Abstract

Chronic kidney disease is assuming epidemic proportions, and an increasing number of clinical trials are testing treatments developed to improve morbidity and mortality. Surprisingly, however, a large proportion of these trials have had negative or neutral results. When trials unexpectedly demonstrate either no benefit or a detrimental impact of a treatment, especially when that treatment is already used in practice, critics commonly argue that the results were dictated by flawed trial design rather than the intrinsic properties of the treatment. In kidney disease therapeutics, trials commonly rely on observational data and test the hypothesis that these associations may be extrapolated to cause-and-effect. Other key issues in trial design that may affect outcomes include the impact of enrolling relatively healthier subjects, the complexity of recruiting participants with specific characteristics while maintaining generalizability, and the subtleties of event adjudication and quality of life assessments. In this article, general principles of trial design will be discussed and the potential lessons learned from recent trials in nephrology will be critically reviewed.

Keywords: nephrology, clinical trial, CHOIR, CREATE, HEMO, MDRD

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are complex, chronic conditions that affect nearly 17% of the US population.1 Extensive basic and clinical research has been conducted during the past several decades to improve the often dismal outcomes in patients with these conditions. Although results from laboratory investigations, observational studies, and clinical trials in populations other than those with CKD and ESRD have often suggested promising therapeutic approaches, a growing list of randomized controlled trials in nephrology have not rejected their null hypotheses or have had rather counterintuitive and unexpected negative results. For example, the Correction of Hemoglobin and Outcomes in Renal Insufficiency (CHOIR) and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction by Early Anemia Treatment with Epoetin Beta (CREATE) trials did not show a benefit of greater anemia correction in a CKD population; the Hemodialysis Study (HEMO) and Adequacy of Peritoneal Dialysis in Mexico trials did not support the aggressive removal of small solutes from ESRD patients; and the German Diabetes and Dialysis Study (Die Deutsche Diabetes Dialyse Studie, 4D) did not demonstrate improved outcomes with atorvastatin in hemodialysis (HD) patients with diabetes mellitus.2-6

Why have there been so many trials in nephrology that have failed to reject their null hypotheses? There are at least two possibilities: first, the null hypothesis is true (that is, the treatment does not result in the anticipated benefit); and second, subtleties in trial design affected comparison of outcomes. Our goal in this review is not to criticize individual trials, but to raise points for discussion about potential methodological ‘lessons learned.’ This review is organized to follow the natural progress in the design of a clinical trial to include the formulation of the clinical question, the designation of the study population and basic trial design, subject recruitment, detection of end points, and assessment of quality of life (QOL)7 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical trial design problems, examples, and possible solutions

| Step in design | Randomized clinical trial example | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical question | CHOIR, CREATE | Limitations of observational data for study design | Use clinical trial data from other fields, if available |

| 4D | Extrapolation from general population | Use CKD/ESRD population data, if available | |

| Study population | MDRD | Healthy volunteer bias | Enroll a more representative sample |

| HEMO | Selection bias | Enroll a more representative sample | |

| Basic study design | Treat to Goal | Paired outcome analysis | Avoid nonmortality comparisons |

| NECOSAD | Insufficient enrollment | Revise inclusion/exclusion criteria | |

| Choice and detection of end points | CHF, GFR | Wide variability in end-point definition | Standardize end-point definitions |

| Assessment of QOL | ESRD | High prevalence of psychiatric illness | Avoid over-interpretation |

CHF, congestive heart failure; CHOIR, Correction of hemoglobin and outcomes in renal insufficiency; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CREATE, cardiovascular risk reduction by early anemia treatment with epoetin beta; 4D, Die Deutsche Diabetes Dialyse Studies; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HEMO, hemodialysis study; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease; NECOSAD, Netherlands cooperative study on the adequacy of dialysis.

