Abstract

The glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are a family of phase II detoxification enzymes which protect against chemical injury. In contrast to mammals, GST expression in fish has not been extensively characterized, especially in the context of detoxifying waterborne pollutants. In the Northwestern United States, coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) are an important species of Pacific salmon with complex life histories that can include exposure to a variety of compounds including GST substrates. In the present study we characterized the expression of coho hepatic GST to better understand the ability of coho to detoxify chemicals of environmental relevance. Western blotting of coho hepatic GST revealed the presence of multiple GST-like proteins of approximately 24–26 kDa. Reverse phase HPLC subunit analysis of GSH affinity-purified hepatic GST demonstrated six major and at least two minor potential GST isoforms which were characterized by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC/ESI MS–MS) and Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS analyses. The major hepatic coho GST isoforms consisted of a pi and a rho-class GST, whereas GSTs representing the alpha and mu classes constituted minor isoforms. Catalytic studies demonstrated that coho cytosolic GSTs were active towards the prototypical GST substrate 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene, as well as towards ethacrynic acid and nitrobutyl chloride. However, there was no observable cytosolic GST activity towards the pesticides methyl parathion or atrazine, or products of oxidative stress, such as cumene hydroperoxide and 4-hydroxynonenal. Interestingly, coho hepatic cytosolic fractions had a limited ability to bind bilirubin, reflecting a potential role in the sequestering of metabolic by-products. In summary, coho salmon exhibit a complex hepatic GST isoform expression profile consisting of several GST classes, but may have a limited a capacity to conjugate substrates of toxicological significance such as pesticides and endogenous compounds associated with cellular oxidative stress.

Keywords: Glutathione S-transferases, Coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, Pesticides, LC–MS/MS

1. Introduction

The glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are a phase II detoxification enzyme family that can mitigate the cellular toxicity of a number of endogenous and environmental chemicals. At present, at least eight classes of mammalian GST have been identified based on primary amino acid sequences, and include alpha, mu, pi, sigma, theta, omega, kappa, and zeta GSTs. GSTs sharing more than 40% identity are generally assigned to the same class, and those sharing less than 30% assigned to different classes (Hayes and Pulford, 1995). The primary catalytic activity of GSTs is the conjugation of electrophilic compounds by facilitating nucleophilic attack by reduced glutathione (GSH). Certain GST isoforms may also combat oxidative stress damage by GSH-dependent peroxidase activity, while other isoforms conjugate reactive α-β-unsaturated aldehydes produced during lipid membrane peroxidation (Hayes and Pulford, 1995). Environmental chemicals detoxified by GSTs include carcinogens, pesticides, and reactive intermediates. Thus, GST isoform expression is of relevance when considering susceptibility to chemical injury (for a review, see Eaton and Bammler, 1999). For example, the pesticide atrazine is preferentially detoxified by pi-class GSTs in mice and humans (Abel et al., 2004b), while methyl parathion is dealkylated by alpha class GSTs in rats and mice, and by alpha- and mu-class GSTs in humans (Abel et al., 2004a). Furthermore, the resistance of mice to the hepatocarcinogenic effects of aflatoxin B1 is largely due to the selective constitutive expression of an alpha class GST (mGSTA3-3) which has an unusually high catalytic efficiency towards detoxifying the mutagenic aflatoxin B1-8,9-epoxide (AFB1).

Although GSTs in fish have not been characterized to the extent of their mammalian counterparts, all fish species examined to date have been shown to have GST catalytic activity and express soluble hepatic GST isoforms with some structural similarity to the rodent GSTs. Specifically, GST proteins related to rodent alpha-, mu- and pi-class GST have been identified as the major GST isoforms identified in brown bullhead (Ameriurus nebulosus) and largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (Doi et al., 2004), juvenile white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) (Donham et al., 2005a), chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) (Donham et al., 2005b), and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (George, 1994). In addition, a relatively new GST class termed “rho” has been proposed based upon an isoform isolated from the hepatopancreas of the red sea bream (Pagrus major) which is homologous to GST-A in plaice and largemouth bass, and clusters structurally with GST isoforms from several other fish species (Konishi et al., 2005).

Of particular importance in the Pacific Northwestern United States are the causal mechanisms underlying the decline of Pacific salmon (e.g. coho, chinook, pink, and sockeye salmon) populations (Quinn, 2005). The life histories of these species often include residence and migration through urban and agricultural waterways that are contaminated with metals, pesticides, herbicides, and persistent pollutants (Hoffman et al., 2000). Functionally, chemical exposures have caused DNA damage and reduced growth in juvenile chinook salmon (Collier et al., 1998; Varanasi et al., 1993), and altered behaviors in coho, chinook, and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) that are critical to survival (Moore and Lower, 2001; Sandahl et al., 2005; Scholz et al., 2000). Furthermore, the effects observed in Pacific salmon can occur at waterborne concentrations below those associated with water quality guidelines (Wentz et al., 1998). Accordingly, the ability of these species to mount protective cellular responses to chemical exposures is likely to contribute to survival. In this regard, many of the chemicals salmon are exposed to (i.e. pesticides, PAH intermediates) are GST substrates, while other compounds such as trace metals have the capacity to directly or indirectly generate GST substrates via cellular oxidative damage pathways.

Recently, Donham et al. identified alpha, mu, pi and theta-like GST in chinook salmon (Donham et al., 2005b), whereas pi-like GSTs are major isoforms in rainbow trout, Atlantic salmon and brown trout (Salmo trutta) (Dominey et al., 1991; Novoa-Valinas et al., 2002). In general however, little is known regarding the ability of salmonid GSTs to protect against environmental chemicals commonly encountered in polluted surface waters. The present study was initiated to characterize the expression and catalytic function of coho salmon GST. Our approach was to characterize and identify the major GST isoforms in coho liver by using a combination of biochemical and proteomic techniques. We were also interested in GST isoforms involved in protecting against model pesticides and mutagenic by-products of oxidative stress, compounds of toxicological concern to coho salmon. Our results indicate a complex GST expression profile in coho salmon comprising several GST classes, suggesting that coho liver GST play a role in binding and transporting endogenous products. However, we observed a limited potential for coho hepatic GST to detoxify certain pesticides and compounds relevant to cellular oxidative damage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Reduced glutathione (GSH), dithiolthreitol (DTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), tetrabutyl ammonium phosphate (TBAP), ammonium carbonate, iodoacetamide (IAD), cumene hydroperoxide (CumOOH), and GSH-agarose (GSHA) were obtained from Sigma Chemical (San Francisco, CA). Ammonium persulfate (APS), ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), Tris-HCl, Tris base, sodium chloride, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 4-nitrobenzyl chloride (NBC), and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) were acquired from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Ethacrynic acid (ECA) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were purchased from MP Biomedical (Irvine, CA). Dichloromethane (DCM), sucrose and HPLC-grade acetonitrile were obtained from J.T Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ) and Δ5-androstene-3,17-diol (ADI) was purchased from Steraloids Inc. (Wilton, NH). 4-Hydroxynonenal (4HNE) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), whereas methyl parathion (MeP) and atrazine were obtained from ChemService (West Chester, PA). Bilirubin was acquired from VWR Scientific (West Chester, PA) and 1,2-dinitro-4-chlorobenzene (DCNB) was acquired from Acros Chemical Inc. (Morris Plains, NJ). Sequencing grade trypsin was obtained from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Bradford reagent, acrylamide, bis-acrylamide, BioRad precision plus protein standards, SYPRO® ruby stain, and Immuno-blot PVDF membranes were obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA). The polyclonal striped bass GST antibody was a generous gift of Drs. Hank Segall and Michael Lamé of the University of California, whereas 14C atrazine was provided by Dr. David Eaton, University of Washington. All other chemicals were of reagent grade or better and were obtained from commercial sources.

