Abstract

Ginseng has a long history of use for health enhancement, and there is some evidence from animal studies that it has a beneficial effect on cognitive performance. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of Korean red ginseng on cognitive performance in humans. A total of 15 healthy young males with no psychiatric or cognitive problems were selected based on an interview with a board-certified psychiatrist. The subjects were randomly assigned to receive a daily dose of 4,500 mg red ginseng or placebo for a 2-week trial. There were 8 subjects in the red ginseng group and 7 subjects in the placebo group. All of the subjects were analyzed with the Vienna test system and a P300 event-related potential (ERP) test. There were no significant differences in the Vienna test system scores between the red ginseng group and the placebo group. In the event-related potential test, the C3 latency of the red ginseng group tended to decrease during the study period (p=0.005). After 2 wk, significant decreases were observed in the P300 latencies at Cz (p=0.008), C3 (p=0.005), C4 (p=0.002), and C mean (p=0.003) in the red ginseng group. Our results suggest that the decreased latency in ERP is associated with improved cognitive function. Further studies with a higher dosage of ginseng, a larger sample size, and a longer follow-up period are necessary to confirm the clinical efficacy of Korean red ginseng.

Keywords: Panax ginseng, Cognitive and motor function, Evoked potentials, Korean red ginseng, Vienna test system

INTRODUCTION

Ginseng roots have been used for over 2,000 years in many Asian countries. Panax ginseng, the herbal root of P. ginseng Meyer, is also known as Korean ginseng. The various forms of ginseng are processed differently for different uses. White ginseng is air-dried, whereas red ginseng is produced by steaming and drying. It has been reported that red ginseng is pharmacologically more active than white ginseng [1]. The difference in the biological activity of red and white ginseng may result from the different chemical constituents produced during processing [1].

Ginseng has a complex activity profile that includes antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and immune- stimulatory properties [2]. Thus, ginseng has the effects of stabilizing and balancing the entire physiology.

The active components in ginseng include ginsenosides, polysaccharides, peptides, polyacetylenic alcohols, vitamins, minor elements and enzymes [2]. Ginsen-osides are found only in Panax species and are believed to be responsible for most of the activities of ginseng. Ginsenosides can be classified into three major groups based on the chemical structures of their saponins: the panaxadiol (Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Rg3, Rh2, and Rs1), panaxatriol (Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg2, and Rh1), and oleanolic acid groups (Ro). Among these, Rb1 and Rg1 play major roles in both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on the central nervous system, modulating neurotransmission. Rb1 is often used to represent the panaxadiol ginsenosides and Rg1 often represents the panaxatriol ginsenosides. Both Rb1 and Rg1 are thought to improve cognitive function [3,4]. Ginsenosides act through diverse mechanisms, and it has been suggested that each ginsenoside has its own tissue-specific effects [5]. Although there is a large body of work attesting to the cognition-enhancing effects of ginseng in animals, there is little evidence of such effects following the chronic administration of ginseng in humans.

Jin et al. [6] studied the effects of red ginseng extract on learning and memory impairments induced by scopolamine. Scopolamine increases acetylcholinesterase activity and reduces acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, resulting in impaired cognitive function. The red ginseng treatment group had improved Morris water maze test scores (reduced total swimming time) compared with the saline-treated group. This result suggests that red ginseng may be a cognitive enhancer. However, Lee et al. [7] also studied the cognition-enhancing effect of ginseng extracts using the Morris water maze test and did not find any direct evidence of a pharmacological mechanism through which ginseng therapy might improve cognitive function.

Korean red ginseng was shown in another study to significantly reduce the latency of the P300 component of an evoked potential [8]. This finding suggests that Korean red ginseng can directly modulate cerebro-electrical activity. Kennedy and Scholey [9] similarly suggested that ginseng may be a cognitive enhancer. However, further studies are needed to investigate which brain regions are affected by ginseng.

