Abstract

Endogenous stem cells in the bone marrow respond to environmental cues and contribute to tissue maintenance and repair. In type 2 diabetes, a multifaceted metabolic disease characterized by insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, major complications are seen in multiple organ systems. To evaluate the effects of this disease on the endogenous stem cell population, we used a type 2 diabetic mouse model (db/db), which recapitulates these diabetic phenotypes. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from db/db mice were characterized in vitro using flow cytometric cell population analysis, differentiation, gene expression, and proliferation assays. Diabetic MSCs were evaluated for their therapeutic potential in vivo using an excisional splint wound model in both nondiabetic wild-type and diabetic mice. Diabetic animals possessed fewer MSCs, which were proliferation and survival impaired in vitro. Examination of the recruitment response of stem and progenitor cells after wounding revealed that significantly fewer endogenous MSCs homed to the site of injury in diabetic subjects. Although direct engraftment of healthy MSCs accelerated wound closure in both healthy and diabetic subjects, diabetic MSC engraftment produced limited improvement in the diabetic subjects and could not produce the same therapeutic outcomes as in their nondiabetic counterparts in vivo. Our data reveal stem cell impairment as a major complication of type 2 diabetes in mice and suggest that the disease may stably alter endogenous MSCs. These results have implications for the efficiency of autologous therapies in diabetic patients and identify endogenous MSCs as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: Diabetes, Autologous stem cell therapy, Mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Diabetes is a global epidemic with devastating comorbidities and complications, such as cardiovascular disease, neuropathy, infections, and impaired wound healing [1]. More than 90% of the diabetic human population suffers from type 2 diabetes. Although it is difficult to recapitulate the complex and multifactorial nature of type 2 diabetes, animal models provide a standardized measure that is not readily available in humans. Because of the full development of relevant complications, the most commonly implemented type 2 diabetic animal model is the BKS.Cg-Dock7m+/+Leprdb/J mouse (db/db). These animals exhibit hyperglycemia, obesity, insulin resistance, β-cell depletion, and all the diabetes-associated comorbidities, including impaired wound healing [2].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), a subpopulation of stromal cells throughout the body, contribute to tissue repair and have been used as a therapeutic tool [3, 4]. Currently, numerous clinical trials are exploring autologous MSC therapies in chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and liver cirrhosis [5]. MSCs are attractive agents for exogenous therapeutic delivery for chronic diseases because of their capacity for self-renewal, multipotentiality, and immune system modulation [6, 7]. Therapeutic MSC engraftment stimulates healing through the recruitment of host cells to the area of injury through cytokines and other paracrine factors [7, 8]. However, the pathophysiology of diseases such as type 2 diabetes may present challenges for the derivation or the therapeutic utility of autologous MSC therapies. Impaired mobilization and a reduction of the number of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in type 2 diabetic patients prevent vasculogenesis and impair healing [9–11]. Cells critical to wound healing, such as fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages, become functionally impaired when exposed to a diabetic-high glucose environment in vitro [12–15]. Although autologous therapies are deemed the safest approach to cellular therapy, the evaluation of diabetic cells is essential to developing efficient clinical therapies.

As the regenerative capacity of stem cells from a diabetic background has not been determined, we evaluated the bone marrow-derived MSC population in type 2 diabetic mice and assessed both their number and their functional capacity in culture and in a regenerative model of wound repair. The severe healing deficits in the db/db animals permit study of the regenerative capacity of bone marrow-derived MSCs engrafted in cutaneous wounds. Surprisingly, we found that diabetic MSCs were not equivalent to healthy MSCs. We identified three fundamental deficiencies in db/db animals: (a) there are fewer MSCs available with or without wounding, (b) diabetic MSCs (dbMSCs) available are proliferation and survival impaired, and (c) dbMSCs have significantly reduced regenerative capacity. In addition, signaling profiles in a db/db wound differed from those in a healthy wound. The combination of our in vitro and in vivo data suggests that diabetic subjects not only are impaired in their glucose metabolism but also exhibit severe deficits in their MSC populations. We propose that the pathophysiology of a chronic disease, such as type 2 diabetes, can cause severe MSC impairment, with subsequent complications throughout the body.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Eight-week-old BKS.Cg-Dock7m+/+Leprdb/J (db/db) male mice selected from a spontaneous diabetes mutation in the leptin receptor gene (Leprdb) and age-matched wild-type C57BLKS (WT) male mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, http://www.jax.org). Animals were equilibrated to the animal facility prior to any surgical procedures in cages of five and were housed individually postwounding. The weight and plasma glucose levels were recorded weekly on the nonwounded animals from nicked tail vein blood at 9:00 a.m. using an Accu-Chek glucose meter (Roche Group, Indianapolis, IN, http://www.roche-diagnostics.us). The weight and plasma glucose levels of the designated wounded animals were recorded immediately postwounding and at closure. All animal experiments and procedures have been reviewed and approved by the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation and Expansion of Mouse MSCs

We optimized culture conditions to ensure the greatest yield of mouse mesenchymal stem cells (mMSCs) as described previously [16]. mMSCs were extracted from the bone marrow of the tibiae and femurs of 8-week-old WT and db/db male mice by flushing the aspirates with an 18-gauge needle filled with Complete Expansion Media (CEM contains α-MEM, l-glutamine, Pen-Strep, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com; 20% serum, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, http://www.atlantabio.com). Aspirates were plated in CEM on 175-cm2 flasks and kept at 37°C in 5% CO2. Nonadherent cells were washed off, and adherent cells were expanded at a low plating density of 50 cells per cm2 flask for subsequent passages in 175-cm2 flasks. Viable cells were confirmed with 0.4% trypan blue assay. CEM was changed every 48 hours. MSCs were passaged at 80% confluence by dissociation with trypsin and EDTA. The total number of cells at each passage was recorded. Dissociated cells were then replated in new flasks at the same density (50 cells per cm2) at each subsequent passage, and remaining cells were frozen in CEM and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) for later use. Flask numbers varied after each passage, and a set number of cells were frozen using a seed lot system after each passage to ensure early passage material for future experiments. Vials designated as seed material were maintained separately from the working stocks to ensure that they remained unused. Measuring the dose/response to MSC engraftment, we determined that 100,000 cells was the minimal number of cells necessary to stimulate a healing response in both animals. Cells at ≤80% confluence at passage 4 were prepared for grafting to wound beds by dissociation, washing, and resuspension of 1 × 106 cells in 60 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for wound engraftment. We determined that at this passage, a homogeneous population of dbMSCs was present and had the greatest viability and proliferative capacity. Differentiation and colony-forming unit assays were performed on all MSC populations used in this study in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the International Society for Cellular Therapy-MSC Committee [11].

