Abstract

We have recently reported that early maternal deprivation (MD) for 24 h [postnatal day (PND) 9–10] and/or an adolescent chronic treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP-55,940 (CP) [0.4 mg/kg, PND 28–42] in Wistar rats induced, in adulthood, diverse sex-dependent long-term behavioral and physiological modifications. Here we show the results obtained from investigating the immunohistochemical analysis of CB1 cannabinoid receptors, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) positive (+) cells and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the hippocampus of the same animals. MD induced, in males, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in CA1 and CA3 areas and in the polymorphic layer of the dentate gyrus (DG), an effect that was attenuated by CP in the two latter regions. Adolescent cannabinoid exposure induced, in control non-deprived males, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in the polymorphic layer of the DG. MD induced a decrease in CB1 expression in both sexes, and this effect was reversed in males by the cannabinoid treatment. In turn, the drug “per se” induced, in males, a general decrease in CB1 immunoreactivity, and the opposite effect was observed in females. Cannabinoid exposure tended to reduce BDNF expression in CA1 and CA3 of females, whereas MD counteracted this trend and induced an increase of BDNF in females. As a whole, the present results show sex-dependent long-term effects of both MD and juvenile cannabinoid exposure as well as functional interactions between the two treatments.

Keywords: maternal deprivation, adolescent cannabinoid exposure, CB1 cannabinoid receptor, GFAP, BDNF, sex differences

Traumatic experiences during early developmental periods might be associated with psychopathology (such as depression or schizophrenia) and altered neuroendocrine function later in life (Levine, 2005; Moffett et al., 2007; Tyrka et al., 2008). Several experimental models attempt to mimic diverse types of early-life stress. Notably, rats submitted to a single 24-h episode of maternal deprivation (MD) at postnatal day (PND) 9 exhibit, as adults, behavioral abnormalities resembling psychotic-like symptoms, including disturbances in pre-pulse inhibition, latent inhibition, auditory sensory gating and startle habituation. Possible underlying neurochemical correlates in adult MD animals include reduced hippocampal levels of neuropeptide Y (NPY), calcitoningene-related peptide, polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and a decrease in NMDA receptor subunits NR-2A and NR-2B (see for review (Ellenbroek and Riva, 2003; Ellenbroek et al., 2004)). In addition, adolescent MD rats showed depressive-like behaviors and altered responses to a cannabinoid agonist (Llorente et al., 2007), as well as a trend towards increased impulsivity (Marco et al., 2007). We have also shown that MD induced neuronal degeneration and increased number of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)+ cells in the hippocampus and cerebellar cortex of neonatal rats. Interestingly, these effects were often more marked in males. MD also produced an enduring decrease in leptin and an increase in corticosterone for both sexes (López-Gallardo et al., 2008; Llorente et al., 2008, 2009; Viveros et al., 2009). These alterations support our hypothesis that the neonatal stress accompanying MD may be a useful model to examine behavioral symptoms with a neurodevelopmental etiology.

The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is a key component of the endocannabinoid system (ECS). The ECS consists of endogenous ligands called endocannabinoids, typically anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG), which activate cannabinoid receptors (primarily CB1 and CB2 receptors, respectively). The CB1 receptor is the predominant cannabinoid receptor within the central nervous system, and is highly expressed in brain regions involved in emotional processing, motivation, motor activation and cognitive function (Mackie, 2005). Among the multiple functions of the endocannabinoid system (Viveros et al., 2005, 2007; Wotjak, 2005; Cota, 2008; Moreira and Lutz, 2008; Bermudez-Silva et al., 2010) it also plays a role in neural development (Keimpema et al., 2011).

Previously we found that neonatal MD animals had increased levels of 2-AG and decreased CB1 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus, with these alterations being more marked in males (Llorente et al., 2008; Suárez et al., 2009). Concordant with increased 2-AG levels, we recently found that MD also significantly decreased hippocampal monoacylglycerol lipase, the major 2-AG degrading enzyme, as reflected by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. This decrease, again, was more marked in males than in females (Suárez et al., 2010). Moreover, two inhibitors of endocannabinoid inactivation modulated the above-indicated cellular effects induced by MD stress (Llorente et al., 2007). As a whole, these data support a clear association between neurodevelopmental MD stress and dysregulation of the ECS.

Adolescence represents a critical phase in development during which the nervous system shows a unique plasticity. During this period, maturation and rearrangement of major neurotransmitter pathways are still taking place (Spear, 2000; Romeo, 2003; Laviola and Marco, 2011) including the endocannabinoid system (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1993; Viveros et al., 2011a, b). The ages associated with adolescence are commonly considered to be approximately between 12 and 20–25 years in humans and around PND 28–42 in rodents (Spear, 2000; Adriani and Laviola, 2004). The early adolescent period has been identified as a phase of development particularly vulnerable to some of the adverse effects of exposure to cannabinoid compounds. Notably, in predisposed people, early exposure to cannabis increases the risk of developing schizophrenia and may exacerbate symptoms in psychotic patients (Di Forti et al., 2007; Leweke and Koethe, 2008; Fernandez-Espejo et al., 2009; Sewell et al., 2009). In addition, both human and animal studies indicate that cannabis use during adolescence, perhaps in a sex-dependent fashion, may produce additional negative effects such as cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms and increased risk of further developing substance-abuse disorders (Sundram, 2006; Rubino et al., 2008; Schneider, 2008; Fernandez-Espejo et al., 2009; Wegener and Koch, 2009; Viveros et al., 2011a, b).

Despite neonatal MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure having been demonstrated to induce important long-lasting behavioral and neuroendocrine effects, the combination of the two treatments has been scarcely investigated (Macrì and Laviola, 2004; Llorente-Berzal et al., 2011). In our recent study on this topic (Llorente-Berzal et al., 2011), the psychophysiological effects of MD and/or adolescent exposure to CP-55,940 (CP) were studied at adulthood. MD induced a compensatory increase in maternal behavior after reunion with the dam and, in the long-term, we observed, in males, an increase of open-arm exploration in an elevated plus-maze that could be related to risk-taking behavior. Adolescent exposure to cannabinoids exerted more pronounced long-lasting behavioural effects that were evident only in females. The main behavioral alterations consisted in an increased exploration in novel environments (holeboard), which suggests an increase in novelty-seeking and in a decreased prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex, suggestive of an impairment in sensoriomotor gating (attentional processes) that could increase vulnerability to psychiatric disorders such as drug addiction and schizophrenia. The reactivity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis to an intermediate stressor was also studied and results indicated that in males the adolescent treatment with the cannabinoid increased HPA axis response. Thus, overall data supported the view that early MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure exerted distinct sex-dependent long-term behavioural and physiological modifications that could predispose to the development of certain neurobehavioral disorders.

In the present study we have analyzed hippocampal CB1 cannabinoid receptors and GFAP positive (+) cells in the rats used in our recent paper (Llorente-Berzal et al., 2011). Our interest in these parameters and in this specific brain area was based on the following premises: the high density of hippocampal CB1 receptors (Herkenham et al., 1990), intrahippocampal cannabinoids impairs memory (Lichtman et al., 1995), and cannabinoids desynchronize hippocampal neuronal assemblies, possibly accounting for cannabinoid-induced memory impairment (Robbe et al., 2006). Moreover, morphological changes in the hippocampus have been observed following chronic administration of cannabinoids (Lawston et al., 2000; Tagliaferro et al., 2006). We had previously shown that MD induced rapid changes in the number of GFAP+ cells as well as in CB1 receptors in the hippocampus of neonatal rats (PND 13), and here we aimed to investigate whether these changes persisted into adulthood. We have previously found that chronic treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP-55,940, at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg/d (PND 28–43), produced long-term, sex-dependent harmful effects on memory and changes in brain CB1 receptors (Mateos et al., 2010). So, another objective of this study was to investigate possible functional interactions between MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure on these parameters. We also addressed the effects of neonatal MD and the adolescent CP treatment on the expression of BDNF, a molecule known to regulate cell survival and differentiation. Finally, on the basis of our previous findings indicating sex-dependent effects of each treatment (MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure) separately, we expected that the sex of the animals would have an important influence when both treatments were combined.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Animals

Wistar rats obtained from Harlan Interfauna Ibérica (Barcelona, Spain) were used. Females arrived when they were about 7 weeks old and males when they were about 9 weeks old. They were housed in the General Vivarium of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, initially separated by sex in groups of two to three and housed in polypropylene opaque wire-topped cages with solid bottom (21.5×46.5×14.5 cm3; Type “1000 cm2,” Panlab SLU, Barcelona, Spain) containing sawdust bedding (Ultrasorb, Panlab, SLU) and fed with Diet “A04” (Safe-Panlab SLU). Rats were always maintained at standard temperature conditions (21 °C±2) and on a 12–12 h light–dark schedule (lights on at 8:00 AM). The experimental protocol was approved by the Committee of Ethics of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, followed the “Principles of laboratory animal care” and was carried out in accordance with European Communities Council Directive (86/609/EEC).

