Abstract

Galectin-1 (GAL1) is an S-type lectin with multiple functions, including the control of B cell homeostasis. GAL1 expression has been reported to be under the control of the plasma cell master regulator BLIMP-1. GAL1 was detected at the protein level in LPS-stimulated B cells and was shown to promote immunoglobulin secretion in vitro. However, the pattern of GAL1 expression and function of GAL1 in B cells in vivo is still unclear. Here we show that among B cells, GAL1 is only expressed by differentiating plasma cells following T-dependent or T-independent immunization. Using GAL1 deficient mice we demonstrate that GAL1 expression is required for the maintenance of antigen-specific immunoglobulin titers and antibody secreting cell numbers. Using an in vitro differentiation assay we find that GAL1 deficient plasmablasts can develop normally but rapidly die, through caspase 8 activation, under serum starvation-induced death conditions. Actually, TUNEL assays show that in vivo generated GAL1 deficient plasma cells present an increased sensitivity to apoptosis. Taken together, our data indicate that endogenous GAL1 supports plasma cell survival and participates in the regulation of the humoral immune response.

Introduction

Galectin 1 (GAL1) is a small lectin belonging to a well-conserved family consisting of 15 members sharing a high affinity for β-galactosides (1). GAL1 consists of a single carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) with a short NH2 sequence and is active as a non-covalently bonded homodimer (2). GAL1 can be found in several cellular compartments including the cytoplasm where it can play multiple roles and in the nucleus where it acts as a splicing factor (3, 4). Although galectins do not have the signal sequence required for protein secretion through the usual secretory pathway (5), some galectins such as GAL1 can be secreted. While the intracellular functions of GAL1 are generally independent of carbohydrate binding, its extracellular activity mostly requires its lectin activity (6).

GAL1 has been showed to be involved in the regulation of immune functions. It acts as a homeostatic agent by modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. Notably, GAL1 has been shown to control T cell homeostasis but also cancer progression (6-8). Under physiological conditions, extracellular GAL1 promotes apoptosis of activated but not resting immune cells (9, 10), with the notable exception of resting T cells, which are sensitized to CD95/Fas mediated cell death by GAL1 (11). GAL1 also induces phosphatidyl-serine externalization without associated apoptosis (12, 13). Moreover, galectins can cross-link glycosylated proteins leading to signal transduction and direct cell death or activation of other signals regulating cell fate (14). Finally, GAL1 secretion was showed to induce death of anti-tumor T cells and thus, might contribute to immune escape by tumors (6, 15).

Although the roles of GAL1 in control of immune responses, inflammation and tumor progression have been well characterized, very little is known about its expression and function in B lymphocytes. We demonstrated that GAL1 is important for early B cell differentiation in the bone marrow (16). In this case, GAL1 secreted by bone marrow stromal cells supports B cell differentiation through pre-BCR activation and signaling (16, 17). Further, using an in vitro model of LPS activated B cells, Tsai et al. (18), reported that splenic plasmablasts expressed GAL1 in a Blimp-1 dependent manner. They also showed that ectopic expression of GAL1 in mature B cells increased immunoglobulin (Ig) transcripts and secretion.

To further study the role of GAL1 in vivo, we followed GAL1 expression and the immune responses of wild type and GAL1 knockout mice (Lgals1−/−). We showed that among B cells GAL1 is specifically expressed by plasma cells and more precisely by Blimp1-GFPlow plasma cells that are not fully differentiated. Moreover, Lgals1−/− mice can initiate a normal immune response but fail to maintain serum immunoglobulin levels and antibody secreting cell numbers. Finally, we reported that GAL1 deficient plasmablasts are more susceptible to apoptosis than their normal counterparts.

These findings provide new insights into how GAL1 modulates the immune response and emphasize the regulatory role of GAL1 in finely tuning biological processes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

GAL1-deficient mice (19), backcrossed for 6 generations onto a 129SV background, and 129SV control mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and handled in accordance with European directives, with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Inserm/CNRS. Mice were immunized by 2 intraperitoneal injections (separated by 2 weeks) of 100μg NP(30)-KLH (Biosearch technologies) with Alum 1v:1v (Pierce) for T-dependent responses and by 1 intraperitoneal injection of 1μg NP(40)-Ficoll (Biosearch technologies) in PBS for T-independent responses. Blood samples were harvested and Ab responses analyzed by ELISA at the indicated time points after immunizations.

C57BL/6 Blimpgfp mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. They were immunized with 100μg NP(30)KLH in Alum intraperitoneally and analyzed 2 weeks later. All experiments were performed according to the regulations of the UK Home Office Scientific Procedures Act (1986).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were stained using standard protocols for flow cytometry using the antibodies listed in Table I. Intracellular staining was performed after fixation and cell permeabilization using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, Pont de Claix, France). Alternatively, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and permeabilized with PBS/0.2% saponin to allow co-detection of GFP and intracellular GAL1. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on a FACSCantoII, LSRII (BD Biosciences) or CyAn (DAKO) apparatus. Data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar) or DiVa (BD Biosciences) softwares.

Table I.

Antibodies for flow cytometry

| Reactivity | Source | Clone | Conjugate | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary mAb | ||||

| Mouse B220 | Rat | RA3-6B2 | FITC | eBioscience |

| Mouse B220 | Rat | RA3-6B2 | Pacific blue | eBioscience |

| Mouse CD21 | Rat | 7G6 | APC | BD Biosciences |

| Mouse CD23 | Rat | B3B4 | PE-Cy7 | eBioscience |

| Mouse CD93 | Rat | AA4.1 | PE | eBioscience |

| Mouse CD138 | Rat | 281-2 | biotin | BD Pharmingen |

| Mouse Galectin 1 | Rat | 201002 | Alexa 647*, Alexa 546* | R&D |

| Mouse Gl7 | Gl7 | biotin | eBioscience | |

| Mouse IgM | Rat | II/41 | PE-Cy5.5 | eBioscience |

| Streptavidin | PE-Cy5 | eBioscience | ||

| Streptavidin | APC-Cy7 | eBioscience |

Conjugated in our laboratory using the antibody labeling kit from Molecular Probes.

