Abstract

Background

This was a post hoc analysis of patients with non-squamous histology from a phase III maintenance pemetrexed study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Patients and methods

The six symptom items' [average symptom burden index (ASBI)] mean at baseline was calculated using the lung cancer symptom scale (LCSS). Low and high symptom burden (LSB, ASBI < 25; HSB, ASBI ≥ 25) and performance status (PS: 0, 1) subgroups were analyzed for treatment effect on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) using the Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for demographic/clinical factors.

Results

Significantly longer PFS and OS for pemetrexed versus placebo occurred in LSB patients [PFS: median 5.1 versus 2.4 months, hazard ratio (HR) 0.49, P < 0.0001; OS: median 17.5 versus 11.0 months, HR 0.63, P = 0.0012] and PS 0 patients (PFS: median 5.5 versus 1.7 months, HR 0.36, P < 0.0001; OS: median 17.7 versus 10.3 months, HR 0.54, P = 0.0019). Significantly longer PFS, but not OS, occurred in HSB patients (median 3.7 versus 2.8 months, HR 0.50, P = 0.0033) and PS 1 patients (median 4.4 versus 2.8 months, HR 0.60, P = 0.0002).

Conclusions

ASBI and PS are associated with survival for non-squamous NSCLC patients, suggesting that maintenance pemetrexed is useful for LSB or PS 0 patients following induction.

Keywords: lung cancer symptom scale, maintenance therapy, non-squamous NSCLC, patient-reported symptoms, pemetrexed, survival

introduction

Administration of platinum-based chemotherapy in first-line non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has demonstrated modest improvements in overall survival (OS). However, many patients are unable to receive more than four to six cycles of therapy due to treatment-related toxic effects [1–6]. For patients without disease progression after first-line treatment, tolerable maintenance chemotherapy provides a therapeutic advancement in the treatment of NSCLC [7]. As a result, more patients are benefiting from additional cycles of therapy, with improved survival. Patients with advanced NSCLC who receive maintenance therapy tend to have a better overall prognosis than those who do not receive maintenance therapy, as they must have achieved a sufficient response or stable disease (SD) during induction therapy and have acceptable tolerability in order to receive maintenance therapy [8–12].

In the NSCLC setting, maintenance therapies that have resulted in statistically significant improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) or time to progression include gemcitabine, docetaxel, gefitinib, and erlotinib with bevacizumab [8, 13–18]. Maintenance pemetrexed has resulted in both improved PFS and OS versus placebo in patients with non-squamous NSCLC [19, 20]. As previously reported, this phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo following a non-pemetrexed doublet induction regimen showed that the 481 patients with non-squamous histology who received maintenance pemetrexed (n = 325) experienced significantly longer PFS and OS versus those who received placebo (n = 156): a median PFS of 4.5 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.2–5.6] versus 2.6 months [95% CI: 1.6–2.8; hazard ratio (HR) 0.44, 95% CI: 0.36–0.55, P < 0.0001] and a median OS of 15.5 months (95% CI: 13.2–18.1) versus 10.3 months (95% CI: 8.1–12.0; HR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.56–0.88, P = 0.002) [19]. Additionally, maintenance pemetrexed was well tolerated [19]. Only one other maintenance therapy, erlotinib, has resulted in statistically significant improvements in OS versus placebo [21].

Some clinicians advocate delaying chemotherapy after first-line treatment instead of administering maintenance therapy immediately post-induction for some patients, particularly those with few disease symptoms, better performance status (PS), or those who may be more likely to experience the risks of chemotherapy as opposed to the benefits [4, 22–25]. Clinical trials to date have not been designed to answer the question as to which patients will derive the greatest benefit from maintenance chemotherapy versus waiting to receive therapy until disease progression (i.e. ‘chemotherapy holiday’). The Kaplan–Meier figures of PFS in both of the pemetrexed maintenance trials and the erlotinib maintenance trial demonstrate that ∼25% of patients had progressed or died at the first 6-week evaluation of maintenance therapy [19–21], further reinforcing the need to identify factors that predict which patients may benefit from maintenance therapy.

PS and symptom burden are potential factors that are increasingly recognized for their added utility in clinical decision-making in cancer. PS is a useful clinical measure that appears to significantly influence survival and determine treatment [26]. Additionally, the prognostic value of patient-reported symptoms has been documented previously [27–31]. Recently, a post hoc analysis of patient-reported symptoms was conducted on a phase III trial of pemetrexed and cisplatin in mesothelioma [32, 33]. In the univariate analysis, significant prognostic effects on OS were observed for multiple baseline lung cancer symptom scale (LCSS) items; in the multivariate analysis (adjusted for demographic/clinical variables including PS), the average symptom burden index (ASBI, the mean of LCSS symptom items) was prognostic, with patients with low symptom burden (LSB; ASBI < 25) having longer OS than those with high symptom burden (HSB; ASBI ≥ 25) [33].