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cultured MSCs and wound bed tissue were dissociated into a single-cell suspension with trituration and collagenase digestion buffer (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ, http://www.worthington-biochem.com). Minced tissue was placed in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA overnight at 37°C and filtered through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com). To detect endogenous MSCs, dissociated cells were incubated with antibodies for positive MSC markers CD29 (β-1 integrin; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, http://www.abcam.com), CD44 (Indian blood group; Abcam), CD90 (cell surface glycoprotein marker Thy1; Invitrogen), and CD166 (ALCAM; Biolegend, San Diego, CA, http://www.biolegend.com). Other non-MSC populations and endothelial progenitor cells were identified using hematopoietic lineage markers CD45 (LCA; Abcam), CD34 (hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen; Invitrogen), CD31 (PECAM1; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, http://www.rndsystems.com), and CD14 (lipopolysaccharide receptor; R&D Systems). All conjugated pairs were incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes. Samples of 10,000 events were analyzed using the LSR II Flow Cytometer with the FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, San Diego, http://www.bdbiosciences.com).

Proliferation Studies

To quantify the number of proliferating cells and surviving cells between the two animal groups, 100,000 MSCs from both db/db and WT mice were labeled with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma-Aldrich) and Sytox Green (Invitrogen) to evaluate proliferation and survival. MSCs from both db/db and WT mice were plated in each well of a six-well plate for 2 days or until adherent in CEM. Medium was then replaced with 10 μM BrdU-supplemented CEM for 2 hours. The control well was designated as CEM only. BrdU-supplemented medium was rinsed off, and cells underwent a PBS wash. Cells were then fixed with Carnoy's fixative (Invitrogen) and labeled with anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY, http://www.accuratechemical.com) for labeling. Sytox Green was used as a counterstain to identify and quantify the total number of cells in each well.

Excisional Splint Wound Model

To examine the therapeutic capacity of dbMSCs on wound repair, 8-week-old db/db and age-matched wild-type male mice each received an excisional splint wound. This wound model closely mimics the physiologic process of wound healing in human subjects by preventing contraction and allowing the formation of granulation tissue [2, 17]. For surgical procedures, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (200 and 10 mg/kg, respectively), and then dorsal skin was shaved, depilated, and sterilized with ethanol. A full-thickness wound using an 8-mm Miltex (Plainsboro, NJ, http://miltex.com) dermal punch was created on the midback of all animals. A donut-shaped silicone splint (Grace Bio-labs, Bend, OR, http://www.gracebio.com) was centered over the wound and adhered with simple interrupted sutures and adhesive glue. Wounds received four intradermal injections of 100,000 mMSCs in PBS or 60 μl of PBS using a Hamilton syringe. Wounds were covered with Tegaderm dressing (3M, St. Paul, MN, http://www.3m.com), and animals were housed individually. Wound beds started at 50.24 mm2 and were monitored daily and documented by macroscopic examination using an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, http://www.olympus-global.com) equipped with a digital camera. The surgical dressing was removed and reapplied before and after each measurement. Digital images were acquired at fixed zoom settings and calibrated against a stage micrometer. Wound closure was quantified using the Cavalieri point probe estimator (StereoInvestigator software; MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, http://www.mbfbioscience.com) to accurately account for irregular and discontinuous profiles of healing tissue within the wound bed.

Immunohistochemistry

mMSCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours. The tissue was then processed through blocking steps using 0.25% Triton-X, primary antibody incubation at 1:500 using stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) (Millipore, Billerica, MA, http://www.millipore.com) or 1:1,000 CD44 (Invitrogen) for 12 hours at 4°C, rinse/blocking steps, followed by incubation with Cy3 or Cy2 fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. All secondary antibodies used in the laboratory were raised in donkey (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, http://www.jacksonimmuno.com). Sections were coverslipped in PVA-DABCO. Wounds and MSCs were imaged on an Olympus IX70 fluorescence microscope.

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

For Total RNA isolation and reverse-transcription, total RNA from tissue biopsies was extracted using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, http://www1.qiagen.com). Sample lysis and homogenization were achieved with sterile hard tissue omni probes (Omni International), followed by a proteinase-K digestion. The sample was treated with ethanol and applied to an RNeasy spin column. Purified total RNA was eluted in 60 μl of RNase-free water. RNA was run again through another RNeasy spin column as directed in the Qiagen RNA cleanup protocol to meet the RNA quality required for successful array runs. Purified RNA was placed in a speed vacuum to increase RNA concentration.

Known starting amounts of the isolated total RNA were used for reverse transcription (RT) reactions using the Improm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, http://www.promega.com) containing templates for first-strand cDNA synthesis of total RNA using oligo(dT)15 primers. Quantification of target genes was performed from known amounts of generated cDNA using a Bio-Rad iCycler Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, http://www.bio-rad.com). We used Bio-Rad SYBR Green supermix containing nucleotides, MgCl2, Taq polymerase, fluorescein, and SYBR Green. The cDNA was added to the supermix solution, forward and reverse primers, and RNase-free water to a volume of 25 μl per well in a 96-well plate. A 1:5 standard curve was run with all experimental samples, and all samples were run in triplicate. The standard cDNA was produced in-house from mouse MSCs generated from cell culture. A melt curve to check for SYBR Green specificity was also included. Negative controls included a sample collection negative control, a no-RT negative control, and a no-template control. Two factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Wnt3a, were selected for analysis. VEGF can promote mobilization of bone marrow-derived cells, increase cellular permeability, promote angiogenesis, and decrease apoptosis [18, 19]. Dysfunction of VEGF in diabetic wounds contributes to poor wound healing and remodeling [6]. Wnt3a is vital to MSC function and promotes proliferation, differentiation, and migration [20]. Mouse-specific primers were designed in-house using Beacon Designer software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, http://www.premierbiosoft.com) and synthesized by Operon (Huntsville, AL, http://www.operon.com). VEGF forward (5′-GGCTTACCCTTCCTCATCTTCCC-3′) and Wnt3a forward (5′-TTCCTGAGCGAGCCTGGGCT-3′) were used for our studies. Results were analyzed in comparison with a GAPDH housekeeping gene validated to have the lowest intersample variance.

