Abstract

Purpose

In the past, numerous chemokines have been shown to be present in the expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) of patients with CP/CPPS. This study examined the functional effects of chemokines in the EPS of patients with CPPS.

Materials and Methods

The functional effects of EPS on human monocytes were studied by examining monocyte chemotaxis in response to MCP-1, a major chemoattractant previously identified in CP/CPPS. Effects on cellular signaling were determined by quantifying intracellular calcium elevation in monocytes and activation of NF-κB in benign prostate epithelial cells.

Results

Our results show that the MCP-1 present in EPS is non-functional, with an inability to mediate chemotaxis of human monocytes or mediate signaling in either monocytes or prostate epithelial cells. Moreover, this absence of functionality could be extended to other proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα, when incubated with the EPS from CPPS patients. The mechanism underlying this apparent ability to modulate pro-inflammatory cytokines involves heat labile extracellular proteases that mediate inhibition of both immune and prostate epithelial cell function.

Conclusions

These results may have implications for the design of specific diagnostics and therapeutics targeted at complete resolution of prostate inflammatory insults.

Keywords: Chronic pelvic pain syndrome, prostatitis, chemokines, inflammation, pelvic pain

INTRODUCTION

Prostatitis is the most frequent urologic diagnosis in men under the age of 50, accounting for 8% of all office visits to urologists. The majority of prostatitis cases are classified as chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS, NIH Category III) 1. Traditionally, inflammation in CPPS has been considered to be synonymous with the presence of leukocytes in EPS. However there has been an absence of correlation between the presence of leukocytes and the symptoms of CPPS in men 2, 3 or leukocytes in EPS and histological inflammation 4. Histological inflammation in CPPS, as studied in the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events (REDUCE) study, showed a small correlation with the overall NIH-CPSI score but no correlation with pain 5. In contrast, numerous studies have shown elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that in some instances have been correlated with the NIH-CPSI 6.

Chemokines are potent chemoattractant cytokines that are produced locally in tissues and direct the migration and homing of leukocytes. Tissue gradients of inflammatory chemokines attract and maintain inflammatory cells at sites of host challenge 7. The concurrent presence of chemokines in the EPS in the absence of inflammatory foci in the prostate is counterintuitive suggesting a need for critical examination of the microenvironment in the prostate at the functional level. We therefore exposed human monocytes and benign prostate epithelial cells to EPS from different patient cohorts and studied cell signaling and function in response to proinflammatory mediators. Our results suggest the existence of mechanisms that modulate pro-inflammatory mediators and limit inflammation.

METHODS

Clinical Samples

The criteria utilized for sample collection has been previously described 6. Following approval from Institutional Review Boards, EPS samples were collected by DRE from urology clinic patients who had no urological disease, BPH, CPPS IIIA (10 or more WBC/hpf in EPS) or CPPS IIIB (less than 10 WBC/hpf in EPS). Controls included men with no history or symptoms of urinary tract inflammation, palpably normal prostates and normal PSA values (less than 4.0 ng/ml) for patients 50 years old or older. Men with BPH had typical obstructing voiding symptoms of BPH and palpably enlarged prostates. The patients with BPH were subdivided by EPS WBC count. Men with CPPS had a history of pelvic or perineal pain with or without inflammation for at least 3 months.

Monocyte chemotaxis

Chemotaxis was performed in triplicate for 2 h in Boyden chambers with an optimized MCP-1 concentration of 50 ng/ml (R&D Systems). FMLP (100 nM) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the positive and PBS as negative control. Chemotaxis of monocytes induced by EPS was examined for 2–3 h. The fluids were diluted 1/10 before addition to the bottom chambers.

Cytokine quantification

Human MCP-1 (R&D Systems) ELISA kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. EPS was diluted appropriately in assay buffer and final concentrations were obtained by comparison with a standard curve.

