Abstract

Background

Blood pressure is known to fluctuate widely during hemodialysis; however, little is known about the association between intradialytic blood pressure variability and outcomes.

Study Design

Retrospective observational cohort

Setting & Participants

A random sample of 6,393 adult, thrice-weekly, in-center, maintenance hemodialysis patients dialyzing at 1,026 dialysis units within a single large dialysis organization.

Predictor

Intradialytic systolic blood pressure (SBP) variability. This was calculated using a mixed linear effects model. Peri-dialytic SBP phenomena were defined as starting SBP (regression intercept), systematic change in SBP over the course of dialysis (2 regression slopes), and random intradialytic SBP variability (absolute regression residual).

Outcomes

All-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Measurements

SBPs (n=631,922) measured during hemodialysis treatments (n=78,961) over the first 30 days in study. Outcome data were obtained from the dialysis unit electronic medical record and were considered beginning on day 31.

Results

High (ie, greater than the median) versus low SBP variability was associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.08–1.47). The association between high SBP variability and cardiovascular mortality was even more potent (adjusted HR, 1.32; 85% CI, 1.01–1.72). A dose response trend was observed across quartiles of SBP variability for both all-cause (p=0.001) and cardiovascular (p=0.04) mortality.

Limitations

Inclusion of subjects from a single large dialysis organization, over-representation of African Americans and patients with diabetes and heart failure, and lack of standardized SBP measurements.

Conclusions

Greater intradialytic SBP variability is independently associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm findings and identify means of reducing SBP variability to facilitate randomized study.

Hemodialysis (HD) patients have high rates of mortality, particularly cardiovascular mortality, with cardiovascular death rates 10-fold higher than those of the general population (1, 2). This disproportionate risk has been linked to numerous cardiovascular factors including: 1) blood pressure phenomena such as very low and very high pre-dialysis systolic blood pressures (SBPs) (3–5) and intradialytic hypotension (6, 7); 2) cardiac structural changes such as left ventricular hypertrophy and altered electrical conduction systems (8, 9); 3) neurohormonal imbalances; and 4) autonomic instability (10–12).

Blood pressure variability is one particularly compelling and understudied putative cardiovascular risk factor for the HD population. Dialysis patients are routinely exposed to non-physiologic fluid and osmolar shifts during the dialytic procedure that, combined with impaired counter-regulatory responses, promote more prominent BP changes than are encountered in almost any other clinical circumstance. Evidence from non-dialysis populations has established that greater BP variability is a risk factor for cardiovascular events (13–16), stroke (16), and increased left ventricular hypertrophy (17). Nonetheless, no reported studies have examined whether BP variability during the dialysis procedure itself is associated with adverse patient outcomes.

We undertook the present study to estimate the association between increased intradialytic BP variability and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among thrice-weekly, maintenance HD patients. To do so, we defined BP variability (and other peri-dialytic SBP phenomena) using a recently validated paradigm based on a mixed linear model descriptor. We hypothesized that greater intradialytic BP variability would be associated with both increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

METHODS

Study design

The study cohort was drawn from a random sample of adult (aged ≥18 years) patients who were receiving thrice-weekly, in-center maintenance HD at one large dialysis organization (LDO). Patients entered the cohort between February 7, 2008 and June 29, 2008 and dialyzed at one of 1,026 out-patient units located across a broad geographic distribution of the United States. Because blood pressures immediately following dialysis initiation may fluctuate more widely due to dry weight probing and medication titration, we excluded patients on HD <3 months. In order to remain germane to the majority of US HD patients, we excluded patients who dialyzed <2 or >8 hours. Finally, we excluded patients who died during the 30-day exposure period and those who did not remain enrolled at the LDO until the start of at-risk time (day 31 after study entry). In total, the analytical cohort consisted of 6,393 unique patients. This study was approved by the Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board.

Data collection and description

All data were obtained from the LDO’s electronic medical record and were collected according to the organization’s standard clinical protocols. Demographic data were recorded by unit personnel upon facility intake. Treating nephrologists ascertained co-morbid data through patient interview, examination, and review of the medical record and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Form 2728, and thereafter based on clinical course. Laboratory parameters were measured at entry to the LDO and then on a bimonthly or monthly basis according to organization protocol; all processing was conducted at a single clinical laboratory. Dialytic session data including SBP were recorded on a session-to-session basis. SBP was measured with the patient in the seated position using automated oscillometric devices immediately before, after, and during (typically at 30-minute intervals) all treatment sessions.

Blood pressure data were considered over the first 30 days after study entry (the “exposure period”), which typically encompassed 12 treatments per patient. Pilot data indicated that SBP parameters defined over 30 days were strongly correlated with those defined over 60- and 90-day timeframes; a 30-day period was therefore selected to minimize survivor bias. Because some SBP metrics required a minimum of 3 measurements, we excluded treatments in which SBP was measured <3 times. In total, data from 78,961 dialysis sessions were used to define SBP metrics.

