Abstract

Objective

While the adverse effect of Major Depressive Episode on role functioning is well established, the exact pathways remain unclear.

Method

Data from The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders, a cross-sectional survey including 21 425 adults from six European countries, were used to assess 12-month depression (Composite International Diagnostic Interview), activity limitations and role functioning in the past 30 days (Disability Assessment Schedule). An a priori model based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health was designed and a structural equation model for categorical and ordinal data was used (MPlus) to estimate the extent to which six limitations mediated the association between depression and role functioning.

Results

The unadjusted association between depression and role functioning was strong (0.43; SE = 0.04). In the best-fitting model, only concentration and attention problems and embarrassment mediated a significant amount of association (direct effect dropped to 0.17; SE = 0.10, which was no longer significant).

Conclusions

Targeting cognition and embarrassment in treatment could help reduce depression-associated role disfunctioning.

Keywords: depression, functional limitations, general population, role functioning

Introduction

Major depressive episode (MDE) is common with lifetime prevalence ranging from 3.0% in Japan to 16.9% in the United States (1) and the burden in terms of limitations in everyday functioning is staggering. Apart from the difficulties at the individual level (2), the societal costs of MDE include work loss (3–5), reduced labour force participation and earning (6–10) and the utilization of health and support services (11). While the adverse effect of MDE on role functioning at home and in paid employment is well established, the exact pathways remain unclear.

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) identifies three aspects of functioning: (i) body functions and structures, (ii) activities and (iii) participation (12). Disability similarly denotes a decrement in functioning at one or more of these levels: (i) impairment, e.g. MDE and related energy and motivation problems; (ii) activity limitation and (iii) role functioning, including role functioning at home and in paid employment. A possible explanation of how MDE may lead to reduced role functioning is that MDE may cause activity limitations which in turn result in role functioning (including reduced role functioning).

At least six activity limitations are distinguished in the ICF: (i) ‘Mobility such as standing and moving around; (ii) ‘Self-care’ such as getting dressed; (iii) ‘Cognition’ which encompasses concentration, attention and memory; (iv) ‘Social Interaction’ i.e., to the ability to engage in social activities; (v) ‘Discrimination’ which refers to discrimination or experiences of unfair treatment; and (vi) ‘Embarrassment’ which encompasses feelings of shame. The six activity limitations (further collectively denoted as ‘limitations’) will be assessed using the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS), specially designed to fit the ICF.

To assess possible mediating effects of limitations upon role functioning at home and in paid employment, the following requirements have to be met: (i) the mediating variables must precede role functioning (the outcome) but follow the onset of the MDE (determinant) and (ii) when limitations are modelled as mediators, the direct association between MDE and role functioning weakens or disappears (13). Our main hypothesis was that the observed association between MDE and role functioning is mediated by limitations. The extent of mediation may well depend on whether or not MDE is comorbid with other mental or physical disorders, as comorbidity is also known to cause limitations and role functioning. In a previous report, we demonstrated substantial role functioning in individuals with a 12-month prevalence of MDE (14). A major strength of this study is that the proposed model is compatible with the ICF which has been accepted by 191 countries as the international standard to describe and measure health and disability. ICF puts all disease and health conditions on an equal footing irrespective of their cause (press release WHO, November 2001). Therefore, the proposed model may also be applicable to diseases as mild as a common cold or as severe as heart disease or AIDS. In this study, we will describe the model for MDE.

Aims of this study

The current study evaluates which limitations mediate in the relation between depression and role functioning. Additionally, the current study addresses which activity limitations mediate most of the effect and how robust the findings, especially across different levels of mental and physical comorbidity, were.

Material and methods

In this cross-sectional study, data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) were used. ESEMeD is part of the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (15). A detailed description of the methods of the study, including sampling frame and weighting procedure, has been presented elsewhere (16). In brief, ESEMeD is a cross-sectional survey representative of the adult population of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. In total 21 425 individuals aged 18 years and older, residing in private households, were interviewed between January 2001 and July 2003. The overall response rate of the study was 61.2%, ranging from 45.9% in France to 78.6% in Spain. The ethics committees in each participating country approved the procedures and informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

The survey interview

The Computer-Assisted Personal Interview used in ESEMeD is subdivided in sections. For the purpose of this study, the following sections are relevant: screening section, Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3 (CIDI-3.0), physical disorders section, role functionings and activity limitations.

