Abstract

Here in, we investigated the mechanism underlying overexpression of miR-135b in the human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell lines and in the HNSCC mouse model. Exogenous expression of miR-135b in these cell lines increased cell proliferation, migration, and colony formation. Gene silencing analysis revealed that miR-135b affects a regulator that inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). Increased miR-135b expression was positively correlated with HIF-1α expression and microvessel density in the HNSCC model. Thus, our data demonstrate that miR-135b acts as a tumor promoter by promoting cancer cell proliferation, colony formation, survival, and angiogenesis through activation of HIF-1α in HNSCC.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Mouse model, MicroRNA, Hypoxia

1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common cancer, with more than 450,000 newly diagnosed cases worldwide every year [1]. HNSCC progression involves the sequential acquisition of genetic and epigenetic alterations in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes [2]. Among them, the most frequent alterations include loss of heterozygosity or inactivating mutations in the Pten [3,4]. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling pathways play dual roles in head and neck cancer [5]. TGF-β serves as a tumor suppressor in early tumorigenesis, and as a tumor promoter in the late stages of tumorigenesis [5]. The acidity level and hypoxia are reportedly very high in HNSCC, causing low response to chemotherapy. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) plays a key role in tumor hypoxia and correlates with shorter disease-free survival by upregulating antiapoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and angiogenic factor VEGFA [6]. Genetically engineered mouse models are powerful tools for investigating specific cause-and-effect relationships between molecular changes and cancer development and progression [7]. In the conditional Tgfbr2−/− mice [8] Tgfbr1−/− mice [9], progression to SCC was achieved only by using chemical carcinogens that promote Ras mutations. We have recently generated inducible Tgfbr1 and Pten compound conditional knockout (Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO) mice with head and neck epithelium that undergoes fast tumor formation and full penetration [10,11] Molecular analysis showed that these HNSCC tumors exhibit multiple pathological alterations similar to those commonly found in human HNSCCs. These alterations include overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and increased phosphorylation of Akt, as well as activation of the nuclear factor-κB and the signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (Stat3) pathways [10,11].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs that regulate the translation and degradation of target mRNAs [12,13]. Accumulating evidence indicates that miRNA may act as an oncogene or tumor suppressor, impacting cancer initiation and progression [14–16]. The abundance of miRNAs, and their apparent pluripotent actions, suggests that the identification of miRNAs involved in oncogenesis may yield novel targets or signaling pathways that suitable for therapeutic intervention [16–20]. Studies profiling miRNA expression revealed that a panel of miRNAs participating in human HNSCC and miRNA expression, such as miR-21 and miR-205, can be used as specific markers of HNSCCs [21–23]. miR-31 is another important oncogenic miRNA that contributes to the development of HNSCC by impeding factor-inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor (FIH) expression, thus resulting in activation of HIF [24]. miR-135b has been previously associated with human colorectal cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and gliomas [25–28]. miR-135b contributes to colorectal cancer pathogenesis by regulating adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene expression and the Wnt pathway activity [29,30], and its expression levels correlate with the estrogen receptor status in breast cancer [26]. Microarray profiling of human HNSCC samples showed that miR-135b was one of the most significantly upregulated miRNAs [24]. However, the precise functions of miR-135b in many cancers, including HNSCC, are still unknown.

In the present study, we have identified miR-135b as one of the most markedly upregulated miRNAs in Tgfbr1/Pten compound knockout mice that spontaneously develop HNSCC. We found that miR-135b promotes cancer cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration, and that it enhances the angiogenic activity of the human HNSCC cell line through regulation of FIH and HIF-1α expression. miR-135b expression was correlated with angiogenesis in vitro as well as in the HNSCC mice model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Generation of Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice

The Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice (K14-CreERtam; Tgfbr1flox/flox; Ptenflox/flox) were generated as previous described previously [10,11] by mating inducible Tgfbr1 conditional knockout mice (Tgfbr1 cKO, K14-CreERtam; Tgfbr1flox/flox) [9] with Ptenflox/flox mice. The Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice and their controls came from the same litter and therefore had the same mixed genetic background of C57BL/6; FVBN; CD1; 129. One dose of 50 mg DMBA for initiation of cancer in Tgfbr1 cKO mice was given 15 days after Tamoxifen gavage [9]. K14-CreERtam; Ptenflox/flox (Pten cKO) mice were maintained as previously described [10,11].

2.2. Cell culture and transfection

HNSCC cell lines CAL27, SSC4, SCC9, SCC15, and SCC25 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). HNSCC cell lines HSC3, KCCT873, KCCOR891, OSC19, and human oral keratinized cell (HOK) were kindly provided by Puri et al. [31]. Cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), at 5% CO2 and 37 °C in a humidified incubator with anti-vibration equipment. For the TGFBR1 and PTEN knockdown experiment, TGFBR1 siRNA, PTEN siRNA, or combined TGFBR1/PTEN siRNA were transfected into appropriate cells using HiPerfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) with a final concentration of 5nM. All-star negative controls (Qiagen), confirmed to have no interference with other miRNAs, were used as negative controls [11]. MAPK1 siRNA and Cell Death siRNA (Qiagen) were used as positive controls. For functional analysis, non-targeting miRNA negative controls (Exiqon, Woburn, MA), a specific locked nucleic acid (LNA) inhibitor for miR-135b (anti-miR-135b LNA) (Exiqon, Woburn, MA), and miR-135b mimics (Qiagen) were transfected into the appropriate cells using RNAifect transfection reagent (Qiagen) with a final concentration of 25 nM. For inhibition efficiency and target mRNA transcription studies, RNA was extracted 24 h after transfection. For protein extraction, cells were lysed 48 h after transfection. Primary endothelial cell line derived from human umbilical vein (HUVECs, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) was maintained in endothelial growth medium 2 (EGM-2, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) in gelatin-coated dishes, as described in the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Cell proliferation assay

