Abstract

The myometrium must remain relatively quiescent during pregnancy to accommodate growth and development of the feto-placental unit, and then must transform into a highly coordinated, strongly contracting organ at the time of labour for successful expulsion of the new born. The control of timing of labour is complex involving interactions between mother, fetus and the placenta. The timely onset of labour and delivery is an important determinant of perinatal outcome. Both preterm birth (delivery before 37 week of gestation) and post term pregnancy (pregnancy continuing beyond 42 weeks) are both associated with a significant increase in perinatal morbidity and mortality. There are multiple paracrine/autocrine events, fetal hormonal changes and overlapping maternal/fetal control mechanisms for the triggering of parturition in women. Our current article reviews the mechanisms for uterine distension and reduced contractions during pregnancy and the parturition cascade responsible for the timely and spontaneous onset of labour at term. It also discusses the mechanisms of preterm labour and post term pregnancy and the clinical implications thereof.

Keywords: Endocrine, parturition, labour, term

INTRODUCTION

Labour is the physiologic process by which a fetus is expelled from the uterus. It requires the presence of regular painful uterine contractions, which increase in frequency, intensity and duration leading to progressive cervical effacement and dilatation. In normal labour, there appears to be a time-dependent relationship between these elements: The biochemical connective tissue changes in the cervix usually precede uterine contractions that, in turn, lead to cervical dilatation. All of these events culminate in spontaneous rupture of the fetal membranes.[1] The mean duration of human singleton pregnancy is 280 days (40 weeks) from the first day of the last normal menstrual period. “Term” is defined as the period from 37.0 to 42.0 weeks of gestation. Preterm birth (defined as delivery before 37 weeks' gestation) and post-term pregnancy (defined as pregnancy continuing beyond 42 weeks) is both associated with a significant increase in perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Studies in animals have underlined the importance of fetus in control of timing of labor. Activated fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis leads to a surge in adrenal cortisol production. Fetal cortisol stimulates activity of placental 17 α hydroxylase/17, 20 lyase (CYP 17) enzyme, which catalyzes the conversion of pregnenolone to estradiol.[1] The altered ratio of progesterone: estrogen in favor of later, up regulates the synthesis of uterine prostaglandins (PG) and labour.[2–7] Human placenta lacks CYP 17 and as such, the mechanism of labour is different.

Parturition in most animals results from changes in circulating hormone levels in the maternal and fetal circulations at the end of pregnancy (endocrine events), whereas labour in humans results from a complex dynamic biochemical dialog that exists between the fetoplacental unit and the mother (paracrine and autocrine events).

STEPS IN PARTURITION

In pregnancy there is a dynamic balance between the forces that cause uterine quiescence and the forces that produce coordinated uterine contractility. There is also a balance between the forces that keep the cervix closed to prevent uterine emptying and the forces that soften the cervix and allow it to dilate. For delivery to occur, both balances must be tipped in favor of active uterine emptying.[6,7] Many of the elements in this parturition complex elaborate feed forward characteristics. Labour at term is physiologically regarded as a release from the inhibitory effects of pregnancy on myometrium.[8] Human labour at term is a multifactorial physiologic event involving integrity of complementary endocrine, paracrine and autocrine factors leading to gradual changes within maternal uterine tissues (myometrium, deciduas and uterine cervix).

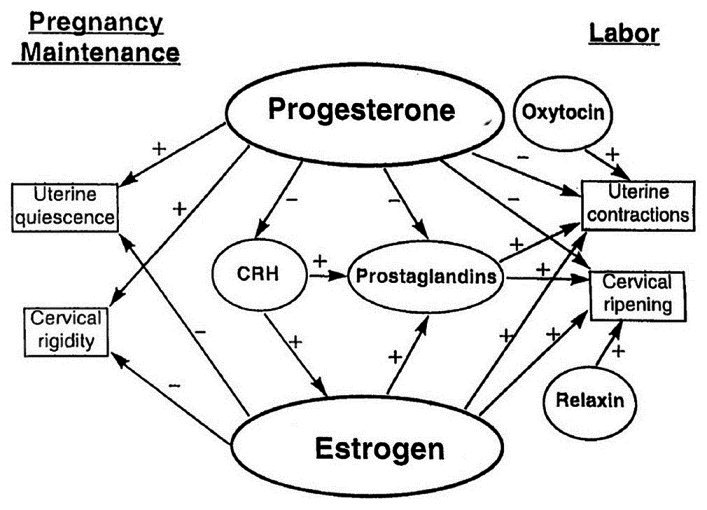

For parturition to occur, two changes must take place in a woman's reproductive tract. First, the uterus must be converted from a quiescent structure with dyssynchronous contractions to an active co-ordinately contracting organ with complex interlaced muscular components resulting in regular phasic uterine contractions. This requires the formation of gap junctions between myometrial cells to allow for transmission of the contractile signal. The fetus may coordinate this switch in myometrial activity through its influence on placental steroid hormone production, through the mechanical distention of the uterus and through the secretion of neurohypophyseal hormones and other stimulators of prostaglandin synthesis. The second change is that the cervical connective tissue and smooth muscle must be capable of dilatation to allow the passage of the fetus from the uterus. These changes are accompanied by shift from progesterone to estrogen dominance, increased responsiveness to oxytocin by means of up regulation of myometrial oxytocin receptor, increased PG synthesis in uterus, increased myometrial gap junction formation, decreased nitric oxide (NO) activity and increased influx of calcium into myocytes[9,10] with ATP dependent binding of myosin to actin,[11] increased endothelin leading to augmented uterine blood flow and myometrial activity[12] [Figure 1]. The final common pathway toward labour appears to be the activation of the fetal HPA axis and is probably common to all viviparous species. Complementary changes in the cervix involving a decrease in progesterone dominance and the actions of prostaglandins and relaxin, via connective tissue alterations, collagenolysis, and a decrease in collagen stabilization through metalloproteinase inhibitors, lead to cervical softening and dilation.[13]

Figure 1.