Subjects and experimental groups

Maternal deprivation was performed on PND 9 for 24 hours as previously described (Llorente et al., 2007). In brief, mothers were removed early in the morning (beginning at 9:00 h, i.e., 1 h after the beginning of the light phase) and pups were weighed and remained undisturbed in their home cages (in the same room as their mothers) for 24 h. On PND 10 mothers were returned to their corresponding cages. Mothers from the control groups were briefly removed from their home cages while the pups were weighed. The adolescent treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 (0.4 mg/kg/d) i.p. or its corresponding vehicle (ethanol: cremophor:saline 1:1:18; Cremophor® EL Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) was performed between PND 28 and 42. The time-interval and length of the treatment and the dose of CP used were chosen on the basis of the above mentioned data from Spear (2000); Rodríguez de Fonseca et al. (1993); Adriani and Laviola (2004) and from previously published data from our laboratory (Biscaia et al., 2003, 2008; Mateos et al., 2010) and others (Higuera-Matas et al., 2008, 2009).

Maternal behavior was assessed for 3 days before and after the maternal deprivation. At adulthood, a battery of behavioral tests was performed consisting of the prepulse inhibition of the startle response (PPI), the holeboard and the elevated plus maze (EPM) tests. After the PPI and the EPM, a blood sample was taken to evaluate the reactivity of the HPA axis. Methodological details and results obtained in this first part of the study are thoroughly explained in Llorente-Berzal et al. (2011).

In the present work, we show the results obtained in the neuroimmunohistochemical study described below, which was carried out on the hippocampi of the animals used for the behavioral analysis. On the basis of maternal manipulation [MD or non MD (Co (Control non deprived animals))] and the adolescent treatment [pharmacological treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP or Vehicle (Vh)], the following experimental groups were formed for each sex: Co-Vh, Co-CP, MD-Vh and MD-CP. In total, we had eight experimental groups with six animals per group.

Tissue collection

Rats were anesthetized with isofluorane at PND 80, and perfused with saline solution (4 °C) for 2 min followed by paraformaldehyde 4% (Merck) and sodium borate 3.8% (4 °C) for 12 min. Then brains were removed and post-fixed overnight at 4 °C. After that, brains were changed to a cryoprotectant solution (0.2 M NaCl, 43 mM potassium phosphate (KPBS) containing 30% sucrose, pH=7.2) for 48 h at 4 °C. Then, brains were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C. From every brain, four series of 20 μm sections from bregma 4.00 to −11.00 mm (Paxinos and Watson, 2007) were obtained using a cryostat (Leica), and stored at −20 °C in an anti-freeze solution (30% ethyleneglycol, 20% glycerol in 0.25 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.3).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed in medial hippocampus, on free-floating sections under moderate shaking. All washes and incubations were done in 0.1 M PB pH 7.4, containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% triton X-100, which constituted the immunohistochemistry buffer (IB). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked for 10 min at room temperature in a solution of 3% hydrogen peroxide in 50% methanol. After several washes in IB, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody and then rinsed in IB and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the secondary antibody.

We evaluated the astroglial reaction by studying changes in the GFAP, the main intermediate filament of astrocytes, as the most adequate marker for the present immunochemical analysis. It defines the astrocytic morphology and it is possible to evaluate the astroglial reaction by studying changes in GFAP expression (Tagliaferro et al., 1997). We used a monoclonal antibody for GFAP as primary antibody [Rabbit anti-GFAP Ig G, 1:1000 dilution (SIGMA, Madrid, Spain, Ref: G9269)] and a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit Ig G as secondary antibody, 1:300 dilution [Healthcare, Madrid, Spain, Ref: RPN, 1004].

For CB1 cannabinoid receptor analysis, a polyclonal antibody for CB1 was used as primary antibody, 1:500 dilution [provided by Dr. Ken Mackie] and a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG as secondary antibody, 1:300 dilution [Pierce, Rockford, USA, Ref: 31820].

In order to evaluate BDNF expression, a polyclonal antibody for BDNF was used as primary antibody, 1:200 dilution [Rabbit polyclonal IgG anti BDNF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA, Ref: sc-546)] and a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG as secondary antibody, 1:300 dilution (GE Healthcare, Madrid, Spain, Ref: RPN 1004V).

After incubations with the specific antibodies, sections were washed several times in IB and then were incubated for 90 min at room temperature with avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (ImmunoPure ABC peroxidase staining kit, Pierce. Rockford, IL, USA, 1:250 dilution). The reaction product was revealed by incubating the sections with 2 μg/ml 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M PB. Then, sections were dehydrated, mounted on gelatinized slides and coverslipped with mounting medium dibutyl phthalate in xylene (DEPEX, Serva, Heidelberg, Germany).

To check the specificity of the immunoreaction, we included control preparations (omitting the primary antibody) in each immunostaining batch. Immunostaining batches containing all the experimental groups as well as the internal control were run for males and females separately. Two different batches were run for each primary antibody and for each animal.

Slides immunostained for GFAP, CB1 or for BDNF were observed in a Zeiss Axioplan Microscope (Germany). The microscope had attached a camera (ZEISS Axiocam), through which the images were captured to be processed using Axiovision 40 V 4.1 (Carl. Zeiss vision GMBH). Panel illustrations were made by mounting the selected images with Adobe Photoshop 8.0, with adjustments of contrast and brightness for faithful reproduction of colors seen in the prints.

Quantitative evaluation of GFAP positive (+) cells

The number of GFAP+ cells was estimated by the optical disector method (Reed and Howard, 1998) using total section thickness for disector height (Hatton and von Bartheld, 1999), and a counting frame size of 0.215 mm of width and 0.26 mm of length. A total number of 20 counting frames were assessed for each animal and each zone analyzed. Section thickness was measured using a digital length gauge device (Heidenhain-Metro MT 12/ND221; Traunreut, Germany) attached to the stage of a Leitz Laborlux 8 microscope. All counts were performed on coded sections.

Quantification of GFAP+ cells was made with the 20× objective. Four tissue sections per animal were analyzed. On each tissue section we focused on CA1 and CA3 areas of Ammon’s horn and on the dentate gyrus (DG). In each of these zones cell nuclei from immunoreactive cells that came into focus, while focusing down through the dissector height, were counted. Data were expressed as number of GFAP+ cells per mm3.

Quantitative evaluation of CB1 and BDNF density

Quantification of CB1 and BDNF immunostaining was carried out on high-resolution digital microphotographs that were taken with the 10× objective and under the same conditions of light and brightness/contrast, by measuring densitometry of the selected areas using the analysis software ImageJ 1.383 (NIH, USA).