Detection of intracellular calcium

Intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) was quantified in fura-2/AM-loaded primary human monocytes that were attached to coverslips and imaged by video fluorescence imaging 8. Fluorescence was analyzed in each experiment using MetaFluor software (Universal Imaging Corporation) from regions of interest9. Recombinant human MCP-1 (10ng/ml) was added directly to cells alone or in the presence of diluted EPS according to experimental design. For inhibitor experiments, EPS was pre-incubated with GM6001 (10 μM, Calbiochem), protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma) or fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 30 minutes at 25°C prior to addition to cells. [Ca2+]i elevation was calculated by subtracting the baseline [Ca2+]i from the maximal calcium value. In experiments using the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1, [Ca2+]I elevation was imaged using the fluorescent dye fluo-4 AM (5 μM). [Ca2+]I elevation was observed as change in fluo-4 AM fluorescence and expressed as change in fluorescence from baseline.

NF-κB reporter cell line

RWPE-1 cells were used to create the NF-κB reporter cell line as previously described 10. The increase in luciferase activity was expressed as change in NF-κB activity in relative light units (RLU).

Statistical analyses

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed by single factor ANOVA or two-way ANOVA with matching. Post test analysis was performed using the Tukey-Kramer test with p<0.05 being considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

EPS inhibits MCP-1 induced chemotaxis of human monocytes

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated elevated levels of the chemokine MCP-1 in EPS from CPPS patients 6. We set out to examine whether the elevation in MCP-1 was associated with increased functional activity of MCP-1 in EPS. Since MCP-1 is a well -known chemoattractant for immune cells, we isolated human monocytes from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers and examined chemotaxis in response to EPS from different patient cohorts. Pooled EPS from CPPS or BPH patients with 0, 1–10 or 10–25 leukocytes per high power field (HPF) were compared with EPS from control patients with non-prostate disease (penile pain). Chemotaxis was measured with phosphate buffered saline alone (negative control) and FMLP (positive control). EPS from CPPS and BPH patients were initially assayed by ELISA for MCP-1 levels followed by use in the chemotaxis assay. Contrary to our expectations we observed that EPS from CPPS patients did not show any appreciable increase in chemotaxis of monocytes compared to PBS, despite the presence of elevated levels of MCP-1 as measured using ELISA (Fig. 1A). To further examine the inability of MCP-1 in CPPS EPS to elicit chemotaxis, we spiked PBS and EPS with a known concentration of MCP-1 and subsequently examined monocyte chemotaxis. The presence of EPS from CPPS patients with 3–10 or greater than 10 leukocytes per HPF significantly inhibited MCP-1 induced monocyte chemotaxis compared to MCP-1 in PBS (Fig. 1A). In contrast, control EPS from patients with penile pain, spiked with the same concentration of MCP-1 produced robust monocyte chemotaxis that was not significantly different from MCP-1 in PBS (Fig. 1A). We also examined chemotaxis in BPH patients grouped in a manner similar to CPPS patients with regard to leukocytes in EPS. BPH EPS did not demonstrate any significant inhibition of MCP-1 induced chemotaxis (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that EPS from CPPS patients possess factors that are capable of inhibiting MCP-1 induced chemotaxis.

Figure 1. EPS from CPPS patients inhibit MCP-1 induced chemotaxis of human monocytes.

Pooled EPS from CPPS or BPH patients with 0, 1–10 or 10–25 leukocytes per high power field (HPF) were compared with EPS from control patients with non-prostate disease (penile pain). Chemotaxis was measured with phosphate buffered saline alone (negative control) and FMLP (positive control). EPS from CPPS, BPH were assayed initially by ELISA for MCP-1 levels followed by use in the chemotaxis assay. EPS diluted 1:10 in PBS, EPS spiked with MCP-1 and PBS spiked with MCP-1 were used to stimulate chemotaxis of human monocytes. The presence of EPS from CPPS patients significantly inhibited MCP-1 induced monocyte chemotaxis compared to MCP-1 in PBS (A). No such inhibition was observed upon incubation with prostatic fluid from BPH patients (B). Data is representative of at least three separate experiments with similar results. Statistical significance was examined by ANOVA and is indicated by *p<0.05 or **p<0.001.