2.2. Animals

Juvenile coho salmon (1 year of age) were provided by the National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Seattle Washington. Fish were raised in cylindrical tanks with recirculated freshwater at 11–12°C under a natural photoperiod in dechlorinated municipal water. The fish were fed BioOregon diet and water quality conditions were typically 120 mg/L total hardness as calcium carbonate, pH 6.6, and 8.1 mg/L dissolved oxygen content. Fish were anesthetized with tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) prior to cervical dislocation and organ harvest. Liver tissues were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and held at −80 °C until use.

2.3. Subcellular fractionations and GSH affinity purification ofcoho hepatic GST

Preparations of hepatic subcellular fractions were carried out using the method of Gallagher et al. (Gallagher et al., 2000) with minor modifications. Briefly, coho liver tissue was thawed in ice-cold 0.95% potassium chloride (KCl), weighed, and homogenized 1:2 (w/v) in ice-cold buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF; pH 7.4) using an IKA-Ultra-Turrax T2 tissue homogenizer for one 30 s burst. All subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C. The tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20min, and the supernatant was recentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 70 min. The fatty layer was removed manually with a cotton swab and the cytosolic fraction was removed, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C prior to biochemical analysis or GSH affinity purifications.

To affinity purify hepatic GST, 3 mL of hepatic cytosol was diluted 1:10 in 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT (pH 6.5; Buffer A). The GSHA matrix was prepared according to manufacturers' instructions and gravity packed into a 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm column. The column was equilibrated in 10 column volumes of Buffer A and the diluted cytosol was applied and allowed to elute under gravity. The column was then rinsed using 15 mL Buffer B (Buffer A with 0.5 M NaCl, pH 6.5) prior to the elution of GST with Buffer C (Buffer B containing 50 mM GSH, pH 9.6). Fractions eluting from the column were collected and assayed for GST-CDNB activity. Catalytically active fractions were pooled, then buffer exchanged to remove residual salt and GSH using 10MWCO centrifuge filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) prior to storage at −80 °C.

2.4. Gel electrophoresis and GST immunoblotting

Cytosolic and affinity-purified coho liver proteins (5–100 μg) were separated on a 12% acrylamide gel with a 5% stacking gel (Donham et al., 2005b). Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and the separated proteins visualized with SYPRO®-ruby staining. For Western blotting analysis, the proteins were electrophoresed and transferred as described above, but were not stained, and instead immunoreacted against polyclonal striped bass GST antisera (1:15,000 in non-fat dried milk) which cross-reacts with GST proteins from a number of fish GST species (Gallagher et al., 2000; Gardner et al., 2003, unpublished observations). Goat-anti-rabbit IgG (1:15,000) was used as the secondary antibody and the immunoreacted proteins were visualized using BioRad ECL reagent followed by autoradiography.

2.5. GST subunit analysis by reverse phase HPLC

GSHA-purified hepatic GST was concentrated to 1 μg/μL and 100 μL combined with 1 μL triflouroacetic acid (TFA) prior to injection onto a 150 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μM C4 column (Grace Vydac, Hesperia, CA) equilibrated with 27% (v/v) acetonitrile containing 0.045% TFA. The column flow rate was 1.5 mL/min with initial conditions held for 5 min followed by a 27–43% gradient over 23 min. Peaks were detected using a Shimadzu UV-vis detector (λ = 214nm) and integrated using Peakchem (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) software. GST fractions were collected post-detection, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining, whereas other aliquots were dried under vacuum to remove solvent prior to trypsin digestion (see Section 2.6).

2.6. LC ESI–MS/MS analysis of digested proteins in HPLC peaks

After solvent removal, the GST proteins were reconstituted in 100 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 6 M urea. Following reconstitution, 7 μL of 1.5 M Tris (pH 8.8) was added to buffer the sample prior to denaturating by the addition of 2.5 μL of 200 mM tris[2-carboxyethyl] phosphine (TCEP) and incubating for 1 h at 37 °C. The proteins were alkylated by incubating with 20 μL of 200 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) for 1 h in the dark at room temperature, and the reactions were neutralized by the addition of 20 μL of 200 mM DTT. Samples were then diluted with 900 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate followed by addition of 20% (v/v) methanol and trypsin digested (1:40 v/v sequencing grade trypsin) at room temperature. After trypsin digestion, the samples were evaporated to dryness and recovered by collecting several 200 μL ammonium bicarbonate washes followed by an additional wash in 125 μL 5% ACN/0.1% TFA. The reconstituted, digested GST proteins were then desalted using C18 ultra microspin columns (Nest Group, Southborough, MA) according to manufacturer's instructions.

On-line nano-LC/ESI-MS/MS experiments were performed on an API-US QTOF mass spectrometer (Micromass Inc., UK) equipped with the Nano Acquity LC system (Waters Inc., Mil-ford, MA). Peptide samples (5 μL) were loaded and desalted on an 180 μm ID × 20 mm trap column packed with Symmetry C18 5 μm particles connected in series with a 75 μm ID × 150 mm analytical column operated at a flow rate of 400 nL/min. The analytical column was packed according to the pressurized bomb method described (Kennedy and Jorgenson, 1989) using a 360 μm OD × 75 μm ID × 20 cm fused-silica column with an integral frit (PicoFrit, New Objective Inc., Cambridge, MA). The gradient consisted of 5–50% solvent B over 45 min, followed by 50% B for 10min (solvent A = 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid; solvent B = 95% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid). The QTOF parameters were as follows: electrospray potential 3.5 kV, cone voltage 32 V, extraction cone voltage 1V, and source temperature 100 °C. The MS survey scan was m/z 400–1700 with a scan time of 1 s and the collision energy was set to 5 eV For the MS/MS-mode, the scan time was increased to 2 s and the isolation width was set to include the full isotopic distribution of each precursor (4 Da mass window). Doubly and triply protonated peptide ions selected by the data-dependant software were subjected to collision-induced dissociation (CID) using collision energies of 16–40 eV Upon completion of an LC/MS/MS run, the MS/MS spectra were searched against the non-redundant NCBI protein database using MASCOT (Matrix Science, London, UK) and against the Swiss Prot database using Phenyx software program (Geneva Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland).

