Abstract

Objective

To use contemporary labor data to examine the labor patterns in a large, modern obstetric population in the United States.

Methods

Data were from the Consortium on Safe Labor, a multicenter retrospective study that abstracted detailed labor and delivery information from electronic medical records in 19 hospitals across the United States. A total of 62,415 parturients were selected who had a singleton term gestation, spontaneous onset of labor, vertex presentation, vaginal delivery, and a normal perinatal outcome. A repeated-measures analysis was used to construct average labor curves by parity. An interval-censored regression was used to estimate duration of labor stratified by cervical dilation at admission and centimeter by centimeter.

Results

Labor may take over 6 hours to progress from 4 to 5 cm and over 3 hours to progress from 5 to 6 cm of dilation. Nulliparas and multiparas appeared to progress at a similar pace before 6 cm. However, after 6 cm labor accelerated much faster in multiparas than in nulliparas. The 95th percentile of the 2nd stage of labor in nulliparas with and without epidural analgesia was 3.6 and 2.8 hours, respectively. A partogram for nulliparas is proposed.

Conclusion

In a large, contemporary population, the rate of cervical dilation accelerated after 6 cm and progress from 4 to 6 cm was far slower than previously described. Allowing labor to continue for a longer period before 6 cm of cervical dilation may reduce the rate of intrapartum and subsequent repeat cesarean deliveries in the United States.

Introduction

Defining normal and abnormal labor progression has been a long-standing challenge. In his landmark publications, Friedman was the first to depict a labor curve and divide the labor process into several stages and phases.1,2 Abnormal labor progression in the active phase was defined as cervical dilation < 1.2 cm/hour in nulliparas and < 1.5 cm/hour in multiparas. No appreciable change in cervical dilation in the presence of adequate uterine contraction > 2 hours was considered as labor arrest.3 These concepts have come to govern labor management.

However, these criteria created 50 years ago may no longer be applicable to contemporary obstetric populations and for current obstetric management.4 Increasing maternal age and maternal and fetal body sizes have made labor a more challenging process. Moreover, frequent obstetric interventions (induction, epidural analgesia and oxytocin use) may have altered the natural labor process. The purpose of this study was to use contemporary labor data in a large number of parturients with spontaneous onset of labor to examine the labor patterns and estimate duration of labor in the United States.

Materials and Methods

We used data from the Consortium on Safe Labor, a multicenter retrospective observational study that abstracted detailed labor and delivery information from electronic medical records in 12 clinical centers (with 19 hospitals) across 9 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) U.S. districts from 2002 to 2008. 87% of births occurred in 2005 – 2007. Detailed description of the study was provided elsewhere.5 Briefly, participating institutions extracted detailed information on maternal demographic characteristics, medical history, reproductive and prenatal history, labor and delivery summary, postpartum and newborn information. Information from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) was linked to the newborn records. Data on labor progression (repeated, time-stamped cervical dilation, station and effacement) were extracted from the electronic labor database. To make our study population reflect the overall U.S. obstetric population and to minimize the impact of the various number of births from different institutions, we assigned a weight to each subject based on ACOG district, maternal race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic and others), parity (nulliparas vs. multiparas) and plurality (singleton vs. multiple gestation). We first calculated the probability of each delivery with these four factors according to the 2004 National Natality data. Then, based on the number of subjects each hospital contributed to the database, we assigned a weight to each subject .5 We applied the weight to the current analysis. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