Statistical Analysis

Between-group data comparisons were analyzed using analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test using the statistical software Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, http://www.graphpad.com). In cases where pairwise comparisons were designed, a Student's t test was used to ascertain significance. Significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Variance estimates encountered in generating the preliminary data revealed that most forms of analysis required a minimum sample size of six subjects per group. To ensure adequate inclusion in this study, experiments were designed with no fewer than 10 subjects per group.

Results

db/db Mice Exhibit Type 2 Diabetic Phenotypes and Associated Comorbidities

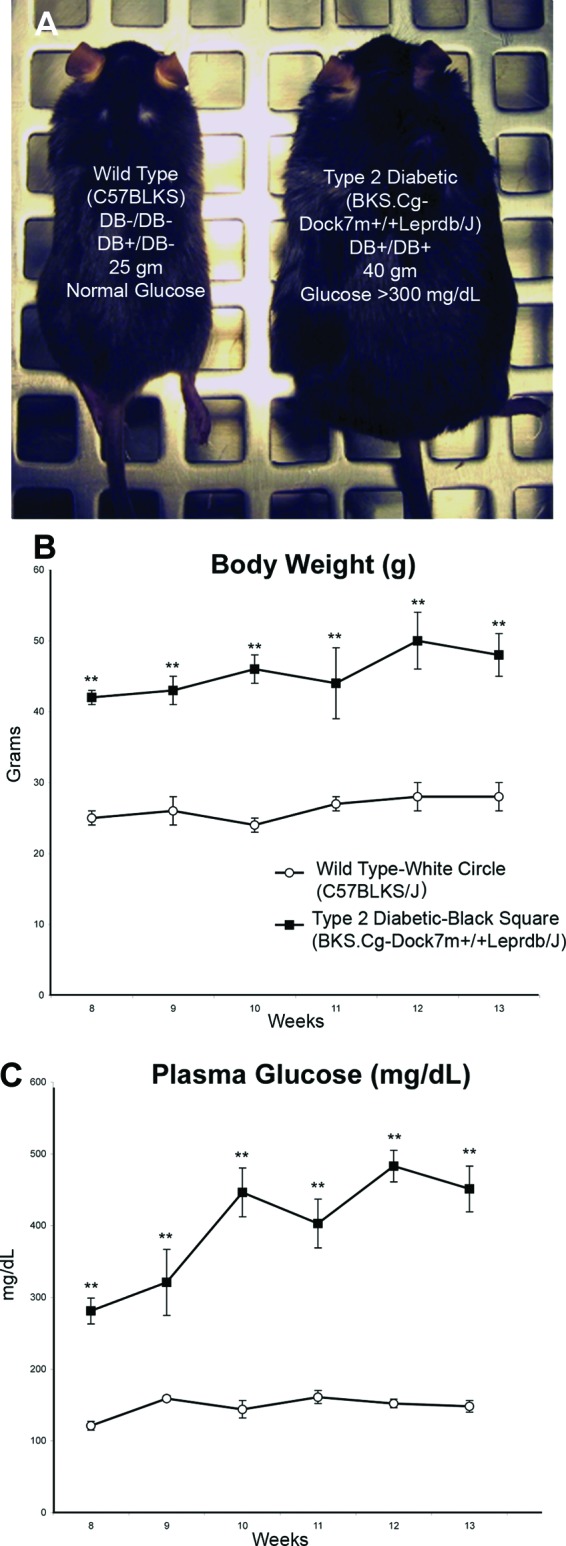

The db/db mouse (Jackson Laboratory) exhibits obesity (Fig. 1A, 1B), hyperglycemia (Fig. 1C), insulin resistance, and other phenotypes that are physiologically relevant to type 2 diabetes [21]. These animals were obese (42 ± 1 g) and experienced elevated blood sugar levels (281 ± 18 mg/dl) by 8 weeks (Fig. 1B, 1C). Mice with the same background strain that were heterozygous or negative for this mutation were metabolically normal and were used as a nondiabetic healthy control (WT). The db/db mice were polyphagic, polydipsic, and polyuric. These animals also exhibited retinopathy, cardiovascular disease, pancreatic β-cell depletion, neuropathy, nephropathy, obesity, and impaired wound healing (Jackson Laboratory). We evaluated the animals through week 13 and found that db/db mice maintained elevated blood sugar levels (451 ± 32 mg/dl), high body weight (48 ± 3 g), and low activity in comparison with their nondiabetic counterparts throughout this entire time period.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic characterization of diabetic and nondiabetic mice. (A): Age-matched 8-week-old nondiabetic (left; wild-type C57BLKS) and db/db (right; BKS.Cg-Dock7m +/+ Leprdb/J) mice are shown. The db/db mice exhibited hyperglycemia and obesity. Evaluation of the phenotype was completed using weight recordings (B) and plasma glucose levels (C) (both taken weekly at the same time), from wild-type and db/db mice using the tail vein blood. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group; **, p < .001).

db/db Mice Have Fewer MSCs than Their Nondiabetic Counterparts

To evaluate the impact of the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes on MSC number and function, we isolated total bone marrow from db/db and WT mice and plated these cells in a normal glucose environment in vitro. Bone marrow aspirates were evaluated preplating and after each passage in vitro. At earlier passages, bone marrow from db/db animals was more heterogeneous and contained fewer MSCs as a percentage of total cells (40%) than that of the WT animals (69%; Fig. 2A). Adherent bone marrow cells were characterized, and by passage 3, only a homogenous population of both dbMSCs (95.8%; Fig. 2A) and wild-type MSCs (wtMSCs) (98.3%; Fig. 2A) remained.