Four tissue sections per animal were analyzed. On each tissue section we focused on CA1 and CA3 areas of Ammon’s horn and on the DG. For both CA subfields, we carried out separate densitometrical analysis as follows. For CB1 cannabinoid receptor, we analyzed separately (1) stratum oriens (SO), (2) stratum pyramidale together with radiatum (SR–SP), and (3) stratum lacunosum together with moleculare (SL–M). For DG, we carried out separate densitometrical analysis corresponding to (1) the molecular layer (ml) together with the granular cell layer (gcl) and (2) the polymorphic cell layer. The densitometrical analysis corresponding to BDNF was carried out in stratum radiatum (SR) for CA1 and CA3 areas and for DG in the polymorphic cell layer. All data were expressed in arbitrary units.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with factors being sex, neonatal manipulation and pharmacological treatment. The criterion of normally distributed data were not always met in some populations of this study, so in order to satisfy the assumption of normality for the ANOVA, data were transformed when necessary by the Neperian logarithm function. When appropriate, three-way ANOVAs were followed by separate two-way ANOVA split by one of the independent factors to further clarify the results. Post hoc comparisons were performed with a level of significance set at P<0.05. For data that were normal and homoscedastic, standard parametric post hoc tests were used (Tukey’s test) and for those that were normal but non-homoscedastic, non-parametric post hoc comparisons were performed (Games-Howell’s test). Statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS 19.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

So that the presentation of the high number of statistical data obtained is compatible with the comprehension of the “home take message”, we have organized the result section as follows. For each parameter measured, we first indicate the statistical results and then a summary paragraph highlighting the main results. To avoid an excessive length of the text we have sometimes used abbreviations. It would be useful to the reader to recall here some of them: MD, maternal deprivation; CP, CP55940; Co, Control non deprived animals; Vh, vehicle.

Number of GFAP positive cells

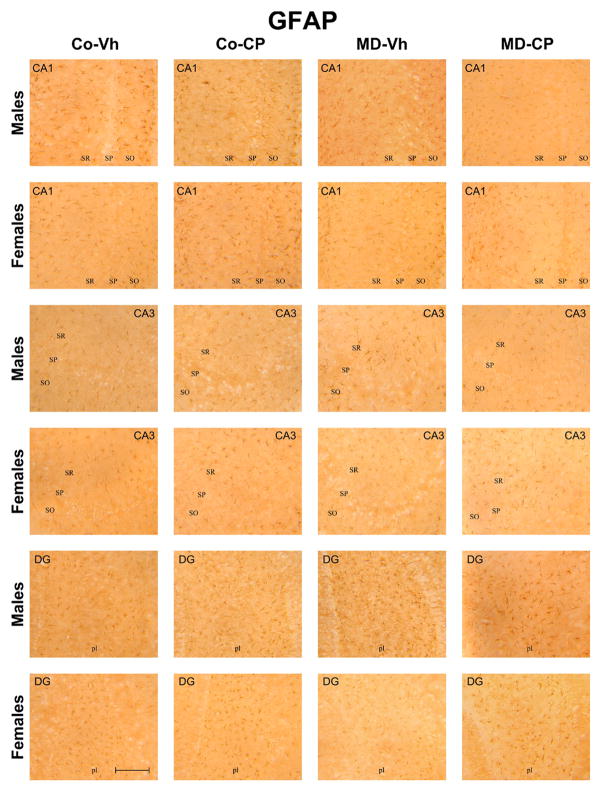

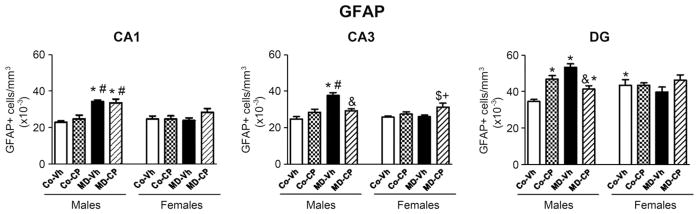

Quantitative results from GFAP immunohistochemistry are represented in Fig. 1. Fig. 2 shows representative microphotographs for the different experimental groups.

Fig. 1.

Effects of maternal deprivation (MD) and/or adolescent exposure to the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 on hippocampal GFAP positive (+) cells of adult male and female rats. Quantification of the number of GFAP positive cells (GFAP+/mm3) was carried out in the CA1 and CA3 areas of the Ammon’s Horn and in the polymorphic layer of the Dentate Gyrus (DG). Histograms represent the mean±SEM of six animals per experimental group. MD, maternal deprivation; Co, control non MD animals; Vh, vehicle (see text); CP, CP 55,940. Significant differences, P<0.05: * vs. CoVh male; # vs. CoCP male; & vs. MDVh male; $ vs. CoVh female; + vs. MDVh female.

Fig. 2.

Representative microphotographs of hippocampal GFAP+ glial cells after maternal deprivation (MD) and adolescent treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 (CP) in CA1, CA3 and Dentate Gyrus (DG) of adult male and female rats. Scale bar 5 μm. MD, maternal deprivation; Co: control non MD animals; Vh: vehicle (see text); CP, CP 55,940; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum; pl, polymorphic layer. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.

In CA1, the three-way ANOVA rendered a significant sex×MD interaction [F(1,49) = 12.72, P<0.05] as well as significant effects of sex [F(1,49) = 8.27, P<0.05] and MD [F(1,49) = 22.70, P<0.05]. Subsequent two-way ANOVA split by sex revealed a significant effect of the MD among males [F(1,25) = 37.34, P<0.05] but it did not show any effect in females. Post hoc comparisons showed a significant increase of GFAP+ cells in maternally deprived males when compared with their control counterparts.

The three-way ANOVA of the number of GFAP+ cells quantified in CA3 rendered significant effects of the triple interaction sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,49) = 14.29, P<0.05] and of two double interactions, that is, sex×MD [F(1,49) = 5.98, P<0.05] and sex×pharmacological treatment [F(1,49) = 6.75, P<0.05] as well as significant effects of sex [F(1,49) = 4.88, P<0.05] and MD [F(1,49) = 19.19, P<0.05]. Subsequent two-way ANOVA split by sex revealed a significant interaction MD×pharmacological treatment in males [F(1,25) = 15.36, P<0.05] as well as a significant effect of MD [F(1,25) = 21.88, P<0.05]. Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in MD animals that was reversed by the cannabinoid agonist treatment. In females the two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of the pharmacological treatment [F(1,24) = 6.65, P<0.05]; MD females treated with CP showed an increase in the number of cells GFAP+ compared with the MDVh female group; while a decrease in the number of cells GFAP+ was observed in MDCP males when compared with MDVh males.

In the DG, the three-way ANOVA revealed the following significant interactions: sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,49) = 23.88, P<0.05], sex×MD [F(1,49) = 5.01, P<0.05] and MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,49) = 8.24, P<0.05]. Two-way ANOVA test split by sex revealed a significant interaction between MD and the pharmacological treatment, [F(1,25) = 47.99, P<0.05] and a significant effect of MD [F(1,25) = 14.14, P<0.05] in males, whereas no significant effects were found in females. Post hoc analyses showed a sexual dimorphism among control animals with females showing a significant higher number of GFAP+ cells than males. In addition, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells due to MD and/or adolescent treatment with the CB1 agonist in males was also revealed and this effect was reversed by CP treatment in maternally deprived males.

To sum up, the number of GFAP+ cells in all experimental groups is higher in the polymorphic cell layer of DG than in CA1 and CA3 areas. Control females exhibited higher basal levels of GFAP+ cells when compared with control males in the polymorphic cell layer of DG. In turn, adolescent treatment with CP induced an increase in the number of GFAP+ cells particularly in the polymorphic cell layer of males DG, whereas no significant effect of CP was found in females. In males, MD induced a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in all the areas analyzed, which was reversed by the CP treatment in CA3 and polymorphic cell layer of DG but not in CA1. However, in females MD per se did not induce any modification in the number of GFAP+ cells.