In vitro plasma cell differentiation

Splenic B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were isolated using B220 microbeads and the autoMACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France). Cells (1×106) were cultivated in IMDM, 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. When specified, cultures were also performed in 5% FCS. Cells were stimulated with 1μg/ml LPS during 4 days (Sigma). Plasma cell differentiation was also tested using 1μg/ml NP-Ficoll (Biosearch technologies) or using 5 μg anti-IgM (Sigma Aldrich) and 1ng/ml CD40L (Abcys) and 25ng/ml IL-4 (R&D systems).

ELISA

Serum of immunized or control mice was obtained after blood coagulation and kept at −20°c. 96-well plates (Nunc) were coated with 5 μg/ml of NP(23)-BSA to detect low and high affinity antibodies or of NP(3)-BSA (Biosearch technologies) to detect only high affinity antibodies, overnight at 4°C. Ig concentrations in culture supernatants were quantified using the Clonotyping System-AP (Southern Biotech). In brief, plates were coated with 5 μg/ml of anti-Ig (H+L) overnight at 4°C and then saturated with PBS-BSA 2%. Standard mouse Ig (Southern Biotech) or samples were then added to the wells at different dilutions. After extensive washing in PBST (PBS and 0.05% tween20), anti-mouse Ig subclasses coupled with alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotech) were added to the wells and revealed by alkaline phosphatase substrate (Sigma). NaOH 3M was used to quench color development and O.D. was measured at 405 nm and referred to plate background at 620nm. Ig concentrations were calculated by comparison to each Ig subclasses standard curves.

ELISPOT

MultiScreen HTS-IP filter plates (Milllipore) were coated with 5μg/ml of NP(23)-BSA to detect low and high affinity antibodies or with 5μg/ml of NP(3)-BSA (Biosearch technologies) to detect only high affinity antibodies, overnight at 4°c. Alternatively, plates were coated with 5μg/ml of goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) for detection of in vitro generated ASC. Plates were then washed with double-distilled water and saturated with MEMα medium supplemented with 10% FCS. The number of viable cells was evaluated by trypan blue exclusion and the indicated number of live cells (105 splenic and 106 bone marrow cells, and 103-104 cells from in vitro cultures) was carefully plated in each well. The number of ASC was analyzed after 16h at 37°c. Cells were harvested and plates washed 3 times in PBS, 3 times in PBST and twice in double-distilled water. Goat anti-mouse Ig subclasses antibodies labeled to alkaline phosphatase were added to the wells for 1h (SBA-Clonotyping System-AP, Southern Biotech). After extensive washing in PBST, Alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate (Biorad kit) was added and incubated at 37°c for 30 min. Reaction was stopped by PBS and then water and plates were air-dried. Plates were read using an AID ELISPOT reader according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistofluorescence

Spleens were snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek). Frozen sections (7 μm) were fixed with cold acetone for 2 min. Unspecific binding site blockade was performed with 2% bovine serum albumin and 1% donkey serum in PBS for 1h and permeabilization was achieved by incubation with 0.1% triton X100 and 0.05% tween20 in PBS, at room temperature for 1h. Femurs were first fixed in formalin for 48 hours, and then decalcified in PBS/10% EDTA for 20 days. Following decalcification, bones were dehydrated in PBS/30% sucrose for 48 hours, then embedded in OCT (RA Lamb, UK) and snap-frozen in isopentane on dry ice before 20 μm sections were cut using a cryostat. Sections were fixed and permeabilized in saturation buffer (2% bovine serum albumin, 1% horse serum, 0.05% Tween20, 0.1% triton-X100 in PBS) for 1h at room temperature. Sections were labeled overnight at 4°C with an anti-galectin1 antibody (clone 201002, R&D), then incubated for 1h at room temperature with an anti-rat biotinylated antibody and revealed with streptavidin coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 or AlexaFluor 647 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Sections were also labeled using anti-mouse IgM coupled to Phycoerythrin (PE), anti-mouse IgG coupled to FITC or AlexaFluor 568 and NP-PE during 1h at room temperature. TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was used to stain nuclei. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM510 microscope and image processing with Zeiss LSM software.

RNA extraction, RT and Q-PCR

RNA was extracted from total cells in culture with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). One μg RNA was converted into cDNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real time PCR was performed with 100 ng of cDNA using the Sybr green PCR master mix (Applied biosystems). Each sample was run in triplicate in a PCR System (ABI PRISM 7500; Applied Biosystems). Primers were designed on two different exons for each gene of interest and a blast was performed to attest amplicon specificity. At the end of the PCR, specificity of the amplification was controlled by generating a melting curve of the PCR product. Expression values were normalized using the HPRT housekeeping gene, run on the same plate. The results were analyzed according to the ΔΔCt comparative method, normalizing to 1 for WT expression at day 0.