Given these findings and the lack of clinical trials designed to identify factors associated with the benefit of maintenance therapy, we conducted a post hoc analysis of existing clinical trial data [19]. Specifically, we assessed the association of baseline patient-reported symptom burden and PS with maintenance pemetrexed efficacy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study of advanced NSCLC [19]. First, we examined the patients' demographic and clinical characteristics by baseline patient symptom burden, measured by the LCSS, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS. Then, we examined the treatment effect of pemetrexed versus placebo on PFS and OS by baseline symptom burden and PS.

patients and methods

patients and treatment

Ciuleanu et al. [19] published results from a global phase III study that evaluated maintenance pemetrexed in patients with stage IIIB/IV NSCLC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00102804). Patients with a baseline ECOG PS of 0 or 1 received four cycles of one of the following doublet regimens as induction chemotherapy: gemcitabine–carboplatin, gemcitabine–cisplatin, paclitaxel–carboplatin, paclitaxel–cisplatin, docetaxel–carboplatin, or docetaxel–cisplatin. Patients who achieved a partial response (PR), complete response (CR), or SD were then randomized (2:1) to receive maintenance pemetrexed (500 mg/m2, day 1) plus best supportive care (n = 441) or placebo plus best supportive care (n = 222) in 21-day cycles until disease progression. All patients received vitamin B12, folic acid, and dexamethasone [19].

The study on which this analysis was done was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines, and all patients provided written informed consent before treatment.

In this post hoc analysis, we included data from 481 patients with non-squamous histology. Histology has been shown to be predictive of efficacy with pemetrexed in advanced NSCLC, and non-squamous is currently the population indicated by the United States Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency in this setting [34–36].

assessments

The primary end point of PFS was measured from the date of randomization to the first date of progressive disease or death from any cause [19]. OS was measured from the date of randomization to the date of death from any cause [19].

Patient-reported symptoms were measured using the patient scale LCSS, a reliable and valid lung cancer-specific instrument [37]. The patient scale LCSS questionnaire consists of nine items, each scored with a 100-mm visual analog scale used to evaluate six symptoms associated with lung cancer (loss of appetite, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, pain, and hemoptysis) as well as three global items used to evaluate the interference with normal activities, distress from lung cancer symptoms, and overall quality of life (QoL) [37]. Each item is scored from 0 (none) to 100 (worst). For this analysis, the mean of the six symptom items at baseline was calculated to provide an ASBI. Symptom subgroups were defined by ASBI as LSB (ASBI < 25) and HSB (ASBI ≥ 25). Twenty-five was chosen as the cut point to align with the ‘mild’ category of the LCSS observer scale. The observer scale contains the previously mentioned six symptoms, which are rated using 5-point categorical scales (none, mild, moderate, marked, and severe).

statistical analyses

Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics within each symptom burden and ECOG PS subgroup and compared between symptom burden subgroups and ECOG PS subgroups. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables between subgroups.

Two-sample t-tests were used to compare the mean scores of LCSS items in the ECOG PS 0 subgroup with those in the ECOG PS 1 subgroup.

OS and PFS HRs and 95% CIs comparing pemetrexed with placebo were estimated for all patients and for each subgroup using the Cox proportional hazard models with treatment effect as the only covariate. Forest plots of these HRs and CIs were generated to investigate treatment heterogeneity.

Subgroup analyses for ASBI and ECOG PS on PFS and OS were carried out using the Cox proportional hazard models with treatment, ASBI or PS subgroup, the interaction effect between treatment and subgroup, and demographic/clinical factors as covariates. The interaction effect was designated significant at the level of 0.2 (i.e. P < 0.2). Because this was a post hoc analysis that may not have enough power to detect the interaction effect, a raised significance level of 0.2 for interaction effect was used [38]. The Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the maintenance treatment effect within each subgroup (significance level 0.05), adjusting for demographic/clinical factors.

For the PS subgroup analysis, eight demographic/clinical factors [19] were included in the models: age (<65 versus ≥65 years), gender (female versus male), race (Caucasian versus other), smoking status (no versus yes), stage (IIIB versus IV), previously treated brain metastases (yes versus no), platinum component of induction chemotherapy (cisplatin versus carboplatin), and best tumor response to induction chemotherapy (CR/PR versus SD). For the ASBI subgroup analysis, PS (0 versus 1) was included in the model to determine whether ASBI has additional predictive value after controlling for it and the other eight demographic/clinical factors. We also explored the sensitivity of results to the cut-point definition by conducting analyses with ASBI values of 20 and 30.

results

baseline patient characteristics and LCSS

Of the 481 patients with non-squamous histology, 464 patients [314 (96.6%) on pemetrexed, 150 (96.2%) on placebo] provided ASBI data at baseline. For these patients, the median baseline ASBI was 15 and the mean was 18. There were 62.5%, 71.8%, and 83.6% of patients with an ASBI less than 20, 25, and 30, respectively. The 17 patients who were missing baseline LCSS assessments were excluded from the ASBI subgroup analyses. Additionally, two patients with missing baseline ECOG PS were excluded from the PS subgroup analyses.