Screening section

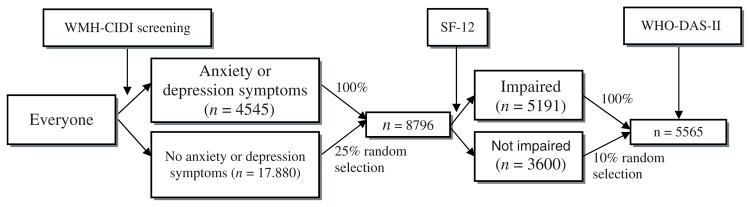

The screening section, located at the beginning of the interview, was administered to all respondents (see Fig. 1). Individuals who could be considered as ‘high-risk individuals’ based on their anxiety or depression symptoms as well as a random subsample (25%) of the respondents without symptoms (low-risk individuals) followed the long path of the interview. The remaining 75% of the respondents without symptoms followed the short path of the interview and are not considered in this study.

Fig. 1.

Composition of the study sample, i.e. respondents who were administered questions about activity limitations and role functioning (the ESEMeD WHODAS). All analyses were weighted to produce estimates of statistics that would have been obtained if the entire sampling frame had participated and to restore the relative size of each country’s general population.

In addition, individuals were screened using the SF-12 (17) which addresses problems in normal daily activities, pain and moving around because of physical and emotional problems. Individuals indicating no problems in these areas were considered ‘low impaired’, and individuals indicating problems in at least one area were considered ‘impaired’. Role functioning and activity limitations were assessed in 100% of those who followed the long path of the interview and were classified as ‘impaired’ (n = 5191) and 10% (n = 374) of the respondents that followed the long path of the interview and were classified as ‘low impaired’ (Fig. 1). All respondents had a known probability of selection so we were able to weigh the data to produce estimates of statistics that would have been obtained if all 21 425 respondents would have answered the questions.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3

For ESEMeD and the WMH Surveys, a further enhanced version of the CIDI, called CIDI-3.0, was developed and adapted by the Coordinating Committee of the WHO–WMH 2000 Initiative (18). The CIDI-3.0 was first produced in English and underwent a rigorous process of forward and back translations to obtain conceptually and cross-culturally comparable versions in each of the target countries and languages. The CIDI is a comprehensive, fully structured diagnostic interview for the assessment of mental disorders. For the purpose of this study, 12-month diagnosis according to the DSM-IV for MDE was used. Furthermore, 12-month diagnoses for dysthymia, agoraphobia, simple phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence were used to establish comorbidity.

Physical disorders

European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders included a checklist of 19 common physical disorders that was administered in a face-to-face interview. The respondents were asked whether they had been diagnosed by a medical doctor as having arthritis or rheumatism, seasonal allergies, stroke, heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma, tuberculosis, other chronic lung diseases, malaria or another parasitic disease, diabetes or high blood sugar, an ulcer in their stomach or intestine, thyroid disease, neurological problem, HIV, AIDS or cancer in the 12 months prior to the interview or received any treatment for these disorders. For the analyses, a dichotomous variable was created: respondents without any physical disorder scored ‘0’ and respondents with at least one physical disorder scored ‘1’ on the new variable.

Role functioning

The ESEMeD-WHODAS assessed ‘role functioning at home and in paid employment’ (Cronbach’s α = 0.71) with three questions: ‘Beginning yesterday and going back 30 days, how many days out of the past 30 were you (i) totally unable to work or carry out your normal activities; (ii) able to work, but had to cut down on what you did or not get as much done as usual; and (iii) able to work, but had to cut back on the quality of your work or how carefully you worked because of problems with either your physical health, your mental health, or your use of alcohol or drugs?’ The scoring rule used in all WHO WMH surveys is that each day out of role (question 1) was assigned a score of 1, each day of cutback in quantity (question 2) and each day of cutback in quality (question 3) was assigned a score of 0.5. When the empirical score exceeded 30 (a rare occurrence), it was fixed at 30. As the total score was skewed (skewness: 3.0, SE 0.017), we chose to recategorize the variable in four categories: 0 (0 days), 1 (1–7 days), 2 (8–29 days) and 3 (30 days). Hence, the three questions capture ‘role functioning at home and in paid employment’ and is further denoted as ‘role functioning’.