CB1 receptor

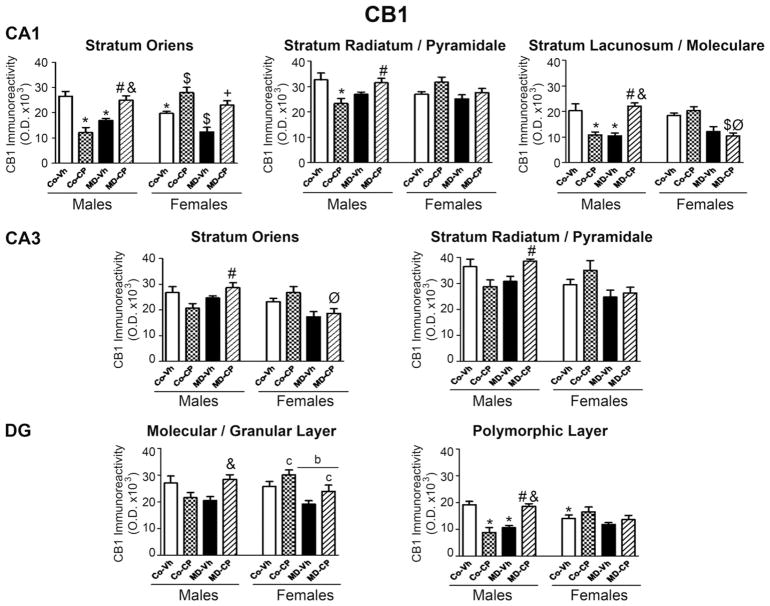

Results corresponding to the quantification of the CB1 receptor immunoreactivity are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of maternal deprivation (MD) and/or adolescent exposure to the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 on hippocampal CB1 cannabinoid receptors expression of adult male and female rats. Quantification of CB1 receptor immunoreactivity was carried out in CA1, and CA3 areas of Ammon’s Horn and in the Dentate Gyrus (DG). Histograms represent the mean±SEM of six animals per experimental group. MD, maternal deprivation; Co, control non MD animals; Vh, vehicle (see text); CP, CP 55,940. ANOVA (P<0.05); b, significant overall effect of maternal deprivation; c, significant overall effect of chronic CP treatment. Significant differences, P < 0.05: * vs. CoVh male; # vs. CoCP male; & vs. MDVh male; $ vs. CoVh female; Ø vs. CoCP female; + vs. MDVh female.

We focused on CA1 and CA3 areas of Ammon’s horn and on the DG. For both CA subfields, we analyzed separately (1) SO, (2) SR–SP and (3) SL–M. For DG, we carried out separate densitometrical analysis corresponding to (1) the ml together with the gcl and (2) the polymorphic cell layer. We have undertaken a detailed analysis of these separate areas and strata in light of previous results of our group (Suárez et al., 2009). These results provided an original description of CB1 distribution within the hippocampus of 13-day-old rats that was in agreement with previous descriptions in adult animals (Egertová and Elphick, 2000). Thus, it seems that at PND 13 the CB1 receptor is already in its final distribution, and for this reason we decided to carry out the same design of analysis in the present study. In SO of CA1 the three-way ANOVA revealed the following significant interactions: sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 18.06, P<0.05], sex×MD [F(1,40) = 10.68, P<0.05], sex×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 28.28, P<0.05] and MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 27.51, P<0.05] as well as a significant effect of the pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 6.82, P<0.05]. In males the two-way ANOVA revealed a significant MD×pharmacological treatment interaction [F(1,20) = 44.86, P<0.05]. In females, the two-way ANOVA rendered significant effects of neonatal MD [F(1,20) = 13.56, P<0.05] and of the pharmacological treatment [F(1,20) = 31.60, P<0.05]. In males, post hoc analyses showed a decrease in the CB1 immunoreactivity due to each treatment (MD and adolescent CP administration) considered separately. However, in the animals receiving both treatments CB1 receptor expression was not significantly different from control rats. In females, the cannabinoid treatment increased the expression of CB1 receptor in non-maternally deprived animals; MD, per se, induced the opposite effect and animals receiving both treatments showed values that were similar to those corresponding to the pure controls, that is, control vehicle animals. In the SR–SP of CA1 area, the three-way ANOVA revealed the following significant interactions: sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 10.19, P<0.05], sex×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 5.45, P<0.05] and MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 5.15, P<0.05]. Subsequent two-way ANOVA split by sex revealed a significant MD×pharmacological treatment interaction [F(1,20) =12.49, P<0.05] in males and a significant effect of the pharmacological treatment [F(1,20) =4.88, P<0.05] in females. Post hoc comparisons showed that CP induced a significant decrease in CB1 receptor density, whereas this effect appeared to be reversed in males receiving both treatments. In SL–SM of CA1 area, the three-way ANOVA revealed the following significant interactions: sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) =30.21, P<0.05], sex×MD [F(1,40) =15.88, P<0.05] and MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 15.13, P<0.05] as well as a significant effect of MD [F(1,40) = 10.88, P<0.05]. Two-way ANOVA split by sex rendered a significant MD×pharmacological treatment interaction [F(1,20) = 38.20, P<0.05] in males, and a significant effect of MD [F(1,20) = 31.33, P<0.05] in females. Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in males, both MD and the cannabinoid treatment when considered separately, significant decreased CB1 immunoreactivity, whereas animals receiving both treatments were not different from controls. On the other hand, females receiving both treatments showed a significant reduction of CB1 immunoreactivity.

In CA3, we separately studied SO and the SR–SP. In both cases, the three-way ANOVA rendered similar results, revealing significant effects of the triple interaction sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [SO, F(1,40) = 5.48, P<0.05; SR–SP, F(1,40) = 7.44, P<0.05], the double interaction sex×MD [SO, F(1,40) = 14.46, P<0.05; SR–SP, F(1,40) = 6.13, P<0.05] and of sex [SO, F(1,40) = 7.92, P<0.05; SR–SP, F(1,40) =7.05, P<0.05]. Two-way ANOVA analysis split by sex rendered similar effects in both cases (SO and SR–SP). In males significant effects of the double interaction MD×pharmacological treatment was found [SO, F(1,20) = 7.70, P<0.05; SR–SP, F(1,20) = 12.10, P<0.05]. In females, in SO area the two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the pharmacological treatment [F(1,20) = 13.73, P<0.05] while in SR–SP it rendered a significant effect of MD [F(1,20) = 5.85, P<0.05]. In males, post hoc comparisons showed an increase in CB1 immunoreactivity in SO and SR–SP of CA3 in MDCP group when compared with MDVh. In females, a decrease of CB1 immunoreactivity in SO area was found in MDCP when compared with the CoCP group. The post hoc tests also revealed that, in both strata, MDVh and MDCP males showed higher levels of CB1 immunoreactivity than the corresponding female counterparts.

For the DG area, we carried out separate densitometrical analysis corresponding to (1) the molecular layer together with the granular cell layer (ml–gcl) and (2) the polymorphic cell layer. In both cases, the three-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of the triple interaction sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [ml–gcl, F(1,40) = 5.82, P<0.05; polymorphic layer, F(1,40) = 24.77, P<0.05]; the double interaction MD×pharmacological treatment [ml–gcl, F(1,40) = 6.55, P<0.05; polymorphic layer, F(1,40) = 21.69, P<0.05]. Besides, in ml–gcl, the three-way ANOVA also rendered a significant effect for the double interaction sex×MD [F(1,40) = 5.82, P<0.05], MD [F(1,40) = 5.07, P<0.05] and pharmacological treatment [F(1,40) = 4.51, P<0.05]. Subsequent two-way ANOVA within males showed that the interaction MD×pharmacological treatment was significant in both, ml–gcl [F(1,20) = 11.74, P<0.05] and polymorphic layer [F(1,20) = 50.97, P<0.05]. The corresponding two-way ANOVA in females revealed significant effects of MD [(F(1,20) = 11.48, P<0.05] and pharmacological treatment [F(1,20) = 5.87, P<0.05] in ml–gcl, whereas in polymorphic layer only a trend for MD was found (P = 0.085). Post hoc comparisons revealed a sexual dimorphism among control groups, with females showing lower levels of CB1 immunoreactivity in the polymorphic layer than their male counterpart. Separately, both MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure decreased CB1 immunoreactivity in the polymorphic layer in males, whereas males receiving both treatments showed a “normalized” CB1 receptor density. In Co-CP females a slight increase in CB1 receptor expression was found, whereas MD tended to decrease CB1 expression in both areas of the DG. Again, the combination of both treatments tended to normalize CB1 staining. In short, the above analyses reveal the following main results. In general, control females exhibited lower basal levels of CB1 receptor when compared with control males. In males, adolescent CP treatment induced a decrease in CB1 receptor density, whereas in females the opposite effect was found. The MD procedure induced a decrease in CB1 immunoreactivity in both sexes. Treatment with the cannabinoid agonist reversed the effects induce by MD in males, but not in females.

