hydrochloric acid (5 N) by heating to 60°C for 20 min.

Cell culture studies

Rat aortic smooth muscle cells (A10 line) and bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were seeded at 104 cells/well on 96-well plates. For magnetically enhanced transduction, the plates were positioned on a 96-well magnetic separator with an average field gradient of 32.5 T/m (LifeSep 96F; Dexter Magnetic Technologies, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA). Cells on plates unexposed to the high-gradient field were used as a control. The cells were treated for 15 min (unless otherwise stated) with MNP(Ad)s or free Ad diluted in DMEM containing 10% FBS, then washed twice and incubated with fresh FBS-supplemented DMEM. Reporter gene expression was assayed in live cells at predetermined time points using fluorimetry (λex/λem=485 nm/535 nm) and luminometry for enhanced GFP and luciferase, respectively. For luminometric measurements the cell medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 50 μg/ml d-luciferin potassium salt (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the plate was read using an IVIS Spectrum optical imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA). NO production by BAECs was determined by measuring nitrite concentration in cell culture medium 3 d post-treatment using the Griess assay (16). Cell viability was measured using the Alamar Blue fluorimetric assay (17) using untreated cells as a reference.

To determine the protective effect of MNPs against Ad disruption by lithium iodide, MNP(GFPAd)s or free GFPAd were incubated with aqueous solutions of lithium iodide at 0.8–5.0% concentrations. Incubation without added lithium iodide was used in control experiments. After 10 min of incubation at 37°C, MNP(GFPAd)s and free GFPAd were diluted 1:30 with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and applied to BAECs for 60 min at a dose of 3 × 108 Ad/well. The cells were washed twice and incubated with FBS-supplemented DMEM. Reporter expression was measured in live cells fluorimetrically 72 h post-treatment after replacing the medium with PBS, and presented as percentage gene transfer recovery vs. controls unexposed to lithium iodide.

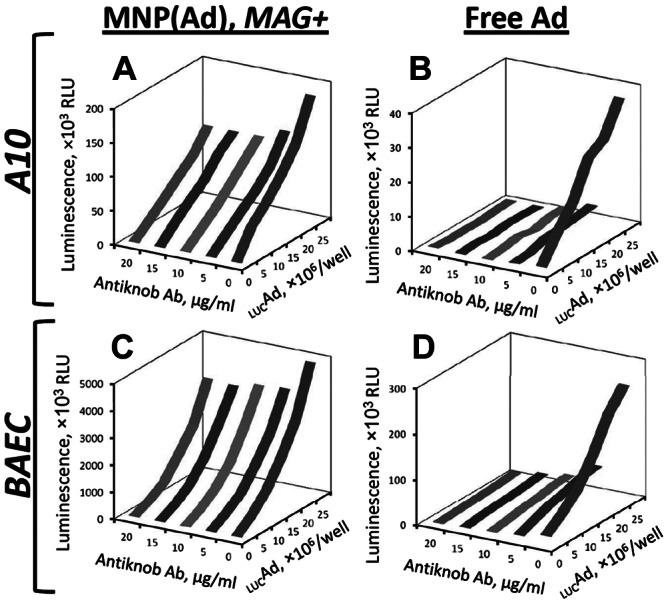

The comparative effect of inhibiting Ad-CAR interaction with a knob-specific antibody (mouse anti-knob IgG, Selective Genetics, San Diego, CA) on the gene transfer capacity of nanoparticles vs. free vector was examined using MNP(LUCAd)s and LUCAd incubated in a series of doses (0–2.5×106 Ad/well) with antibody dilutions in the range of 0–20 μg/ml for 10 min at room temperature, and applied for 15 min or 4 h, respectively, to A10 cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were then washed twice and incubated with fresh FBS-supplemented DMEM, and the reporter expression was assayed 2 d post-treatment as above.

In vivo targeting and biodistribution studies

Animal studies were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Under general anesthesia the left common carotids of male Sprague–Dawley rats (450–500 g) were injured by 3 passages of a Fogarty catheter introduced through an incision made in the left external carotid artery, and a 304-grade stainless steel multilink stent (Laserage Technology Corp., Waukegan, IL, USA) was deployed using an angioplasty balloon catheter (NuMED, Inc., Denton, TX, USA). After stent implantation, a delivery catheter was introduced into the aortic arch, paired electromagnets generating a uniform magnetic field of 1.2 kOe were positioned at a distance of 40 mm at both sides of the animal, and a dose of MNP(LUCAd)s corresponding to 2.5 × 109 Ad particles in 500 μl of isotonic glucose solution (5%) was instilled over 1 min. The magnetic field was maintained for an additional 5 min, the catheter was removed, and the external carotid artery was tied off. Additional animals in the nonmagnetic control group (n=10) and free vector group (n=8) were treated as above with equivalent doses of MNP(LUCAd)s and LUCAd, respectively, without the exposure to the magnetic field. Luciferase expression in the stented arteries was imaged and quantified 2 and 9 d post-treatment using an IVIS Spectrum optical imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) as described elsewhere (18).