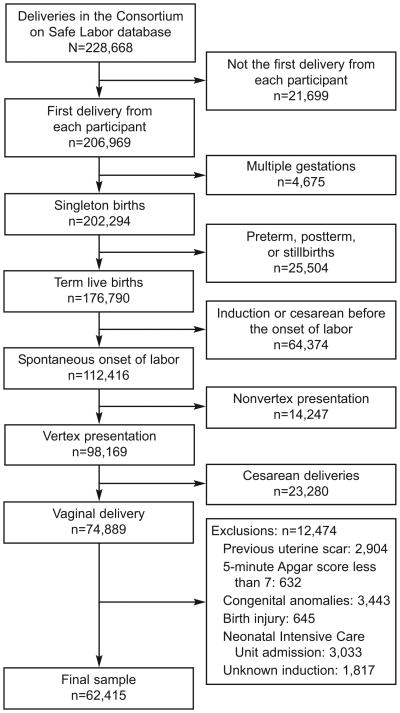

There were a total of 228,668 deliveries in the database. A total of 62,415 parturients were selected. Figure 1 depicts the sample selection process for the current analysis. Women were grouped by parity (0, 1, 2+). We used a repeated-measures analysis with 8th degree polynomial model to construct average labor curves by parity.6 In this analysis, the starting point was set at the first time when the dilation reached 10 cm (time = 0) and the time was calculated backwards (e.g., 60 minutes before the complete dilation, -60 minutes). After the labor curve models had been computed, the x-axis (time) was reverted to a positive value, i.e., instead of being -12 → 0 hours, it became 0 → 12 hours.

Figure 1.

Diagram of patient selection.

To estimate duration of labor, we used an interval-censored regression7 to estimate the distribution of times for progression from one integer centimeter of dilation to the next (called “traverse time”) with an assumption that the labor data are log-normally distributed.8 The median and 95th percentiles were calculated. Because multiparous women tended to be admitted at a more advanced stage labor than nulliparous women, many multiparous women did not have information on cervical dilation prior to 4 cm. Therefore, the labor curve for multiparous women started at 5 cm rather than at 4 cm as for nulliparous women.

Finally, to address the clinical experience wherein a woman is first observed at a given dilation and then measured periodically, we calculated cumulative duration of labor from admission to any given dilation up to the first 10 cm in nulliparas. The same interval censored regression approach was used. We provide the estimates according to the dilation at admission (2.0 or 2.5 cm, 3.0 or 3.5 cm, 4.0 or 4.5 cm, 5.0 or 5.5 cm) because women admitted at different dilation levels may have different patterns of labor progression. We then plotted the 95th percentiles of the duration of labor from admission as a partogram. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (PROC MIXED for the repeated-measures analysis and PROC LIFEREG for interval censored regression). Since the objective of this paper is to describe labor patterns and estimate duration of labor without comparing among various groups, no statistical tests were performed.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of women by parity. With increasing parity, both maternal age and body mass increased. The median cervical dilation at admission was 4 cm, 4.5 cm and 5 cm for parity 0, 1 and 2+, respectively, while the median effacement was 90%, 90% and 80%, respectively. Oxytocin for augmentation was used in nearly half of the women. Approximately 80% of women used epidural analgesia for labor pain. The median number of vaginal exams from admission to the first 10 cm was 5 for nulliparas and 4 for multiparas. The vast majority of women had a spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Parturients by Parity (weighted), Consortium on Safe Labor, 2002–2008.

| Parity 0 | Parity 1 | Parity 2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N - unweighted cohort | 27170 | 17850 | 17395 |

| N - weighted cohort | 453693 | 368131 | 311248 |

| Maternal race (%) | |||

| White | 60 | 55 | 51 |

| Black | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 26 | 29 |

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Others | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Maternal age (mean±SD, yrs) | 24.6 ± 5.8 | 27.7 ± 5.7 | 30.0 ± 5.4 |

| BMI before pregnancy (mean±SD, kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 4.6 | 24.2 ± 5.1 | 25.5 ± 5.6 |

| BMI at delivery (mean±SD, kg/m2) | 29.1 ± 5.0 | 29.6 ± 5.2 | 30.5 ± 5.5 |

| Cervical dilation at admission (cm) (median, 10th, 90th percentiles) | 4 (1, 7) | 4.5 (2, 8) | 5 (2, 8) |

| Effacement at admission (%) (median, 10th, 90th percentiles) | 90 (60, 100) | 90 (50, 100) | 80 (50, 100) |

| Station at admission (median, 10th, 90th percentiles) | -1 (-3, 0) | -1 (-3, 0) | -2 (-3, 0) |

| Oxytocin use in spontaneous labor (%) | 47 | 45 | 45 |

| Epidural analgesia (%) | 84 | 77 | 71 |

| Total number of vaginal exams in 1st stage (median, 10th, 90th percentiles) | 5 (1, 9) | 4 (1, 7) | 4 (1, 7) |

