Abstract

Progressive apraxia of speech (AOS) can result from neurodegenerative disease and can occur in isolation or in the presence of agrammatic aphasia. We aimed to determine the neuroanatomical and metabolic correlates of progressive AOS and aphasia. Thirty-six prospectively recruited subjects with progressive AOS or agrammatic aphasia, or both, underwent the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) and Token Test to assess aphasia, an AOS rating scale (ASRS), 3T MRI and 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET. Correlations between clinical measures and imaging were assessed. The only region that correlated to ASRS was left superior premotor volume. In contrast, WAB and Token Test correlated with hypometabolism and volume of a network of left hemisphere regions, including pars triangularis, pars opercularis, pars orbitalis, middle frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, precentral gyrus and inferior parietal lobe. Progressive agrammatic aphasia and AOS have non-overlapping regional correlations, suggesting that these are dissociable clinical features that have different neuroanatomical underpinnings.

Keywords: apraxia of speech, aphasia, atrophy, Broca’s area, premotor cortex, hypometabolism

1. INTRODUCTION

Apraxia of speech (AOS) is a motor speech disorder in which subjects have impaired planning or programming of movements for accurate production of syllables across words, or within multisyllabic words (J. Duffy, 2006; J. R. Duffy, 2005; McNeil, Doyle, & Wambaugh, 2000). It is characterized by slow rate, articulatory distortions, distorted sound substitutions, segmentation of syllables in multisyllabic words or across words, and articulatory groping and trial and error articulatory movements. In the progressive form, AOS can be the sole presenting symptom of a neurodegenerative disease (primary progressive apraxia of speech, PPAOS (Josephs et al., 2012)), but AOS can also co-occur with agrammatic aphasia (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Hart, Beach, & Taylor, 1997; Josephs et al., 2005; Josephs et al., 2006; Knibb, Woollams, Hodges, & Patterson, 2009). Subjects who present with both AOS and agrammatic aphasia display grammatical errors in speech and writing and impairments in comprehending syntactically complex sentences (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011).

Neuroimaging studies in subjects with mixed AOS and agrammatic aphasia have found atrophy on MRI and hypometabolism on 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET in the left medial and lateral posterior frontal cortex, involving inferior, middle and superior frontal gyri, and the left insula and temporal lobe (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Josephs et al., 2010; Josephs et al., 2006; Nestor et al., 2003; Rabinovici et al., 2008). In contrast, more focal abnormalities in the superior aspects of the premotor cortex have been observed in PPAOS without any aphasia (Josephs et al., 2012). These studies therefore suggest that AOS is associated with abnormalities in superior premotor cortex, while agrammatic aphasia is more likely to be associated with abnormalities in the inferior frontal cortex, namely Broca’s area. This study aimed to test this hypothesis by examining direct correlations between measures of AOS severity and measures of aphasia severity and regional atrophy and hypometabolism in a large cohort of subjects with varying degrees of these clinical features.

2. METHODS

2.1 Subjects

A total of 36 subjects with AOS, agrammatic aphasia, or both AOS and agrammatic aphasia were included in this study. All subjects were recruited from the Department of Neurology into a prospective speech and language based disorder study between July 1st 2010 and July 31th 2012. All subjects underwent detailed speech and language examination by one of two speech-language pathologists (JRD or EAS), neurological evaluation, volumetric MRI and FDG-PET. All subjects had video and audio recordings of their formal speech and language assessment, as well as general conversation. The presence of AOS and agrammatic aphasia were determined by consensus between both speech-language pathologists based on review of the video and audio recordings, and performance on speech and language testing. Of the 36 subjects in the study, 18 subjects had both AOS and agrammatic aphasia, 17 subjects had only AOS and hence met criteria for PPAOS, and one subject had agrammatic aphasia without AOS. Of the 19 subjects with agrammatic aphasia, nine met recent clinical criteria for the agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). The remaining ten subjects did not meet criteria for the agrammatic variant of PPA because the severity of AOS was worse than the severity of agrammatic aphasia. The criteria for PPA state that deficits in language, and not deficits in the motoric formation of words, must be the most prominent clinical feature early in the disease (Mesulam, 1982, 2003). Imaging findings in 12 of the 17 PPAOS subjects have previously been published (Josephs et al., 2012). Subjects with aphasia not characterized by agrammatic spoken or written language output, for example those meeting criteria for semantic variant of PPA or logopenic variant of PPA, (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011) were not included in this study. Subjects with concurrent illnesses that could account for the language deficits, subjects meeting criteria for another neurodegenerative disorder, or subjects where MRI was contraindicated, were excluded.