The biodistribution of reporter gene expression was examined in animals treated with MNP(LUCAd)s with or without the magnetic field exposure (n=3). Stent implantation and delivery were performed as above. Stented arteries were excised, and the stents were carefully removed 2 d post-treatment. Treated arteries, equally sized segments of the contralateral carotid arteries, and organ tissue samples, including liver, spleen, and lung, were collected, weighed, and homogenized using a bullet blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY, USA) for 15 min at 4°C, and their luminescent signals were read after adding luciferin as described above.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data are expressed as means ± sd except where otherwise stated. In vitro gene expression results were examined by regression analysis. In vivo data were tested by Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA with Dunn's post hoc analysis. Differences were termed significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Formulation of Ad-loaded MNPs

Zinc oleate-based MNP(Ad)s were obtained using a controlled precipitation approach with a narrow size distribution and an average size of 280 ± 10 nm (Fig. 1B). In agreement with their high magnetite loading (32.9% by weight), the particles showed strong magnetic responsiveness (magnetic moments of 19.3±0.5 and 28.5±1.0 emu/g at magnetic field intensities of 1.2 and 10 kOe, respectively; Fig. 1C). The high magnetization of the particles measured at 1.2 kOe and corresponding to 68% of the saturation value is noteworthy, as this field strength is within the range that can be readily applied in the clinical setting (19, 20) and was used for investigation of in vivo stent targeting in this study. The inclusion of magnetite as nanocrystals dispersed in the particle matrix provided MNP(Ad)s with superparamagnetic properties, as evidenced by the relative magnetic remanence equaling 1.19 ± 0.01% of the magnetic moment at saturation. Notably, after lyophilization, MNP(Ad)s retained to a significant extent their capacity for vascular cell transduction [46.8±1.6% transduction efficiency compared to freshly made MNP(Ad)s; see Supplemental Fig. S1] and the narrow size distribution in the submicronial range (average size of 299±13 nm after storage for 2 mo at −80°C).

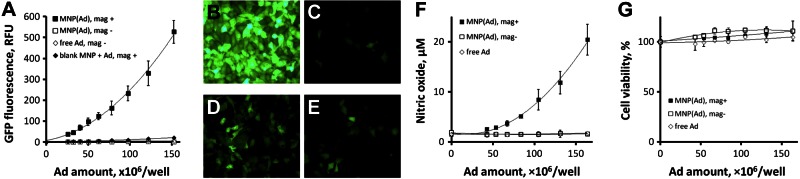

MNP(Ad)-mediated gene transfer efficiency in cell culture

Specific transduction efficiency of magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s vs. nonmagnetic control and free Ad was determined from the respective regression curve slopes of reporter gene expression plotted against the vector dose range (0–1.5×108 Ad/well). The ratio between the specific transduction efficiencies of magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s and free Ad in cultured BAECs measured 24 h post-treatment was 103 ± 11 (P≪0.001; Fig. 2A, B vs. E) and increased to 122 ± 8 by the 72 h time point. In contrast, the transduction levels observed with MNP(Ad)s applied to cells without the magnetic exposure did not exceed those achievable with Ad alone (Fig. 2A, C vs. E). Notably, although cell treatment with free Ad applied in combination with blank MNPs under magnetic conditions resulted in a detectable increase in transduction levels, the respective difference in transgene expression compared to Ad alone was 43-fold lower than that observed with magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s (P≪0.001; Fig. 2A, B vs. D), providing evidence that Ad encapsulation in the particles is essential for achieving efficient magnetically driven gene transfer. A comparison of GFP expression and nitric oxide (NO) production by BAEC treated with MNP formulations loaded with GFPAd and Ad encoding inducible NO synthase (iNOSAd), respectively, reveals similar patterns with respect to MNP dose and magnetic exposure (Fig. 2A, F). The NO amount produced by cells magnetically treated with MNP(iNOSAd)s at a dose of 1.6 × 108 Ad/well was 12.2 ± 1.9-fold higher than the baseline levels of NO determined in untreated cells (Fig. 2F), and this ratio was further increased to 23.2 ± 0.2 at an MNP(Ad) dose corresponding to 2.6 × 108 Ad/well without causing cell toxicity (Supplemental Fig. S2A, C). In comparison, NO amounts produced by cells treated with free iNOSAd or with MNP(iNOSAd)s in absence of magnetic exposure were not significantly different from those observed with untreated cells following the standard treatment period of 15 min. Notably, extending the treatment period from 15 min to 2 h caused only a small relative increase in NO production by cells treated with MNP(iNOSAd)s under magnetic conditions (38.6±0.3 and 47.2±0.5 μM, respectively, at 2.6×108 Ad/well) compared to a 4.8-fold increase from near-baseline NO levels after equally extended exposure to free iNOSAd (1.9±0.0 and 9.1±2.0 μM, respectively, at 2.6×108 Ad/well, Supplemental Fig. S2A vs. B), which suggests that magnetically facilitated cell uptake and processing of Ad incorporated in MNPs occur considerably faster than those of free Ad, favoring strongly increased transduction efficiency with the former, which is particularly prominent at shorter exposure times.

