Abstract

Background

In this meta-analysis, we evaluated associations between statins and recurrence-free survival (RFS) following treatment of localized prostate cancer, with attention to potential benefits among patients treated primarily with radiotherapy (RT) versus radical prostatectomy.

Patients and methods

We identified original studies examining the effect of statins on men who received definitive treatment of localized prostate cancer using a systematic search of the PubMed and EMBASE databases through August 2012. Our search yielded 17 eligible studies from 794 references; 13 studies with hazard ratios (HRs) for RFS were included in the formal meta-analysis.

Results

Overall, statins did not affect RFS (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.74–1.08). However, in RT patients (six studies), statins were associated with a statistically significant improvement in RFS (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.49–0.93); this benefit was not observed in radical prostatectomy patients (seven studies). Sensitivity analyses suggested that primary treatment modality may impact the effect of statins on prostate cancer recurrence.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis suggests a potentially beneficial effect of statins on prostate cancer patients treated with RT but not among radical prostatectomy patients. Although limited by the lack of randomized data, these results suggest that primary treatment modality should be considered in future studies examining associations between statins and oncologic outcomes.

Keywords: meta-analysis, prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, recurrence, statin

introduction

Statins or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors are widely used treatments for hypercholesterolemia. However, by inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, statins also inhibit the production of farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, two biochemical products essential for cell growth and proliferation [1, 2]. These and other potential anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties suggest that statins could also inhibit carcinogenesis and impact cancer outcomes [3]. Indeed, one large, population-based study recently demonstrated an association between statin use and reduced cancer-specific mortality across multiple cancer subtypes [4].

The effect of statin use on prostate cancer, in particular, is of interest given the overlapping demographics of this malignancy and hypercholesterolemia as well as the high prevalence of statin use (∼24 million Americans in 2003–2004 [5]). Since both diseases commonly afflict older men, many prostate cancer patients are already prescribed statins at the time of their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Previous studies that have examined the association of statin use with prostate cancer incidence have reached variable conclusions [6–10]. Meta-analyses examining this association have been also equivocal [11–16].

Several studies have found an inverse association between statin use and decreased incidence of more aggressive disease, defined as high grade or advanced disease [8, 11, 17]. Moreover, statins may also impact prostate cancer outcomes after definitive treatment; by targeting cholesterol synthesis, statins may decrease prostate cancer's ability to synthesize testosterone de novo and impede progression to metastatic disease [18, 19].

Recent observational studies have explored whether statins may have a role in reducing progression after diagnosis. However, these analyses were ill-equipped to evaluate the potentially modifying effects of primary treatment as most only examined outcomes following either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. Both radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy (either external beam or brachytherapy) are commonly employed as definitive treatment modalities for early-stage prostate cancer, and outcomes after each treatment may be affected by statin use differentially, especially given the hypothesis that statins may act as radiosensitizers [3]. As has been observed with androgen deprivation therapy, an adjuvant treatment that impacts outcome after radiotherapy (RT) may not affect the outcome after radical prostatectomy [20–22]. Thus, in order to comprehensively evaluate the association of statin use with prostate cancer recurrence and the potentially modifying effects of primary treatment, we undertook a meta-analysis of the available data.

methods

search methods

Search terms were designed by five authors (JDS, HP, RM, MS and RO) to include all studies that investigated the association of statin use with prostate cancer outcomes, using all relevant synonyms for prostate cancer, genitourinary malignancies, and both trade and generic drug names for all statins in clinical use. These search terms are fully detailed in the Appendix. The search was applied to PubMed (1965 to present) and EMBASE (1974 to present), with the last search run on 2 August 2012. All publications, including abstracts, were eligible for retrieval, with duplicate publications removed. In addition, six authors (JDS, HP, RM, MS, RH and RO) conducted a manual review of the reference sections of the retrieved articles in order to identify additional relevant studies.

selection criteria

All unpublished, published, in press, and in progress studies were initially targeted for review if they were identified in the PubMed or EMBASE search, reported primary data and investigated the association between statins and outcomes after diagnosis among men with initially localized, non-metastatic prostate cancer. Both full-text articles and abstracts were eligible. Epidemiological studies that did not report disease outcomes after diagnosis such as mortality, biochemical failure and disease-specific mortality according to statin use were excluded. Studies including metastatic prostate cancer patients at diagnosis or non-human subjects were also excluded. Language selection was limited to articles written in English, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and French. Each citation was assessed for inclusion independently by at least two out of six authors (JDS, HP, RM, MS, RH and RO), and any discrepancies were arbitrated by all authors. In studies that recorded outcomes for similar or overlapping cohorts, data from the publication with the longest follow-up time were utilized.