The current study used the P300 event-related potential (ERP) and the computerized neurocognitive function test (Vienna test system) to investigate the effect of Korean red ginseng on cognitive performance. First, we analyzed the P300 event-related potential [10] to confirm previous study findings that Korean red ginseng reduces P300 latency in the left temporal and occipital lobes, which is related to immediate memory and behavior reaction time. The P300 event-related potential is thought to reflect the neurophysiological activity related to cognitive processes, such as attention, discrimination, and working memory [11]. Second, we used a computerized neurocognitive function test (Vienna test system) [12] as an objective and accurate measure of the effects of Korean red ginseng on cognitive and fine motor functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 20 healthy young male volunteers aged 19 to 25 years were recruited through on-line and off-line advertisements for inclusion in this study. Prior to participation, each volunteer signed an informed consent form. Participants were interviewed by a board-certified psychiatrist to ensure that none of the participants had psychiatric disorders or cognitive problems. After assessment with the Annett handedness inventory [13], we identified 15 right-handed volunteers for inclusion in this study.

Procedure

The 15 subjects included in this study were randomly assigned to either the red ginseng group or the placebo group: 8 received red ginseng and 7 received a placebo over a 2-week period. The ginseng group was administered 1,500 mg ginseng three times per day for a total daily dose of 4,500 mg (1 tablet=300 mg). The ginsenosides, the active constituents of Korean red ginseng, were composed of Rb1 (1.96%), Rb2 (2.18%), Rc (1.47%), Rd (0.72%), Re (1.11%), Rf (0.24%), Rg1 (0.49%), Rg2 (0.13%), Rg3(0.12%), Rh1 (0.12%), and Rh2 (0.003%) and accounted for 8.54% of the herb. During the 2-week trial period, the subjects were instructed to refrain from taking medications and drinking excessive amounts of alcohol.

The P300 ERP [10] and computerized neurocognitive function test [11] were performed at baseline and repeated 2 wk later. The effects of red ginseng and the placebo on cognitive function were assessed by comparing the changes in the two groups over the trial period in the P300 ERP and Vienna test system scores.

Neurocognitive function test

The computerized neurocognitive function test (Vienna test system version IX) [12] was used to evaluate cognitive function. Descriptions of the test categories are as follows [14]:

Vigilance

The subject is presented with a large circle composed of small rings. A point travels along the circular path from one ring to the next. Occasionally, however, one ring is skipped and the point jumps to the next ring on the circle. When this occurs, the subject has to respond by pressing the central key on the test subject panel. This test, which takes approximately 25 min, evaluates the subject’s ability to sustain alertness after extended exposure to a low-level and monotonous stimulus.

Reaction unit

This test is designed to determine the reaction time in response to a visual stimulus. The subject places his or her hand on the rest button and is required to push it immediately whenever he or she detects a visual stimulus. The total testing time is 10 to 15 min.

Motor performance series

Several different fine motor skills of the left and right arms, hands and fingers are assessed by testing steadiness, aiming, tapping, and pegboard performance. In the current study, different subtests were applied using the commercially available ‘MLS’ of the Vienna test system, which consists of a standardized metal work top (300×300×15 mm) with holes and contact fields for the different subtests [15]. Two contact pencils are connected to the sides of the worktop. The number and duration of contacts between pencils and the test board are measured as closures in the electrical circuits (5 V, 20 mA). The data are transferred via an interface to a computer for analysis.

Event-related potential test

The P300 ERP [10] were obtained in a room free of noise and electrical fields. The subjects were seated in a comfortable armchair. The active electrode was attached to the vertex (Cz), reference electrodes were attached to A1 (A2), and the ground electrode was attached to the forehead (Fpz). The electrooculogram was recorded from electrodes placed above and below the outer corner of the right eye.

During the P300 recording, subjects were instructed to avoid excessive movement of the face, eyes, and neck. The subjects were cooperative, and few trials were rejected due to artifacts. In the ERP to target stimuli, P300 was identified as the highest positive component that appeared 250 to 500 ms after stimulation. Latency was calculated as the time required to obtain the P300 peak [12].

Statistical analysis

For comparison of the demographic variables between the two groups, an independent t-test was performed using SPSS ver. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Inter-group comparisons of changes in P300 ERP and computerized neurocognitive function test variables were assessed using a repeated measures ANOVA. All of the statistical analyses were two-tailed, and the level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in the Vienna test scores between the red ginseng group and the placebo group (Tables 1-3). However, in the ERP test, the C3 latency of the red ginseng group tended to decrease during the study period (Table 4). There were also significant decreases in the latencies of Cz (p=0.008), C3 (p=0.005), C4 (p=0.002), and C mean (p=0.003) in the red ginseng group.