THE CLINICAL QUESTION

Reliance on observational data

Most large clinical trials in nephrology and other disciplines are designed on the basis of the results of observational studies. For instance, with respect to anemia management, a wealth of data from numerous countries indicated that increasing hemoglobin (Hb) in both CKD and ESRD patients was associated with lower all-cause and cardiac mortality, lower rate and length of hospitalization, and lower health-care expenditures.8-12 These reports strongly suggested that the treatment of anemia with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents is associated with lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.13,14

On the basis of these studies, randomized controlled trials were performed to test the hypothesis that anemia correction to higher levels with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents improves cardiovascular outcomes. The Normal Hematocrit study randomized 1265 ESRD patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) or ischemic heart disease to epoetin alfa dosed to achieve a hematocrit of either 30 or 42%.15,16 The trial was halted early when the high-hematocrit group was noted to have a trend toward increased mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) that approached statistical significance (interim report, relative risk (RR) 1.3; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.9–1.9 and final data set, RR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9–1.8). Similarly, CHOIR randomized 1432 patients with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) 15–50 ml/min/1.73 m2) to epoetin alfa dosed to a target Hb 11.3 versus 13.5 g/100 ml (ref. 5). This trial, too, was stopped early by the Data Safety Monitoring Board.17 The final results demonstrated a greater risk of the overall end point of death, CHF hospitalization, stroke, and MI in the group randomized to the higher Hb target (hazard ratio (HR) 1.34; 95% CI 1.03–1.74).5 Finally, CREATE randomized 603 patients with CKD (estimated GFR 15–35 ml/min/1.73 m2) to epoetin beta dosed for a target Hb 10.5–11.5 versus 13–15 g/100 ml. This trial went to completion with no difference in cardiovascular events between groups (HR 0.78; 95% CI 0.53–1.14) but a higher rate of dialysis initiation (42 versus 37%, P = 0.03) and hypertension (30 versus 20%, P = 0.005) in the group randomized to the higher Hb target.2 The significantly worse event rate in CHOIR, compared with CREATE, may be explained by (1) the inclusion of twice as many diabetics (49 versus 26%) with three times the mortality rate (29 versus 9%) and (2) the enrollment of over twice as many total patients, plausibly with greater power to detect a difference in the primary end point.

Clearly, the randomized data did not confirm and, in fact, refuted the conclusions that nephrologists drew from the observational data. These results have subsequently been the subject of much speculation, with hypotheses including high-dose erythropoiesis-stimulating agent toxicity, innate resistance of some patient populations to erythropoiesis-stimulating agent, increased use of intravenous iron, and decreased Kt/V (in ESRD patients) in the high-Hb/hematocrit groups. Additionally, it has been suggested that some underlying factor(s) causing the anemia, not the anemia itself, is detrimental.2 Regardless of the underlying mechanism, these trials did not show that complete correction of anemia, which seemed practically axiomatic from the observational data, improved outcomes. What lessons can be learned from this example? Certainly not that it is inappropriate to generate hypotheses based on multiple, consistent observational studies. One lesson, as applied to individual clinical scenarios, might be that observational data need to be confirmed in the vast majority of clinical scenarios in a randomized trial design. The potential for and significance of uncontrolled and under-recognized confounding in patients with CKD and ESRD cannot be underscored enough.

Extrapolation of results from other populations

As therapeutic trials typically have limited the number of patients with CKD, clinical practice has often moved forward based on extrapolation from therapeutic success in the broader patient population and secondary post hoc analyses of subgroups of CKD patients in these trials. Only later, if at all, have trials been done to attempt to confirm this extrapolation in a prospectively designed clinical trial with adequate power within the CKD population. As an example, the 4D trial randomized 1255 subjects with diabetes mellitus and ESRD to either 20 mg/day of atorvastatin or placebo.6 Prior to that trial, several different statins had been shown to reduce cardiovascular events by 20–30% in patients with type 2 diabetes without CKD.18-20 Given the high cardiovascular event rate in patients with ESRD and the demonstrated efficacy of statins in the general population, it was hypothesized that patients with ESRD should have a similar benefit. As would be expected, rates of MI or death from coronary heart disease in 4D was reportedly the highest of any trial of statin therapy, reflecting this high incidence of cardiovascular disease in the ESRD population. However, despite lowering the low-density lipoprotein concentration from 127 to 72 mg/100 ml, atorvastatin produced only a modest decrease in the primary end point of cardiac death, nonfatal MI, and stroke (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.77–1.10).