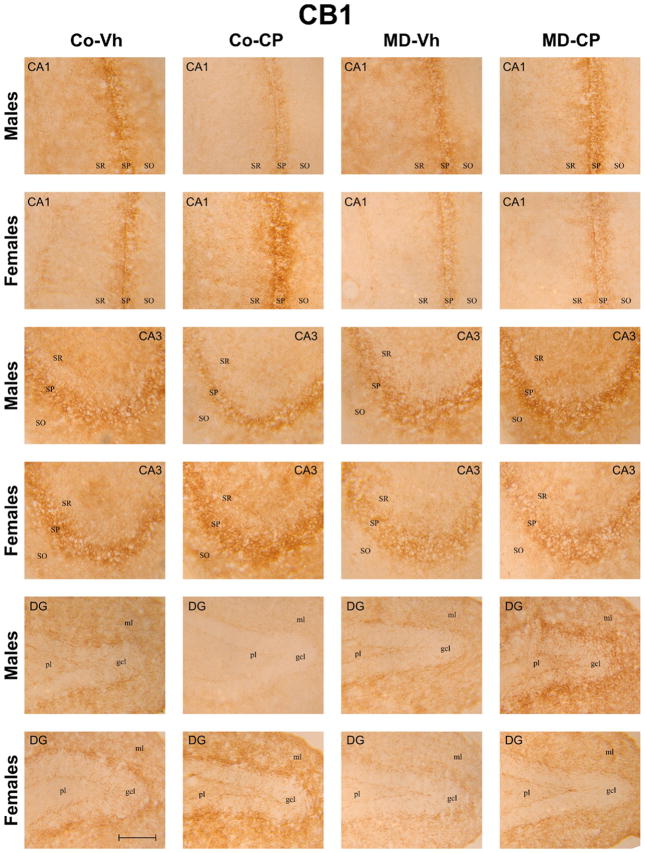

Fig. 4 shows representative microphotographs of CB1 immunoreactivity from CA1, CA3 and DG of all the experimental groups. CB1 immunoreactivity in the CA1 and CA3 areas was associated with fibers in the stratum radiatum and in the stratum pyramidale. A fine meshwork of stained fibers was evident in the stratum oriens of CA1 and CA3. The CB1 immunoreactivity was associated in DG with a network of fibers in the granular cell layer, molecular layer and in the polymorphic layer. We observed that the staining was more intense in CA3 than in CA1 and DG.

Fig. 4.

Representative microphotographs of CB1 immunoreactivity after maternal deprivation (MD) and adolescent treatment with the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 (CP) in CA1, and CA3 of Ammon’s Horn and in the Dentate Gyrus (DG) of the hippocampal formation of adult male and female rats. Scale bar 5 μm. MD, maternal deprivation; Co, control non MD animals; Vh, vehicle (see text); CP, CP 55,940; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum; gcl, granular cell layer; ml, molecular layer; pl, polymorphic layer. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.

BDNF

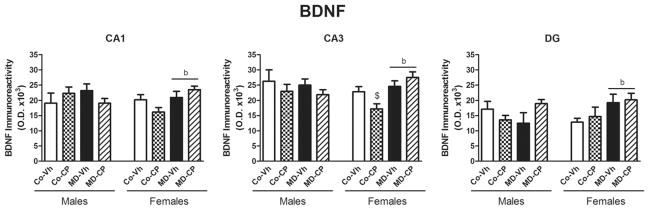

The changes in the intensity of BDNF immunohistochemistry staining were mainly observed in the stratum radiatum of CA1 and CA3 areas and in the polymorphic layer of the DG (microphotographs not shown), for that reason we analyzed the neuropil of these strata by a densitometric study. Results corresponding to the quantification of BDNF immunoreactivity are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of maternal deprivation (MD) and/or adolescent exposure to the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 on hippocampal BDNF expression of adult male and female rats. Quantification of BDNF immunoreactivity was carried out in CA1, and CA3 areas of Ammon’s Horn and in the Dentate Gyrus (DG). Histograms represent the mean±SEM of six animals per experimental group. MD, maternal deprivation; Co, control non MD animals; Vh, vehicle (see text); CP, CP 55,940. ANOVA (P<0.05); b, significant overall effect of maternal deprivation. Significant differences, P<0.05: $ vs. CoVh female.

In CA1 the three-way ANOVA rendered a significant effect of the triple interaction sex×MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,46) = 6.14, P<0.05]. Two-way ANOVA within females revealed a significant increase in BDNF expression in maternally deprived animals when compared with control groups [F(1,22) = 6.14, P<0.05], while in males no significant effects were found.

In CA3 the three-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the double interaction sex×MD [F(1,46) = 5.58, P<0.05]. Subsequent two-way ANOVA split by sex rendered significant effects of the double interaction MD×pharmacological treatment [F(1,22) = 5.68, P<0.05] and MD [F(1,22) = 11.34, P<0.05] in females, whereas no significant effects were found in males.

In DG the three-way ANOVA revealed strong trends for MD (P = 0.060) and for the double interaction sex×MD (P = 0.097). In order to further elucidate possible significant effects we performed additional two-way ANOVA. The two-way ANOVA split by sex revealed a significant effect of the double interaction MD×pharmacological treatment; [F(1,18) = 5.00, P<0.05] in males and a significant effect of MD [F(1,19) = 6.21, P<0.05] in females. The two-way ANOVA split by pharmacological treatment revealed a significant effect of the double interaction sex×MD [F(1,18) = 4.59, P<0.05] in the vehicle injected animals, and a significant effect MD [F(1,19) = 6.98, P<0.05] in the CP treated animals.

The main results regarding BDNF measurement can be summarized as follows. Control females exhibited lower basal levels of BDNF when compared with control males in CA3 and in DG. As Fig. 5 shows, the clearest differences were found in females. In this sex, adolescent cannabinoid exposure induced a decrease of BDNF expression in CA1 and CA3 areas that appeared to be compensated by MD, whereas the combination of both treatments appeared to result in an increase in BDNF in DG.

DISCUSSION

The present results show that both, MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure induced long-term sex-dependent effects on hippocampal GFAP, CB1 receptors and BDNF levels. In glial cells in the polymorphic cell layer of the DG adult control females exhibited higher basal levels of GFAP+ cells than males. Previously we found that PND 13 control females showed more hippocampal GFAP+ cells than control males. Moreover, we also found that control females showed more hippocampal Fluoro Jade-C (FJ-C)+ cells (i.e., degenerating neurons) than control males (Llorente et al., 2009). These data suggest that, at PND 13, the rates of “natural” apoptosis and astrocyte proliferation may be greater in females than in males. Potentially, these developmental differences might be involved in the generation of the sexual dimorphisms observed here in the adult animals. MD induced, in males, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in CA1 and CA3 areas and in the polymorphic layer of the DG. In a previous study this same MD procedure (24 h MD at PND 9) induced at PND 13 a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ and Fj-C+ cells in the hippocampus (Llorente et al., 2009). The present data demonstrate that the effect of MD is long lasting. The treatment with CP also induced, in control non-MD males, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in the polymorphic layer of the DG.

The differences in the number of GFAP+ immunoreactive cells induced by the present treatments may reflect developmental effects on the differentiation and proliferation of astrocytes or the activation of formerly quiescent astrocytes. An increased expression of GFAP and an increase in the number of GFAP+ immunoreactive astrocytes are markers of reactive gliosis that is associated to neurodegenerative modifications (Eng and Ghirnikar, 1994). One of the possible molecular changes in reactive astrocytes described by Sofroniew (2009) is an upregulation of GFAP expression. This could make it possible to detect astrocytes that would otherwise remain under the level of detection by immunohistochemistry in control rats. Therefore, part of the differences detected in the number of GFAP+ immunoreactive cells may reflect modifications in astrocyte reactivity, rather than number in response to neuronal cell death.

