Abstract

African-Americans and Blacks have low participation rates in clinical trials and reduced access to aggressive medical therapies. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a high-risk investigational but potentially curative therapy for sickle-cell disease (SCD), a disorder predominantly seen in African-Americans. We conducted focus groups to better understand participation barriers to HCT clinical trials for SCD. Nine focus groups of youth with SCD (n=10) and parents (n=41) were conducted at three sites representing the Midwest, South Atlantic and West South Central US. Main barriers to clinical trial participation included gaps in knowledge about SCD, limited access to SCD/HCT trial information and mistrust of medical professionals. For education about SCD/HCT trials, participants highly preferred one-on-one interactions with medical professionals and electronic media as a supplement. Providers can engage with sickle cell camps to provide information on SCD/HCT clinical trials to youth and local health fairs for parents/families. Youth reported learning about SCD via computer games; investigators may find this medium useful for clinical trial/HCT education. African-Americans affected by SCD face unique barriers to clinical trial participation and have unmet HSCT clinical studies education needs. Greater recognition of these barriers will allow targeted interventions in this community to increase their access to HCT.

Keywords: Sickle Cell Disease, Focus Groups, Clinical Trial Participation, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, Mistrust

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited red blood cell disorder caused by abnormal hemoglobin. Persons afflicted with SCD are subject to painful crises, life threatening infections, progressive organ damage and premature mortality. In the United States, SCD primarily affects individuals of African descent and 1 of every 400 African-American newborns has SCD. Because of the complicated nature of the disease and its potentially devastating consequences, it is generally recommended that children with SCD participate in comprehensive care programs. The major features of SCD management include prevention and treatment of acute manifestations as well as interventions to delay or prevent chronic organ damage.

Hydroxyurea which, promotes hemoglobin F production and interferes with sickle hemoglobin polymerization within the red cell has proven efficacy in patients with recurrent SCD related events, including pain crisis and acute chest syndrome.1–4 However, it is mildly myelosuppressive and fears of leukemia and infertility as complications and problems with adherence with daily dosing have limited its widespread use.5–6 Chronic red cell transfusion, aimed at dilution of sickle red cell hemoglobin, is also effective therapy but may lead to iron overload and allo-immunization.7–10 Cure of SCD using gene therapy is an area of ongoing research.

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) using a related or alternate donor is a novel and potentially curative therapy for SCD.11–13 Barriers to widespread applicability of this treatment modality have included risks of early and long-term toxicity and uncertainty expressed by clinicians regarding appropriate selection of patients.11,14 Lack of a suitable HLA-identical donor has also been identified as a major barrier to HCT.11 The increasing options among treatment strategies available for children with SCD presents a challenge in choosing the best treatment option for an individual patient.15

In general, African-Americans have incomplete access to intensive medical therapy across a broad spectrum of medical conditions.16 Reasons for this include limited access to health care expense coverage, socio-cultural factors, suboptimal access to information, and health care provider bias.17–19 African-American participation in clinical research and clinical trials is low in general,17,20–21 including trials specific to SCD22. Low participation can threaten the generalizability of research findings to these populations, especially when the disease of interest is over-represented in this minority group. Using focus groups, we explored barriers to clinical trial participation perceived among the African-American and Black population, both in general, as well as specific to clinical trials that offer HCT as a treatment option for SCD. A secondary goal of this study was to identify optimal ways to communicate information about clinical trials to the African-American and Black population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Focus Groups

This study employed social science research techniques, using semi-structured focus group discussions to obtain qualitative data in a systematic and verifiable manner. The value of qualitative research lies in the particular description and themes developed in context of a specific site.23 The goal of a focus group is to gather opinions and attitudes from a targeted sample of a population. The intent of qualitative inquiry is not to generalize findings to individuals, sites or places outside of those under study23 but rather, to provide understanding from the respondent’s perspective24.

The study was conducted by the National Marrow Donor Program® (NMDP), a non-profit organization that facilitates unrelated donor and umbilical cord blood HCT through an international network of 170 transplant centers, 50 donor centers, 37 cooperative donor registries, and more. Focus group participants were recruited by HCT physicians, nurse coordinators, and social workers at three comprehensive SCD clinics near or affiliated with the NMDP network transplant centers: University of Illinois at Chicago, Emory University/Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas. These locations were selected based on geographical differences, the population size of the African-American and Black community, and the presence of comprehensive sickle cell programs and active pediatric HCT programs. Participants were recruited through word-of-mouth discussions and distribution of literature at a major sickle cell treatment program in each city. Fliers were mailed (approximately 1500) to potentially eligible individuals who were not scheduled for clinic visits during the recruitment period. Additional fliers were made available in the SCD clinics, at Sickle Cell Education Day (150 attendees), and the SCD Transition Fair (number of attendees not known). Potential participants were instructed to contact a central screener by telephone.

Eligible participants included: (1) African-American and/or Black parents of children, ages 2–16, with SCD; and (2) African-American and/or Black youth, ages 12–16, with SCD. Separate focus groups were conducted for parents and youth. Only one person per household was allowed to participate. Individuals unable to read and understand the English language were excluded from the study. Four potential participants were found to be ineligible via the screening process due to: no real pain episodes in the last 2 years; contact was not the primary guardian (grandparent); schedule/job conflicts; and parent with child with SCD age 1.

The focus groups were conducted in hotel meeting rooms near the hospital facilities and were accessible by public transportation. The environment was conducive to sharing, listening and responding. Incentives were provided in the form of modest-value gift cards and travel allowances. For the parent focus groups, participants received a $75 gift card and $25 travel allowance. In regards to the youth groups, participants (youth) received a $50 gift card, a parent received a $25 gift card and $25 travel allowance.

