Abstract

Background

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is commonly treated with 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid, and oxaliplatin or irinotecan. The multitargeted kinase inhibitor, regorafenib, was combined with chemotherapy as first- or second-line treatment of mCRC to assess safety and pharmacokinetics (primary objectives) and tumor response (secondary objective).

Patients and methods

Forty-five patients were treated every 2 weeks with 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 bolus then 2400 mg/m2 over 46 h, folinic acid 400 mg/m2, and either oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 or irinotecan 180 mg/m2. On days 4–10, patients received regorafenib 160 mg orally once daily.

Results

The median duration of treatment was 108 (range 2–345 days). Treatment was stopped for adverse events or death (17 patients), disease progression (11 patients), and consent withdrawal or investigator decision (11 patients). Six patients remained on regorafenib at data cutoff (two without chemotherapy). Drug-related adverse events occurred in 44 patients [grade ≥3 in 32 patients: mostly neutropenia (17 patients) and leukopenia, hand–foot skin reaction, and hypophosphatemia (four patients each)]. Thirty-three patients achieved disease control (partial response or stable disease) for a median of 126 (range 42–281 days).

Conclusion

Regorafenib had acceptable tolerability in combination with chemotherapy, with increased exposure of irinotecan and SN-38 but no significant effect on 5-fluorouracil or oxaliplatin pharmacokinetics.

Keywords: chemotherapy, colorectal cancer, combination therapy, regorafenib, tyrosine kinase inhibition

introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality globally [1]. Although death rates appear to be declining, 50%–60% of patients can be expected to develop metastatic disease, and most of these patients will require palliative systemic therapy [2, 3].

First-line therapy commonly involves the combination regimens of 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid, and either oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or irinotecan (FOLFIRI) [2, 3]; with median survival of up to 20 months, but 5-year survival not exceeding 10% [4]. Addition of targeted therapies, such as bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab, to FOLFOX or FOLFIRI can improve the results achieved with chemotherapy alone [2, 3, 5–7]. However, there is concern that the combination of chemotherapy with more than one targeted agent can be associated with reduced tolerability and no beneficial impact on efficacy [8, 9]. Hence, there is interest in identifying single-targeted therapies that can be used in association with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI to improve survival without imposing an unacceptable toxicity burden.

Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506; Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) is a novel oral multikinase inhibitor that blocks the activity of multiple protein kinases, including kinases involved in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis [vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) 1, 2, and 3, and angiopoietin-1 receptor], oncogenesis [stem cell growth factor receptor, proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase receptor Ret, Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine protein kinase, and serine/threonine kinase protein B-raf (BRAF), including BRAFV600E], and the tumor microenvironment [platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β and fibroblast growth factor receptor] [10]. Regorafenib has shown antitumor activity in preclinical xenograft models, including models of colorectal cancer [10]. The first study of regorafenib in humans demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and preliminary evidence of antitumor activity in patients with solid tumors [11]. In a phase I extended-cohort clinical trial, single-agent regorafenib was associated with stable disease in 19 of 27 assessable patients with heavily pretreated colorectal cancer [12]. Recently, a phase III trial (CORRECT) reported an increase in overall survival (OS) in regorafenib-treated patients, randomized against best supportive care, after progression on standard therapy (6.4 versus 5.0 months, respectively). This result led to the Food and Drug Administration approval for regorafenib monotherapy in the USA; European approval is pending [13].

We designed the present study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00934882) to explore whether addition of regorafenib to FOLFOX or FOLFIRI could be feasible as a treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), in terms of safety and pharmacokinetic interactions of the various drug components of the regimen. Preliminary data from this study were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, June 2011, in Chicago, IL, USA [14].

materials and methods

This multicenter study was undertaken at seven specialist oncology departments in Germany. The protocol and all amendments were reviewed and approved by each study site's independent ethics committee or institutional review board, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidance on Good Clinical Practice, as well as local and European legislation.

patients

Men or women with metastatic, histologically or cytologically confirmed colorectal cancer, for which FOLFOX or FOLFIRI was considered appropriate as first- or second-line treatment, were able to enter the study.