To monitor cell proliferation and viability of the HNSCC cell line and endothelial cell line, CAL27, HSC3, and HUVEC cells (5000 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well microplate (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) in a final volume of 100 μL. After 12 h incubation, cells were transfected with negative control, miR-135b LNA, or miR-135b mimic vectors After 24 h, the transfection reagent was removed, and MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was performed according to the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. The percentage of cell growth was calculated based on 100% growth at 24 h after transfection.

2.4. Colony formation assay

To evaluate anchorage-dependent growth, CAL27 and HSC3 cells were seeded at a density of 400 cells per well in flat-bottomed six-well culture plates, and cultured until colonies were visible. The colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), as described [11]. The percentage of cells that formed into a clone was calculated [11].

2.5. “Scratch wound” migration assay

Cell migration was measured using a “scratch wound” assay, as described previously [32]. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary Material.

2.6. Transwell cell migration assay

The migration assay was performed using a Transwell chamber (Corning, Lowell, MA) containing a 6.5-mm diameter polycarbonate filter (pore size, 8 μm), as described previously [33]. Independent experiments were performed twice in quadruplicate. Membranes were cut, loaded in slices, and scanned by an Aperio CS scanner. Images were analyzed using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

2.7. Endothelial tube formation assay

Tube formation assays were performed as previously described [33]. Detailed procedures are described in the Supplementary material.

2.8. Western blot analysis

Cultured cells were lysed in T-PER (Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing a complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphate inhibitors (Roche, Branchburg, NJ). Tongue mucosa harvested from two individual Tgfbr1flox/flox/Ptenflox/flox mice and two Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice, and five tumors harvested from Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice, were used for Western blot analysis. Detailed procedures for immunoblotting were described in the Supplementary material as described previously [10,11].

2.9. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA, including miRNA from mouse tissue samples or HNSCC cell lines, was extracted using miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality control was performed as previously described. The miRNAs were subjected to quantitative 2-step real-time PCR. Kits for miScript Primer Assay (for miR-135b and U6), the miScript reverse transcription kit, and the miScript SYBR green PCR kit were purchased from Qiagen. MicroRNA-specific qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate on the Chrom 4 real-time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using a U6 probe as an internal control, according to the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. The primer used in this study was summarized in Supplementary Table 1. mRNA real-time PCR was performed using the Qiagen QuantiTect system as previously described [10,11].

2.10. Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

FIH, HIF-1α, and VEGFA were stained in the sections of Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue SCC samples with high miR-135b expression, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue SCC samples were stained with low miR-135b expression samples (n = 5). This was done by immunofluorescence, using previously reported protocols [9]. Immunofluorescence was observed by a Zeiss LSM 510 multiphoton confocal microscope and quantitated by Image J software. Immunohistochemical staining of CD31 (Abcam) was performed on frozen sections as previously described [10,11], using an appropriate biotin-conjugated secondary antibody and a Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Slices were scanned using an Aperio CS scanner, and microvessel density was quantified using Aperio microvessel density software (V9.0).

2.11. Statistical analysis

The difference between mRNA expression of controls and experimental samples, and the difference between the immunohistochemical quantifications of each group, were determined by the one-way ANOVA test followed by the Turkey or Dunnett post test, using the GraphPad Prism5 software package (GraphPad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA). Correlation of FIH, HIF-1α, and MVD staining with miR-135b expression levels was determined using the Pearson test with a two-tailed p value. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Asterisks denote statistical significance (ns, P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Spontaneous development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice

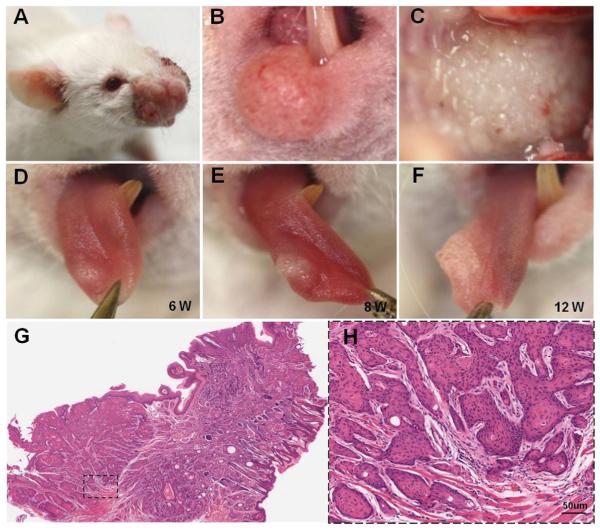

Four weeks after 5 daily oral applications of tamoxifen, hyperplasia was observed in areas of the head and neck region, such as the muzzle area (Fig. 1A), lips (Fig. 1B), and ears. Two weeks after the hyperplasia appeared, a tumor was observed in areas of the oral cavity, including the palate (Fig. 1C), tongue (Fig. 1D–F), oral floor, buccal mucosa, and gingiva. Histologically, all tumors were composed of atypical differentiated epithelial cells that grow as solid sheets or strands and occasionally as differentiated keratin pearls (Fig. 1G and H), which is a hallmark feature of squamous cell carcinoma.