2.2 Speech and Language testing

Language assessments performed in this cohort have been previously described in detail (Josephs et al., 2012) and included The Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), revised (Kertesz, 2007), Part 1, plus several writing subtests from Part 2, and a 22-item version of Part V of DeRenzi and Vignolo’s Token Test (De Renzi & Vignolo, 1962); other measures of language ability were also obtained, but are not reported here. Imaging associations with the WAB Aphasia Quotient (AQ) and Token Test were assessed. These tests were chosen since the WAB AQ provides a global measure of aphasia severity and the Token Test provides a measure of relatively complex sentence comprehension that includes a requirement for processing of grammatic and syntactic relationships (e.g. after picking up the green square, touch the white circle; touch-with the blue circle-the red square); both are appropriate for assessing agrammatic aphasia. The clinical judgment concerning the presence of agrammatism was based primarily on the presence of deficiencies in sentence length and grammar/syntax/morphology in the WAB Spontaneous Speech (conversational questions and picture description) and/or Writing Output subtests of the WAB. The Token Test was not used solely to designate subjects as agrammatic but was important as a determiner of the presence of aphasia and as a measure of complex sentence comprehension.

The severity of AOS was measured using an AOS rating scale (ASRS) which assesses the prevalence/prominence of 16 features characteristic of AOS (Josephs et al., 2012). Items included in the ASRS provided a description of AOS characteristics and quantitative index of severity. Ratings for each feature were based on the following scale: 0 = not present; 1 = detectable but not frequent; 2 = frequent but not pervasive; 3 = nearly always evident but not marked in severity; 4 = nearly always evident and marked in severity, resulting in a total possible score of 64.

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic IRB and all subjects were consented for enrollment.

2.3 MRI and PET image acquisition

All subjects underwent a standardized MRI imaging protocol at 3.0 Tesla, that included a 3D magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR/TE/T1, 2300/3/900 ms; flip angle 8°, 26-cm FOV; 256 × 256 in-plane matrix with a phase FOV of 0.94, slice thickness of 1.2 mm, in-plane resolution). All MRI scans underwent pre-processing correction for gradient non linearity (Jovicich et al., 2006) and intensity non-uniformity (Sled, Zijdenbos, & Evans, 1998). FDG-PET scans were acquired within one day of the MRI and were acquired using a PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) operating in 3D mode. Subjects were injected with 366–399 MBq of 18F-FDG in a dimly lit room with minimal auditory stimulation. Subjects were imaged after 30–38 minutes, for an 8-minute image acquisition consisting of four 2-minute dynamic frames. A low-dose CT of the brain was used for attenuation correction. Emission data were reconstructed into a 128×128 matrix with 256-mm FOV, pixel size of 2mm and 4.25mm section thickness.

2.4 MRI and PET image analysis

An atlas-based parcellation technique was employed using SPM5 and the automated anatomic labeling (AAL) atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) in order to generate grey matter volumes and mean FDG uptake values for a number of specific regions-of-interest, selected in order to assess different aspects of the language network (Turken & Dronkers, 2011). We assessed the left and right pars opercularis and pars triangularis that are considered to constitute Broca’s area, the pars orbitalis, the middle frontal gyrus, supplemental motor area, precentral gyrus, insula, superior temporal gyrus and the inferior parietal lobe. In addition, since the premotor cortex has been implicated in PPAOS (Josephs et al., 2012), we manually placed a focal ROI in the superior lateral premotor cortex. It was necessary to manually place this ROI because the AAL atlas does not include a specific premotor cortex ROI; the premotor cortex is instead part of a much larger superior frontal ROI that includes prefrontal cortex. Left and right hemisphere values were assessed separately.

In order to generate regional volumes from the MRI, all subject MRIs and the AAL atlas were spatially normalized to a customized template using the unified segmentation tool in SPM5 (Ashburner & Friston, 2005). The customized template was created using 200 healthy controls and 200 subjects with dementia (Mesulam, 1982). Then for each subject, the inverse transformation was applied to the atlas in custom template space in order to warp the atlas to the subject’s native anatomical space, and each native-space MRI was segmented into grey matter, white matter, and CSF. The grey matter probability maps for each subject were thresholded to create a binary mask, and were multiplied by the native-space AAL atlas, to generate a custom grey matter atlas for each subject, parcellated into different ROIs. Total intracranial volume (TIV) was measured and used to normalize regional grey matter volumes for differences in head size. In order to generate regional uptake values from the FDG-PET, the FDG-PET images were co-registered to the MPRAGE for each subject using 6 degrees-of-freedom rigid registration with a mutual information cost function. The native-space custom grey matter atlas for each subject was then used to extract statistics on image voxel uptake values in each ROI. Median uptake values for each ROI were divided by the median uptake value in the pontine ROI from the AAL atlas.