This negative or neutral result may reflect a phenomenon encountered in nephrology and somewhat erroneously labeled as ‘reverse epidemiology.’ In ESRD and advanced CKD patients, in contrast to those with normal kidney function, higher low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and total cholesterol are often associated with lower mortality.21-23 Other risk factors, such as hyperhomocysteinemia and obesity, also have protective associations with outcomes in the ESRD population.24,25 In many of these reports, the expected association of these risk factors with poor outcomes is restored by adjusting for nutritional and inflammatory markers. These findings are thought to reflect the adverse effects of the malnutrition–inflammation–cachexia syndrome rather than any protective effects of hyperlipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, or obesity themselves. Thus, ‘reverse epidemiology’ is merely routine confounding with an association not seen with the general population. While these data and the results of 4D suggest that the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease in the ESRD and the general populations may be quite different (for example, ESRD patients experience accelerated medial arteriosclerosis, whereas non-CKD patients classically develop intimal atherosclerosis26), they may also suggest the need to carefully consider the features of the trials in subjects with normal kidney function in the design of a trial in ESRD. Hence, treatments effective for one group may not be effective for the other. Specifically, in this example, does a single level of statin dosing or a single threshold for low-density lipoprotein lowering confer the same risk or benefit in a cachectic patient with ESRD as it does in a nutritionally replete ESRD patient or a nutritionally replete patient with normal kidney function? If the associations that affect ESRD and CKD patients are different from those of the general population, these differences should be reflected in a careful reexamination of the trial design as we move from one population to another. Further, it may not be appropriate to assume that the time course of benefit in the general population will be replicated in the population with ESRD.

The 4D study illustrates another lesson inherent in the ESRD and CKD populations: the potential for a low signal-to-noise ratio. At first glance, ESRD patients with diabetes mellitus appear ideally suited to test the effect of statins on cardiovascular mortality. In the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), ESRD patients have a sevenfold higher mortality rate than the collective Medicare cohort over age 65 (357 versus 51.5 deaths per 1000 patient-years, respectively), and heart disease alone claims 120–130 lives per 1000 patient-years among ESRD patients with diabetes.27 While the rate of death due to cardiac causes in 4D was somewhat lower, being 54 deaths per 1000 patient-years (see ‘The Study Population’ below), the authors noted that sudden cardiac death, an end point that they felt, a priori, would not be affected by statin treatment, accounted for approximately 60% of the observed cardiovascular mortality.28,29 It is noteworthy that secondary analysis showed that atorvastatin treatment did reduce the rate of all cardiac events combined, including nonfatal MI and revascularization (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.68–0.99).6 Perhaps the ‘noise’ of sudden cardiac death, a frequent outcome potentially not improved by atorvastatin treatment, may have overwhelmed the ‘signal’ of ischemic coronary events that were affected by atorvastatin. Whether ongoing statin treatment can modify outcomes from certain types of ischemic acute coronary syndromes is not clear,30,31 but is supported to some extent by 4D. More broadly, the high rate of cardiac death in CKD and ESRD patients, compared with subjects with normal renal function, is likely comprised of a heterogeneous mix that deserves tremendous scrutiny at the stage of trial design, when expected differences between treatment groups is proposed. This heterogeneity could mask beneficial effects of therapy.

THE STUDY POPULATION

During trial enrollment, the potential to inadvertently recruit patients or subjects who are healthier and more motivated than individuals in the overall population to which one would like to generalize results (healthy volunteer bias) is a well-known phenomenon. Contributing to this possibility, many trials deliberately exclude subjects with comorbidities that would limit lifespan and subsequent power (for example, expected lifespan <6 months). Although this practice is appropriate to limit patient heterogeneity as described above, if subjects in the sample are not as ‘sick’ as those in the original population, event rates may be underestimated and the study may be underpowered to detect a benefit of therapy (type II error). Given the unfortunate severely shortened life expectancies of patients with kidney disease, exclusion criteria such as this may subjectively disqualify a larger proportion of the population than truly appreciated in the design phase.