An African-American professional facilitator conducted the focus groups while a health services research professional from NMDP took notes, distributed gift cards and provided general assistance. A social worker from the NMDP was also present at the discussion site to provide counseling to participants as needed. The parent sessions each lasted two hours while the youth sessions lasted one hour. Parent and youth semi-structured discussion guides designed by the study team were used by the focus group moderator to elicit responses from study participants.

Elements of the focus group discussion guide including how to initiate the discussion and key focus group questions are presented. The focus group discussion guide served to foster an environment of trust and open communication among focus group members and the moderator and review participants’ rights prior to addressing key research questions (Table 1). The key focus group questions were provided to the moderator to ensure that research questions were addressed, the focus group stayed on track and the discussion naturally progressed from easier questions to potentially more challenging questions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Focus Group Semi-Structured Discussion Guide: Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation of African-American and Black Youth with Sickle Cell Disease and Their Parents

Discussion Initiation

|

Focus Group Ground Rules

|

Disclosure and Participant Introductions

|

Table 2.

Key Focus Group Research Questions: Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation of African-American and Black Youth with Sickle Cell Disease and Their Parents

|

Parent Group (whose child with SCD is age 2 to 16 years)

|

|

|

Youth Group (ages 12–16)

|

|

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the NMDP and the three participating centers. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the youth participants and from the parent participants.

Data Analysis

All focus group sessions were audio taped and transcribed by the moderator. Qualitative analysis was performed to summarize data into relevant themes about barriers to participation in SCD focused clinical trials, including HCT, and to identify optimal ways to communicate information about clinical trials. Notes taken during discussion were compared with transcribed content. Data from all transcripts were reviewed and sorted by three independent sources experienced in content analysis to identify consistent themes. Themes were identified through an iterative process by building categories (themes) that were mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Subcategories were identified to allow for greater discrimination and differentiation.24 The reviewers independently conducted thematic analysis for saturation of categories of interest and repeating themes and patterns, as is recommended for qualitative data analysis.25–27 Themes were then compared for consistency and to resolve discrepancies in meaning.24 In this paper, participant quotes are used to support key themes and to show the diversity of opinions gathered during the focus group discussions.

RESULTS

Nine focus groups were held in Chicago (one adult and one pediatric group), Atlanta (three adult and one pediatric group), and Dallas (two adult and one pediatric group). Overall 41 parents and 10 youth with SCD participated (ages of enrolled participants were 12–16). Among participants, 80% were adult (93% employed), 98% were insured and 80% lived within 30 miles from the medical facility (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group Participants by Site

| Characteristics | Chicago N=9 % (n) |

Dallas N=11 % (n) |

Atlanta N=31 % (n) |

Total N=51 % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 55.5 (5) | 63.6 (7) | 77.4 (26) | 74.5 (38) |

| Male | 44.5 (4) | 36.4 (4) | 16.1 (5) | 25.5 (13) | |

| Focus Group | Adult | 55.5 (5) | 81.8 (9) | 87.1 (27) | 80.4 (41) |

| Youth | 44.5 (4) | 18.2 (2) | 12.9 (4) | 19.6 (10) | |

| Child’s Type of SCD | SS (HbSS) | 22.2 (2) | 72.7 (8) | 74.2 (23) | 64.7 (33) |

| SC (HbSC) | 11.2 (1) | - | 16.1 (5) | 13.7 (7) | |

| Sβ-thalassemia | 22.2 (2) | - | 9.7 (3) | 9.8 (5) | |

| Unknown | 44.4 (4) | 27.3 (3) | - | 11.8 (6) | |

| Number of Episodes* Last Year | 0–1 | 11.1 (1) | - | - | 2.0 (1) |

| 2–5 | 66.7 (6) | 81.8 (9) | 61.3 (19) | 66.7 (34) | |

| 6–10 | - | 9.1 (1) | 25.8 (8) | 17.6 (9) | |

| 11 or more | 22.2 (2) | 9.1 (1) | 12.9 (4) | 13.7 (7) | |

| Employment Status (Participant) | Employed | 66.7 (6) | 90.9 (10) | 71.0 (22) | 74.5 (38) |

| Unemployed | 33.3 (3) | 9.1 (1) | 29.0 (9) | 25.5 (13) | |

| Employment Status (Partner/Youth’s Father) | Employed | 44.4 (4) | 18.2 (2) | 51.6 (16) | 43.1 (22) |

| Unemployed | - | - | 6.5 (2) | 4.0 (2) | |

| Other | 55.6 (5) | 81.8 (9) | 41.9 (13) | 52.9 (27) | |

| Insurance Status | Insured | 100.0 (9) | 100.0 (11) | 96.8 (30) | 98.0 (50) |

| Uninsured | - | - | 3.2 (1) | 2.0 (1) | |

| Distance from Medical Facility (miles) | 1–30 | 100.0 (9) | 81.8 (9) | 74.2 (23) | 80.4 (41) |

| 31–60 | - | 18.2 (2) | 22.6 (7) | 17.6 (9) | |

| More than 60 | - | - | 3.2 (1) | 2.0 (1) |

Number of times child was hospitalized or had to seek treatment from any clinical settings for complications due to sickle cell disease (SCD) such as pain crisis, respiratory problems, stroke, etc.

We report content analysis dominant themes on three main areas: the perceived barriers to clinical trial participation in general and in particular HCT as therapy for SCD; gaps in education of SCD; and respondents’ preferences for clinical trial education.