| Instrumental delivery (%) | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| Gestational age at delivery (mean±SD, weeks) | 39.3 ± 1.2 | 39.2 ± 1.2 | 39.1 ± 1.1 |

| Birthweight (mean±SD, grams) | 3296 ± 406 | 3384 ± 421 | 3410 ± 428 |

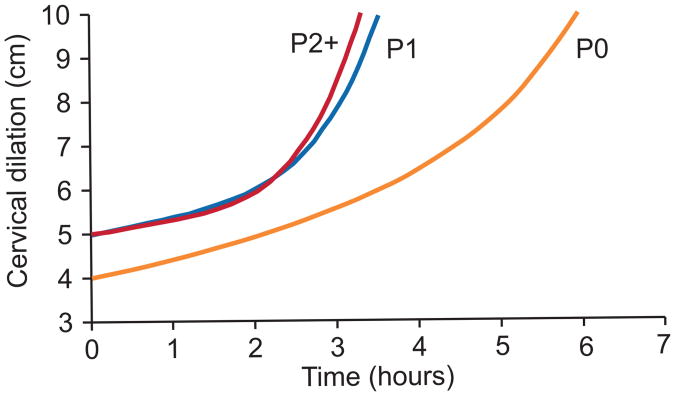

Figure 2 depicts the labor curves for various parities. In multiparas, labor appears to accelerate after 6 cm of cervical dilation. Parity 2+ entered the active phase earlier than Parity 1. In contrast, the average labor curve for nulliparas did not show a clear inflection point.

Figure 2.

Average labor curves by parity in singleton, term pregnancies with spontaneous onset of labor, vaginal delivery and normal neonatal outcomes. P0: nulliparas; P1: women of parity 1; P2+: women of parity 2 or higher.

Table 2 shows the duration of labor from one centimeter of dilation to the next. The 95th percentiles indicate that at 4 cm, it could take more than 6 hours to progress to 5 cm, while at 5 cm, it may take more than 3 hours to progress to 6 cm. Surprisingly, the medians and 95th percentiles of duration of labor before 6 cm were similar between nulliparas and multiparas. Only after 6 cm did multiparas show faster labor than nulliparas, which is consistent with the labor curves. This table also suggests that at 6 cm or later, almost all women who had vaginal delivery and normal neonatal outcomes had a 95th percentile of 1st stage of labor of less than 2 hours, particularly in multiparas. In the 2nd stage of labor, the 95th percentiles for nulliparas with and without epidural analgesia were 3.6 hours and 2.8 hours, respectively. The duration of the 2nd stage was much shorter in multiparas.

Table 2. Duration of Labor (in hours) by Parity in Spontaneous Onset of Labor.

| Cervical Dilation (cm) | Parity=0 Median (95th percentile) N=25624 | Parity=1 Median (95th percentile) N=16755 | Parity=2+ Median (95th percentile) N=16219 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 | 1.8 (8.1) | -- | -- |

| 4-5 | 1.3 (6.4) | 1.4 (7.3) | 1.4 (7.0) |

| 5-6 | 0.8 (3.2) | 0.8 (3.4) | 0.8 (3.4) |

| 6-7 | 0.6 (2.2) | 0.5 (1.9) | 0.5 (1.8) |

| 7-8 | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.2) |

| 8-9 | 0.5 (1.4) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.9) |

| 9-10 | 0.5 (1.8) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| 2nd stage with epidural analgesia | 1.1 (3.6) | 0.4 (2.0) | 0.3 (1.6) |

| 2nd stage without epidural analgesia | 0.6 (2.8) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.1 (1.1) |