Demographic characteristics (age, race, dialysis vintage, and vascular access type) and co-morbidities (diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, and coronary artery disease) were considered as of cohort entry. Laboratory values (equilibrated Kt/V, albumin, creatinine, calcium, and hemoglobin) were considered as the last value measured during the exposure period. Dialytic session characteristics (session length, post-dialysis weight, and interdialytic weight gain) were considered as the mean value over the exposure period. Prescribed anti-hypertensive medications were not considered since our prior work demonstrated that antihypertensive number, class, and dialyzability status were not significantly associated with intradialytic BP variability.(18)

The co-primary outcomes of interest were death from any cause and death from cardiovascular causes. Date of death and attributed cause of death were recorded in the electronic record by unit staff. Cardiovascular deaths were defined as those attributed to ischemic heart disease, heart failure/pulmonary edema, arrhythmia, valvular defect, and arterial embolism. Patients were considered at-risk for outcome immediately following the exposure period (study day 31) and remained at-risk until death or censoring for transfer of care, transplantation, dialytic modality change, or end of study (February 21, 2009).

Exposure

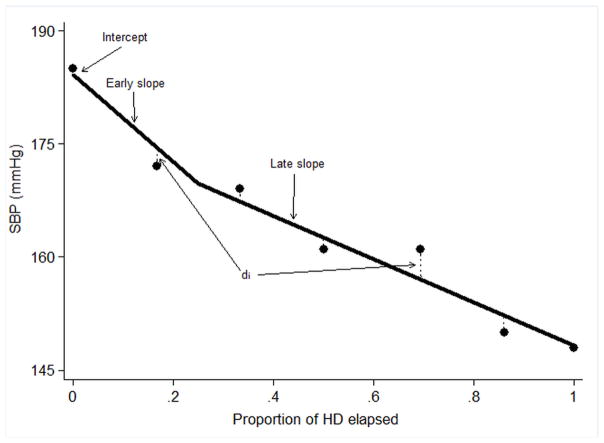

SBP phenomena during the peri-dialytic period were quantified using a mixed linear model as previously described (Fig 1) (18, 19). The model describes measures of the starting SBP, systematic change in SBP over the course of HD, and the random variability in SBP during treatment. Time was considered as a two-slope linear spline which permitted independent descriptions of the linear slopes in SBP during the first 25% of dialysis (early slope) and the latter 75% of dialysis (late slope). Random effects terms were introduced to account for between-patient differences in starting SBP (intercept), early slope, and late slope and for between-treatment differences in intercept within each patient. Under this paradigm, the patient-specific intercept represented the starting SBP, the two patient-specific slopes represented systematic change in SBP; intradialytic SBP variability was represented by the scatter about the fitted blood pressure curve: ie, the absolute vertical distance of predicted minus observed SBP, averaged over treatment and then over patient (absolute SBP residual). Treatment-specific intercepts (within patient) were considered as means over a 30-day period.

Figure 1. Mixed linear systolic blood pressure metric by phase of treatment session.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements during one hypothetical dialysis treatment in one individual (circles). The solid line represents the expected pattern of SBP during the course of a single dialysis treatment and is estimated from a mixed-effects model with main effect terms for the proportion of dialysis elapsed (considered as a 2-slope linear spline with knot at 0.25), random effects intercept terms for subject and treatment, and random effects slope terms for subject. Starting SBP is described as the intercept of the regression line; early slope as the slope of the predicted SBP line over the first 25% of dialysis; late slope as the slope of the predicted SBP line over the latter 75% of dialysis; absolute SBP residual is defined in terms of the absolute value of the vertical distance (dashed lines; di) between each SBP measurement and the predicted value for the corresponding time.

Statistical analysis

Patient and treatment characteristics were described by means, standard deviations, medians, interquartile ranges, and counts and proportions as dictated by data type. Analyses of time-to-death from any cause and time-to-death from cardiovascular causes were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models. The proportionality assumption was tested and confirmed by Schoenfeld residual testing. We conducted unadjusted (containing only the SBP parameters) and adjusted analyses for variables plausibly associated with both exposure and outcome: age, sex, race (black, non-black), dialysis vintage (<3, ≥3y), hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular access type (fistula, graft, catheter), dialysis session length, post-dialysis weight, interdialytic weight gain, creatinine, equilibrated Kt/V, albumin, calcium, and hemoglobin. Specification of continuous covariates (linear versus categorical) was guided by each covariate’s observed association with outcome as assessed by graphical evaluation, Akaike’s Information Criterion, and Martingale residual plots. Based on these analyses, intercept was considered as a categorical variable, and early and late slopes were considered as continuous variables. Missing indicator variables were used to account for data missingness; sensitivity analyses in which missing values were multiply imputed yielded similar findings and are not shown here for simplicity.

Given concerns that pre-terminal disease might alter SBP behavior in the time leading up to death and therefore not be representative of the patient’s blood pressure behavior more broadly, we repeated our analyses with introductions of 30- and 60-day lag periods between the end of the exposure period and the start of at-risk time. Estimates from these models were identical to those from the primary model, and we present only non-lagged analyses here.