A potential example of the former is the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD), which consisted of two trials to investigate whether dietary protein restriction in CKD patients could slow the rate of decline of GFR.32 In study A, 585 subjects with GFR 22–55 ml/min/1.73 m2 were randomized to receive a usual or low-protein diet (1.3 or 0.58 g protein/kg body weight/day, respectively). Study B assigned 255 subjects with GFR 13–24 ml/min/1.73 m2 to a low- or very low protein diet (0.58 or 0.28 g protein/kg body weight/day, respectively). The effect of a low- or very low protein diet was not significant in either group: the mean decline in GFR was 1.2 ml/min over 3 years less in the low-protein compared with the usual diet group (study A, 95% CI −1.1 to 3.6) and 0.8 ml/min/year less in the very low compared to the low-protein group (study B, 95% CI −0.1 to 1.8). Although MDRD was powered to detect a difference of 30% in the rate of decline in GFR with dietary protein restriction, the authors noted that the power to detect this difference was weakened by a slower loss of GFR than expected (3.8 instead of 6.0 ml/min/year).32,33 Subsequent analysis revealed that subjects recruited for the study did not demonstrate evidence of progressive renal disease, and 15% of those in the study A control arm had no evidence of GFR loss whatsoever, thus undermining the ability of the trial to observe any effect on rates of GFR decline.34 The slower loss of GFR may also have been due to (1) the exclusion of diabetics, who may have benefited from dietary protein restriction; (2) the inclusion of 200 patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, who did not show benefit; and (3) the low proportion (15%) of black patients in the sample, who had a significantly faster decline in GFR than the remaining patients (19 versus 11 ml/min/3 years, P = 0.02).32,35,36 Finally, post hoc analysis indicated that dietary protein restriction may have been beneficial in certain subgroups within the MDRD sample (that is, those with faster rates of GFR loss or high-grade baseline protein-uria).33,34 Thus, recruitment of subjects with more risk factors for GFR loss might have produced quite different results.

The generalizability of the results may be heavily influenced by the demographics of the subjects enrolled, which is in turn dependent on the diversity of site selection. In the HEMO study, 1846 subjects were recruited from 72 dialysis units at 15 clinical centers.3 Although a high number of centers should arguably enhance generalizability by allowing for the inclusion of multiple geographical and practice pattern factors, such an outcome may not have occurred in this instance. Notably, the participants in the HEMO study were 63% African-American, compared with 32–33% in the USRDS sample of ESRD patients for the same period, indicating a potential geographical influence on recruitment due to site selection.27 In addition, subjects were also relatively young (HEMO mean age 57.6 ± 14.0 versus USRDS median age 64.5 years) and were neither obese (mean dry weight 69.2 ± 14.7) nor malnourished (mean albumin 3.6 ± 0.4 g/100 ml).37,38 Although it is not likely in this example that a different selection of sites would have impacted study outcome, the principle should always be considered in the design of a trial and site selection.

On the other hand, some trials have results severely affected by insufficient enrollment. For example, the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis was designed to test the 2-year equivalence of HD and peritoneal dialysis (PD) for incident ESRD patients.39 The total required sample size was 100 subjects to be able to detect a 10-point difference in quality-adjusted life years score. However, after 3 years, only 38 subjects had been recruited. Despite unsuccessful enrollment, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, no significant differences were found in the 2-year mean quality-adjusted life years score (3.1; 95% CI −9.9 to 16.1) or 5-year mortality (HD versus PD, HR 3.6; 95% CI 0.8–15.4). In this case, the inability to enroll enough subjects dramatically affected the strength of the conclusions that HD and PD yield equivalent outcomes.