Activity limitations

The ESEMeD-WHODAS assessed limitations in the past 30 days in six domains of functioning. For each domain, a single question addressed frequency, i.e. number of days the limitation was present. A variable number of questions addressed severity, with answers being coded as 1 (none), 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), 4 (severe) or 5 (cannot do). The six domains of functioning were: (i) ‘Mobility’ (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.94) including questions about difficulties with standing for long periods, moving around inside the home and walking long distances; (ii) ‘Self-care’ (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.92), which included questions about difficulties with washing, getting dressed and feeding; (iii) ‘Cognition’ (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.88), which included questions about difficulties with concentration, memory, understanding and ability to think clearly; (iv) ‘Social Interaction’ (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.91), which included questions associated with social interaction with people, maintaining a normal social life and participating in social activities; (v) ‘Discrimination ‘ (1 item) ‘how much discrimination or unfair treatment did you experience because of your health problems during the past 30 days’; and (vi) ‘Embarrassment’ (1 item) ‘how much embarrassment did you experience because of your health problems during the past 30 days’. For the first four scales, the crude scores on frequency and severity were normed to a 0–100 metric. The two measures were then multiplied and normed again to a 0–100 metric. As most respondents (88% on Mobility, to 98.5% on Discrimination) reported no limitations, this led to very skewed scales. We, therefore dichotomized all scales in such a way that anyone who scored ‘0’ on the original scale, still scored ‘0’ on the new scale and anyone who scored above ‘0’, scored ‘1’ on the new scale.

Discriminatory validity and internal consistency of the ESEMeD-WHODAS are acceptable and the factor structure is robust over Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean countries (19). for all frequency items, missing data (<5%) were imputed with the mean of non-missing data. For severity items, respondents who gave ‘refuse’ or ‘don’t know’ responses to individual items were imputed ‘mild’ problems and missing data (<5%) were assigned a score of zero to give conservative estimates of problems in functioning.

Statistical analyses

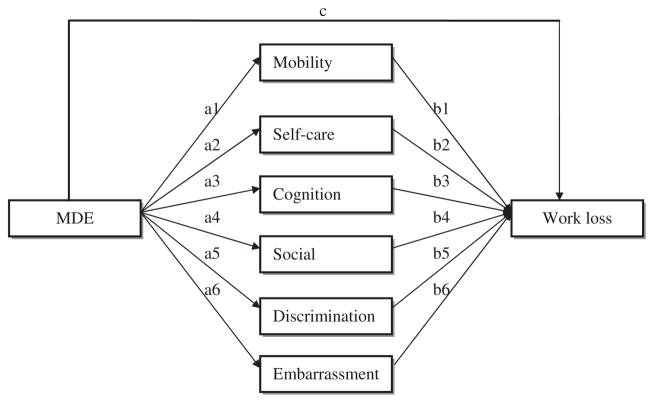

Structural equation models for categorical and ordinal data were used to estimate the extent to which limitations mediated the association between MDE and role functioning. We first estimated a fully saturated model (Fig. 2) in which all six limitations were (i) allowed to mediate between MDE and role functioning (the a1–6 and b1–6 paths) and (ii) to be mutually associated (not depicted in Fig. 2). Subsequently, alterations to this model were tested in the following steps:

Fig. 2.

The fully saturated mediation model (mutual associations between de mediators not depicted). Arrows represent the associations between MDE and activity limitations (a1–a6), the associations between activity limitations and role functioning (b1–b6) and the direct association of MDE and role functioning (c).

The independent path from MDE to role functioning was forced to zero, to evaluate whether the association of MDE and role functioning was fully accounted for by the mediating limitations;

We simplified the model by forcing non-significant path coefficients to zero, starting in a step-wise procedure with the weakest path between MDE and limitations. Next, the non-significant path coefficients between limitations and role functioning were forced to zero in a step-wise fashion;

To establish the robustness of the model, we tested its invariance across four subgroups of respondents composed on the basis of comorbidity.

Descriptive statistics, information about the precision of parameter estimates (and their explained variance), as well as model fitting were accomplished by the SEM program Mplus version 3.11 using the method of maximum likelihood (20).

Differences in fit function between submodels were evaluated by their chi-squared test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Because the proposed models are nested (i.e. all of one model’s free parameters are a subset of the other model’s free parameters), chi-squared difference tests can be performed to compare the fit of nested models. When the chi-squared difference test is non-significant it indicates that a simplified (more restrictive) model does not fit worse than the comparison model and should be preferred. However, with a large sample size, as in this study, even trivial discrepancies between model and data can give large chi-squared test values, significant P values and false model rejection. Therefore, the CFI and RMSEA of each model are also given as they provide sample size adjusted estimates.

All analyses were weighted to produce estimates of statistics that would have been obtained if the entire sampling frame had participated and to restore the relative size of each country’s general population.