Figure 2.

Magnetically guided transduction with MNP(Ad)s. A–D) BAECs were treated with MNPs formulated with GFPAd in the presence of a high-gradient magnetic field, as described in the text, and reporter expression was measured fluorimetrically (A) and observed by fluorescent microscopy (B) in comparison to controls, including MNP(Ad)s applied under nonmagnetic conditions (C), combination of blank MNPs and free Ad applied with the high gradient field (D), and free Ad (E). Original view: ×200. F) Production of NO by BAECs treated magnetically with MNPs loaded with iNOS-encoding Ad was determined by the Griess assay 3 d post-treatment in comparison with nonmagnetic conditions and free Ad. G) Cell viability was measured using the Alamar Blue (resazurin/resorufin) assay. See Supplemental Fig. S2 for NO production by BAECs exposed to an extended dose range of MNP(iNOSAd)s and for comparison between 15 min and 2 h incubation periods.

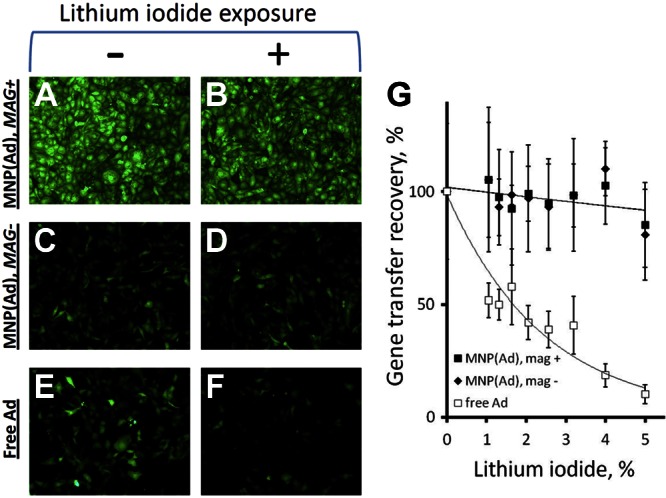

Vector protection and CAR-uncoupled transduction of vascular cells using MNP(Ad)s

The ability of zinc oleate-based MNPs to protect encapsulated Ad was investigated by exposing the formulation to lithium iodide, a model small-molecule lytic agent previously shown to cause physical disruption of the viral capsid and inactivation of the vector (21). Exposure to lithium iodide effectively inactivated free Ad (P≪0.001;, Fig. 3E–G), with the transduction capacity reduced by 90 ± 4% after a 10-min incubation with its 5% solution. Contrastingly, MNP(Ad)s retained their gene transfer capacity, exhibiting no significant decline in cell transduction over the studied range of lithium iodide concentrations (Fig. 3A–D, G).

Figure 3.

Protective effect of encapsulation in MNPs against Ad inactivation by treatment with lithium iodide. MNP(GFPAd)s and free GFPAd were exposed to a range of lithium iodide concentrations and applied to BAECs as described in Materials and Methods. Reporter expression mediated by MNP(GFPAd)s applied to cells with (A, B) or without (C, D) the high-gradient field and by free GFPAd (E, F) was observed in comparison to controls unexposed to lithium iodide (B, D, F vs. A, C, E) by fluorescent microscopy and also assayed fluorimetrically as a function of lithium iodide concentration (G) 3 d post-treatment. Original view: ×100.