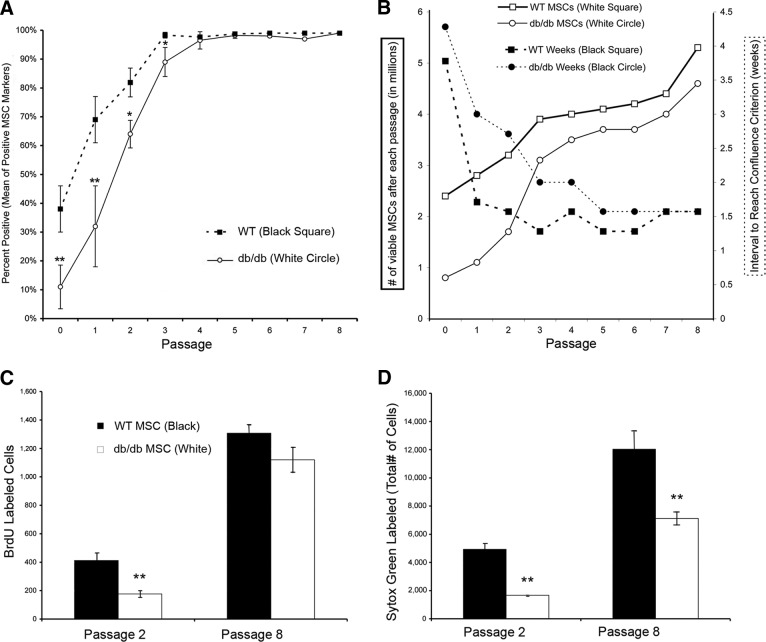

Figure 2.

Population analysis of endogenous MSCs in vitro. (A): MSCs were evaluated using flow cytometric analysis of the total number of diabetic (db) MSCs and wild-type (wt) MSCs with positive MSC markers CD29, CD44, CD90, and CD166 from passage 0 to passage 8. Each data point represents the pooled mean of the percentage of positively labeled MSCs markers. All positively labeled MSCs were negative for hematopoietic lineage-restricted markers CD14, CD34, and CD45. All mouse MSCs were derived in-house from db/db (n = 10) and WT (n = 10) mice. (B): The total number of cells and the time to reach a level of confluence appropriate for passaging (80% confluence) after each passage were recorded. A trypan blue exclusion assay was implemented to quantify viable cells. Each data point represents the total number of cells (solid lines, open symbols) and the number of weeks between passages (dashed lines, filled symbols). At early passages, dbMSCs had a lower proportion of viable cells and required longer to reach confluence. However, with time in standard culture conditions, the performance of the remaining dbMSCs largely matched that of wtMSCs. Assessment of MSC proliferation and survival revealed decreased efficiency of dbMSCs. (C): Proliferation and survival were assessed at passages 2 and 8 with BrdU. Proliferation of dbMSCs was significantly impaired at passage 2 compared with wtMSCs. However, by passage 8, dbMSCs increased to levels of WT proliferation (*, p < .05; **, p < .001). (D): Cultures at passages 2 and 8 were incubated with the nucleic acid marker Sytox Green, and the total number of cells in the same well was quantified. At both passage 2 and passage 8, dbMSCs had significantly fewer surviving cells despite an improvement in cell survival over time. Each column represents the total number of counted cells (error bars indicate ±SEM); n = 6 wells per group (**, p < .001). Abbreviations: BrdU, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; WT, wild-type.

dbMSCs Exhibit a Lag in Expanding Populations of Viable Cells

We documented the time required to reach appropriate confluence for passaging and the number of viable cells after each passage. At passage 1, freshly derived dbMSCs needed double the amount of time (3 weeks) to reach confluence compared with wtMSCs (Fig. 2B). The expansion of dbMSCs subsequently improved so that by passage 4, dbMSCs reached confluence in 2 weeks compared with 1.5 weeks for wtMSCs. Despite this lag, dbMSCs retained multipotency throughout multiple passages (supplemental information Fig. 1). Although initial viability of the dbMSCs were poor, over multiple passages in culture the number of viable cells approached the level seen in the wtMSCs (Fig. 2B).

dbMSC Proliferation Improves In Vitro over Time, but Cell Survival Is Still Impaired

To evaluate the viability and proliferative capacity of dbMSCs in culture, cell population kinetics were assessed directly. As a separate assay, equivalent numbers of dbMSCs and wtMSCs were plated to evaluate the total number of surviving cells and the total number of proliferating cells after initial culturing (passage 2) and after multiple passages in culture (passage 8; Fig. 2C, 2D). Initially, the number of proliferating (BrdU labeled) dbMSCs (176 ± 60) was significantly lower (**, p < .001) than the number of wtMSCs (412 ± 51) at passage 2 (Fig. 2C). By passage 8, however, this difference disappeared, and the number of proliferating dbMSCs (1,119 ± 88) increased sixfold, reaching the level of wtMSC proliferation (1,307 ± 24), which increased only threefold over the same period (Fig. 2C). In contrast, dbMSCs were significantly impaired in cell survival over the entire period in culture compared with wtMSCs, despite their improved ratio of proliferating cells to surviving population (from 10% to 16% at passage 8; Fig. 2D). This impairment in proliferation and survival explains the lag seen in the dbMSC population expansion at earlier time points. The subpopulation of proliferating dbMSCs emerging at later time points increased the number of viable cells and reduced the time between passages. Although this enrichment in culture compensated for poorer survival, it still could not close the inherent physiologic gap between dbMSCs and wtMSCs.

dbMSCs Show Altered Gene Expression Even After Selection

MSCs play a role in tissue repair through signal transduction. We compared naïve wound beds at 5 days postwounding using a customized polymerase chain reaction (PCR) array designed for MSC, inflammatory, and wound healing related markers. We found expression deficits in proliferative (epidermal growth factor), angiogenic (TBX1, TBX5), and differentiation (Fzd9) signaling factors and increased expression of inflammatory (interleukin [IL]-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, CXCL2) and apoptotic (IL-1B) factors in the db/db wound (supplemental information Fig. 2; supplemental information Table 1). These alterations in signaling were also consistent with delays in wound closure. We then evaluated the levels of expression of proangiogenic factor VEGF and proliferative factor Wnt3a in dbMSCs in cultures.

Table 1.

Area of wound closure in an excisional splint wound model after PBS or MSC engraftment

aWound beds were monitored daily, and measurements were taken daily. Data are expressed as mm2 ± SEM. Total area of wound at start was 50.24 mm2 (n=10 per group).

bp < 0.001 (PBS vs. wtMSC).

cp < 0.001 (wtMSC vs. dbMSC).

dp < 0.05 (wtMSC vs. dbMSC).

ep < 0.05 (PBS vs. dbMSC).