Parent Groups

Barriers to SCD Clinical Trial Participation including HCT clinical trials (Theme I)

Overall, respondents agreed that certain barriers prevented clinical trial participation. These included: limited access to sufficient information and resources, perceptions of HCT risks as high, and lack of trust of medical professionals. Additional responses related to Theme I are reported in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Focus Group Responses: Perceived Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation (Theme I)

| Access to Information |

|---|

| Personal Awareness |

| 1. “I don’t think that we’re really approached as much. Say for instance if you’re at the doctor’s office and there’s some information, it’s kind of hidden away. Even the billboard that’s up about the clinical trial that we can participate in. We’re so focused on let’s get in here and get out because we’ve got this to do, you’re not taking the time to read that. Most of us with the disease, you’re not taking the time to inform yourself as much…you’re just trying to deal with it every day and until you’re faced with that situation, because every case is so different, you’re trying to get through the day. You’re trying to say Ok, I hope that I don’t have to deal with this boss to ask for this time off, to, so you’re just trying to deal. You’re not taking the time to educate yourself. So I don’t know how the clinical studies are, how they choose the people to be in them, but I know that I haven’t been approached. A lot of times I’ll hear from a friend oh, I got some information about a clinical trial, and the only reason they want to participate, whether it’s Sickle Cell or not, for the money. So I don’t know why we’re not approached, but if it’s because information is out there, we’re overlooking it.” |

| Public Awareness |

| 2. “One of the things I think about is…they have no like agents that will go out there and really, like lack of education would be one thing. Like when you, if there’s a rally for cancer, I mean…you can see it everywhere on the news, it’s being covered. But who cares about Sickle Cell Disease? You don’t have any agent to go out and say Ok, this is what Sickle Cell is all about, what do we need to do, we don’t have it.” |

| 3. “I think mass media would be good, because I know when I see stuff on the news, they’re saying someone was cured from Sickle Cell, it lights a fire” |

| 4. “That’s huge, but the thing that we have to realize, if nobody in our community is seeing about putting these commercials on TV, we’re not going to see it. It’s happening in other states, and if I’m not mistaken, the largest population in The U.S. of Sickle Cell, right here in Atlanta, if I’m not mistaken. But there’s an organization that’s looking to do that.” |

| Variation in information provided |

| 5. “Mostly written. The first time they approached me about the STOP study I was not given any information and I requested to see the statistics and what’s going on. So it was mostly written stuff that they gave me.” |

| 6. “I don’t think it’s harder. I don’t think we’re approached because it’s not, I don’t see it…my personal opinion, that like we’re not important to some extent. Like you know, it’s not a disease important enough, serious enough, but it’s very serious. And I don’t think with the lack of information that’s even given to us as the parents or the ones that’s going through it that no one comes to take the time to listen to what you have to say. You know, we don’t want to just be approached for questioning, but understand what we go through on a daily basis.” |

| Health Literacy |

| 7. “Sometimes we can’t understand it. Sometimes you need to write it in laymen’s terms and not in such technical language.” |

| Education |

| 8. “Mine’s piggyback on her. It’s education or lack of education. And I’m not meaning just in our own field of Sickle Cell, but the majority of us, our education level is not that high, so they don’t know what to ask, they don’t know where to go. They don’t know what to look for due to education, their lower education standards.” |

| Economic Factors |

| 9. “Because there is, I would say resources. If we as African-American people don’t have the access to Internet or the access to what we feel like is good information compared to our white counterparts where they get good information, I think that causes us to back up…I would say good information is where you can get the whole fact and not hiding any side effects or hiding what this drug is produced from.” |

| 10. “Most of us with the disease, you’re not taking the time to inform yourself as much…you’re just trying to deal with it every day and until you’re faced with that situation, because every case is so different, you’re trying to get through the day. You’re trying to say Ok, I hope that I don’t have to deal with this boss to ask for this time off, to, so you’re just trying to deal.” |

| Trust |

| 11. “I don’t know, like I like to be around older people, you know, age comes wisdom, and they will say a lot of times that the government used to do different stuff on minorities, so they still have that mindset. And a lot of times that mindset filters down to your children, so a lot of times you’re more hesitant to jump into something because even though you know in the back of your mind that’s not true, but Grandma said long time ago that that was something that was done. So we’re not very receptive to…we say let them try it, if it work for them then…” |

| 12. “Just whether Hydroxyurea would be an option instead of transfusions. They wanted to see if it worked. (unintelligible) and all those types of things. I think he was basically…I didn’t feel comfortable doing it because the doctor, it just seemed like he wanted to be the first one to see that the connection to Hydroxyurea worked better than chronic transfusions, so it just…” |

| Geographic Distance |

| 13. “Well, a lot of time they have it in different cities or something and it’s hard for us to get to them, get to clinical trials and stuff like that.” |

Table 5.