One of the primary goals of this study was to develop a strategy enabling site-specific gene transfer to cells of the injured arterial wall, which requires redirecting transduction from the CAR-dependent route, both relatively ineffective in vascular cells and promiscuous in its tropism (4). Hence, a set of experiments was designed to test the hypothesis that, in contrast to free vector, the magnetically enhanced gene transfer with MNP(Ad)s occurs via an alternative pathway uncoupled from the Ad-CAR interaction. This hypothesis was examined by measuring the effect of preexposure to a knob-specific IgG blocking the interaction of the viral knob protein with CAR (18) on gene transfer mediated by magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s vs. free Ad. Due to the differences in respective gene transfer efficiencies observed with magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s and free vector, cell incubation with Ad was extended to 4 h to enable accurate reporter signal measurements, while the 15-min exposure period was kept for MNP(Ad)s applied under magnetic conditions as in previous experiments. While the magnetically driven transduction with MNP(Ad)s was inhibited to a relatively small extent by pretreatment with anti-knob IgG, a profound inhibition of gene transfer mediated by free Ad was observed (Fig. 4B, D vs. A, C) with a >20-fold reduction in gene transfer in both BAECs and A10 cells at 20 μg/ml anti-knob IgG (P≪0.001). These results suggest that Ad encapsulation in MNPs diverts the cellular processing of the vector to an alternative mechanism effectively functioning in the absence of the Ad-CAR interaction, consistent with the shift to a CAR-independent transduction pathway previously observed with particle-associated Ad (22, 23). Notably, this alternative pathway allows rapid processing of MNP-incorporated vector in amounts considerably increased by applying the magnetic treatment conditions. This finding is in agreement with the rapid kinetics of magnetically enhanced internalization suggested by the comparison of the NO production levels by BAECs after 15 vs. 120 min of magnetic exposure to MNP(iNOSAd)s (Supplemental Fig. S2A, B).

Figure 4.

Effect of inhibiting Ad-CAR interaction by anti-knob IgG on MNP(Ad)-mediated (A, C) and free Ad-mediated gene transfer (B, D) in A10 cells (A, B) and BAECs (C, D) as a function of the antibody concentration and vector dose. Luciferase reporter expression was determined after 2 d by assaying cell luminescence, as described in Materials and Methods.

Magnetically guided vascular gene delivery with MNP(Ad)s in the rat model of stent angioplasty

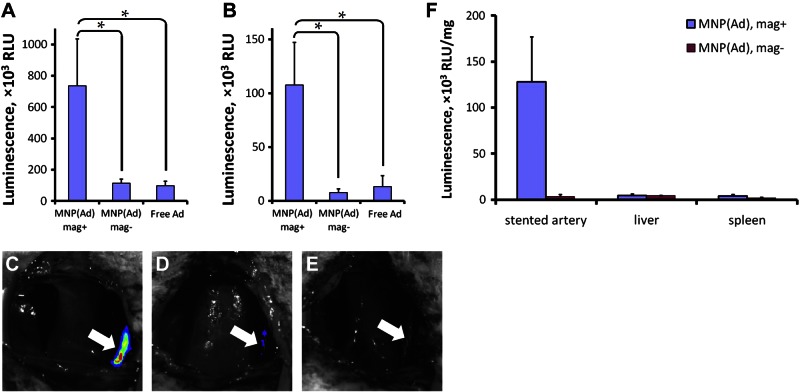

The efficiency of stent-targeted gene transfer using magnetically guided MNP(Ad)s was investigated in the rat carotid model of stent angioplasty in comparison with nonmagnetic delivery and free Ad controls. A significantly stronger reporter expression was determined in the injured arteries by bioluminescent imaging 2 d after magnetic treatment with MNP(LUCAd)s compared to both controls (P<0.001; Fig. 5A, C vs. D, E). The magnetically guided gene transfer with MNP(Ad)s was spatially confined to the stented arterial segment consistent with magnetic force-driven particle accumulation in the vicinity of stent struts (Fig. 5C). While the reporter expression was found to decrease in all animal groups by d 9 post-treatment due to the transient character of transduction mediated by first-generation Ad (24), the expression levels remained significantly higher in the magnetically treated animals in comparison to those in the control groups [14- and 8-fold compared to nonmagnetic MNP(Ad) delivery and free Ad, respectively; P=0.006, Fig. 5B]. The in vivo distribution of transgene expression 2 d after stent-targeted delivery of MNP(Ad)s was compared to that in the nonmagnetic control group by analyzing the reporter enzymatic activity in homogenized tissues. The transgene expression in stented arteries treated magnetically with MNP(Ad)s was found to be 38-fold higher than that determined in the nonmagnetic control animals (Fig. 5F), suggesting that the direct reporter assay, while qualitatively in agreement with the results of bioluminescent imaging, may be a more sensitive tool for quantifying differences in gene transfer efficiencies between the animal groups. Gene transfer in magnetically treated animals was achieved with a high target specificity, as evidenced by the tissue weight-normalized reporter expression levels in stented arteries being 28 ± 11 and 31 ± 12 times stronger than the average transgene expression levels determined in the liver and spleen tissues, respectively. Contrastingly, the ratios of transgene expression in stented arteries to those in the liver and spleen were 0.8 ± 0.5 and 1.9 ± 1.4 in the nonmagnetic control group (Fig. 5F). Notably, the luciferase activity in the lungs and contralateral arteries was 3400 and 447 times lower, respectively, than that measured in magnetically treated arteries, and was comparable between the two animal groups.