Endocrinological control of pregnancy and parturition in women. The balance between the effects of estrogen and progesterone is critical to maintenance of pregnancy and the onset of labor. Other important hormonal factors modulate this balance as shown in the scheme

EXCITABILITY IN UTERINE SMOOTH MUSCLES AND COORDINATION OF MYOMETRIAL CONTRACTILITY; ROLE OF HORMONES

Transformation of uterine myometrium from a state of quiescence to coordinated muscle contraction, involves changes in the density and activity of ion channels and pumps, and of gap junctions, which facilitate the spread of activity throughout the muscle cells in the uterine wall. These changes are achieved by local and circulating hormones in the lead up to labour, a process that has been termed ‘activation’.[14] The contractility of myometrium is heralded by origin of action potentials (AP) with subsequent spread among muscle fibres. The APs consist of both simple spikes and complex forms. Simple spikes in human myometrium are attributed to L-type calcium channels, transient sodium channels and rapidly activating and inactivating calcium channels.[15] Complex APs consist of simple spikes followed by a sustained plateau of depolarization. This form of AP is most conspicuous in inner layer and upper segment (fundus) of uterus and occurs throughout 3rd trimester and during labour.[16] Duration of plateau dictates the duration of contraction.[15,17,18] Rapid propagation of AP throughout the uterus is mediated by action potential calcium wave hypothesis.[19] Key elements of this hypothesis include the following

APs propagate through the uterus and initiate intercellular calcium waves. This step synchronizes the initiation of the contraction through the thickness of the wall and among all regions of the uterus.

Following initiation by an AP, an intercellular calcium wave propagates through each bundle and individual myocytes contract as the wave passes. Calcium waves do not cross boundaries between bundles. Either functional gap junctions or paracrine signalling mechanisms are required for intercellular calcium wave propagation.

Electrical activity is not required for the direct recruitment of myocytes for contraction; however, gap junction function is essential for the action potential to propagate through each bundle in the uterus. The proportion of myocytes that contract as a direct result of experiencing the initiating action potential could be very small (<1%).

Each myocyte remains contracted as long as the [Ca2+]i remains elevated, the duration of which is determined by the calcium metabolism of each individual cell.

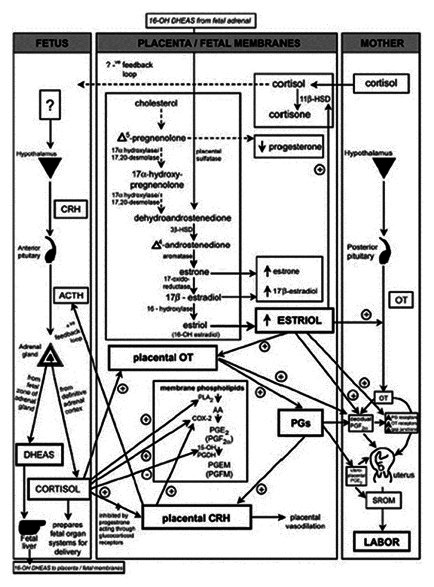

Prostaglandin F2α and oxytocin increase the opening of L-type calcium channels in response to depolarization. Estrogen is involved in the change in the form of AP to complex forms. Oxytocin enhances the plateau component of complex APs leading to gradual increase in duration of contractions as gestation ends[19] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Parturition cascade leading to labour induction at term. The induction of labour at term is reegulated by paracrine and autocrine factors acting in coordination promote uterine contraction. COX-2: Cyclooxygenase 2, OT: Oxytocin, PGDH: Prostaglandin dehydrogenase, PGEM: 13, 14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, PGFM: 13, 14-dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α, PLA2: Phospholipase A, SROM: Spontaneous rupture of the fetal membranes, 11β-HSD: 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 16-OH DHEAS: 16-hydroxy-dehydroepiandrostendione sulfate

MYOMETRIAL ACTIVATION DURING LABOUR

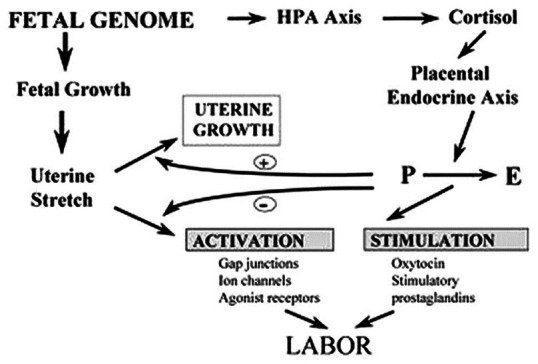

Trigger for onset of labour comprises a fetal endocrine cascade involving the fetal H-P-A axis which, in most species, leads to an increase in estrogen and decrease in progesterone in maternal plasma.[20] This endocrine cascade ultimately leads to both the ‘activation’ (contraction-associated protein (CAP) expression) and the ‘stimulation’ of the myometrium through the increased production of uterotonic agonists such as oxytocin and stimulatory prostaglandins [Figure 3]. Activation is associated with increased expression of the gap junction protein, connexin-43(Cx-43) as well as the oxytocin receptor (OTR) and prostaglandin F receptor. Expression of these CAPs is regulated positively by estrogen and negatively by progesterone, and CAP expression is increased in preterm labour but does not increase when labour is blocked by progesterone.[21] Expression of other CAPs such as the sodium channel and calcium channel is also increased close to term. Other putative CAPs are expressed in the uterus, including enzymes that regulate uterotonin levels (e.g., oxytocin endopeptidase and cyclooxygenase), proteins which interact with actin/myosin (e.g., MLCK, calmodulin), other uterotonin receptors (e.g., endothelin, thromboxane A2, α-adrenergic and potassium channels, however, there is no strong evidence to link their expression in the myometrium with the onset of term or preterm labor. Estrogen increases transcription of the Cx-43 and OTR genes. Estrogen also significantly increases the levels of mRNA encoding the AP-1 protein, c-fos in the myometrium that precedes the increased expression of Cx-43. The onset of term and preterm labour in the rat is associated with increased expression of c-fos and the fos family members fra-1 and fra-2, and Cx-43 and expression of these genes is attenuated when labour is blocked by progesterone. progesterone, a critical pregnancy-maintaining hormone, can block stretch-induced gene expression in the myometrium and maintain myometrial growth post-term.[22]

Figure 3.