Effect modification of the BP variability–mortality association on the basis of diabetes was explored through restriction subgroup analysis; for this analysis, absolute SBP residual was dichotomized at its median. Significance of interaction was assessed by likelihood ratio testing of nested models that did and did not include two-way cross product terms (factor-by-exposure).

To verify the predictive capacity of the mixed linear paradigm, we examined the BP variability–outcomes associations using a parallel BP variability paradigm containing corresponding metrics: predialysis SBP (pre-SBP), postdialysis SBP minus pre-SBP (pre-to-post SBP change), and the standard deviation of intra-dialytic SBP measurements (SBP standard deviation) (Fig S1, available as online supplementary material). Correlations between the SBP metrics under the two descriptive paradigms were examined by scatter plots and Pearson’s correlation. Survival analyses were performed analogously to the primary analysis. Given the similarity of findings, these parallel results are reported in Item S1 as a technical supplement and are not further discussed in the primary manuscript. All analyses were performed using STATA 10.0MP (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Cohort and treatment characteristics

Overall, 6,320 patients underwent a total of 78,961 dialysis treatments during which 631,922 qualifying SBP measurements were recorded. Demographic, clinical, biochemical, and HD session characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 59.7 years, 46.5% were women, 44.2% were black, and 53.3% dialyzed via fistula. Mean dialysis session length was 218 minutes; only 44 patients had mean session lengths >300 minutes and 33 had mean session lengths <150 minutes. Mean interdialytic weight gain was 2.8 kg.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study cohort by quartile of absolute SBP residual.

| Total | Quartile 1 (<7.1 mm Hg) | Quartile 2 (7.1–<8.7 mm Hg) | Quartile 3 (8.7–<10.7 mm Hg) | Quartile 4 (≥10.7 mm Hg) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Participant Characteristics* | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age (y) | 59.7 ± 14.5 | 56.6 ± 15.6 | 59.8 ± 14.5 | 61.0 ± 14.1 | 61.2 ± 13.3 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Black race | 2,818 (44.2%) | 677 (42.6%) | 720 (45.0%) | 729 (45.6%) | 692 (43.4%) | 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Female sex | 2,973 (46.5%) | 604 (38.0%) | 666 (41.5%) | 767 (47.9%) | 936 (58.6%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes | 3,989 (62.4%) | 785 (49.4%) | 919 (57.3%) | 1,077 (67.2%) | 1,208 (75.6%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart failure | 3,284 (51.4%) | 729 (45.9%) | 771 (48.0%) | 859 (53.6%) | 925 (57.9%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 966 (15.1%) | 214 (13.5%) | 237 (14.8%) | 256 (16.0%) | 259 (16.2%) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 3,093 (48.4%) | 713 (44.6%) | 735 (46.0%) | 809 (50.6%) | 836 (52.3%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Dialysis Vintage (<3 y) | 2,293 (36.0%) | 570 (36.0%) | 552 (34.5%) | 563 (35.2%) | 608 (38.2%) | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Vascular Access | <0.001b | |||||

| Fistula | 3,382 (53.2%) | 966 (61.1%) | 905 (56.8%) | 799 (50.2%) | 712 (44.8%) | |

| Graft | 2,016 (31.7%) | 445 (28.2%) | 479 (30.0%) | 535 (33.7%) | 557 (35.1%) | |

| Catheter | 954 (15.0%) | 169 (10.7%) | 210 (13.2%) | 256 (16.1%) | 319 (20.1%) | |

|

| ||||||

| eKt/V | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| eKt/V category | ||||||

| <1.2 | 754 (11.8%) | 184 (11.6%) | 193 (12.0%) | 186 (11.6%) | 191 (12.0%) | |

| ≥1.2 | 4,535 (70.9%) | 1,124 (70.7%) | 1,142 (71.1%) | 1,158 (72.3%) | 1,111 (69.5%) | |

| Missing | 1,104 (17.3%) | 281 (17.7%) | 270 (16.8%) | 258 (16.1%) | 295 (18.5%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Serum albumin catgory | ||||||

| ≤3.5 g/dL | 1,110 (17.4%) | 233 (14.7%) | 264 (16.4%) | 299 (18.6%) | 314 (19.6%) | |

| >3.5–≤4 g/dL | 2,618 (41.0%) | 621 (39.1%) | 643 (40.1%) | 658 (41.1%) | 696 (43.6%) | |

| >4 g/dL | 1,609 (25.1%) | 461 (29.0%) | 435 (27.1%) | 399 (24.9%) | 314 (19.7%) | |

| Missing | 1,056 (16.5%) | 274 (17.2%) | 263 (16.4%) | 246 (15.4%) | 273 (17.1%) | |

|

| ||||||

| SCr (mg/dL) | 9.0 ± 2.9 | 9.2 ± 3.1 | 9.3 ± 2.9 | 8.9 ± 2.7 | 8.5 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| SCr category | ||||||