2.7. Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer analysis of digested SDS-PAGE separated GST proteins

GST proteins analyzed by SDS-PAGE were excised from the acrylamide gel and prepared for mass spectrometry. Briefly, the gel sections were washed 3× with 1mL 50 mM NH4HCO3, dehydrated in acetonitrile (ACN) and finally dried under vacuum. The proteins were then preincubated on ice for 45 min in 50 μL of 12.5 ng/μL trypsin in 50 mM NH4HCO3, and an equal amount of 50 mM NH4HCO3 without trypsin was added and the samples incubated overnight at room temperature. After incubation, the liquid was centrifuged for collection and removed. Gel sections were rinsed twice in 50 μL of 5% ACN/0.1% TFA, followed by a wash in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA. The liquids from each wash were collected and combined with the initial protein digest. Samples were then dried to 10–20 μL total volume under vacuum and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Peptide digests were analyzed by electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode on a hybrid linear ion trap-Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA). Nanoflow HPLC was performed using a Michrom Bioresources Paradigm MS4B LC system (Auburn, CA). The precolumn consisted of a 100 μm ID fused-silica capillary packed with C18. Peptides were separated on a 75 μm ID fused-silica capillary column with a gravity-pulled tapered tip packed with C18. The peptides were loaded on the precolumn at arate of 10 μL/min in 95% H2O/5% CH3CN containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and eluted over 90 min using an acetonitrile gradient. Ion source conditions were optimized using a calibration solution and injection waveforms for the LTQ-FT linear ion trap and ICR cell were monitored for all acquisitions. For MS analysis, ICR resolution was set to 100,000 (m/z 400) and ICR ion populations were held at 1,000,000. For MS/MS in the linear ion trap, the ion population was set to 10,000, the precursor isolation width was set to 2 Da, and the collision energy set to 35%. Following data acquisition, MS/MS data-dependent selection of the five most abundant precursors from the survey scan in the linear ion trap. Singly charged ions were excluded from data-dependent analysis. Data redundancy was minimized by excluding previously selected precursor ions (−0.1 Da/+1.1 Da) for 60 s following their selection for MS/MS. Data was acquired using Xcalibur Version 1.4 (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA).

2.8. GST catalytic activity assays

The initial rate enzymatic activities of coho hepatic cytosolic GST toward the reference substrates CDNB, ECA, CumOOH, ADI, DCNB, and NBC were determined using a SpectraMax 190 UV–vis 96-well microplate reader as previously described (Gallagher et al., 2000). To establish GST-DCM initial rate kinetics, DCM (5 mM) was incubated at room temperature with cytosol in 0.1M Tris buffer (pH 8.5) containing 10 mM GSH (Thier et al., 1996). Aliquots were removed at 10 min intervals and the reactions quenched with 25% TCA. After centrifuging to remove protein, equal volumes of supernatant and Nash reagent (2M ammonium acetate, 50 mM acetic acid, 20 mM acetyl acetone) were then incubated for 30 min at 42 °C. After incubation absorbance due to formaldehyde (the product of GST-DCM metabolism) was measured at 412 nm and the slope of the reaction was determined by plotting absorbance over time. GST catalytic activity toward 4HNE was assayed using the method Gardner et al. (2003) on a Shimadzu UV-160 dual beam spectrophotometer.

The rate of GST-mediated dealkylation of methyl parathion was measured as described (Abel et al., 2004a) with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 μL of enzyme (coho or mouse liver cytosol, or coho affinity-purified GST) was added to 145 μL incubation buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7.4) containing 10 mM GSH. Methyl parathion dissolved in DMSO was added for a final assay concentration of 300 μM. The samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with shaking and the reaction was quenched with ice-cold methanol containing 250 μM p-phenylphenol as an internal standard. Samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 10,000 × g to remove proteins and 200 μL aliquots were removed for methyl parathion analysis. All samples were run in triplicate with mouse cytosol used as a positive control and denatured coho cytosol used to quantitate non-enzymatic activity. The rate of GST-catalyzed methyl parathion dealkylation was estimated by using HPLC analysis to quantify the loss of parent compound. The samples were injected onto an Econosphere C18 4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μM particle size column (Alltech, Deerfield, IL) with a Shimadzu SIL-10Advp auto-injector. The column was heated to 40 °C (Shimadzu CTO-10A column oven) and the peaks were detected with a Shimadzu SPD-10A UV–vis detector (λ = 254).

The rate of GST-mediated atrazine conjugation was determined according to Abel et al. (2004b). Briefly, 14C atrazine (137 μM) was incubated with 3 mM GSH and enzyme in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 60 min with shaking at room temperature. The reaction was quenched with an equal volume of chloroform, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged 5 min at 12,000 × g. The aqueous portion was sampled for 14C atrazine mercapturate metabolites on a Beckman LS6000 scintillation counter equipped with quenching curve. Mouse cytosolic fractions were used as a positive control in parallel reactions.

2.9. Inhibition of GST-CDNB catalytic activity by endogenous and environmental agents

To asses the ability of endogenous or environmental chemicals to inhibit coho liver GST activity, coho liver cytosolic fractions (or non-enzymatic controls) were preincubated in buffer (0.1 M K2HPO4, pH 7.5), and 5mM GSH for 10 min at room temperature in the presence of inhibitor or an equal volume of vehicle control (final reaction mixtures contained <5% vehicle). The inhibitors tested were bilirubin (50 μM), methyl parathion (50 and 100 μM), chlorpyrifos (50 and 100 μM), and atrazine (100 μM). Bilirubin reactions were incubated in the dark to maintain bilirubin integrity (Ivanetich et al., 1990). The reactions were initiated by adding 1 mM CDNB and the initial rate GST-CDNB activities were measured as described above.