Table 1 shows the baseline patient and disease characteristics for patients with non-squamous NSCLC by ASBI (LSB and HSB) and PS subgroups. The mean age was 59 years for patients with LSB and a PS of 0 and 61 years for patients with HSB and a PS of 1. As expected, there were significantly more patients with good PS of 0 in the LSB group (ASBI < 25) than in the HSB group (ASBI ≥ 25). Significantly more patients with HSB were aged ≥65 years and had stage IV disease, whereas fewer patients with HSB had a CR/PR response to induction. Similarly, significantly more patients with PS 1 were aged ≥65 years. More patients with PS 0 had CR/PR responses to induction and received cisplatin as part of induction therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics by ASBI and PS subgroups

| LSB (ASBI < 25) (n = 333)a | HSB (ASBI ≥ 25) (n = 131)a | P-valueb | PS = 0 (n = 193)a | PS = 1 (n = 286)a | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged ≥ 65 years [n (%)] | 98 (29.4) | 53 (40.5) | 0.0225 | 51 (26.4) | 107 (37.4) | 0.0121 |

| Male [n (%)] | 224 (67.3) | 95 (72.5) | 0.2719 | 134 (69.4) | 196 (68.5) | 0.8349 |

| ECOG PS 0 [n (%)] | 144 (43.4) | 40 (30.5) | 0.0110 | — | — | — |

| Stage IV [n (%)] | 268 (80.5) | 116 (89.2) | 0.0245 | 155 (80.7) | 239 (83.6) | 0.4243 |

| Platinum component of induction therapy (cisplatin) [n (%)] | 147 (44.1) | 52 (40.0) | 0.4183 | 95 (49.5) | 111 (38.8) | 0.0209 |

| Best tumor response to induction chemotherapy (CR/PR) [n (%)] | 169 (50.8) | 50 (38.8) | 0.0206 | 106 (55.5) | 118 (41.4) | 0.0025 |

| Ethnic origin (Caucasian) [n (%)] | 187 (56.2) | 91 (69.5) | 0.0085 | 127 (65.8) | 164 (57.3) | 0.0629 |

| Smoking status (non-smoking) [n (%)] | 104 (31.6) | 37 (28.2) | 0.4797 | 56 (29.2) | 89 (31.4) | 0.5961 |

| Previously treated brain metastases (yes) [n (%)] | 305 (91.6) | 118 (90.1) | 0.6047 | 180 (93.3) | 257 (89.9) | 0.1964 |

aOf the 481 non-squamous patients, 17 were missing LCSS assessments and two were missing ECOG PS.

bChi-square test. Bold P-values are significant.

ASBI, average symptom burden index; PS, performance status; LSB, low symptom burden; HSB, high symptom burden; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CR, complete response; PR, partial response. The denominator for the percentage is the number of patients with baseline data for each variable in each subgroup.

Table 2 shows the baseline LCSS by PS subgroups. PS 0 patients had significantly lower mean LCSS scores than PS 1 patients for fatigue, pain, and ASBI as well as all three global items (i.e. activity level, symptom distress, and QoL; all P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Association between mean LCSS scores and PS

| LCSS item | PS = 0 (n = 193)a | PS = 1 (n = 286)a | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of appetite | 21.1 | 23.4 | 0.2884 |

| Fatigue | 27.4 | 35.1 | 0.0019 |

| Cough | 15.4 | 18.2 | 0.1776 |

| Dyspnea | 18.0 | 19.7 | 0.4477 |

| Pain | 11.3 | 17.1 | 0.0065 |

| Hemoptysis | 1.7 | 2.5 | 0.2186 |

| Interference with activity level | 25.1 | 36.5 | <0.0001 |

| Symptom distress | 16.0 | 22.9 | 0.0018 |

| Global QoL | 26.4 | 37.0 | <0.0001 |

| ASBIc | 15.9 | 19.4 | 0.0053 |

aOf the 481 non-squamous patients, two were missing ECOG PS.

bTwo-sample t-test. Bold P-values are significant.

cASBI = mean of six LCSS items: loss of appetite, fatigue, cough, dyspnea, pain, and hemoptysis.

LCSS, lung cancer symptom scale; PS, performance status; QoL, quality of life; ASBI, average symptom burden index.