A spherical ROI (radius 10mm) was placed in the superior lateral premotor cortex on the customized template using the Marsbar software tool. The central coordinates were obtained from a previous study that assessed grey matter atrophy in PPAOS compared to controls (Left coordinates: x=−24, y=−5, z=52. Right coordinates: x=−32, y=−6, z=52) (Josephs et al., 2012). The ROI was applied to the MPRAGE and FDG-PET scans in custom space. The FDG-PET scans were normalized to the custom template utilizing parameters from the MPRAGE normalization. All voxels in the FDG-PET image were divided by the median FDG uptake of the pontine region to form regional FDG uptake ratio images before analysis. Grey matter volume and median FDG-PET uptake were outputted.

Voxel-level correlations using custom-space MRI and FDG-PET uptake ratio scans were also performed in order to visualize and display the results. The custom-space MRI scans were modulated and both the MRI and FDG-PET uptake ratio scans were smoothed at 8mm full width at half maximum before analysis.

2.5 Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc. Cary, NC). Distributions of the three clinical measures indicated that we could treat the WAB AQ as a continuous variable, and the Token Test and ASRS as ordinal scale variables. All MRI and FDG ROIs were continuous variables. As a result, Pearson’s correlations were used to measure the associations between WAB AQ and the imaging ROIs; while Spearman’s rank correlations were used for measuring the associations between Token Test, ASRS and the imaging ROIs. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Correlations between the ASRS and the imaging ROIs were performed for the entire cohort (n=36) since AOS (i.e. the clinical measure of interest in this analysis) was present in all cases, except one. In order to account for any potential confounds of the presence of aphasia, partial Spearman correlations were performed adjusting for the presence of aphasia. In addition, Spearman correlations between the ASRS and imaging ROIs were also performed using only the PPAOS subjects who did not have any aphasia (n=17). This represents a clean analysis of the correlates of AOS without any potential confounds of aphasia. Correlations between the WAB AQ and Token Test and the imaging ROIs were performed only in those 19 subjects who had agrammatic aphasia. The WAB AQ and Token Test correlations were not performed across the entire cohort since the findings would be driven by differences between those subjects with and without aphasia, and would not reflect regions that were specifically related to aphasia severity. Scatter-plots were created for the ROIs which showed the strongest correlations for each clinical test. Linear regression lines were added to the scatter plots to show trends.

Voxel-level correlations were performed using multiple regression analysis in SPM5. In order to match the region-level analysis, voxel-level correlations of the ASRS were assessed in the entire cohort (n=36), and within just the PPAOS subjects (n=17). Voxel-level correlations of the WAB AQ and Token Test were performed only in those subjects who had agrammatic aphasia (n=19). All analyses were masked by the patterns of atrophy/hypometabolism observed in the entire cohort when compared to controls.

We did not apply adjustment for multiple comparisons since adjustment would increase the type II errors for associations that are not null. Not adjusting for multiple comparisons has been advocated since it will result in fewer errors in interpretation when the data are not random numbers but actual observations on nature (J. R. Duffy, 2013; McNeil, Robin, & Schmidt, 2009).