data extraction and analysis

Two independent reviewers extracted data from each study. Hazard ratio (HR) effect estimates were used to assess potential associations between statin use and prostate cancer recurrence following treatment. Biochemical recurrence-free survival (RFS) estimates were used when available; however, progression-free survival estimates were also utilized if biochemical data were not reported separately. We attempted to contact study authors by e-mail to obtain these data if not available from the published reports. Adjusted multivariate estimates were used in all cases. In one study [23], the multivariate result obtained by personal communication was discordant with the univariate analysis; these data were verified before inclusion. Summary HR measurements were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using both fixed-effects and DerSimonian and Laird random-effects modeling, which accounted for both within-study and between-study variation [24]. The standard error of the HRs was determined by dividing the difference of the upper and lower 95% CI values on the log scale by 3.92 (twice the value of the z-score for the 95% CI) [25]. We used Cochran's Q test to test for heterogeneity between studies, with a P value <0.10 considered statistically significant [26]. We also used the I2 test to quantify the proportion of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance [27, 28]. Negative values of I2 were set to zero, so that I2 resided between 0 and 100%. Potential sources of heterogeneity were explored through stratification by primary treatment modality (prostatectomy versus radiation therapy), random-effects meta-regression modeling, inference analysis and exclusion sensitivity analyses. Publication bias was evaluated using the Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test and Egger's regression asymmetry test [29, 30]. All P values were two-tailed with α = 0.05 to establish statistical significance.

This work was carried out in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology group [31] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) group [32]. STATA 11.1 was used to conduct all statistical analyses (STATA, College Station, TX).