Table 1.

Changes in Vienna test variables in reaction unit between red ginseng and placebo groups during the 2-week trial

| Reaction unit | Red ginseng | Placebo | Wilks Λ | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | 2 wk | Baseline | 2 wk | |||

|

| ||||||

| Median reaction time (msec) | 592.1 (101.2) | 544.8 (72.3) | 579.0 (92.9) | 604.2 (105.0) | 0.659 | 0.028 |

| Median decision time (msec) | 421.0 (63.5) | 392.6 (49.9) | 382.7 (64.8) | 417.2 (83.4) | 0.728 | 0.056 |

| Median motor time (msec) | 152.0 (25.1) | 145.1 (25.9) | 190.8 (44.3) | 173.2 (42.7) | 0.896 | 0.260 |

| Wrong decision | 0.13 (0.35) | 0.38 (0.52) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.50 (0.55) | 0.959 | 0.487 |

| Right reaction | 8.00 (0.00) | 7.88 (0.35) | 7.67 (0.52) | 7.83 (0.41) | 0.854 | 0.178 |

| Incomplete reaction | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.13 (0.35) | 0.17 (0.41) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.171 | 0.178 |

Values are given as mean (SD) scores.

Table 3.

Changes in Vienna test variables in motor performance series between red ginseng and placebo groups during the 2-week trial

| MPS | Red ginseng | Placebo | Wilks Λ | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Baseline | 2 wk | Baseline | 2 wk | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Right | Aiming error | 0.75 (1.17) | 1.50 (2.73) | 0.86 (0.90) | 0.57 (0.54) | 0.930 | 0.339 |

| Aiming H | 20.1 (0.4) | 20.3 (0.5) | 19.6 (0.8) | 20.0 (0.0) | 0.950 | 0.425 | |

| Aiming T | 6.57 (1.00) | 6.83 (1.04) | 6.41 (0.73) | 6.18 (0.75) | 0.855 | 0.161 | |

| Insertion long pins T | 37.2 (2.1) | 36.8 (4.2) | 40.6 (4.0) | 39.3 (3.9) | 0.988 | 0.698 | |

| Steadiness error | 1.00 (2.07) | 1.25 (1.04) | 3.71 (6.02) | 0.71 (1.11) | 0.874 | 0.194 | |

| Line tracking error | 18.0 (8.6) | 13.3 (6.0) | 18.9 (6.2) | 14.1 (5.7) | 1.0 | 0.993 | |

| Line tracking T | 27.6 (11.3) | 26.5 (8.9)5 | 26.3 (7.0) | 25.1 (13.5) | 1.0 | 0.984 | |

| Tapping H | 227.9 (23.4) | 225.5 (17.1) | 180.1 (37.7) | 191.6 (13.8) | 0.93 | 0.341 | |

| Inserting short pins T | 45.2 (5.9) | 47.3 (4.3) | 45.8 (5.4) | 52.4 (10.4) | 0.84 | 0.214 | |

| Left | Aiming error | 4.88 (5.22) | 3.00 (3.34) | 2.86 (2.27) | 4.14 (2.12) | 0.854 | 0.160 |

| Aiming H | 20.6 (1.5) | 20.1 (1.1) | 19.9 (0.4) | 19.7 (1.1) | 0.987 | 0.689 | |

| Aiming T | 9.59 (2.47) | 9.16 (1.65) | 8.18 (1.38) | 8.02 (1.93) | 0.992 | 0.758 | |

| Inserting long pins T | 44.1 (4.9) | 42.6 (6.2) | 43.4 (2.6) | 41.8 (5.0) | 1.0 | 0.963 | |

| Steadiness error | 1.38 (2.50) | 5.75 (9.30) | 0.71 (1.25) | 1.00 (1.92) | 0.862 | 0.173 | |