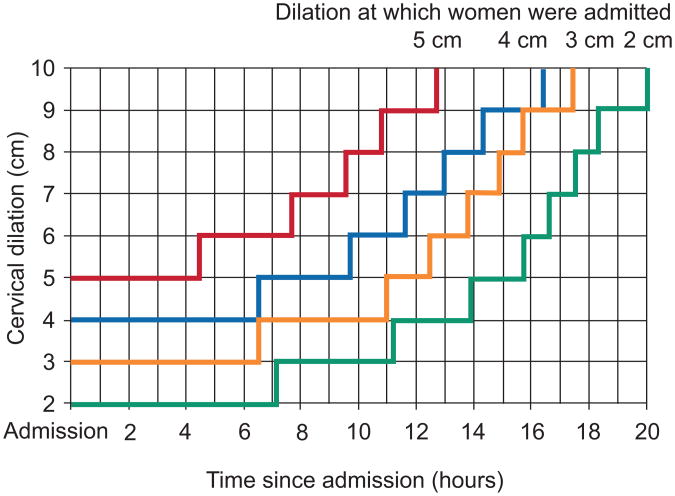

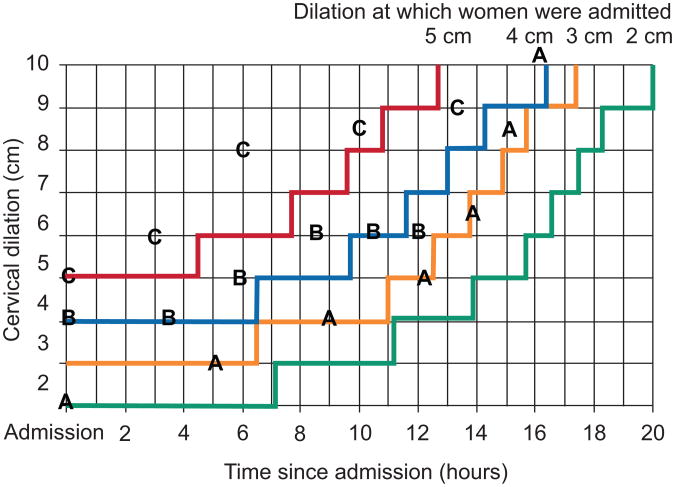

We then calculated cumulative duration of labor from admission to the first 10 cm in nulliparas. Table 3 presents the median and 95th percentile of duration of the 1st stage of labor. The 95th percentiles are also plotted as connected stair case lines in Figure 3. Each specific dilation at admission (2, 3, 4 or 5 cm) has its own corresponding line. At any time in the 1st stage, if a woman's labor crosses her corresponding 95th limit to the right side of the curve, her labor may be considered as protracted. Figure 4 illustrates 3 cases. Each letter represents a pelvic exam for the corresponding patient. Patient A was admitted at 2 cm. Her labor progressed to 10 cm without crossing the corresponding 95th percentile boundary. Patient B was admitted at 4 cm. Her labor progressed to 6 cm then stopped despite oxytocin augmentation. After 10 hours from admission, she passed the 95th percentile and may be considered as labor arrest. Patient C was admitted at 5 cm. She reached 9 cm after 13 hours but passed the 95th percentile.

Table 3. Duration of Labor (in hours) in Nulliparas with Spontaneous Onset of Labor.

| Cervical Dilation (cm) | Adm. at 2 or 2.5 cm Median (95th percentile) N=4247 | Adm. at 3 or 3.5 cm Median (95th percentile) N=6096 | Adm. at 4 or 4.5 cm Median (95th percentile) N=5550 | Adm. at 5 or 5.5 cm Median (95th percentile) N=2764 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adm. to 3 | 0.9 (7.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Adm. to 4 | 3.2 (11.2) | 1.0 (6.5) | NA | NA |

| Adm. to 5 | 5.0 (13.9) | 2.9 (11.0) | 0.9 (6.5) | NA |

| Adm. to 6 | 6.0 (15.7) | 4.2 (12.5) | 2.2 (9.7) | 0.6 (4.5) |

| Adm. to 7 | 6.6 (16.6) | 5.0 (13.8) | 3.2 (11.6) | 1.5 (7.7) |

| Adm. to 8 | 7.1 (17.5) | 5.6 (14.9) | 3.9 (13.0) | 2.4 (9.6) |

| Adm. to 9 | 7.6 (18.3) | 6.1 (15.7) | 4.5 (14.3) | 3.0 (10.8) |

| Adm. to 10 | 8.4 (20.0) | 6.9 (17.4) | 5.3 (16.4) | 3.8 (12.7) |

Figure 3.

The 95th percentiles of cumulative duration of labor from admission among singleton, term nulliparas with spontaneous onset of labor, vaginal delivery, and normal neonatal outcomes.