results

study characteristics

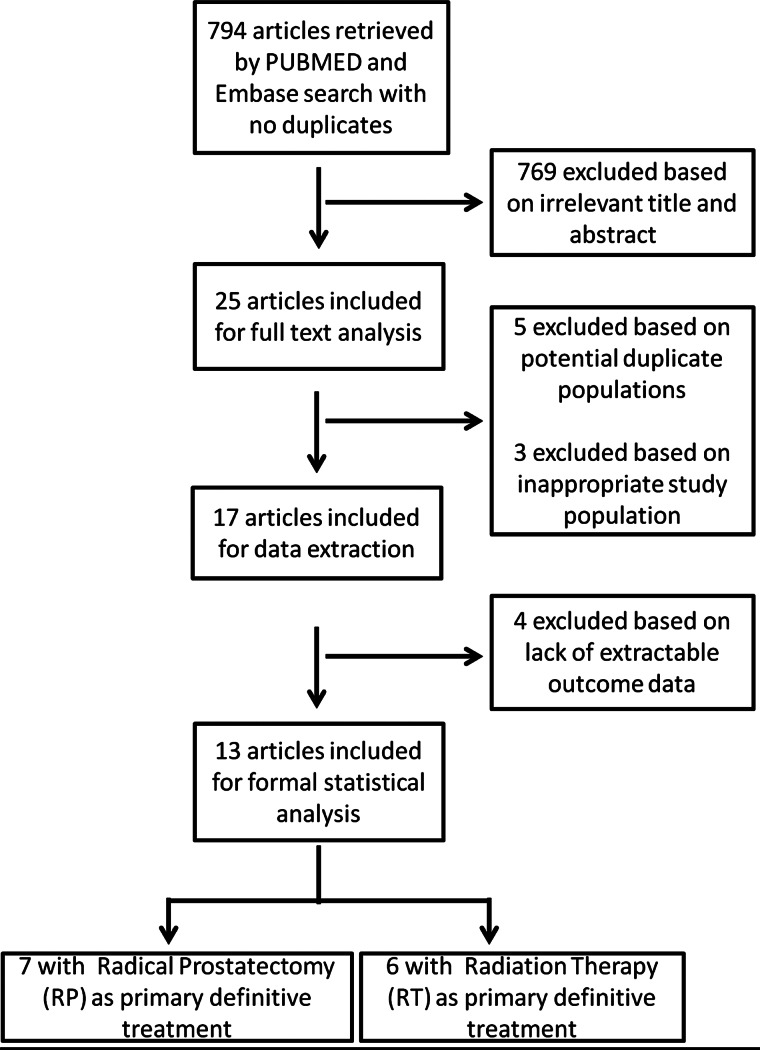

Our initial search yielded 794 citations (Figure 1). Of these, 769 were deemed to be irrelevant based on the title and/or abstract review, leaving 25 cohort studies for full article review. Additional reasons for exclusion following full-text review included: inseparable analysis of prostate cancer incidence (two studies) [8, 33], a population comprised of patients diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer [34] or utilization of an identical or subset of patients analyzed in another publication with longer follow-up (five studies) [23, 35–38].

Figure 1.

Literature search flow diagram based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [32].

Characteristics of the 17 remaining studies are shown in Table 1. Four of these studies were excluded from further statistical analyses [39–42] because they did not report a unified effect estimate for statin use on RFS. Among the 13 studies included in formal meta-analysis, seven included a population primarily treated with radical prostatectomy [43–49]. Patients in the other six studies were treated with RT—either external beam, brachytherapy or a combination of the two [10, 50–54]. One study in which all patients were treated with radical prostatectomy also utilized adjuvant RT in 26% of patients [43]. This particular study also reported that 18% of participants were treated with androgen deprivation. The studies in which RT was the primary treatment modality used androgen deprivation therapy in 26%–56% of participants [10, 50–53]. Four RT studies included in the formal meta-analysis utilized external beam radiation as primary treatment [10,51,52,54]; the remaining two studies included patients treated with primarily with brachytherapy, 10% and 57% of whom also received supplemental external beam treatment, respectively [50, 53].

Table 1.

Study characteristics of all extracted studies of the association between statin use and outcomes after prostate cancer diagnosis

| Source | No. of patients | No. of patients on statins (%) | Primary treatment(s) received | ADT | Outcome (s) with use of statins (95% confidence interval, CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alizadeh et al. [42]a | 381 | 172 (45%) | Radiotherapy (RT): EBRT (58%) or brachytherapy (42%) | 24% | Odds ratio for PSA>20: 0.29 (0.08–0.83)c |

| Gutt et al. [52] | 691 | 189 (27%) | RT: EBRT | 41% | Hazard ratio (HR) for BR: 0.43 (0.25–0.73)c |

| Hamilton et al. [43] | 1319 | 236 (18%) | Radical prostatectomy + 26% with adjuvant RT | 18% | HR for BR: 0.70 (0.50–0.97)c |

| Katz et al. [39]a | 7042 | 1824 (26%) | 65% Radical prostatectomy only 35% RT only |

NR | HR for ACM: Radical prostatectomy patients: 0.35 (0.21–0.58)c RT patients: 0.59 (0.37–0.94)c |

| Kollmeier et al. [10] | 1681 | 382 (23%) | RT: EBRT | 56% | HR for BR: 0.69 (0.50–0.97)c |

| Krane et al. [44] | 3828 | 1031 (27%) | Radical prostatectomy | NR | HR for BR: 0.99 (0.83–1.18)c |

| Ku et al. [46] | 609 | 79 (13%) | Radical prostatectomy | 0% | HR for BR: 1.18 (0.67–2.10)c |

| Lavery et al. [40]a$b | 1642 | 521 (32%) | Radical prostatectomy | NR | HR for BR: not significant |

| Mass et al. [49] | 1446 | 437 (30%) | Radical prostatectomy | 0% | HR for BR: 1.15 (0.82–1.61)c |

| Mondul et al. [47] | 2398 | 386 (16%) | Radical prostatectomy | 0% | HR for any recurrence: 1.00 (0.67–2.10)c |

| Moyad et al. [50] | 938 | 191 (20%) | RT: brachytherapy + 57% with supplemental EBRT | 41% | BR within 9 years: 1.6% (statins) versus 4.8%, log-rank P = 0.06 DSM within 9 years: 0% (statins) versus 4.1%, log-rank P = 0.12 ACM within 9 years: 14.2% (statins) versus 22.8%, log-rank P = 0.787 HR for BR: 1.50 (0.33–6.94)cd |