3. Results

3.1. GSH affinity purification of hepatic GST

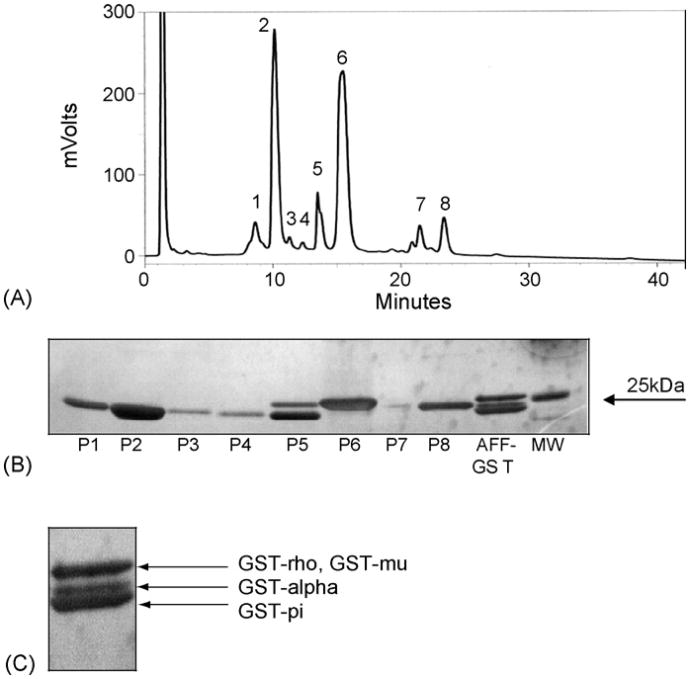

Table 1 presents a summary of typical coho cytosolic GST protein and GST-CDNB activity yields from the GST affinity purification process. As observed, approximately 80% of total protein was accounted for through the GSHA purification process. Approximately 50% of the GST-CDNB activity present in cytosol was retained by the GSHA column, whereas an additional 10% activity was unretained, yielding 60% of the total GST-CDNB activity for the purification process. GSHA-affinity purification resulted in a 97-fold enrichment of cytosolic GST based on per milligram increase in GST-CDNB activity (Table 1). As observed in Fig. 1A, the GST purification process removed essentially all proteins outside the 22–27 kDa range, and enriched at least three proteins of approximately 25 kDa. Immunoblotting of coho liver cytosolic, GSHA-retained, and GSHA flow-through fractions established the presence of GSTlike proteins in all samples (Fig. 1B) with at least three distinct proteins that cross-reacted with the polyclonal bass antibody visible in the cytosolic and GSHA fractions. Immunoblotting of the GSHA-unretained fraction revealed only one band that cross-reacted with the fish GST antisera, consistent with the presence of GST-CDNB activity in the unretained fraction (Table 1).

Table 1. Typical protein content and GST-CDNB activity during affinity purification of coho liver cytosolic GST.

| Fraction | Total protein (mg) | % total protein | Total GST-CDNB activity (nmol/min) | % of starting CDNB activity | Specific CDNB activity (nmol/min/mg) | Fold enrichment of GST-CDNB activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | 226 | 100 | 70,917 | 100 | 314 | – |

| Unretained fraction | 180 | 80 | 7,924 | 11 | 44 | – |

| Retained fraction | 1.1 | 0.5 | 33,608 | 48 | 31,189 | 97 |

| Recovery | 181 | 81 | 41,532 | 59 | – | – |

Fig. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis and Western blotting analysis of coho hepatic cytosolic fractions. (A) SYPRO® ruby stain of cytosolic protein and affinity-purified GST showing removal of proteins outside the 22–27 kDa range by GSHA purification (right lane), (B) Western blot analysis of coho hepatic cytosolic fractions (left lane), GSHA-purified cytosol (right lane), and GSHA-unretained fraction (middle lane) fractions.

3.2. GST subunit analysis by reverse phase HPLC

Reverse phased HPLC separation of GSHA-purified proteins revealed the presence of two major and six minor peaks absorbing at 224 nm (Fig. 2A). When the fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining, all visible proteins eluted in the molecular weight range consistent with GST (i.e. 23–27 kDa, Fig. 2B). As observed in Fig. 2A, peaks two and six constituted the major GST-like proteins based upon area under the curve analysis. Peak 5 consisted of at least two proteins as determined by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 2B). Attempts to further resolve peak 5 by RP-HPLC gradient modifications were unsuccessful (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of coho hepatic GST subunits by reverse phased HPLC. (A) Representative chromatogram of coho liver GSHA-purified GST separated by reversed phase HPLC reveals six major (peaks 1–6) and at least two minor (peaks 7 and 8) protein peaks absorbing at 224 nm. Peaks 1–4 were identified as being pi-like, peak 5 contained both mu- and pi-like isozymes. Peak 6 was composed of a rho-like GST, and peaks7and8were identified as being alpha-like GST. (B) SDS-PAGE silver staining of protein fractions eluting by HPLC from (A). As observed, peak 5 contains two proteins with distinct molecular masses. Affinity-purified (AFF-GST) GST serves as a reference in lane 9. (C) silver stain of affinity-purified GST protein with putative isozyme identifications.

3.3. MS peptide sequencing and MALDI-TOF analyses

Peptide sequences derived from the MS analysis of the trypsin digested peaks were putatively identified by BLAST analysis against the SwisProt and NCBI databases. As observed in Table 2, peaks 1–5 were homologous to sockeye salmon GST-pi (NCBI AB026119) with peptide coverage ranging from 11 to 62%, depending upon the peak analyzed. Peptide sequence homology for each peak across the covered area of the protein was 100%, with the exception of peak 5 in which homology to sockeye salmon GST-pi was 97% due to a serine-to-threonine amino acid substitution at position 47. As observed in Table 2, three peptides from peak 5, a doublet peak, exhibited 100% homology over 19% of the zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio) GST-mu (NCBI BC057526) protein. The presence of two differing GST isozymes in peak 5 was expected since the peak was comprised of two proteins with differing molecular masses (Fig. 2B). LC–MS analysis of peak 5 protein bands separated using SDS-PAGE identified the upper band as GST-mu and the lower band as GST-pi (Fig. 2C).

Table 2. LC/MS analysis of GST subunits from coho liver.

| Peak | HPLC peak sequence | Matched sequence | Class | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MGPYTITYFGVR ASCVFGQLPKFEDGG IDMMCDGVEDLR MIYQEYDTGKDQYI KDLPNHLDKFEAVMAK IKAFLGSDAYK |

MGPYTITYFGVR ASCVFGQLPKFEDGG IDMMCDGVEDLR MIYQEYDTGKDQYI KDLPNHLDKFEAVMAK IKAFLGSDAYK |

pi | sockeye salmon (AB026119) |

| 2 | MGPYTITYFGVR IMMADQGQEWK EILMDFADWTK GDLKASCVFGQLPKFEDGG LVLYQSNAILR IDMMCDGVEDLR MIYQEYDTGKDQYI DLPNHLDKFEAVMAK IKAFLGSDAYK FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR |

MGPYTITYFGVR IMMADQGQEWK EILMDFADWTK GDLKASCVFGQLPKFEDGG LVLYQSNAILR IDMMCDGVEDLR MIYQEYDTGKDQYI DLPNHLDKFEAVMAK IKAFLGSDAYK FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR |

pi | sockeye salmon (AB026119) |

| 3 | MGPYTITYFGVR IDMMCDGVEDLR FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR LPINGNGKPVIILNKEG MIYQEVDTGKDQYIK |

MGPYTITYFGVR IDMMCDGVEDLR FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR LPINGNGKPVIILNKEG MIYQEVDTGKDQYIK |

pi | sockeye salmon (AB026119) |

| 4 | MGPYTITYFGVR EILMDFADWTK ASCVFGQLPKFEDGG FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR IDMMCDGVEDLRLK DLPNHLDKFEAVMAK AFLGSDAYK MIYQEVDTGKDQYIK |