| Line tracking error | 26.4 (8.9) | 27.0 (5.3) | 28.4 (7.8) | 27.0 (5.3) | 0.983 | 0.643 | |

| Line tracking T | 26.3 (8.5) | 24.0 (6.5) | 24.8 (8.4) | 25.5 (12.8) | 0.953 | 0.436 | |

| Tapping H | 178.8 (28.6) | 175.8 (29.6) | 169.6 (33.8) | 182.3 (24.3) | 0.897 | 0.242 | |

| Inserting short pins T | 53.0 (11.3) | 55.0 (6.6) | 54.0 (5.4) | 51.3 (6.3) | 0.919 | 0.302 | |

| Both | Steadiness error (R) | 2.13 (4.85) | 0.88 (2.48) | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.57 (7.76) | 0.868 | 0.183 |

| Steadiness error (L) | 0.75 (1.17) | 0.63 (0.92) | 6.14 (15.4) | 2.86 (4.18) | 0.976 | 0.582 | |

| Inserting long pins T (R) | 57.5 (7.8) | 55.9 (6.0) | 62.0 (12.0) | 57.4 (6.1) | 0.962 | 0.487 | |

| Inserting long pins T (L) | 58.6 (8.9) | 56.5 (7.5) | 62.8 (11.7) | 58.5 (5.9) | 0.982 | 0.630 | |

| Aiming error (R) | 3.00 (2.93) | 2.13 (2.03) | 1.14 (1.68) | 1.00 (1.16) | 0.961 | 0.482 | |

| Aiming H (R) | 21.3 (1.0) | 20.3 (1.7) | 20.1 (1.2) | 20.0 (0.6) | 0.931 | 0.343 | |

| Aiming T (R) | 12.4 (3.8) | 12.3 (4.8) | 10.3 (1.5) | 9.8 (1.5) | 0.991 | 0.732 | |

| Aiming H (L) | 23.0 (4.9) | 20.9 (2.9) | 19.7 (1.6) | 18.3 (2.4) | 0.979 | 0.602 | |

| Aiming T (L) | 12.3 (3.6) | 13.0 (5.5) | 10.4 (1.6) | 9.8(1.6) | 0.925 | 0.324 | |

| Tapping H (R) | 188.1 (36.3) | 191.9 (33.1) | 172.4 (36.2) | 178.9 (27.5) | 0.991 | 0.734 | |

| Tapping H (L) | 174.9 (40.3) | 168.9 (22.9) | 173.7 (23.9) | 163.6 (32.6) | 0.985 | 0.668 | |

| Inserting short pins T (R) | 68.7 (15.8) | 66.9 (9.8) | 71.3 (11.9) | 75.2 (15.0) | 0.957 | 0.458 | |

| Inserting short pins T (L) | 68.4 (13.7) | 68.8 (9.5) | 73.7 (10.6) | 76.8 (15.2) | 0.988 | 0.703 | |

Values are given as mean (SD) scores.

H, number of hitting; T, time required for performance; R, right; L, left.

Table 4.

Changes in event-related potential test results between red ginseng and placebo groups during the 2-week trial

| Red ginseng | Placebo | Wilks Λ | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | 2 wk | Baseline | 2 wk | |||

|

| ||||||

| Frontal | ||||||

| Fz latency | 369.29 (14.19) | 365.71 (18.54) | 361.07 (11.79) | 357.14 (12.57) | 1.0 | 0.975 |

| Fz amplitude | 6.23 (5.43) | 10.64 (3.89) | 6.84 (4.34) | 7.68 (3.32) | 0.863 | 0.193 |

| F4 latency | 368.57 (10.51) | 367.5 (13.63) | 354.29 (11.16) | 358.21 (11.47) | 0.975 | 0.586 |

| F4 amplitude | 7.48 (4.64) | 11.51 (4.11) | 7.05 (4.78) | 9.83 (3.76) | 0.980 | 0.632 |

| F3 latency | 366.43 (12.16) | 361.79 (14.86) | 362.14 (10.39) | 362.59 (14.58) | 0.962 | 0.501 |

| F3 amplitude | 6.74 (5.77) | 11.07 (4.36) | 7.05 (3.99) | 7.64 (2.45) | 0.788 | 0.098 |