Primers used: HPRT forward 5′-GGCCCTCTGTGTGCTCAAG-3′ reverse 5′-CTGATAAAATCTACAGTCATAGGAATGGA-3′ GAL1forward 5′-CCTGGTCCATCTTCACTTCCAT-3′ reverse 5′-CTTTGGCCTGGAAAGCACAA-3′

Apoptosis assays

Membrane permeabilization was evaluated using 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Mitochondrial potential and phosphatidyl serine externalization were evaluated using Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Apoptosis Kit with Mitotracker™ Red and Annexin V Alexa Fluor® 488 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Caspase 8 activation was quantified with CaspaseGlow Fluorescein Active Caspase 8 Staining kit (Biovision, Clinisciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

TUNEL assays

TUNEL assays were performed using the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, frozen sections were fixed with 4% PFA and rinsed twice in PBS. Samples were then permeabilized 5 min with 0.2% triton X100, and washed with PBS. The slides were covered with Equilibration Buffer during 5 min and incubated with the reaction buffer (45μl Equilibration Buffer + 5μl Nucleotide Mix + 1μl rTDT Enzyme) during 1H at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by immersing the slides in 2X SSC for 15 minutes at room temperature. The number of TUNEL+ plasma cells per field was enumerated with the Volocity 3D Image analysis software (Perkin Elmer).

Proliferation assays

Splenic B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were isolated using B220 microbeads and the autoMACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France). Cells (1.5 ×105) were plated in complete IMDM in the presence of 5 or 10% FCS in 96-well plates and then stimulated with 1μg/ml LPS. Two and three days after plating, 1μl of 3H thymidine was added in each well during 12h. Plates were directly frozen and analyzed using a Beta Counter (Wallac Trilux).

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically evaluated using the Mann-Whitney unpaired test with a risk of 5%. Differences were considered statistically different (indicated by an asterisk in the Figures) if the p-value was less than 0.05. Error bars represent SEM.

Results

Galectin 1 is expressed by plasmablasts

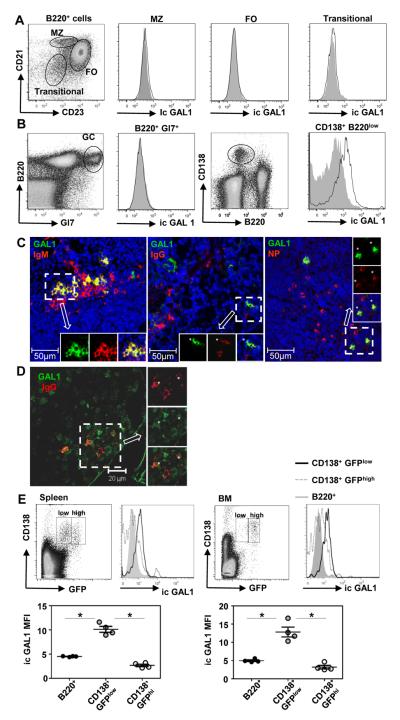

We first analyzed GAL1 expression in splenic B cell sub-populations in non-immunized and immunized mice by flow cytometry. At steady state in non-immunized mice we observed that follicular (B220+CD21+CD23high), marginal zone (B220+CD21highCD23low) and early transitional (B220+CD21−CD23−) B cells do not express detectable levels of GAL1 (Figure 1A). After T-dependent immunization with NP-KLH, follicular, marginal zone, transitional but also germinal center (B220+Gl7+) B cells were found negative for GAL1 expression (Figure 1 B and data not shown). In contrast, B220lowCD138+ plasma cells (PCs) are GAL1+ (Figure 1B) and GAL1 expression was also detected in B220lowCD138+ plasma cells after T-independent responses against NP-Ficoll (Supplementary data 1). Among splenic B cell sub-populations, only CD138+ plasma cells express GAL1 and this expression is detected after primary and secondary immune responses, and at least until day 40 post-immunization (Supplementary data 2A and B).

Figure 1. GAL1 is expressed by plasmablasts.

Spleen cells from non-immunized mice (A) and mice immunized with a T-dependent antigen (NP-KLH) at day 21 (B) were stained for cell surface expression of B220, CD21, CD23, GL7 and CD138 and for intra-cytoplasmic expression of GAL1 and analyzed by flow cytometry. B220+CD21+CD23high follicular (FO), B220+CD21highCD23low marginal zone (MZ), B220+CD21−CD23− early transitional and B220+GL7+ germinal center (GC) B cells and B220lowCD138+ plasma cells (PC) are indicated. Cells from Lgals1−/− mice were similarly stained and used as negative controls for GAL1 expression. Histograms for Lgals1−/− and WT mice are filled in grey and white, respectively. Data are representative of more than 5 independent experiments with at least 4 mice per group. (C) Immunohistofluorescence was done on spleen sections of mice immunized with a T-independent antigen (NP-Ficoll), 7 days after injection. Anti-GAL1, anti-IgM, anti IgG and NP-PE staining were also performed. A representative extra-follicular zone (low nuclei density) of the spleen is shown. Images are representative of more than 5 different fields from 5 immunized mice. GAL1 is in green, IgM, IgG and NP in red and nuclei in blue (D) Immunohistofluorescence was done on bone marrow sections of mice immunized with a T-dependent Ag (NP-KLH), 8 days after the secondary injection. Anti-GAL1 and anti-IgG staining were performed and a representative field of the bone marrow is shown. GAL1 is in green and IgG in red. Asterisks show double-stained cells. The image is representative of 3 different fields from 2 immunized mice. (E) Spleen (left top panel) and bone marrow (right top panel) cells from NP-KLH immunized Blimp1gfp mice at day 15, were stained with anti-GAL1, anti-CD138 and anti-B220. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of GAL1 staining for B cells (B220+), PBs (CD138+GFPlow) and fully differentiated PCs (CD138+GFPhigh) in the spleen (left lower panel) and bone marrow (right lower panel) are shown. The legend of the histograms is indicated on the Figure. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice per group.

* indicates significance between conditions with p<0.05.

To visualize GAL1 expressing cells in situ, immunohistofluorescence was performed on spleen sections from immunized mice. As shown in Figure 1C after a T-independent response, a fraction of IgM+, IgG1+ and NP-specific cells express GAL1. These cells are localized in the extra-follicular regions of the spleen, as conventional PCs usually are. We also observed expression of GAL1 by some but not all PC in the bone marrow (BM) seven days after secondary immunization with NP-KLH (Figure 1D).