| Oh et al. [53]$b | 247 | 174 (70%) | RT: brachytherapy + 10% with supplemental EBRT | 26% | HR for BR: 0.29 (0.09–0.89)c |

| Rioja et al. [45]$b | 3748 | 1084 (29%) | Radical prostatectomy | 0% | HR for BR: 1.15 (0.89–1.50)c |

| Ritch et al. [48] | 1261 | 281 (22%) | Radical prostatectomy | 0% | HR for BR: 1.54 (1.0–2.2)c |

| Sharma et al. [41]a$b | 914 | 264 (29%) | RT: EBRT | 0% | HR for BR: 0.783e, P = 0.35c; 1.1016f, P = 0.94c HR for DSM: 2.747e, P = 0.25c; 2.365f, P = 0.32c HR for ACM: 0.186e, P = 0.001c; 1.032f, P = 0.90c |

| Soto et al. [51] | 968 | 220 (23%) | RT: EBRT | 29% | HR for any recurrence: 1.1 (0.8–1.6)c |

| Zaorsky et al. [54] | 2051 | 691 (34%) | RT: EBRT | 0% | BR within 18 months: 3.3% (statins) versus 11.4% Odds ratio for BR within 18 months: 0.41 (0.25–0.65) HR for BR: 0.63 (0.49–0.82)d |

aExcluded from formal meta-analyses due to lack of extractable, comparable data specific to the hazard of first recurrence based on any statin use.

$bAbstract only.

cMultivariate adjusted effect estimate.

dObtained by correspondence with primary authors.

ePost-RT statin use only.

fPre-RT statin use only.

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; EBRT, external beam RT; BR, biochemical recurrence; NR, not reported; ACM, all-cause mortality; DSM, disease-specific mortality.

quantitative data synthesis

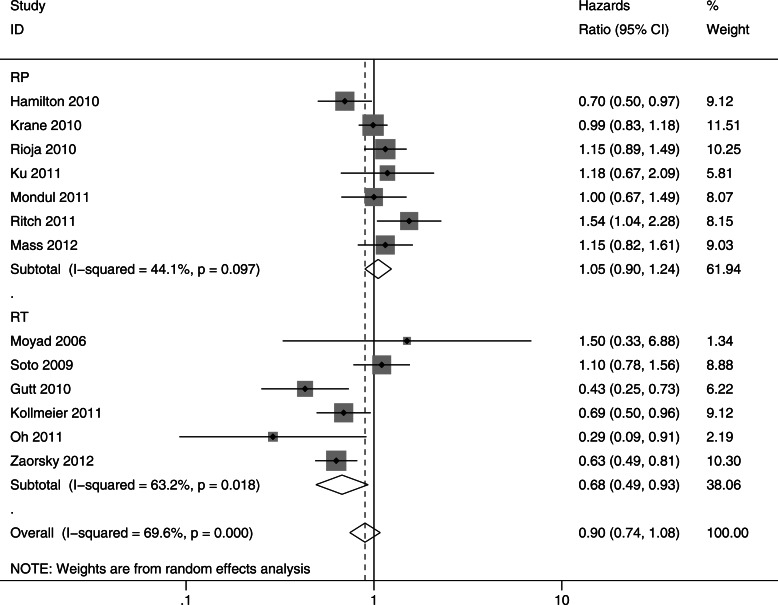

In most studies, the prevalence of statin use ranged from 20 to 35%, although it was 70% in the study by Oh et al. [53] Overall, there was no association between statin use and recurrence after prostate cancer diagnosis [HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.74–1.08] (Figure 2). The association was null among the men who underwent radical prostatectomy as primary therapy (HR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.90–1.24). However, among men who underwent radiation therapy as the primary treatment, statin users had a statistically significantly lower risk of recurrence compared with non-users (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.49–0.93).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating association of statins with recurrence-free survival (RFS), stratified by primary treatment modality. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported on a logarithmic scale. Pooled estimates are from a random-effects model. RT, radiotherapy; RP, radical prostatectomy.