STUDY DESIGN AND COMPARISON OF OUTCOMES

Interventional studies randomize subjects to different treatment arms and compare outcomes. Randomization minimizes, to the extent possible, the effects of known and unknown confounders on the differences in outcomes by attempting to equally distribute them between or among arms. Another powerful design for randomized clinical trials is the comparison of paired outcome data within an individual. Using each subject as his or her own control in the analysis of an intermediate outcome may reduce the impact of individual variation due to severity of illness. However, the death or dropout of subjects between the baseline and follow-up measurements may result in informative censoring. An example of both designs is the Treat to Goal study, which randomized 200 prevalent dialysis patients to sevelamer or calcium-based phosphate binders to compare serum phosphorus, calcium, and parathyroid hormone levels as the primary outcomes and coronary and aortic calcification at baseline and 1 year as secondary outcomes.40 Baseline calcification scores were obtained for 186 patients, but 1-year scores were available for only 71% of initial cohort, and a total of 11 deaths occurred during the course of the study. Although the mortality rate in this study (55 deaths per 1000 patient-years) was relatively low as compared with USRDS data, the extent to which it could affect the results cannot be estimated. Longer trials with dialysis patients selected to represent the national mortality rate of 200–300 deaths per 1000 patient-years could be greatly impacted.27 In CKD and ESRD patients with such high mortality, pairing of outcomes may thus be problematic.

A perceived problem that is arguably no different from the general population of studies is the perceived success of randomization in equally distributing potential confounders between or among treatment groups. When an unexpected trial result is obtained, a failure of randomization is a frequently cited limitation. However, our ability to adequately identify and quantify the most important ‘known predictors of mortality’ is arguably and unfortunately limited. One cohort study of incident dialysis patients demonstrated that age, comorbidity score, and functional status captured only 28% of the log likelihood of 1-year mortality.41 A study of prevalent dialysis patients, faring slightly better, found that age, diabetic status, and assessment of biopsychosocial care need explained 32–40% of the variance in the mental and physical health components of the SF-36 QOL survey.42 One of the best prediction models, incorporating detailed comorbidity data, only produced an area under the receiver–operator characteristics curve of 0.77.43 These results suggest that many of the predictors of clinical outcomes in ESRD patients are unknown, and that our ability to judge whether they have been equally distributed between treatment arms may be difficult.

CHOICE AND DETECTION OF END POINTS

Some end points clearly defined in the reference population may be more difficult to determine in the CKD and ESRD populations. Among these is the diagnosis of MI. Many CKD patients have baseline elevations in cardiac troponins in the absence of acute myocardial injury that, although correlating with clinical outcomes, affect the ability to adjudicate acute MI. In addition, electrolyte abnormalities, left ventricular hypertrophy, and pericarditis can also affect electrocardiogram interpretation.44 Hospitalization for CHF is another end point which, in its definition phase, generates much discussion trying to balance the underlying pathophysiology with the practicality of the clinical information that would be available on a case basis. In CHOIR, CHF was defined as an unplanned admission during which the subject received intravenous inotropes, diuretics, or vasodilators.5 In contrast, a study by Smith et al.45 in the Journal of Cardiac Failure defined hospitalization for CHF as either a diagnosis of CHF or a chest X-ray consistent with CHF on admission and documentation of 15 possible signs and symptoms of CHF within 3 days. Although variations between studies in the definitions of end points do not invalidate individual results, they certainly make assumptions and comparison of trials difficult, potentially and erroneously predisposing some to be concerned about the validity of results.

Changes in kidney function, as a study outcome, can also be difficult to accurately assess. Serum creatinine-based measurements of GFR may overestimate renal function if, for example, a patient loses muscle mass after a stroke. Although stroke is less common in CKD and ESRD patients, even clinically unremarkable events, such as changes in volume status or even taking creatine supplements or eating cooked meat, can affect the serum creatine and may be more common and under-recognized.46,47 Notwithstanding the ability to accurately track kidney function, the use of ESRD incidence as an outcome may also have limitations. Although the National Kidney Foundation–Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines recommend starting renal replacement therapy in the GFR range of 10–15 ml/min/1.73 m2, the point at which CKD becomes ESRD (that is, when dialysis must be initiated) is sometimes subjective. Individual patient factors, such as age, overall health, symptoms that may be judged uremic, fluid balance, and dietary and medication compliance must also be factored into the decision.48 Underscoring the subjective and changing practice patterns over time, the average GFR at dialysis initiation in the USRDS database has increased from 7.5 to 10.1 ml/min/1.73 m2 over the past decade, demonstrating a systematic change in objective factors that could mask this outcome over time.27