Figure 5.

Two-source magnetic targeting of MNP(Ad)s to stented arteries. A, B) Local transgene expression mediated by MNP(LUCAd)s targeted to 304-grade stainless steel stents through exposure to a uniform magnetizing field (1200 G) was determined by live animal bioluminescent imaging 2 d (A) and 9 d post-treatment (B) in comparison to animals treated with MNP(LUCAd)s using nonmagnetic conditions and with free LUCAd. *P < 0.05. C–E) Note the site-specific pattern of the reporter gene expression confined to the stented arterial segment 2 d post-treatment after magnetically targeted delivery of MNP(LUCAd)s (C) in comparison to nonmagnetic delivery (D) and free Ad controls (E). Arrows indicate stent implantation sites. F) Tissue distribution of reporter expression in magnetically vs. nonmagnetically treated animals was measured luminometrically in homogenized tissue samples 2 d post-treatment. Data are presented as means ± se.

DISCUSSION

While the use of Ad for gene delivery offers a number of important potential advantages making it an attractive vector for therapeutic applications requiring high levels of transgene expression in the absence of permanent genetic cell modification (25), the immunogenic toxicity resulting from the action of Ad on nontarget cells and tissues remains the primary factor limiting its clinical use. This limitation can potentially be addressed by developing strategies enabling site-specific delivery and confining the action of Ad to its therapeutic target. A considerable research effort is directed today toward improving biodistribution of Ad via detargeting it from its native receptor and providing it with tropism to alternative molecular targets (10). The vast part of this effort focuses on modifying the virion capsid using chemical and/or genetic strategies. While these approaches have shown promise, detargeting/retargeting of Ad may require combining multiple genetic and/or chemical modifications (10, 26) and can still be ineffective at overcoming physical and biological barriers to achieving therapeutic levels of transgene expression at the target site (27).

The present study evaluated the feasibility of a novel magnetically guided Ad delivery strategy using zinc oleate-based MNP carriers. The MNP formulation developed and characterized in these studies has several properties essential for its effective use for Ad-mediated vascular gene therapy: the encapsulation of functional Ad is achieved using mild aqueous conditions, and the MNP-encapsulated vector remains protected from inactivation both by chemical factors causing disruption of the viral capsid and by neutralizing antibodies; Ad-loaded MNPs exhibit CAR-detargeted cell entry and processing, which is particularly important for gene transfer to arterial tissue, as vascular cells normally express relatively low levels of CAR (4); and the magnetic responsiveness of the carrier enables the use of physical guidance that can be applied effectively for targeted delivery to blood vessels as part of the stent angioplasty procedure (28, 29).

