Abstract

This paper reports the clinical findings, histopathology, and clinical outcome of a rare case of aponeurotic fibromatosis in a dog. The dog was treated with 4 courses of electrochemotherapy using the drugs cisplatin and bleomycin. There was complete remission and the dog was still disease-free after 18 months.

Résumé

Électrochimiothérapie pour le traitement de la fibromatose aponévrotique chez un chien. Cet article présente les résultats cliniques, l’histopathologie et le résultat clinique d’un rare cas de fibromatose aponévrotique chez un chien. Le chien a été traité avec 4 séries d’électrochimiothérapie utilisant les médicaments cisplatine et bléomycine. Il s’est produit une rémission complète et le chien était toujours exempt de maladie après 18 mois.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Fibromatoses are progressively growing, infiltrative, fibroblastic masses that tend to recur after surgical excision (1). Fibromatoses in humans are divided into 2 categories, on the basis of their type and anatomical location: i) superficial (fascial), and ii) deep (musculoaponeurotic) fibromatoses (2). Superficial fibromatoses derive from fascia or aponeurosis, grow slowly, and are usually small. Deep fibromatoses affect deeper tissues, and are more aggressive in terms of growth rate and size at presentation. The term “desmoid tumor” is still widely used in the veterinary literature as a synonym for this latter aggressive type of fibromatosis. Cases of fibromatosis have been reported in the veterinary literature (3).

Electrochemotherapy (ECT) combines the administration of poorly permeant drugs such as bleomycin (transported within the cytoplasm by specific membrane proteins) or drugs like cisplatin (that enter the cell through concentration gradient) (4–6), with the application of permeabilizing electric pulses (EP) that increase the transmembrane flow of drug into the cancer cells. Several cohorts of companion animals affected by soft tissue neoplasms have been enrolled in ECT trials by our group, obtaining high rates of durable local control (7–9).

Case description

A 1-year-old intact male great Dane dog was referred for a large mass of the left hock. The mass grew over 2 mo, starting as a soft swelling that evolved over time into an induration. The dog was bright, alert, and responsive, well-hydrated and in good body condition. A firm, mildly painful at palpation, and poorly circumscribed mass that measured approximately 15 × 5 × 7 cm was present at the left hock. We obtained a complete blood cell count, serum biochemical profile, urinalysis, chest radiographs, and abdominal ultrasonograms. The results of all the tests were within reference limits and the imaging studies were unremarkable.

The tumor was surgically excised; it was deeply connected with the tendons of the digits as well as the adjacent blood vessels, reaching the soft tissues adjacent to the distal tibia, thus preventing wide excision. The sample was fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and hematoxylin-Van Gieson. For immunohistochemistry, the streptavidin-biotin system (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA), was used. The primary antibodies for vimentin, desmin, and S100 (Dako) were applied at room temperature for 1 h at the 1:100 dilution. Van Gieson staining was used to better identify muscle and connective tissue; accordingly, vimentin was adopted to identify cells of mesenchymal origin, desmin to identify muscle cells and S-100 to define cells derived from the neural crest (Schwann cells and melanocytes).