Focus Group Responses: Perceived barriers to HCT as a treatment for SCD (Theme I)

| Lack of Knowledge and Education About Bone Marrow |

| 1. “Because a lot of African-Americans don’t know anything about bone marrow transplants, because they’re not being informed like…maybe a lot of them take their children, like we do, to the clinics. Maybe a lot of them don’t read the pamphlets. I see that’s about the only way you can get any type of information is to read.” |

| Financial Cost |

| 2. “I think (unintelligible) perception that the cost implication. Of course it costs money but I wouldn’t place a cost on any life of my family. I think there’s a misperception that there are not a lot of people that have medical insurance. That they may not be willing or able to raise money for a transplant. So I think those are the two misperceptions I think are out there.” |

| 3. “Another thing is finances. It is expensive!” |

| Psychosocial |

| 4. “I think the discomfort of being a donor, because I remember when we first went to get tested my sister’s like oh, is he going to be a donor, that’s a lot of pain in there. I’m thinking if it ever came down to a decision it would probably be a hard decision to make. But if I had a chance to save my child.” |

| 5. “I was going to say I think it’s sometimes our spirit, for some African-Americans, our spiritual background in terms of we may not always be aware of what’s available in terms of technology and medicine and it’s more kind of just let God do whatever. But there may be some medical things available to us that can help us and heal us and cure us.” |

| 6. “Fear, because when they tell you that they can’t give you a percentage of if they’re going to make it out or not, especially when you don’t have a perfect match. When they can’t give you a percentage of after day one, they call it day one because they start all over. It’s like starting a brand new life. They’re saying we don’t know if she’s going to make it out or not, and we’ve only done three cases in The United States, and two of them didn’t make it and one made it, but is on a lot of medication still. So, you know a lot of stress.” |

| Trust Issues |

| 7. “Parents are too afraid to question the doctors because they think that the doctors know it all, and that they’re afraid to tell the doctor can I get a second opinion, or where can I go to get a second opinion. So I think a lot is afraid to ask questions of your doctors.” |

| System Barriers |

| 8. “There’s a booth set up I think at the state fair and I want to say its bone marrow but everything around it says cancer or leukemia. I don’t see one sickle, no nothing, but it all says cancer. And Baylor is really big on bone marrow, Baylor downtown, but it’s strictly geared toward cancer. It’s not geared towards Sickle Cell.” |

| 9. “Not having any idea what it is. No information…they just think that we have basic illnesses because we’re black and being that there are options, they don’t want to be open to the options, is what I’m saying.” |

Access to information/resources

Limited access to information and resources about SCD clinical trials was cited by almost all participants. Financial constraints also hindered parents’ ability to take time off from work to support their child’s participation in clinical trials.

Respondents expressed concern regarding access to accurate, up-to-date information about SCD, treatment options, and the implications of sickle cell trait. The stigma associated with SCD trait and the disease was as a barrier to open communication among families and communities. For most families, little or no information about trait was shared. Sample comments related to this theme included:

“I don’t think they’re available. I think if they asked us to do them I think we’d be more willing to participate… I know I would if I was asked because I would have done that one that she mentioned. If they’d asked me I would have done that because I feel that’s something I would like to know.”

“I was familiar with Sickle Cell Disease; however I didn’t know I carried a trait.”

“I knew about the disease. I knew it was kind of along the line of cancer, but I never had any reason to research it or read about it. But I had heard about it, but it didn’t impact me until my daughter had it.”

“I’d say lack of public knowledge. There’s no, I don’t see the commercials, like the cancer.”

Perceptions of HCT

Lack of information about HCT as a potential therapy for SCD was identified as a barrier to participation in clinical trials investigating HCT. The majority of participants had heard about HCT. Parents learned about transplant from a variety of sources including medical staff, media stories, other parents, and health fairs. Some parents conveyed knowledge about the possibility of using a newborn child’s umbilical cord blood as a cell source for transplant. Barriers identified in pursuing clinical trials of HCT for SCD included fear of transplant and its complications, concerns about the safety for sibling donors and the length of recovery and costs related with this procedure.

“The doctors don’t really tell you any information about it. It’s there but I don’t think they’re active in seeing that you know; maybe you guys should sponsor a bone marrow drive or anything. They don’t give you any information. It’s not talked about at all.”

“I think there’s a misperception that there’s a lack of interest among the African-American population regarding transplants and donor programs. This is the first one I’ve heard of a clinical trial regarding Sickle Cell Disease and/or bone marrow transplant. And I’ve been around medicine for a long time.”

“It’s expensive so financial, and your time that you have to take off. We were out, and then she had complications, so she was out of school for a year. We were at home for a year.”

Lack of trust of medical professionals

The lack of trust was brought up as a barrier to clinical trial participation in all parent/adult discussions. Participants spoke of mistrust stemming from historical events and retold family generational stories had influenced their trust of others. They conveyed a fear that health care professionals did not share truthful information at all times and that useful information was concealed when minority patients were seeking or receiving medical care. Some mistrust of the physicians and medical team was tied to the belief that physicians were more concerned about their research work than the well being of the patients and family members.

“There’s a lack of trust in medical professionals. Like she was saying, if you look into our history, and I think a lot of people, a lot of black people do not want to, like she said, be tested on, because we don’t even do studies that…and some of it is lack of information, not knowing the studies are out there. But I think a huge part of is it not trusting the medical professionals.”

“I’ll tell you why I think a lot of people, well, from my perspective, are rebellious, kind of reluctant about it is because in history we have been used as Guinea Pigs and we refuse to be used as Guinea Pigs, and being that there is not a lot of education and knowledge, or there’s a lack of knowledge and education about bone marrow because we don’t have the money, we’re not in that bracket that can just go out and get it, we don’t want to be Guinea Pigs for anybody.”

Gaps in Education of SCD (Theme II)

A second major theme was gaps in education and understanding of SCD. This included low awareness of SCD, a lack of knowledge about sickle cell trait, and general misinformation (Table 6).

Table 6.