| Q1: ≤6.9 mg/dL | 1,295 (20.3%) | 322 (20.3%) | 290 (18.1%) | 323 (20.1%) | 360 (22.5%) | |

| Q2: >6.9–≤8.7 mg/dL | 1,329 (20.8%) | 298 (18.7%) | 319 (19.9%) | 351 (21.9%) | 361 (22.6%) | |

| Q3: >8.7–<10.7 mg/dL | 1,235 (19.3%) | 292 (18.4%) | 295 (18.4%) | 331 (20.7%) | 317 (19.9%) | |

| Q4: ≥10.7 mg/dL | 1,289 (20.2%) | 367 (23.1%) | 379 (23.6%) | 304 (19.0%) | 239 (15.0%) | |

| Missing | 1,245 (19.4%) | 310 (19.5%) | 322 (20.0%) | 293 (18.3%) | 320 (20.0%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Serum calcium category | ||||||

| <8.4 mg/dL | 778 (12.2%) | 181 (11.4%) | 177 (11.0%) | 212 (13.2%) | 208 (13.0%) | |

| 8.4–<9.5 mg/dL | 2,978 (46.6%) | 746 (46.9%) | 764 (47.6%) | 725 (45.3%) | 743 (46.5%) | |

| 9.5–<10 mg/dL | 1,359 (21.3%) | 362 (22.8%) | 355 (22.1%) | 342 (21.3%) | 300 (18.8%) | |

| ≥10 mg/dL | 760 (11.9%) | 160 (10.1%) | 188 (11.7%) | 200 (12.5%) | 212 (13.3%) | |

| Missing | 518 (8.1%) | 140 (8.8%) | 121 (7.6%) | 123 (7.7%) | 134 (8.4%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Serum Hb (g/dL) | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Serum Hb category | ||||||

| <9 g/dL | 98 (1.5%) | 34 (2.1%) | 18 (1.1%) | 20 (1.3%) | 26 (1.6%) | |

| 9–<10 g/dL | 267 (4.2%) | 61 (3.8%) | 52 (3.2%) | 76 (4.7%) | 78 (4.9%) | |

| 10–<12 g/dL | 2,854 (44.6%) | 707 (44.5%) | 721 (44.9%) | 726 (45.3%) | 700 (43.8%) | |

| ≥12 g/dL | 3,063 (47.9%) | 744 (46.8%) | 788 (49.1%) | 752 (46.9%) | 779 (48.8%) | |

| Missing | 111 (1.7%) | 43 (2.7%) | 26 (1.6%) | 28 (1.8%) | 14 (0.9%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Session Characteristics** | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Dialysis session length (min) | 218.1 ± 0.4 | 215.3 ± 0.7 | 218.0 ± 0.7 | 219.0 ± 0.8 | 219.9 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Postdialysis weight (kg) | 78.1 ± 0.3 | 75.7 ± 0.5 | 77.7 ± 0.6 | 78.4 ± 0.6 | 80.4 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Interdialytic weight gain (kg)d | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Ultrafiltration rate (ml/h/kg) | 10.6 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.1 | 10.6 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 |

Note: Under Participant Characteristics, unless otherwise noted, values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage) and values for continuous variables are given as mean ± SDs. Under Session Characteristics, values are presented as mean ± robust standard error, with adjustment for multiple measurements made with a sandwich estimator. Conversion factors for units: SCr in mg/dL to μmol/L, ×88.4; serum calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.2495.

N = 6,393, except for race (n=6,381), dialysis vintage (n=6,374), vascular access (n=6,352),

N=78,961, except for postdialysis weight (n=78,218), interdialytic weight gain (n=78,171), and ultrafiltration rate (n=77,831)

P-trend presented for catheter versus non-catheter

Interdialytic weight gain (kg) is essentially synonymous with total ultrafiltration volume (L)

SBP, systolic blood pressure; Q, quartile; SD, standard deviation; SCr, serum creatinine; Hb, hemoglobin; eKt/V, equilibrated Kt/V.

Systolic blood pressure metric

A description of SBP parameters across the cohort is provided in Table 2. Mean intercept was 146.5 mmHg. Mean early slope was −36.4 mmHg/treatment and mean late slope was −10.7 mmHg/treatment; the time-weighted mean of these (i.e., 0.25*early slope + 0.75*late slope) corresponds to a SBP change of −17.1 mmHg/treatment. The mean absolute SBP residual was 9.1 mmHg.

Table 2.