3. RESULTS

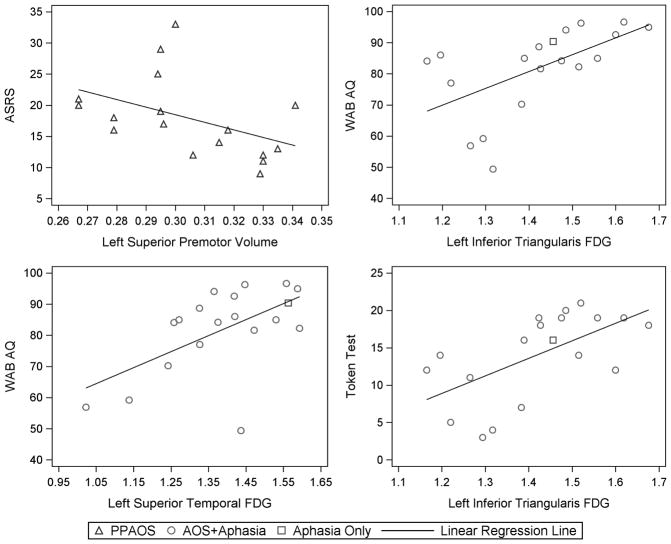

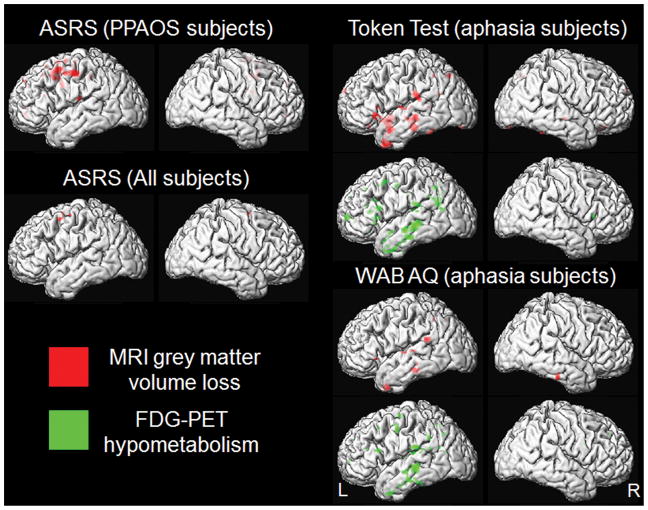

Subject demographics and test scores for the 36 study subjects are shown in Table 1. Performance on the ASRS did not significantly correlate to volume or hypometabolism in any of the ROIs across the entire cohort of 36 subjects. Only trends were identified for correlations with volume in the left premotor cortex and right supplementary motor area (Table 2). However, when associations were assessed within the subjects who had PPAOS (and therefore did not have aphasia), we observed a significant association between ASRS and volume of the left lateral premotor cortex (r=−0.55, p=0.02, Figure 1). The association between ASRS and right supplemental motor area remained only a trend. The voxel-level analysis showed correlations between ASRS and superior premotor cortex volume (medial and lateral), but not FDG-PET hypometabolism, in both the entire cohort and the PPAOS subjects (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Summary demographics

| Clinical feature | Entire cohort (n=36) | Subjects with PPAOS (n=17) | Subjects with agrammatic Aphasia (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 18 (50%) | 12 (71%) | 6 (32%) |

| Age at MRI, years | 70.8 ± 7.8 [53–84] | 71.5 ± 9.0 [53–84] | 70.2 ± 6.7 [57–83] |

| Age at onset, years | 67.7 ± 8.1 [49–82] | 68.2 ± 9.7 [49–82] | 67.2 ± 6.6 [55–78] |

| Time from onset-scan, years | 3.5 ± 1.7 [1–10] | 3.7 ± 2.1 [1.5–10] | 3.2 ± 1.3 [1–5.5] |

| Education, years | 14.8 ± 2.7 [10–21] | 15.1 ± 2.4 [12–20] | 14.6 ± 2.9 [10–21] |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (/30) | 27.9 ± 3.0 [15–30] | 29.2 ± 1.0 [27–30] | 26.7 ± 3.7 [15–30]** |

| AOS present, n (%) | 35 (97%) | 17 (100%) | 18 (95%) |

| Aphasia present, n (%) | 19 (53%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (100%) |

| AOS rating scale (/64)* | 20.6 ± 10.2 [2–44] | 17.9 ± 6.5 [9–33] | 22.9 ± 12.3 [2–44] |

| Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia quotient (/100) | 89.0 ± 12.6 [49.4–100] | 97.0 ± 2.1 [94.1–100] | 81.8 ± 13.7 [49.4–96.6]** |

| Token Test (/22) | 17.0 ± 5.3 [3–22] | 20.3 ± 1.6 [16–22] | 14.1 ± 5.7 [3–21]** |

Higher scores reflect greater abnormality. Scores above 6 are two standard deviations above the mean for a group of 14 subjects with primary progressive aphasia (not examined in this study) judged clinically not to have AOS.

Significant difference between PPAOS and subjects with agrammatic aphasia at p<0.05

Data shown as mean ± standard deviation [range], or n (%)

TABLE 2.

Correlations between MRI and FDG-PET ROIs and AOS rating scale (ASRS)

| ROI | Hem | Metric | All subjects (n=36)* | PPAOS subjects (n=17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | FDG-PET | MRI | FDG-PET | |||

| Inferior Orbitalis | L | Correlation | −0.185 | 0.016 | −0.450 | 0.086 |

| P value | 0.287 | 0.926 | 0.070 | 0.743 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.126 | 0.012 | −0.362 | 0.123 | |

| P value | 0.471 | 0.945 | 0.154 | 0.639 | ||

| Inferior triangularis | L | Correlation | −0.118 | 0.000 | −0.472 | 0.029 |

| P value | 0.499 | 0.998 | 0.056 | 0.911 | ||

| R | Correlation | 0.015 | −0.043 | −0.117 | 0.027 | |

| P value | 0.933 | 0.805 | 0.655 | 0.918 | ||

| Inferior opercularis | L | Correlation | 0.051 | 0.005 | −0.078 | 0.160 |

| P value | 0.771 | 0.976 | 0.767 | 0.541 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.024 | −0.029 | −0.192 | 0.185 | |