Results

Table 1 presents prevalence rates for MDE (past 12 months), limitations and role functioning. The proportion of persons with more than 7 days of role functioning was 11.6% for the total sample and 20.8% for persons with MDE. The prevalence of limitations ranged from 1.5% for Discrimination to 11.9% for Mobility in the total group. Cognition, Social Interaction and Embarrassment were five-to-eight fold increased in the subgroup of persons with MDE vs. a two-to-three fold increase for Mobility and Self-care.

Table 1.

Prevalence of MDE, activity limitations and role functioning in ESEMeD (weighted estimates)

| Number of people | Percentage of total (n = 21 425) (%) | Percentage of 12-month MDE (n = 847) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12-Month MDE | 847 | 4.0 | Not applicable |

| Mobility | 2543 | 11.9 | 27.1 |

| Self-care | 621 | 2.9 | 8.5 |

| Cognition | 1056 | 4.9 | 29.0 |

| Social interaction | 560 | 2.6 | 17.3 |

| Discrimination | 328 | 1.5 | 12.4 |

| Embarrassment | 1207 | 5.6 | 24.9 |

| Role functioning (days) | |||

| 0 | 17 119 | 79.9 | 46.8 |

| 1–7 | 1813 | 8.5 | 32.4 |

| 8–29 | 1799 | 8.4 | 11.6 |

| 30 | 683 | 3.2 | 9.2 |

MDE, major depressive episode; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders.

Table 2 presents the standardized coefficients of the paths linking MDE to limitations (first column) and the latter to role functioning (second column) in the fully saturated model (Table 2). Removal of the direct effect of MDE on role functioning (0.17, SE = 0.06) significantly decreased the fit of the model (Δχ2 = 9.2, df = 1, P = 0.002, CFI: 0.995, RMSEA: 0.038), indicating that some but not all of the association between MDE and role functioning is mediated by the limitations.

Table 2.

Standardized path coefficients estimated in the fully saturated model†

| Paths (and SE) from MDE to limitations (a1–a6) | Paths (and SE) from limitations to role functioning (b1–b6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | 0.10(0.08) | 0.27(0.06)* |

| Self-care | 0.18(0.11) | 0.11(0.08) |

| Cognition | 0.63(0.08)* | 0.19(0.05)* |

| Social Interaction | 0.64(0.09)* | 0.07(0.07) |

| Discrimination | 0.58(0.10)* | 0.02(0.07) |

| Embarrassment | 0.52(0.09)* | 0.09(0.07) |

Note: CFI 1.000 and RMSEA 0.000.

Path from MDE to role functioning, estimating the remaining direct effect of MDE on role functioning, was 0.17 (0.06).

CFI, Comparative Fit Index; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders; MDE, major depressive episode; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

Statistical significance at P < 0.05.

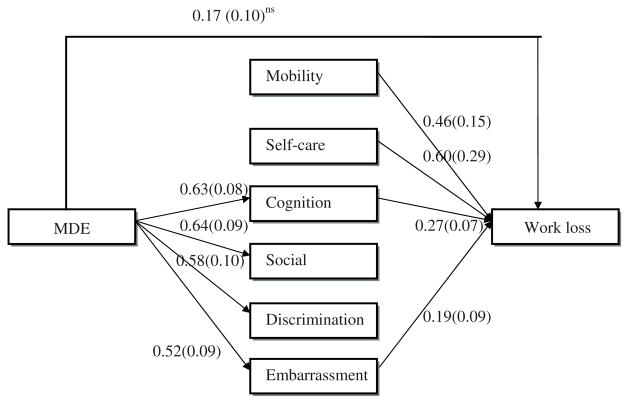

The fully saturated model was then simplified as described in the Analysis section of the Methods. The resulting model (Fig. 3) fitted the data well compared with the fully saturated model (Δχ2 = 4.68, df = 3, P = 0.20, CFI: 0.999, RMSEA: 0.010).

Fig. 3.

The final model (CFI = 0.999, RMSEA: 0.010; Δχ2 = 4.68, df = 3, P = 0.20). Path coefficients represent standardized partial regression coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses).

The standardized path coefficients in Fig. 3 show that only Cognition and Embarrassment were significantly associated with both MDE and role functioning, and thus mediating association between MDE and role functioning. Although MDE was strongly related to Social Interaction and Discrimination and role functioning to Self-care and Mobility, none of these four limitations mediated any association between MDE and role functioning. The effect of Mobility and Self-care on role functioning is independent of MDE and probably because of physical disorders.