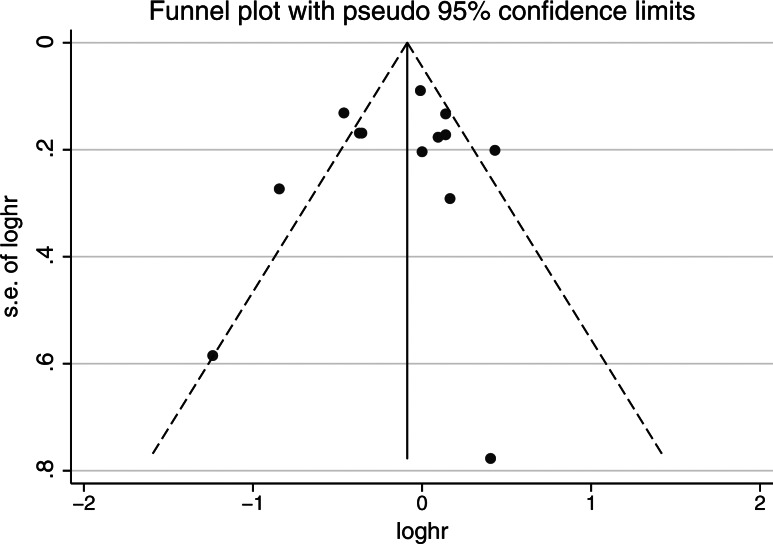

There was no clear evidence of publication bias found on the funnel plot (Figure 3), the Begg rank correlation method (P = 0.807) or the Egger weighted regression method (P = 0.624). There was evidence of significant heterogeneity overall (I2 = 69.6%, P = 0.001) and in studies including RT patients only (I2 = 63.2%, P = 0.018). Meta-regression investigating potential sources of heterogeneity demonstrated that primary treatment modality, publication type (complete manuscript versus abstract), total sample size and publication year were not significantly associated with lower risk of recurrence (data not shown). Among RT studies, the use of androgen deprivation therapy also did not significantly influence the association between statin use and recurrence.

Figure 3.

Publication bias assessed by the funnel plot.

We undertook sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. Fixed-effects models were consistent with random-effects models, showing that statin use was not associated with recurrence among all studies (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84–1.01), but was associated with significantly decreased recurrence in patients treated primarily with RT (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59–0.83). Inference analyses omitting any one publication did not significantly change the overall treatment-specific summary estimate for radical prostatectomy or RT studies. However, omitting Hamilton et al. [43], in which 26% of the RP patients also received adjuvant RT, led to a significant effect modification of treatment modality on the association between statins and recurrence (P = 0.043).

discussion

In this comprehensive meta-analysis among men following definitive treatment of localized prostate cancer, we found no overall association between statin use and recurrence. In a planned subgroup analysis of studies by treatment modality, there was no association with statin use and recurrence among men who underwent radical prostatectomy as primary therapy. In contrast, among men for whom RT was the primary treatment modality, there was a statistically significant 32% lower risk of recurrence among statin users. Furthermore, after excluding the surgical study that contained a significant proportion of irradiated patients, there was a statistically significant difference in effect estimates for statins by treatment modality. Meta-regression failed to demonstrate significant effects of study characteristics, including publication type, total sample size and publication year on the outcome. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to address this topic.

A benefit of statin use limited to patients treated with RT could potentially be explained by statin-induced radiosensitizing effects. The combination of statins and ionizing radiation has been shown to increase prostate cancer cell death in both in vitro and in vivo models [18, 52, 55]. One postulated mechanism for this radiosensitization involves the MYC oncogene, as statins in combination with radiation increase cancer cell death while decreasing cellular MYC levels in vitro [55]. The addition of the HMG-CoA bypass product mevalonate reverses both the increased cancer cell death and decreased MYC levels [55]. Statin use may also promote autophagy pathways that play a synergistic role with radiation in promoting prostate cancer cell death [56].

Given the antineoplastic properties previously attributed to statins, the lack of benefit of statin use on prostate cancer recurrence in patients treated with radical prostatectomy is somewhat unexpected. Statins' antineoplastic effects may be context-dependent, and therefore, may be subtle or even non-existent in the setting of radical prostatectomy. Such differential benefit by treatment modality has been observed for adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy; no consistent benefit has been observed following radical prostatectomy, although a clear survival benefit exists in the setting of RT [20, 21, 57]. Although radiation was not a significant modifier of the association between statin use and cancer-specific mortality in a recently published analysis [4], this study included a heterogeneous variety of cancer types and many patients who were likely treated in the metastatic setting. Furthermore, the data on treatment with chemotherapy or RT were missing in up to 72% of patients [58].