| P value | 0.890 | 0.870 | 0.461 | 0.476 | ||

| Middle Frontal | L | Correlation | −0.092 | 0.025 | −0.333 | 0.087 |

| P value | 0.599 | 0.886 | 0.191 | 0.739 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.032 | −0.037 | −0.213 | 0.146 | |

| P value | 0.857 | 0.835 | 0.412 | 0.576 | ||

| Superior Premotor | L | Correlation | −0.314 | 0.012 | −0.552 | 0.268 |

| P value | 0.066 | 0.946 | 0.022 | 0.298 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.024 | 0.107 | −0.257 | −0.082 | |

| P value | 0.891 | 0.542 | 0.319 | 0.754 | ||

| SMA | L | Correlation | 0.027 | −0.097 | −0.147 | 0.122 |

| P value | 0.877 | 0.578 | 0.573 | 0.642 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.327 | 0.069 | −0.432 | 0.242 | |

| P value | 0.056 | 0.693 | 0.084 | 0.350 | ||

| Insula | L | Correlation | −0.126 | 0.123 | −0.385 | 0.112 |

| P value | 0.470 | 0.482 | 0.127 | 0.669 | ||

| R | Correlation | 0.026 | 0.027 | −0.105 | 0.086 | |

| P value | 0.881 | 0.878 | 0.688 | 0.743 | ||

| Superior temporal | L | Correlation | −0.015 | 0.144 | −0.255 | 0.049 |

| P value | 0.933 | 0.410 | 0.323 | 0.853 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.144 | −0.019 | −0.293 | 0.065 | |

| P value | 0.409 | 0.912 | 0.254 | 0.804 | ||

| Inferior parietal | L | Correlation | −0.140 | 0.075 | −0.375 | 0.138 |

| P value | 0.422 | 0.668 | 0.138 | 0.599 | ||

| R | Correlation | 0.039 | 0.062 | −0.097 | 0.226 | |

| P value | 0.822 | 0.721 | 0.711 | 0.383 | ||

| Precentral | L | Correlation | −0.303 | 0.024 | −0.477 | 0.025 |

| P value | 0.077 | 0.889 | 0.053 | 0.924 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.142 | 0.054 | −0.333 | 0.207 | |

| P value | 0.417 | 0.759 | 0.191 | 0.425 | ||

Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficients and p values are shown.

Partial Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficients are shown for the whole group adjusting for the presence of aphasia. P values coded as follows: p<0.01 = yellow, p<0.05 = orange

Figure 1.

Scatter-plots showing the associations between clinical measures and regional FDG-PET hypometabolism or MRI volume. Linear regression was utilized to generate the trend line. ASRS = AOS rating scale; WAB AQ = Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient

Figure 2.

Voxel-level correlations between the clinical measures and FDG-PET hypometabolism or MRI volume. Results are shown on lateral surface renders of the brain at p<0.005 uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

The Token Test showed significant correlations with FDG hypometabolism in the inferior orbitalis, inferior triangularis, inferior opercularis, middle frontal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe (Table 3). Correlations were generally stronger in the left hemisphere, with the strongest correlation with the Token Test observed with the left inferior triangularis (r=0.64, p=0.003, Figure 1). The WAB AQ showed significant correlations with FDG hypometabolism in the left inferior triangularis, middle frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobe and precentral gyrus; once again with the strongest correlations observed in the left inferior triangularis (r=0.584, p=0.009, Figure 1, Table 3). The only MRI regions which showed significant correlations with either the WAB AQ or Token Test, was the left inferior orbitalis (r=0.49, p=0.04) and left superior temporal lobe which correlated with Token Test (r=0.48, p=0.04). The voxel-level analysis showed correlations between both the Token Test and WAB AQ and atrophy and hypometabolism in the inferior frontal, temporal, and inferior parietal lobes (Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Correlations between MRI and FDG-PET ROIs and WAB-AQ and Token Test within subjects with agrammatic aphasia (n=19)

| WAB AQ | Token Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROI | Hem | Metric | MRI | FDG-PET | MRI | FDG-PET |

| Inferior Orbitalis | L | Correlation | 0.339 | 0.434 | 0.486 | 0.528 |

| P value | 0.156 | 0.063 | 0.035 | 0.020 | ||

| R | Correlation | 0.344 | 0.402 | 0.306 | 0.354 | |

| P value | 0.149 | 0.088 | 0.203 | 0.137 | ||

| Inferior triangularis | L | Correlation | 0.036 | 0.584 | 0.147 | 0.636 |

| P value | 0.885 | 0.009 | 0.547 | 0.003 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.206 | 0.418 | −0.077 | 0.568 | |