Dual pathway by which the fetal genome controls the onset of labour through endocrine and mechanical signals. HPA-Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal, P-progesterone, E-estrogen

Now let us review the role of different hormones in parturition, in detail

CORTICOTROPIN RELEASING HORMONE

Corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) is a peptide hormone released by the hypothalamus but is also expressed by placental and chorionic trophoblasts and amnionic and decidual cells.[23–25] In fact from second trimester (16thweek onwards), the placenta is the major source of CRH secretion.[23] CRH stimulates pituitary ACTH secretion and adrenal cortisol production. In the mother, cortisol inhibits hypothalamic CRH and pituitary ACTH release, creating a negative feedback loop. In contrast, cortisol stimulates CRH release by the decidual, trophoblastic, and fetal membranes.[25–28] CRH, in turn, further drives maternal and fetal HPA activation, thereby establishing a potent positive feed-forward loop. In normal pregnancy, the increased production of CRH from decidual, trophoblastic, and fetal membranes leads to an increase in circulating cortisol beginning in midgestation.[29] The effects of CRH are enhanced by a fall in maternal plasma CRH-binding protein near term.[30] Activation of the fetal HPA axis results in enhanced fetal pituitary adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) secretion that leads, in turn, to the release of abundant C19 estrogen precursor dehydroepiandrostenedionesulfate (DHEAS) from the intermediate (fetal) zone of the fetal adrenal [Figure 2]. This is because the human placenta is an incomplete steroidogenic organ and estrogen synthesis by the human placenta has an obligate need for C19 steroid precursor [Figure 2].[31] DHEAS is converted in the fetal liver to 16-hydroxy DHEAS and then travels to the placenta where it is metabolized into estradiol (E2), estrone (E1), and estriol (E3). The action of estrogen is likely paracrine-autocrine.[32,33] In addition to DHEAS, the fetal adrenal glands also produce copious amounts of cortisol. Cortisol acts to prepares fetal organ systems (by fetal lung maturation) for extrauterine life and to promote expression of a number of placental genes, including corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), oxytocin, and prostaglandins (especially prostaglandin E2 [PGE2]). CRH also enhances prostaglandin production by amnionic, chorionic, and decidual cells.[25] Prostaglandins, in turn, stimulate CRH release from the decidual and fetal membranes.[26] The rise in prostaglandins ultimately results in parturition.[34] CRH also can directly affect myometrial contractility.[35] Other actions of CRH include dilation of the uterine vessels and stimulation of smooth muscle contractions, dilation of the fetal placental vessels via NO synthetase activation; and stimulation of prostaglandins F2α and E2 production by fetal membranes and decidua.[36–38] These are all actions conducive to the initiation of labour. CRH is also stimulated by inflammatory cytokines.[39]

ESTROGEN

Pregnancy is a hyperestrogenic state. The placenta is the primary source of estrogen and concentration of estrogen increases with progressing gestational age. The human placenta lacks CYP 17, needed for conversion from progesterone to estradiol. The fetal zone of the adrenal gland produces DHEAS, which may be hydroxylated to 16-OH-DHEAS in the fetal liver. The 16-OH-DHEAS may be aromatized by the placenta to produce estriol, the major circulating estrogen of human pregnancy [Figure 2]. In contrast to the nonpregnant state, during late human pregnancy the ovary is a minor source of circulating estrogens. Estradiol and estrone are synthesized primarily (90%) by aromatization of maternal C 19 androgens (testosterone and androstenedione), whereas estriol is derived exclusively from the fetal C19 estrogen precursor (DHEAS). Estriol concentrations in serum and saliva increase during the last four to six weeks of pregnancy.

Estrogens promote a series of myometrial changes including increased production of PG E2 and PG F2α with augmented expression of PG receptors,[40] increased receptor expression of oxytocin, α adrenergic agonist which modulate membrane calcium channels,[41] increased synthesis of connexin and gap junction formation in myometrium,[42] up regulation of enzyme responsible for muscle contraction like myosin light chain kinase, calmodulin.[43–46] All these changes allow coordinated uterine contractions.

Cervical ripening may be associated with the down-regulation of the estrogen receptor. The control of the softening of the cervix, which involves rearrangement and realignment of collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycans such as decorin, is not well studied and is poorly understood.[13]

PROGESTERONE

Corpus luteum is the source of progesterone till seven weeks of pregnancy. Placenta takes over the function at approximately seven to nine weeks of gestation. In pregnancy progesterone is in dynamic balance with estrogen in the control of uterine activity. Animals demonstrate systemic progesterone withdrawal as an essential component in initiation of labour. Humans though do not show fall in circulating progesterone, there is growing number of evidence that,[47–51] spontaneous onset of labour is preceded by a physiologic withdrawal of progesterone activity at the level of uterine receptors.