Abbreviations: DB, diabetic; dbMSC, diabetic mesenchymal stem cell; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild-type; wtMSC, wild-type mesenchymal stem cell.

RNA extracted from cultured WT and dbMSCs at passage 4 was used for RT-PCR analysis. After enrichment in culture, dbMSCs showed levels of VEGF expression similar to those of their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 3). However, dbMSCs showed significantly decreased levels (*, p < .05) of Wnt3a expression at the same time point (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of endogenous MSCs in vitro. WT and dbMSCs were analyzed at passage 4 for gene expression of VEGF (white) and Wnt3a (black). Although there was no difference between VEGF levels, there was a significant difference in the amount of Wnt3a between the two groups (error bars indicate ±SEM; *, p < .05). Abbreviations: MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WT, wild-type.

dbMSCs Have Impaired Homing Capacity During Injury

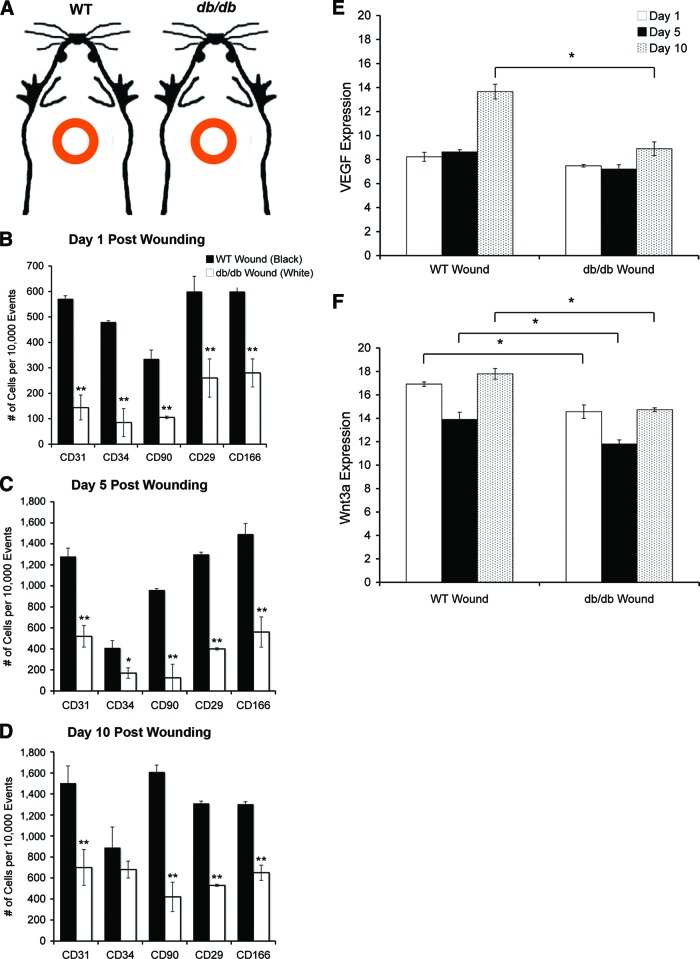

Endogenous MSCs contribute to healthy cutaneous wound healing through mobilization and targeting to the site of injury [22–24]. We implemented a full-thickness excisional splint wound to permit assessment of both host mobilization of endogenous MSCs and regenerative capacity of exogenous MSCs. We first evaluated the host response to injury by creating a dorsal wound in the backs of db/db and WT animals without cellular engraftment (PBS-only; Fig. 4A). Circulating MSCs in the peripheral blood are difficult to quantify [25], so we biopsied and dissociated the entire wound beds to detect endogenous MSCs and to evaluate specific targeting. After 1, 5, and 10 days, we evaluated the number of endogenous stem cell populations that homed to the site of injury (Fig. 4B–4D). At all time points, we found that there were significantly fewer (Fig. 4B–4D, **, p < .001) positively labeled endogenous MSCs (CD29, CD90, CD166) recruited to the db/db wound compared with the WT wound. Cells positively labeled with CD29, CD44, CD90, and CD166 were negative for CD14, CD34, and CD45. At days 1 and 5, there were also significantly fewer (p < .05) endothelial progenitor cells (CD31, CD34) in the db/db wound (Fig. 4B–4D).

Figure 4.

Quantification of endogenous stem cell populations after wounding. (A): An excisional wound model using a donut-shaped splint kept the wounds open, and phosphate-buffered saline (vehicle-only) or cells were delivered to db/db or WT mice. We recorded the baseline levels of healing with no therapeutic interference. (B–D): Population analysis of diabetic and WT MSCs from dissociated wound beds from db/db and WT mice with no grafted MSCs using flow cytometric analysis using the MSC markers CD29 and CD90 and the endothelial progenitor marker CD34, at 1 (B), 5 (C), and 10 (D) days postwounding (n = 5 per time point; *, p < .05; **, p < .001). (E, F): Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis was performed on naïve wound bed biopsies, and the levels of VEGF (E) and Wnt3a (F) were quantified at days 1, 5, and 10 from WT and db/db wound beds. There was a significant decrease in the level of Wnt3a expression in the db/db wound at days 1, 5, and 10, and by day 10 there was a significant decrease in the level of VEGF expression in the db/db wound (*, p < .05). Abbreviations: VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WT, wild-type.

Biopsied db/db and WT MSCs were then fixed and labeled with SDF-1, a chemokine required for homing of progenitor cells to ischemic and injured tissues [26]. There was a marked reduction in the level of expression of SDF-1 in the dbMSCs in vitro at passage 4 compared with the WT (Fig. 5A–5G). Decreases in other homing factors, such as matrix metalloproteinase-2, were also noted in the PCR array (supplemental information Table 1).

Figure 5.

SDF-1 expression in WT and diabetic (db) MSCs in vitro. WT (A–C) and dbMSCs (D–F) at passage 4 were also stained for positive MSC marker CD44 (Cy2, green) and SDF-1 (Cy3, red). A greater percentage of wtMSCs were SDF-1 positive compared with the dbMSCs in culture. Abbreviations: SDF-1, stromal-derived factor-1; WT, wild-type.

