Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) caused by mutation of rhodopsin (RHO) was investigated in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from an RP patient. In differentiated rod cells, distribution of RHO protein and expressions of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress markers strongly indicated the involvement of ER stress, and significantly decreased rod cell numbers suggested an in vitro model of rod degeneration. These findings show that integration-free iPSCs can be generated and patient-specific iPSCs differentiated into retinal cells, indicating a potential role for patient iPSCs as an ER stress model.

Keywords: Retina, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Retinal photoreceptors, Differentiation

Abstract

We investigated retinitis pigmentosa (RP) caused by a mutation in the gene rhodopsin (RHO) with a patient-specific rod cell model generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from an RP patient. To generate the iPSCs and to avoid the unpredictable side effects associated with retrovirus integration at random loci in the host genome, a nonintegrating Sendai-virus vector was installed with four key reprogramming gene factors (POU5F1, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC) in skin cells from an RP patient. Subsequent selection of the iPSC lines was on the basis of karyotype analysis as well as in vitro and in vivo pluripotency tests. Using a serum-free, chemically defined, and stepwise differentiation method, the expressions of specific markers were sequentially induced in a neural retinal progenitor, a retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) progenitor, a photoreceptor precursor, RPE cells, and photoreceptor cells. In the differentiated rod cells, diffused distribution of RHO protein in cytoplasm and expressions of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress markers strongly indicated the involvement of ER stress. Furthermore, the rod cell numbers decreased significantly after successive culture, suggesting an in vitro model of rod degeneration. Thus, from integration-free patient-specific iPSCs, RP patient-specific rod cells were generated in vitro that recapitulated the disease feature and revealed evidence of ER stress in this patient, demonstrating its utility for disease modeling in vitro.

Introduction

The retina is essential for vision. The many distinct layers of this tissue include the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the neural retina with its photoreceptor cells. Photoreceptor cells convert light into neural signals, which are then transmitted to the next order of neurons. The death of photoreceptor cells in retinal degenerative diseases is the leading cause of inevitable and irreversible blindness worldwide. Rescuing the degenerated retina is still a major challenge.

Cell replacement is now one of the most promising therapies for human degenerative diseases [1–3]. Pluripotent stem cells, able to differentiate into a number of cell types, are the best source of cells for cell replacement, since mature cells are not able to sufficiently provide the number necessary [4]. Methods to induce stem cells to a pluripotent condition or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology have become extremely important for regenerative medicine, because the ethical issues pertaining to the use of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are no longer relevant [5, 6]. In addition, patient-specific iPSCs are useful for the study of disease mechanisms and personalized drug therapy [7].

For the study of retinal degenerative diseases using cell replacement, the appropriate induction of premature retinal cells from pluripotent stem cells is essential. Basing her research on the observation that, in the embryo, different types of retinal neurons are produced in a spatial-temporal pattern, Ikeda and colleagues [8, 9] designed a method involving a serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates (serum-free embryoid body [SFEB]) to generate retinal progenitor cells (pax6+/rx+ or pax6+/mitf+) from ESCs. With the SFEB method, Osakada et al. [9] successfully generated RPE and mature photoreceptor cells from mouse, monkey, and human ESCs.

Most recently, we successfully differentiated iPSCs into retinal cells using the same method [10] and with a modified approach replacing recombined proteins with small molecules [11]. Basing our research on sequential pluripotent induction of human stem cells and in vitro differentiation of retinal cells, we and another group proved that patient-specific iPSCs could be used in retinal disease modeling and drug evaluation [12, 13]. In the above-mentioned studies, retroviruses were broadly used to introduce four key reprogramming pluripotency factors to generate iPSCs. However, this approach had an unfortunate flaw in that the DNA of viral transgenes may randomly integrate into the host cell genome, leading to the risk of unpredictable and adverse effects on function. Even with careful selection of iPSCs with a low copy number of integrations, the potential risk of genomic interruption remains.