Fig. 1.

Development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in tamoxifen-induced Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice. Tumors developed in the muzzle area (A), lips (B), and oral mucosa (C) of Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice. Progression of tongue cancer: tumor in dorsal tongue developed gradually from 6 weeks (D) to 8 weeks (E) and then to 12 weeks (F). The neoplasia affected the tip of the tongue and infiltrated deeply into the skeletal muscle layer (G and H). The tumor is composed of atypical cells that grow in solid sheets and occasionally differentiate into keratin pearls, a hallmark feature of squamous cell carcinomas (scale bar = 50 μm).

3.2. Upregulation of miR-135b in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

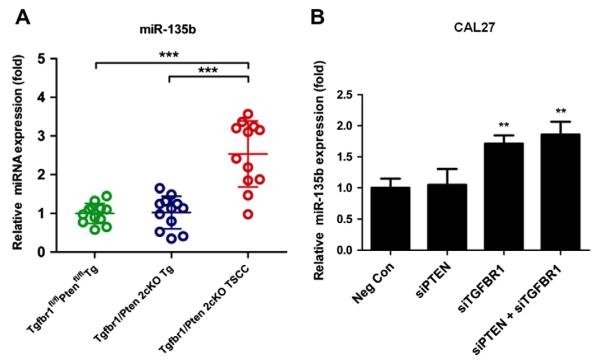

Using miRNA microarray profiling, we found that miR-135b was the most highly upregulated miRNA in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC as compared with Tgfbr1foxl/flox/Ptenflox/flox oral mucosa (data not shown). To further validate the expression levels of miR-135b, we performed quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) on these samples. As shown in Fig. 2A, miR-135b expression levels were 2.5-fold (P < 0.05) higher in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC, as compared to the Tgfbr1foxl/flox/Ptenflox/flox tongue. The significantly increased level of miR-135b in 2cKO HNSCC caught our attention, mainly because its role in HNSCC is largely unknown.

Fig. 2.

(A) Scatter dot plot of the mRNA expression of miR-135b in the Tgfbr1flox/flox Pten flox/flox tongue (Green), the Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue (blue), and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue SCC tissues. Horizontal lines, mean values. Mean ± SEM from triplicate analysis of four mice from each group. (B) Quantitative PCR of miR-135b 24 h after TGFBR1, PTEN, and combined TGFBR1/PTEN siRNA transfection. (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001, One-way ANOVA analysis with post-Turkey or Dunnett test).

3.3. miR-135b over-expression is related to Tgfbr1 deletion

To investigate whether the increase in miR-135b was related to deletion of TGFBR1 or PTEN, we knocked down TGFBR1 and/or PTEN in CAL27 cells using siRNA. To reduce the likelihood of RNAi off-target effects, we used two independent, non-overlapping siRNAs against TGFBR1 and PTEN siRNA. As shown by the RT-PCR results, the knocked down efficiency of each siRNA was more than 74% at 24 h following the transfection of siRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 1A). By 48 h after transfection, protein levels of TGFBR1 and PTEN were 9-fold lower than those of the negative controls (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that the miR-135b level was upregulated in CAL27 cells, wherein TGFBR1 or both TGFBR1 and PTEN were knocked down (Fig. 2B). This suggests that the increased expression of miR-135b correlates with the deletion of TGFBR1 in the human HNSCC cell line.

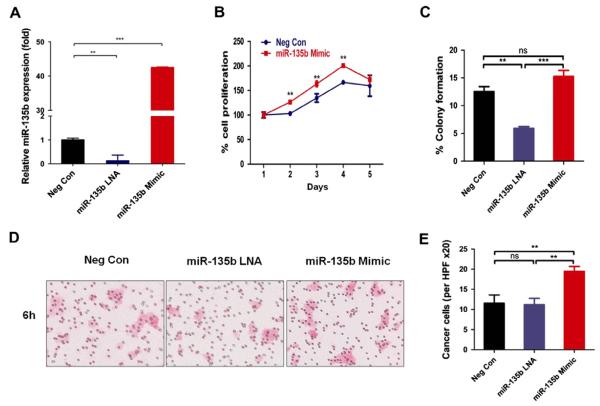

3.4. miR-135b increased the oncogenic potential of HNSCC cells

To investigate whether miR-135b plays a role in HNSCC development, we analyzed miR-135b expression in 7 human tongue cancer cell lines using RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 2). We found that SCC4 and metastatic HSC3 cell lines express miR-135b at much higher levels as compared with the human oral keratinocyte (HOK) cell line. CAL27, KCCT873, KCCOR891, and OSC19 maintain similar miR-135b expression levels compared to HOK. Therefore, we used the HSC3 cell line with high miR-135b expression and the CAL27 cell line with moderate miR-135b expression for the subsequent in vitro functional assays. We found that transfection with miR-135b locked nucleic acid inhibitor (LNA), but not the negative control, specifically knocked down miR-135b expression at 24 h (P < 0.01; Fig. 3A). However, transfection with the miR-135b mimic significantly upregulated miR-135b expression more than 40-fold, as compared to cells transfected with the negative control (P < 0.001; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

