Abstract

Background & Aims

There is a clinical need for methods that can quantify regional hepatic function noninvasively in patients with cirrhosis. Here we validate the use of 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-galactose (FDGal) PET/CT for measuring regional metabolic function for this purpose and apply the method to test the hypothesis of increased intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity in cirrhosis.

Methods

Nine cirrhotic patients underwent dynamic liver FDGal PET/CT with blood samples from a radial artery and liver vein. Hepatic blood flow was measured by indocyanine green infusion/Fick’s principle. From blood measurements, hepatic systemic clearance (Ksyst, l blood/min) and hepatic intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km, l blood/min) of FDGal were calculated. From PET data, hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal in liver parenchyma (Kmet, ml blood/ml liver tissue/min) was calculated. Intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity was evaluated in terms of coefficient of variation (CoV, %) using parametric images of Kmet.

Results

Mean approximation of Ksyst to Vmax/Km was 86% which validates the use of FDGal as PET tracer of hepatic metabolic function. Mean Kmet was 0.157 ml blood/ml liver tissue/min, which was lower than 0.274 ml blood/ml liver tissue/min previously found in healthy subjects (p <0.001) in accordance with decreased metabolic function in cirrhotic livers. Mean CoV for Kmet in liver tissue was 24.4% in patients and 14.4% in healthy subjects (p <0.0001). The degree of intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity correlated positively with HVPG (p <0.05).

Conclusions

A 20 min dynamic FDGal PET/CT with arterial sampling provides an accurate measure of regional hepatic metabolic function in patients with cirrhosis. This is likely to have clinical implications for assessment of patients with liver disease as well as treatment planning and monitoring.

Keywords: Liver metabolism, Galactose, Positron emission tomography, Molecular imaging, Clearance

Introduction

It has become increasingly evident that liver cirrhosis is not necessarily a static endpoint of parenchymal liver disease but can indeed be dynamic and potentially reversible. This has, together with the increasing use of local treatments for e.g. liver tumours in patients with cirrhosis, led to an increased clinical demand for noninvasive methods that can quantify stiffness and metabolic functions of the liver [1]. It is also of clinical interest to be able to predict remnant liver function following e.g. partial liver resection by estimating regional-to-global liver function, especially in patients with parenchymal liver disease [2]. In Japan, hepatic scintigraphy with measurements of the asialoglycoprotein receptor density with 99mTc-galactosylneoalbumin (99mTc-GSA) is used for assessment of liver function but the method is not approved in Europe or USA [2]. Another method is hepatobiliary scintigraphy (and more recently single photon emission computer tomography, SPECT) with 99mTc-mebrofenin, a substrate that is taken up from blood by hepatocytes and excreted unmetabolized into bile [2]. Hepatic uptake and excretion of 99mTc-mebrofenin is however impaired by hypoalbuminemia and high levels of plasma bilirubin as well as impaired bile flow [2]. Furthermore, scintigraphy suffers from poor spatial and temporal resolutions compared to e.g. positron emission tomography (PET).

We recently developed a molecular imaging method for in vivo quantification of hepatic galactokinase capacity using dynamic PET/CT and the galactose analogue 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-galactose (FDGal) [3–5]; the galactokinase enzyme metabolizes galactose and analogues hereof and is almost exclusively found in the liver. The capacity of the liver to remove intravenously injected galactose is measured in the galactose elimination capacity (GEC) test [6,7]. The GEC test yields as a measure of global metabolic liver function and provides prognostic information for patients with acute [8,9] and chronic [10,11] liver disease as well as for patients undergoing hepatic resection [12]. However, the GEC test does not provide any information on potential intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity. FDGal PET/CT offers a unique possibility for studying regional variations in metabolic function in terms of hepatic galactokinase activity [5]. In our study in healthy subjects, the FDGal PET/CT measurements were validated against direct measurements of hepatic removal kinetics of galactose and FDGal by blood measurements from an artery and liver vein [5]. The aim of the present study was to validate the use of FDGal PET/CT for noninvasive 3D quantification of regional hepatic galactokinase capacity in patients with liver cirrhosis and to apply the method to test the hypothesis of an increased heterogeneity of galactokinase capacity in liver cirrhosis.