| Mean (F3, F4, Fz) latency | 368.09 (10.9) | 365 (14.48) | 359.17 (9.78) | 359.29 (8.57) | 0.978 | 0.612 |

| Mean (F3,F4,Fz) amplitude | 6.74 (5.77) | 11.07 (4.36) | 6.98 (4.53) | 8.38 (3.26) | 0.883 | 0.230 |

| Central | ||||||

| Cz latency | 372.50 (13.5) | 367.14 (15.32) | 363.57 (13.55) | 355.71 (9.97) | 0.992 | 0.762 |

| Cz amplitude | 10.38 (5.83) | 13.2 (4.67) | 11.06 (5.08) | 10.81 (4.74) | 0.888 | 0.242 |

| C3 latency | 374.29 (12.59) | 367.5 (16.42) | 359.29 (14.25) | 363.21 (11.7) | 0.674 | 0.033 |

| C3 amplitude | 9.69 (5.61) | 13.1 (4.45) | 10.36 (4.64) | 10.44 (3.66) | 0.854 | 0.156 |

| C4 latency | 372.14 (13.59) | 368.57 (14.87) | 362.5 (14.14) | 367.5 (14.14) | 0.925 | 0.344 |

| C4 amplitude | 11.57 (4.67) | 14.24 (5.23) | 9.86 (5.06) | 10.53 (3.54) | 0.939 | 0.396 |

| Mean (C3, C4, Cz) latency | 372.98 (14.19) | 367.79 (16.71) | 361.79 (10.38) | 362.14 (7.13) | 0.920 | 0.327 |

| Mean (C3, C4, Cz) amplitude | 10.55 (5.71) | 13.51 (5.09) | 10.43 (5.33) | 10.6 (4.22) | 0.891 | 0.250 |

| Parietal | ||||||

| Pz latency | 372.14 (14.17) | 358.57 (11.29) | 367.5 (11.34) | 356.43 (9.62) | 0.998 | 0.888 |

| Pz amplitude | 14.21 (4.97) | 15.61 (6.13) | 11.73 (4.97) | 12.36 (4.49) | 0.994 | 0.801 |

| P3 latency | 372.14 (13.12) | 368.21 (9.79) | 367.14 (16.06) | 358.93 (8.22) | 0.987 | 0.697 |

| P3 amplitude | 13.44 (4.75) | 14.46 (4.47) | 11.60 (5.26) | 12.28 (3.32) | 0.999 | 0.897 |

| P4 latency | 370.36 (14.36) | 372.14 (10.3) | 365,36 (12.85) | 360 (12.89) | 0.966 | 0.526 |

| P4 amplitude | 13.51 (3.72) | 14.51 (6.71) | 510.31 (5.12) | 11.54 (3.98) | 0.999 | 0.938 |

| Mean (P3, P4, Pz) latency | 371.58 (14.89) | 366.31 (13.74) | 366.67 (11.93) | 358.45 (9.11) | 0.992 | 0.768 |

| Mean (C3, C4, Cz) amplitude | 13.72 (4.75) | 14.86 (6.14) | 11.21 (5.43) | 12.06 (4.18) | 0.999 | 0.919 |

Table 2.

Changes in Vienna test variables in vigilance between red ginseng and placebo groups during the 2-week trial

| Vigilance | Red ginseng | Placebo | Wilks Λ | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | 2 wk | Baseline | 2 wk | |||

|

| ||||||

| No. of correct | 99.3 (1.0) | 92.1 (17.9) | 98.7 (1.7) | 97.3 (2.9) | 0.949 | 0.416 |

| Mean value of reaction time (s) | 0.45 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.12) | 0.53 (0.14) | 0.965 | 0.507 |

| No. of incorrect | 0.50 (1.41) | 1.13 (2.80) | 1.00 (0.58) | 0.71 (1.11) | 0.873 | 0.192 |

| No. of missed | 0.71 (1.11) | 1.57 (1.40) | 1.29 (1.70) | 2.71 (2.87) | 0.966 | 0.529 |

Values are given as mean (SD) scores.