Participants had to have at least one measurable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0, with progressive disease (based on radiological assessment or clinical evaluation) evaluated within 4 weeks before the pre-study examination. Additional inclusion criteria included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, anticipated life expectancy of at least 12 weeks, and adequate bone marrow, liver, and renal function.

Exclusion criteria included more than one previous line of chemotherapy; FOLFOX or FOLFIRI treatment of patients who were scheduled to receive that regimen in the present study; radiotherapy, major surgery, or treatment with another investigational agent within 4 weeks before the study; major organ dysfunction or bleeding risks, such as therapeutic anticoagulation; significant traumatic injuries; or thromboembolic events before study entry.

treatments

The choice of the cytotoxic chemotherapy (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) was at the investigators' discretion. However, to ensure that pharmacokinetics and safety data were available from at least 12 patients receiving each regimen, we aimed to recruit a minimum of 20 participants for each combination. When 20 patients had been allocated to one regimen, all subsequent patients were allocated to the other regimen.

The treatment schedule was as follows: starting on days 1 and 15 of each 28-day cycle, all patients received d/l-folinic acid 400 mg/m2 as a 2-h intravenous (IV) infusion before an IV bolus injection of 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 followed by a 46-h infusion of 5-fluorouracil 2400 mg/m2. Patients in the FOLFOX group received oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 as a 2-h IV infusion at the same time as the folinic acid infusion. Patients in the FOLFIRI group received irinotecan 180 mg/m2 as a 1.5-h infusion starting 30 min after the start of the folinic acid infusion. On days 4–10 and 18–24 of each cycle, all patients received regorafenib 160 mg orally once daily. Treatment continued for at least six cycles or until tumor progression, unacceptable toxicity, consent withdrawal, or withdrawal from the study at the discretion of the investigator. Prespecified dose adjustments for each agent could be made to manage adverse events. If a patient required more than two dose reductions, treatment was discontinued.

assessments

The primary objectives of the study were to define the safety profile of regorafenib in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI and to determine the effect of regorafenib on the pharmacokinetics of the FOLFOX and FOLFIRI components.

All patients who had taken at least one dose of study drug (regorafenib and/or oxaliplatin or irinotecan and/or 5-fluorouracil) and had post-treatment data were assessable for safety. Adverse events were evaluated using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 3.0.

Pharmacokinetics were assessed before (cycle 1) and after (cycle 2) regorafenib treatment of irinotecan and its metabolite, SN-38, platinum (unbound and total), and 5-fluorouracil. Blood samples for pharmacokinetics were collected on day 1 of cycles 1 and 2 according to the following schedule: irinotecan and SN-38, before the dose and at 1, 2, 2.25, 2.5, 2.75, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h after onset of infusion; free and total platinum, before the dose and at 1, 2, 2.25, 2.5, 2.75, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, and 72 h after onset of oxaliplatin infusion; 5-fluorouracil, before the dose and at 5 min, 24 h, and 46 h (end of infusion), and 20 min 30 min, 45 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h after the end of infusion. Analysis of irinotecan and SN-38 was carried out using high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Platinum was assayed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. 5-Fluorouracil was assayed using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. All methods were validated according to US Food and Drug Administration guidelines [15].

Tumor response, evaluated using RECIST version 1.0, was assessed at the end of every second treatment cycle, starting at the end of cycle 2. A documented tumor response was confirmed at a minimum of 4 weeks after the response had first been recorded.

results

In total, 48 patients were enrolled between August 2009 and August 2010, with data cutoff in December 2010. Forty-five patients completed screening and received at least one dose of study medication (FOLFOX: n = 25 and FOLFIRI: n = 20). Baseline patient characteristics are tabulated in Table 1. At the data cutoff, six patients were still receiving regorafenib treatment. In the other 39 patients, reasons for treatment discontinuation were adverse events (n = 16), disease progression, recurrence, or relapse (n = 11), consent withdrawal (n = 6), investigator decision (n = 5; mostly for planned tumor surgery, n = 3), and death (n = 1). The median duration of treatment was 108 (FOLFOX: 107, range 10–273 days and FOLFIRI: 112, range 2–345 days).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Regorafenib + FOLFOX (n = 25) | Regorafenib + FOLFIRI (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 14 (56) | 13 (65) |