Human studies indicate that young cannabis users are more likely to use psychostimulants, hallucinogens or opioids than those who have never used cannabis (Fergusson et al., 2006), and experimental models have revealed that cannabinoids might induce lasting neuronal alterations that could affect the stimulant and/or reinforcing values of other drugs of abuse (Pistis et al., 2004; Ellgren et al., 2007). Interestingly, astrocytes have been implicated in the development of the rewarding effects and the drug dependence (Narita et al., 2008). It is tempting to speculate that the changes in GFAP+ hippocampal cells found in the present study might be related to this phenomenon. In relation to these relationships, endocannabinoids have been shown to activate reward-related feeding and to promote astrocytic differentiation (Higuchi et al., 2010).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE) proteomic analysis conducted on Δ9-THC-treated hippocampal samples revealed several proteins showing long-lasting alterations in response to THC administration. The greater number of differentially expressed protein spots in adolescent Δ9-THC pretreated rats compared with adult Δ9-THC-pretreated rats suggests a greater vulnerability to lasting effects of Δ9-THC in the former group. Differentially expressed proteins in adolescent Δ9-THC exposed rats included cytoskeletal and other structural proteins, including transgelin-3 (NP25), α- and β-tubulin and myelin basic protein (MBP) (Quinn et al., 2008). This may be linked to structural changes or remodeling occurring after Δ9-THC exposure in adolescents and is consistent with observations of cytoarchitectural changes occurring with cannabinoid treatment (Tagliaferro et al., 2006) and other reports of altered expression of the structural-related proteins tubulin and actin (Tahir et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 1996). As a whole, differentially expressed proteins in the hippocampus of Δ9-THC preexposed adolescents have a variety of functions broadly related to oxidative stress, mitochondrial and metabolic function and regulation of the cytoskeleton and signaling. The present data show that adolescent CP exposure tended to reduce BDNF expression in CA1 and CA3 of females, which is in line with the above results. In fact, BDNF exerts potent effects on neuronal function and survival and is important in maintaining dendritic morphology and synaptic function (Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). In turn, maternal deprivation counteracted the influence of CP and increased BDNF in females. Previous data about the effects at adulthood of maternal deprivation/ separation procedures on hippocampal BDNF functioning are conflicting. Although most of the studies have described a decrease in BDNF mRNA or protein levels (Roceri et al., 2002; Lippmann et al., 2007; Aisa et al., 2009; de Lima et al., 2011), in other cases no changes have been detected (Roceri et al., 2004; Choy et al., 2008; Réus et al., 2011) and even an increase in BDNF protein levels without changes in BDNF mRNA have been described (Greisen et al., 2005). We have previously found (Valero et al., 2011) that, at adolescence, MD, per se, decreased BDNF in the hippocampus. However, in this case the measurement was performed at adulthood and the animals received chronic injections, which may have contributed to counteract the effect of MD. It is also likely that the increase in BDNF in the adulthood is a compensatory effect.

As a whole, the results suggest that male hippocampal astrocytes were more vulnerable than females to the effects of MD and juvenile cannabinoid treatment on hippocampal astrocytes. This finding suggests the existence of protective mechanisms in females. Previous studies in adult rats have identified sexual dimorphisms relating to the effects of stress on the hippocampus and amygdala, with males being more vulnerable. These differences may depend on the protective effects of circulating gonadal hormones in females and/or on organizational developmental effects of gonadal steroids (Cooke et al., 1998; McEwen, 2007). Interestingly, sexual dimorphisms have been reported for the neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion model of schizophrenia with adult male rats showing more pronounced deficits in social behavior, grooming and water-maze learning than females (Silva-Gómez et al., 2003). Thus, female developmental neuroprotective mechanisms may have their functional correlate at the behavioral level in the long-term. We cannot rule out that the present sex differences are indicative of a different timing in the cellular effects of MD and CP in both sexes. Moreover, our results indicate a different vulnerability of different subregions within the hippocampus to both types of manipulations. The results obtained in the animals receiving the two treatments, that is, MD and the adolescent chronic cannabinoid agonist indicate functional interactions between the two types of manipulations. For instance, in CA3 areas and in the polymorphic layer of the DG, treatment with CP tended to counteract the effect of MD. Intriguingly, both treatments, when administered separately induced changes that go in the same direction whereas the combination of both manipulations appeared to lead to “normalization”.

A relevant finding of the present study is the occurrence of sex differences in CB1 receptor immunoreactivity among the control (vehicle-injected, non MD) animals, with control females showing lower CB1 receptor immunoreactivity in diverse areas of the hippocampal formation. Previous studies using Western blot analysis also indicated a sex difference in hippocampal CB1 levels with males having higher CB1 levels than females (Reich et al., 2009). MD induced a decrease in CB1 expression in adult males and females. We have previously shown that this same MD procedure (24 h MD at PND 9) induced a short-term (PND 13) reduction in hippocampal CB1 receptors in males but not females. The present data demonstrate that the effect of MD in males is long lasting. Moreover, whereas females where not affected by MD in infancy (PND 13) (Llorente et al., 2009; Viveros et al., 2009), adult MD female animals do show a decrease in their hippocampal CB1 expression. This fact might be attributable to a differential developmental profile of hippocampal CB1 cannabinoid receptors in male and female rats, suggesting that an accurate interpretation of sexual dimorphisms, at least for certain parameters requires a broad and dynamic perspective rather than a single observation at one age. In turn, adolescent cannabinoid exposure induced, in non deprived males, a general decrease in CB1 immunoreactivity in adulthood that was most marked in CA1 and in the polymorphic layer of the DG. This long-lasting decrease in CB1 receptor immunoreactivity in CP males may represent a mechanism of adaptation, which was not present in females. These data appear to be in agreement with our previous behavioural results obtained with the same animals used in this study (Llorente-Berzal et al., 2011). In this earlier report we found that females were in general more affected at adulthood by the adolescent cannabinoid treatment (reduction of the pre-pulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response reflex and increase in novelty-seeking/exploration measures in the holeboard). Interestingly, male animals receiving MD and adolescent CP exhibited a “normalization” of hippocampal CB1 expression. In line with the results obtained with GFAP, these data point to the existence of functional interactions between neonatal MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure. In contrast to the effect observed in males, nondeprived CP treated females tended to show an increase of hippocampal CB1 immunoreactivity. Relevant to this latter result, it has been very recently shown that chronic adolescent Δ9-THC interacted with ovarian hormones to produce persistent behavioral disruptions in female rats responding under an operant task comprised of both, learning and performance components as well as persistent alterations in CB1 receptor levels (Western blot). A primary example of these interactive effects occurred in the hippocampus where CB1 receptor density was significantly increased by Δ9-THC administration during adolescence (a result that coincides with our present data) but not if Δ9-THC administration was preceded by ovariectomy (Winsauer et al., 2010), indicating that the effect of adolescent THC on hippocampal CB1 receptors required ovarian hormones.

A large number of sex differences have been revealed in this study that deserves a final comment. In the original organizational–activational hypothesis of brain sexual differentiation, exposure to steroid hormones early in development masculinizes and defeminizes neural circuits (structural changes), programming behavioral responses to hormones in adulthood. Upon gonadal maturation during puberty, testicular and ovarian hormones act on previously sexually differentiated circuits to facilitate expression of sex-typical behaviours (activational effects) (Handa et al., 2008; Schwarz and McCarthy, 2008). Recently, it has been proposed that the remodeling adolescent brain is organized a second time by gonadal steroid hormones secreted during puberty. This second wave of brain organization would build on and refine circuits that were sexually differentiated during early neural development. If, in fact, steroid-dependent organization of behaviour occurs during adolescence, this prompts a reassessment of the developmental time-frame within which organizational effects are possible (Schulz et al., 2009). Regarding the present study, adolescent cannabis may have interfered with the reorganization mediated by the second wave.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, in males MD induced a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in CA1 and CA3 areas and in the polymorphic layer of the DG. In these latter two regions CP treatment tended to counteract the effect of MD. The treatment with CP induced, in control non-deprived males, a significant increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in the polymorphic layer of the DG. As a whole, these results suggest that males were more vulnerable than females to the effects of MD and juvenile cannabinoid treatment on hippocampal astrocytes. As for CB1 cannabinoid receptors, MD induced a decrease in CB1 expression in both, males and females. Adolescent cannabinoid exposure induced in non deprived males a general decrease in CB1 immunoreactivity that was most marked in CA1 and in the polymorphic layer of the DG. In contrast, nondeprived CP treated females tended to have increased hippocampal CB1 immunoreactivity. Male animals receiving the two treatments showed a certain “normalization” of hippocampal CB1 expression, indicating functional interactions between neonatal MD and adolescent cannabinoid exposure. As for BDNF this interaction was also observed since the trend of CP treatment to decrease BDNF was counteracted by MD. The data support the idea that astrocytes and CB1 receptors are crucial targets for long-lasting effects of both early-life stress and adolescent cannabis use, and encourage further research on the pathophysiological significance of these phenomena. Endocannabinoids promote astroglial differentiation through the activation of CB1 receptors (Aguado et al., 2006) and mediate neuron–astrocyte communication (Navarrete and Araque, 2008). The present results further highlight the potential functional importance of astrocytes and its interaction with the endocannabinoid system in relation to long-term consequences of adolescent cannabis exposure and highlight the urgent need of a deeper investigation of the functional significance of long-term changes in hippocampal CB1 receptors and astrocytes after adolescence cannabinoids exposure.