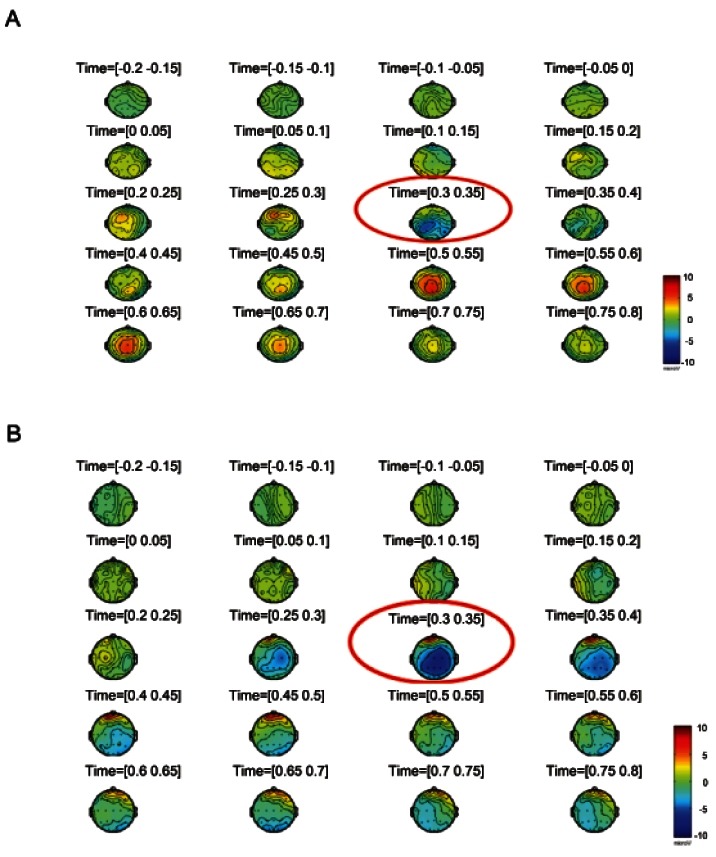

In addition, the red ginseng group showed a greater decrease in P300 voltage difference from baseline compared with the placebo group (Fig. 1) (at time=[0.30-0.35], red circle) according to brain mapping.

Fig. 1. Voltage difference between red ginseng and placebo group at baseline (A) and after 2 wk (B). The red ginseng group showed a greater-decreased in P300 voltage difference from baseline compared with that of the placebo group during 2-week trial period (at time=[0.30-0.35], red circle), according to brain mapping.

DISCUSSION

In our study, the red ginseng group showed a decreased latency of P300 in the central area (Cz, C3, C4, and C mean) compared with baseline using a paired t-test. Although efficacy in animals does not guarantee efficacy in humans, our results are consistent with previous findings that Korean red ginseng decreases the latency of P300 in animal tests [8,9,16].

The P300 component of ERP is used as a marker of cognitive function and is related to the decision-making process [17]. The P300 amplitude is thought to be an index for brain activity [18] and can be viewed as a measure of central nervous system activity that processes incoming information into memory representations of the stimulus and its context. The P300 amplitude, therefore, is assumed to reflect the degree or quality with which that information is processed.

P300 latency is considered to be a measure of stimulus classification speed and is generally unrelated to response selection processes. It is, therefore, independent of behavioral reaction time. These properties make the P300 a valuable tool for assessing cognitive function. Because P300 latency is an index of the processing time required before response generation, it is a sensitive temporal measure of the neural activity underlying the processes of attention allocation and immediate memory. In addition, P300 latency is negatively correlated with mental function in normal subjects, with shorter latencies and amplitudes associated with superior cognitive performance [19]. Kennedy and Scholey [9] found that red ginseng decreased the P300 latency in the left temporal and occipital lobes. However, our study found that Korean red ginseng decreased the latency of P300 in the central area.

Further studies are necessary to investigate which brain regions are affected by Korean red ginseng.

Our results support only one of our hypotheses, which is that Korean red ginseng decreases P300 latency related to cognitive function, but not our other hypothesis that it would improve Vienna test scores of fine motor performance. Several possible explanations can be proposed for this unexpected finding. One explanation is that improvement in fine motor performance may not be associated with decreased P300 latency. Another possible explanation is that for the distinctive efficacy of fine motor movement, a longer trial of red ginseng is needed to observe improvements.