Finally, hospitalization for dialysis access management in ESRD patients is associated with major mortality and morbidity. Investigators frequently struggle with whether to include this event as an end point. Vascular access catheter-related infection and sepsis occur at respective rates of 1.3 and 1.6 episodes per patient-year; rates are lower but still significant for those with either arteriovenous grafts or fistulae.27 HD patients are frequently admitted to undergo catheter removal or arteriovenous access declotting or angioplasty, and PD patients are often hospitalized for episodes of peritonitis. ESRD patients are thus subject to unique complications, and including assessments of access-related hospitalizations during clinical trials would be prudent to fully evaluate the benefits or harms of an intervention. Careful consideration of how to handle the complicated scenario of patients experiencing morbidity or mortality following an access procedure and how these events should be adjudicated need to be discussed and vetted at both the individual trial level and potentially, and perhaps more importantly, among the research community as a whole.

Clearly, the most important clinical end points in evaluating the benefits of therapy are mortality and major morbidity. However, when the potential benefits of therapy are initially being investigated, the use of intermediate outcomes, with the caveat that they truly satisfy the McMaster criteria as proper surrogates, may also be of value. For example, the use of proteinuria and progression of CKD are appropriate in selected nephrology trials, given their correlation with renal survival. It is noteworthy that some studies that have focused on such intermediate outcomes, such as those demonstrating the effectiveness of angiotensin receptor blockers in diabetic kidney disease, have had positive results.49,50

ASSESSMENT OF QOL

As clinicians, our goals are to attempt to improve both the quantity and QOL. Arguably, the comorbidities and treatments of patients with CKD and ESRD affect their QOL dramatically. Methodologically, however, studying QOL is likely complicated by the high frequency of both functional and organic psychiatric disorders in CKD and ESRD patients that may affect the ability to identify and quantify a change in QOL due to some form of treatment. A total of 3–8% of ESRD patients carry the diagnosis of dementia, although recent analysis suggests that cognitive impairment is present in a staggering 87% of the ESRD population.51-53 How to quantify the degree of cognitive impairment and how it affects assessment of QOL is not entirely clear. Furthermore, depression is also common, occurring at a rate of 84% in one group of 380 PD patients.54 Although this last study suggested that pharmacological therapy was associated with improvement in the Beck Depression Inventory score, 38% of patients who failed to improve had coexisting personality disorders. It is not known how this high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity among the ESRD population affects assessments of mental health or cognitive capacity in clinical trials where diagnoses such as depression are not the focus, but without attention, these conditions clearly would bias findings toward the null.

Moreover, the instruments typically used to measure QOL may have significant limitations when applied to ESRD patients.55 For example, commonly used depression inventories may not be valid in the dialysis population. QOL questionnaires are also frequently, and inappropriately, used in countries other than those in which they were validated. Lastly, QOL measured in different groups of patients, such as those undergoing different types of renal replacement, are often compared without standardization for age, gender, and comorbidity, which would require the use of generic as well as modality-specific instruments.