Mixed linear model SBP metrics.

| Metric | Mean ± SD | Median [IQR] |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Random Effects Model Intercept (mmHg) | 146.5 ± 19.8 | 146.4 [133.1 to 159.7] |

|

| ||

| Random Effects Model 2 Slopes | ||

| Early Slope (10 mmHg/treatment)a,b | −36.4 ± 46.4 | −32.7 [−63.0 to −5.8] |

| Late Slope (10 mmHg/treatment)a,b | −10.7 ± 16.7 | −9.6 [−20.7 to 0.4] |

|

| ||

| Random Effects Model Absolute SBP Residual (mmHg) | 9.1 ± 2.9 | 8.7 [7.1 to 10.7] |

Negative values indicate a reduction in SBP over the course of treatment

Expressed as the change extrapolated over a full dialysis session

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Blood pressure variability and cohort characteristics

Demographic, clinical, biochemical, and HD session characteristics across quartiles of absolute SBP residual are shown in Table 1. Patients with higher absolute SBP residuals were more likely to be older, female, to have diabetes, heart failure, and coronary artery disease, to be dialyzed via catheter, and to have longer dialysis session lengths, higher post-dialysis weights, and larger amounts of interdialytic weight gain. There was no association of absolute SBP residual with race, dialysis vintage, equilibrated Kt/V, serum calcium, serum hemoglobin, or ultrafiltration rate.

Associations between BP variability and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

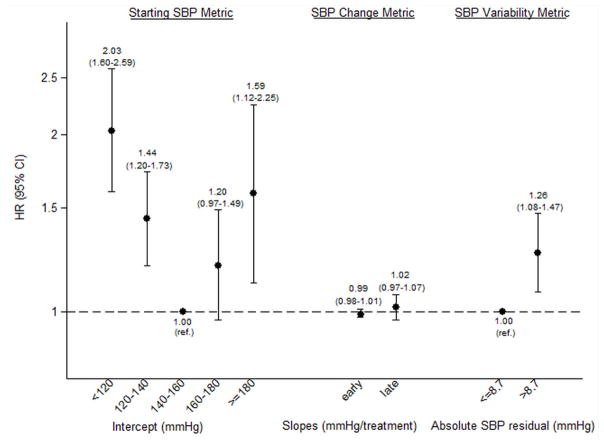

Overall, 779 deaths occurred during 5,019 patient-years of at-risk time; 276 of these deaths (35%) were attributed to cardiovascular causes. Median at-risk time was 318 days. Greater intradialytic SBP variability was associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality. In analysis adjusted only for intercept, early slope, and late slope, the hazard ratio (HR) for high absolute SBP residual (>8.7 mmHg; the cohort median) versus low absolute SBP residual was 1.51 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30–1.76; p<0.001). Upon multivariable adjustment for other potential confounders, the HR was attenuated, but remained statistically significant: 1.26 (95% CI, 1.08–1.47; p=0.004) (Fig 2A). Estimates were numerically more potent among diabetics than non-diabetics (HRs of 1.37 [95% CI, 1.13–1.66] vs. 1.02 [95% CI, 0.77–1.35], respectively), although test for interaction was non-significant (p=0.1).

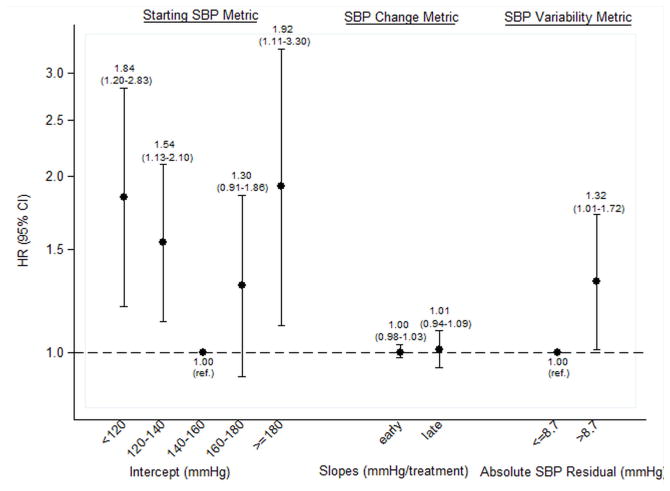

Figure 2. Adjusted associations between systolic blood pressure (SBP) metrics and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Panel A shows all-cause mortality, and Panel B shows cardiovascular mortality. Estimates for early and late slope are presented per 10 mmHg/treatment increment; all other estimates are presented as per category shown. Estimates in each panel are adjusted for one another as well as for age, sex, race (black, non-black), dialysis vintage (<3, ≥3 y), hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular access type (fistula, graft, catheter), delivered dialysis session length, post-dialysis weight, interdialytic weight gain (≤1.5, >1.5–3, >3–4, >4 kg, missing), creatinine (quartiles, missing), equilibrated Kt/V (<1.2, ≤1.2, missing), albumin (≤3.5, >3.5–4, >4 g/dL, missing), calcium (<8.4, 8.4–<9.5, 9.5–<10, ≥10 mg/dL, missing), hemoglobin (<9, 9–<10, 10–<12, ≥12 g/dL, missing).

To evaluate for a dose-response trend, we examined absolute SBP residual in quartiles. The magnitude of association between absolute SBP residual and all-cause mortality was incrementally greater across quartiles (Table 3). We also considered absolute SBP residual, scaled to its observed standard deviation, as a continuous predictor of outcome (Table 4). Each 3 mmHg increment in absolute SBP residual was associated with an adjusted HR for all-cause mortality of 1.18 (95% CI, 1.09–1.28; p<0.001).

Table 3.