The most prominent ERP components widely observed in studies of cognitive function are N100, P200, P300, and N200. The expectancy of motor response has been suggested to be a major factor modulating scalp-recorded P300. Verleger et al. [20] performed a Go/NoGo test to explore the motor-related activation of cognitive function measured with P300 and N200. The study confirmed that the N200 and P300 effects were not solely due to movement-related potentials and suggested P300 as a marker of motor inhibition. Thus, further studies are needed to measure other ERP components to confirm the efficacy of Korean red ginseng for fine motor performance.

Wesnes et al. [21] performed a 12-week ginseng trial with 256 healthy middle-aged volunteers and used the computerized cognitive assessment system to study the effects of ginseng treatment. In their study, the ginseng group demonstrated improved memory, including working and long-term memory. A few studies have identified cholinergic properties associated with single ginsenosides, such as a direct interaction between Rg2 and nicotinic receptor subtypes [22], the modulation of acetylcholine release and reuptake by Rb1, and the number of choline uptake sites in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is located in the temporal lobe and plays important roles in the consolidation of information from short-term to long-term memory. The ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 have also been shown to increase choline acetyltransferase levels in rodent brains, which may contribute to cognitive function enhancement in such areas as working and long-term memory [23].

The exact mechanism through which ginseng enhances cognitive function is still unknown, but one report has indicated that ginseng might improve cognitive function by modulating neurotransmission. Petkov [24] found that ginseng administration (50 mg/kg) led to increased dopamine and norepinephrine in the brainstem and increased serotonin in the cortex. This effect was abolished by the administration of either a serotonin receptor agonist or a specific serotonin antagonist, suggesting that serotonergic transmission is involved in the memory-enhancing effect of ginseng. Wang et al. [25] also found that both root and stem/leaf saponins improved learning and increased the levels of biogenic monoamines in normal rat brains. These effects are thought to be necessary changes of neuroplasticity at the synapse level, which may require several months. Although the mechanism of behavior reaction time is not the same as memory function, improvements in reaction time may require long-term ginseng administration. This hypothesis suggests that our study trial of two weeks may have been too short to observe any effect from the ginseng treatment.

There are some limitations to our study. First, the sample size was too small (n=15), and the trial duration was too short (2 wk). Second, in the experimental design, we could not control for the practice effect on our measurements using the computerized neurocognitive function test. Third, the dosage of ginseng may have been inadequate. The recommended daily dose of ginseng for humans is 1.5 to 3.0 g/d [26], whereas Heo et al. [27] used ginseng doses up to 9.0 g/d to show improved cognitive function. The dosage we used in this study may have been too low to produce an effect. Fourth, because of the small sample size, our data were analyzed using nonparametric statistics.

In conclusion, subjects who received Korean red ginseng showed a decreased latency of P300 in the central region (Cz, C3, C4, and C mean). However, there were no significant changes in Vienna test scores between the red ginseng group and the placebo group after 2 wk. The observed decreased latency in ERP may indicate an improvement in cognitive function, especially in association with attention allocation, immediate memory and behavior reaction time. Our findings warrant further study with a higher ginseng dose, a larger sample size, and a longer follow-up period to confirm the clinical efficacy of Korean red ginseng.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the 2008 grant from The Korean Society of Ginseng.