In the present study, integration-free iPSCs were generated from a patient with a known G188R mutation in the rhodopsin (RHO) gene. The disease features of the differentiated patient-specific rod cells (Fig. 1A) were then investigated. This study confirms that, via integration-free iPSCs, patient-specific rod cells may recapitulate retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in vitro and thus are an appropriate cell model to study human retinal degenerative diseases.

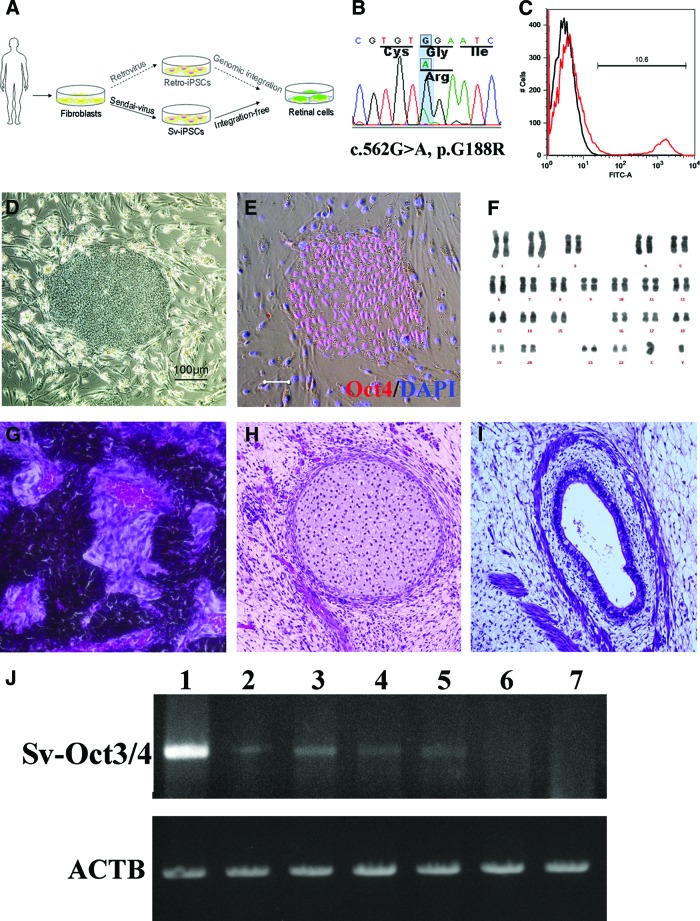

Figure 1.

Generation of patient-specific iPSCs. (A): Schematic diagram of this study. Compared with patient-iPSCs generated by the retroviral method, nonintegrative Sendai virus (SeV)-iPSCs from the same retinitis pigmentosa patient with a rhodopsin (RHO) mutation are more appropriate for disease modeling. (B): Sequence chromatogram of the RHO gene G188R mutation identified in patient-derived fibroblasts. (C): Representative result of SeV infection efficiency. The SeV infection efficiency was tested using SeV18+ green fluorescent protein (GFP)/TSΔF. Six days after infection of fibroblast cells, 10.6% of cells were positive for GFP (red histogram). Black histogram indicates a negative control. (D): The colony morphology of the patient-specific iPSCs. (E): Specific expression of the pluripotency marker Oct3/4 in the patient-derived iPSCs. Scale bar = 20 μm. (F): The results of karyotype analysis. (G–I): Histology of three germ layer derivatives in a teratoma formed by patient-derived iPSCs. (J): Ectopic expression of the Sendai viral Oct3/4 gene in the early passage iPSCs. Lane 1, positive control; lanes 2 and 3, 2nd passage iPSC lines of Sev3 and Sev9; lanes 4 and 5, 3rd passage Sev3- and Sev9-iPSC lines; lane 6, 10th passage Sev9-iPSC; lane 7, differentiated (day 40) Sev9-iPSCs. Abbreviations: ACTB, housekeeping β-actin gene; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; Sv, Sendai virus; Sv-Oct3/4, Sendai viral Oct3/4 gene.