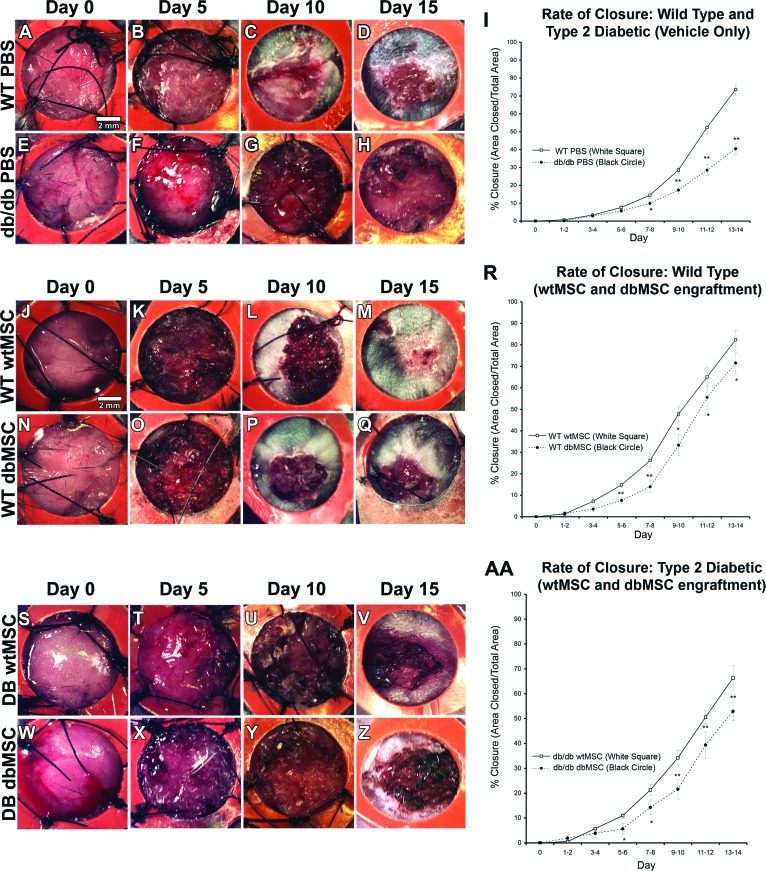

dbMSCs Have Impaired Therapeutic Capacity Compared with Their Wild-Type Counterparts

Without any therapeutic intervention, naïve wounds (PBS-only) in the db/db mouse exhibited a significant delay in wound closure compared with a nondiabetic mouse (Fig. 6A–6H). At day 14, only 40% ± 3.1% (p < .05) of the control db/db wound area was closed compared with the 73% ± 3.2% closure area seen in control WT wounds (Fig. 6I). We then evaluated the therapeutic capacity of MSCs from diabetic and nondiabetic subjects by grafting dbMSCs and wtMSCs in the excisional splint wound (Fig. 6J–6Q, 6S–6Z). We found that wtMSC engraftment accelerated wound closure both in db/db and WT mice. The closure area in both hosts was significantly increased (p < .05) by day 5, and this acceleration was sustained at all subsequent time points (Table 1; Fig. 6R, 6AA). The rate of closure in the wtMSC grafted db/db mouse reached 66% ± 5% at day 14, nearly reaching the rate of physiologic closure seen in the naïve WT animal, despite the diabetic physiology of graft recipients (Fig. 6R). Closure area was also accelerated in the wtMSC-engrafted WT animals to 82% ± 4.4% at the same time point (Fig. 6R, n = 20 each for control db/db and WT, and n = 10 each for wtMSC-engrafted db/db and WT).

Figure 6.

Wound healing was impaired in diabetic animals, and dbMSCs had reduced therapeutic capacity. The progress of wound closure of dorsal, full-thickness excisional wounds held open by sutured (black threads) silicone splints (orange) following delivery of vehicle (PBS) to DB or nondiabetic (WT) subjects was recorded. Control WT mice (A–D) and db/db mice (E–H) received PBS (vehicle only). (I): db/db mice receiving only PBS exhibited significantly delayed wound closure compared with WT mice. WT (J–M) and db/db (S–V) mice received 1 × 106 wtMSCs derived from WT mice or WT (N–Q) and db/db (W–Z) mice received 1 × 106 dbMSCs derived from db/db mice. (R): In the WT host, dbMSC engraftment did not improve WT closure compared with PBS, but wtMSC engraftment indicated improved closure in the WT mouse. (AA): In the db/db host, wtMSCs improved closure in db/db mouse, but dbMSC engraftment alone improved closure in db/db mice but not in WT mice. The extent of reepithelialization and granular tissue formation was monitored daily; representative images are shown at initial treatment (day 0) and at 5, 10, and 15 days postengraftment (n = 10–13 per condition). Each data point represents the mean of the percentage of the area closed (I, R, AA). Closure was calculated from stereological analysis of micrographs using the Cavalieri point probe estimator (error bars indicate ±SEM; n = 10–13 per group; *, p < .05; **, p < .001). Abbreviations: DB, diabetic; dbMSC, diabetic mesenchymal stem cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild-type; wtMSC, wild-type mesenchymal stem cell.

In culture, we were able to select for a subpopulation of proliferating dbMSCs, which increased the number of viable cells and reduced the time between passages. We evaluated these higher performing dbMSCs for their regenerative capacity in diabetic subjects; these allogeneic grafts represented the potential performance of autologous engraftment therapies in human diabetic patients. The db/db wounds receiving dbMSCs significantly improved healing (p < .05) by day 7, which was sustained until day 14 (Table 1). By day 14, db/db wounds engrafted with dbMSCs reached 53% ± 4% closure (Fig. 6AA). However, although dbMSCs significantly improved closure (p < .05) in db/db animals (with the exception of days 9–10; Table 1), they did not produce any difference in wound closure relative to naïve wounds (PBS-only) when delivered to the WT animals. WT animals receiving dbMSCs experienced no significant improvement and the normal metabolic environment did not rescue the capacity of the dbMSCs (Table 1). After day 5, dbMSCs produced significantly less closure than the wtMSCs independently of whether the subject was a diabetic or nondiabetic animal (Table 1; Fig. 6R, 6AA; n = 20 each for control db/db and WT, and n = 10 each for dbMSC-engrafted db/db and WT). Despite engraftment of this selected high-performing population, dbMSCs could not stimulate wound closure to the level produced by grafted wtMSCs. Furthermore, placement of dbMSCs in a normal metabolic environment (nonhyperglycemic and nonobese) did not restore this regenerative capacity and could not improve closure in a healthy animal.