treatment heterogeneity

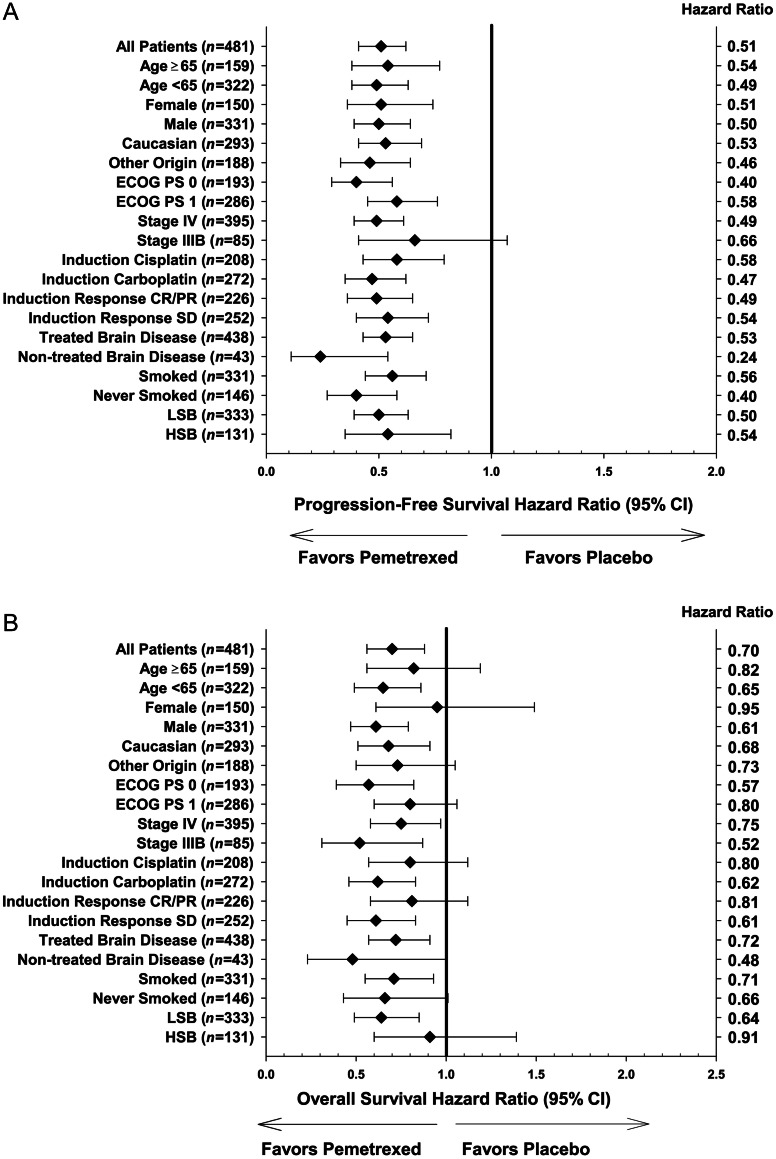

The forest plot (Figure 1A) shows that pemetrexed significantly improved PFS, compared with placebo, in all subgroups except stage IIIB disease, including both the ASBI and ECOG PS subgroups. Pemetrexed significantly improved OS compared with placebo in patients with ECOG PS 0 (HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.39–0.82, P = 0.0027) and LSB (HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.49–0.85, P = 0.0019), in addition to other demographic/clinical subgroups with the upper limit of 95% CI <1 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

PFS (A) and OS (B) HR (pemetrexed versus placebo) by clinical and demographic subgroups for patients with non-squamous histology (n = 481). n, number of patients in each subgroup; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; LSB, low symptom burden; HSB, high symptom burden.