The novel MNP(Ad) formulation approach is based on controlled precipitation of oleate in the form of its water-insoluble zinc salt in presence of nanocrystalline iron oxide, Ad, and a biocompatible surfactant, and provides colloidally stabilized, magnetically responsive particles without the use of organic solvents or mechanical energy that can potentially affect the integrity and activity of the vector. Interestingly, a simple method for obtaining a pharmaceutical grade “oleate of zinc” by precipitation carried out under mild, solventless conditions was described in a paper dating back to 1890 (30). In the present study, a modification of this spontaneous process was applied to form MNPs with a narrow size distribution that, under magnetic guidance, can mediate efficient adenoviral gene transfer both in vitro and in vivo. While the capacity for magnetic targeting and the use of particle-forming materials with established biocompatibility (31–33) were considered primarily in the current formulation approach, the simplicity of the formulation design achieved through multifunctionality of its elements is also noteworthy. Zinc employed as an ion-pairing agent forms a complex coordination structure with oleate to produce a solid matrix, where 1 zinc cation interacts with 4 oleate anions (34). As a cation, zinc also has exceptionally high affinity for Ad previously exploited for vector purification (35). Its essential role in supporting the high transduction capacity of MNP(Ad)s is evidenced by the substantially greater gene transfer efficiency of the latter in comparison to particles prepared with calcium instead of zinc as the ion-pairing agent (See Supplemental Fig. S3E, F). Another structural component, oleate, first acts as the colloidal stabilizer of nanocrystalline iron oxide (36), and subsequently becomes part of the particle matrix providing it with strong lipophilicity. Notably, Ad possessing several hydrophobic regions in its capsid proteins (37) was previously shown to strongly associate with lipophilic substrates through hydrophobic interactions (38). Thus, both zinc and oleate promote effective vector incorporation, while the high hydrophobicity of the zinc oleate matrix may also play an important role in Ad protection from inactivation by restricting access for destabilizing agents. Finally, Pluronic F-127 is a nonionic surfactant providing steric stabilization and enabling production of MNPs with a narrow size distribution in the range optimal for effective magnetic guidance and safe in vivo use. In addition, it functions as a lyoprotectant, helping to preserve the transduction capacity of Ad in MNPs subjected to the drying stress during lyophilization (See Supplemental Fig. S1), which was previously shown to substantially reduce activity of adenoviral preparations (39). Thus, this formulation approach relies on the few rationally selected, biocompatible elements for making a versatile carrier with a simple design that addresses a number of prerequisites for effective, magnetically driven gene transfer in vitro and in vivo.

The 2-source magnetic targeting strategy employed here for site-specific gene delivery to stented arteries is another important determinant of the effectiveness of the present experimental approach. The inability to target nonsuperficially located sites in humans using a single magnet as the field source remains one of the principal limitations to the clinical applicability of magnetic targeting strategies (40). The recently developed alternative magnetic guidance scheme where a uniform magnetizing field and a magnetizable stent are used in combination to generate a highly focused magnetic force capturing MNPs in the stented region (41) can potentially overcome the above limitation in the therapeutic context of stent angioplasty. The feasibility of this approach was previously demonstrated with magnetically targeted delivery of small-molecule pharmaceuticals and cells (14, 15). In the present study, this strategy was successfully applied to achieve MNP(Ad)-mediated, effective, and target-specific gene transfer to stented arteries, whose essential dependence on applying magnetic guidance was confirmed by the results of both live animal bioluminescent imaging and direct analysis of the reporter transgene activity in homogenized tissue samples. The notable reduction in the local transgene expression toward d 9 post-treatment and the low yet detectable levels of reporter activity found in the liver and spleen tissues of magnetically treated animals suggest that this targeted gene delivery strategy can be further optimized by using MNP formulations of Ad vectors devoid of viral genes (namely, gutless Ad) and/or encoding nonimmunogenic, preferably endogenous, therapeutic transgenes to achieve prolonged duration of local transgene expression. In addition, the high target:nontarget ratio provided by magnetically guided delivery can be complemented by selective expression using Ad vectors constructed with vascular cell-specific promoters (2).

From the pharmacologic perspective, if applied site- or tissue-specifically and aimed at properly chosen molecular targets, gene therapy can offer a significant advantage over conventional therapeutics by converting cells into factories generating biologically active agents in situ. In the context of restenosis therapy, this can be particularly beneficial as previous studies have shown that drug-eluting stents may cease to provide therapeutically adequate drug levels in the arterial wall long before their drug payload is exhausted, with as much as 90% of the drug amount permanently retained in the stent coating (42). In contrast, gene therapeutic strategies can provide continuous in situ production of molecular agents possessing pharmacologic activity, and their efficacy can be further amplified by the bystander effect if the transgenic protein is an enzyme generating high levels of a small-molecule effector capable of acting on targets located at a distance from the transgene-expressing cell. Considering targeted gene delivery as a potential antirestenotic strategy, NO synthase (NOS)/NO are a promising enzyme-effector system (2) as NO is an endogenous small molecule that can inhibit several processes contributing to the early events in the restenosis pathophysiology, including platelet aggregation and adhesion to vascular endothelium and smooth muscle cell proliferation (43). Thus, magnetically guided delivery of MNP(iNOSAd)s enabling enhanced NO production by vascular cells without adversely affecting their viability as demonstrated in this study can potentially provide the basis for a viable candidate strategy for preventing in-stent restenosis.