Associations between quartiles of absolute SBP residual and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

| (mmHg) | All-cause mortality | Cardiovascular mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI)a | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | Unadjusted HR (95% CI)a | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | |

| Absolute SBP Residual | ||||

| Q1: <7.1 mm Hg | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Q2: 7.1–<8.7 mm Hg | 1.08 (0.87–1.34) | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) | 1.03 (0.72–1.48) | 0.96 (0.66–1.40) |

| Q3: 8.7–<10.7 mm Hg | 1.37 (1.11–1.69) | 1.12 (0.91–1.40) | 1.38 (0.97–1.95) | 1.19 (0.83–1.71) |

| Q4: ≥10.7 mm Hg | 1.84 (1.49–2.27) | 1.42 (1.13–1.77) | 1.74 (1.22–2.48) | 1.43 (0.98–2.09) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.04 |

Absolute SBP Residual parameter estimates adjusted for SBP intercept and SBP slopes.

Absolute SBP Residual parameter estimates adjusted for SBP intercept and SBP slopes as well as for age, sex, race (black, non-black), dialysis vintage (<3, ≥3y), hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular access type (fistula, graft, catheter), delivered dialysis session length, postdialysis weight, interdialytic weight gain (≤1.5, >1.5–3, >3–4, >4 kg, missing), creatinine (quartiles, missing), equilibrated Kt/V (<1.2, ≥1.2, missing), albumin (≤3.5, >3.5–4, >4 g/dL, missing), calcium (<8.4, 8.4–<9.5, 9.5–<10, ≥10 mg/dL, missing), hemoglobin (<9, 9–<10, 10–<12, ≥12 g/dL, missing).

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; Q, quartile; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Association of continuous BP variability metric and outcomes.

| All-cause mortality | Cardiovascular mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted HRa (95% CI) | Adjusted HRb (95% CI) | Unadjusted HRa (95% CI) | Adjusted HRb (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Absolute SBP residual (per 3 mmHg) | 1.29 (1.21–1.39) | 1.18 (1.09–1.28) | 1.33 (1.18–1.50) | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) |

|

| ||||

| Early slopec | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

|

| ||||

| Late slopec | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) |

|

| ||||

| Intercept | ||||

| <120 mmHg | 2.29 (1.82–2.90) | 2.07 (1.62–2.63) | 2.14 (1.42–3.22) | 1.89 (1.24–2.90) |

| 120–<140 mmHg | 1.55 (1.29–1.85) | 1.47 (1.22–1.76) | 1.64 (1.21–2.22) | 1.59 (1.17–2.17) |

| 140–<160 mmHg | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 160–<180 mmHg | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 1.17 (0.94–1.45) | 1.12 (0.79–1.60) | 1.24 (0.87–1.78) |

| ≥180 mmHg | 1.18 (0.83–1.68) | 1.46 (1.02–2.08) | 1.45 (0.84–2.49) | 1.70 (0.98–2.95) |

SBP parameter estimates adjusted for one another only.

SBP parameter estimates adjusted for one another as well as for age, sex, race (black, non-black), dialysis vintage (<3, ≥3 y), hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular access type (fistula, graft, catheter), delivered dialysis session length, postdialysis weight, interdialytic weight gain (≤1.5, >1.5–3, >3–4, >4 kg, missing), creatinine (quartiles, missing), equilibrated Kt/V (<1.2, ≥1.2, missing), albumin (≤3.5, >3.5–4, >4 g/dL, missing), calcium (<8.4, 8.4–<9.5, 9.5–<10, ≥10 mg/dL, missing), hemoglobin (<9, 9–<10, 10–<12, ≥12 g/dL, missing).

HRs are reported per 10 mmHg/treatment

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

SBP variability was even more potently associated with cardiovascular mortality. High SBP residual (>8.7 mmHg; the cohort median) was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality compared to low absolute SBP residual (adjusted HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.01–1.72; p=0.04) (Fig 2B). Larger absolute SBP residual quartiles were associated with incrementally greater hazards of cardiovascular mortality (Table 3). When examined as a continuous predictor, each 3 mmHg increment in absolute SBP residual was associated with an adjusted HR of 1.26 (95% CI, 1.11–1.43; p<0.001) (Table 4).

We observed j-shaped associations between intercept and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (Table 4, Figs 2A and 2B). The risk of low intercept was greater than for high intercept. Early and late slopes were not independently associated with either all-cause or cardiovascular mortality.

DISCUSSION

In non-dialysis populations, short-term BP variability is associated with cardiovascular risk and mortality. Despite exceptionally high rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the dialysis population and dramatic BP lability incurred as a result of the dialysis procedure, to our knowledge no prior study has examined the association between BP variability during dialysis and adverse outcomes. In this report, we show that greater intradialytic BP variability is associated with a greater risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Reassuring to its validity, this finding was robust across two different paradigms measuring BP variability.