Progesterone in vitro decreases myometrial contractility and inhibits myometrial gap junction formation.[52] Progesterone activity stimulates the uterine NO synthetase, which is a major factor in uterine quiescence. Progesterone down-regulates prostaglandin production, as well as the development of calcium channels and oxytocin receptors both involved in myometrial contraction.[52] Calcium is necessary for the activation of smooth muscle contraction. In the cervix, progesterone increases tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1).[53] TIMP-1 inhibits collagenolysis. Thus, it is clear that progesterone is a major factor in uterine quiescence and cervical integrity. The factors that result in parturition must overcome the progesterone effect that predominates during the early pregnancy period of uterine quiescence. The activity of 17, 20 hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in fetal membranes increases around the time of parturition, leading to an increase in net 17β-estradiol and 20-dihydroprogesterone.[54] This is a factor in altering the estrogen/progesterone balance. There may be decreased progesterone receptor levels at term resulting in a diminished progesterone effect.

Cortisol and progesterone appear to have antagonistic actions within the fetoplacental unit. For example, cortisol increases prostaglandin production by the placental and fetal membranes by up-regulating cyclooxygenase-2 (amnion and chorion) and down-regulating 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-OH-PGDH) (chorionic trophoblast), thereby promoting cervical ripening and uterine contractions. Progesterone has the opposite effect.[55] In addition, cortisol has been shown to compete with the inhibitory action of progesterone in the regulation of placental CRH gene expression in primary cultures of human placenta.[56] It is likely, therefore, that the cortisol-dominant environment of the fetoplacental unit just before the onset of labour may act through a series of autocrine-paracrine pathways to overcome the efforts of progesterone to maintain uterine quiescence and prevent myometrial contractions.

PROSTAGLANDINS

Prostaglandins are formed from arachidonic acid that is converted to prostaglandin H2 by the enzyme prostaglandin H synthetase (PGHS). PGHS-2 is an inducible form of the enzyme. Cytokines increase the concentration of this enzyme 80-fold. Prostaglandins are degraded by 15-OH-PGDH. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) is cytokine inducible, is increased by NO. This is another mechanism by which prostaglandin production increases during inflammation.

There is good evidence that prostaglandins are involved in the final pathway of uterine contractility and parturition. Prostacyclins, inhibitory prostaglandins present throughout early pregnancy, are also responsible for uterine quiescence during pregnancy. Although prostaglandins may not be obligatory for labour in knockout mice, they are of major importance in women.[57,58] Prostaglandins are produced in the placenta and fetal membranes. Prostaglandin levels are increased before and during labour in the uterus and membranes.[59,60] PGF2α is produced primarily by the maternal decidua and acts on the myometrium to up-regulate oxytocin receptors and gap junctions, thereby promoting uterine contractions. PGE2 is primarily of fetoplacental origin and is likely more important in promoting cervical ripening (maturation) associated with collagen degradation and dilation of cervical small blood vessels[61] and spontaneous rupture of the fetal membranes [Figure 2]. Many factors affect the production of prostaglandins. Levels are decreased by progesterone and increased by estrogens.[62–65] Several interleukins result in an increase in prostaglandin production.[66]

OTHER FACTORS

Circulating oxytocin does not increase in labour until after full cervical dilatation.[67] Oxytocin is less effective in causing uterine contractions in mid pregnancy than at term. However, the concentration of uterine oxytocin receptors increases toward the end of pregnancy.[68] This results in increased efficiency of oxytocin action as pregnancy progresses. Estrogen increases oxytocin receptor expression and progesterone suppresses such estrogen-induced increase in cultured human myometrial cells.[69] Oxytocin induces uterine contractions in two ways. Oxytocin stimulates the release of PGE2 and prostaglandin F2α in fetal membranes by activation of phospholipase C. The prostaglandins stimulate uterine contractility.[70] Oxytocin can also directly induce myometrial contractions through phospholipase C (PLC), which in turn activates calcium channels and the release of calcium from intracellular stores.[71,72] Oxytocin is locally produced in the uterus.[73] The role of this local endogenous oxytocin is unknown.

Relaxin is a peptide hormone that is a member of the insulin family. Relaxin consists of A and B peptide chains linked together by two disulfide bonds. In women, circulating relaxin is a product of the corpus luteum of pregnancy. Circulating relaxin is secreted in a pattern similar to that of human chorionic gonadotropin. That circulating relaxin is not critical for pregnancy maintenance However; relaxin is also a product of the placenta and decidua. Relaxin from these sources, which may act locally, is not secreted into the peripheral circulation.[74] Relaxin receptors are present on the human cervix.[75] Some of the effects of relaxin include stimulation of procollagenase and prostromelysin, as well as a decrease in TIMP-1.[76] Relaxin is also capable of inhibiting contractions of non-pregnant human myometrial strips.[77] Paradoxically, relaxin does not inhibit contractions of pregnant human uterine tissue.[78] This may be because of the competitive effects of progesterone.

PRETERM LABOR

Preterm (premature) birth is defined as delivery between 20-37 weeks, it complicates 7%-10% of all deliveries.[79] The causes include intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, placenta previa, premature rupture of membrane, intraamniotic infection and spontaneous. It may reflect a normal break down of the normal mechanisms responsible for maintaining uterine quiescence throughout gestation.[80] Several mechanisms are proposed

Deficiency of choriodecidual 15-OH-PGDH enzyme, responsible for degradation of prostaglandins, leads to increased concentrations of PGE2 which reaches myometrium and initiates contractions.[81]

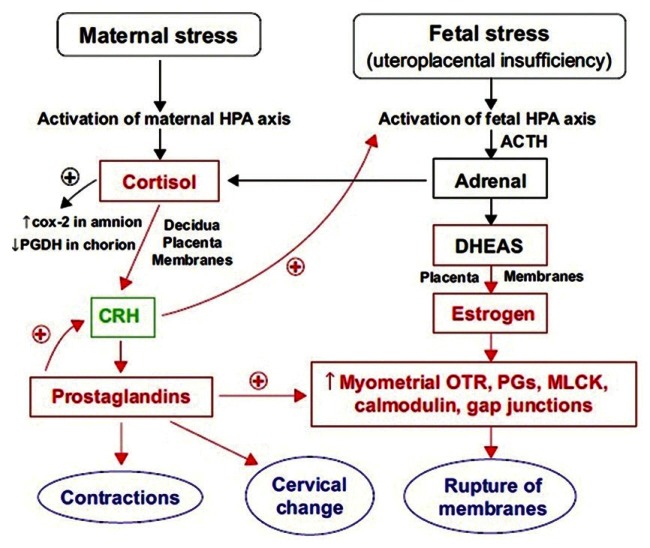

Maternal physical and psychological stress leads to premature activation of the maternal HPA axis and premature release of CRH with resultant programming of placental clock.[82,83] Chronic hypertension, severe pregnancy induced hypertension, uteroplacental insufficiency is variably associated with stress induced HPA axis activation[84,85] culminating in preterm labour [Figure 4].