miR-135b Increased oncogenic potential of the CAL27 cell line. (A), miR-135b expression decreased with miR-135b LNA treatment for 24 h and exogenous miR-135b expression increased cell proliferation (B), anchorage-independent colony formation (C) in CAL27 cells. Exogenous miR-135b expression increased the migration of CAL27 cells by transwell chamber (D and E), whereas the blockage of endogenous miR-135b expression using miR-135b LNA complexes decreased the migration of CAL27 cells (D and E). Neg Con, negative control. Mean ± SEM from triplicate or quadruplicate analysis or from at least five mice. (Ns, P > 0.05, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; One-way ANOVA analysis with post-Tukey or Dunnett test).

Cell proliferation was significantly increased in CAL27 cells upon transfection with the miR-135b mimic as compared with the negative control (Fig. 3B). Next, we evaluated the effect of miR-135b on anchorage-dependent cell growth using colony formation assays in adherent cultures. In contrast with the negative control, the number of formed colonies was reduced by miR-135b LNA transfection in the HNSCC cell line (CAL27: P < 0.01;Fig. 3C) and increased by miR-135b mimic transfection (HSC3: P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 3B and C). We performed the trans-well cell migration assay to investigate whether miR-135b could affect HNSCC cell migration. Transfection of the miR-135b mimic led to significantly increased cell migration of both CAL27 (P < 0.01; Fig. 3D and E) and HSC3 cells (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 3D and E).

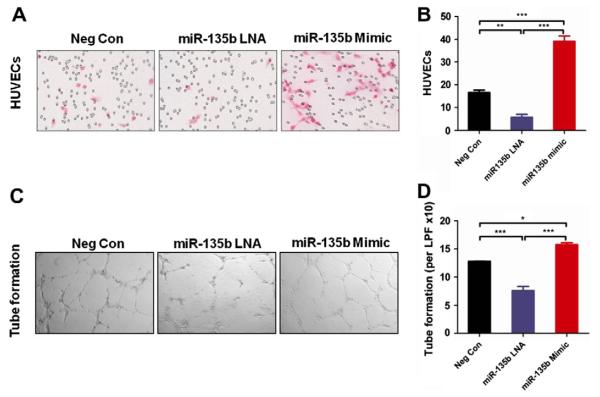

3.5. miR-135b promotes angiogenesis potential of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC)

As shown in Fig. 4A and B, miR-135b LNA significantly inhibits HUVEC migration as compared with the negative control (P < 0.01). Also, the miR-135b mimic significantly promotes HUVEC migration (Fig. 4A and B; P < 0.001). To further confirm the effects of miR-135b on angiogenesis in vitro, we performed a tube formation assay. The results showed that miR-135b mimic promotes HUVEC tube formation (P < 0.001; Fig. 4C and D), and treatment with miR-135b LNA results in a significant decrease in tube formation (P < 0.05; Fig. 4C and D).

Fig. 4.

miR-135b Promotes angiogenic potential of HUVEC cells. (A and B) miR-135b LNA treatment decreased HUVEC migration while the miR-135b mimic promoted HUVEC migration in the transwell chamber migration assay (20×). (C and D) Percentage of tube formation ability of HUVECs with either miR-135b LNA treatment or miR-135b mimic, as compared with negative control. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA analysis with post-Turkey test).

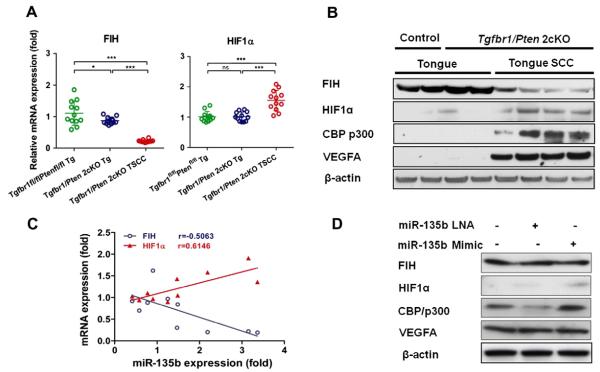

3.6. miR-135b targets FIH

Bioinformatic analysis with TargetScan and/or Pictar systems revealed that hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) and its inhibitor, factor inhibiting HIF (FIH), also known as hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit inhibitor (HIF1AN), are possible targets of miR-135b. We examined Fih and Hif-1α mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR, and the protein levels of FIH, HIF-1α, and VEGFA by Western blotting. Our analysis revealed downregulation of Fih mRNA expression (Fig. 5A) and decreased protein levels (Fig. 5B) in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC, as compared with Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue and Tgfbr1foxl/flox/Ptenflox/flox tongue. Conversely, we found upregulation of Hif-1α mRNA expression (Fig. 5A) and elevated protein levels of HIF-1α, CBP/p300 (a co-activator of HIF-1α), and VEGFA (a downstream target of HIF-1α; Fig. 5B) in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC as compared with controls. The mRNA expression of Fih was inversely associated with miR-135b levels (Fig. 5C; P < 0.001; r = 0.5063) and the expression of Hif-1α was directly associated with miR-135b levels (Fig. 5C; P < 0.001; r = 0.6146). We also demonstrate that miR-135b mimic increases the protein level of HIF-1α, and CBP/p300 and decreases the protein level of FIH in CAL27 cells and HSC3 cells (Fig. 5D and E). These results suggest that miR-135b increases the oncogenic potential of HNSCC cells by increasing stability of HIF-1α and its coactivator CBP/p300, while downregulating FIH.