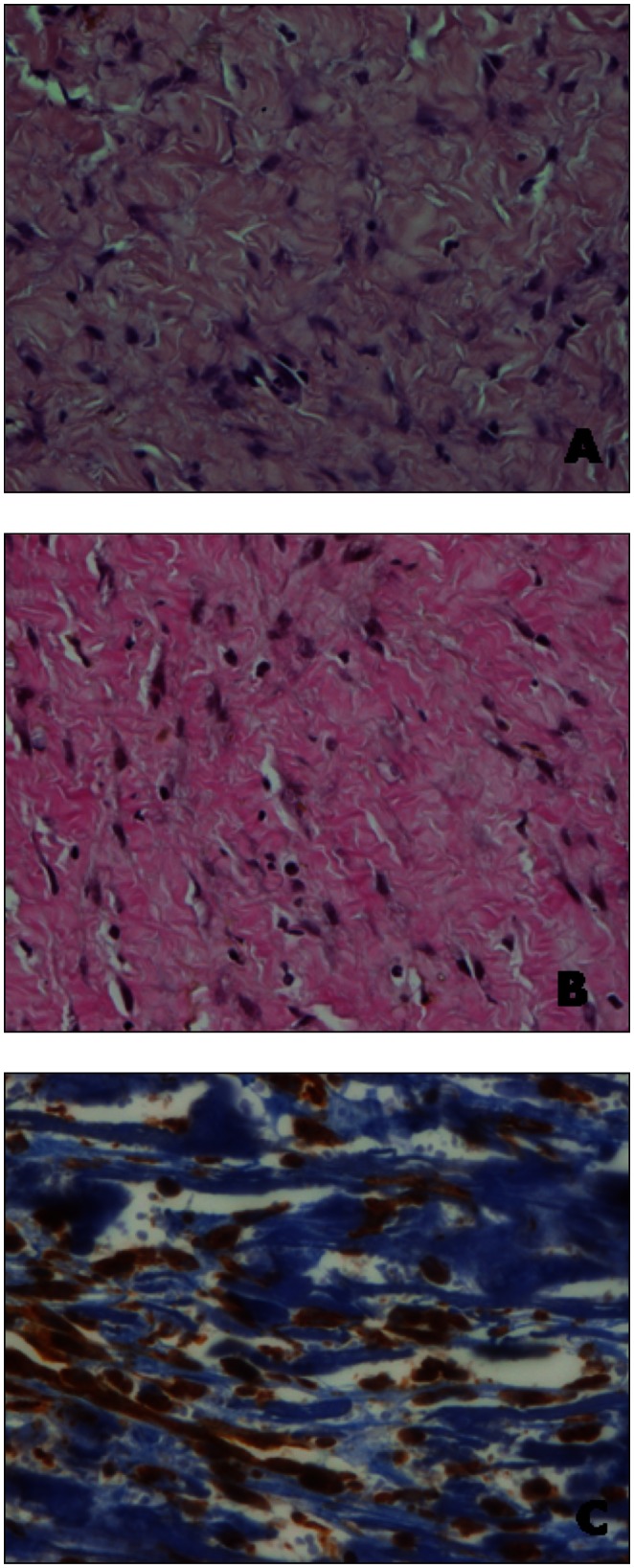

The tumor mass consisted of spindle cells scattered singly or occasionally aligned in fine streaming bundles. Cells were separated by abundant, fibrillar, eosinophilic mature collagen and the number of mitoses observed in ten 40× fields of view was less than 1. The neoplastic tissue was moderately vascularized by small- and medium-sized blood vessels and mild multifocal infiltrates of lymphocytes were observed. The neoplastic cells stained red with Van Gieson stain and were positive for vimentin and negative for desmin and S100 (Figure 1). The histopathological diagnosis was aponeurotic fibromatosis.

Figure 1.

A — Microscopic appearance of the lesion at the time of surgical excision, showing a diffuse infiltrative mass consisting of a moderate number of well-differentiated fibroblasts and an abundance of collagen fibers (Hematoxylin and Eosin, original magnification × 40). B — The collagen fibers stain red with Van Gieson staining (Hematoxylin-Van Gieson, original magnification × 40). C — Vimentin immunostaining shows the neoplastic cells scattered singly or aligned in fine streaming bundles and separated by abundant mature collagen, negative for the immunostaining (ABC method, original magnification × 40).

Two weeks following surgery the tumor recurred, measuring 12 × 8 × 5 cm (Figure 2A). Several options were offered to the dog owners: limb amputation, radiation therapy, or ECT. The owner, due to emotional and financial reasons, elected to have the dog treated with ECT.

Figure 2.

A — The patient at presentation, B — The patient at the time of starting bleomycin based ECT, C — The patient at completion of therapy.

The dog was sedated with a combination of medetomidine (Domitor; Orion Pharma, Milan Italy), 0.01 mg/kg body weight (BW), IM, and propofol (Rapinovet; Intervet, Milan, Italy), 4 mg/kg BW, IM, and the tumor and 1 cm of normally appearing margins were infiltrated with cisplatin (Cisplatino Teva; Teva Italia, Milan, Italy) at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL (total dose 8 mg). Five minutes after the infiltration of the antiblastic agent, trains of 8 biphasic electric pulses (EP) generated by a Chemipulse III portable electroporator (prototype described in reference 8) at 1300 V/cm, lasting 50 + 50 μs each, with 1 ms interpulse intervals, were delivered by means of autoclavable clamp electrodes (9). Adherence and conductance were enhanced by using an electroconductive gel. The dog recovered from the treatment and received a second session 1 wk later, when the neoplasm showed signs of reduction: the size was decreased to 9 × 6 × 4 cm and the lesion was better separated from the surrounding tissues; therefore, a third session was done. After 1 week the tumor size was 8 × 5 × 4 cm and did not shrink further after a fourth weekly ECT session.

Possible reasons for this lack of response were: acquired tumor resistance to cisplatin, uneven drug distribution due to presence of necrotic areas or cancer cell shielding by scar tissue formed within the mass following ECT. In order to have better drug distribution and to counter a possible acquired chemoresistance, the drug bleomycin (Bleoprim; Sanofi Aventis, Milan Italy), 15 mg/m2 was administered systemically before the treatment with intralesional cisplatin and electroporation. The following week the tumor size was 5 × 3 × 2 cm and the consistency was soft (Figure 2B). A final ECT session was done the following week and resulted in complete remission of the neoplasm (Figure 2C).

Throughout the ECT course the dog did not experience chemotherapy-associated toxicoses or side effects. Rechecks consisting of physical examination and ultrasonographic examination of the tumor site were performed every 3 mo. After 18 mo the dog was still in remission.