MGPYTITYFGVR EILMDFADWTK ASCVFGQLPKFEDGG FEDGGLVLYQSNAILR IDMMCDGVEDLRLK DLPNHLDKFEAVMAK AFLGSDAYK MIYQEVDTGKDQYIK |

pi | sockeye salmon (AB026119) |

| 5 |

|

|

pi | sockeye salmon (AB026119) |

| 5 | LGMDFPNLPYLEDGDRK VDILENQAMDFR FYSCGEAPDYDK |

LGMDFPNLPYLEDGDRK VDILENQAMDFR FYSCGEAPDYDK |

mu | zebra fish (BC057526) |

| 6 |

|

|

rho | red sea bream (AB158415) |

| 7 | WLTYFDGR YLPVFEK |

WLTYFDGR YLPVFEK |

alpha alpha | winter flounder (AY156727) red sea bream (AB169570) |

| 8 | AILNYIAGKYNLTGK YLPVFEK IQAFQEQMKALPAISK |

AILNYIAGKYNLTGK YLPVFEK IQAFQEQMKALPAISK |

alpha alpha alpha | chicken (L15386) red sea bream (AB169570) zebrafish(BC060914) |

Non-homologous amino acids are highlighted in grey.

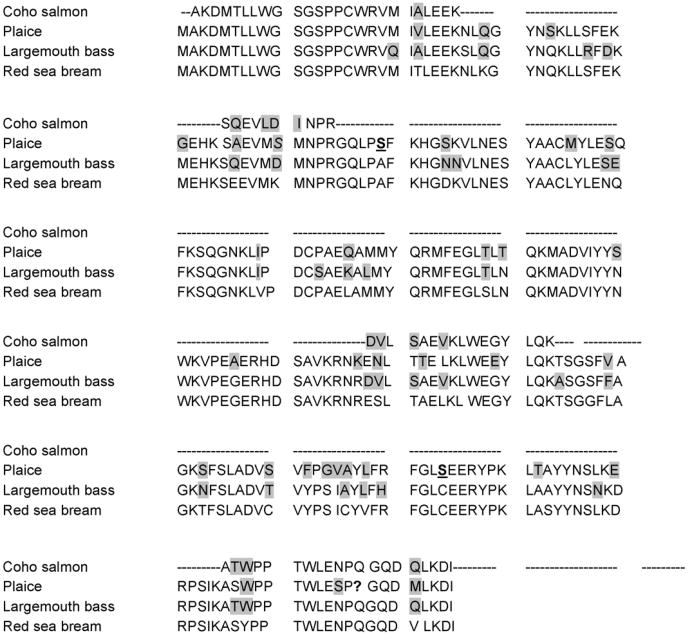

Peptide sequences originating from HPLC peak 6 were homologous to GST-rho in red sea bream (NCBI AB158415, Table 2). These peptide sequences covered 31% of the red sea bream GST-rho protein sequence and displayed 81% homology over this coverage (Table 2). Presented in Fig. 3 is an alignment of putative coho rho-class GST peptide sequences with homologous sequences from largemouth bass, plaice, and red sea bream. The coho peptide sequences display 96% homology to the largemouth bass GST-rho, and 77% homology to the plaice GST-rho, over the 33% of the protein the peptide sequences covered. N-terminal sequences (Fig. 4) from the first 26 amino acids of the rho-class GST are compared to N-terminal sequences of other GST classes. As observed, the rho-class fish GSTs differ markedly from other fish GST classes in the N-terminal region. As seen in Table 2, peak 7 contained two peptides, the first of which was 100% homologous to GST-alpha in winter flounder (NCBI AY156727) while the second peptide exhibited 100% homology to GST-alpha of red sea bream (NCBI AB158414). Protein coverage for the peak 7 peptide relative to the other fish alpha class GSTs was relatively poor (7%, Table 2). Peak 8 also contained peptides with limited peptide coverage (17%) but was homologous to red sea bream GST-alpha (NCBI AB158414), where homology is 76% over the covered portion of the protein (Table 2). The first peptide sequence presented from peak 8 had two non-conserved amino acids when compared to red sea bream, but showed 100% homology to GST-alpha in chicken (NCBI L15386, Table 2). The third peptide from peak 8 had 44% homology to red sea bream GST-alpha and 100% homology to zebra fish GST-alpha (NCBI BC060914). These data indicated that HPLC peaks seven and eight were comprised of alpha-like GSTs. However, the limited MS coverage of peaks 7 and 8 precluded identifying if these peaks consisted of different alpha class isoforms. As observed in Fig. 2A, the relative abundance of the various GST isoforms based on area under the curve (AUC) calculations indicated that the pi and rho-class GSTs were the major isoforms in coho liver, whereas alpha and mu-like GSTs appeared to constitute minor GST isoforms.

Fig. 3.

Putative coho rho-class GST sequence when aligned with GST-rho from plaice, largemouth bass, and red sea bream.

Fig.4.

N-terminal sequence comparison of GST-rho with other fish GST classes.

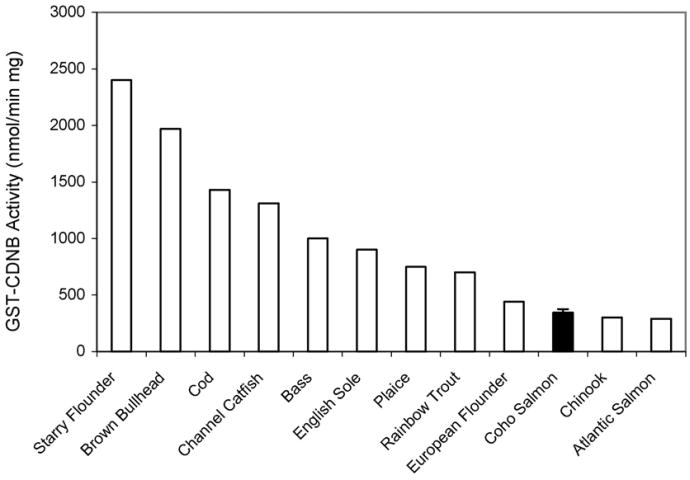

3.4. Catalytic profile of coho hepatic GST

Catalytic activity studies indicated that coho hepatic cytosolic GST was active toward several reference substrates (Table 3). Hepatic GST-CDNB activities, a measurement of overall liver GST activity, were 311 ± 30 nmol/min/mg (Table 3). As observed in Fig. 5, these data indicate a generally low rate of activity in coho liver relative to other fish species. Coho cytosolic fractions also showed GST activity toward ECA (6±0.2 nmol/min/mg) and NBC (25±3.5 nmol/min/mg). In contrast, no detectable activity was observed toward the other reference substrates 4HNE, DCM, NBC, CumOOH, and ADI, as well as toward the pesticides methyl parathion and atrazine.