To assess whether GAL1 was expressed at all stages of plasma cell differentiation, we used the Blimp1gfp reporter mice (20). These mice express the GFP reporter under the control of the Blimp1 promoter and allow the discrimination of CD138+GFPlow plasmablasts (PBs) from CD138+GFPhigh fully differentiated plasma cells. Fourteen days after NP-KLH T-dependent immunization we observed that CD138+GFPlow PBs, in the spleen and in the bone marrow, express higher level of GAL1 when compared to B220+ cells (Figure 1E). Interestingly, the MFI values for GAL1 expression were reduced on splenic and BM CD138+GFPhigh PCs, suggesting that GAL1 is transiently expressed by plasmablasts before being down-regulated in fully differentiated plasma cells.

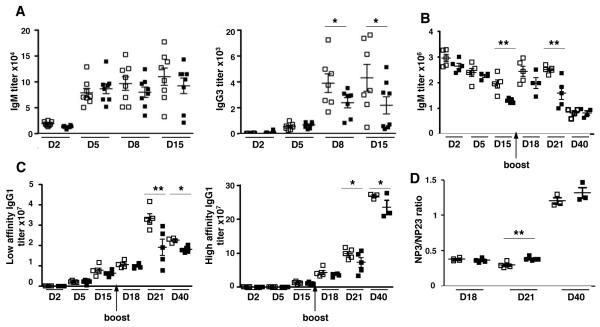

Serum immunoglobulin levels are decreased in GAL1 deficient mice

We then tested the impact of GAL1 expression on humoral immune responses. Following T-independent immunization, we observed a significant reduction in the serum titer of NP-specific IgG3 at day 8 and 15 in Lgals1−/− mice compared to wild type (WT) mice (Figure 2A). Although not statistically significant, we also observed a trend towards lower NP-specific IgM titer in the GAL1 deficient mice compared to WT. After T-dependent immunization, the kinetic of NP-specific IgM and IgG1 formation in Lgals1−/− mice parallels that of WT mice (Figure 2B and 2C). However, in the absence of GAL1, IgM titers at days 15 and 21 (Figure 2B) and low and high affinity IgG1 titers at days 21 and 40 (Figure 2C) were significantly reduced. The NP3 (high)/NP23 (low) IgG1 affinity ratio was the same for WT and Lgals1−/− immunized mice, except at day 21 where it was slightly increased in Lgals1−/− mice (Figure 2D). This increased ratio at day 21 could be explained by the fact that affinity antibody titer would be affected before that of high affinity antibodies. Thus, GAL1 does not appear to play a role in the initiation of the immune response but seems to be important for the maintenance of antigen-specific Ig titers after boost, without affecting Ig affinity maturation.

Figure 2. Serum immunoglobulin levels are decreased in immunized Lgals1−/− mice.

WT and Lgals1−/− mice were immunized with NP-Ficoll (T-independent antigen), 7 mice for each group (A) and with NP-KLH in alum (T-dependent antigen), 5 mice for each group (B, C) and Ig secretion in serum was quantified by ELISA. NP-specific IgM and IgG3 levels were determined at D2, D5, D8 and D15 for the T-independent responses (A). NP-specific IgM (B), low (NP23) and high (NP3) NP-specific IgG1 serum titers (C) were analyzed at D2, D5, D15, D18, and D21 for T-dependent responses. (D) Affinity maturation of T-dependent immune responses at days 18 and 21 was measured by the NP3 (high) / NP23 (low) affinity IgG1 ratio. Open and black squares correspond to WT and Lgals1−/− mice, respectively.

* and ** indicate significance versus WT mice with p<0.05 and <0.005 respectively.

Altogether, our results indicate that Lgals1−/− mice normally initiate immune responses after T-independent and T-dependent immunizations but failed to maintain high titers of NP-specific immunoglobulins at later time points.

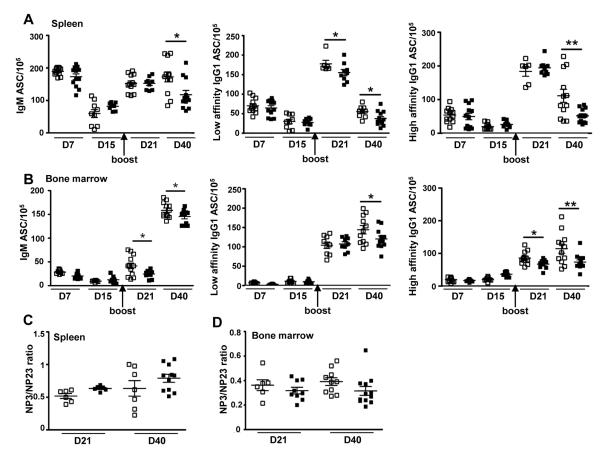

Antigen-specific plasma cell numbers are altered in GAL1 deficient mice

To determine whether the reduction in NP-specific Ig titers in Lgals1−/− mice was due to a defect in plasmablast/plasma cell formation, we monitored by ELISPOT the number of NP-specific antibody secreting cells (ASCs) generated following T-dependent immunization. Total splenic and BM cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were plated and cultured for 16h on NP-coated ELISPOT plates, and the number of IgM, low and high affinity IgG1 ASC was determined. As shown in Figure 3A, the numbers of IgM and IgG1 NP-specific ASC generated in the spleens of Lgals1−/− mice were initially normal but were then significantly decreased at day 40 when compared to WT mice. At day 21, low affinity IgG1 ASC were also significantly decreased in GAL1 deficient mice. For Lgals1−/− BM derived ASC, a decrease in IgM, and low and high affinity IgG1was noted at day 40 but also at earlier time points for IgM and high affinity IgG1 ASC (Figure 3B). However, affinity maturation as measured by the NP3 (high)/NP23 (low) ratio was not modified in absence of GAL1 in the spleen (Figure 3C) and in the BM (Figure 3D), at day 21 and 40. Interestingly, spot intensities were similar in WT and Lgals1−/− cultures at any time tested (data not shown), suggesting a correct secretion process for Lgals1−/− plasma cells.