EPS inhibits calcium signaling in human monocytes

We next examined whether the functional inhibition of MCP-1 induced chemotaxis observed was mediated by changes in human monocyte signaling. MCP-1 has been previously demonstrated to mediate monocyte activation through elevation of intracellular calcium, a second messenger that triggers numerous intracellular signaling pathways including chemotaxis 11. Human monocytes were loaded with fura-2 AM dye and intracellular calcium elevation was imaged using ratiometric methods. Monocytes treated with recombinant MCP-1 demonstrated a rapid increase in intracellular calcium levels that was however attenuated if the treatment was done simultaneously with EPS from CPPS patients (Fig. 2A). We examined whether the inhibitory factor in EPS was acting at the level of the monocytes or by interaction with the MCP-1 stimulus. To define the site of action monocytes and MCP-1 were separately preincubated with EPS from CPPS patients for 30 minutes. Monocytes incubated with EPS (EPS/MCP-1) showed an attenuated intracellular response to MCP-1 added to the medium (Fig. 2B). When MCP-1 was incubated with EPS for 30 minutes (EPS preincubated) and subsequently added to the monocytes, the calcium response was completely abolished. We next examined the response to a second stimuli of MCP-1 in all three experimental groups to identify whether the inhibitory effect could be overwhelmed by increasing concentrations of MCP-1. Repeated administration of MCP-1 (2nd stimulation) did not elicit any further calcium increase in EPS treated monocytes (Fig. 2B). However, the addition of the ionophore ionomycin (1μm) elicited a strong intracellular calcium response in these cells suggesting that the inhibitory effects were specific to the MCP-1 stimulus (data not shown). These results suggest that EPS from CPPS patients strongly inhibit the ability of MCP-1 to elicit signaling mechanisms in human monocytes that are required to mediate activation and chemotaxis.

Figure 2. EPS from CPPS patients inhibit MCP-1 induced intracellular calcium elevation in human monocytes.

Human monocytes were loaded with fura-2 AM dye and intracellular calcium elevation was imaged using ratiometric methods. Monocytes treated with 10ng/ml of recombinant MCP-1 (arrow) demonstrated a rapid increase in intracellular calcium levels (A) that was however attenuated if the treatment was done simultaneously with EPS from CPPS patients (A). When the MCP-1 was preincubated with EPS for 30 minutes before stimulation, calcium elevation was completely abolished (B). Repeated administration of MCP-1 (2nd stimulation) did not elicit any further calcium increase in EPS treated monocytes (B). Data shown is representative of at least three separate experiments with similar results.