CONCLUSION

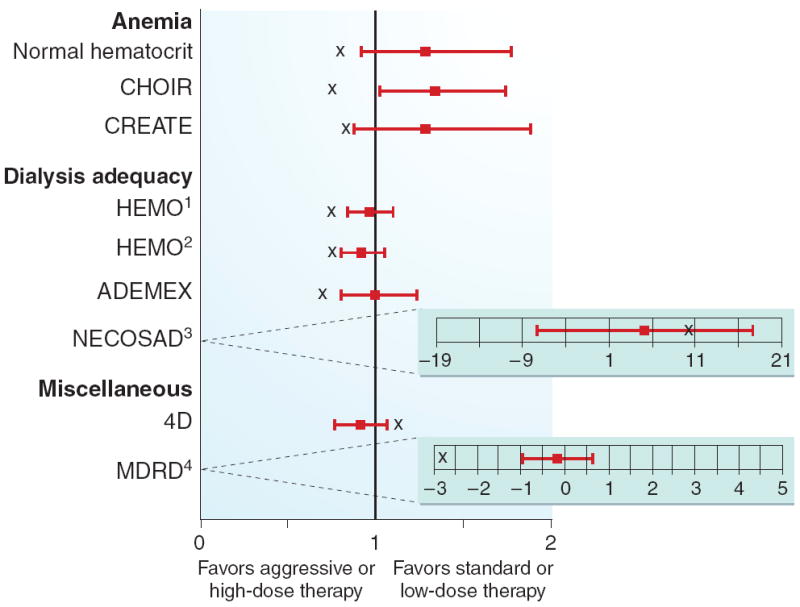

There are numerous methodological possibilities to address the question of why so many trials in nephrology have had negative or neutral results (see Figure 1). Many obstacles are present in the optimal design of successful clinical trials in nephrology (see Table 1). These problems include reliance on observational data and extrapolation from the non-CKD population in designing relevant study questions, healthy volunteer effect during study recruitment, informative censoring and unequal randomization in the study design, lack of generalizability and insufficient numbers of participants, variability in definitions of clinical end points, and inaccurate QOL assessment.

Figure 1. Results from representative negative or neutral trials in nephrology.

Box plot indicates point estimate (HR or RR) with 95% CI. ‘X’ signifies the estimate the study was powered to detect. Point estimates reported are for mortality or composite end points including mortality (except the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis and MDRD, see footnotes). See text for abbreviations. (1) high versus low dose; (2) high versus low flux; (3) QOL, HD vs PD; (4) change in GFR (ml/min/year), very low versus low protein diet.

In some cases, well-established analytical techniques may be helpful in overcoming some of these limitations. For instance, imputation of missing values can be helpful in dealing with informative censoring. Unequal randomization is frequently addressed by adjusting outcome variables for the parameters in question. Groups of trials that are underpowered by insufficient participation may be considered collectively using meta-analysis.

Although these problems are not unique to nephrology trials, we suggest a focus by nephrologists involved in clinical research to examine lessons learned to improve the yield of future trials in nephrology. The development, vetting, and general acceptance of common principles to guide trial design in nephrology studies would likely enhance our ability to accomplish trials as well as compare results between trials. If we consider and adopt methodological lessons learned, we can minimize, but never eliminate, major concerns about the impact of different design features on results and focus on learning from positive, negative, and neutral trials.

Acknowledgments

J.K.I. was supported by NIH grant KL2 RR024127 and has received investigator-initiated grant support from Genzyme. U.D.P. is the recipient of grant K23 DK075929 from the National Institutes of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases and has received grant support from Abbott Laboratories. L.A.S. has received consulting fees from Ortho Biotech Clinical Affairs, Nabi Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Fresenius Medical Care, Kuraha, Affymax, and Acologix; lecture fees from Nabi Biopharmaceuticals, Fresenius Medical Care, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Genzyme, Abbott, Amgen, and Ortho Biotech; and grant support from Ortho Biotech Clinical Affairs, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Genzyme.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