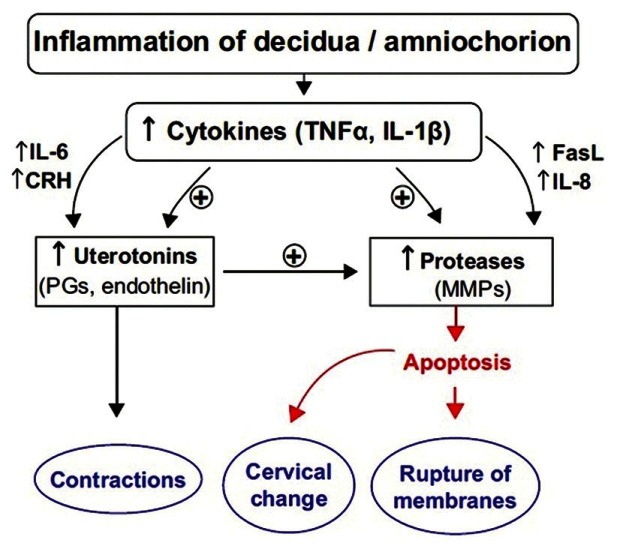

Genital infections affecting decidua/amniochorion lead to maternal or fetal inflammatory response.[86] The activated macrophages and granulocytes release inflammatory mediators like cytokines, (IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα), matrix metallo proteinases (MMP) (collagenase, gelatinase, stromelysin) and products of lipooxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathway.[87–90] Cytokines stimulate PG production and induces MMPs, which further weaken the fetal membranes and ripen the cervix by disrupting the rigid collagen matrix. Cutokine and eicosanoids accelerate each other's production. TNF-α additionally promotes apoptosis. Infection per se leads to reduction in 15-OH-PDGH enzyme levels aiding in preterm labour.[91] All these mediators ultimately result in premature rupture of membranes and overwhelmed normal parturition cascade leading to preterm labour [Figure 5].

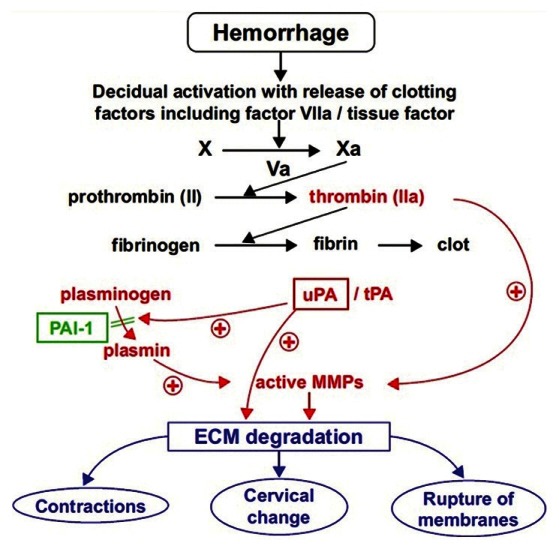

Decidual hemorrhage generates thrombin, which is a powerful uterotonic agent.[92] It stimulates myometrial contractions by activated phosphatidyl inositol signaling pathways[93] and also increases expression of plasminogen activator and MMPs[94] [Figure 6].

Excessive uterine stretching caused by multiple birth pregnancy/polyhydramnios generates a signal that transmits through cellular cytoskeleton and activates cellular protein kinase.[95] The acute distension also upregulates certain genes including an interferon-stimulated gene encoding a 54-kD protein, the gene for Huntington-interacting protein 2 (an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and a novel as yet unidentified transcript.[96]

Higher mid pregnancy CRH levels and a 4 week advancement in the higher levels of salivary or urinary estriol result in preterm labour.[97,98] Salivary estrogen has been suggested as a screen for the potential of preterm labour risk.[99]

Premature birth is associated with increased circulating relaxin levels.[100] Women who have superovulation with human menopausal gonadotrophins for either ovulation induction or in vitro fertilization have a significantly higher risk of premature birth. These women, who have multiple corpora lutea, have significant levels of hyperrelaxinemia. Women destined to have premature delivery have higher levels of relaxin at 30 weeks gestation than women who deliver at term.[100]

Figure 4.

Maternal and fetal HPA axis and stress induced preterm birth. COX-2: Cyclooxygenase 2, MLCK: Myosin light chain kinase, OTR: Oxytocin receptors, PG: Prostaglandin, PGDH: Prostaglandin dehydrogenase

Figure 5.

Inflammation of decidua-amniochorion and preterm labor. FasL: Fas ligand, CRH: Cortico Tropic Hormone, PG: Prostaglandin, MMP: Matrix Metallo Proteinase

Figure 6.