Numerous studies in non-dialysis populations have linked BP variability to cardiovascular mortality (13, 16, 20) and to cardiovascular morbidities such as atherosclerosis (14, 15), cerebrovascular events (16, 21), and increased left ventricular mass (17). Kikuya demonstrated a 2.5-fold greater rate of cardiovascular mortality among subjects in the highest BP variability quintile (13), and Sander showed that greater BP variability is an independent predictor of carotid intima-to-medial thickness progression and associated cardiovascular events(15). Findings in animal models suggest that these associations may be causal.(22–24) For example, in rodent models, sinoaortic denervation was used to induce increases in short-term BP variability without affecting average blood pressure. Denervated rats developed bi-ventricular hypertrophy (22) and accelerated atheromatous progression compared to sham-operated controls (23, 24). More recently, Di Iorio demonstrated an association between visit-to-visit BP variability and mortality in a chronic kidney disease population, supporting the notion that SBP fluctuations may be particularly detrimental to patients with decreased kidney function (25).

BP variability is potentially of even greater significance among HD patients than among other populations. During HD, patients are routinely exposed to rapid fluid and osmolar shifts that promote random blood pressure fluctuations. Cardiomyopathy, impliable vasculature, autonomic neuropathy, and neurohormonal imbalance—all highly prevalent among HD patients— may serve to amplify such fluctuations. These physiological factors also impair the maintenance of consistent end-organ perfusion in the setting of rapid downward and upward blood pressure fluctuations, thereby subjecting patients to alternating periods of tissue hypoxia and capillary shear stress that may lead to further organ damage. Therefore, the observed association—that greater intradialytic BP variability is associated with greater risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among dialysis patients—should not be surprising. Additionally, our finding that BP variability is more potently associated with cardiovascular compared to all-cause mortality is consistent with this physiological construct.

Other studies have examined links between longitudinal blood pressure behavior and outcomes among dialysis patients, but the physiological constructs considered have varied widely across such studies. For example, absent nocturnal blood pressure dipping (26, 27), greater variability in pre-SBP from one treatment to the next (interdialytic BP variability) (28–30), and an increase in SBP from pre-to-post HD (31, 32) have all been associated with increased mortality risk. However, to our knowledge no prior study has examined the association of outcomes with BP variability during the HD treatment itself. In a prior analysis, our group investigated factors associated with intradialytic BP variability and found that higher ultrafiltration rate and volume, older age, and longer vintage were associated with greater BP variability, but that study was not powered to consider clinical outcomes.(18)

Strengths of our study include its large, nationally representative cohort, the use of standardized protocols for data collection (particularly SBP measurements) across dialysis units, and the demonstration of the BP variability–outcome association using 2 different BP variability metric paradigms. Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting our results. As with all retrospective cohort studies, bias may influence results despite our best efforts to control for confounding. To minimize the risk of confounding, we adjusted estimates for variables plausibly associated with both mortality and BP variability. We did not to include anti-hypertensive medications since our prior work demonstrated that antihypertensive number, class, and dialyzability status were not significantly associated with intradialytic BP variability.(18) Second, our study considered data from US HD units from a single LDO, and the cohort contained a higher proportion of blacks, patients with diabetes, and patients with heart failure compared to the general US dialysis population. Such factors must be considered carefully when generalizing our findings to the broader HD population, particularly since the higher prevalence of heart failure in our cohort may have influenced SBP patterns. Additionally, we restricted analyses to patients dialyzing thrice weekly for times between 2.0 and 8.0 hours; thus, our results should not be extrapolated to patients dialyzing under different paradigms. Finally, we used dialysis machine-measured SBPs to best simulate clinical practice conditions and hence generalizability of our results; however, differing machine calibrations may have introduced misclassification bias. Reassuringly, such misclassification bias should bias our results toward the null, rendering our estimates conservative. Similarly, underlying vascular disease or prior access surgeries may lead to erroneous SBP measurements thus affecting our variability metrics.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that greater intradialytic BP variability is associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm and generalize findings, assess causation, and identify means of manipulating BP variability so as to facilitate randomized study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank DaVita Clinical Research for providing data for this study. DaVita Clinical Research had no role in the design or implementation of this study, nor on the decision to publish.

Support: This work was supported by grants DK093159-01 (to JEF), DK083514 (to TS), and DK079056 (to SMB), all from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); and CRP11680033 (to JKI) and 12SDG11670032 (to TIC), both from the American Heart Association. DaVita provided data for the project. The NIH/NIDDK, American Heart Association, and DaVita had no roles in the design or analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr Brunelli has served on advisory boards for Amgen and CB Fleet and has received speaking honoraria from Fresenius Medical Care; his spouse is an employee at AstraZeneca. The other authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Figure S1: Observed SBP metric by phase of treatment session.