| Female | 11 (44) | 7 (35) |

| Median age, years (range) | 63 (42–80) | 68 (18–77) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, n (%)a | ||

| 0 | 11 (44) | 16 (80) |

| 1 | 12 (48) | 4 (20) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||

| Mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma | 3 (12) | 1 (5) |

| Adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified | 22 (88) | 19 (95) |

| Clinical/radiographic tumor status at entry, n (%) | ||

| Progressive disease | 22 (88) | 15 (75) |

| Stable disease | 3 (12) | 1 (5) |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (20) |

| Number of metastatic sites at screening, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 9 (36) | 4 (20) |

| 2 | 7 (28) | 10 (50) |

| 3 | 3 (12) | 5 (25) |

| 4 | 4 (16) | 1 (5) |

| 5 | 2 (8) | 0 |

| Treatment line, n (%) | ||

| First | 16 (64) | 15 (70) |

| Second | 9 (36) | 5 (30) |

aPerformance status data were missing from two patients in the FOLFOX group.

safety and tolerability

All 45 patients reported one or more adverse events, which were deemed to be related to at least one of the study drugs in 44 (98%) patients. Table 2 presents the incidence of drug-related adverse events by treatment and grade. Overall, the incidence of drug-related adverse events of any grade was similar between FOLFOX and FOLFIRI groups.

Table 2.

Incidence of drug-related, treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients overall

| Regorafenib + FOLFOX (n = 25) |

Regorafenib + FOLFIRI (n = 20) |

Total (n = 45) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| Any event, n (%) | 25 (100) | 19 (76) | 19 (95) | 13 (65) | 44 (98) | 32 (71) |

| Hematological, n (%) | ||||||

| Neutropeniaa | 11 (44) | 8 (32) | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | 22 (49) | 17 (38) |

| Leukopenia | 10 (40) | 2 (8) | 7 (35) | 2 (10) | 17 (38) | 4 (9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 4 (20) | 1 (5) | 9 (20) | 2 (4) |

| Anemia | 1 (4) | 0 | 4 (20) | 0 | 5 (11) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 13 (52) | 1 (4) | 12 (60) | 2 (10) | 25 (56) | 3 (7) |

| Mucositis | 10 (40) | 2 (8) | 7 (35) | 0 | 17 (38) | 2 (4) |

| Nausea | 10 (40) | 1 (4) | 5 (25) | 0 | 15 (33) | 1 (2) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (16) | 0 | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 9 (20) | 1 (2) |

| Vomiting | 4 (16) | 0 | 4 (20) | 0 | 8 (18) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 3 (15) | 0 | 7 (16) | 1 (2) |

| ALT elevation | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 4 (9) | 2 (4) |

| Weight loss | 1 (4) | 0 | 3 (15) | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 |

| Lipase elevation | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) |

| AST elevation | 2 (8) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Flatulence | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Heartburn | 0 | 0 | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Dermatological, n (%) | ||||||

| Hand–foot skin reaction | 9 (36) | 1 (4) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 16 (36) | 4 (9) |

| Alopecia | 2 (8) | 0 | 8 (40) | 0 | 10 (22) | 0 |

| Rash or desquamation | 5 (20) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0 | 7 (16) | 0 |

| Other events, n (%) | ||||||

| Fatigue | 7 (28) | 0 | 9 (45) | 0 | 16 (36) | 0 |

| Sensory neuropathy | 11 (44) | 1 (4) | 4 (20) | 0 | 15 (33) | 1 (2) |

| Voice changes | 7 (28) | 0 | 5 (25) | 0 | 12 (27) | 0 |

| Headache | 8 (32) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 9 (20) | 0 |

| Nose bleed | 3 (12) | 0 | 4 (20) | 0 | 7 (16) | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 0 | 6 (13) | 1 (2) |

| Hypertension | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 4 (20) | 1 (5) | 6 (13) | 3 (7) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 4 (16) | 3 (12) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 5 (11) | 4 (9) |

| Thrombosis, embolism | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) |

| Musculoskeletal/soft-tissue disorder | 2 (8) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 2 (8) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Cough | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0 | 3 (7) | 0 |

aOnly one patient had febrile neutropenia (grade 3); this patient was receiving FOLFIRI.