Figure 3. In vivo generated plasma cells are altered in Lgals1−/− mice.

WT and Lgals1−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH in alum. The numbers of NP-specific IgM and IgG1 ASC in the spleen (A) and bone marrow (B) of WT and Lgals1−/− mice were evaluated by ELISPOT. Studies were performed in triplicate with at least 5 mice per group. Affinity maturation was measured by the NP3 (high)/NP23 (low) affinity ASC ratio in spleen (C) and in bone marrow (D) at day 21 and day 40. Data are means of 2 independent experiments with 4 mice per group. Open and black squares correspond to WT and Lgals1−/− mice, respectively.

* and ** indicate significance versus WT mice with p<0.05 and <0.005 respectively.

Altogether, these data indicate that plasma cells are correctly generated in the spleen of Lgals1−/− mice after T dependent immunization but their number decrease in spleen and BM at late time points of the immune response. The impairment in sustaining plasma cells following immunization could explain the defect in NP-specific Ig titers and ASC observed in these mice.

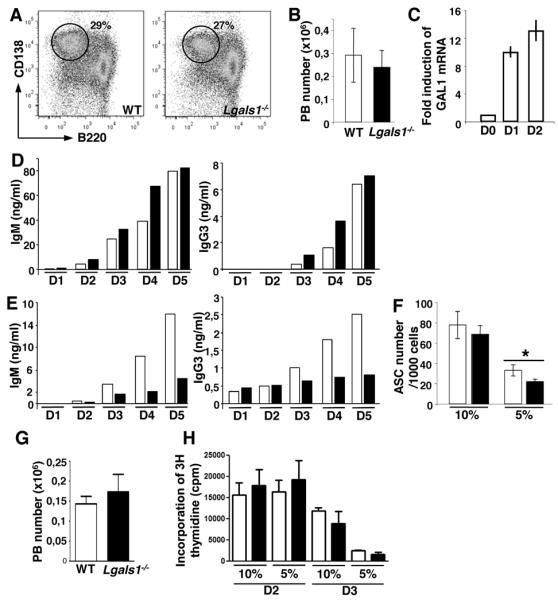

In vitro generation of antibody secreting cells is altered in the absence of GAL1

In order to dissect the role of GAL1 in plasma cell numbers and Ig secretion, we developed an in vitro assay where plasma cell differentiation was challenged. Splenic B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were activated using various stimuli during 4 days and the generation of CD138+ plasmablasts was followed by flow cytometry. After LPS stimulation, the same percentage (25-30%) and total cell number (2-3 ×105) of CD138+ cells were generated from WT and Lgals1−/− B cells (Figure 4 A and B). Similar results were obtained after NP-Ficoll or anti-IgM plus CD40L plus IL-4 stimulations (data not shown). We showed by Q-PCR that GAL1 mRNA was faintly expressed in non-stimulated WT B cells but was up regulated in the first days of LPS-induced differentiation (Figure 4C). Ig secretion in LPS-stimulated B cell supernatants was monitored by ELISA at different time points. During differentiation, an increase in IgM (from day 2) and IgG3 (from day 3) levels was observed both for WT and Lgals1−/− B cell cultures (Figure 4D). However, when the same experiments were performed in limiting culture conditions, i.e. by decreasing FCS concentration from 10% to 5%, IgM and IgG3 concentrations were reduced in Lgals1−/− compared to WT B cell culture supernatant (Figure 4E). The number of ASC generated from LPS-stimulated B220+ splenic B was quantified by ELISPOT. Stimulated B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were cultured in medium containing 10% or 5% FCS, and after 3 days, viable cells were counted and plated with the same FCS concentration on ELISPOT plates. When culture media were supplemented with 10% FCS, no difference in the number of ASC was observed between WT and Lgals1−/− cultures, whereas a reduced number of ASC was noted in 5% FCS condition for Lgals1−/− derived-plasmablasts (Figure 4F). This decreased number of ASCs generated from Lgals1−/− cells was not due to compromised cell differentiation or proliferation at low serum concentration. Indeed, the number of CD138+ cells generated after 4 days of LPS stimulation in the presence of 5% FCS was the same in WT and Lgals1−/− cultures (Figure 4G). Moreover, there was no difference in the proliferation rate, assessed by 3H thymidine incorporation at day 2 and 3, for WT and Lgals1−/− cells cultured in presence of 10% or 5% FCS (Figure 4H). Thus, decreasing FCS concentration in culture medium after stimulation of Lgals1−/− B cells reveals a defect in ASC number, which does not affect cell differentiation/proliferation, and a decrease in Ig concentration in culture supernatants.

Figure 4. Immunoglobulin levels are decreased in in vitro generated Lgals1−/− plasmablasts.

B220+ splenic B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were enriched by magnetic selection and cultured during 4 days in the presence of 1μg/ml of LPS in complete RPMI medium with 10% FCS. The percentage (A) and the absolute cell number (B) of B220lowCD138+ PB generated from 106 B220+ spleen cells 4 days after stimulation were evaluated by flow cytometry. (C) GAL1 expression in non-stimulated and in LPS-stimulated B cells was determined by Q-PCR at days 1 and 2 after stimulation. (D, E) IgM and IgG3 secretion in culture supernatants from WT and Lgals1−/− cells were quantified by ELISA. Cultures were performed in culture medium supplemented with 10% (D) or 5% (E) FCS and cells were allowed to secrete Ig for 16h. (F) The number of antibody-secreted cells (ASC) obtained from 1000 viable plated cells after WT and Lgas1−/− cultures performed in 10% and 5% FCS, was determined by ELISPOT. Data are representative of more than 5 independent experiments. (G) Absolute number of B220low CD138+ PB generated from 106 B220+ spleen cells in the presence of 5% FCS and after 4 days of LPS stimulation. (H) Incorporation of 3H thymidine at day 2 and 3 (evaluated in cpm) by LPS stimulated B220+ cells in the presence of 10% and 5% FCS. Open and black squares correspond to WT and Lgals1−/− mice, respectively.