Materials and Methods

Fibroblast Culture

Skin tissues were obtained by biopsy from an adult patient with RP and then transferred on ice directly to the laboratory. To establish primary fibroblasts, the tissues were minced and cultured in an MF-start primary culture medium (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan, http://www.toyobo.co.jp/e) on gelatin-coated dishes. After 3–5 days of culture, fibroblasts grew from the skin fragments. The skin tissue was removed, and MF medium (Toyobo) was used to expand the cells. DNA was extracted from the fibroblasts to confirm the genotype.

Infection Efficiency of Sendai Virus

The Sendai virus (SeV) infection efficiency was tested by SeV18+ green fluorescent protein (GFP)/TSΔF, an SeV vector containing SeV18 with the GFP gene and a functional mutation for temperature sensitivity in the viral F-gene (TSΔF; kindly provided by DNAVEC, Tsukuba, Japan, http://www.dnavec.co.jp). Six days after infection of fibroblast cells, the percentage of cells testing positive for GFP was analyzed by flow cytometry, following the manufacturer's protocol (FACScanto II; BD Biosciences, San Diego, http://www.bdbiosciences.com).

Human iPSC Generation

The four F-deficient Sendai-virus (SeV/ΔF) vectors (SeV18+ Homo sapiens [HS]-POU5F1/TSΔF, SeV18+HS-SOX2/TSΔF, SeV18+HS-KLF4/TSΔF, and SeV(HNL)c-MYCQC/TS15ΔF) were kindly provided by the DNAVEC Corporation [14]. All fibroblasts were infected with all four of these SeV/ΔF vectors containing the reprogramming gene factors Pou5f1 (Oct3/4), Sox2, Klf4, or c-Myc, respectively, twice within 48 hours. The cells were then trypsinized and transferred onto murine embryonic fibroblast layers (1 × 105 cells per 100-mm dish). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com) supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR; Invitrogen), and 4 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA, http://www.upstate.com). Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) colonies were picked up manually and maintained on a feeder layer of mitomycin C-treated SNL cells (the murine-derived fibroblast cell line STO transformed with neomycin resistance and murine leukemia inhibitory factor genes) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was performed to verify the expression of the reprogramming factors harbored by the SeV in either the iPSCs or differentiated samples, as described previously [14].

In Vitro and In Vivo Pluripotency Tests

To test the pluripotency of the established iPSC lines, immunocytochemical staining was performed. Cultured iPSCs were trypsinized to remove the feeder cells. Suspended iPSCs (a total of 1 × 107 cells) were then injected subcapsularly into the testes of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice, a strain of mice lacking both T and B lymphocytes. The testes were fixed and sectioned for hematoxylin-eosin staining after 4 weeks.

Karyotype Analysis

Stably passaged iPSCs (Sev9) were harvested for karyotype testing to examine chromosomal integrity using a standard G-band technique (300–400 band level).

Differentiating Retinal Cells from iPSCs

The Sev9-iPSCs were differentiated in vitro as described previously [9, 15]. iPSCs derived from a normal individual and the RP patient via the retroviral method were also included. In brief, iPS colonies were dissociated into clumps after removing feeder cells. iPS clumps were moved to a nonadhesive 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine-treated dish (Nunc, Rochester, NY, http://www.nuncbrand.com) in maintenance medium for 3 days and then in differentiation medium for 12 days with Lefty-A (or SB-431542) and Dkk-1 (CKI-7) treatment [11]. On day 21, the cells were plated en bloc on poly-d-lysine/laminin/fibronectin-coated eight-well culture slides (BD Biocoat; BD Biosciences) at a density of 15–20 aggregates per cm2. The cells were cultured in 10% KSR-containing differentiation medium until day 60. Cells were further treated with 100 nM retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) and 100 μM taurin (Sigma-Aldrich) in photoreceptor differentiation medium.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 4°C and then permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 45 minutes. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to an overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C after blocking for 1 hour in 5% goat serum. Washed cells were then treated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were sandwiched between the slides and coverslips and viewed under a confocal microscope.