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

Thirty-two (71%) patients had drug-related adverse events of CTCAE grade 3 or higher (Table 2).

Twelve (27%) patients reported at least one drug-related serious adverse event, including three patients with thrombosis or embolism, two patients with diarrhea, and one patient each with allergic reaction, brain ischemia, empyema, hypertension, leukocytopenia, liver dysfunction, neutropenia, oral mucositis, pneumonia and raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Of the three (7%) patients who died during the study or within 30 days after the last dose of study treatment, only one death was attributed to an adverse event (hepatic toxicity), whereas the other two were due to disease progression. The most frequent drug-related adverse events leading to dose modification were neutropenia (n = 12; 27%), mucositis (n = 8; 18%), hand–foot skin reaction (n = 8; 18%), and leukopenia (n = 5; 11%).

Drug-related adverse events resulted in dose modification, dose interruption, or permanent discontinuation of study treatment in 31 (69%) patients overall (18 [72%] FOLFOX and 13 [65%] FOLFIRI). Dose reduction or dose interruption of at least one of the chemotherapy components was observed in 52% of patients treated with FOLFOX and 65% of patients receiving FOLFIRI. A dose reduction of 5-fluorouracil due to adverse events was necessary in 18% of administered cycles. 5-Fluorouracil administration was interrupted (omitted) in 8% of cycles. Oxaliplatin and irinotecan doses were reduced in 11% and 12% and interrupted in 11% and 5% of administered cycles, respectively.

pharmacokinetics

The primary pharmacokinetic parameters of irinotecan, SN-38, total and unbound platinum, and 5-fluorouracil are presented in Table 3. For irinotecan, area under the curve (AUC) was significantly higher in cycle 2 (following regorafenib dosing) than in cycle 1 (before regorafenib dosing); the ratio of AUC values (cycle 2:cycle 1) was 1.28 (90% confidence interval [CI] 1.06 –1.54). Cmax for irinotecan was only slightly increased, and t½ was unchanged. For SN–38, AUC was significantly higher in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 (ratio 1.44, 90% CI 1.12–1.85), while Cmax was unchanged.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetics of irinotecan, SN-38, total and unbound platinum, and 5-fluorouracil before (cycle 1) and after (cycle 2) dosing with regorafenib

| Parameter | Unit | Cycle 1 |

Cycle 2 |

Ratio (90% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric mean | % CV | Range | Geometric mean | % CV | Range | Cycle 2/Cycle 1 | ||

| Irinotecan (n = 11) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 10.7 | 24.2 | 7.4–15.6 | 13.8 | 35.6 | 8.5–28.7 | 1.28 (1.07–1.54) |

| Cmax | mg/l | 1.9 | 33.2 | 1.3–3.4 | 2.3 | 70.0 | 1.4–13.2 | 1.22 (0.80–1.85) |

| t½ | h | 8.5 | 27.3 | 5.2–11.9 | 7.8 | 26.2 | 4.7–10.9 | n.c. |

| SN-38 (n = 10) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 0.4 | 42.7 | 0.2–0.7 | 0.5 | 57.8 | 0.2–0.9 | 1.44 (1.12–1.84) |

| Cmax* | mg/l | 33.6 | 104.7 | 11.8–239.9 | 30.4 | 47.8 | 14.1–60.6 | 0.91 (0.55–1.50) |

| t½ | h | 16.8 | 39.1 | 9.4–34.1 | 19.3 | 66.6 | 7.7–55.9 | n.c. |

| Total platinum (n = 12) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 81.0 | 22.2 | 44.8–109.8 | 112.9 | 11.4 | 89.9–134.5 | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) |

| Cmax | mg/l | 2.2 | 22.8 | 1.2–2.7 | 2.4 | 17.5 | 1.7–3.2 | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) |