Figure 4.

Labor progression in 3 patients (A, B, C). Each letter represents a pelvic examination for the corresponding patient. The stair lines are the 95th percentile of cumulative duration of labor from admission at 2, 3, 4, 5 cm of cervical dilation, respectively.

Discussion

The definitions of “normal labor” and “labor arrest” have profound effects on labor management and cesarean delivery rate. Our study used data from a large number of contemporary parturients across the U.S. who had a singleton term pregnancy with spontaneous onset of labor, a vertex fetal presentation, vaginal delivery and normal neonatal outcomes. We found that labor may take over 6 hours to progress from 4 to 5 cm and over 3 hours to progress from 5 to 6 cm of dilation. Nulliparas and multiparas appeared to progress at a similar pace before 6 cm. However, after 6 cm labor accelerated much faster in multiparas than nulliparas. The 95th percentile of the 2nd stage of labor in nulliparas with and without epidural analgesia was 3.6 and 2.8 hours, respectively. Utilizing data from this study, we produced a partogram for contemporary nulliparas.

Labor curves and normal values in labor progression are still largely based on the work by Dr. Emanuel Friedman several decades ago.2,3 However, our study with a contemporary population observed several important differences from the classic Friedman curve.2 First, after having plotted a large number of labor curves, it became clear that there are a substantial number of parturients who may not have a consistent pattern of the active phase of labor, particularly in nulliparas. Labor may progress more gradually but still achieve vaginal delivery.

Second, even in women who had an active phase characterized by precipitous cervical dilation in the late 1st stage, the active phase often did not start until 6 cm or later. This seems to differ materially from prevailing concepts that the active phase starts before 4 cm2,3 and that 4 cm is a commonly used milestone.9 Rouse et al.10,11 defined the active phase in induced labor as cervical dilation at 4 cm with ≥ 90% effacement or 5 cm dilation regardless of effacement. However, Peisner and Rosen12 found that among women who had no active phase arrest, 50% of them entered active phase by 4 cm dilation; 74% by 5 cm and 89% by 6 cm. These findings point to the importance of separating an average starting point of active phase from a clinical diagnosis of labor arrest. Judging whether a woman is having labor protraction and arrest should not be based on a research definition of an average starting point or average duration of labor. Instead, an upper limit of what is considered “normal labor” should be used in patient management. As long as the labor is within a normal range and other maternal and fetal conditions are reassuring, a woman should be allowed to continue the labor process. Our study suggests that in the contemporary population, 6 cm rather than 4 cm of cervical dilation may be a more appropriate landmark for the start of the active phase.

Finally, consistent with clinical experience, our data demonstrate that cervical dilation often accelerates as labor advances. No appreciable change in dilation for 4 hours may be normal in early labor but probably too long after 6 cm (Table 2). This non-linear relationship should be reflected in the definition of labor arrest.

For a more objective evaluation of labor protraction and arrest, a partogram may be a useful tool. Such a tool was originally utilized to prevent prolonged and obstructed labor in developing countries.13,14 The central feature of the partogram recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) consists of two straight diagonal, parallel lines based on the phase of maximum slope in the Friedman curve. The alert line starts at 4 cm of cervical dilatation to the point of expected full dilatation at the rate of 1 cm per hour15, indicating that attention is needed if cervical dilation is slower than 1 cm per hour starting at 4 cm. The action line is parallel, and 4 hours to the right of the alert line. Several studies14-16, but not all17, have shown that the partogram reduces the risk of prolonged labor, cesarean sections and perinatal mortality in developing countries.

Our partogram differs from the one by WHO15 in that: (1) We do not consider the alert line necessary in the U.S. since most women give birth in the hospital setting; (2) Our 95th percentile lines, equivalent to the action line, are exponential-like stair lines rather than straight lines because cervical dilation is not recorded as a continuous measure. The progression patterns (exponential) are more consistent with the physiology of dilation acceleration in late 1st stage; and (3) Our partogram allows much slower labor progression before 6 cm of dilation but much shorter duration than 4 hours after 6 cm. Finally, in contrast to the purpose of the WHO partogram, our partogram is intended to prevent premature cesarean delivery. Its validity and usefulness have yet to be confirmed.