| P value | 0.398 | 0.075 | 0.755 | 0.011 | ||

| Inferior opercularis | L | Correlation | −0.208 | 0.404 | 0.033 | 0.500 |

| P value | 0.394 | 0.086 | 0.893 | 0.029 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.283 | 0.257 | −0.113 | 0.428 | |

| P value | 0.241 | 0.288 | 0.645 | 0.067 | ||

| Middle Frontal | L | Correlation | −0.154 | 0.463 | 0.160 | 0.518 |

| P value | 0.529 | 0.046 | 0.514 | 0.023 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.312 | 0.337 | −0.047 | 0.510 | |

| P value | 0.193 | 0.158 | 0.849 | 0.026 | ||

| Superior Premotor | L | Correlation | −0.063 | 0.379 | −0.059 | 0.180 |

| P value | 0.797 | 0.110 | 0.810 | 0.461 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.346 | 0.011 | −0.127 | 0.183 | |

| P value | 0.147 | 0.964 | 0.605 | 0.454 | ||

| Supplemental motor area | L | Correlation | −0.120 | 0.326 | −0.135 | 0.335 |

| P value | 0.624 | 0.174 | 0.582 | 0.160 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.096 | 0.071 | −0.029 | 0.134 | |

| P value | 0.697 | 0.773 | 0.907 | 0.584 | ||

| Insula | L | Correlation | 0.035 | 0.283 | 0.230 | 0.169 |

| P value | 0.887 | 0.240 | 0.345 | 0.488 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.253 | 0.162 | −0.071 | 0.054 | |

| P value | 0.295 | 0.507 | 0.771 | 0.827 | ||

| Superior temporal | L | Correlation | 0.396 | 0.581 | 0.482 | 0.432 |

| P value | 0.093 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.064 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.043 | 0.313 | −0.024 | 0.155 | |

| P value | 0.860 | 0.192 | 0.923 | 0.525 | ||

| Inferior parietal | L | Correlation | 0.075 | 0.565 | 0.200 | 0.564 |

| P value | 0.759 | 0.012 | 0.413 | 0.012 | ||

| R | Correlation | 0.063 | 0.356 | 0.222 | 0.237 | |

| P value | 0.797 | 0.135 | 0.362 | 0.328 | ||

| Precentral | L | Correlation | −0.195 | 0.532 | −0.189 | 0.399 |

| P value | 0.424 | 0.019 | 0.438 | 0.091 | ||

| R | Correlation | −0.352 | 0.049 | −0.205 | 0.119 | |

| P value | 0.139 | 0.843 | 0.399 | 0.628 | ||

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients and p values are shown for WAB AQ and Spearman rank Correlation Coefficients and p values are shown for the Token Test. P values coded as follows: p<0.01 = yellow, p<0.05 = orange

4. DISCUSSION

This study used a well characterized cohort of prospectively recruited subjects to demonstrate that AOS and agrammatic aphasia are associated with distinct regional abnormalities in the brain.

An AOS rating scale (ASRS), which provided a measure of AOS severity, correlated most strongly to volume of the left lateral superior premotor cortex; hence strongly implicating this region in the development of neurodegenerative AOS. This correlation was identified within the cohort of PPAOS subjects who did not have any aphasia, but was also a trend across all 36 subjects in the study. We have previously shown that subjects with PPAOS show grey matter volume loss in the supplementary motor area and the lateral premotor cortex (Josephs et al., 2012). The findings in the current study extend the findings of our previous work by assessing direct imaging-clinical correlations and showing that the lateral premotor cortex may be playing as strong a role or even a greater role than the supplementary motor area, for the development of AOS. The premotor cortex is critical for the planning of movements, with lateral premotor cortex particularly involved in planning externally cued movements (Goldberg, 1985). The suggestion that the lateral premotor cortex may be playing a greater role than the supplementary motor area would also be in keeping with the fact that striking atrophy of the supplementary motor area is also observed in subjects with progressive supranuclear palsy who do not show AOS (Whitwell et al., 2011). The supplementary motor area may therefore be contributing to the clinical phenotype in PPAOS but does not seem a likely candidate as the/a crucial component of the network that is damaged in PPAOS. The association between AOS and lateral premotor cortex in the entire group could have been masked by the fact that subjects with agrammatic aphasia typically are associated with more severe patterns of imaging abnormalities than PPAOS (Josephs et al., 2012; Josephs et al., 2006).