Table 3. GST catalytic activities in coho liver cytosol.

| Substrate | GST activitya (nmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|

| 1-Chloro-2,4-dintrobenzene | 311(30) |

| Ethacrynic acid | 6 (0.2) |

| 4-Hydroxynonenal | <15b |

| Dichloromethane | <5b |

| Nitrobenzyl chloride | 25 (3.5) |

| Cumene hydroperoxide | <10b |

| 1,2-Dichloro-nitrobenzene | <5b |

| ADI | <5b |

| Methyl parathion | <25b |

| Atrazine | <0.050b |

Data represents mean (S.D.) of assays conducted in triplicate on three composite samples consisting of two coho livers in each sample.

Practical limit of assay detection.

Fig. 5.

Comparative hepatic GST-CDNB activities among fish species.

3.5. GST-CDNB inhibition by bilirubin, atrazine, methyl parathion and chlorpyrifos

Preincubation of coho cytosolic GST with 50 μM bilirubin resulted in a significant 29% loss of hepatic GST-CDNB activity (Table 4). In addition, a minor 12% reduction in the initial rate of GST-CDNB conjugation was observed in the presence of high concentrations (100 μM) of methyl parathion. In contrast, incubation of coho GST in the presence of lower concentrations of methyl parathion, as well as atrazine and chlorpyrifos, did not affect coho cytosolic GST-CDNB activity (Table 4).

Table 4. Inhibition of liver GST-CDNB activity in coho salmon.

| Inhibitor | Inhibitor concentration (μM) | % reduction in GST-CDNB activity |

|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin | 50 | 29 |

| Methyl parathion | 50 | 0 |

| 100 | 12 | |

| Atrazine | 50 | 0 |

| 100 | 0 | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 50 | 0 |

4. Discussion

In the current study, we used a combination of proteomic and biochemical approaches in an attempt to better understand the GST isoforms of coho salmon liver within the context of how coho cope with exposure to environmental chemicals during their life histories. Similar to other salmonids, it appears that a pi-class GST represents a major GST isoform in coho liver. This conclusion is based largely on our observation that peptide sequences from five HPLC peaks collectively covered over 60% of the sockeye salmon GST-pi (AB026119) with virtually 100% homology. Interestingly, the peptide sequence obtained from peak 5, which had slightly less identity to the sockeye GST-pi sequence had a threonine substituted for serine at amino acid position 47, suggesting a polymorphism in this GST isoform. Furthermore, the pi-like sequences obtained from LC–MS analysis of trypsin digested HPLC fractions uniformly exhibited extensive homology when aligned against similar peptides reported for the chinook salmon GST-pi (Donham et al., 2005b). Collectively, our studies and those of others indicate that GST-pi is likely conserved across all salmonid species, and suggest a critical physiological function for the GST-pi protein in salmonids.

The other major GST isoform in coho liver consists of a rho-class GST and member of a relatively newly identified GST class that is unique to fish. A rho-like GST isoform was originally identified by George and co-workers (Leaver et al., 1993) in plaice, who noted that the plaice isoform exhibited unique structural characteristics relative to other GST, but appeared most closely related to the theta GSTs (Leaver et al., 1993). Clustal analysis of GST-rho against class-specific isoforms from other fish is supportive of GST-rho as an evolutionarily distinct branch of GST dissimilar to mammalian class GST, including GST-theta (Konishi et al., 2005). The GST-rho isoform of red sea bream shares over 80% homology with the existing rho-like GSTs of other fish, including GST-A in plaice and largemouth bass, as well as GSTs identified in flounder, gilthead sea bream, and English sole. When GST N-terminal sequences were compared across classes, the rho-class of fish was highly conserved relative to other GST classes. Our further analysis also suggested that a chinook salmon GST originally designated as “theta-like” isoform by Donham based on homology to plaice GST-A (Donham et al., 2005b) was likely a rho-class GST.

In terms of catalytic activities, GST-rho isolated from red sea bream exhibits activity toward the reference substrate CDNB, but has no detectable activity toward ECA, CumOOH, CDNB, 4HNE, or NBC (Konishi et al., 2005). In contrast, the rho-like GSTs isolated from largemouth bass (Doi etal., 2004) and plaice (Leaver et al., 1993) both have a relatively high activity toward 4HNE and are postulated to play a predominant role in protecting against oxidative stress. Thus, it is likely that subtle amino acid differences may markedly affect catalytic activities of rho-class GST in fish. Accordingly, it may be that coho GST-rho is more related functionally to that of sea bream. It is also worth noting that recGST-rho activity in red sea bream and largemouth bass are labile. Given the low coho GST-4HNE and GST-CDNB activities compared to other fish species, it is possible that coho salmon GST is also somewhat labile. However, we were unable to detect GST-4HNE activity in the subsequent reanalysis of freshly prepared coho liver cytosol (data not shown).

In addition to the two major GST isoforms identified in coho liver, other minor coho GST isoforms appear to consist of alpha and mu-like sequences. Although the coho peptide sequence coverage of GST-alpha peaks was limited, the peptides analyzed exhibited over 80% identity to GST-alpha proteins identified in redsea bream, rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus), winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) and zebra fish. Similarly, our data also suggested that a mu-class isoform was a minor GST expressed in coho liver. As noted, however, it is GST catalytic function that is relevant to the detoxification of endogenous and exogenous compounds. In this regard, it is interesting to note that coho salmon liver GST-CDNB activity was low compared to many other fish species, and that liver GST-CDNB activities are relatively similar among coho, chinook, and Atlantic salmon. These data suggest that the overall GST catalytic capacity of coho and other salmonids is relatively low when compared to other fish species. The presence of detectable, albeit low coho liver GST-ECA activity (6 nmol/min/mg) relative to chinook salmon (60 nmol/min/mg) (Donham et al., 2005b) is interesting and may be reflective of an even more limited ability of coho to conjugate GST substrates relevant to chinook. Alternatively, the marked differences observed in GST-ECA activities among coho and chinook may have been a result of inter-laboratory variation in GST-ECA enzymatic rate measurements.

The limitations of using class-specific reference substrates to assign GST isozyme classes based upon catalytic activities in fish were reflected in the present study. Although the presence of coho liver GST activity toward NBC was consistent with expression of a mu-like GST, NBC can also be a substrate for rat theta rGSTT1-1 (Hayes and Pulford, 1995). In the current study, however, we did not identify any theta-like isozymes in coho liver. Additionally, the lack of detectable coho liver GST activity toward DCM, a prototypical GST-theta substrate, was consistent with the absence of a theta-like GST and suggested that the observed GST-NBC activity may have originated from a mu-class GST. The lack of detectable coho liver GST activity towards ADI, a GST-alpha substrate in rats (rGSTA1-2) and humans (hGSTA1-1) (Hayes and Pulford, 1995), was inconsistent with the presence of an alpha class GST by LC/MS. It may be that coho GST-alpha does not catalyze the ADI isomerization reaction and may not be active in steroid metabolism. Studies directed toward the cloning, expression, and catalytic analysis of recombinant coho GST isoforms are needed to provide definitive assignments of substrate specificities for each isoform.