treatment effect by ASBI subgroups

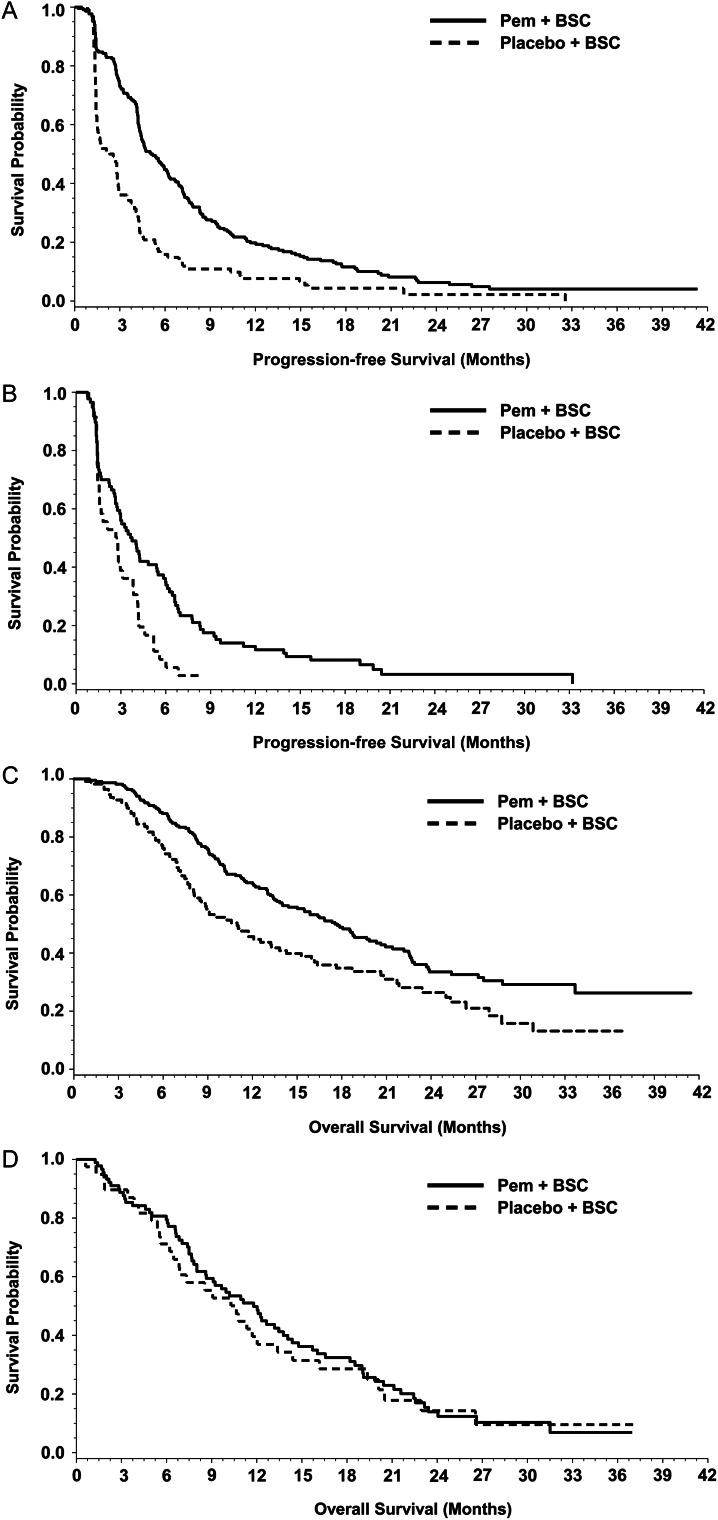

Figure 2A and B shows the Kaplan–Meier curves by treatment (pemetrexed versus placebo) within ASBI subgroups for PFS. As shown in Table 3, there was no significant interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroups on PFS. Pemetrexed significantly improved PFS versus placebo for patients with LSB (median 5.1 versus 2.4 months, HR 0.49, P < 0.0001) and HSB (median 3.7 versus 2.8 months, HR 0.50, P = 0.0033).

Figure 2.

Treatment effect: PFS for non-squamous patients with LSB (A) and HSB (B) (n = 464); OS for non-squamous patients with LSB (C) and HSB (D) (n = 464). Pem, pemetrexed; BSC, best supportive care. Seventeen patients were excluded who were missing baseline LCSS assessments.

Table 3.

Association of pemetrexed treatment and efficacy by ASBI and PS subgroups

| LSB (ASBI < 25) |

HSB (ASBI ≥ 25) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pemetrexed + BSC (N = 222)a | Placebo + BSC (N = 111)a | Pemetrexed + BSC (N = 92)a | Placebo + BSC (N = 39)a | |

| PFS (95% CI, months) | ||||

| Median | 5.1 (4.4, 6.2) | 2.4 (1.5, 2.9) | 3.7 (2.8, 5.4) | 2.8 (1.5, 3.8) |

| HR (pemetrexed versus placebo) | 0.50 (0.39, 0.63), P < 0.0001 | 0.54 (0.35, 0.82), P = 0.0036 | ||

| Adjusted HR (pemetrexed versus placebo)b | 0.49 (0.38, 0.62), P < 0.0001 | 0.50 (0.32, 0.80), P = 0.0033 | ||

| Interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroup | P = 0.6699 | |||

| OS (95% CI, months) | ||||

| Median | 17.5 (14.0, 20.6) | 11.0 (8.1, 14.3) | 11.8 (8.6, 14.1) | 10.6 (6.8, 13.4) |

| HR (pemetrexed versus placebo) | 0.64 (0.49, 0.85), P = 0.0019 | 0.91 (0.60, 1.39), P = 0.6729 | ||

| Adjusted HR (pemetrexed versus placebo)b | 0.63 (0.47, 0.83), P = 0.0012 | 1.02 (0.65, 1.60), P = 0.9188 | ||

| Interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroup | P = 0.1499 | |||

| PS 0 (n = 133)a | PS 0 (n = 60)a | PS 1 (n = 190)a | PS 1 (n = 96)a | |

| PFS (95% CI, months) | ||||

| Median | 5.5 (4.1, 6.9) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.9) | 4.4 (4.2, 5.4) | 2.8 (1.7, 2.9) |

| HR (pemetrexed versus placebo) | 0.40 (0.29, 0.56), P < 0.0001 | 0.58 (0.45, 0.76), P < 0.0001 | ||

| Adjusted HR (pemetrexed versus placebo)c | 0.36 (0.25, 0.52), P < 0.0001 | 0.60 (0.45, 0.78), P = 0.0002 | ||

| Interaction effect between treatment and PS subgroup | P = 0.0900 | |||

| OS (95% CI, months) | ||||

| Median | 17.7 (12.5, 22.4) | 10.3 (8.5, 14.4) | 14.1 (12.1, 17.3) | 10.6 (7.0, 13.2) |

| HR (pemetrexed versus placebo) | 0.57 (0.39, 0.82), P = 0.0027 | 0.80 (0.60, 1.06), P = 0.1200 | ||

| Adjusted HR (pemetrexed versus placebo)c | 0.54 (0.37, 0.80), P = 0.0019 | 0.78 (0.58, 1.05), P = 0.1045 | ||

| Interaction effect between treatment and PS subgroup | P = 0.2154 | |||

Bold P-values are significant. Treatment effect within each subgroup was significant at P < 0.05; the interaction effect between treatment and subgroup was significant at P < 0.2.

aOf the 481 non-squamous patients, 17 were missing LCSS assessments and two were missing ECOG PS.

bAdjusted for age group (aged <65 versus ≥65 years), gender (female versus male), race (Caucasian versus other), smoking status (no versus yes), stage (IIIB versus IV), previously treated brain metastases (yes versus no), platinum component of induction (cisplatin versus carboplatin), best response to prior chemotherapy (CR/PR versus SD), and ECOG performance status (0 versus 1).

cAdjusted for age group (aged <65 versus ≥65 years), gender (female versus male), race (Caucasian versus other), smoking status (no versus yes), stage (IIIB versus IV), previously treated brain metastases (yes versus no), platinum component of induction (cisplatin versus carboplatin), and best response to prior chemotherapy (CR/PR versus SD).