* indicates significance versus WT mice with p<0.05.

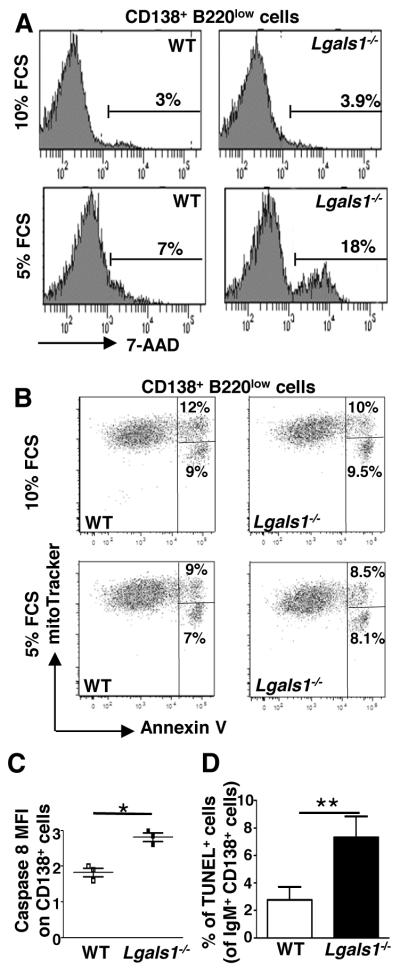

Plasmablasts from GAL1 deficient mice are more susceptible to apoptosis

We first evaluated the sensitivity to apoptosis of the in vitro generated Lgals1−/− PBs. When cultures were performed with 10% FCS, the percentage of CD138+7-AAD+ cells was the same in WT and Lgals1−/−-derived PBs and represent 3-4% of the cells (Figure 5A). In contrast, decreasing FCS to 5% increased the frequency of 7-AAD+ PBs up to 7% in WT cultures but up to 18% in Lgals1−/− cultures, i.e. 2.5 times more than in WT cultures (Figure 5A). Thus, in vitro generated PBs deficient for GAL1 display a higher susceptibility to cell death under serum starvation-induced death conditions. In order to further dissect this phenomenon we tested different mechanisms of apoptosis, such as mitochondrial depolarization, phosphatidyl serine externalization and caspase 8 activation. We used mitotracker and annexin V staining to follow mitotrackerhigh/annexinV+ cells, which have just externalized phosphatidyl serine and mitotrackerlow/annexinV+ cells, which present a decreased mitochondrial potential. As shown in Figure 5B, we did not observe any difference in the depolarization potential of the mitochondria or in phosphatidyl serine externalization of WT and Lgals1−/− PBs generated in normal or low FCS concentrations. In contrast, we observed increased caspase 8 activation in Lgals1−/− PBs compared to WT cells (Figure 5C). This phenomenon appears to be plasmablast-specific, as WT and Lgals1−/− B220+CD138− B cells exhibit similar rates of cell death mainly due to mitochondrial depolarization and phosphatidyl serine externalization rather than to caspase 8 activation (Supplementary data 3). Thus, using an in vitro differentiation assay we showed that GAL1 deficient PBs formed normally but rapidly die by apoptosis through caspase 8 activation in serum starvation conditions.

Figure 5. In vitro and in vivo generated Lgals1−/− plasmablasts are more susceptible to apoptosis than WT plasmablasts.

(A-C) B220+ splenic B cells from WT and Lgals1−/− mice were cultured with 1μg/ml LPS during 3 days in complete medium containing 10% or 5% FCS. (A) Quantification of apoptotic B220lowCD138+ plasmablasts was determined by 7-AAD incorporation. (B) Quantification of mitochondrial depolarization and phosphatidyl serine externalization on B220lowCD138+ plasmablasts using mitotracker and annexin V staining. Lived cells are mitotrackerhigh/annexinV−, cells with externalized phosphatidyl serines are mitotrackerhigh/annexinV+ and cells with a decreased mitochondirial potential are mitotrackerlow/annexinV+. (C) Quantification of caspase 8 activation. Fold changes in active caspase 8 MFI in B220lowCD138+ plasmablasts generated in culture medium supplemented with 10% or 5% FCS are represented. Data in A and B are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) WT and Lgals1−/− mice were immunized with NP-KLH in alum (T-dependent Ag), 6 mice for each group, and the percentage of splenic apoptotic cells within IgM+CD138+ cells was quantified using TUNEL assays at day 21. For WT and Lgas1−/− mice 3893 and 2154 cells were counted, respectively.

* and ** indicate significance versus WT mice with p<0.05 and <0.005 respectively.

To strengthen the in vitro results, TUNEL assays were performed to measure the sensitivity to apoptosis of in vivo generated GAL1-deficient PCs. WT and Lgals1−/− mice were immunized with the NP-KLH T-dependent Ag and TUNEL assays were performed on spleen sections at day 21 and day 40 after immunization. We observed that in Lgals1−/− mice the percentage of TUNEL+ cells was higher in IgM+CD138+ PCs cells compared to WT mice, at day 21 (Figure 5D) and at day 40 (data not shown).

Altogether, our results show that GAL1 deficient PCs are more susceptible to apoptosis than their normal counterparts.