Focus Group Responses: Gaps in Education and Understanding about Sickle Cell Disease (Theme II)

| Awareness of Disease |

| 1. “I was aware of the disease. I had the trait. But that was basically it. I just knew it existed. With the trait I hadn’t had any problems so that was basically all I knew about it.” |

| 2. “I had a close family friend that had Sickle Cell so that’s how I knew some information about it. Other than that I didn’t know anything about it.” |

| 3. “I knew a little bit about it but not a whole lot. I didn’t find out of course until both my sons were diagnosed with it. The only thing I knew, it came from Africa and there were a couple of kids in my town in Arkadelphia that were diagnosed with it and they had a hard time. But my sons, they haven’t had as hard a time as they did. That’s all I knew about it until they were diagnosed and I started doing research.” |

| 4. “I have it and my sister has it. Back in the ‘70s when I was born my mom and dad knew nothing about it. They both had the trait. So I kind of knew a lot about it but my ex-husband didn’t know if he had the trait or what was really going on with him, so that’s how my daughter got it. But yeah, I did know a lot about it.” |

| 5. “I knew I had the trait since I was younger because back in England everybody has to do the test to see whether you have the trait, whether you have the disease, so I knew I had it. And so I knew a lot about it, actually, because my cousin has SS, my first cousin. And so I was well aware of what it was and the risks and things of that nature. When I got pregnant I knew there was a huge possibility that child, there was a 25% chance because both of us have the trait. And so when she was born I was hoping she didn’t have it. She ended up having it but I knew about it before she was born.” |

| Perceptions of HCT |

| 6. “Really, because one, as far as the one that’s first testing the reading and all those educational skills, there was no harm done. That was Ok. I was reluctant about the drawing of the blood. Just because they did have to stick him and draw the blood but he was Ok with it so I just went along with it.” |

| 7. “So there was no fear factor to it. I mean other than the normal risks that you would associate with doing an MRI, so that were an easy decision to help the process.” |

| 8. “I rejected it because at the time I felt looking at her individual needs I didn’t think she needed that medication. And I also did research on it and like she said, it is a chemotherapy agent and like one of the risks, being a girl, she might not have a child, a deformed child…just too many risks associated with it so I just rejected it.” |

| 9. “I like to feel like I’m helping out, and that’s the biggest thing. I want to make sure that, you know, they’re trying to help me, I want to try to help them. That’s the biggest thing for me. So as long as I don’t feel like my kids are being hurt or they’re not going to get too many needle sticks, different things like that, then I’m all for it.” |

| 10. “For me it was the Baby Hug program with Hydroxyurea and not knowing enough about the program itself and understanding it’s like going through chemo. And again, my kid had not had any serious issues up to that point so I saw no reason to do it.” |

| Misinformation or Lack of Information |

| 11. “Nothing. I thought it was if you get it you die, you just die. When I heard my son had it I just broke down for a year thinking he’s going to die. I’m checking on him every minute. It was scary.” |

Low Awareness of SCD

Low awareness about SCD was tied to limited public awareness campaigns. Others mentioned increased need for school systems and day care centers as ways to promote SCD awareness among the public. School nurses in some instances, were said to be unhelpful when SCD youth became ill at school and had recurring extended absences from school.

“My husband knew about it. He knew he had the trait, and while I was pregnant I asked my doctor, not knowing what I know now, but I asked my doctor to test me to see if I had the trait. And he told me no, because he didn’t administer the proper test. It’s not found in just a regular CBC test. There’s that hypo-Thalassemia something kind of test and that you find it specifically and he didn’t take the time to do that.”

“I knew very little about it. One of my friend’s father actually has sickle cell disease and I wasn’t around it enough to really get a feel for what the clinical manifestations were and what they went through.”

Lack of Knowledge about Sickle Cell Trait

General lack of knowledge and community awareness about sickle cell trait and delay in its diagnosis was also identified by participants as an issue of concern.

“I knew more about it because my biological father had Sickle Cell Anemia and he died from leukemia. And my paternal sister, she also has Sickle Cell Anemia. So from knowing them I knew about Sickle Cell. But I didn’t know that I had the trait until I was pregnant with my first child.”

“I knew that I had the trait but I never thought it was going to be someone else with the trait.”

“I had no idea about Sickle Cell. I have the trait and I didn’t know that until I was pregnant with my son.”

Preferences for Education about Clinical Trials (Theme III)

Respondents’ preferences for education about clinical trials included one-on-one interactions with health professionals and multiple formats for conveying clinical trial information such as use of the internet, pamphlets, booklet, and DVDs. To have information in written format and adequate time to review information the doctor or health care professional was conveying was preferred. Further descriptions of educational preferences specific to one-to-one interactions and media formats appear in Table 7.

“I would like to get the information, maybe a couple weeks before I come in for a doctor’s appointment so I could read over and have questions rather than you bring it to me, you talk to me and give me a few minute to read over it and like what’s your questions.”

“For me, I want to talk to the doctor and spend as much time as I can, but I know for sure the doctor has not time to spend with me. It will never happen. So then send me a letter. Explain to me so that I can get much information and the 15 minutes you have to explain what I’m going to get then, so I get both ways.”

Table 7.