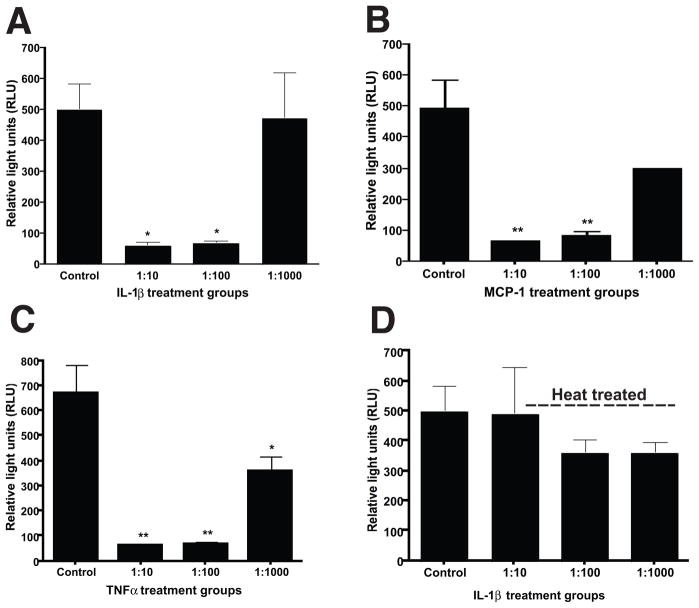

EPS modulates NF-κB activation in prostate epithelial cells

We next examined whether the inhibitory effects of CPPS EPS were restricted to human monocytes or extended to other cell types in the prostate. We examined the ability of human prostate epithelial cells to activate the transcription factor NF-κB, in the presence or absence of EPS from CPPS patients. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β (1ng/ml), MCP-1 (50ng/ml) and TNFα (1ng/ml) were used to stimulate NF-κB activation in RWPE-1 cells stably transformed with an NF-κB luciferase reporter construct. Cell cultures were treated for 4 hours either with the cytokine alone in PBS or in the presence of three different dilutions (1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000) of pooled EPS from CPPS patients. EPS significantly inhibited IL-1β (Fig. 3A), MCP-1 (Fig. 3B) and TNFα mediated NF-κB activation (Fig. 3C) in a concentration-dependent manner. To identify whether the inhibitory factor in EPS was heat labile, samples were pretreated with heat (56 °C for 30 minutes) prior to the addition to cells along with IL-1β. Heat pretreatment abrogated the ability of EPS to inhibit IL-1β mediated NF-κB activation (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the ability of EPS to modulate cellular activation is not restricted by cell type or stimulus. Furthermore, the inhibitory factor appears to be heat labile.

Figure 3. EPS from CPPS patients modulates NF-κB activation in benign prostate epithelial cells.

The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β (1ng/ml), MCP-1(50ng/ml) and TNFα (1ng/ml) were used to stimulate NF-κB activation in RWPE-1 cells stably transformed with an NF-κB luciferase reporter construct. Cell cultures were treated for 4 hours either with the cytokine alone in PBS or in the presence of three different dilutions (1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000) of pooled EPS from CPPS patients. EPS significantly inhibited IL-1β (A), MCP-1 (B) and TNFα mediated NF-κB activation in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast, pretreatment of EPS with heat (56 °C for 30 minutes) abrogated the ability of EPS to inhibit IL-1β mediated NF-κB activation (D). Data shown is the mean +/− SEM from three separate experiments. Statistical significance is indicated at *p<0.05 or **p<0.001.

EPS modulation of MCP-1 induced calcium elevation is sensitive to protease inhibition

Several potential mechanisms such as the presence of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and/or as yet undetermined protease enzymes were postulated to underlie the ability of EPS from CPPS to modulate chemotaxis, calcium elevation and NF-κB activation. We sought to identify some of these mechanisms in the human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1, a well-characterized cell line that reflects human monocyte/macrophage function. THP-1 cells were loaded with fluo-4 AM dye and intracellular calcium elevation was imaged. THP-1 cells treated with recombinant MCP-1 demonstrated a rapid increase in intracellular calcium levels that was significantly attenuated if MCP-1 treatment was done following preincubation of the EPS with MCP-1 for 30 minutes (Fig. 4A). In contrast, preincubation of the EPS with THP-1 cells prior to addition of the MCP-1 did not result in any significant inhibition of calcium elevation (Fig. 4A). We next preincubated EPS from CPPS patients for 30 minutes with GM6001, an MMP inhibitor; protease inhibitor cocktail; and fetal bovine serum, a natural protease inhibitor-containing source 12. Following the addition of MCP-1, EPS preincubated with the protease inhibitor cocktail as well as serum abrogated the ability of EPS from CPPS patients to inhibit MCP-1 induced calcium elevation. The inhibition was relieved by the subsequent addition of the ionophore ionomycin (1μm) (data not shown). In contrast, EPS preincubated with GM6001 significantly inhibited MCP-1 induced calcium elevation. These results suggest that the inhibitory factor in EPS from CPPS patients is a protease that acts on MCP-1 to inhibit function.

Figure 4. EPS modulation of MCP-1 signaling is sensitive to protease inhibition.