A previous study that assessed subjects with AOS resulting from stroke implicated damage to the insula as being causative (Dronkers, 1996). Our results did not support this finding, showing that neither atrophy nor hypometabolism in the insula were associated with AOS severity. Another stroke study also did not find any causative relationship between AOS and damage to the insula, and concluded that the insula was previously identified due to confounds of the large size of the overlapping infarcts and the fact that the insula is vulnerable to ischemia in large middle cerebral artery strokes which cause AOS (Hillis et al., 2004). Another region that has been suggested to play a role in the development of AOS in two previous studies is the inferior posterior frontal cortex, namely Broca’s area (Hillis et al., 2004; Rohrer, Rossor, & Warren, 2010). We, however, found that this region correlated to agrammatic aphasia severity, and not AOS severity in PPAOS. In fact, both of these previous studies included subjects with concurrent agrammatic aphasia which could have contributed to their findings. One of these studies assessed regional correlations with neurodegenerative AOS (Rohrer et al., 2010), although they only assessed diadochokinetic rate, whereas the ASRS utilized in our study assesses the severity of 16 different clinical features of AOS, most related to performance on more natural speech tasks, and hence provides a more robust and perhaps more valid test of AOS severity. It is possible however that the planning and programming of speech is supported by a network of inter-connected regions. AOS may thus emerge if the superior premotor cortex, or connections to it are impaired. Indeed, degeneration of frontal regions of the superior longitudinal fasciculus has been associated with the presence of speech distortions in one study (Wilson, Henry, et al., 2010). We did observe weak trends for correlations between AOS and inferior frontal regions, perhaps supporting a network theory.

Aphasia severity was measured using two different tests: the WAB AQ to assess overall aphasia severity and the Token Test to assess aspects of grammatic/syntactic comprehension. Both measures correlated most strongly with FDG hypometabolism in the left inferior triangularis, providing strong evidence that this specific region of Broca’s area is relevant to the development of features of agrammatic aphasia. However, correlations were also observed with hypometabolism in the left pars opercularis, pars orbitalis, middle frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe, with similar patterns observed with volume, suggesting that this network of regions is relevant to the development of agrammatic aphasia. It is important to note also that while agrammatism was a distinguishing feature of the subjects with aphasia, it may not be the only feature of the aphasia. These affected regions do indeed form part of the functionally connected language network that has been defined using resting state fMRI (Turken & Dronkers, 2011). This network defines a set of regions that are thought to subserve many aspects of language function. Functional imaging studies have similarly implicated the left inferior frontal lobe in syntactic comprehension (Caplan, Alpert, & Waters, 1999; Stromswold, Caplan, Alpert, & Rauch, 1996; Wilson, Dronkers, et al., 2010), and a number of studies have identified correlations between syntactic comprehension and volume loss in the left inferior frontal lobe (Amici et al., 2007; Peelle et al., 2008), as well as the middle frontal gyrus (Amici et al., 2007). Other abnormalities observed in agrammatic aphasia, such as reduced speech rate (Ash et al., 2009; Wilson, Henry, et al., 2010), phonetically implausible errors in regular word spelling (Shim, Hurley, Rogalski, & Mesulam, 2012) and word fluency (Rogalski et al., 2011) have also been associated with the left inferior frontal gyrus. More widespread associations have also been observed, with reduced speech rate and grammatical errors found to be associated with the superior temporal (Ash et al., 2009; Wilson, Henry, et al., 2010) and parietal lobes (Rogalski et al., 2011; Wilson, Henry, et al., 2010), supporting our findings of more widespread abnormalities. Notably, our results do not concur with one study that suggested that hypometabolism of the anterior insula was involved in agrammatic aphasia (Nestor et al., 2003). The majority of these previous studies assessed correlations across heterogeneous cohorts of subjects with different variants of PPA, whereas we identified strong correlations within a more homogeneous cohort of subjects with agrammatic aphasia (i.e., excluding subjects with the logopenic and semantic variants of PPA). In addition, the tests we selected allowed the parsing of agrammatic aphasia and AOS, whereas many of the features assessed in previous studies, such as slow speech rate and reduced fluency, could be reduced in subjects with AOS or aphasia.

We demonstrate distinct and non-overlapping regional correlations of measures of AOS and agrammatic aphasia, supporting the suggestion that AOS in PPAOS and agrammatic aphasia are dissociable clinical features that have different neuroanatomical underpinnings. Longitudinal studies will be needed to determine whether the subjects with PPAOS later develop involvement of Broca’s area and hence show features of agrammatic aphasia.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We assess regional brain correlations of agrammatic aphasia and apraxia of speech

Severity of apraxia of speech correlated to volume loss in superior premotor cortex

Aphasia correlated to volume and metabolism of a network of left hemisphere regions

Aphasia correlated most strongly to hypometabolism in the pars triangularis

Agrammatic aphasia and apraxia of speech have non-overlapping regional correlations