| t½ | h | 46.4 | 17.6 | 36.9–60.2 | 52.0 | 23.6 | 36.9–72.9 | n.c. |

| Unbound platinum (n = 10) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 4.2 | 39.0 | 1.6–5.3 | 4.9 | 15.2 | 4.2–6.6 | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) |

| Cmax | mg/l | 0.8 | 32.7 | 0.4–1.3 | 1.0 | 19.5 | 0.7–1.3 | 1.19 (0.96–1.47) |

| t½ | h | 17.2 | 18.2 | 10.8–22.1 | 19.0 | 17.7 | 15.0–29.0 | n.c. |

| 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX regimen) (n = 9) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 123.2 | 73.1 | 31.5–287.8 | 139.9 | 106.1 | 35.1–418.5 | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) |

| Cmax† | mg/l | 19.1 | 163.7 | 1.9–71.3 | 19.2 | 413.8 | 0.2–79.5 | 0.89 (0.50–1.61) |

| t½ | H | 0.4 | 513.0 | 0.1–9.3 | 2.4 | 1813.8 | 0.09–149.2 | |

| 5-fluorouracil (FOLFIRI regimen) (n = 4) | ||||||||

| AUC | mg × h/l | 258.6 | 79.4 | 112.6–569.8 | n.c. | |||

| Cmax | mg/l | 23.6 | 92.1 | 11.1–66.0 | 21.6 | 1275.9 | 1.2–222.8 | 0.92 (0.06–13.9) |

| t½ | H | 0.2 | 135.7 | 0.0–0.4 | n.c. | |||

*n = 11; †n = 12 for cycle 1 and 11 for cycle 2.

CV: coefficient of variance; AUC: area under the concentration–time curve; Cmax: maximum concentration; t½: elimination half-life; n.c.: not calculated.

efficacy

Thirty-eight patients were evaluable for tumor response (a secondary objective of this study) and were included in the efficacy analysis. Seven patients achieved a partial response (FOLFOX: n = 4 and FOLFIRI: n = 3). Twenty-six patients had stable disease as best response (FOLFOX: n = 14 and FOLFIRI: n = 12). Overall, disease control (i.e. partial response or stable disease) was achieved in 33 (87%) patients. In these patients, the median time without progression was 126 (range 42–281 days) in the whole population, 122.5 (range 42–188 days) for the FOLFOX group, and 126 (range 67–281 days) for the FOLFIRI group.

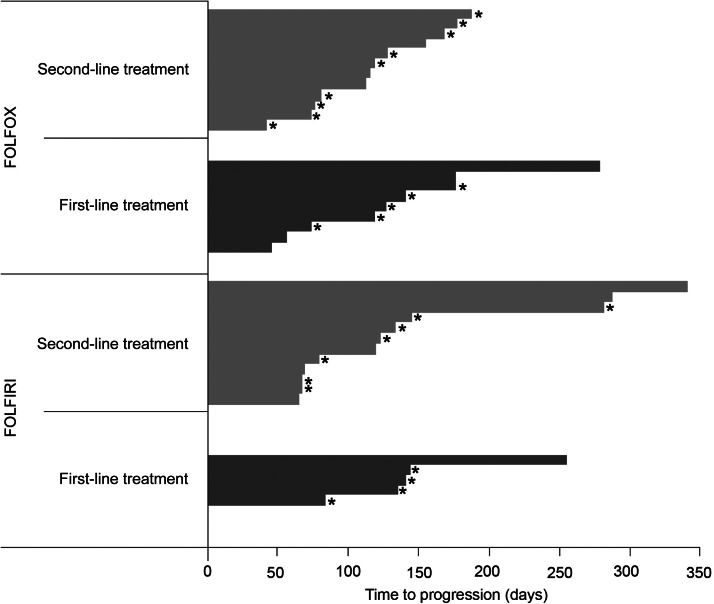

Median time to progression was 119 (range 45–340 days) overall, 116 (range 45–278 days) in the FOLFOX group, and 186.5 (range 64–340 days) in the FOLFIRI group. Figure 1 shows the time to progression for each patient.

Figure 1.