CONCLUSIONS

The novel zinc oleate-based MNP formulation presented herein and designed for magnetically guided adenoviral gene transfer to cells of the blood vessel wall addresses several prerequisites for a safe and effective gene delivery carrier, including protection of the Ad vector from inactivation, CAR-independent processing, and greatly enhanced magnetically driven transduction. These formulation properties demonstrated in vitro in cultured vascular cells translated into high arterial levels of transgene expression achieved site-specifically in the rat carotid model of stent angioplasty using the uniform field-based 2-source magnetic targeting approach. Magnetically targeted delivery of the MNPs formulated with Ad has the potential to provide sustained, therapeutically adequate local levels of transgene expression in stented arteries achievable with vector doses considerably reduced in comparison to free Ad, and represents a promising site-specific delivery strategy for treating a variety of cardiovascular disorders, including in-stent restenosis therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gary Friedman (Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for advising on the magnetic delivery strategy, and NuMED, Inc. (New York, NY, USA) for providing rat angioplasty catheters.

This research was supported in part by American Heart Association Scientist Development grants (I.F. and M.C.), U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL 094816 (R.J.L.), and The William J. Rashkind Endowment of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- Ad

- adenovirus

- BAEC

- bovine aortic endothelial cell

- CAR

- coxsackie-adenovirus receptor

- iNOS

- inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MNP

- magnetic nanoparticle

- MNP(Ad)