THP-1 cells loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM were treated with 10ng/ml of recombinant human MCP-1 and imaged at 488 nm using real-time video fluorescence microscopy and maximal fluorescence after MCP-1 treatment was subtracted from baseline. Preincubation of MCP-1 with CPPS EPS for 30 minutes prior to stimulation of THP-1 cells significantly (p<0.001) inhibited intracellular calcium elevation (A). Pretreatment of EPS with a protease inhibitor or fetal bovine serum (FBS) removed the inhibitory effect of EPS pretreatment on MCP-1 induced intracellular calcium elevation (B). Pretreatment of EPS with an MMP inhibitor (GM6001, 10μM) retained the inhibition of MCP-1 induced intracellular calcium elevation. Data shown is the mean +/− SEM from three separate experiments. Statistical significance is indicated at *p<0.05 or **p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the past numerous cytokines/chemokines have been shown to be present in the EPS of patients with CP/CPPS 13, 14. An important question in the pathogenesis of inflammation is how chemoattractant signals are shut down to restrict immune cell recruitment and to promote clearance of the inflammatory infiltrate. Previous studies from our group have demonstrated that the chemokine MCP-1 is elevated in CP/CPPS 6, but our present study suggests that the residual MCP-1 in the EPS is no longer competent to mediate cell signaling and chemotaxis. In initial studies we focused on the immunomodulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ to examine their potential roles in inhibiting MCP-1 induced chemotaxis. However, treatment of monocytes with neutralizing antibodies to these cytokines did not abrogate the inhibitory effects on MCP-1 induced chemotaxis (data not shown). An alternative mechanism for the loss of the chemoattractant signal is the proteolysis of the chemokine. Given our ability to still detect and quantify MCP-1, a proteolytic mechanism would necessarily render the chemokine functionally inactive while retaining the immunodominant epitope recognized in the ELISA. Evidence for such a mechanism comes from our results demonstrating the ability of protease inhibitors to cause a disinhibition of EPS effects on cell signaling in THP-1 cells. Interestingly, the ability to render inactive proinflammatory mediators was not restricted to MCP-1 and extended to IL-1β and TNFα suggesting common inhibitory mechanisms that had wide substrate specificity.

Chemokine inactivation and clearance have been previously demonstrated in vivo 15. The mechanism of inactivation utilized matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs are implicated in many physiological processes involving matrix turnover 16, but more recently, MMPs have been shown to be involved in the proteolytic susceptibility of signaling proteins such as MCP-3 17, and TNF-α 18. MMP processing of MCP-1, MCP-2, MCP-3, and MCP-4 have been shown to reduce the cell migration of THP-1 monocytic leukemia cells and pre-B cells transfected with CCR-1, CCR-2, and CCR-3 receptors 15. Cleaved chemokines retained their ability to bind cell surface receptors with only slightly altered Kds. Thus, MMP-processing of chemokines can lead to generation of stable and potent receptor antagonists. The antagonistic effects are achieved through competition for receptor occupancy, with subsequent desensitization as a result of trafficking of the ligand-receptor complex to endosomes 19. Thus, these mechanisms could largely explain the findings with clinical CPPS samples through the production of stable receptor antagonists that would inhibit chemotaxis, cell signaling and activation of proinflammatory transcription factors. However, in our study with the broad- spectrum inhibitor of MMPs, we observed a lack of disinhibition of cell signaling in THP-1 cells suggesting one of two possible conclusions. Either, MMPs are not involved in mediating the proteolysis of MCP-1 in EPS or MMPs or other extracellular proteases unaffected by GM6001 inhibition mediate the actions of EPS from CPPS patients. Future studies using defined protease inhibitors will address these questions.

The clinical implications of these studies are two fold. If MCP-1 is endogenously cleaved in CPPS patients to produce a truncated form of MCP-1, there is the potential to develop unique diagnostics that preferentially quantify the truncated form of MCP-1. Such a diagnostic test would be able to differentiate MCP-1 released by acute inflammatory processes such as acute prostatitis or BPH20 from that released in CP/CPPS. Truncated MCP-1 may also potentially function as an anti-inflammatory in CP/CPPS to inhibit the resolution of primary prostate insults. In such an instance, protease inhibitors could have a therapeutic role in promoting “good inflammation” and resolution of prostate injury.