Time to progression in patients with disease progression or “censored at last contact”.

discussion

The results of this study indicate that regorafenib given sequentially after cytotoxic chemotherapy (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) has acceptable tolerability, with relatively little impact on the pharmacokinetics of the chemotherapy components.

Combination therapy did not appear to result in substantially worse toxicity than would be expected from each component individually. As expected, more than half of the patients experienced diarrhea (n = 25; 56%) and almost half of the patients (n = 22; 49%) had neutropenia, although only one patient had febrile neutropenia (in the FOLFIRI group). Relatively few drug-related adverse events were grade 3 or higher, most commonly neutropenia (n = 17; 38%) and hand–foot skin reaction, leukopenia, and hypophosphatemia (each n = 4; 9%).

The active metabolite of irinotecan, SN–38, is predominantly converted to an inactive metabolite by glucuronidation. As regorafenib is a strong inhibitor of the glucuronosyltransferases, UGT1A1 and UGT1A9, there was a potential for pharmacokinetic interaction. In anticipation of such an interaction, dosing of irinotecan was separated from regorafenib by 4 days. The present study indicated that irinotecan and SN-38 exposure was increased significantly following regorafenib dosing, even with a 4-day interval between irinotecan and regorafenib dosing. In line with the known elimination pathways of platinum and 5-fluorouracil, no pharmacokinetic interaction with regorafenib was expected, and this was largely corroborated by the results of the study. The slight increase in total platinum AUC at cycle 2 may be at least partially due to the long terminal elimination phase of platinum [16].

The regorafenib dosing regimen in this study was selected to reduce the risk of toxic effects and drug interactions by moderating the total monthly regorafenib dose and avoiding simultaneous dosing of regorafenib and chemotherapy, especially since regorafenib has two active metabolites (M2 and M5) with half-lives of 25 (regorafenib), 26–28 (M2), and 51–64 h (M5) [12]. This regorafenib schedule resulted in a total monthly dose of 2240 mg, which is lower than the 3360-mg total monthly dose in trials of single-agent regorafenib (which use a treatment schedule of 160 mg once daily for the first 21 days of each 28-day cycle). Patients could also have dose modifications of regorafenib or chemotherapy if deemed appropriate to manage toxic effects. The regimen may have achieved its aim of reducing the risk of toxic effects and drug interactions, but we acknowledge that the schedule can be difficult for patients to remember and requires careful instructions to achieve optimal adherence.

The median duration of disease control reported in this trial was similar in the FOLFOX and FOLFIRI groups (122.5 and 126 days, respectively). No clear difference was seen in progression-free survival (PFS) between patients receiving the first- or second-line treatment. In contrast, Tournigand et al. [17] reported median PFS of 8.5 and 2.5 months for first-line FOLFIRI and second-line FOLFIRI treatments, respectively, whereas for FOLFOX the median PFS was 8.0 and 4.2 months in first- and second-line treatments, respectively. For the present trial, it should be borne in mind that time to progression was not a primary end point, and patients were therefore not followed up long term: most observations were censored (13 of the 21 patients in the FOLFOX group and 11 of the 17 patients in the FOLFIRI group), making the interpretation of PFS data in this trial difficult.

Two additional factors may explain the rather low clinical efficacy observed in this trial. (i) The addition of regorafenib to standard treatment with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI may have resulted in a higher frequency of dose reductions and interruptions, resulting in reduced dose intensity. More than 50% of patients required a reduction of chemotherapy dose due to adverse events observed in this trial. This is higher than what has been reported with FOLFIRI (20.9%) and FOLFOX (14%) without the addition of targeted therapy [18, 19]. (ii) Normalization of the tumor vasculature through antiangiogenic treatment might improve tumor perfusion and, consequently, delivery of systemic chemotherapy [20]. However, significantly reduced tumor vascularity might result in inefficient uptake of cytotoxic agent in the tumor [21, 22]. In this regard, the scheduling of a targeted compound in relation to chemotherapy may influence the efficacy of the combination treatment. In vivo data demonstrate that the impact of scheduling and dosing sequence on antiangiogenic agents with chemotherapy may depend on the combined drugs and models used. When axitinib was combined with gemcitabine in a pancreatic xenograft model and with paclitaxel plus carboplatin in a xenograft model of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), tumor growth inhibition was highest with concurrent dosing of antiangiogenic and chemotherapy [23]. Similar data were obtained with vandetanib in combination with irinotecan in a colon cancer xenograft model [24]. On the other hand, docetaxel immediately followed by sunitinib in a human NSCLC xenograft model resulted in superior tumor growth inhibition compared with concurrent administration of these compounds [25]. We cannot exclude the possibility that a different dosing schedule of regorafenib and FOLFOX or FOLFIRI would have altered the efficacy profile of the combination treatments. Despite the clinical doses being extrapolated from preclinical pharmacokinetic studies, the human metabolism data suggest that dose reductions might be more suitable for further clinical testing in order to avoid extensive toxic effects.