Focus Group Responses: Educational Preferences for Clinical Trials (Theme III)

| One-to-One with Health Care Professional |

| 1. “Give us a brief synopsis of what’s happening or whatever, and then if it’s something we’re interested in when we go to our doctor we’ll take it to our doctors and get it validated that that point, you know anything about this. Oh, Ok, you think it’s good” |

| 2. “We had basically the same thing. To educate we said advanced notice, send the pamphlets out prior to going to the doctor and getting the information so you could have the information. One on one discussion. And as far as who should give the information, the doctors and the nurses and maybe if there could be some parents available who have gone through this or had the clinical, because sometimes I might be more prone to listen to another parent than to listen to a doctor..” |

| 3. “Basically, yeah, mail and then I’ll talk to my doctor after I’ve done my research, see what he’s talking about compared to my research. Then I’ll make my decision.” |

| Educational Information in Different Formats |

| 4. “DVD. Like you can watch it instead of reading it.” |

| 5. “I’d like to see a video or something. Just hey, this is what’s going on. Then they could present it to us in several different ways or what they’re doing in the labs, different things like that.” |

| 6. “Um-hmm, when I get the literature I’d say we got something new for your disorder or whatever. I’ll read it and I’ll let her read it and I’ll ask her what she thinks about it. Is she excited, or I don’t want them poking me or sticking me or whatever, then I would still talk to the doctor about it and I’d give her the pros and cons. We’ll discuss it together.” |

| 7. “Just given out pamphlets that are visible so we can see the information.” |

| 8. “You could have an information booth, whether it’s a permanent fixture within the clinic that just gives all information, whether it’s social events or whatever. An information booth, a go-to reference, place within the clinic that’s available.” |

| 9. “Well, I say after because there’s a tendency that you might forget after the doctor has spoken to you about it. So I figure if you get it through the mail, that’s a follow up from the doctor’s.” |

| 10.”I prefer to get it in the mail because I can read over it and then I can investigate it myself, and then I can be a little abreast when I bring it to my doctor, and he can tell me what he knows about it but I still have a little history on it. If I get it from him, like he said, you’re only in there about 15, 20 minutes so all you’re getting is a brief overview and you really aren’t sure. So I can go on the Internet, see what I can find, talk to other people.” |

| 11.”For outside the doctor speaking just making sure that he gives me literature, maybe that also has links to where I can go and research stuff that’s related to the clinical study as well.” |

Youth Groups

Knowledge of SCD (Theme I)

Youth participants were asked to talk about their initial awareness and knowledge of SCD and reported their earliest memories of SCD were associated with needles, pain, medical staff and being in the hospital. Of the ten youth, some did not recall when they first became aware they had SCD, while others became aware of their disease as early as three years of age. There was variation in the degree to which they shared information about their disease with peers. Youth who engaged in SCD camp programs and events hosted by their treatment centers, which gave them exposure to peers with the same disease, expressed feeling comfortable talking about SCD.

“Yeah, I have a friend that she had the trait and her brother also has the trait. So we kind of explained like what happens sometimes. And I’m gone every month, some months, and they ask me why and I told them why, that I get transfusions and stuff.”

“Yeah, I tell them everything about it, like when we play football, practice and all that,

I’ll be sitting out sometimes because I can’t keep up.”

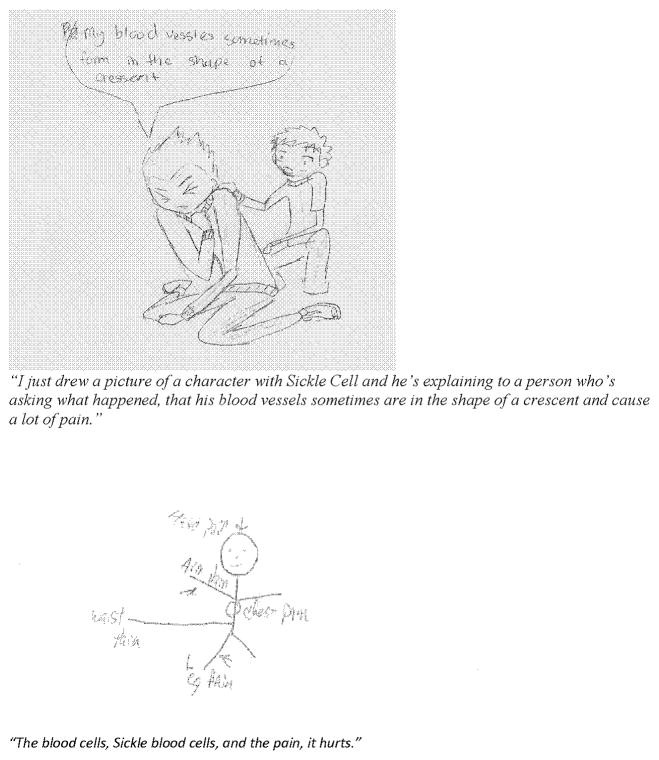

Youth participating in sports appeared more willing to share information about their disease with their teammates who helped them manage behavior to reduce pain crises. The youth were asked to draw pictures or images of what SCD does to the body and to describe their drawing in their own words (Figure 1). Blood cells affected by SCD, images of pain, and physical limitations associated with SCD were expressed.

“I tell them it’s with the red blood cells that don’t carry oxygen. Like they make C’s and I say, like they take over your white blood cells so you get tired quicker and faster.”

“I just drew a picture of a character with Sickle Cell and he’s explaining to a person who’s asking what happened, that his blood vessels sometimes are in the shape of a crescent and cause a lot of pain.”

“In elementary school only one of my friends knew. We had a discussion about does anyone have like diseases and stuff like that, (unintelligible) ourselves. And I told everyone that I had Sickle Cell but they didn’t really care. Then my friend would wonder why I wasn’t there and I told him, and he thought that Sickle Cell was contagious because we were playing a game with noodles and someone tripped me and I ended up biting him in the neck, or on his shoulder. So he had to go see the doctor and they told him it’s not contagious or anything. So they just put ice on him because apparently I bit into him really hard.”