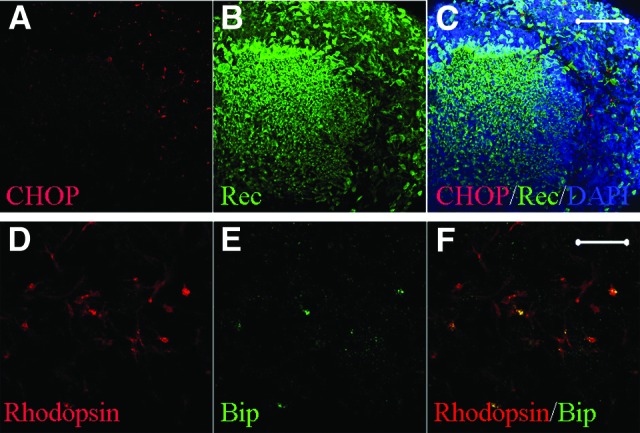

Cell Counting and Analysis

As described previously, rod cells derived from normal ESCs or iPSCs and positive for rhodopsin (RET-P1 clone) always appeared at approximately differentiation day 120, and the cell number increased slightly by day 150. In this study, we counted the rod cells at these two time points. Analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni analysis was used to determine statistical significance (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, http://www.graphpad.com). A probability value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Genotyping of the Patient-Derived Fibroblasts

Mutation in an autosomal dominant RP patient has been identified previously with denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography sequencing [16]. To confirm the mutation in the patient-specific fibroblast cells, RHO gene exon 3 was amplified and read by direct sequencing. As shown in Figure 1B, the c.562G>A mutation was identified, indicating that the fibroblasts were derived from the same patient.

Generation of SeV-iPSCs

The fibroblasts transduced with the SeV18+GFP/TSΔF vector were positive for GFP expression, indicating that exogenous GFP had been successfully introduced (Fig. 1C). On the basis of the in vitro reprogramming strategy with SeV, ESC-like colonies appeared 3 weeks later. The colonies were isolated as candidate iPSC lines for passaging (Fig. 1D). Selected SeV-iPSC lines expressed typical pluripotency markers, including Oct3/4 (Pou5f1), Nanog, SSEA3, and SSEA4 (Fig. 1E; data not shown). Ectopic expression of the reprogramming factors was confirmed in the early passage cells. However, the expression levels decreased in both cells that had been passaged 10 times and in differentiated cells, indicating a dilution effect due to successive cultures (Fig. 1J).

For in vivo testing, the cells were injected into SCID mice. Ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm-derived tissues were confirmed in the induced teratoma (Fig. 1G–1I). Karyotype analysis demonstrated the chromosomal integrity of the SeV-iPSCs (Sev9 line; Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results provided evidence that the nonintegrative SeV-iPSCs possessed the same pluripotency and chromosomal identity as traditional iPSCs generated by retrovirus.