Discussion

Many reports have highlighted the crucial role of GAL1 in immunity, inflammation and tumor progression but little was known about its effect on B cells. Here, we showed that GAL1 is specifically expressed by splenic and bone marrow PBs during plasma cell differentiation following T-independent and T-dependent immune responses. This is in accordance with the detection of GAL1 transcripts after Blimp1 transfection of human and mouse B cell lines, or after in vitro LPS stimulation of mouse B cells (18, 21). We also revealed a new role for GAL1 in the maintenance of ASC numbers and Ig titers during T-dependent and T-independent immune response. Using an in vitro differentiation assay we showed that Lgals1−/− PBs are more susceptible than they WT counterparts to serum starvation-induced death conditions. Actually, TUNEL assays show that in vivo generated GAL1 deficient plasma cells present an increased sensitivity to apoptosis. GAL1 does not appear to interfere with affinity maturation and Ig class switching as we observed normal levels of the different Ig isotypes and of high affinity NP-specific IgG1 in Lgals1−/− mice, after immunization. Thus, our results indicate that GAL1 controls the number of PB during the immune response by regulation of caspase 8-mediated apoptosis.

In contrast to our results, Tsai et al. reported that immune responses were not altered in Lgals1−/− mice (18). As they refer to data not shown, we could not compare the antigen, the doses and the immunization protocol used between the two studies. Moreover, it is well known that some phenotypes are strongly dependent on the mouse genetic background (22). Thus, the differences observed could rely to the fact that our experiments are performed on Lgals1−/− mice backcrossed with 129SV mice for a minimum of 6 generations, whereas Tsai et al., used Lgals1−/− mice on a mixed C57Bl6/129SV genetic background, with chimerism markers still present.

Although we observed a significant defect in Ig serum titers and PC numbers in Lgals1−/− mice on pure genetic backgrounds (129SV in this study and C57Bl6, data not shown) we cannot completely rule out that some other galectins may be important for PC homeostasis. Indeed, galectin redundancy was already reported in other biological systems. In line with this, Tsai et al. (23), observed the expression of GAL8 in in vitro LPS-activated B cells. In our in vivo system we confirmed by PCR that GAL8 was also expressed in sorted CD138+ B220low cells obtained from WT mice after T-dependent immunization (data not shown).

In contrast to the well-established pro-apoptotic effect of GAL1 on T cells (8), GAL1 appears to have a protective effect during plasma cell differentiation. Antagonist roles for GAL1 have already been described in the lymphoid lineage. For example, in the thymus, GAL1 is expressed by epithelial cells (24) and induces cell-cycle arrest and/or apoptosis of human and murine thymocytes (9, 25-27). In contrast, in the BM, GAL1 expressed by stromal cells supports B cell differentiation through pre-BCR activation and signaling (16, 17, 28). These activities are both dependent on extracellular GAL1. Recently, secreted GAL1 was found to bind to splenic mature B220+ B cells and not to CD138+ B220low cells (18). This is due to the differential expression of glycosyl transferases by the two cell types, which results in the expression of specific cell surface glycans (23). Taking into account these results we postulate that the anti-apoptotic effect of GAL1 on CD138+B220low cells is not dependent on GAL1 secretion by PC that do not possess the mandatory glycosylations to bind it, but is rather due to intracellular mechanisms. Nevertheless, in vivo, an extrinsic role of GAL1 cannot be excluded since GAL1+ dendritic cells, resident and inflammatory macrophages are present in the spleen and in lymph nodes (unpublished data), and may influence immune responses, especially PC differentiation. Moreover, GAL1 was shown to be expressed by bone marrow stromal cells and could influence PC homing and survival in this organ (17). However, our in vitro experiments were performed using purified B220+ B cells in absence of exogenous recombinant GAL1 in the cultures supporting a cell autonomous effect of GAL1 on the newly generated plasmablasts.

Because only few CD138+ cells are generated in vivo and because these cells are extremely sensitive to apoptosis during cell sorting, we used in vitro studies to determine whether the pro-apoptotic signaling pathways were overstimulated in GAL1 deficient mice. While the apoptosis was not associated to mitochondria depolarization, we observed an increase in caspase 8 activation. Caspase 8 was shown to be activated by FADD (FAS-associated protein with death domain) which is the main adaptor protein transmitting apoptotic signals mediated by death receptors like FAS, TNF receptors or TRAIL receptors (29). It remains to determine which of these death receptors could be implicated and how GAL1 can influence this apoptotic pathway.

In pathological situations such as multiple myeloma (MM), malignant PC, which accumulate in the BM, express high levels of GAL1 (21). The bad prognosis associated with GAL1 expression by tumor cells or by the microenvironment has been mostly related to GAL1-mediated anti-tumor T cell apoptosis (6). However, taking into account our results, it is conceivable that the high ectopic level of intracellular GAL1 protects MM cells from apoptosis. Thus, GAL1 could be considered as a new therapeutic target in MM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Poirier for providing GAL1 deficient mice, F. Mallet and A. Bole for helping us in the ELISPOT and ELISA technique, respectively and the flow cytometry facility for expert technical assistance. We wish to gratefully acknowledge Lee Leserman for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the ANR (Agence Nationale de la recherche, 05-BLAN-0035-01) and ARC (Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, contract n°1089) and institutional grants from INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale) and CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). AA was funded by ANR and ME by a FEBS long-term fellowship and by the Wellcome Trust (Programme Grant Number 083650/Z/07/Z).