Acknowledgments

This research has been sponsored by grants to M.P.V.: Plan Nacional sobre Drogas Orden SAS/1250/2009, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Redes temáticas de Investigación Cooperativa en salud (ISCIII y FEDER): Red de trastornos adictivos (RD06/0001/1013), and GRUPOS UCM-BSCH (GRUPO UCM 951579), and by grants to A.A. and R.N.: Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2008-01175), Red de trastornos adictivos (RD06/0001/0015), and Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR2009-16) as well as to K.M.: the NIH (DA011322 and DA021696).

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- Co

control non deprived animals

- CP

CP-55,940

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DG

dentate gyrus

- ECS

endocannabinoid system

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HPA

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- IB

immunohistochemistry buffer

- MD

maternal deprivation

- ml–gcl

molecular layer together with the granular cell layer

- PND

postnatal day

- SL–M

stratum lacunosum together with moleculare

- SO

stratum oriens

- SR–SP

stratum pyramidale together with radiatum

- Vh

vehicle

- 2-AG

2-arachidonylglycerol

References

- Adriani W, Laviola G. Windows of vulnerability to psychopathology and therapeutic strategy in the adolescent rodent model. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:341–352. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado T, Palazuelos J, Monory K, Stella N, Cravatt B, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Kokaia Z, Guzmán M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid system promotes astroglial differentiation by acting on neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1551–1561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3101-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisa B, Elizalde N, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Río J, Ramírez MJ. Effects of neonatal stress on markers of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus: implications for spatial memory. Hippocampus. 2009;19:1222–1231. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Silva FJ, Viveros MP, McPartland JM, Rodriguez de Fonseca F. The endocannabinoid system, eating behavior and energy homeostasis: the end or a new beginning? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscaia M, Fernández B, Higuera-Matas A, Miguéns M, Viveros MP, García-Lecumberri C, Ambrosio E. Sex-dependent effects of periadolescent exposure to the cannabinoid agonist CP-55,940 on morphine self-administration behaviour and the endogenous opioid system. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscaia M, Marin S, Fernandez B, Marco EM, Rubio M, Guaza C, Ambrosio E, Viveros MP. Chronic treatment with CP 55,940 during the peri-adolescent period differentially affects the behavioural responses of male and female rats in adulthood. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy KH, de Visser Y, Nichols NR, van den Buuse M. Combined neonatal stress and young-adult glucocorticoid stimulation in rats reduce BDNF expression in hippocampus: effects on learning and memory. Hippocampus. 2008;18:655–667. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B, Hegstrom CD, Villeneuve LS, Breedlove SM. Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate brain: principles and mechanisms. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1998;19:323–362. doi: 10.1006/frne.1998.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D. The role of the endocannabinoid system in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima MN, Presti-Torres J, Vedana G, Alcalde LA, Stertz L, Fries GR, Roesler R, Andersen ML, Quevedo J, Kapczinski F, Schröder N. Early life stress decreases hippocampal BDNF content and exacerbates recognition memory deficits induced by repeated D-amphetamine exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2011;224:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Forti M, Morrison PD, Butt A, Murray RM. Cannabis use and psychiatric and cogitive disorders: the chicken or the egg? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:228–234. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280fa838e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertová M, Elphick MR. Localisation of cannabinoid receptors in the rat brain using antibodies to the intracellular C-terminal tail of CB. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:159–171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000626)422:2<159::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbroek BA, de Bruin NM, van Den Kroonenburg PT, van Luijtelaar EL, Cools AR. The effects of early maternal deprivation on auditory information processing in adult Wistar rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbroek BA, Riva MA. Early maternal deprivation as an animal model for schizophrenia. Clin Neurosci Res. 2003;3:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ellgren M, Spano SM, Hurd YL. Adolescent cannabis exposure alters opiate intake and opioid limbic neuronal populations in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:607–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng LF, Ghirnikar RS. GFAP and astrogliosis. Brain Pathol. 1994;4:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101:556–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Espejo E, Viveros MP, Nunez L, Ellenbroek BA, Rodriguez de Fonseca F. Role of cannabis and endocannabinoids in the genesis of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:531–549. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greisen MH, Altar CA, Bolwig TG, Whitehead R, Wörtwein G. Increased adult hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor and normal levels of neurogenesis in maternal separation rats. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:772–778. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Pak TR, Kudwa AE, Lund TD, Hinds L. An alternate pathway for androgen regulation of brain function: activation of estrogen receptor beta by the metabolite of dihydrotestosterone, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol. Horm Behav. 2008;53:741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton WJ, von Bartheld CS. Analysis of cell death in the trochlear nucleus of the chick embryo: calibration of the optical disector counting method reveals systematic bias. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:169–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Irie K, Mishima S, Araki M, Ohji M, Shirakawa A, Akitake Y, Matsuyama K, Mishima K, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M. The cannabinoid 1-receptor silent antagonist O-2050 attenuates preference for high-fat diet and activated astrocytes in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:369–372. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09326sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Matas A, Botreau F, Miguéns M, Del Olmo N, Borcel E, Pérez-Alvarez L, García-Lecumberri C, Ambrosio E. Chronic periadolescent cannabinoid treatment enhances adult hippocampal PSA-NCAM expression in male Wistar rats but only has marginal effects on anxiety, learning and memory. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Matas A, Soto-Montenegro ML, del Olmo N, Miguéns M, Torres I, Vaquero JJ, Sánchez J, García-Lecumberri C, Desco M, Ambrosio E. Augmented acquisition of cocaine self-administration and altered brain glucose metabolism in adult female but not male rats exposed to a cannabinoid agonist during adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:806–813. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keimpema E, Mackie K, Harkany T. Molecular model of cannabis sensitivity in developing neuronal circuits. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Marco EM. Passing the knife edge in adolescence: brain pruning and specification of individual lines of development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1631–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawston J, Borella A, Robinson JK, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Changes in hippocampal morphology following chronic treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2. Brain Res. 2000;877:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Developmental determinants of sensitivity and resistance to stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leweke FM, Koethe D. Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction. Addict Biol. 2008;13:264–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Dimen KR, Martin BR. Systemic or intrahippocampal cannabinoid administration impairs spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:282–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02246292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Bress A, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM, Monteggia LM. Long-term behavioural and molecular alterations associated with maternal separation in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3091–3098. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente R, Arranz L, Marco EM, Moreno E, Puerto M, Guaza C, De la Fuente M, Viveros MP. Early maternal deprivation and neonatal single administration with a cannabinoid agonist induce long-term sex-dependent psychoimmunoendocrine effects in adolescent rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:636–650. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente R, Gallardo ML, Berzal AL, Prada C, Garcia-Segura LM, Viveros MP. Early maternal deprivation in rats induces gender-dependent effects on developing hippocampal and cerebellar cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2009;27:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente R, Llorente-Berzal A, Petrosino S, Marco EM, Guaza C, Prada C, López-Gallardo M, Di Marzo V, Viveros MP. Gender-dependent cellular and biochemical effects of maternal deprivation on the hippocampus of neonatal rats: a possible role for the endocannabinoid system. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:1334–1347. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente-Berzal A, Fuentes S, Gagliano H, Lopez-Gallardo M, Armario A, Viveros MP, Nadal R. Sex-dependent effects of maternal deprivation and adolescent cannabinoid treatment on adult rat behaviour. Addict Biol. 2011;16:624–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Gallardo M, Llorente R, Llorente-Berzal A, Marco EM, Prada C, Di Marzo V, Viveros MP. Neuronal and glial alterations in the cerebellar cortex of maternally deprived rats: gender differences and modulatory effects of two inhibitors of endocannabinoid inactivation. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:1429–1440. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. In: Pertwee RG, editor. Cannabinoids handbook of experimental pharmacology. Vol. 168. Berlin: Springer; 2005. pp. 299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrì S, Laviola G. Single episode of maternal deprivation and adult depressive profile in mice: interaction with cannabinoid exposure during adolescence. Behav Brain Res. 2004;154:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Adriani W, Canese R, Podo F, Viveros MP, Laviola G. Enhancement of endocannabinoid signalling during adolescence: modulation of impulsivity and long-term consequences on metabolic brain parameters in early maternally deprived rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos B, Borcel E, Loriga R, Luesu W, Bini V, Llorente R, Castelli M, Viveros MP. Adolescent exposure to nicotine and/or the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 induces gender-dependent long-lasting memory impairments and changes in brain nicotinic and CB1 cannabinoid receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0269881110370503. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett MC, Vicentic A, Kozel M, Plotsky P, Francis DD, Kuhar MJ. Maternal separation alters drug intake patterns in adulthood in rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system: emotion, learning and addiction. Addict Biol. 2008;13:196–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Suzuki M, Kuzumaki N, Miyatake M, Suzuki T. Implication of activated astrocytes in the development of drug dependence: differences between methamphetamine and morphine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:96–104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete M, Araque A. Endocannabinoids mediate neuron-astrocyte communication. Neuron. 2008;57:883–893. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. London, UK: Elsevier; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistis M, Perra S, Pillolla G, Melis M, Muntoni AL, Gessa GL. Adolescent exposure to cannabinoids induces long-lasting changes in the response to drugs of abuse of rat midbrain dopamine neurons. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn HR, Matsumoto I, Callaghan PD, Long LE, Arnold JC, Gunasekaran N, Thompson MR, Dawson B, Mallet PE, Kashem MA, Matsuda-Matsumoto H, Iwazaki T, McGregor IS. Adolescent rats find repeated Delta(9)-THC less aversive than adult rats but display greater residual cognitive deficits and changes in hippocampal protein expression following exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1113–1126. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MG, Howard CV. Surface-weighted star volume: concept and estimation. J Microsc. 1998;190:350–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich CG, Taylor ME, McCarthy MM. Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on hippocampal CB1 receptors in male and female rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;203:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Réus GZ, Stringari RB, Ribeiro KF, Cipriano AL, Panizzutti BS, Stertz L, Lersch C, Kapczinski F, Quevedo J. Maternal deprivation induces depressive-like behaviour and alters neurotrophin levels in the rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:460–466. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbe D, Montgomery SM, Thome A, Rueda-Orozco PE, Mc-Naughton BL, Buzsaki G. Cannabinoids reveal importance of spike timing coordination in hippocampal function. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roceri M, Cirulli F, Pessina C, Peretto P, Racagni G, Riva MA. Postnatal repeated maternal deprivation produces age-dependent changes of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in selected rat brain regions. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roceri M, Hendriks W, Racagni G, Ellenbroek BA, Riva MA. Early maternal deprivation reduces the expression of BDNF and NMDA receptor subunits in rat hippocampus. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:609–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Ramos JA, Bonnin A, Fernández-Ruiz JJ. Presence of cannabinoid binding sites in the brain from early postnatal ages. Neuroreport. 1993;4:135–138. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD. Puberty: a period of both organizational and activational effects of steroid hormones on neurobehavioural development. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:1185–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2003.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Vigano D, Realini N, Guidali C, Braida D, Capurro V, Castiglioni C, Cherubino F, Romualdi P, Candeletti S, Sala M, Parolaro D. Chronic delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence provokes sex-dependent changes in the emotional profile in adult rats: behavioral and biochemical correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2760–2771. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Puberty as a highly vulnerable developmental period for the consequences of cannabis exposure. Addict Biol. 2008;13:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KM, Molenda-Figueira HA, Sisk CL. Back to the future: the organizational-activational hypothesis adapted to puberty and adolescence. Horm Behav. 2009;55:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, McCarthy MM. Steroid-induced sexual differentiation of the developing brain: multiple pathways, one goal. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1561–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell RA, Ranganathan M, D’Souza DC. Cannabinoids and psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:152–162. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Gómez AB, Bermudez M, Quirion R, Srivastava LK, Picazo O, Flores G. Comparative behavioral changes between male and female postpubertal rats following neonatal excitotoxic lesions of the ventral hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003;973:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez J, Llorente R, Romero-Zerbo SY, Mateos B, Bermúdez-Silva FJ, de Fonseca FR, Viveros MP. Early maternal deprivation induces gender-dependent changes on the expression of hippocampal CB(1) and CB(2) cannabinoid receptors of neonatal rats. Hippocampus. 2009;19:623–632. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez J, Rivera P, Llorente R, Romero-Zerbo SY, Bermúdez-Silva FJ, de Fonseca FR, Viveros MP. Early maternal deprivation induces changes on the expression of 2-AG biosynthesis and degradation enzymes in neonatal rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2010;1349:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundram S. Cannabis and neurodevelopment: implications for psychiatric disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:245–254. doi: 10.1002/hup.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferro P, Javier Ramos A, Onaivi ES, Evrard SG, Lujilde J, Brusco A. Neuronal cytoskeleton and synaptic densities are altered after a chronic treatment with the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2. Brain Res. 2006;1085:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferro P, Ramos AJ, López EM, Pecci Saavedra J, Brusco A. Neural and astroglial effects of a chronic parachlorophenylalanine-induced serotonin synthesis inhibition. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1997;32:195–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02815176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir SK, Trogadis JE, Stevens JK, Zimmerman AM. Cytoskeletal organization following cannabinoid treatment in undifferentiated and differentiated PC12 cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 1992;70:1159–1173. doi: 10.1139/o92-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier L, Price LH, Ross N, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Carpenter LL. Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero M, Marco EM, De La Serna O, Borcel E, Llorente R, Ramirez MJ, Viveros MP. Detrimental cognitive effects of early maternal deprivation in adolescent male and female rats. Putative underlying mechanisms; 8th IBRO World Congress of Neuroscience Florence.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Llorente R, López-Gallardo M, Suarez J, Bermúdez-Silva F, De la Fuente M, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Garcia-Segura LM. Sex-dependent alterations in response to maternal deprivation in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34 (Suppl 1):S217–S226. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Llorente R, Suarez J, Llorente-Berzal A, Lopez-Gallardo M, Rodriguez de Fonseca F. The endocannabinoid system in critical neurodevelopmental periods: sex differences and neuropsychiatric implications. J Psychopharmacol. 2011b doi: 10.1177/0269881111408956. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, File SE. Endocannabinoid system and stress and anxiety responses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, Llorente R, Lopez-Gallardo M. Endo-cannabinoid system and synaptic plasticity: implications for emotional responses. Neural Plast. 2007;2007:52908. doi: 10.1155/2007/52908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, Lopez-Gallardo M, Garcia-Segura LM, Wagner EJ. Framework for sex differences in adolescent neurobiology: a focus on cannabinoids. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011a;35:1740–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener N, Koch M. Behavioural disturbances and altered Fos protein expression in adult rats after chronic pubertal cannabinoid treatment. Brain Res. 2009;1253:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RG, Jr, Tahir SK, Mechoulam R, Zimmerman S, Zimmerman AM. Cannabinoid enantiomer action on the cytoarchitecture. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20:147–157. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsauer PJ, Daniel JM, Filipeanu CM, Leonard ST, Hulst JL, Rodgers SP, Lassen-Greene CL, Sutton JL. Long-term behavioral and pharmacodynamic effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in female rats depend on ovarian hormone status. Addict Biol. 2010;16:64–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotjak CT. Role of endogenous cannabinoids in cognition and emotionality. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:659–670. doi: 10.2174/1389557054368763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]