The direct effect of MDE on role functioning according to the final model amounted to 0.17 (SE = 0.10), compared with the 0.43 (SE = 0.04) from the path model without the six mediating limitations. Constraining the direct effect of MDE on role functioning to zero significantly worsened the fit of the model (Δχ2 = 11.95, df = 4, P = 0.002; CFI: 0.993, RMSEA: 0.024). The difference between the total effect (0.43) and the direct effect (0.17) suggest that about half of the total effect is indirect, i.e. mediated by Cognition and Embarrassment.

The final model (Fig. 3) was then fitted in four subgroups: (i) persons without any other disorder than MDE (n = 1662), (ii) persons with one or more non-MDE mental disorders (i.e. anxiety disorders or alcohol related disorders), but not a physical disorder; n = 257), (iii) persons with physical disorders, but not a mental disorder other than MDE (n = 2986), and (iv) persons with both non-MDE mental disorders and physical disorders (n = 660). The strength of the significant paths from the final model (a3–a6, b1–b3, b6 and c) could not be constrained to be equal across the four subgroups without significant loss of fit. However, if the strength of these paths was allowed to differ between subgroups, the final model had a good overall fit (CFI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.005; χ2 = 15.15, df = 15, P = 0.42). Thus, the mediation model is robust as it was independent of whether or not MDE was comorbid with other mental and/or physical disorders.

Discussion

This study found that approximately half of the impact of MDE on role functioning was mediated by problems with Cognition and by feelings of Embarrassment. These limitations resulted in a six-to-eight fold increase compared with persons without MDE in the past 12 months. To our knowledge, this mediation has not been addressed previously. Consequently, interventions aimed at improving cognition and reducing embarrassment may relieve personal suffering associated with MDE and could also positively influence the societal effects of MDE by reducing role functioning. Targeting these mediating limitations might be especially valuable when depression occurs in the context of neuropsychological impairments. Such impairments as measured by simple neuropsychological tests as verbal fluency, block design and so on, in depressed patients predict an unfavourable outcome of antidepressant therapy (21) and cognitive behaviour therapy (22). Thus, improvement of concentration and attention may lead to decreased role functioning and might also improve the effectiveness of antidepressive treatment. With respect to other mental disorders, neurocognitive training has already yielded such positive effects. For instance, in brain damaged patients, general improvement of cognitive functions (including attention) was accompanied with better ability to manage common social situations and development of compensatory strategies (23, 24). Embarrassment is related to a negative evaluation of oneself and limits the ability to engage in effective social interaction. Patients suffering from MDE may be at particular risk to be embarrassed about their condition because of self-stigmatization (25, 26). Stigma in the context of MDE is associated with greater unmet mental health care needs (26), and predicts antidepressant drug non-compliance (27) and treatment discontinuation (28). Embarrassment may therefore be a useful target for intervention with the aim of improving treatment adherence, outcomes and consequences of MDE.

This study has strengths and weaknesses. Its major strength is that the model is compatible with the ICF which is the international standard to describe and measure health and disability. While the current application of the model was limited to MDE, the model can easily be applied to other mental and physical disorders. The model may thus be valuable in comparing the limitation pathways of any disorder via which they affect role functioning and other major outcomes. An additional strength is the large representative cross-national sample which ensures generalizability across six European countries. However, seven limitations should be mentioned as well. First, the mediators and the outcome come from the same instrument which may have induced information contamination bias. A related, and potentially more problematic issue, is that data were cross-sectional which prohibits firm conclusions about time order and causation, although the time order that we assumed between MDE, limitations, and role functioning makes conceptually more sense than the other way around (29–31). Furthermore, the association between limitations and role functioning did not change much when controlling for MDE whereas the association between MDE and role functioning weakened substantially after controlling for limitations. Thus, a causal relation from MDE through limitations to role functioning is more likely than vice versa. The second limitation is that the assessment of limitations and role functioning relied heavily on respondents’ memory and perception. These problems lead to measurement error which will deflate associations. On the other hand, depressed individuals might tend to give pessimistic appraisals which would inflate associations. A third limitation is that MDE was determined using the CIDI, which is administered by lay interviewers. CIDI diagnoses have acceptable reliability and validity (32), but have shown some variance with diagnoses made by clinicians (33). Fourth, the prevalence of Social interaction problems was low in those with a 12-month prevalence of MDE. This could mean that MDE does not strongly impair social interaction, but it might also be because of the threshold implied in the wording of the screening question in the Social Interaction section. It is also possible that some people tend to consider social interaction difficulties as unrelated to ‘health problems’ if they are because of mental illness, even in the context of a psychiatric interview that stressed at multiple occasions that mental health is part of overall health and that the word health refers to both physical and mental health. Fifth, it may be argued that cognition is a symptom of depression rather than a mediating mechanism. We believe this may partly be so, although cognition is differently conceptualized in WHODAS than in the DSM-IV. Moreover, to the extent that it is regarded as a depression symptom, our findings then suggest that this symptom is particularly important for producing negative effects on role functioning and should be considered a target of intervention. Two final limitations concern the temporal and causal structure amongst the activity limitations and their comprehensiveness. Our current approach allowed the limitations to correlate and did not specify restrictive causal relationships amongst the limitations. The limitations, however, might be causally related in a highly specific way. For instance, cognition problems, caused by MDE, might precede and influence social interaction which itself may not be causally affected by MDE. While we do not think that different causal structures will yield much different mediation effects, some dependency on how the limitations influence one another cannot be ruled out.