Figure 1.

Sample youth drawings or images of what sickle cell does to the body.

Awareness of Treatment for SCD including HCT (Theme II)

Youth participants reported in detail information about clinical manifestations of SCD and treatment processes. Taking medications, staying hydrated, using heating pads, relaxing and exercising regularly were common approaches described for treating symptoms of SCD. Youth expressed perceived benefits and challenges of the following treatments: blood transfusions; Hydroxyurea; EXJADE; and spleen removal.

“When hemoglobin is low, to get a blood transfusion to get high hemoglobin. Then I won’t have a crisis.”

“To make sure you have healthy blood to circulate through your body.”

“Try to take your mind off the pain and try to think about the things that make you happy and comfortable.”

“Like three weeks ago. I had a pain crisis in my stomach. My liver was enlarged and it had got swollen.”

“EXJADE also help with your bone marrow and take away iron. And nothing really happens if you don’t take it.”

Over half of the youth participants were knowledgeable about HCT as a treatment option and recalled conversations with their parents and doctors.

“My parents had asked about it and I was listening. He said it’s usually used for cancer patients and my parents asked because they heard of someone who had cancer and had to get a bone marrow transplant and also had Sickle Cell and afterwards she didn’t have any symptoms and eventually that the Sickle Cell kind of disappeared. And they said that was unusual and the consequences afterwards were too high.”

“My doctor talked to me when I was in the hospital about it. They found two that are the same. Now they have to contact the people to see if they’re willing to do it.”

“I understand you have to have like a partner to get bone marrow from.”

“It’s like they have to find the exact same blood, like exactly the same blood, and then like they transplant it into you and you still have it but you don’t get sick with Sickle Cell as much. You’d probably only have Sickle Cell crises like once every three years.”

“You are there a long time when you do that.”

Youth referred to their knowledge of clinical trials as “tests” or “getting medicine.” Youth reported their parents informed them in conjunction with someone from their health care team about the clinical trials.

“They told me about it when I was ten or whatever, because I had my surgery, had my gall bladder removed, and they wanted to try it. So at first when I was in the hospital it was like a placebo or whatever. I had to wait a year to see if that was really what it was.”

“The advantage of the test was that I would get paid for doing it, but I continued to take the medicine when I’m off the test.”

Preferences for Education on SCD Treatment including Clinical Trials (Theme III)

Most youth relied on and preferred to get information about SCD and treatment options through personal interactions with their physicians, nurses and parents. Youth who attended SCD camps and health fairs expressed that the comfort they felt in these types of settings helped them to be receptive to learning new information and benefited socially from personal interactions with peers who had SCD.

“Sickle Cell Summer Camp…, it’s just like a regular camp except that it’s wheelchair accessible and it has a nurse’s station and stuff like that. School Nurse can’t tell me if there are other kids w/SCD in school.”

“I like the camp because I benefit there and I help others there.”

“Well, it was a cool experience because seeing how I draw and stuff, when we went to the art room for some contest, I won it. And there was a tree house being built and we did the tree house building design. And the other people and me won it and we got to go to like this huge building during the night and we talked to these adults about how to construct the tree house. It was really cool and it was fun. And like we saw a whole bunch of different people and how they act and you had to try to stay mature there. And they tell you its Ok, you don’t have to try to act like an adult right now, you can have fun and stuff like that.”

Electronic media and the internet were effective ways to supplement the information provided by the health care team and parents. Computers games designed to help youth learn about and manage their disease and to feel more positive about their future and themselves were described.

“Make it kid friendly.”

“Tell why it is important.”

“Doctor gave me like a CD for the computer that tells you a lot about SC. Watch it once a week.”

“I prefer a CD. I got one called Slime-O-Rama where you got to answer a question and at the end you get to slime this guy. Like every question you answer you get a slime ball.”

DISCUSSION

Identification of barriers to participation in clinical trials may reveal specific factors that can be modified to reduce disparate access to clinical trials for African-Americans and Blacks. The results of our study affirm that African-Americans and Blacks have real or perceived barriers to clinical trial participation and limited knowledge about SCD and sickle cell trait. Responses from the focus group discussions highlight key barriers to participation.

In each of the parent discussions, historical medical events such as the Tuskegee experiment were mentioned. Mistrust stemming from historical events is consistent with findings from previous studies and is cited as the most significant barrier to research participation28–30 The length of time the physician spent with the patient was expressed as an indicator of physician concern or lack thereof with the patient’s and family members’ well being. Many participants including the youth felt that they did not have enough time with their medical doctor.

Many parents had limited knowledge of SCD despite having a child with a diagnosis. Few parents realized that they or their partner had the sickle cell trait until after their child was born. The majority admitted being embarrassed about having the trait and talked emotionally about the silence within family members and the community about the disease or trait. Most participants expressed strongly that the silence within the community could be remedied by SCD public awareness campaigns similar to those related to cancer and by increased efforts to bring together those affected by sickle cell disease and public health and school personnel to collaboratively plan and implement successful health promotion events and campaigns in their communities.

Focus group participants were in agreement about the lack of access to clinical trial information and resources. Additional barriers to pursuing clinical trials offering HCT as a specific treatment of SCD were identified. Some parents indicated they would consider transplant as a last resort. Others associated HCT with the treatment of leukemia and other cancers, and few were aware of its curative potential for SCD. A majority of the youth participants had heard about HCT as a potential treatment option and were aware that the treatment option had risks.