Other trials have been undertaken to assess the impact of combining standard chemotherapy with antiangiogenic kinase inhibitors. In a phase I trial, Starling et al. [26] found that, in combination with FOLFIRI, continuous dosing of sunitinib was not feasible because of toxicity, while only the 37.5-mg/day sunitinib dose (and not the standard 50-mg/day dose) was tolerated using a schedule of 4 weeks on–2 weeks off treatment. A phase II trial of sunitinib plus FOLFIRI showed promising efficacy, although toxicity continued to be a concern [27], while a phase III trial combining sunitinib with FOLFIRI was discontinued prematurely for futility on the advice of the independent data monitoring committee [28]. For sorafenib, combination with either oxaliplatin, irinotecan, or cisplatin with gemcitabine has proven to be feasible in a phase I trial [29–31]. Data from randomized phase III trials in colorectal cancer are available for the combination of vatalanib with FOLFOX-4 [32, 33], semaxanib with 5-FU and leucovorin [34], brivanib with cetuximab [35], and cediranib with FOLFOX-6 [36] or with FOLFOX or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin [37]. Unfortunately, the addition of antiangiogenic treatment to standard chemotherapy did not result in an improvement in OS in any of these trials.

The present study was designed to explore the potential role of regorafenib given sequentially with cytotoxic chemotherapy for mCRC. The results indicate that the combination has acceptable tolerability. Further exploration of such regimens in larger clinical trials is ongoing. (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01289821, NCT01298570).

funding

This work was supported by Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. The editorial support was funded by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals.

disclosure

BS: travel reimbursement for the presentation of the preliminary data at ASCO; MK, OB, and JL: employee of Bayer Healthcare (sponsor of the study). The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Succinct Healthcare Communications for assistance in the preparation of the draft manuscript.