Fig. 5.

miR-135b Targets FIH. (A) Quantitative PCR of FIH and HIF-1α expression in Tgfbr1flox/flox Pten flox/flox tongue (Green), Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue (blue), and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue SCC tissues. Horizontal lines are the mean values. (Mean ± SEM from triplicate analysis of five mice from each group; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA analysis with post-Turkey test). (B) Western blot of FIH, HIF-1α, CBP/p300, VEGFA, and β-actin of Tgfbr1f1ox/flox/Ptenflox/flox tongue, Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO tongue SCC tissues. (C) Positive linear regression of HIF-1α and negative linear regression of mRNA expression with miR-135b. (D) Western blot analysis of FIH, HIF-1α, CBP/p300, VEGFA and β-actin with exogenous miR-135b mimic or miR-135b LNA treatment in normoxia (two-tailed Pearson test). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

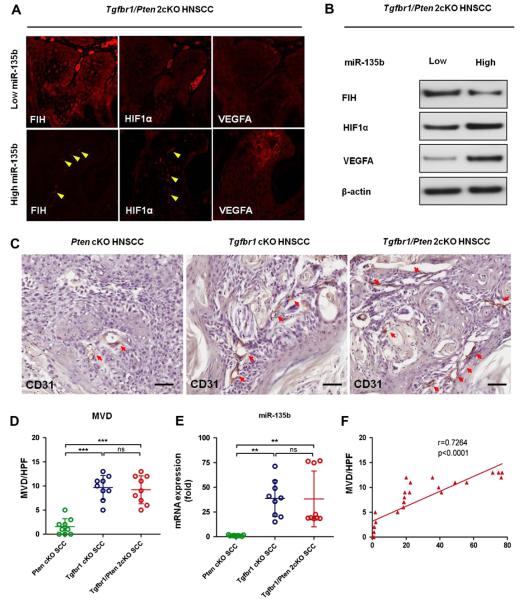

3.7. Decreased FIH and increased HIF-1α and VEGFA expression in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC

Using immunofluorescence, we also compared the localization of FIH, HIF-1α, and VEGFA in paraffin sections of Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC that had higher miR-135b expression (n = 3) with those that had lower miR-135b expression (n = 3). FIH displayed heterogeneity in terms of cellular localization, including in the cytosol and nucleus. Only a weak nuclear FIH level was found in the higher miR-135b expression samples (Fig. 6A), whereas intensive cytosolic and nuclear FIH expression was found in all lower miR-135b expression samples (Fig. 6A). However, stronger nuclear HIF-1α and VEGFA expression was found in the higher miR-135b expression samples (Fig. 6A) versus the amount of cytosolic HIF-1α expression found in lower miR-135b expression samples (Fig. 6A). These observations suggest that staining of FIH in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC tissues was reversely correlated with miR-135b levels, and that higher miR-135b expression correlates with higher HIF-1α and VEGFA expression. This correlation was further confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Expression of FIH correlates with HIF-1α, VEGFA, and MVD in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice HNSCC. (A) Immunofluoroscence of FIH, HIF-1α, and VEGFA. Red staining indicates the immunoreactivity; a representative HNSCC with lower miR-135b expression that is less than the mean (left panel); HNSCC had more nuclear stain of HIF-1α in high miR-135b group (right panel). (B) Western blot of FIH, HIF-1α, and VEGFA in relatively lower and higher miR-135b-expressed Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC. (C) Immunohistochemistry staining of CD31 in Pten cKO, Tgfbr1 cKO, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC tissue (Bar = 50 μM). Quantities of MVD (D) and relative miR-135b expression (E) in Pten cKO, Tgfbr1 cKO, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC tissue (ns, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, One-way ANOVA analysis with post-Turkey test). (F), Correlation and linear regression of miR-135b with MVD in Pten cKO, Tgfbr1 cKO, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC tissue (two-tailed Pearson test).

3.8. Expression of miR-135b was related to microvessel density (MVD) in Pten cKO, Tgfbr1 cKO, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice HNSCC

To further confirm the miR-135b angiogenic potential in vivo, we investigated the correlation of miR-135b with MVD in HNSCC of Pten cKO, Tgfbr1 cKO, and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice. We found that Pten cKO HNSCC (n = 3) has less miR-135b than Tgfbr1 cKO (treated with 7, 12-dimethylbenz (a) anthracene) mice HNSCC (n = 3, P < 0.01) and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mice HNSCC (n = 3, P < 0.01; Fig. 6C). Interestingly, Pten cKO HNSCC also has less MVD than Tgfbr1 cKO HNSCC (mice treated with DMBA; n = 3, P < 0.001, Fig. 6D) and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC (n = 3, P < 0.001; Fig. 6D). Expression of miR-135b was increased in Tgfbr1 cKO HNSCC and Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC (P < 0.01; Fig. 6E), and there was significant correlation with MVD (P < 0.001; R2 = 0.7264; Fig. 6F).