Both parent and youth groups had similar preferences for education about clinical trials including those specific to HCT. Both groups talked about electronic media (e.g., DVDs, video clips) and the internet as effective ways to supplement and reinforce the messages from the medical team. Most of the youth preferred to get information about SCD and treatment options through personal interactions with their physicians, nurses and parents. Those who attended SCD camps and health fairs found these environments receptive to learning new information and enjoyed the personal interactions. Not all youth participants had attended SCD camps. One site made creative use of a computer video game to educate patients about SCD. Overall, one-on-one interactions between parents, youth and healthcare professionals were highly preferred.

Our study has limitations. The voluntary nature of the study and inclusion of sites with SCD comprehensive clinics that run research protocols presents an opportunity for bias regarding the population represented in the focus groups. In general, participants were educated, employed, and had medical insurance benefits. It is likely that children with SCD from households with lower educational and socioeconomic status face more barriers and less exposure to clinical trials than was identified in our study. Also, due to low youth enrollment some responses in that age group may not be representative and further research is still needed to facilitate youth participation in SCD clinical trials.

Participation in clinical trials by affected individuals is critical to improving treatments for serious disorders such as SCD. Our study findings suggest that African-Americans affected by SCD face barriers that hinder clinical trial participation and have unique informational needs about clinical trials in general and HCT clinical studies specifically. Medical professionals can engage with sickle cell youth camp or Sickle Cell Education Day management to provide information on SCD/HCT clinical trials to youth and local health fairs for parents and families. Youth learn about SCD from games; investigators may find this medium useful for clinical trial/HCT education. Greater recognition of these barriers will allow clinicians and public health officials to target interventions to further improve patients’, families’ and the communities’ understanding of SCD and its treatment options offered through clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This study was funded by the National Marrow Donor Program®. No honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

For assistance with patient recruitment, we would like to acknowledge Jacqueline Geter, PNP, Michelle Planeaux, CPNP, Betsy Record, PNP, Emily Rudd, MSW, LCSW from Emory University, Shirley Miller from Children’s Medical Center Dallas, and Sandra Gooden, RN, BSN, Daisy Pacelli, MPH, RN, and Shonda King, MSW, LSW from the University of Illinois Medical Center at Chicago. We also acknowledge Lisa Gaines McDonald, MBA from Research Explorers, Inc. for moderating focus groups and Shaveta Nayyar, BDS, and Tammy Payton from the National Marrow Donor Program for assistance with data analysis and manuscript review.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ferster A, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of severe sickle cell anemia: a pediatric clinical trial. Blood. 1996;88:1960–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AP, Davies S, Olujohungbe A. Hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease (Cochrane Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001:2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003;289:1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferster A, Tahriri P, Vermylen C, et al. Five years of experience with hydroxyurea in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2001;97:3628–3632. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stricker RB, Linker CA, Crowley TJ, et al. Hematologic malignancy in sickle cell disease: report of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 1986;21:223–230. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830210212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferster A, Sariban E, Meuleman N. Malignancies in sickle cell disease patients treated with hydroxyurea. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:368–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, et al. Survival in medically treated patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:574. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung EB, Harmatz PR, Lee PD, et al. Increased prevalence of iron-overload associated endocrinopathy in thalassaemia versus sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:574–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosse WF, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, et al. Transfusion and alloimmunization in sickle cell disease. The Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 1990;76:1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olujohungbe A, Hambleton I, Stephens L, et al. Red cell antibodies in patients with homozygous sickle cell disease: a comparison of patients in Jamaica and the United Kingdom. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:661–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolaños-Meade J, Brodsky RA. Blood and marrow transplantation for sickle cell disease: overcoming barriers to success. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:158–161. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328324ba04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoy S. Has stem cell transplantation come of age in the treatment of sickle cell disease? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:813–821. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnamurti L. Hematopoietic cell transplantation: a curative option for sickle cell disease. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24:569–575. doi: 10.1080/08880010701640531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakrabarti S, Bareford D. A survey on patient perception of reduced-intensity transplantation in adults with sickle cell disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:447–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankins J, Hinds P, Day S, et al. Therapy preference and decision-making among patients with severe sickle cell anemia and their families. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:705–710. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF, et al. Why are African-Americans under-represented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethn Health. 1997;2:31–45. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1997.9961813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JNMA. 2002;94:666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassell K, Pace B, Wang W, et al. Sickle Cell Disease Summit: From clinical and research disparity to action. Amer J Hematol. 2009;84:39–45. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zempsky WT, Loiselle KA, McKay K, et al. Do children with sickle cell disease receive disparate care for pain in the emergency department? J Emer Med. 2009;39:691–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Bolen S, et al. Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. 2005;122:290–02. doi: 10.1037/e439572005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams-Campbell LL. Enrollment of African-Americans Onto Clinical Treatment Trials: Study Design Barriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:730–734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters MC, Patience M, Leisenring W, et al. Stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism after bone marrow transplantation for sickle cell anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:665–673. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11787529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor-Powell E, Renner M. Analyzing Qualitative Data. University of Wisconsin Extension; 2003. [Accessed October 17, 2011]. Available at: http://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/g3658-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnard P. A method of analyzing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today. 1991;11:461–466. doi: 10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analyzing qualitative data. BrMJ. 2000;320:114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benkert R, Peters RM, Clark R, et al. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. JNMA. 2006;98:1532–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benkert R, Hollie B, Nordstrom CK, et al. Trust, mistrust, racial identity and patient satisfaction in urban African-American primary care patients of nurse practitioners. J Nurs Scholar. 2009;41:211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]