references

- 1.Globocan. Colorectal Cancer Fact Sheet 2008. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Colon Cancer. Version 3.2012. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Nordlinger B, Cervantes A. Advanced colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for treatment. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 2):v93–v97. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five-year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5721–5727. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Cutsem E, Rivera F, Berry S, et al. Safety and efficacy of first-line bevacizumab with FOLFOX, XELOX, FOLFIRI and fluoropyrimidines in metastatic colorectal cancer: the BEAT study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1842–1847. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocvirk J, Brodowicz T, Wrba F, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI in metastatic colorectal cancer: CECOG trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3133–3143. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyerhardt JA, Stuart K, Fuchs CS, et al. Phase II study of FOLFOX, bevacizumab and erlotinib as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1185–1189. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tol J, Koopman M, Cat M, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:563–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilhelm SM, Dumas J, Adnane L, et al. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506): a new oral multikinase inhibitor of angiogenic, stromal and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases with potent preclinical antitumor activity. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:245–255. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mross K, Frost A, Steinbild S, et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of regorafenib (BAY 73-4506), an inhibitor of oncogenic, angiogenic, and stromal kinases, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2658–2667. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strumberg D, Scheulen ME, Schultheis B, et al. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) in advanced colorectal cancer: a phase I study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1722–1727. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grothey A, Cutsem EV, Sobrero A, et al. for the CORRECT Study Group. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultheis B, Folprecht G, Kuhlmann J, et al. Phase I study of regorafenib sequentially administered with either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI in first-/second-line colorectal cancer patients. American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL, USA: 2011. Abstract 3585. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidance for Industry. Bioanalytical Method Validation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM); 2001. . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham MA, Lockwood GF, Greenslade D, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of oxaliplatin: a critical review. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1205–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tournigand C, André T, Achille E, et al. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:229–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, et al. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu T, Satoh T, Tamura K, et al. Oxaliplatin/fluorouracil/leucovorin (FOLFOX4 and modified FOLFOX6) in patients with refractory or advanced colorectal cancer: post-approval Japanese population experience. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:218–223. doi: 10.1007/s10147-007-0658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma J, Pulfer S, Li S, et al. Pharmacodynamic-mediated reduction of temozolomide tumor concentrations by the angiogenesis inhibitor TNP-470. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5491–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenton BM, Paoni SF, Ding I. Effect of VEGF receptor-2 antibody on vascular function and oxygenation in spontaneous and transplanted tumors. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu-Lowe D, Athias A, Hall C, et al. Impact of dosing schedule and dosing sequence on anti-tumor efficacy of combination therapy with the antiangiogenic agent (AA) axitinib (AG-013736) in xenograft tumor models of human pancreatic carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). AACR Annual Meeting 2009; ; Denver: American Association for Cancer Research, Abstract 144. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Troiani T, Serkova NJ, Gustafson DL, et al. Investigation of two dosing schedules of vandetanib (ZD6474), an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in combination with irinotecan in a human colon cancer xenograft model. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6450–6458. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen JG. Antitumor efficacy of sunitinib malate in concurrent and sequential combinations with standard chemotherapeutic agents in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) nonclinical models. AACR Annual Meeting 2009; ; Denver: American Association for Cancer Research, Abstract 1433. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starling N, Vázquez-Mazón F, Cunningham D, et al. A phase I study of sunitinib in combination with FOLFIRI in patients with untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:119–127. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mross K, Büchert M, Fasol U, et al. A preliminary report of a phase II study of folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan (FOLFIRI) plus sunitinib with toxicity, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, biomarker, imaging data in patients with colorectal cancer with liver metastases as 1st line treatment—a study of the CESAR Central European Society for Anticancer Drug Research. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49:96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of FOLFIRI Chemotherapy with or without Sunitinib in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00457691. 23rd August 2012, date last accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupsch P, Henning BF, Passarge K, et al. Results of a phase I trial of sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) in combination with oxaliplatin in patients with refractory solid tumors, including colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2005;5:188–196. doi: 10.3816/ccc.2005.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mross K, Steinbild S, Baas F, et al. Results from an in vitro and a clinical/pharmacological phase I study with the combination irinotecan and sorafenib. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultheis B, Kummer G, Zeth M, et al. Phase Ib study of sorafenib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with refractory solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:333–339. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hecht JR, Trarbach T, Hainsworth JD, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study of first-line oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy plus PTK787/ZK 222584, an oral vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1997–2003. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.4496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Cutsem E, Bajetta E, Valle J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without PTK787/ZK 222584 in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2004–2010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ClinicalTrials.gov. Leucovorin and Fluorouracil with or without SU5416 in Treating Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00004252. 23rd August 2012, date last accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siu LL, Shapiro JD, Jonker DJ, et al. Phase III randomized trial of cetuximab (CET) plus either brivanib alaninate (BRIV) or placebo in patients (pts) with metastatic (MET) chemotherapy refractory K-RAS wild-type (WT) colorectal carcinoma (CRC): the NCIC Clinical Trials Group and AGITG CO.20 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl 4) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.0543. 3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson JD, Botwood NA, Rothenberg ML, et al. Phase III Trial of FOLFOX plus bevacizumab or cediranib (AZD2171) as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2009;8:59–60. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2009.n.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoff PM, Hochhaus A, Pestalozzi BC, et al. Cediranib plus FOLFOX/CAPOX versus placebo plus FOLFOX/CAPOX in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized, double-blind, phase III study (HORIZON II) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3596–3603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.6031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]