ASBI, average symptom burden index; PS, performance status; BSC, best supportive care; LSB, low symptom burden; HSB, high symptom burden; PFS, progression-free survival; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Figure 2C and D shows the Kaplan–Meier curves by treatment (pemetrexed versus placebo) within ASBI subgroups for OS. As shown in Table 3, the interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroups on OS was significant (P = 0.1499). For patients with LSB, pemetrexed significantly improved OS (median 17.5 versus 11.0 months, HR 0.63, P = 0.0012), whereas no significant treatment effect (pemetrexed versus placebo) for OS was observed for patients with HSB (median 11.8 versus 10.6 months, HR 1.02, P = 0.9188).

Sensitivity analyses were carried out using 20 (n = 290 with LSB < 20) and 30 (n = 388 with LSB < 30) as the ASBI cut points. The interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroups on PFS was not significant. Similar to the primary ASBI analysis, pemetrexed significantly improved PFS for patients with LSB and HSB (LSB P < 0.0001 for both the 20 and 30 cut points; HSB P = 0.0012 and P = 0.0257 for the 20 and 30 cut points, respectively). The interaction effect between treatment and ASBI subgroups on OS was significant (P = 0.1396 using the 20 cut point; P = 0.0582 using the 30 cut point). Similar to the primary ASBI analysis, pemetrexed significantly improved OS for patients with LSB (P = 0.0019 using the 20 cut point; P = 0.0009 using the 30 cut point) but showed no significant difference from placebo for patients with HSB.