Hemorrhage and preterm labor. ECM: Extracellular matrix, MMP: Matrix Metallo Proteinase, PAI-1: Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, tPA: Tissue-type plasminogen activator, uPA: Urokinase plasminogen activator

POST TERM PREGNANCY

Post-term (prolonged) pregnancy is defined as a pregnancy that has extended to or beyond 42 weeks (294 days) from the first day of the last normal menstrual period or 14 days beyond the best obstetric estimate of the date of delivery. The most common cause of prolonged pregnancy is an error in gestational age dating. Risk factors include nulliparity and a previous post-term pregnancy, male fetus.[101,102] Rarer causes include placental sulfatase deficiency, fetal adrenal insufficiency, or fetal anencephaly. There is a definite underlying biologic or genetic basis, which is not yet clearly defined.[101] Both the fetus and the mother are at risk.[103,104] The complications include increased perinatal deaths,[105] infantile death,[106] neonatal encephalitis.[107] Recent consensus opinions recommend the routine induction of labour at an earlier gestation age, specifically 41 weeks' gestation.[106,108]

CONCLUSION

Labour is a complex physiologic process involving fetal, placental, and maternal signals. A variety of endocrine systems play a role in the maintenance of uterine quiescence and the onset of parturition, with its attendant increase in uterine contractility and cervical ripening. There are many factors that can tip the balance in favor of delivery early, late, or on time. These factors, such as prostaglandins or inflammatory cytokines, may directly affect the contractile mechanisms. Other factors, such as oxytocin, CRH, or relaxin, may indirectly alter the actions of complementary systems. The timely onset of labour and birth is an important determinant of perinatal outcome. Both preterm labour and delivery and post-term pregnancy are associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality. It is only with increased understanding of the processes of parturition that obstetric care providers will be able to further improve the safety of the birth process culminating in successful pregnancy outcomes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Liggins GC. Initiation of labor. Biol Neonate. 1989;55:366–94. doi: 10.1159/000242940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liggins GC, Fairclough RJ, Grieves SA, Kendall JZ, Knox BS. The mechanism of initiation of parturition in the ewe. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1973;29:111–59. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571129-6.50007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flint AP, Anderson AB, Steele PA, Turnbull AC. The mechanism by which fetal cortisol controls the onset of parturition in the sheep. Biochem Soc Trans. 1975;3:1189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorburn GD, Hollingworth SA, Hooper SB. The trigger for parturition in sheep: Fetal hypothalamus or placenta? J Dev Physiol. 1991;15:71–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews SG, Challis JR. Regulation of the hypothalamo -pituitary- adrenocortical axis in fetal sheep. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1996;7:239–46. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(96)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Challis JR. The control of labor. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:660–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challis JR, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:514–50. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez Bernal A, Rivera J, Europe-Finner GN, Phaneuf S, Asbóth G. Parturition: activation of stimulatory pathways or loss of uterine quiescence? Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:435–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garfield RE, Saade G, Buhimschi C, Buhimschi I, Shi L, Shi SQ, et al. Control and assessment of the uterus and cervix during pregnancy and labour. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:673–95. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanborn BM. Relationship of ion channel activity to control of myometrial calcium. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 2000;7:4–11. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauerstein CJ, Zauder HL. Autonomic innervation, sex steroids and uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1970;25:617–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masaki T. Endothelins: Homeostatic and compensating action in the circulating and endocrine system. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:256–68. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-3-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppert PC. Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;38:267–79. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challis JR, Lye SJ. Parturition. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 985–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue Y, Nakao K, Okabe K, Izumi H, Kanda S, Kitamura K, et al. Some electrical properties of human pregnant myometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:1090–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkington HC, Tonta MA, Brennecke SP, Coleman HA. Contractile activity, membrane potential, and cytoplasmic calcium in human uterine smooth muscle in the third trimester of pregnancy and during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1445–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkington HC, Tonta MA, Davies NK, Brennecke SP, Coleman HA. Hyperpolarization and slowing of the rate of contraction in human uterus in pregnancy by prostaglandins E2 and F2alpha: Involvement of the Na+pump. J Physiol. 1999;514:229–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.229af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakao K, Inoue Y, Okabe K, Kawarabayashi T, Kitamura K. Oxytocin enhances action potentials in pregnant human myometrium - A study with microelectrodes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:222–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young RC. A computer model of uterine contractions based on action potential propagation and intercellular calcium waves. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:604–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Challis JR, Lye SJ. Parturition. In: Knobil E, Neil JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 985–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner MO, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Tucker JM, Nelson KG, et al. The origin and outcome of preterm twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:553–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00455-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lye SJ, Ou CW, Teoh TG, Erb G, Stevens Y, Casper R, et al. The molecular basis of labour and tocolysis. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 1998;10:121–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoumakis E, Makrigiannakis A, Margioris AN, Stournaras C, Gravanis A. Endometrial corticotropin-releasing hormone. its potential autocrine and paracrine actions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;828:84–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petraglia F, Potter E, Cameron VA, Sutton S, Behan DP, Woods RJ, et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor-binding protein is produced by human placenta and intrauterine tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:919–24. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.4.8408466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SA, Brooks AN, Challis JR. Steroids modulate corticotropin-releasing hormone production in human fetal membranes and placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:825–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-4-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petraglia F, Coukos G, Volpe A, Genazzani AR, Vale W. Involvement of placental neurohormones in human parturition. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;622:331–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith R, Mesiano S, Chan EC, Brown S, Brown S, Jaffe RB. Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly and preferentially stimulates dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate secretion by human fetal adrenal cortical cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2916–20. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakravorty A, Mesiano S, Jaffe RB. Corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates P450 17 alpha-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase in human fetal adrenal cells via protein kinase C. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3732–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lockwood CJ, Radunovic N, Nastic D, Petkovic S, Aigner S, Berkowitz GS. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and related pituitary-adrenal axis hormones in fetal and maternal blood during the second half of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 1996;24:243–51. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1996.24.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins AV, Eben F, Wolfe CD, Schulte HM, Linton EA. Plasma measurements of corticotrophin-releasing hormone-binding protein in normal and abnormal human pregnancy. J Endocrinol. 