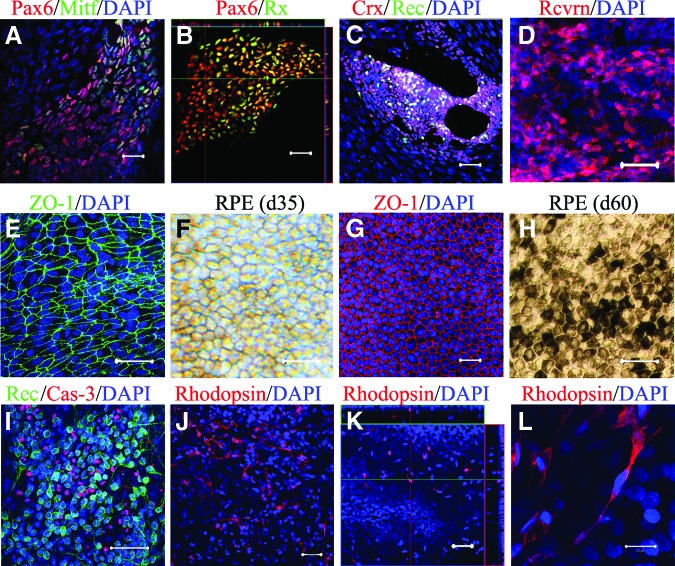

Induction of Retinal Progenitor Cells

For retinal induction, we adopted the SFEB method, as described previously [9, 11, 15]. Using a floating culture in a low-adherent dish, an embryoid-like body was formed by day 20. After transfer to an adherent culture, a few pigmented RPE-like cell blocks (∼2%) appeared as early as day 30. Neuroretinal progenitor cells (Pax6+/Rx+) and RPE progenitors (Pax6+/Mitf+) were revealed in ∼8% and ∼5% of the colonies, respectively. By day 40, the percentage of Pax6+/Rx+ and Pax6+/Mitf+ colonies increased significantly (Fig. 2A, 2B). Differentiated cells, positive for recoverin (a common marker for cone, rod, and cone bipolar cells) and Crx (cone-rod homeobox-containing gene; a specific marker for both cone and rod cells), appeared by day 60 (Fig. 2C, 2D), suggesting the successful induction of the postmitotic photoreceptor precursor. These data demonstrated the successful induction of retinal progenitor cells from SeV-iPSCs of the RP patient.

Figure 2.

Directed retinal differentiation of the patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. On day 40, induced Pax6+Mitf+ RPE progenitor cells (A) and Pax6+Rx+ neuroretinal progenitor cells (B) were observed. (C): On day 60, cells positive for Crx and recoverin appeared. (D): Recoverin+ cells significantly increased by day 90; immature RPE (RPE-like) cells displayed a net-like shape (E) and did not express pigments on day 35 (F). Typical RPE cells displayed hexagonal shape (G) and pigmentation (H) on day 60. (I): Apoptotic cells (caspase-3+) were found in the recoverin+ cell cluster. (J): Induced rod (rhodopsin+) cells on day 120. (K): Induced rod cells were usually observed on the top of ground cells on day 120. (L): Rhodopsin+ cells displayed neural processes and stick-like shape. Scale bars = 20 μm. Abbreviations: Crx, cone-rod homeobox-containing gene; d, day; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Rec or Rcvrn, recoverin; RPE, retinal pigment epithelial.

Induced Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells

As described above, RPE-like cells appeared as early as day 30 and displayed a fishnet-like morphology (Fig. 2E, 2F). By day 60, the cells had notably expanded, with typical features (Fig. 2G, 2H). We isolated the RPE cell blocks and replated them onto a laminin-coated dish. The RPE cells proliferated and grew into a monolayer. Besides the characteristic hexagonal shape, pigmentation, domes, and tight-junctions were usually found in the sheet of cells (data not shown), which suggested a water-pump function in the RPE cells.

Patient-Specific Rod Cells Recapitulate Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in RP

As reported previously, rod cells can be induced by a stepwise protocol [9, 10]. We adopted the same protocol and examined the differentiation of rod cells using SeV-iPSCs (Sev9) derived from the RP patient. By differentiation day 60, immunocytochemistry revealed that 6% of the colonies were positive for the photoreceptor markers Crx and recoverin. This percentage was significantly increased through further induction by day 90. Interestingly, apoptotic cells were observed in the cluster of recoverin+ colonies (Fig. 2I), suggesting an early-stage disease manifestation or developmental apoptosis.

After differentiation day 110, the cells expressed RHO protein, which was detected by immunostaining. As a transmembrane protein, RHO is typically distributed on the cell membranes [12]. However, SeV-iPSC-derived rod cells of this patient showed a cytoplasmic distribution of RHO staining (Fig. 2J, 2L).