treatment effect by PS subgroups

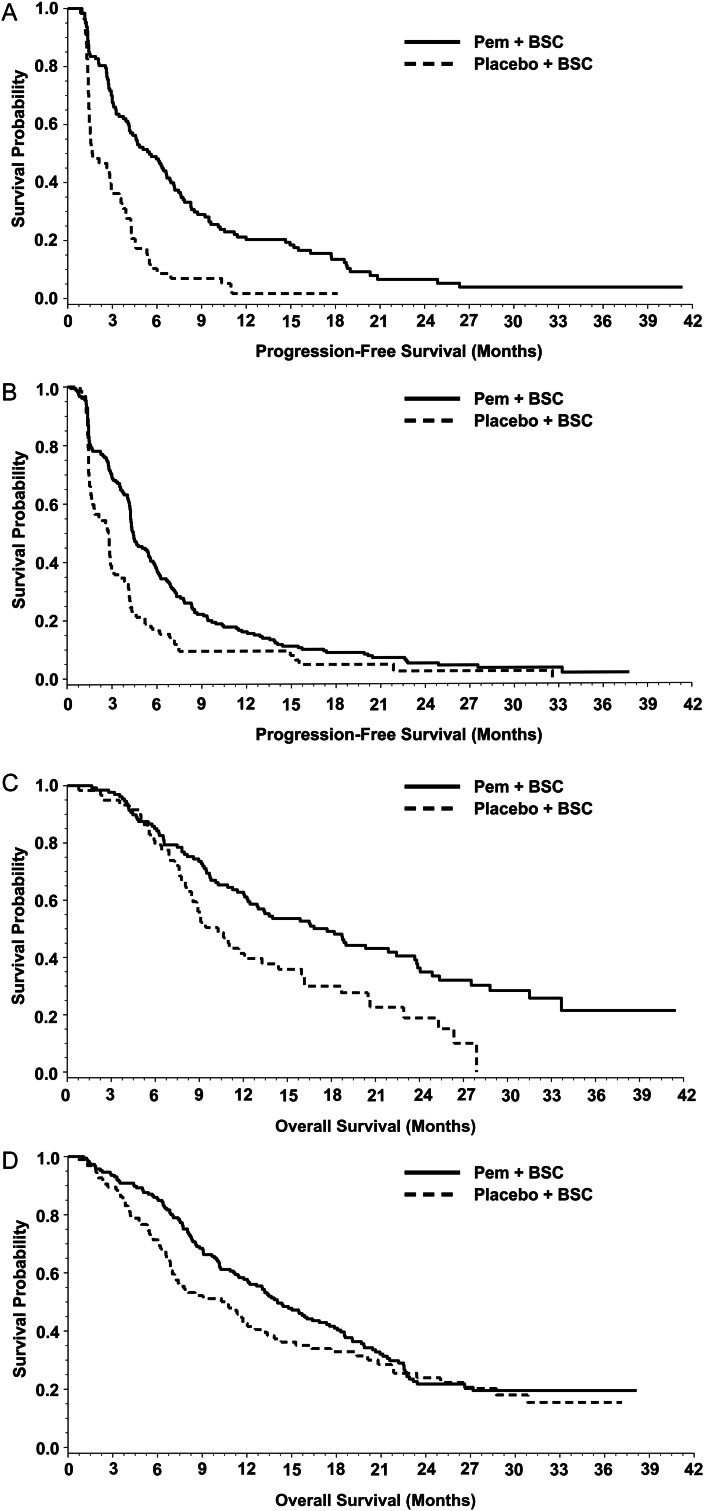

Figure 3A and B shows the Kaplan–Meier curves by treatment (pemetrexed versus placebo) within ECOG PS subgroups for PFS. As shown in Table 3, the interaction effect between treatment and ECOG PS subgroups on PFS was significant (P = 0.0900). Pemetrexed significantly improved PFS versus placebo in both ECOG PS 0 (median 5.5 versus 1.7 months, HR 0.36, P < 0.0001) and ECOG PS 1 patients (median 4.4 versus 2.8 months, HR 0.60, P = 0.0002).

Figure 3.

Treatment effect: PFS for non-squamous patients with PS 0 (A) and 1 (B) (n = 479); OS for non-squamous patients with PS 0 (C) and 1 (D) (n = 479). Pem, pemetrexed; BSC, best supportive care. Two patients were excluded who were missing baseline ECOG PS.

Figure 3C and D shows the Kaplan–Meier curves by treatment (pemetrexed versus placebo) within ECOG PS subgroups for OS. As shown in Table 3, the interaction effect between treatment and ECOG PS subgroup on OS was not significant. Patients receiving pemetrexed versus placebo had significantly longer median OS with ECOG PS 0 (median 17.7 versus 10.3 months, HR 0.54, P = 0.0019), but the difference for ECOG PS 1 was not significant (median 14.1 versus 10.6 months, HR 0.78, P = 0.1045).

discussion

In this post hoc analysis of a phase III study [19], the ASBI was an independent predictor of differential response to maintenance pemetrexed in patients with non-squamous NSCLC. Patients with LSB (ASBI < 25) experienced significantly improved PFS and OS when treated with maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo. Patients with HSB (ASBI ≥ 25) experienced significantly improved PFS but not OS. Both PFS and OS results were confirmed in sensitivity analyses using 20 and 30 as the ASBI cut points. Additionally, patients with ECOG PS 0 also experienced significantly improved PFS and OS, and patients with ECOG PS 1 experienced improved PFS with pemetrexed maintenance therapy versus placebo.

Debate continues regarding the benefit of immediate maintenance therapy versus delayed second-line treatment [39]. However, few studies have directly compared the benefit of maintenance versus delayed second-line treatment. Fidias et al. [8] observed statistically significantly longer PFS for immediate versus delayed docetaxel. Additionally, there was no significant difference in overall ASBI results between docetaxel treatment arms. In the delayed docetaxel arm, many of the patients who discontinued before treatment due to progressive disease had significant symptom deterioration that prevented the administration of therapy [8]. In a trial by Perol et al. [40], maintenance therapy with gemcitabine or erlotinib significantly improved PFS versus observation, with all patients receiving predefined second-line pemetrexed. The PFS HR of 0.55 in the gemcitabine maintenance arm was similar to that reported for all pemetrexed patients in our study (HR 0.50) [19].

Debate also continues regarding the appropriate selection of candidates for maintenance treatment [39]. In routine clinical practice, patients with high tumor burden and symptomatic disease may be candidates for maintenance (immediate) therapy, whereas asymptomatic patients are often given a ‘drug holiday’ after achieving maximum response, followed by second-line (delayed) treatment after progression [22–25]. However, by delaying treatment, patients risk symptomatic deterioration, including compromised PS, that could have an impact on their ability to receive subsequent therapy [8,10]. In both pemetrexed maintenance trials and the erlotinib maintenance trial [19–21], ∼25% of patients had progressed or died at the first scheduled tumor evaluation. As shown in the current study, ideal candidates for maintenance may be potentially identified by symptom burden or ECOG PS. Although asymptomatic patients (i.e. LSB) are often given a drug holiday, results from our study show that LSB as well as HSB patients do benefit from maintenance treatment. If validated prospectively, these results could be used to help predict which patients should receive maintenance treatment.

Several limitations are associated with this study. This was a post hoc analysis and more robust conclusions could have been drawn from prespecified and appropriately powered analyses. Given that this study focused on cytotoxic therapy with pemetrexed, additional research is warranted to evaluate the impact of targeted or other maintenance therapies. Additionally, this is a low symptom group of enrollees (with relatively low symptom scores at baseline and a mean ASBI of 18), limiting the variability in the data and the ability of the analyses to show treatment heterogeneity in subgroups defined by LCSS items and composite scores. Finally, although most patients in the placebo arm (not receiving active maintenance therapy) did not receive pemetrexed at the time of progressive disease, 18% did receive post-study pemetrexed, a number too small for further analysis; however, the selection of other agents was generally well balanced between treatment arms [19].