4. Discussion

The carcinogenesis of HNSCC is a multi-step process that encompasses deregulated expression of oncogenes and/or tumor suppressor genes [2]. Among the microRNAs that are identified for their altered expression in human HNSCC, many have already been implicated in tumorigenesis and metastasis in human HNSCC tissues or cell lines. These include miR-31, miR-21, miR-135b, miR-34c, miR-205, miR-133a, and miR-133b [24,34–38]. A recent report indicates that miR-21 may play an important role in TSCC development, suppressing apoptosis in cancer cells in part by silencing TPM1 [39]. STAT3 activation by miR-21, and miR-181b-1 through PTEN, are involved in the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer [40]. However, in the case of a number of candidate miR-NAs implicated in human HNSCCs, the precise roles they play in cancer biology are not clear. Therefore, our Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO mouse HNSCC model, which develops rapid and spontaneous HNSCC tumors with full-penetrance [10,11], will be a powerful tool for investigating the role of oncogenic or tumor suppressor microRNA in vivo. It will also be a good model for preclinical chemotherapeutics of microRNA and its target.

Among the miRNAs whose expression levels are increased in 2cKO HNSCC tumors, miR-135b is the most interesting because its expression is significantly elevated in both human and mouse HNSCC tumors, and its precise function is not clearly known. We found a significant increase in the miR-135b level in 2cKO HNSCC tumors as compared with Pten cKO HNSCC, which partially explains the rapid and full penetrance of spontaneous tumor development in 2cKO mice. Our in vitro analyses further clarified the fact that elevated miR-135b expression was associated with the increased proliferation, migration, and anchorage-dependent colony formation of HNSCC cells, as well as the expression of angiogenic molecules HIF and VEGFA. This suggests potential oncogenic roles for miR-135b in HNSCC. Most importantly, the oncogenic role of miR-135b in squamous cell carcinoma is further confirmed by the study of human tissues. miR-135b is listed as the most upregulated miR-NA in human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma [41,42] and human HNSCC [24]. Even more encouraging is a recent study suggesting that miR-135b may be a potential diagnostic marker [43,44], as well as a prognostic marker [44,45], for colorectal cancer.

Our studies also reveal the potential of miRNA-135b in promoting tumor angiogenesis. The results indicated that miR-135b expression was significantly increased in 2cKO HNSCC and Tgfbr1 cKO HNSCC and, importantly, they show a close correlation with the higher microvessel density. In line with this, the significantly up-regulated expression of VEGFA was observed in 2cKO HNSCC and Tgfbr1 cKO HNSCC. Also of interest is the fact that the in vitro studies showed that direct treatment with miR-135b could promote the migration and tube formation of HUVEC cells [39,40]. These results indicate that the elevated expression of miR-135b may promote tumor angiogenesis through indirect effects on tumor cells as well as through direct effects on endothelial cells. Our findings are in agreement with clinical observations, which state that esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients who have undergone radiochemical treatment and show high expression of miR-135b in their biopsies had significantly shorter median disease-free survival rate [46]. Since hypoxia and drug-resistance triggered by the HIF-1α/VEGFA pathway is an important event in radiotherapy and chemotherapy [47], the role of miR-135b in hypoxia and angiogenesis warrants further investigation in order to gain insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to drug and radiotherapy.

Our data suggests that miR-135b promotes angiogenesis effects through activation of HIF-1α. HIF-1α is a key transcription factor induced by hypoxia through the Akt/mTOR canonical pathway [48], and it activates a transcription program that promotes aggressive tumor phenotypes by triggering the expression of critical genes, including VEGFA [47]. Meanwhile, recent studies also suggest that HIF-1α can be accumulated and activated by certain stimuli under normoxic conditions [49,50], and may involve the degradation of FIH [49]. Generally, FIH serves as an inhibitor of HIF-1α during normoxia and hydroxylates Asn803 of HIF-1α, preventing interaction of this subunit with transcriptional coactivators such as CBP/p300. In the present study, we identify FIH as an important target of miR-135b. The in vitro studies showed that miR-135b could significantly suppress the expression of FIH even under normoxic conditions, which may consequently increase the stability of HIF-1α protein, as well as its downstream target, VEGFA. Moreover, the data also suggested that this action by miR-135b may involve the participation of HIF-1α coactivator CBP/p300, as demonstrated by the corresponding upregulation of CBP/p300 in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO TSCC. These findings indicate that, besides the canonical Pten/Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α signaling pathway, the Tgfbr1/miR-135b/FIH/HIF-1α cascade may be involved in HNSCC tumorigenesis and the promotion of angiogenesis. We have demonstrated here that deletion of TGFBR1 may regulate HIF-1α through increased expression of miR-135b and the consequent downregulation of FIH. Since the TGF-β pathway may play dual roles during different stages of cancer [5,51], and expression of miR-135b may regulate or be regulated by TGF-β, the expression level of miR-135b may vary during different stages of cancer (i.e. during premalignancy, early stage, advanced stage, metastasis, and post-radiochemical therapy). It has been suggested by clinical observation that miR-135b may be significantly downregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma, particularly in the advanced stage with or without lymph node metastasis [52]. Keeping this in mind, further clinical observations, as well as studies aimed at delineating the underlying molecular mechanisms, are needed in order to understand the role of this intriguing miRNA.