Abbreviations

- ASC

antibody secreting cell

- BM

bone marrow

- GAL1

galectin 1

- PB

plasmablast

- PC

plasma cell

- WT

wild type

References

- 1.Barondes SH, Castronovo V, Cooper DN, Cummings RD, Drickamer K, Feizi T, Gitt MA, Hirabayashi J, Hughes C, Kasai K, et al. Galectins: a family of animal beta-galactoside-binding lectins. Cell. 1994;76:597–598. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne Y, Bolgiano B, Liao DI, Strecker G, Cantau P, Herzberg O, Feizi T, Cambillau C. Crosslinking of mammalian lectin (galectin-1) by complex biantennary saccharides. Nat struct biol. 1994;1:863–870. doi: 10.1038/nsb1294-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ. Identification of galectin-3 as a factor in pre-mRNA splicing. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1213–1217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vyakarnam A, Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ. Evidence for a role for galectin-1 in pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4730–4737. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes RC. Secretion of the galectin family of mammalian carbohydrate-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:172–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camby I, Le Mercier M, Lefranc F, Kiss R. Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology. 2006;16:137R–157R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danguy A, Camby I, Kiss R. Galectins and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins as modulators of tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:29–41. doi: 10.1038/nrc1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perillo NL, Pace KE, Seilhamer JJ, Baum LG. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by galectin-1. Nature. 1995;378:736–739. doi: 10.1038/378736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinovich GA, Iglesias MM, Modesti NM, Castagna LF, Wolfenstein-Todel C, Riera CM, Sotomayor CE. Activated rat macrophages produce a galectin-1-like protein that induces apoptosis of T cells: biochemical and functional characterization. J Immunol. 1998;160:4831–4840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matarrese P, Tinari A, Mormone E, Bianco GA, Toscano MA, Ascione B, Rabinovich GA, Malorni W. Galectin-1 sensitizes resting human T lymphocytes to Fas (CD95)-mediated cell death via mitochondrial hyperpolarization, budding, and fission. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6969–6985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias-Baruffi M, Zhu H, Cho M, Karmakar S, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Dimeric galectin-1 induces surface exposure of phosphatidylserine and phagocytic recognition of leukocytes without inducing apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41282–41293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stowell SR, Karmakar S, Stowell CJ, Dias-Baruffi M, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Human galectin-1, -2, and -4 induce surface exposure of phosphatidylserine in activated human neutrophils but not in activated T cells. Blood. 2007;109:219–227. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez JD, Baum LG. Ah, sweet mystery of death! Galectins and control of cell fate. Glycobiology. 2002;12:127R–136R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs-Solyom F, Blasko A, Fajka-Boja R, Katona RL, Vegh L, Novak J, Szebeni GJ, Krenacs L, Uher F, Tubak V, Kiss R, Monostori E. Mechanism of tumor cell-induced T-cell apoptosis mediated by galectin-1. Immunol Lett. 2010;127:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espeli M, Mancini SJ, Breton C, Poirier F, Schiff C. Impaired B-cell development at the pre-BII-cell stage in galectin-1-deficient mice due to inefficient pre-BII/stromal cell interactions. Blood. 2009;113:5878–5886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mourcin F, Breton C, Tellier J, Narang P, Chasson L, Jorquera A, Coles M, Schiff C, Mancini SJ. Galectin-1-expressing stromal cells constitute a specific niche for pre-BII cell development in mouse bone marrow. Blood. 2011;117:6552–6561. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-323113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CM, Chiu YK, Hsu TL, Lin IY, Hsieh SL, Lin KI. Galectin-1 promotes immunoglobulin production during plasma cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2008;181:4570–4579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirier F, Robertson EJ. Normal development of mice carrying a null mutation in the gene encoding the L14 S-type lectin. Development. 1993;119(4):1229–1236. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallies A, Hasbold J, Tarlinton DM, Dietrich W, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Nutt SL. Plasma cell ontogeny defined by quantitative changes in blimp-1 expression. J Exp Med. 2004;200:967–977. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer AL, Lin KI, Kuo TC, Yu X, Hurt EM, Rosenwald A, Giltnane JM, Yang L, Zhao H, Calame K, Staudt LM. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Threadgill DW, Dlugosz AA, Hansen LA, Tennenbaum T, Lichti U, Yee D, LaMantia C, Mourton T, Herrup K, Harris RC, et al. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science. 1995;269:230–234. doi: 10.1126/science.7618084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai CM, Guan CH, Hsieh HW, Hsu TL, Tu Z, Wu KJ, Lin CH, Lin KI. Galectin-1 and galectin-8 have redundant roles in promoting plasma cell formation. J Immunol. 2011;187:1643–1652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baum LG, Pang M, Perillo NL, Wu T, Delegeane A, Uittenbogaart CH, Fukuda M, Seilhamer JJ. Human thymic epithelial cells express an endogenous lectin, galectin-1, which binds to core 2 O-glycans on thymocytes and T lymphoblastoid cells. J Exp Med. 1995;181:877–887. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perillo NL, Uittenbogaart CH, Nguyen JT, Baum LG. Galectin-1, an endogenous lectin produced by thymic epithelial cells, induces apoptosis of human thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1851–1858. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabinovich GA, Alonso CR, Sotomayor CE, Durand S, Bocco JL, Riera CM. Molecular mechanisms implicated in galectin-1-induced apoptosis: activation of the AP-1 transcription factor and downregulation of Bcl-2. Cell death Differ. 2000;7:747–753. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vespa GN, Lewis LA, Kozak KR, Moran M, Nguyen JT, Baum LG, Miceli MC. Galectin-1 specifically modulates TCR signals to enhance TCR apoptosis but inhibit IL-2 production and proliferation. J Immunol. 1999;162:799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi B, Espeli M, Schiff C, Gauthier L. Clustering of pre-B cell integrins induces galectin-1-dependent pre-B cell receptor relocalization and activation. J Immunol. 2006;177:796–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tourneur L, Chiocchia G. FADD: a regulator of life and death. Trends Immunol. 2010;7:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.