conclusions

The LCSS ASBI and PS provide an incremental value for clinical decision-making in addition to other disease and clinical characteristics that can help to identify non-squamous NSCLC patients who may benefit differentially from pemetrexed maintenance therapy. Baseline symptom burden (LSB or HSB) and ECOG PS (0 or 1) of non-squamous patients have an impact on the treatment effect on PFS and OS of maintenance chemotherapy with pemetrexed versus placebo. These data suggest that pemetrexed maintenance therapy is a useful treatment strategy for non-squamous NSCLC patients, especially those with LSB (minimal or no symptoms) or patients with PS 0 at successful completion of induction therapy. Prespecified analyses evaluating patient-reported symptoms as predictive factors are warranted to further test the validity of these results.

funding

This study was sponsored and funded by Eli Lilly and Company (no grant number).

disclosure

CO, LB, PW, WS, KBW, ENS, MEB, and WJ are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. TB declares no relevant financial conflicts of interest. CPB is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company and has been paid honorarium to serve on committees.

acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Noelle Gasco, of Eli Lilly and Company, for writing assistance and Patrick Peterson, of Eli Lilly and Company, and Jiaying Guo, of PharmaNet/i3, for statistical support.

references

- 1.Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Recent clinical trials using cisplatin, carboplatin and their combination chemotherapy drugs (review) Oncol Rep. 2004;11:559–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Non-small cell lung cancer Version 3.2012. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#nscl. (14 August 2012, date last accessed)

- 5.Wakelee H, Belani CP. Optimizing first-line treatment options for patients with advanced NSCLC. Oncologist. 2005;10(Suppl 3):1–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azzoli CG, Baker S, Termin S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6251–6266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gridelli C, Maione P, Rossi A, et al. Potential treatment options after first-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC: maintenance treatment or early second-line? Oncologist. 2009;14:137–147. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidias PM, Dakhil SR, Lyss AP, et al. Phase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:591–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérol M. Maintenance therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer–review of rationale, clinical need and available data. Eur Respir Dis. 2010;6:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, Belani CP. Maintenance therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: current status, controversies, and emerging consensus. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2496–2504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennell NA. Selection of chemotherapy for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79(electronic Suppl 1):eS46–eS50. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78.s2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarhini AA, Argiris A. Maintenance therapy for advanced-non small cell lung cancer. Open Lung Cancer J. 2010;3:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belani CP, Barstis J, Perry MC, et al. Multicenter, randomized trial for stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer using weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by maintenance weekly paclitaxel or observation. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2933–2939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, et al. Central European Cooperative Oncology Group CECOG. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westeel V, Quoix E, Moro-Sibilot D, et al. French Thoracic Oncology Collaborative Group (GCOT) Randomized study of maintenance vinorelbine in responders with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:499–506. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeda K, Hida T, Sato T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of platinum-doublet chemotherapy followed by gefitinib compared with continued platinum-doublet chemotherapy in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a west Japan thoracic oncology group trial (WJTOG0203) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:753–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mok TS, Wu YL, Yu CJ, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study of sequential erlotinib and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5080–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller VA, O'Connor P, Soh C, et al. for the ATLAS Investigators. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIIb trial (ATLAS) comparing bevacizumab (B) therapy with or without erlotinib (E) after completion of chemotherapy with B for first-line treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):abstr LBA8002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374:1432–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paz-Ares L, de Marinis F, Dediu M, et al. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival (OS) results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed (pem) plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo (plb) plus BSC immediately following induction treatment with pem plus cisplatin (cis) for advanced nonsquamous (NS) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl):abstr LBA7507. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. SATURN Investigators. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Addario G, Felip E ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):68–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzoli CG, Temin S, Giaccone G. 2011 Focused update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:63–66. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fidias P, Novello S. Strategies for prolonged therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5116–5123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stinchcombe TE, Socinski MA. Treatment paradigms for advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer in the era of multiple lines of therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:243–250. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819516a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Socinski MA, Morris DE, Masters GA, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. Chemotherapeutic management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):226S–243S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.226s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, et al. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1355–1363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, et al. EORTC Clinical Groups. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:865–871. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauser CA, Stockler MR, Tattersall MH. Prognostic factors in patients with recently diagnosed incurable cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osoba D. Lessons learned from measuring health-related quality of life in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:608–616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sprangers MA. Quality-of-life assessment in oncology. Achievements and challenges. Acta Oncol. 2002;41:229–237. doi: 10.1080/02841860260088764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang P, Bowman L, Shen W, et al. The lung cancer symptom scale (LCSS) as a prognostic indicator of overall survival in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) patients: post hoc analysis of a phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl):abstr 7075. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two Phase III studies. Oncologist. 2009;14:253–263. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Kris MG. An overview of the lung cancer symptom scale. In: Gralla RJ, Moinpour CM, editors. Assessing Quality of Life in Patients with Lung Cancer: A Guide for Clinicians. New York, NY: NCM Publishers; 1995. pp. 57–63. (Monograph, Quality of Life Symposium, 7th World Conference on Lung Cancer, Colorado Springs, Colorado, June1994) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selvin S. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiologic Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edelman MJ, Le Chevalier T, Soria JC. Maintenance therapy and advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: a skeptic's view. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1331–1336. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182629e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perol M, Chouaid C, Milleron BJ, et al. Maintenance with either gemcitabine or erlotinib versus observation with predefined second-line treatment after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC: IFCT-GFPC 0502 phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl):abstr 7507. [Google Scholar]