The limitations of the current study are worth mentioning. First, defining “normal labor” remains a challenge. In order to best define this process, we, therefore, examined labor patterns in women who had spontaneous onset of labor, vaginal delivery and normal neonatal outcomes. Second, given the very high frequency of obstetric intervention (induction and prelabor cesarean delivery) in contemporary practice, only a third of all births in our large population were comprised of women who were at term, had spontaneous onset of labor and vaginal deliveries. Third, since intrapartum cesarean deliveries were performed according to the prevailing definition of labor arrest, some cesarean deliveries may be performed too soon (before 6 cm), which can cause early censoring of observation. This censoring may have resulted in a bias towards a shorter labor, particularly at the 95th percentiles. Fourth, nearly half of the parturients included in our analysis were given oxytocin for augmentation, which may have altered the natural labor progression. Thus, findings from our study must be interpreted within the context of current obstetric practice. Finally, we recognize that assessment of cervical dilation is inherently somewhat subjective. The inaccuracy of cervical dilation is likely caused by random error, which increases standard error but does not necessarily biases the point estimate. Given the large number of subjects in our study, our point estimates (the average labor curve, median and 95th percentile) are stable.

The differences in study population and obstetric practice may partly explain why the contemporary labor curves differ substantially from those from 50 years ago18, even though exactly the same statistical method was used. Women are older and heavier, factors known to affect labor progress and duration. Labor appears to progress more slowly now than before, even though more labors are being treated with oxytocin for augmentation. The current study observed that the inflection point between latent and active phases on the labor curve emerges at a more advanced cervical dilation. For instance, the inflection point in multiparas previously was described as occurring at 5 or 5.5 cm 50 years ago18 but our data show that now it is at 6 or 6.5 cm. These findings indicate that the labor process in contemporary obstetric populations needs to be reevaluated and the definitions of “normal” and “abnormal” labor re-examined. Avoiding cesarean delivery before the active phase of labor is established may reduce the rate of cesarean delivery (intrapartum and subsequent repeat cesarean deliveries).

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The Consortium on Safe Labor was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, through a contract (Contract No. HHSN267200603425C).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Society for Maternal-fetal Medicine 29th Annual Scientific meeting, San Diego, California, January 26-31, 2009.

References

- 1.Friedman EA. The graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1568–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:567–89. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman EA. Labor: Clinical Evaluation and Management. 2nd. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Troendle J, Yancey MK. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:824–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy U, Laughon SK, Branch DW, Burkman R, Landy HJ, Hibbard JU, Haberman S, Ramirez MM, Bailit JL, Hoffman MK, Gregory KD, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Kominiarek M, Learman LA, Hatjis CG, Van Veldhuisen P. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol (in press) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowder KJ, Hand DJ. Analysis of Repeated Measures. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. Berlin: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahratian A, Troendle JF, Siega-Riz AM, Zhang J. Methodological challenges in studying labor progression. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:72–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers LL, Schiff M, Gorwoda JG. The length of active labor in normal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:355–9. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouse DJ, Owen J, Hauth JC. Criteria for failed labor induction: prospective evaluation of a standardized protocol. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:671–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin MG, Rouse DJ. What is a failed labor induction? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:585–93. 20. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200609000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peisner DB, Rosen MG. Transition from latent to active labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:448–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philpott RH, Castle WM. Cervicographs in the management of labour in primigravidae I: the alter line for detecting abnormal labour. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Common. 1972;79:592–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1972.tb14207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philpott RH, Castle WM. Cervicographs in the management of labour in primigravidae II: the action line and treatment of abnormal labour. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Common. 1972;79:599–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1972.tb14208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. World Health Organization partograph in management of labour. Lancet. 1994;343(8910):1399–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dujardin B, De Schampheleire I, Sene H, Ndiaye F. Value of the alert and action lines on the partgram. Lancet. 1992;339:1336–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91969-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth RMD. Effect of partogram use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labor at term. Cochroane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub2. Art.No.:CD 005461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Troendle J, Mikolajczyk R, Sundaram R, Beaver J, Fraser W. The natural history of the normal 1st stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:705–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d55925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]