Acknowledgments

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

This study was funded by R01-DC010367 from the NIDCD. The sponsor played no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amici S, Brambati SM, Wilkins DP, Ogar J, Dronkers NL, Miller BL, et al. Anatomical correlates of sentence comprehension and verbal working memory in neurodegenerative disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(23):6282–6290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1331-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash S, Moore P, Vesely L, Gunawardena D, McMillan C, Anderson C, et al. Non-Fluent Speech in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. J Neurolinguistics. 2009;22(4):370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Alpert N, Waters G. PET studies of syntactic processing with auditory sentence presentation. Neuroimage. 1999;9(3):343–351. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi E, Vignolo LA. The token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain. 1962;85:665–678. doi: 10.1093/brain/85.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers NF. A new brain region for coordinating speech articulation. Nature. 1996;384(6605):159–161. doi: 10.1038/384159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J. Apraxia of Speech in degenerative neurologic disease. Aphasiology. 2006;20(6):511–527. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR. Motor speech disorders: substrates, differetial diagnois, and management. 2. St Louis, MI: Mosby; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR. Motor speech disorders: substrates, differetial diagnois, and management. 2. St Louis, MI: Mosby; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G. Supplementary motor area structure and function: review and hypothesis. Behav Brain Sci. 1985;8:567–616. [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):335–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart RP, Beach WA, Taylor JR. A case of progressive apraxia of speech and non-fluent aphasia. Aphasiology. 1997;11:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Work M, Barker PB, Jacobs MA, Breese EL, Maurer K. Reexamining the brain regions crucial for orchestrating speech articulation. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 7):1479–1487. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Duffy JR, Smith GE, Knopman DS, Parisi JE, et al. Atypical progressive supranuclear palsy underlying progressive apraxia of speech and nonfluent aphasia. Neurocase. 2005;11(4):283–296. doi: 10.1080/13554790590963004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Fossett TR, Strand EA, Claassen DO, Whitwell JL, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose F18 positron emission tomography in progressive apraxia of speech and primary progressive aphasia variants. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):596–605. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Master AV, et al. Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 5):1522–1536. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Layton KF, Parisi JE, et al. Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 6):1385–1398. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovicich J, Czanner S, Greve D, Haley E, van der Kouwe A, Gollub R, et al. Reliability in multi-site structural MRI studies: effects of gradient non-linearity correction on phantom and human data. Neuroimage. 2006;30(2):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Western Aphasia Battery (Revised) San Antonio, Tx: PsychCorp; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Knibb JA, Woollams AM, Hodges JR, Patterson K. Making sense of progressive non-fluent aphasia: an analysis of conversational speech. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2734–2746. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil MR, Doyle PJ, Wambaugh JL. Apraxia of Speech: a treatable disorder of motor planning and programming. In: Nadeau SE, Gonzalez Rothi LJ, editors. Aphasia and language: theory to practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 221–266. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil MR, Robin RA, Schmidt RA. Apraxia of speech: definition and differential diagnosis. In: McNeil MRE, editor. Clinical management of sensorimotor speech disorders. New York: Thieme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Annals of neurology. 1982;11(6):592–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia--a language-based dementia. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349(16):1535–1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PJ, Graham NL, Fryer TD, Williams GB, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Progressive non-fluent aphasia is associated with hypometabolism centred on the left anterior insula. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 11):2406–2418. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelle JE, Troiani V, Gee J, Moore P, McMillan C, Vesely L, et al. Sentence comprehension and voxel-based morphometry in progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and nonaphasic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurolinguistics. 2008;21(5):418–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Jagust WJ, Furst AJ, Ogar JM, Racine CA, Mormino EC, et al. Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(4):388–401. doi: 10.1002/ana.21451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Thompson CK, Weintraub S, et al. Anatomy of language impairments in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci. 2011;31(9):3344–3350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5544-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD. Apraxia in progressive nonfluent aphasia. J Neurol. 2010;257(4):569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim H, Hurley RS, Rogalski E, Mesulam MM. Anatomic, clinical, and neuropsychological correlates of spelling errors in primary progressive aphasia. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(8):1929–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromswold K, Caplan D, Alpert N, Rauch S. Localization of syntactic comprehension by positron emission tomography. Brain Lang. 1996;52(3):452–473. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turken AU, Dronkers NF. The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Avula R, Master A, Vemuri P, Senjem ML, Jones DT, et al. Disrupted thalamocortical connectivity in PSP: a resting state fMRI, DTI, and VBM study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(8):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Dronkers NF, Ogar JM, Jang J, Growdon ME, Agosta F, et al. Neural correlates of syntactic processing in the nonfluent variant of primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci. 2010;30(50):16845–16854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2547-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, Ogar JM, Dronkers NF, Jarrold W, et al. Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):2069–2088. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]