CONCLUSIONS

Cytokines/chemokines have been shown to be consistently elevated in the EPS of patients with CP/CPPS 6 but histological signs of inflammation are not as consistently observed 5. This study demonstrates that the disparity between these two markers of inflammation may arise due to modulation of inflammation in the prostatic microenvironment. Our results show that the chemoattractant MCP-1 present in the EPS is non-functional, with an inability to mediate chemotaxis of human monocytes or mediate signaling in either monocytes or prostate epithelial cells. The mechanism underlying this apparent ability to modulate pro-inflammatory cytokines involves heat labile extracellular proteases that mediate inhibition of cell function. These results may have implications for the design of specific diagnostics and therapeutics targeted at resolution of prostate inflammatory insults.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Klumpp and Dr. William Muller for many helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK 5U01DK065277-05 (A.J.S) and 1K01 DK079019-01A2 (P.T), and NIH AR055240 (R.M.P) and AR056099 (S.S).

References

- 1.Collins MM, Stafford RS, O’Leary MP, et al. How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol. 1998;159:1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickel JC, Alexander RB, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Leukocytes and bacteria in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome compared to asymptomatic controls. J Urol. 2003;170:818. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082252.49374.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaeffer AJ, Knauss JS, Landis JR, et al. Leukocyte and bacterial counts do not correlate with severity of symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. J Urol. 2002;168:1048. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.True LD, Berger RE, Rothman I, et al. Prostate histopathology and the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective biopsy study. J Urol. 1999;162:2014. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickel JC, Roehrborn CG, O’Leary MP, et al. Examination of the relationship between symptoms of prostatitis and histological inflammation: baseline data from the REDUCE chemoprevention trial. J Urol. 2007;178:896. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desireddi NV, Campbell PL, Stern JA, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha as possible biomarkers for the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:1857. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foxman EF, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Multistep navigation and the combinatorial control of leukocyte chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thumbikat P, Dileepan T, Kannan MS, et al. Characterization of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica leukotoxin interaction with bovine alveolar macrophage beta2 integrins. Vet Res. 2005;36:771. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kundu SD, Lee C, Billips BK, et al. The toll-like receptor pathway: a novel mechanism of infection-induced carcinogenesis of prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 2008;68:223. doi: 10.1002/pros.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sozzani S, Luini W, Molino M, et al. The signal transduction pathway involved in the migration induced by a monocyte chemotactic cytokine. J Immunol. 1991;147:2215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimon A, Shamash Y, Shapiro B. The plasmin inhibitor of human plasma. IV. Its action on plasmin, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and thrombin. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:5102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochreiter WW, Nadler RB, Koch AE, et al. Evaluation of the cytokines interleukin 8 and epithelial neutrophil activating peptide 78 as indicators of inflammation in prostatic secretions. Urology. 2000;56:1025. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00844-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadler RB, Koch AE, Calhoun EA, et al. IL-1beta and TNF-alpha in prostatic secretions are indicators in the evaluation of men with chronic prostatitis. J Urol. 2000;164:214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuibban GA, Gong JH, Wong JP, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of monocyte chemoattractant proteins generates CC chemokine receptor antagonists with anti-inflammatory properties in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werb Z, Chin JR. Extracellular matrix remodeling during morphogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:110. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuibban GA, Gong JH, Tam EM, et al. Inflammation dampened by gelatinase A cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science. 2000;289:1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gearing AJ, Beckett P, Christodoulou M, et al. Processing of tumour necrosis factor-alpha precursor by metalloproteinases. Nature. 1994;370:555. doi: 10.1038/370555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong JH, Clark-Lewis I. Antagonists of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 identified by modification of functionally critical NH2-terminal residues. J Exp Med. 1995;181:631. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita K, Ewing CM, Getzenberg RH, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) is associated with prostatic growth dysregulation and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 2009 doi: 10.1002/pros.21081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]