Differences among specificities of GST classes among mammals and fish with respect to chemical conjugation were also observed in the present study. For example, the mammalian pi-class GSTs are generally known to be active toward a number of pesticides and PAH intermediates. Atrazine, a pesticide shown to cause chemical injury to salmon (Moore and Lower, 2001), is a substrate for mouse mGSTP1-1 and human hGSTP1-1 (Abel et al., 2004b). The lack of detectable coho GST activity towards atrazine, despite the expression of coho liver GST-pi, may have resulted from the divergence of GST-pi in fish leading to loss of catalytic activity toward this substrate. Of interest would be the examination of the ability of coho liver GST to detoxify benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide (BPDE), a GST-pi substrate in other species (Robertson et al., 1986), including channel catfish (Gallagher et al., 1996). Additionally, coho liver showed no activity toward methyl parathion, despite the expression of alpha- and mu-like GSTs which catalyze the conjugation of this substrate in rats (rGSTA5-5), mice (mGSTA3-3), and humans (hGSTA1-1, hGSTM1-1) (Abel et al., 2004a).

Our studies also indicated that coho salmon hepatic GSTs may not be major contributors toward protecting against cellular oxidative injury. This hypothesis is based on the lack of detectable cytosolic GST-4HNE conjugating activity or GST peroxidase activity in coho liver. However, the fact that detectable GST-4HNE activity was detected in the affinity-purified GST fraction suggests that coho do have some a limited capacity to detoxify 4HNE via GSH conjugation. Furthermore, we did not analyze the ability of coho liver cytosolic GST to detoxify other α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Also of note is a recent report from our laboratory which indicated that in human liver, the mitochondria are a preferential location of GST isoforms involved in protection against oxidative stress (Gallagher et al., 2006). It would be of interest to determine whether there is conservation of mitochondrial GST isoforms in coho salmon.

In addition to detoxification, certain GSTs such as the alpha class GST isoforms in humans (hGSTA1-1) (Zucker et al., 1995) and rats (rGSTA1-1, rGSTA3-3) (Sheehan and Mantle, 1984), as well as human pi-class GST (hGSTP1-1) (Caccuri et al., 1990; Kaplowitz, 1980; Oakley et al., 1999) exhibit ligandin properties by binding and sequestering endogenous and exogenous compounds (Hayes and Pulford, 1995; Singer and Litwack, 1971; Tipping and Ketterer, 1981; Tipping et al., 1976). Ligandin substrates can include toxicants such as reactive metabolites formed from carcinogens (Arias et al., 1980; Kirsch et al., 1975) as well as endogenous compounds such as heme and bilirubin (da Silva Vaz et al., 2004; Di Ilio et al., 1995; Litwack et al., 1971). It has been hypothesized that the ligandin activity of GST may protect against DNA adduct formation by carcinogens (Hayes and Pulford, 1995), as well as regulate the transfer of endogenous compounds such as bilirubin and other ligands from the plasma into the liver (Arias et al., 1980; Litwack et al., 1971). In the present study, the inhibition of coho GST-CDNB activity by bilirubin suggested that coho GST possess ligandin activity and play a role in sequestering and transporting this endogenous compound. We also extended our GST inhibition studies to include a limited analysis of the ability of two common pesticide non-GST substrates to inhibit coho liver GST activity. However, the lack of significant GST-CDNB inhibition by atrazine and chlorpyrifos, and the minor GST inhibition at high concentrations of methyl parathion indicate that coho liver GST may have limited sensitivity to pesticide-mediated inhibition.

In summary, the results of our studies indicate that coho salmon express a complex GST profile including isoforms representing alpha-, mu-, pi- and rho-class GSTs. Of the various GST isoforms identified, our data indicate that the pi-like and rho-like forms constitute the most highly expressed GSTs in coho liver. Accordingly, future detailed catalytic studies of these two purified or recombinant coho liver GSTs will help us more clearly define the role of hepatic GST in the detoxification of environmental chemicals encountered by salmon. Certainly, the conservation of a pi-like GST in all salmonid species examined to date suggests the conservation of an important physiological function for this enzyme. Although the function of salmon GST-pi has not been established, it could lie in the binding and sequestering of non-GST substrates as opposed to protecting against cellular oxidative stress. Our data, and those of others, also indicate that the recently established GST-rho class extends to Pacific salmon. As with GST-pi, the function of this new class of fish GST is yet to be determined. When interpreted in a broader context, our studies indicate that the relatively low liver overall GST activities in coho and other salmonids may reflect a limited GST detoxification ability relative to other fish. Ultimately, the lack of detectable activity toward pesticides that are GST substrates in other species and poor ability of coho GST to detoxify secondary products of oxidative stress may contribute to this susceptibility of this species to chemical injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Collin White for his technical assistance with the methyl parathion analysis. This work was supported by the University of Washington NIEHS Super-fund Basic Sciences Grant NIEHS P42-004696, the University of Washington NIEHS-sponsored Center for Ecogenetics and Environmental Health (NIEHS P30-ES07033), and by a University of Washington Tools for Transformation Award.