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several factors. First, the available literature was limited to observational cohort studies, which may be subject to bias and confounding, although we used multivariate adjusted HRs to account for this potential source of bias. Second, there was significant heterogeneity among studies that may reflect the different methodologies and patient characteristics of the studies included. We sought to address this problem by using random-effects modeling to attenuate the impact of this heterogeneity on the validity of the pooled results. Third, we excluded four studies that addressed our study question but failed to report a unified effect estimate for recurrence as a function of peri-treatment statin use. Since these studies were not included in our quantitative analysis, the power and precision of our results were likely reduced. Indeed, in line with our current findings, among the studies that were excluded due to their lack of a unified effect estimate for statin use on RFS, one reported a non-significant effect of statins on biochemical recurrence among men treated with radical prostatectomy [40]. The other three excluded studies either reported only on all-cause mortality [39] or PSA at diagnosis [42], or further subdivided outcome based on the timing of statin use [41], making direct comparisons with other studies impossible.

Despite these limitations, carrying out a meta-analysis allowed us to compare associations between statin use and prostate cancer recurrence in patients treated with radical prostatectomy with the effect of statins on patients treated with RT. In contrast, previous individual studies reported in the literature were predominantly limited to a single-definitive modality, and therefore could not investigate effect modification due to treatment type. There was no clear evidence of publication bias, which is unsurprising given our broad search criteria and inclusion of abstracts unaccompanied by complete manuscripts. Our subgroup analysis demonstrated a differential effect of statins on RFS in patients treated with RT when compared with radical prostatectomy. This suggests that associations between statin use and prostate cancer outcomes are less likely to be due to statins' potential ability to artificially lower PSA levels as has been suggested previously [59, 60], as such an artifactual effect of statins would uniformly decrease recurrence in both prostatectomy and RT patients.

In summary, our meta-analysis demonstrates that statin use is not associated with a significant effect on recurrence among all patients definitively treated for prostate cancer. Intriguingly, a benefit was noted in patients primarily treated with RT; this observation somewhat reconciles the seemingly disparate and conflicting results noted in prior observational studies on statin use and prostate cancer recurrence. Though the results of this meta-analysis should be approached with caution due to the inherent biases of observational studies and the lack of randomized, controlled trials, our results suggest that treatment modality should be considered a factor in future studies examining the association of statins with prostate cancer outcomes. Since widespread use of statins has led to the identification of unexpected potential long-term side-effects such as diabetes [61], it is even more important to identify those subsets of patients most likely to benefit from an antineoplastic effect in future confirmatory, randomized studies.

funding

JDS is supported by NIH Training Grant 5 T32 CA 9001–36; LAM is supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Chung Hsieh and Dr Julie Goodman for their guidance, as well as Dr Gregory Merrick, Dr Mark Buyyounouski and Ms Tianyu Li for providing additional HR data.

appendix

PubMed search terms:

(‘‘Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase

Inhibitors ‘‘[Pharmacological Action] OR ‘‘hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A

reductase inhibitor’’’[tiab] OR ‘‘hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase

inhibitors’’ OR ‘‘statin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘statins’’[tiab] OR

‘‘atorvastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘bervastatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘cerivastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘crilvastatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘dalvastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘fluindostatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘fluvastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘glenvastatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘lovastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘pitavastatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘pravastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘rosuvastatin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘simvastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘tenivastatin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘compactin’’[tiab] OR

‘‘mevinolin’’[tiab] OR ‘‘mevinolinic acid’’[tiab] OR ‘‘monacolin J’’[ti] OR ‘‘nacolin

L’’[tiab]) AND (‘‘Prostatic Neoplasms’’[Mesh] OR

(‘‘prostate’’[tiab] OR ‘‘prostatic’’[tiab] OR

‘‘genitourinary’’[tiab]) AND (‘‘malignancy’’[tiab] OR ‘‘cancer’’[tiab] OR

‘‘adenocarcinoma’’[tiab] OR ‘‘carcinoma’’[tiab] OR

‘‘neoplasm’’[tiab]))

EMBASE search terms:

(‘hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase

inhibitor'/exp OR statin:ti OR statins:ti OR ‘hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A

reductase inhibitor’:ti OR ‘hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase

inhibitors’:ti OR atorvastatin:ti OR bervastatin:ti OR cerivastatin:ti OR

crilvastatin:ti OR dalvastatin:ti OR fluindostatin:ti OR fluvastatin:ti OR

glenvastatin:ti OR lovastatin:ti OR mevastatin:ti OR pitavastatin:ti OR

pravastatin:ti OR rosuvastatin:ti OR simvastatin:ti OR tenivastatin:ti OR

advicor:ti OR altocor:ti OR altoprev:ti OR baycol:ti OR caduet:ti OR

compactin:ti OR crestor:ti OR lescol:ti OR lipex:ti OR lipitor:ti OR lipobay:ti

OR lipostat:ti OR livalo:ti OR mevacor:ti OR mevinolin:ti OR ‘mevinolinic

acid':ti OR ‘monacolin J’:ti OR ‘nacolin L’:ti OR pitava:ti OR pravachol:ti OR

selektine:ti OR simcor:ti OR torvast:ti OR vytorin:ti OR zocor:ti) AND

(‘prostate tumor'/exp OR ((cancer:ti OR carcinoma:ti OR adenocarcinoma:ti OR

neoplasm:ti OR malignancy:ti) AND (prostate:ti OR prostatic:ti OR

genitourinary:ti))) AND [embase]/lim

references

- 1.Graaf MR, Richel DJ, van Noorden CJ, et al. Effects of statins and farnesyltransferase inhibitors on the development and progression of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(7):609–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton RJ, Freedland SJ. Review of recent evidence in support of a role for statins in the prevention of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18(3):333–339. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f9b3cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KK, Oza AM, Siu LL. The statins as anticancer agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(1):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann D, Reynolds K, Smith D, et al. Trends in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US adults: impact of the 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(9):1208–12015. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L181. doi:10.1345/aph.1L181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shannon J, Tewoderos S, Garzotto M, et al. Statins and prostate cancer risk: a case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(4):318–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi203. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flick ED, Habel LA, Chan KA, et al. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer in the California Men's Health Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(11):2218–2225. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0197. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Visvanathan K, et al. Statin drugs and risk of advanced prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(24):1819–1825. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj499. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs EJ, Rodriguez C, Bain EB, et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs and advanced prostate cancer incidence in a large US cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(11):2213–2217. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0448. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollmeier MA, Katz MS, Mak K, et al. Improved biochemical outcomes with statin use in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(3):713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Sitaras NM. Statin use and the risk of prostate cancer: a metaanalysis of 6 randomized clinical trials and 13 observational studies. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(4):899–904. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23550. doi:10.1002/ijc.23550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browning DR, Martin RM. Statins and risk of cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(4):833–843. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22366. doi:10.1002/ijc.22366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, et al. Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(1):74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.74. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts CG, Guallar E, Rodriguez A. Efficacy and safety of statin monotherapy in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):879–887. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.879. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.8.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein EA, Corsini A, Gimpelewicz CR, et al. Fluvastatin treatment is not associated with an increased incidence of cancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(9):1028–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01071.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor ML, Wells BJ, Smolak MJ. Statins and cancer: a meta-analysis of case–control studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17(3):259–268. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b721fe. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b721fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murtola TJ, Tammela TL, Lahtela J, et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs and prostate cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(11):2226–2232. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0599. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonkhoff H. Factors implicated in radiation therapy failure and radiosensitization of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:593241. doi: 10.1155/2012/593241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68(11):4447–4454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):435–448. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomella LG, Zeltser I, Valicenti RK. Use of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy to prevent or delay recurrence of prostate cancer in patients undergoing surgical treatment for prostate cancer. Urology. 2003;62(Suppl 1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.025. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilepich MV, Winter K, Lawton CA, et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma—long-term results of phase III RTOG 85–31. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1285–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.047. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyad MA, Merrick GS, Butler WM, et al. Statins, especially atorvastatin, may favorably influence clinical presentation and biochemical progression-free survival after brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;66(6):1150–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.053. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;8:101–129. doi:10.2307/3001666. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. doi:10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi:10.2307/2533446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. doi:10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcella SW, David A, Ohman-Strickland PA, et al. Statin use and fatal prostate cancer: a matched case–control study. Cancer. 2012;118(16):4046–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niraula S, Pond G, De Wit R, et al. Influence of concurrent medications on outcomes of men with prostate cancer included in the TAX 327 study. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton RJ, Banez LL, Aronson WJ, et al. Statin medication use and the risk of biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: results from the search database. J Urol. 2009;181(4):574. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(09)61620-7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritch C, Hruby G, Badani K, et al. Statin drugs, prostate specific antigen and biochemical outcome following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2010;183(4):e720–e721. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.1796. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton R, Vijai J, Gallagher D, et al. Analysis of statin medication, genetic variation and prostate cancer outcomes. J Urol. 2011;185(4):e401. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.1028. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shippy AM, Katz MS, Yamada Y, et al. Statin use and clinical outcomes: after high dose radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(3):S113. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.209. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz MS, Carroll PR, Cowan JE, et al. Association of statin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use with prostate cancer outcomes: results from CaPSURE. BJU Int. 2010;106(5):627–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09232.x. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavery H, Hobbs A, Ghanaat M, et al. Preoperative statin use associated with lower PSA but similar histopathologic outcomes. J Urol. 2011;185(4):e61. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma NK, Ruth K, Horwitz E, et al. Statin use prior to radiation therapy for prostate cancer does not improve outcome: the Fox Chase experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(3):S366. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.688. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alizadeh M, Sylvestre MP, Zilli T, et al. Effect of statins and anticoagulants on prostate cancer aggressiveness. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(4):1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.042. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton RJ, Banez LL, Aronson WJ, et al. Statin medication use and the risk of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) Database. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3389–3398. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25308. doi:10.1002/cncr.25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krane LS, Kaul SA, Stricker HJ, et al. Men presenting for radical prostatectomy on preoperative statin therapy have reduced serum prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2010;183(1):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.151. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rioja J, Pinochet R, Savage CJ, et al. Impact of statin use on pathologic features in men treated with radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2010;183(4):e51. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.176. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ku JH, Jeong CW, Park YH, et al. Relationship of statins to clinical presentation and biochemical outcomes after radical prostatectomy in Korean patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14(1):63–68. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.39. doi:10.1038/pcan.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mondul AM, Han M, Humphreys EB, et al. Association of statin use with pathological tumor characteristics and prostate cancer recurrence after surgery. J Urol. 2011;185(4):1268–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.089. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ritch CR, Hruby G, Badani KK, et al. Effect of statin use on biochemical outcome following radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011;108(8 B):E211–E216. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10159.x. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mass AY, Agalliu I, Laze J, et al. Preoperative statin therapy is not associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: our experience and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2012;188(3):786–91. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moyad MA, Merrick GS, Butler WM, et al. Statins, especially atorvastatin, may improve survival following brachytherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urol Nurs. 2006;26(4):298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soto DE, Daignault S, Sandler HM, et al. No effect of statins on biochemical outcomes after radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2009;73(1):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.055. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gutt R, Tonlaar N, Kunnavakkam R, et al. Statin use and risk of prostate cancer recurrence in men treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2653–2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3003. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oh DS, Song H, Freedland S, et al. Statin use and prostate cancer recurrence in men treated with brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):S12–S13. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.025. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaorsky NG, Buyyounouski MK, Li T, et al. Aspirin and statin nonuse associated with early biochemical failure after prostate radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(1):e13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salih T, Aziz K, Thiyagarajan S, et al. Radiosensitization of MYC-overexpressing prostate cancer cells by statins. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl 7) abstr 260. [Google Scholar]

- 56.He Z, Mangala LS, Theriot CA, et al. Cell killing and radiosensitizing effects of atorvastatin in PC3 prostate cancer cells. J Radiat Res. 2012;53(2):225–233. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11114. doi:10.1269/jrr.11114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen PL, Je Y, Schutz FA, et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with cardiovascular death in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2359–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1745. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caporaso NE. Statins and cancer-related mortality—let's work together. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1848–1850. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1210002. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1210002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D'Amico AV. Statin use and the risk of prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radiation therapy with or without hormone therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2651–2652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5809. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamilton RJ, Goldberg KC, Platz EA, et al. The influence of statin medications on prostate-specific antigen levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(21):1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn362. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldfine AB. Statins: is it really time to reassess benefits and risks? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1752–1755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1203020. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1203020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]