1993;138:149–57. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1380149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathanielsz PW. Comparative studies on the initiation of labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;78:127–32. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giussani DA, Jenkins SL, Mecenas CA, Winter JA, Honnebier BO, Wu W, et al. Daily and hourly temporal association between delta4-androstenedione-induced preterm myometrial contractions and maternal plasma estradiol and oxytocin concentrations in the 0.8 gestation rhesus monkey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1050–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathanielsz PW, Jenkins SL, Tame JD, Winter JA, Guller S, Giussani DA. Local paracrine effects of estradiol are central to parturition in the rhesus monkey. Nat Med. 1998;4:456–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibb W. The role of prostaglandins in human parturition. Ann Med. 1998;30:235–41. doi: 10.3109/07853899809005850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grammatopoulos DK, Hillhouse EW. Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in onset of labor. Lancet. 1999;354:1546–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chwalisz K, Garfield RE. Role of nitric oxide in the uterus and cervix: Implications for the management of labor. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:448–57. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1998.26.6.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones SA, Brooks AN, Challis JR. Steroids modulate corticotrophin releasing factor production in human fetal membranes and placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;68:825–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-4-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones SA, Challis JR. Steroid, corticotrophin-releasing hormone, ACTH and prostaglandin interactions in the amnion and placenta of early pregnancy in man. J Endocrinol. 1990;125:153–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1250153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petraglia F, Florio P, Nappio C, Genazzani AR. Peptide signaling in the human placenta and membranes: autocrine, paracrine and endocrine mechanisms. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:156–86. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-2-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuchs AR, Fuchs F. Endocrinology of term and preterm labor. In: Fuchs AR, Fuchs F, Stabblefield P, editors. Preterm birth – causes, prevention and management. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 1993. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson M, Dudley DJ. Endocrine assays to predict preterm delivery. Clin Perinat. 1998;4:837–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrocelli T, Lye SJ. Regulation of transcripts encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, by estrogen and progesterone. Endocrinology. 1993;133:284–90. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.1.8391423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lye SJ, Nicholson BJ, Mascarenhas M, MacKenzie L, Petrocelli T. Increased expression of connexin-43 in the rat myometrium during labour is associated with an increase in the plasma estrogen: Progesterone ratio. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2380–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8389279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bale TL, Dorsa DM. Cloning, novel promoter sequence, and estrogen regulation of a rat oxytocin receptor gene. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1151–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Windmoller R, Lye SJ, Challis JR. Estradiol modulation of ovine uterine activity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;61:722–8. doi: 10.1139/y83-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsui K, Higashi K, Fukunaga K, Miyazaki K, Maeyama M, Miyamoto E. Hormone treatments and pregnancy alter myosin light chain kinase and calmodulin levels in rabbit myometrium. J Endocrinol. 1983;97:11–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0970011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madsen G, Zakar T, Ku CY, Sanborn BM, Smith R, Mesiano S. Prostaglandins differentially modulate progesterone receptor-A and-B expression in human myometrial cells: Evidence for prostaglandin-induced functional progesterone withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1010–3. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grazzini E, Guillon G, Mouillac B, Zingg HH. Inhibitions of oxytocin receptor function by direct binding of progesterone. Nature. 1998;392:509–12. doi: 10.1038/33176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Wilson JW, Mendelson CR. A decline in the levels of progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9518–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633616100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keirse MJ. Progestogen administration in pregnancy may prevent preterm delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:149–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, Dombrowski MP, Sibai B, Moawad AH, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha- hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:419–24. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leppert PC. Cervical softening, effacement and dilatation in a complex biochemical cascade. J Matern Fetal Med. 1992;1:213–23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell BF, Wong S. Changes in 17 beta,20 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity supporting an increase in the estrogen/progesterone ratio of human fetal membranes at parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1377–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Challis JR, Sloboda DM, Alfaidy N, Lye SJ, Gibb W, Patel FA, et al. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction. 2002;124:1–17. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karalis K, Goodwin G, Majzoub JA. Cortisol blockade of progesterone: A possible molecular mechanism involved in the initiation of human labour. Nat Med. 1996;2:556–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibb W. The role of prostaglandins in human parturition. Ann Med. 1998;30:235–41. doi: 10.3109/07853899809005850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gross G, Imamura T, Muglia LJ. Gene knockout mice in the study of parturition. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2000;7:88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olson DM, Skinner K, Challis JR. Prostaglandin output in relation to parturition by cells dispersed from human intrauterine tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:694–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-4-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skinner KA, Challis JR. Change is the synthesis and metabolism of prostaglandins by human fetal membranes and decidua in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:519–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Falcone T, Little AB. Placental synthesis of steroid hormones. In: Tulchinsky D, Little AB, editors. Maternal-fetal endocrinology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1994. pp. 10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olson DM, Skinner K, Challis JR. Estradiol-17 beta and 2-hydroxyestradiol-17 beta-induced differential production of prostaglandins by cells dispersed from human intrauterine tissues at parturition. Prostaglandins. 1983;25:639–51. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(83)90118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith SK, Kelly RW. The effect of the antiprogestins RU 486 and ZK 98734 on the synthesis and metabolism of prostaglandins F2 alpha and E2 in separated cells from early human decidua. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:527–34. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siler-Khodr TM, Kang IS, Koong MK. Dose-related action of estradiol on placental prostanoid prediction. Prostaglandins. 1996;51:387–401. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(96)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ishihara O, Matsuoka K, Kinoshita K, Sullivan MH, Elder MG. Interleukin-1 beta-stimulated PGE2 production from early first trimester human decidual cells is inhibited by dexamethasone and progesterone. Prostaglandins. 1995;49:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)00009-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pomini F, Caruso A, Challis JR. Interleukin-10 modifies the effects of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on the activity and expression of prostaglandin H synthase-2 and the NAD + -dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in cultured term human villous trophoblast and chorion trophoblast cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4645–51. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leake RD, Weitzman RE, Glatz TH, Fisher DA. Plasma oxytocin concentrations in men, nonpregnant women, and pregnant women before and during spontaneous labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;53:730–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-4-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fuchs AR, Fuchs F, Husslein P, Soloff MS. Oxytocin receptors in the human uterus during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150:734–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adachi S, Oku M. The regulation of oxytocin receptor expression in human myometrial monolayer culture. J Smooth Muscle Res. 1995;31:175–87. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.31.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chan WY, Powell AM, Hruby VJ. Antioxytocic and antiprostaglandin-releasing effects of oxytocin antagonists in pregnant rats and pregnant human myometrial strips. Endocrinology. 1982;111:48–54. doi: 10.1210/endo-111-1-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carsten ME, Miller JD. A new look at uterine muscle contraction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1303–15. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rivera J, López Bernal A, Varney M, Watson SP. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and oxytocin binding in human myometrium. Endocrinology. 1990;127:155–62. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chibbar R, Miller FD, Mitchell BF. Synthesis of oxytocin in amnion, chorion, and decidua may influence the timing of human parturition. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:185–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI116169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss G, Goldsmith LT. Reproductive endocrinology, surgery and technology. chapter 39. In: Adashi EY, Rock JA, Rosenwaks Z, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 827–39. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palejwala S, Stein D, Wojtczuk A, Weiss G, Goldsmith LT. Demonstration of a relaxin receptor and relaxin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation in human lower uterine segment fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1208–12. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldsmith LT, Weiss G, Palejwala S. The role of relaxin in preterm labor. Prenat Neonat Med. 1998;3:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szlachter N, O'Byrne E, Goldsmith L, Steinetz BG, Weiss G. Myometrial-inhibiting activity of relaxin containing extracts of human corpus luteum of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;136:584–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacLennan AH, Grant P. Human relaxin. in vitro response of human and pig myometrium. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:630–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Villar J, Ezcurra EJ, de la Fuente VG, Canpodonico L. Preterm delivery syndrome: The unmet need. Res Clin Forums. 1994;16:9–33. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Snegovskikh V, Park JS, Norwitz ER. Endocrinology of parturition. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:173–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matthews SG, Challis JR. Regulation of the hypothalamo- pituitary- adrenocortical axis in fetal sheep. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1996;7:239–46. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(96)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, et al. The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks' gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–92. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Korebrits C, Ramirez MM, Watson L, Brinkman E, Bocking AD, Challis JR. Maternal corticotropin-releasing hormone is increased with impending preterm birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1585–91. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Salafia CM, Ghidini A, Lopez-Zeno JA, Pezzullo JC, et al. Uteroplacental pathology and maternal arterial mean blood pressure in spontaneous prematurity. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1998;5:68–71. doi: 10.1016/S1071-5576(97)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kramer MS, McLean FH, Eason EL, Usher RH. Maternal nutrition and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:574–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dudley DJ. Pre-term labour: An intra-uterine inflammatory response syndrome? J Reprod Immunol. 1997;36:93–109. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(97)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Romero R, Emamian M, Wan M, Quintero R, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD. Prostaglandin concentrations in amniotic fluid of women with intra-amniotic infection and preterm labour. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1461–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moretti M, Sibai BM. Maternal and perinatal outcome of expectant management of premature rupture of membranes in the mid-trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:390–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Romero R, Durum S, Dinarello CA, Oyarzun E, Hobbins JC, Mitchell MD. Interleukin-1 stimulates prostaglandin biosynthesis by human amnion. Prostaglandins. 1989;37:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(89)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Van Mier CA, Sangha RK, Walton JC, Matthews SG, Keirse MJ, Challis JR. Immunoreactive 15-hydroxyprostaglandindehydrogenase (PGDH) is reduced in fetal membranes from patients at preterm delivery in the presence of infection. Placenta. 1996;17:291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elovitz M, Baron J, Phillippe M. The role of thrombin in preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1059–63. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Elovitz MA, Ascher-Landsberg J, Saunders T, Phillippe M. The mechanisms underlying the stimulatory effects of thrombin on myometrial smooth muscle. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:674–81. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rosen T, Schatz F, Kuczynshi E, Lam H, Koo AB, Lockwood CJ. Thrombin-enhanced matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression: A mechanism linking placental abruption with premature rupture of the membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:11–7. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.1.11.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ou CW, Orsino A, Lye SJ. Expression of connexin-43 and connexin-26 in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and labour is differentially regulated by mechanical and hormonal signals. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5398–407. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nemeth E, Millar LK, Bryant-Greenwood G. Fetal membrane distention: II. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:60–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Petraglia F, Florio P, Nappi C, Genazzani AR. Peptide signaling in human placenta and membranes: Autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:156–86. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-2-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weiss G. Endocrinology of parturition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4421–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goodwin TM. A role for estriol in human labor, term and preterm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:S208–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70702-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Petersen LK, Skajaa K, Uldbjerg N. Serum relaxin is a potential marker of preterm labor. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:292–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mogren I, Stenlund H, Högberg U. Recurrence of prolonged pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:253–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Divon MY, Ferber A, Nisell H, Westgren M. Male gender predisposes to prolongation of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1081–3. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith GC. Life-table analysis of the risk of perinatal death at term and post term in singleton pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:489–96. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.109735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Treger M, Hallak M, Silberstein T, Friger M, Katz M, Mazor M. Post-term pregnancy: Should induction of labour be considered before 42 weeks? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:50–3. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.1.50.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: Population based analysis. BMJ. 1999;319:287–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rand L, Robinson JN, Economy KE, Norwitz ER. Post-term induction of labour revisited. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:779–83. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, Alessandri LM, O'Sullivan F, Burton PR, et al. Antepartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: The Western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1549–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians -gynecologists. Number 55, September 2004 (replaces practice pattern number 6, October 1997). Management of Postterm Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:639–46. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200409000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]