- magnetic nanoparticle loaded with adenovirus

REFERENCES

- 1. Seymour L. W., Fisher K. D. (2011) Adenovirus: teaching an old dog new tricks. Hum. Gene. Ther. 22, 1041–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fishbein I., Chorny M., Levy R. J. (2010) Site-specific gene therapy for cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 13, 203–213 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shayakhmetov D. M., Gaggar A., Ni S., Li Z. Y., Lieber A. (2005) Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J. Virol. 79, 7478–7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams P. D., Ranjzad P., Kakar S. J., Kingston P. A. (2010) Development of viral vectors for use in cardiovascular gene therapy. Viruses 2, 334–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tresilwised N., Pithayanukul P., Holm P. S., Schillinger U., Plank C., Mykhaylyk O. (2012) Effects of nanoparticle coatings on the activity of oncolytic adenovirus-magnetic nanoparticle complexes. Biomaterials 33, 256–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beer S. J., Matthews C. B., Stein C. S., Ross B. D., Hilfinger J. M., Davidson B. L. (1998) Poly (lactic-glycolic) acid copolymer encapsulation of recombinant adenovirus reduces immunogenicity in vivo. Gene Ther. 5, 740–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mok H., Park J. W., Park T. G. (2007) Microencapsulation of PEGylated adenovirus within PLGA microspheres for enhanced stability and gene transfection efficiency. Pharm. Res. 24, 2263–2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner P., Petch A., Al-Rubeai M. (2007) Encapsulation of viral vectors for gene therapy applications. Biotechnol. Prog. 23, 423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Paolo N. C., Shayakhmetov D. M. (2009) Adenovirus de-targeting from the liver. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 11, 523–531 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coughlan L., Alba R., Parker A. L., Bradshaw A. C., McNeish I. A., Nicklin S. A., Baker A. H. (2012) Tropism-modification strategies for targeted gene delivery using adenoviral vectors. Viruses 2, 2290–2355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alfonso F. (2010) Treatment of drug-eluting stent restenosis the new pilgrimage: quo vadis? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2717–2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aminian A., Kabir T., Eeckhout E. (2008) Treatment of drug-eluting stent restenosis: An emerging challenge. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 74, 108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gruchala M., Roy H., Bhardwaj S., Yla-Herttuala S. (2004) Gene therapy for cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 407–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chorny M., Fishbein I., Yellen B. B., Alferiev I. S., Bakay M., Ganta S., Adamo R., Amiji M., Friedman G., Levy R. J. (2010) Targeting stents with local delivery of paclitaxel-loaded magnetic nanoparticles using uniform fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 8346–8351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polyak B., Fishbein I., Chorny M., Alferiev I., Williams D., Yellen B., Friedman G., Levy R. J. (2008) High field gradient targeting of magnetic nanoparticle-loaded endothelial cells to the surfaces of steel stents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 698–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bryan N. S., Grisham M. B. (2007) Methods to detect nitric oxide and its metabolites in biological samples. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 645–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Brien J., Wilson I., Orton T., Pognan F. (2000) Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5421–5426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fishbein I., Alferiev I., Bakay M., Stachelek S. J., Sobolewski P., Lai M., Choi H., Chen I. W., Levy R. J. (2008) Local delivery of gene vectors from bare-metal stents by use of a biodegradable synthetic complex inhibits in-stent restenosis in rat carotid arteries. Circulation 117, 2096–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ridgway J. P. (2010) Cardiovascular magnetic resonance physics for clinicians: part I. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 12, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carpi F., Pappone C. (2009) Stereotaxis Niobe magnetic navigation system for endocardial catheter ablation and gastrointestinal capsule endoscopy. Expert Rev. Med. Devices. 6, 487–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neurath A. R., Stasny J. T., Rubin B. A. (1970) Disruption of adenovirus type 7 by lithium iodide resulting in the release of viral deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Virol. 5, 173–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pandori M. W., Sano T. (2005) Chemically inactivated adenoviral vectors that can efficiently transduce target cells when delivered in the form of virus-microbead conjugates. Gene Ther. 12, 521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chorny M., Fishbein I., Alferiev I. S., Nyanguile O., Gaster R., Levy R. J. (2006) Adenoviral gene vector tethering to nanoparticle surfaces results in receptor-independent cell entry and increased transgene expression. Mol. Ther. 14, 382–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rissanen T. T., Yla-Herttuala S. (2007) Current status of cardiovascular gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 15, 1233–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Volpers C., Kochanek S. (2004) Adenoviral vectors for gene transfer and therapy. J. Gene Med. 6 1, S164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duffy M. R., Parker A. L., Bradshaw A. C., Baker A. H. (2012) Manipulation of adenovirus interactions with host factors for gene therapy applications. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 7, 271–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coughlan L., Vallath S., Gros A., Gimenez-Alejandre M., van Rooijen N., Thomas G. J., Baker A. H., Cascallo M., Alemany R., Hart I. R. (2012) Combined fiber modifications both to target alphanubeta6 and detarget CAR improve virus toxicity profiles in vivo but fail to improve anti-tumoral efficacy over Ad5. Hum. Gene Ther. 23, 960–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kempe H., Kates S. A., Kempe M. (2011) Nanomedicine's promising therapy: magnetic drug targeting. Expert Rev. Med. Devices. 8, 291–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chorny M., Fishbein I., Adamo R. F., Forbes S. P., Folchman-Wagner Z., Alferiev I. S. (2012) Magnetically targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to injured blood vessels for prevention of in-stent restenosis. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc. J. 8, 25–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beringer G. M. (1890) Oleates. Pharm. J. Trans. 20, 676–678 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wolfrum C., Spener F. (2000) Fatty acids as regulators of lipid metabolism. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 102, 746–762 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eide D. J. (2006) Zinc transporters and the cellular trafficking of zinc. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 711–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weissleder R., Stark D. D., Engelstad B. L., Bacon B. R., Compton C. C., White D. L., Jacobs P., Lewis J. (1989) Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 152, 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barman S., Vasudevan S. (2006) Contrasting melting behavior of zinc stearate and zinc oleate. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee D. S., Kim B. M., Seol D. W. (2009) Improved purification of recombinant adenoviral vector by metal affinity membrane chromatography. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 640–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chorny M., Hood E., Levy R. J., Muzykantov V. R. (2010) Endothelial delivery of antioxidant enzymes loaded into non-polymeric magnetic nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 146, 144–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Q. G., Lindman K., Wadell G. (1997) Hydropathic characteristics of adenovirus hexons. Arch. Virol. 142, 1307–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Singh R., Kostarelos K. (2009) Designer adenoviruses for nanomedicine and nanodiagnostics. Trends Biotechnol. 27, 220–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Talsma H., Cherng J., Lehrmann H., Kursa M., Ogris M., Hennink W. E., Cotten M., Wagner E. (1997) Stabilization of gene delivery systems by freeze-drying. Int. J. Pharm. 157, 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pfeifer A., Zimmermann K., Plank C. (2012) Magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Pharm. Res. 29, 1161–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yellen B. B., Forbes Z. G., Halverson D. S., Fridman G., Barbee K. A., Chorny M., Levy R., Friedman G. (2005) Targeted drug delivery to magnetic implants for therapeutic applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 293, 647–654 [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Beusekom H. M., Schoemaker R., Roks A. J., Zijlstra F., van der Giessen W. J. (2007) Coronary stent healing, endothelialisation and the role of co-medication. Neth. Heart J. 15, 395–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naseem K. M. (2005) The role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular diseases. Mol. Aspects Med. 26, 33–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.