MSC Engraftment Did Not Improve Metabolic Outcomes, Such as Hyperglycemia and Obesity, in db/db Mice

Systemic MSC engraftment has been reported to assist in β-cell regeneration and consequential improvements in hyperglycemia [27]. To determine the effects of local MSC engraftment to the whole animal, weight and plasma glucose levels were recorded. At day 0, under all treatment conditions, db/db animals had a glucose level of 307 ± 16 mg/dl. The mean weight of these 8-week-old animals was 40 ± 2 g. Irrespective of treatment, all WT animals were able to achieve full closure by day 16. Untreated db/db mice took more than 30 days to heal, the wtMSC treatment group took 18 ± 2 days, and dbMSC-treated animals took 21 ± 3 days. At the time of closure, db/db mice engrafted with wtMSCs had a plasma glucose level of 403 ± 11 mg/dl, animals engrafted with dbMSCs were at 443 ± 33 mg/dl, and PBS-only animals were at 421 ± 15 mg/dl. The average weight for all db/db animals was 47 ± 4 g. We found no significant correlation between the direct engraftment of db or wtMSCs, wound healing, and these metabolic parameters in our study. Consistent with previous studies, the rate of wound healing was not correlated to the levels of hyperglycemia in the animal [28].

Discussion

There is considerable interest in developing therapeutic use of autologous stem cells for a wide range of diseases. Whereas endogenous tissue stem cell populations, including bone marrow-derived cells, may provide additional regenerative capacity and are good candidates for cell-mediated therapies, they have not been evaluated within a disease state such as type 2 diabetes. We report here that prolonged disease states may impair the regenerative capacity of such endogenous tissue stem cells. In mice experiencing severe complications of type 2 diabetes, we found that bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells were fewer in number than healthy controls, showed altered proliferation, showed reduced viability, had an altered transcriptional profile, and were severely impaired in their regenerative capacity relative to MSCs from healthy mice. Importantly, our data suggest that the pathophysiology associated with type 2 diabetes produces cell-autonomous impairment, as these MSCs remained impaired when placed in healthy environments.

Type 2 diabetes is associated with complications in multiple organ systems throughout the body and underlies severe vascular damage, which can increase tissue damage and limit repair capacity [29, 30]. Long ago, Cohnheim hypothesized that cells arising from the bloodstream are responsible for all tissue repair in mammals [31]. Although there is now an appreciation that many tissues contain endogenous stem/progenitor cells, this hypothesis has been affirmed by evidence that precursor cells from the bone marrow replenish the reparative stem-like cells in tissues throughout the body [3, 32]. Wounding in diabetic patients stimulates an increase in the number of circulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+) and peripheral EPCs (CD34+) from the bone marrow to the periphery and lymphoid tissue compared with matched nonwounded controls [11]. This mobilization of cells is required for healing, but type 2 diabetic patients have significantly fewer EPCs, resulting in severe vascular dysfunction and impaired healing [6, 9]. Endogenous MSCs also respond to environmental cues and play a major role in tissue repair throughout the body [3]. For example, MSCs provide the supportive microenvironment necessary for hematopoiesis and maintain the sinusoidal network [33]. MSCs express HSC maintenance genes (Angpt1+, Vcam1+, Cxcl12+, c-Kit1+) responsible for HSC progenitor cells homing, and the depletion of MSCs results in a major reduction of the number of HSCs within the bone marrow [34].

In normal wound healing, bone marrow cells and stem cells in the local skin and blood vessels are recruited to the area of injury [24, 35]. These stem cells or pericytes from the vasculature are believed to be mesenchymal stem cells and contribute to wound healing [3, 35]. Type 2 diabetes produces cellular impairment in many organ systems, which may result from nongenetic factors related to the disease, such as obesity, elevated corticosterone, increased inflammation, and insulin resistance. Glucocorticoid dysfunction and hyperglycemia have been associated with the increased proliferation and decreased survival of neural progenitors underlying impaired neurogenesis in type 2 diabetic rodent models [36, 37]. We also observed increased proliferation and decreased survival of dbMSCs and saw that the environmental glucose levels did not change the functional capacity of MSCs. These data are consistent with previous studies indicating that impaired EPC mobilization and wound healing in diabetic rodents could not be rescued with insulin and reduced hyperglycemia [28, 38]. We also noticed a deficiency in the level of SDF-1 expression indicating impairment of homing capacity in these cells to areas of injury. Early exposure to hyperglycemia has been shown to predispose an individual to complications and create epigenetic modifications leading to a phenomenon called metabolic memory [39, 40]. Based on these results, we believe that MSCs share a vulnerability to the pathophysiology and retain a metabolic memory of type 2 diabetes similar to other differentiated cells, such as nerves, blood vessels, and pancreatic β-cells in the body [40, 41].

To address this deficiency in dbMSCs, we also evaluated the level of gene expression using RT-PCR. This is the first study to evaluate the levels of endogenous expression of VEGF and Wnt3a in the wild-type and diabetic animal. We evaluated these two factors both in the endogenous MSC population after enrichment and in the response to wounding. Proangiogenic factor VEGF promotes healing through neovascularization and promotes MSC proliferation, whereas the proliferative factor Wnt3a, an autocrine signal expressed by MSCs, promotes differentiation, migration, proliferation, and invasion in the areas of injury [20, 42]. When VEGF was examined after selection in culture, dbMSCs showed similar levels of VEGF expression compared with the wild-type cells, and there was a difference in the level of VEGF expression only 10 days after wounding. However, there was a considerable reduction in the levels of Wnt3a. Even after selection, the dbMSCs did not have the same levels of expression, and there was significant impairment at days 1, 5, and 10 in the diabetic wound. The impairment in Wnt3a expression could be one underlying cause of the diminished therapeutic capacity of dbMSCs. The performance of dbMSCs could not be restored to WT levels under standard culture conditions or in a healthy animal with normal glucose regulation. In contrast, wtMSCs experienced no decline in function in the hyperglycemic db/db host, suggesting irreversible damage in the functional capacity of dbMSCs as a result of the diabetic background. These data suggest that functional impairments of MSCs are acquired and become cell autonomous in animals experiencing severe type 2 diabetes and possibly other chronic disease pathophysiologies.