References

- Abel EL, Bammler TK, Eaton DL. Biotransformation of methyl parathion by glutathione S-transferases. Toxicol Sci. 2004a;79:224–232. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel EL, Opp SM, Verlinde CL, Bammler TK, Eaton DL. Characterization of atrazine biotransformation by human and murine glutathione S-transferases. Toxicol Sci. 2004b;80:230–238. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias IM, Ohmi N, Bhargava M, Listowsky I. Ligandin: an adventure in liverland. Mol Cell Biochem. 1980;29:71–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00220301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccuri AM, Aceto A, Piemonte F, Di Ilio C, Rosato N, Federici G. Interaction of hemin with placental glutathione transferase. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier TK, Johnson LL, Meyers MS, Stehr CM, Krahn MM, Stein JE. Fish Injury in the Hylebos Waterway of Commencement Bay. Washington: US Dept of Commerce NMFS-NWFSC-36; 1998. p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Vaz I, Jr, Torino Lermen T, Michelon A, Sanchez Ferreira CA, Joaquim de Freitas DR, Termignoni C, Masuda A. Effect of acaricides on the activity of a Boophilus microplus glutathione S-transferase. Vet Parasitol. 2004;119:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ilio C, Sacchetta P, Iannarelli V, Aceto A. Binding of pesticides to alpha, mu and pi class glutathione transferase. Toxicol Lett. 1995;76:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)03210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi AM, Pham RT, Hughes EM, Barber DS, Gallagher EP. Molecular cloning and characterization of a glutathione S-transferase from largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) liver that is involved in the detoxification of 4-hydroxynonenal. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:2129–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominey RJ, Nimmo IA, Cronshaw AD, Hayes JD. The major glutathione S-transferase in salmonid fish livers is homologous to the mammalian pi-class GST. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1991;100:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(91)90090-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donham RT, Morin D, Jewell WT, Burns SA, Mitchell AE, Lame MW, Segall HJ, Tjeerdema RS. Characterization of glutathione S-transferases in juvenile white sturgeon. Aquat Toxicol. 2005a;71:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donham RT, Morin D, Jewell WT, Lame MW, Segall HJ, Tjeerdema RS. Characterization of cytosolic glutathione S-transferases in juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Aquat Toxicol. 2005b;73:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DL, Bammler TK. Concise review of the glutathione S-transferases and their significance to toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 1999;49:156–164. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/49.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EP, Gardner JL, Barber DS. Several glutathione S-transferase isozymes that protect against oxidative injury are expressed in human liver mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1619–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EP, Sheehy KM, Lame MW, Segall HJ. In vitro kinetics of hepatic glutathione S-transferase conjugation in largemouth bass and brown bullheads. Environ Toxicol. 2000;19:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EP, Stapleton PL, Slone DH, Schlenk D, Eaton DL. Channel catfish glutathione S-transferase isoenzyme activity toward (±)-anti-benzo[a]pyrene-trans-7,8-dihyrodiol-9,10-epoxide. Aquat Toxicol. 1996;34:135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JL, Doi AM, Pham RT, Huisden CM, Gallagher EP. Ontogenic differences in human liver 4-hydroxynonenal detoxification are associated with in vitro injury to fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;191:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SG. Enzymology and molecular biology of phase II xenobiotic-conjugating enzymes in fish. In: Malins DC, Ostrander GK, editors. Aquatic Toxicology: Molecular, Biochemical, and Cellular Perspective. Lewis Publishers; Boca Raton: 1994. pp. 37–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:445–600. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RS, Capel PD, Larson S. Comparison of pesticides in eight U.S. urban streams. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2000;19:2249–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanetich KM, Thumser AE, Phillips SE, Sikakana CN. Reversible inhibition of rat hepatic glutathione S-transferase 1-2 by bilirubin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:1563–1568. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90455-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz N. Physiological significance of glutathione S-transferases. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:G439–G444. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.239.6.G439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RT, Jorgenson JW. Preparation and evaluation of packed capillary liquid chromatography columns with inner diameters from 20 to 50 μm. Anal Chem. 1989;61:1128–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch R, Fleischner G, Kamisaka K, Arias IM. Structural and functional studies of ligandin, a major renal organic anion-binding protein. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:1009–1019. doi: 10.1172/JCI108001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Kato K, Araki T, Shiraki K, Takagi M, Tamaru Y. A new class of glutathione S-transferase from the hepatopancreas of the red sea bream Pagrus major. Biochem J. 2005;388:299–307. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaver MJ, Scott K, George SG. Cloning and characterization of the major hepatic glutathione S-transferase from a marine teleost flatfish, the plaice (Pleuronectes platessa), with structural similarities to plant, insect and mammalian Theta class isoenzymes. Biochem J. 1993;292(Pt. 1):189–195. doi: 10.1042/bj2920189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwack G, Ketterer B, Arias IM. Ligandin: a hepatic protein which binds steroids, bilirubin, carcinogens and a number of exogenous organic anions. Nature. 1971;234:466–467. doi: 10.1038/234466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Lower N. The impact of two pesticides on olfactory-mediated endocrine function in mature male Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) parr. Comp Biochem Physiol B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;129:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa-Valinas MC, Perez-Lopez M, Melgar MJ. Comparative study of the purification and characterization of the cytosolic glutathione S-transferases from two salmonid species: Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) Comp Biochem Physiol C: Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;131:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(02)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley AJ, Lo Bello M, Nuccetelli M, Mazzetti AP, Parker MW. The ligandin (non-substrate) binding site of human Pi class glutathione transferase is located in the electrophile binding site (H-site) J Mol Biol. 1999;291:913–926. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TP. The Behaviour and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout. University of Washington Press; Seattle: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson IG, Guthenberg C, Mannervik B, Jernstrom B. Differences in stereoselectivity and catalytic efficiency of three human glutathione transferases in the conjugation of glutathione with 7 beta,8 alpha-dihydroxy-9 alpha,10 alpha-oxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo(a)pyrene. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2220–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandahl JF, Baldwin DH, Jenkins JJ, Scholz NL. Comparative thresholds for acetylcholinesterase inhibition and behavioral impairment in coho salmon exposed to chlorpyrifos. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2005;24:136–145. doi: 10.1897/04-195r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz NL, Truelove NK, French BL, Berejikian BA, Quinn TP, Casillas E, Collier TK. Diazinon disrupts antipredator and homing behaviours in chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2000;57:1911–1918. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Mantle TJ. Evidence for two forms of ligandin (YaYa dimers of glutathione S-transferase) in rat liver and kidney. Biochem J. 1984;218:893–897. doi: 10.1042/bj2180893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Litwack G. Identity of corticosteroid binder I with the macro-molecule binding 3-methylcholanthrene in liver cytosol in vivo. Cancer Res. 1971;31:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thier R, Pemble SE, Kramer H, Taylor JB, Guengerich FP, Ketterer B. Human glutathione S-transferase T1-1 enhances mutagenicity of 1,2-dibromoethane, dibromomethane and 1,2,3,4-diepoxybutane in Salmonella typhimurium. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:163–166. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipping E, Ketterer B. The influence of soluble binding proteins on lipophile transport and metabolism in hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1981;195:441–452. doi: 10.1042/bj1950441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipping E, Ketterer B, Christodoulides L, Enderby G. The non-covalent binding of small molecules by ligandin. Interactions with steroids and their conjugates, fatty acids, bromosulphophthalein carcinogens, glutathione and related compounds. Eur J Biochem. 1976;67:583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varanasi U, Casillas E, Arkoosh MR, Hom T, Misitano D, Brown DW, Chan SL, Collier TK, McCain BB, Stein JE. Contaminant Exposure and Associated Biological Effects in Juvenile Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) from Urban and Nonurban Estuaries of Puget Sound. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-8 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Wentz DA, Bonn BA, Carpenter KD, Hinkle SR, Janet ML, Rinella FA, Uhrich MA, Waite IR, Laenan A, Bencala KE. Water Quality in the Willamette River Basin, 1991-1995. U S Geological Survey Circular 1161 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Zucker SD, Goessling W, Ransil BJ, Gollan JL. Influence of glutathione S-transferase B (ligandin) on the intermembrane transfer of bilirubin. Implications for the intracellular transport of nonsubstrate ligands in hepatocytes. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1927–1935. doi: 10.1172/JCI118238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]