Item S1: Technical supplement.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_____) is available at www.ajkd.org

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004 May;15(5):1307–15. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000123691.46138.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998 Nov;32(5 Suppl 3):S112–9. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zager PG, Nikolic J, Brown RH, et al. “U” curve association of blood pressure and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Medical Directors of Dialysis Clinic, Inc. Kidney Int. 1998 Aug;54(2):561–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers OB, Adams C, Rohrscheib MR, et al. Age, race, diabetes, blood pressure, and mortality among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Nov;21(11):1970–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Port FK, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Wolfe RA, et al. Predialysis blood pressure and mortality risk in a national sample of maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999 Mar;33(3):507–17. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton JO, Jefferies HJ, Selby NM, McIntyre CW. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: determinants and associated outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 May;4(5):914–20. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03900808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoji T, Tsubakihara Y, Fujii M, Imai E. Hemodialysis-associated hypotension as an independent risk factor for two-year mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2004 Sep;66(3):1212–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paoletti E, Specchia C, Di Maio G, et al. The worsening of left ventricular hypertrophy is the strongest predictor of sudden cardiac death in haemodialysis patients: a 10 year survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004 Jul;19(7):1829–34. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Nov;32(5):1454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Converse RL, Jacobsen TN, Jost CM, et al. Paradoxical withdrawal of reflex vasoconstriction as a cause of hemodialysis-induced hypotension. J Clin Invest. 1992 Nov;90(5):1657–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI116037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavalcanti S, Severi S, Chiari L, et al. Autonomic nervous function during haemodialysis assessed by spectral analysis of heart-rate variability. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997 Apr;92(4):351–9. doi: 10.1042/cs0920351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelosi G, Emdin M, Carpeggiani C, et al. Impaired sympathetic response before intradialytic hypotension: a study based on spectral analysis of heart rate and pressure variability. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999 Jan;96(1):23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Ohokubo T, et al. Prognostic significance of blood pressure and heart rate variabilities: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2000 Nov;36(5):901–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sander D, Klingelhöfer J. Diurnal systolic blood pressure variability is the strongest predictor of early carotid atherosclerosis. Neurology. 1996 Aug;47(2):500–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sander D, Kukla C, Klingelhöfer J, Winbeck K, Conrad B. Relationship between circadian blood pressure patterns and progression of early carotid atherosclerosis: A 3-year follow-up study. Circulation. 2000 Sep;102(13):1536–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pringle E, Phillips C, Thijs L, et al. Systolic blood pressure variability as a risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly hypertensive population. J Hypertens. 2003 Dec;21(12):2251–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verdecchia P, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, et al. Prognostic significance of blood pressure variability in essential hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 1996 Feb;1(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flythe JE, Kunaparaju S, Dinesh K, Cape K, Feldman HI, Brunelli SM. Factors associated with intradialytic systolic blood pressure variability. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Mar;59(3):409–18. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinesh K, Kunaparaju S, Cape K, Flythe JE, Feldman HI, Brunelli SM. A model of systolic blood pressure during the course of dialysis and clinical factors associated with various blood pressure behaviors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011 Nov;58(5):794–803. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickering TG, James GD. Ambulatory blood pressure and prognosis. J Hypertens Suppl. 1994 Nov;12(8):S29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Gattobigio R, Rapicetta C, Reboldi G. Impact of blood pressure variability on cardiac and cerebrovascular complications in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2007 Feb;20(2):154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Vliet BN, Hu L, Scott T, Chafe L, Montani JP. Cardiac hypertrophy and telemetered blood pressure 6 wk after baroreceptor denervation in normotensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1996 Dec;271(6 Pt 2):R1759–69. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.6.R1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasaki S, Yoneda Y, Fujita H, et al. Association of blood pressure variability with induction of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rats. Am J Hypertens. 1994 May;7(5):453–9. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eto M, Toba K, Akishita M, et al. Reduced endothelial vasomotor function and enhanced neointimal formation after vascular injury in a rat model of blood pressure lability. Hypertens Res. 2003 Dec;26(12):991–8. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Iorio B, Pota A, Sirico ML, et al. Blood pressure variability and outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012 Sep; doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Covic A, Goldsmith DJ, Covic M. Reduced blood pressure diurnal variability as a risk factor for progressive left ventricular dilatation in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000 Apr;35(4):617–23. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ertürk S, Ertuğ AE, Ateş K, et al. Relationship of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring data to echocardiographic findings in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996 Oct;11(10):2050–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tozawa M, Iseki K, Yoshi S, Fukiyama K. Blood pressure variability as an adverse prognostic risk factor in end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999 Aug;14(8):1976–81. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.8.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunelli SM, Thadhani RI, Lynch KE, et al. Association between long-term blood pressure variability and mortality among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008 Oct;52(4):716–26. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Iorio B, Di Micco L, Torraca S, et al. Variability of blood pressure in dialysis patients: a new marker of cardiovascular risk. J Nephrol. 2012 Mar;:0. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inrig JK, Oddone EZ, Hasselblad V, et al. Association of intradialytic blood pressure changes with hospitalization and mortality rates in prevalent ESRD patients. Kidney Int. 2007 Mar;71(5):454–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inrig JK, Patel UD, Toto RD, Szczech LA. Association of blood pressure increases during hemodialysis with 2-year mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: a secondary analysis of the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Wave 2 Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Nov;54(5):881–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.