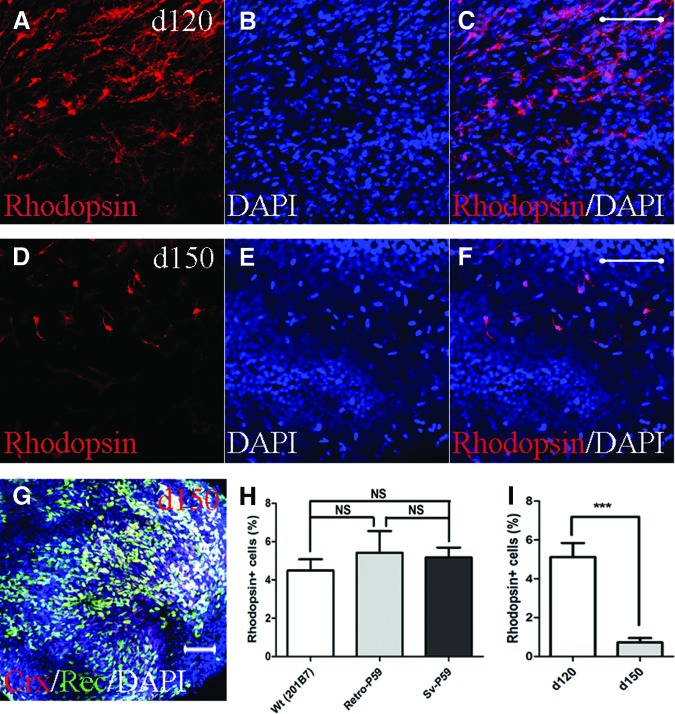

Importantly, the patient-derived rod cells coexpressed binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) (also known as DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3), both of which are conventional markers of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Fig. 3). No significant differences in the number of rod cells were observed among the SeV-iPSCs, retrovirus-derived iPSC clones (retro-iPSCs), and normal iPSCs at day 120 (Fig. 4). Through a long-term culture, the rod cell numbers decreased significantly by day 150. Immunocytochemically, few rod-specific rhodopsin+ cells were observed, whereas cells positive for recoverin and Crx were frequently seen (Fig. 4G).

Figure 3.

Patient-specific retinal cells showed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. ER stress in the patient-specific retinal cells. (A–C): CHOP+ cells in recoverin+ cell cluster (day 120). (D–F): Rhodopsin+ cells coexpressed Bip, a conventional marker for ER stress. Scale bars = 20 μm. Abbreviations: Bip, binding immunoglobulin protein (a molecular chaperone of binding immunoglobulin protein/Grp78 involved in ER stress); CHOP, a proapoptotic protein responsive to ER stress; Rec, recoverin.

Figure 4.

Patient-derived rod cells underwent degeneration in vitro. Representative figure of induced rod cells (RHO+) on day 120 (A–C) and day 150 (D–F). (G): Cells positive for Crx and recoverin remained on day 150. (H): No significant differences in differentiated RHO+ cell number among cells derived from a wild-type induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line (201B7) and patient-specific iPSCs obtained through the retroviral (retro-P59) and Sendai viral (Sev-P59) methods. (I): Changes in the number of cells indicated significant rod degeneration under in vitro culture conditions by day 150. Scale bars = 20 μm. ***, p < .001. Abbreviations: Crx, cone-rod homeobox-containing gene; d, day; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; NS, no statistical significance; Rec, recoverin; Sv, Sendai virus; Wt, wild-type.

Taken together, these results demonstrated that patient-derived SeV-iPSCs can be differentiated into rod cells and, in the present study, recapitulated the rod-specific pathogenesis of the RP patient. Importantly, patient-specific rod cells displayed characteristics associated with ER stress, supporting the hypothesis that rod degeneration caused by the RHO mutation involves the ER stress pathway.