Despite the study limitations, we found that cognition and embarrassment accounted for half the association between MDE and role functioning. We firmly recommend that this study will be replicated using longitudinal data. If confirmed, it suggests that interventions aimed at improving Cognition and reducing Embarrassment may relieve personal suffering associated with MDE and could also positively influence the societal effects of MDE by reducing role functioning.

Significant outcomes.

Depression has a strong negative effect on role functioning.

Approximately half of the impact of depression on role functioning is mediated by cognition and feelings of embarrassment.

The observed mediation is robust as it was independent of whether or not depression was comorbid with other mental and/or physical disorders.

Limitations.

Cross-sectional data.

Data was collected using self-report.

No restrictive causal relationships amongst limitations were specified.

Acknowledgments

The survey discussed in this article was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., Glaxo-SmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline and a personal grant from GlaxoSmithKline Netherlands. The abovementioned providers of funding had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in de decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no competing interests with this study.

References

- 1.Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:3–21. doi: 10.1002/mpr.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buist-Bouwman MA, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W, et al. Functional disability of mental disorders and comparison with physical disorders. A study among the general population of six European countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goering P, Lin E, Campbell D, Boyle M, Offord D. Psychiatric disability in Ontario. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:564–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Frank R. The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychol Med. 1997;27:861–873. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouzis A, Eaton W. Emotional disability days: prevalence and predictors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1304–1307. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broadhead W, Blazer D, George L, Tse C. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti D, Burton W. The economic impact of depression in a work place. J Occup Med. 1994;36:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg P, Stiglin L, Finkelstein S, Berndt E. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267:1478–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stansfeld S, Feeney A, Head J, Canner R, North F, Marmot M. Sickness absence for psychiatric illness: the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouzis A, Eaton W. Psychopathology and the development of disability. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:379–386. doi: 10.1007/BF00788177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraemer H, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The ESEMeD /MHEDEA 2000 investigators. Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigators. Sampling and methods of the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigators. The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000) project: rationale and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2002;11:55–67. doi: 10.1002/mpr.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler R, Ustun T. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, De Graaf R, et al. Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule used in the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008 doi: 10.1002/mpr.261. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kampf-Sherf O, Zlotogorski Z, Gilboa A, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in major depression and responsiveness to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors antidepressants. J Affect Disorders. 2004;82:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crews W, Jr, Harrison D. The neuropsychology of depression and its implications for cognitive therapy. Neuropsychol Rev. 1995;5:81–123. doi: 10.1007/BF02208437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson IH. Cognitive neuroscience and brain rehabilitation: a promise kept. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:357. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson IH, Murre J. Rehabilitation of brain damage: brain plasticity and principles of guided recovery. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:544–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolpert L. Stigma of depression – a personal view. Br Med Bull. 2001;57:221–224. doi: 10.1093/bmb/57.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roeloffs C, Sherbourne C, Unutzer J, Fink A, Tang LQ, Wells KB. Stigma and depression among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:479–481. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W. Functioning after a major depressive episode: complete or incomplete recovery? J Affect Disorders. 2004;82:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, et al. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:375–380. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ormel J, Oldehinkel A, Nolen W, Vollebergh W. Psychosocial disability before, during, and after a major depressive episode: a 3-wave population-based study of state, scar, and trait effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:387–392. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brugha TS, Jenkins R, Taub N, Meltzer H, Bebbington P. A general population comparison of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) Psychol Med. 2001;31:1001–1013. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]