Discussion

Electrochemotherapy has proven to be a safe and efficacious therapy for the local control of solid neoplasms in companion animals, and its effectiveness is especially strengthened when used in an adjuvant fashion (5–9). The adjuvant ECT is used to sterilize the surgical field after incomplete removal of solid neoplasms, more specifically, it has been successfully applied to canine and feline sarcomas and mast cell tumors (5–9). In certain patients ECT has been used to directly attack specific tumors such as canine melanoma and feline squamous cell carcinoma (10,11). This strategy has two advantages: i) absence of acute and delayed side effects, and ii) possibility of re-treatment in case of tumor recurrence. The use of ECT as a rescue in patients experiencing tumor recurrence after radiation therapy, however, should be carefully evaluated in consideration of a reported severe radiation recall in a cat (12).

Musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis, also known as desmoid tumor, is a condition characterized by the presence of poorly circumscribed fibrous tissue dissecting areas of nearby muscle(s) that has been previously reported in 2 great Danes, an Akita, and a Bernese mountain dog (3,13,14). In all these patients the treatment of choice was aggressive surgery, with the exception of the Bernese mountain dog that only had tumor biopsies and monitoring. In our patient, the involvement of multiple musculoaponeutoric structures prevented the en bloc resection of the mass, requiring alternative therapy.

In humans, although wide surgical excision is frequently the first line of treatment, a multidisciplinary approach is often used that includes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy in consideration of the tendency of the disease to recur due to its infiltrative pattern of growth (2,15). The use of chemotherapy is mostly limited to more clinically aggressive presentations, while radiation therapy is the cornerstone to achieve local control (15,16). In conclusion, the present report describes a low cost, well-tolerated and efficacious treatment option, additional to surgery, for aponeurotic fibromatosis and warrants further investigation in human patients as well. CVJ

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by “Grant 2011” of the Italian Ministry of Health to E.P.S, and by a FUTURA-onlus Grant and a Second University of Naples Grant to A.B. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Allen PW. The fibromatoses: A clinicopathologic classification based on 140 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1977;1:255–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berri RN, Baumann DP, Madewell JE, Lazar A, Pollock RE. Desmoid tumor: Current multidisciplinary approaches. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67:551–564. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182084cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welle MM, Sutter E, Malik Y, Konar M, Rüfenacht S, Howard JE. Fibromatosis in a young Bernese Mountain Dog: Clinical, imaging, and histopathological findings. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21:895–900. doi: 10.1177/104063870902100625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spugnini EP, Porrello A. Potentiation of chemotherapy in companion animals with spontaneous large neoplasms by application of biphasic electric pulses. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:571–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spugnini EP, Vincenzi B, Citro G, Dotsinsky I, Mudrov T, Baldi A. Evaluation of Cisplatin as an electrochemotherapy agent for the treatment of incompletely excised mast cell tumors in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:407–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spugnini EP, Renaud SM, Buglioni S, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin enhances local control after surgical ablation of fibrosarcoma in cats: An approach to improve the therapeutic index of highly toxic chemotherapy drugs. J Transl Med. 2011;9:152. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spugnini EP, Baldi A, Vincenzi B, Bongiorni F, Bellelli C, Porrello A. Intraoperative versus postoperative electrochemotherapy in soft tissue sarcomas: A preliminary study in a spontaneous feline model. Cancer Chem Pharmacol. 2007;59:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spugnini EP, Vincenzi B, Betti G, et al. Surgery and electrochemotherapy of a high-grade soft tissue sarcoma in a dog. Vet Rec. 2008;162:186–168. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.6.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spugnini EP, Filipponi M, Romani L, et al. Electrochemotherapy treatment for bilateral pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:330–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spugnini EP, Dragonetti E, Vincenzi B, Onori N, Citro G, Baldi A. Pulse-mediated chemotherapy enhances local control and survival in a spontaneous canine model of primary mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000195702.73192.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spugnini EP, Vincenzi B, Citro G, et al. Electrochemotherapy for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in cats: A preliminary report. Vet J. 2009;179:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spugnini EP, Dotsinsky I, Mudrov N, et al. Electrochemotherapy-induced radiation recall in a cat. In Vivo. 2008;22:751–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook JL, Turk JR, Pope ER, Jordan RC. Infantile desmoid-type fibromatosis in an Akita puppy. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1998;34:291–294. doi: 10.5326/15473317-34-4-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper BJ, Valentine BA. Tumors of muscle. In: Meuten DJ, editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 4th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univ; Pr: 2002. pp. 319–363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutenberg MS, Indelicato DJ, Knapik JA, et al. External-beam radiotherapy for pediatric and young adult desmoid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:435–442. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longhi A, Errani C, Battaglia M, et al. Aggressive fibromatosis of the neck treated with a combination of chemotherapy and indomethacin. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90:E11–15. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]