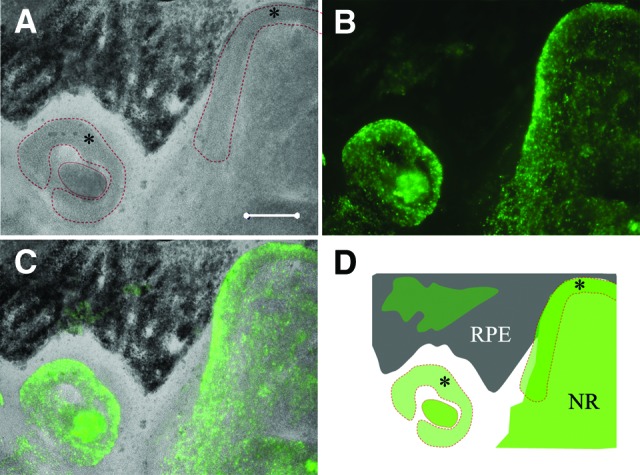

Distribution of Induced Retinal Cells in the Culture Dish

Following the formation of the embryoid body in the SFEB floating culture nonadherent dish, the cell aggregates were replated onto a fibronectin/laminin/poly-d-lysine-coated dish suitable for cell adhesion and neural differentiation. By differentiation day 60, RPE cells were usually observed near the photoreceptor cell clusters. Interestingly, it was found that either of these cells might surround the other in the dish (Fig. 5). Optic cup-like structures were usually seen that were positive for recoverin (Fig. 5). These results indicated that retinal neurons during SFEB culture differentiation always adjoined the RPE cells, which were usually identifiable without immunostaining and sometimes displayed optic cup-like morphology.

Figure 5.

Localization of differentiated neuroretinal cells. (A): RPE cells (black area) and optic cup-like organizations (*) on day 60 (phase). (B): Recoverin+ cell clusters. (C): Overlapped. (D): Schema of RPE and neuroretina differentiation in vitro. Scale bars = 200 μm. Abbreviations: NR, neural retina; RPE, retinal pigment epithelial.

Discussion

RP comprises a group of retinal diseases caused by mutations in a cluster of genes. Mutation in the RHO gene is one of the leading causes of RP [17]. Because of the unavailability of patient-specific retinal tissue, specifically rod cells, the underlying mechanism(s) of the disease remain largely unknown. The development of iPSC technology enables us to generate patient-specific retinal cells or tissues to study human diseases. We previously generated patient-specific iPSCs using retrovirus (retro-iPSCs) and successfully differentiated retinal cells from them, including rod cells [12]. These cells displayed immunochemical features of ER stress and underwent degeneration in vitro. However, retroviral DNAs demonstrated a high probability of random integration into the host cell genome, which can produce unpredictable interruption of genome function and thereafter influence the effects of disease-modeling. To address this issue, in the present study, we used SeV to generate integration-free iPSCs derived from a patient with the RHO mutation. We successfully established iPSC lines and found evidence of ER stress in differentiated rod cells. These results support those of our previous study on patient-derived iPSCs for disease modeling of retinal degeneration.

So far, few studies of patient-derived iPSCs used for in vitro modeling of retinal diseases have been reported. We previously generated iPSCs from patients with RP, a disease primarily characterized by degeneration of the sensory retina [12]. Most recently, Meyer et al. [13] successfully established iPSCs from a patient with gyrate atrophy, a retinal degenerative disease affecting the RPE. In both studies, disease modeling and drug screening were successfully accomplished. Howden et al. [18] demonstrated successful gene correction in the iPSCs derived from a patient via bacterial, artificial chromosome-mediated, homologous recombination. Using this iPSC line, Meyer et al. [13] confirmed that the disease phenotype had been corrected. These studies strongly indicate the utility of disease modeling using patient-specific iPSCs.

The ER is known to dispatch many important signals to the nucleus in eukaryotes. ER stress is a set of pathways that are activated in response to accumulated unfolded proteins in the ER, known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). Under such conditions, the ER chaperone BiP/GRP78 accumulates in the ER and the proapoptotic protein CHOP is upregulated. It has been demonstrated that ER stress-mediated apoptosis is involved in RHO-mutated cells [19].

Because of the unavailability of patient-specific cells, in the past, nonrod cells with forced expression of mutated RHO have been used as a cell model. In the present study, we showed that rod cells derived from an RP patient expressed BiP and CHOP, indicating that ER stress is related to the RHO mutation. It is thus reasonable to hypothesize that misfolded RHO proteins, accumulated in the ER, may trigger UPR-mediated apoptosis in the diseased retina.