All the authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Saydah S, Eberhardt M, Rios-Barrow N, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors—United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Cheung AK, et al. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2010–2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paniagua R, Amato D, Vonesh E, et al. Effects of increased peritoneal clearances on mortality rates in peritoneal dialysis: ADEMEX, a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1307–1320. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1351307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanner C, Krane V, Marz W, et al. Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:238–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman LM, Furberg C, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. 3. Springer-Verlag Inc.; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins AJ, Li S, St Peter W, et al. Death, hospitalization, and economic associations among incident hemodialysis patients with hematocrit values of 36–39% J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2465–2473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12112465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma JZ, Ebben J, Xia H, et al. Hematocrit level and associated mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:610–619. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V103610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ofsthun N, Labrecque J, Lacson E, et al. The effects of higher hemoglobin levels on mortality and hospitalization in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1908–1914. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Vlagopoulos PT, et al. Effects of anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy on cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1803–1810. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, et al. The impact of anemia on cardiomyopathy, morbidity, and and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mocks J. Cardiovascular mortality in haemodialysis patients treated with epoetin beta—a retrospective study. Nephron. 2000;86:455–462. doi: 10.1159/000045834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue JL, St Peter WL, Ebben JP, et al. Anemia treatment in the pre-ESRD period and associated mortality in elderly patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:1153–1161. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.36861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Besarab A, Goodkin DA, Nissenson AR. The normal hematocrit study—follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:433–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc076523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. Anaemia of CKD—the CHOIR study revisited. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1806–1810. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Pharmacologic lipid-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: background paper for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:650–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang CK, Ho TI, Hsu SP, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: association with mortality and hospitalization in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2005;23:134–140. doi: 10.1159/000083529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Inverse association between lipid levels and mortality in men with chronic kidney disease who are not yet on dialysis: effects of case mix and the malnutrition-inflammation-cachexia syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;18:304–311. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiner DE, Sarnak MJ. Managing dyslipidemia in chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1045–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD. Obesity paradox in patients on maintenance dialysis. Contrib Nephrol. 2006;151:57–69. doi: 10.1159/000095319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suliman M, Stenvinkel P, Qureshi AR, et al. The reverse epidemiology of plasma total homocysteine as a mortality risk factor is related to the impact of wasting and inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;22:209–217. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.London GM, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, et al. Arteriosclerosis, vascular calcifications and cardiovascular disease in uremia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14:525–531. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000168336.67499.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2006 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newby LK, Kristinsson A, Bhapkar MV, et al. Early statin initiation and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;287:3087–3095. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briel M, Schwartz GG, Thompson PL, et al. Effects of early treatment with statins on short-term clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:2046–2056. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hulten E, Jackson JL, Douglas K, et al. The effect of early, intensive statin therapy on acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1814–1821. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, et al. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levey AS, Greene T, Beck GJ, et al. Dietary protein restriction and the progression of chronic renal disease: what have all of the results of the MDRD study shown? Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2426–2439. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitch WE. Dietary therapy in uremia: the impact on nutrition and progressive renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;75:S38–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klahr S, Breyer JA, Beck GJ, et al. Dietary protein restriction, blood pressure control, and the progression of polycystic kidney disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2037–2047. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedrini MT, Levey AS, Lau J, et al. The effect of dietary protein restriction on the progression of diabetic and nondiabetic renal diseases: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:627–632. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-7-199604010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saran R, Canaud BJ, Depner TA, et al. Dose of dialysis: key lessons from major observational studies and clinical trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:47–53. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Renal Data System. USRDS 2003 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korevaar JC, Feith GW, Dekker FW, et al. Effect of starting with hemodialysis compared with peritoneal dialysis in patients new on dialysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2003;64:2222–2228. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, et al. Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ. 1999;318:217–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Jonge P, Ruinemans GM, Huyse FJ, et al. A simple risk score predicts poor quality of life and non-survival at 1 year follow-up in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:2622–2628. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miskulin DC, Martin AA, Brown R, et al. Predicting 1 year mortality in an outpatient haemodialysis population: a comparison of comorbidity instruments. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:413–420. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanderian AS, Francis GS. Cardiac troponins and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1112–1114. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith GL, Vaccarino V, Kosiborod M, et al. Worsening renal function: what is a clinically meaningful change in creatinine during hospitalization with heart failure? J Card Fail. 2003;9:13–25. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Preiss DJ, Godber IM, Gunn IR. How to measure renal function in clinical practice: eating cooked meat alters serum creatinine concentration and eGFR significantly. BMJ. 2006;333:1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39030.730949.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pline KA, Smith CL. The effect of creatine intake on renal function. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1093–1096. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. National kidney foundation-dialysis outcomes quality initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:S150–S191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurella M, Mapes DL, Port FK, et al. Correlates and outcomes of dementia among dialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2543–2548. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sithinamsuwan P, Niyasom S, Nidhinandana S, et al. Dementia and depression in end stage renal disease: comparison between hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88(Suppl 3):S141–S147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67:216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Finkelstein FO. The identification and treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. Semin Dial. 2005;18:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rebollo P, Ortega F. New trends on health related quality of life assessment in end-stage renal disease patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;33:195–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1014419122558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]