In conclusion, our study reveals that miR-135b functions as an oncogenic miRNA by increasing cancer cell proliferation, migration, and colony formation, as well as by promoting angiogenesis through downregulation of FIH expression and activation of the HIF pathway in Tgfbr1/Pten 2cKO HNSCC and human HNSCC cell lines. Our study also suggests that, except for the canonical mTOR-dependent regulation of the HIF pathway, deletion of TGFBR1 may also increase HIF-1α expression by increasing miR-135b levels and downregulating FIH levels. Therefore, miR-135b may prove to be a potential target for the development of novel anticancer therapies to treat HNSCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Carter Van Waes and Dr. Hynda Kleinman for critical reading of the manuscript, and Shelagh Johnson for expert editorial assistance. This work was supported by Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH to ABK (ZIA-DE-000698), and National Natural Science Foundation of China to ZJS (81072203, 81272963).

Appendix A. Supplementary data.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.003.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics, CA Cancer. J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, Fakhry C, Xie TX, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhang N, El-Naggar AK, Jasser SA, Weinstein JN, Trevino L, Drummond JA, Muzny DM, Wu Y, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Westra WH, Koch WM, Califano JA, Gibbs RA, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Wheeler DA, Kinzler KW, Myers JN. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, Kostic AD, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Kryukov GV, Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, McKenna A, Shefler E, Ramos AH, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Voet D, Cortes ML, Auclair D, Berger MF, Saksena G, Guiducci C, Onofrio RC, Parkin M, Romkes M, Weissfeld JL, Seethala RR, Wang L, Rangel-Escareno C, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Melendez-Zajgla J, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Gabriel SB, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G, Golub TR, Garraway LA, Grandis JR. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].White RA, Malkoski SP, Wang XJ. TGFbeta signaling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:5437–5446. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perez-Sayans M, Suarez-Penaranda JM, Pilar GD, Barros-Angueira F, Gandara-Rey JM, Garcia-Garcia A. Hypoxia-inducible factors in OSCC. Cancer Lett. 2011;313:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Frese KK, Tuveson DA. Maximizing mouse cancer models. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:645–658. doi: 10.1038/nrc2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lu SL, Herrington H, Reh D, Weber S, Bornstein S, Wang D, Li AG, Tang CF, Siddiqui Y, Nord J, Andersen P, Corless CL, Wang XJ. Loss of transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor promotes metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1331–1342. doi: 10.1101/gad.1413306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bian Y, Terse A, Du J, Hall B, Molinolo A, Zhang P, Chen W, Flanders KC, Gutkind JS, Wakefield LM, Kulkarni AB. Progressive tumor formation in mice with conditional deletion of TGF-beta signaling in head and neck epithelia is associated with activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5918–5926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bian Y, Hall B, Sun ZJ, Molinolo A, Chen W, Gutkind JS, Waes CV, Kulkarni AB. Loss of TGF-beta signaling and PTEN promotes head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through cellular senescence evasion and cancer-related inflammation. Oncogene. 2012;31:3322–3332. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sun ZJ, Zhang L, Hall B, Bian Y, Gutkind JS, Kulkarni AB. Chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic actions of mTOR inhibitor in genetically defined head and neck squamous cell carcinoma mouse model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:5304–5313. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davis-Dusenbery BN, Hata A. Mechanisms of control of microRNA biogenesis. J. Biochem. 2010;148:381–392. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bushati N, Cohen SM. MicroRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Winter J, Diederichs S. MicroRNA biogenesis and cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;676:3–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-863-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ruan K, Fang X, Ouyang G. MicroRNAs: novel regulators in the hallmarks of human cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Budhu A, Ji J, Wang XW. The clinical potential of microRNAs. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2010;3:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garzon R, Marcucci G, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garofalo M, Croce CM. MicroRNAs: master regulators as potential therapeutics in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;51:25–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang J, Wang Q, Liu H, Hu B, Zhou W, Cheng Y. MicroRNA expression and its implication for the diagnosis and therapeutic strategies of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu X, Chen Z, Yu J, Xia J, Zhou X. MicroRNA profiling and head and neck cancer. Comp. Funct. Genom. 2009:837514. doi: 10.1155/2009/837514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ramdas L, Giri U, Ashorn CL, Coombes KR, El-Naggar A, Ang KK, Story MD. MiRNA expression profiles in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and adjacent normal tissue. Head Neck. 2009;31:642–654. doi: 10.1002/hed.21017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. MiR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu CJ, Tsai MM, Hung PS, Kao SY, Liu TY, Wu KJ, Chiou SH, Lin SC, Chang KW. MiR-31 ablates expression of the HIF regulatory factor FIH to activate the HIF pathway in head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1635–1644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, Malumbres R, Zarate R, Ramirez N, Abajo A, Navarro A, Moreno I, Monzo M, Garcia-Foncillas J. Identification by real-time PCR of 13 mature microRNAs differentially expressed in colorectal cancer and non-tumoral tissues. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lowery AJ, Miller N, Devaney A, McNeill RE, Davoren PA, Lemetre C, Benes V, Schmidt S, Blake J, Ball G, Kerin MJ. MicroRNA signatures predict oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2/neu receptor status in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R27. doi: 10.1186/bcr2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sarver AL, French AJ, Borralho PM, Thayanithy V, Oberg AL, Silverstein KA, Morlan BW, Riska SM, Boardman LA, Cunningham JM, Subramanian S, Wang L, Smyrk TC, Rodrigues CM, Thibodeau SN, Steer CJ. Human colon cancer profiles show differential microRNA expression depending on mismatch repair status and are characteristic of undifferentiated proliferative states. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:401. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ostling P, Leivonen SK, Aakula A, Kohonen P, Makela R, Hagman Z, Edsjo A, Kangaspeska S, Edgren H, Nicorici D, Bjartell A, Ceder Y, Perala M, Kallioniemi O. Systematic analysis of microRNAs targeting the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1956–1967. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nagel R, le Sage C, Diosdado B, van der Waal M, Oude Vrielink JA, Bolijn A, Meijer GA, Agami R. Regulation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene by the miR-135 family in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5795–5802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Necela BM, Carr JM, Asmann YW, Thompson EA. Differential expression of microRNAs in tumors from chronically inflamed or genetic (APC(Min/+)) models of colon cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kawakami K, Kawakami M, Joshi BH, Puri RK. Interleukin-13 receptor-targeted cancer therapy in an immunodeficient animal model of human head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6194–6200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sun ZJ, Chen G, Zhang W, Hu X, Huang CF, Wang YF, Jia J, Zhao YF. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway promotes tumor-induced angiogenesis in adenoid cystic carcinoma: its suppression by isoliquiritigenin through dual activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;334:500–512. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sun ZJ, Chen G, Zhang W, Hu X, Liu Y, Zhou Q, Zhu LX, Zhao YF. Curcumin dually inhibits both mammalian target of rapamycin and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways through a crossed phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/IkappaB kinase complex signaling axis in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;79:106–118. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kimura S, Naganuma S, Susuki D, Hirono Y, Yamaguchi A, Fujieda S, Sano K, Itoh H. Expression of microRNAs in squamous cell carcinoma of human head and neck and the esophagus: miR-205 and miR-21 are specific markers for HNSCC and ESCC. Oncol. Rep. 2010;23:1625–1633. doi: 10.3892/or_00000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Childs G, Fazzari M, Kung G, Kawachi N, Brandwein-Gensler M, McLemore M, Chen Q, Burk RD, Smith RV, Prystowsky MB, Belbin TJ, Schlecht NF. Low-level expression of microRNAs let-7d and miR-205 are prognostic markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:736–745. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jiang J, Lee EJ, Gusev Y, Schmittgen TD. Real-time expression profiling of microRNA precursors in human cancer cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5394–5403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liu X, Yu J, Jiang L, Wang A, Shi F, Ye H, Zhou X. MicroRNA-222 regulates cell invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) and manganese superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Genom. Proteomics. 2009;6:131–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wong TS, Liu XB, Wong BY, Ng RW, Yuen AP, Wei WI. Mature miR-184 as potential oncogenic microRNA of squamous cell carcinoma of tongue. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:2588–2592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li J, Huang H, Sun L, Yang M, Pan C, Chen W, Wu D, Lin Z, Zeng C, Yao Y, Zhang P, Song E. MiR-21 indicates poor prognosis in tongue squamous cell carcinomas as an apoptosis inhibitor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3998–4008. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Iliopoulos D, Jaeger SA, Hirsch HA, Bulyk ML, Struhl K. STAT3 activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD are part of the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Xu N, Zhang L, Meisgen F, Harada M, Heilborn J, Homey B, Grander D, Stahle M, Sonkoly E, Pivarcsi A. MicroRNA-125b down-regulates matrix metallopeptidase 13 and inhibits cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:29899–29908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.391243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sand M, Skrygan M, Georgas D, Sand D, Hahn SA, Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Bechara FG. Microarray analysis of microRNA expression in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012;68:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kanaan Z, Rai SN, Eichenberger MR, Roberts H, Keskey B, Pan J, Galandiuk S. Plasma miR-21: a potential diagnostic marker of colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 2012;256:544–551. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265bd6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gaedcke J, Grade M, Camps J, Sokilde R, Kaczkowski B, Schetter AJ, Difilippantonio MJ, Harris CC, Ghadimi BM, Moller S, Beissbarth T, Ried T, Litman T. The rectal cancer microRNAome–microRNA expression in rectal cancer and matched normal mucosa. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:4919–4930. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu XM, Qian JC, Deng ZL, Cai Z, Tang T, Wang P, Zhang KH, Cai JP. Expression of miR-21, miR-31, miR-96 and miR-135b is correlated with the clinical parameters of colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2012;4:339–345. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ko MA, Zehong G, Virtanen C, Guindi M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S, Darling GE. MicroRNA expression profiling of esophageal cancer before and after induction chemoradiotherapy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012;94:1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:393–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:851–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fukuba H, Takahashi T, Jin HG, Kohriyama T, Matsumoto M. Abundance of aspargynyl-hydroxylase FIH is regulated by Siah-1 under normoxic conditions. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;433:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Metzen E, Zhou J, Jelkmann W, Fandrey J, Brune B. Nitric oxide impairs normoxic degradation of HIF-1alpha by inhibition of prolyl hydroxylases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:3470–3481. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Lo Muzio L, Pezzetti F, Rubini C, Girardi A, Farinella F, Mazzotta M, Carinci F. MicroRNA expression profiling of oral carcinoma identifies new markers of tumor progression. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011;23:1229–1234. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.