Directed differentiation of retinal cells from iPSCs in vitro mimics retinal development during embryogenesis. As both the neural retina and the RPE develop from neural ectoderm via blockade of bone morphogenetic protein, Nodal, and Wnt signals, in vitro induction of retinal cells from iPSCs can succeed using a similar strategy [20]. Osakada et al. [9] established the SFEB culture method to induce the differentiation of mature rod cells expressing the specific protein RHO. In the present study, we generated patient-specific rod cells derived from nonintegrative iPSCs using this method. Most recently, Eiraku et al. [21] successfully generated an optic cup and laminated retina in a three-dimensional culture from murine ESCs. Meyer et al. [13] isolated retinal progenitor cells from early forebrain populations in a human iPSC culture and also obtained optic vesicle-like structures in a three-dimensional culture dish. Our results also suggested an optic-cup morphogenesis and a hint of retinal neuron localization in the culture dish. These new methods may enable us to evaluate patient-specific, self-organized retinal tissue derived from iPSCs in the near future.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrated, for the first time, that integration-free iPSCs derived from an RP patient with the RHO-G188R mutation can be generated and proved that patient-specific iPSCs can be differentiated into retinal cells. In addition, the patient-specific rod cells displayed typical ER stress features and recapitulated the disease phenotype in vitro. These results not only support our previous study using the retroviral method, but also indicate a potential role for patient iPSCs as a model of ER stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DNAVEC Corporation for providing the Sendai virus. This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (#H21-Nanchi-Ippan-216), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81170879), and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security Grant for Returned Oversea Scholars.

Author Contributions

Z.-B.J.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; S.O.: collection and/or assembly of data; P.X.: data analysis and interpretation; M.T.: conception and design, provision of study material or patients, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boucherie C, Sowden JC, Ali RR. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for generating photoreceptors. Regen Med. 2011;6:469–479. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland TJ, Buchholz DE, Clegg DO. Pluripotent human stem cells for the treatment of retinal disease. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:457–466. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osakada F, Hirami Y, Takahashi M. Stem cell biology and cell transplantation therapy in the retina. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2010;26:297–334. doi: 10.5661/bger-26-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishikawa S, Goldstein RA, Nierras CR. The promise of human induced pluripotent stem cells for research and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nrm2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamanaka S. A fresh look at iPS cells. Cell. 2009;137:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha K, Jaenisch R. Technical challenges in using human induced pluripotent stem cells to model disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda H, Osakada F, Watanabe K, et al. Generation of Rx+/Pax6+ neural retinal precursors from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11331–11336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osakada F, Ikeda H, Mandai M, et al. Toward the generation of rod and cone photoreceptors from mouse, monkey and human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:215–224. doi: 10.1038/nbt1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirami Y, Osakada F, Takahashi K, et al. Generation of retinal cells from mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;458:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osakada F, Jin ZB, Hirami Y, et al. In vitro differentiation of retinal cells from human pluripotent stem cells by small-molecule induction. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3169–3179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin ZB, Okamoto S, Osakada F, et al. Modeling retinal degeneration using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer JS, Howden SE, Wallace KA, et al. Optic vesicle-like structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells facilitate a customized approach to retinal disease treatment. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1206–1218. doi: 10.1002/stem.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, et al. Efficient generation of transgene-free human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature-sensitive Sendai virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14234–14239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103509108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osakada F, Ikeda H, Sasai Y, et al. Stepwise differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into retinal cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:811–824. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin ZB, Mandai M, Yokota T, et al. Identifying pathogenic genetic background of simplex or multiplex retinitis pigmentosa patients: a large scale mutation screening study. J Med Genet. 2008;45:465–472. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.056416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet. 2006;368:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howden SE, Gore A, Li Z, et al. Genetic correction and analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells from a patient with gyrate atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6537–6542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103388108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung CH, Davenport CM, Nathans J. Rhodopsin mutations responsible for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Clustering of functional classes along the polypeptide chain. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26645–26649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osakada F, Takahashi M. Neural induction and patterning in Mammalian pluripotent stem cells. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10:419–432. doi: 10.2174/187152711795563958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eiraku M, Takata N, Ishibashi H, et al. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]