References

- 1.Baek NI, Kim DS, Lee YH, Park JD, Lee CB, Kim SI. Ginsenoside Rh4, a genuine dammarane glycoside from Korean red ginseng. Planta Med. 1996;62:86–87. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang YZ, Shang HC, Gao XM, Zhang BL. A comparison of the ancient use of ginseng in traditional Chinese medicine with modern pharmacological experiments and clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2008;22:851–858. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heo JH, Kim MH. The efficacy of ginseng on the cognitive function. J Ginseng Res. 2009;33:161–164. doi: 10.5142/JGR.2009.33.3.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TW, Choi HJ, Kim NJ, Kim DH. Anxiolytic-like effects of ginsenosides Rg3 and Rh2 from red ginseng in the elevated plus-maze model. Planta Med. 2009;75:836–839. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy LL, Lee TJ. Ginseng, sex behavior, and nitric oxide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin SH, Park JK, Nam KY, Park SN, Jung NP. Korean red ginseng saponins with low ratios of protopanaxadiol and protopanaxatriol saponin improve scopolamine-induced learning disability and spatial working memory in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;66:123–129. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MR, Sun BS, Gu LJ, Wang CY, CY EK, Yang SA, Lee SY, Sung CG. Effects of white ginseng and red ginseng extract on learning performance and acetylcholinesterase activity inhibition. J Ginseng Res. 2008;32:341–346. doi: 10.5142/JGR.2008.32.4.341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB, Drewery L, Marsh VR, Moore B, Ashton H. Electroencephalograph effects of single doses of Ginkgo biloba and Panax ginseng in healthy young volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:701–709. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB. Ginseng: potential for the enhancement of cognitive performance and mood. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:687–700. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DB, Donchin E, Cohen L, Starr A. Auditory averaged evoked potentials in man during selective binaural listening. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1970;28:146–152. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(70)90182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polich J, Kok A. Cognitive and biological determinants of P300: an integrative review. Biol Psychol. 1995;41:103–146. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(95)05130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuhfried G. The PC/S vienna test system: test management program. Schuhfried GmbH; Modling: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annett M. The binomial distribution of right, mixed and left handedness. Q J Exp Psychol. 1967;19:327–333. doi: 10.1080/14640746708400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwenkreis P, El Tom S, Ragert P, Pleger B, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Assessment of sensorimotor cortical representation asymmetries and motor skills in violin players. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3291–3302. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalisch T, Wilimzig C, Kleibel N, Tegenthoff M, Dinse HR. Age-related attenuation of dominant hand superiority. PLoS One. 2006;1:e90. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB, Wesnes KA. Modulation of cognition and mood following administration of single doses of Ginkgo biloba, ginseng, and a ginkgo/ginseng combination to healthy young adults. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:739–751. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polich J, Herbst KL. P300 as a clinical assay: rationale, evaluation, and findings. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;38:3–19. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donchin E, Karis D, Bashore TR, Coles MG, Gratton G. Cognitive psychophysiology and human information processing. In: Cole MG, Donchin E, Porges SW. ed. Psychophysiology: systems, processes, and applications. Guilford Press; New York: 1986. pp. 244–267. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmerson RY, Dustman RE, Shearer DE, Turner CW. P3 latency and symbol digit performance correlations in aging. Exp Aging Res. 1989;15:151–159. doi: 10.1080/03610738908259769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verleger R, Paehge T, Kolev V, Yordanova J, Jaskowski P. On the relation of movement-related potentials to the go/ no-go effect on P3. Biol Psychol. 2006;73:298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wesnes KA, Ward T, McGinty A, Petrini O. The memory enhancing effects of a Ginkgo biloba/Panax ginseng combination in healthy middle-aged volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s002130000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sala F, Mulet J, Choi S, Jung SY, Nah SY, Rhim H, Valor LM, Criado M, Sala S. Effects of ginsenoside Rg2 on human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:1052–1059. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang JT, Qu ZW, Liu Y, Deng HL. Preliminary study on antiamnestic mechanism of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1. Chin Med J (Engl) 1990;103:932–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petkov V. Effect of ginseng on the brain biogenic monoamines and 3’,5’-AMP system. Experiments on rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1978;28:388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang A, Cao Y, Wang Y, Zhao R, Liu C. Effects of Chinese ginseng root and stem-leaf saponins on learning, memory and biogenic monoamines of brain in rats. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1995;20:493–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin YR, Yu JY, Lee JJ, You SH, Chung JH, Noh JY, Im JH, Han XH, Kim TJ, Shin KS, et al. Antithrombotic and antiplatelet activities of Korean red ginseng extract. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;100:170–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heo JH, Lee ST, Chu K, Oh MJ, Park HJ, Shim JY, Kim M. An open-label trial of Korean red ginseng as an adjuvant treatment for cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:865–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]