Conclusion

We propose that MSC impairment is a complication of diabetes. This impairment in MSC proliferation, viability, and number in diabetic patients may underlie defective tissue maintenance, delayed wound healing, and immune system complications. Whether stem cell impairment limits only the regenerative capacity of endogenous stem cells in type 2 diabetes or contributes to its complications as a result of reduced contribution to tissue maintenance, these data indicate that the utility of autologous stem cell replacement therapy in type 2 diabetes and possibly other chronic diseases may be limited in the absence of some adjunctive therapy for the stem cells themselves. These data further suggest that MSC populations may be a suitable therapeutic target to improve symptoms and complications associated with chronic disease. For example, strategies promoting proliferation in vivo could activate endogenous stem cells in diabetic tissue [43], potentially advancing autologous therapies and ameliorating the devastating complications associated with this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Department of Energy Grant DE SC001810 (to D.A.P.) and American Diabetes Association Clinician Scientist Training Grant 7-08 CST-02 (to L.S.).

Author Contributions

L.S.: concept and design, data collection and analysis, interpretation, financial support, manuscript writing; D.A.P.: financial support, concept and design, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bild DE, Selby JV, Sinnock P, et al. Lower-extremity amputation in people with diabetes: Epidemiology and prevention. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:24–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trousdale RK, Jacobs S, Simhaee DA, et al. Wound closure and metabolic parameter variability in a db/db mouse model for diabetic ulcers. J Surg Res. 2009;151:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stappenbeck TS, Miyoshi H. The role of stromal stem cells in tissue regeneration and wound repair. Science. 2009;324:1666–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1172687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuroda Y, Kitada M, Wakao S, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal cells: How do they contribute to tissue repair and are they really stem cells? Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2011;59:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prockop DJ, Kota DJ, Bazhanov N, et al. Evolving paradigms for repair of tissues by adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs) J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2190–2199. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volarevic V, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML, et al. Concise review: Mesenchymal stem cell treatment of the complications of diabetes mellitus. Stem Cells. 2011;29:5–10. doi: 10.1002/stem.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, et al. Concise review: Mesenchymal stem cells: Their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolar J, Le Blanc K, Keating A, et al. Concise review: Hitting the right spot with mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1446–1455. doi: 10.1002/stem.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao YF, Chen LL, Zeng TS, et al. Number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells as a marker of vascular endothelial function for type 2 diabetes. Vasc Med. 2010;15:279–285. doi: 10.1177/1358863X10367537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung C, Rafnsson A, Shemyakin A, et al. Different subpopulations of endothelial progenitor cells and circulating apoptotic progenitor cells in patients with vascular disease and diabetes. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiorina P, Pietramaggiori G, Scherer SS, et al. The mobilization and effect of endogenous bone marrow progenitor cells in diabetic wound healing. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1369–1381. doi: 10.3727/096368910X514288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldorf AR, Ruderman N, Diamond RD. Specific susceptibility to mucormycosis in murine diabetes and bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:150–160. doi: 10.1172/JCI111395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoji T, Koyama H, Morioka T, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is involved in impaired angiogenic response in diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:2245–2255. doi: 10.2337/db05-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terashi H, Izumi K, Deveci M, et al. High glucose inhibits human epidermal keratinocyte proliferation for cellular studies on diabetes mellitus. Int Wound J. 2005;2:298–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4801.2005.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerman OZ, Galiano RD, Armour M, et al. Cellular dysfunction in the diabetic fibroblast: Impairment in migration, vascular endothelial growth factor production, and response to hypoxia. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63821-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson MA, Thompson JS. Wound splinting modulates granulation tissue proliferation. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galiano RD, Tepper OM, Pelo CR, et al. Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1935–1947. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63754-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin H, Xu R, Zhang Z, et al. Implications of the immunoregulatory functions of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of human liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:19–22. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shang YC, Wang SH, Xiong F, et al. Wnt3a signaling promotes proliferation, myogenic differentiation, and migration of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1761–1774. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaels J, 5th, Churgin SS, Blechman KM, et al. db/db mice exhibit severe wound-healing impairments compared with other murine diabetic strains in a silicone-splinted excisional wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:665–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fathke C, Wilson L, Hutter J, et al. Contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to skin: Collagen deposition and wound repair. Stem Cells. 2004;22:812–822. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chino T, Tamai K, Yamazaki T, et al. Bone marrow cell transfer into fetal circulation can ameliorate genetic skin diseases by providing fibroblasts to the skin and inducing immune tolerance. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:803–814. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verstappen J, Katsaros C, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, et al. The recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells to skin wounds is independent of wound size. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: The devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Z, Ou L, Zhou X, et al. Targeted migration of mesenchymal stem cells modified with CXCR4 gene to infarcted myocardium improves cardiac performance. Mol Ther. 2008;16:571–579. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urban VS, Kiss J, Kovács J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells cooperate with bone marrow cells in therapy of diabetes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:244–253. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pietramaggiori G, Scherer SS, Alperovich M, et al. Improved cutaneous healing in diabetic mice exposed to healthy peripheral circulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2265–2274. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiber GE, Lipsky BA, Gibbons GW. The burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Am J Surg. 1998;176(2A suppl):5S–10S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohnheim J. Ueber entzündung und eiterung. Path Anat Physiol Klin Med. 1867:40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prockop DJ, Gregory CA, Spees JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: Harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(suppl 1):11917–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834138100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bianco P, Robey PG, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: Revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang BT, Yan Y, Dempsey RJ, et al. Impaired neurogenesis in adult type-2 diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2009;1258:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stranahan AM, Arumugam TV, Cutler RG, et al. Diabetes impairs hippocampal function through glucocorticoid-mediated effects on new and mature neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:309–317. doi: 10.1038/nn2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher KA, Liu ZJ, Xiao M, et al. Diabetic impairments in NO-mediated endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and homing are reversed by hyperoxia and SDF-1α. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1249–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI29710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalmers J, Cooper ME. UKPDS and the legacy effect. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1618–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0807625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirola L, Balcerczyk A, Okabe J, et al. Epigenetic phenomena linked to diabetic complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:665–675. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–312. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong X, Zheng F, Guo LY, et al. [VEGF promotes the proliferation of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells through ERK1/2 signal pathway] Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2010;18:1292–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daley GQ, Scadden DT. Prospects for stem cell-based therapy. Cell. 2008;132:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]