Patients and methods

Study design

A 60 min dynamic liver FDGal PET/CT with blood sampling from a radial artery and a liver vein was performed with simultaneous determination of hepatic blood flow by indocyanine green infusion/Fick’s principle. Blood concentration measurements of FDGal in arterial and liver venous blood and the hepatic blood flow measurements were used to validate FDGal as a PET/CT tracer for galactokinase capacity. The FDGal PET/CT scan and arterial blood samples were used to measure galactokinase capacity in liver parenchyma as well as metabolic heterogeneity.

Patients

Ten patients with liver cirrhosis were included in the study; one patient was excluded due to technical problems with the PET/CT scanner causing the experiment to be cancelled. The patients were included from the outpatient clinic at Department of Medicine V (Hepatology/Gastroenterology), Aarhus University Hospital. Patients referred to the department for hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement by liver vein catheterization were offered to participate in the study. Patients were instructed not to take any food or drugs for 8 hours before the study but were allowed to drink water. None of the patients received medical treatment for portal hypertension at the time of the study. Patient characteristics are given in Table 1. No patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were included as we know that HCC nodules may have increased FDGal accumulation [13].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Subject | Gender / Age (years) |

Body weight (kg) |

Etiology | Albumin (g/l plasma) |

Bilirubin µmol/l plasma) |

ALT (U/l plasma) |

ALP (U/l plasma) |

Child-Pugh class |

MELD Score |

Normalized GEC |

HVPG (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male / 61 | 70 | Alcohol | 43 | 14 | 43 | n.a. | A | 6 | 0.62 | 12.0 |

| 2 | Male / 66 | 86 | Alcohol | 37 | 11 | 28 | 80 | B | 8 | 0.60 | 18.5 |

| 3 | Female / 60 | 82 | Cryptogenic | 40 | 12 | 39 | 96 | A | 8 | 0.48 | 19.9 |

| 4 | Male / 57 | 79 | Alcohol + HCV | 35 | 18 | 121 | 155 | B | 8 | 0.45 | 30.5 |

| 5 | Female / 71 | 83 | Cryptogenic | 41 | 17 | n.a. | n.a. | A | 8 | 0.65 | 23.5 |

| 6 | Male / 50 | 93 | Alcohol | 36 | 11 | 23 | 98 | B | 8 | 0.51 | 22.0 |

| 7 | Male / 62 | 90 | Alcohol | 35 | 10 | 14 | 91 | B | 10 | 0.55 | 22.7 |

| 8 | Male / 65 | 62 | Alcohol | 33 | 20 | 21 | 104 | B | 13 | 0.49 | 24.0 |

| 9 | Male / 43 | 70 | Alcohol | 40 | 4 | 13 | 91 | A | 8 | 0.81 | 18.0 |

Albumin reference interval 36–45 g/l plasma; Bilirubin reference interval 5–25 µmol/l plasma; ALT, alanine aminotransferase (reference interval 10–70 units/l plasma); ALP, alkaline phosphatase (reference interval 35–105 units/l plasma); n.a., not available; Child-Pugh class, patients were scored according to the Child-Pugh classification [14]; Normalized GEC, galactose elimination capacity (GEC) normalized to expected value from a healthy subject of same body weight, age, and sex; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Ethics

The study was approved by The Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics and conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients. The mean radiation dose received by each subject was 4 mSv. No complications to the procedures were observed.

Galactose elimination capacity test

As part of standard clinical work-up, a GEC test was performed in all patients. The GEC provides an estimate of the maximum removal rate of galactose (mmol/min) for the whole liver, i.e. global galactokinase capacity [6,7]. The result is normalized to provide an index of the metabolic function of the liver as a fraction of the expected value for a healthy individual of the same sex, age, and body weight (normalized GEC).

Catheterizations

Small catheters were placed in a cubital vein in both arms and in a radial artery. For blood sampling and HVPG measurement, a 6F catheter (Cook Catheter, Bjaeverskov, Denmark) was placed in a liver vein in the right liver lobe via an introducer catheter in the right femoral vein. The HVPG was calculated as the difference between pressures measured in the wedged and free position in the liver vein.

Hepatic blood flow

An intravenous infusion of indocyanine green (Hyson, Wescott and Dunning, Baltimore, MD, USA) was started 90 minutes before the PET study. During the PET study, four pairs of blood samples (5 ml each) were collected from the radial artery and the liver vein for spectrophotometric determination of plasma concentrations of indocyanine green [15,16]. Good approximation to steady state concentrations was obtained in each subject and individual mean concentrations from the artery and liver vein were used to calculate an individual mean hepatic blood flow (F, l blood/min) according to Fick’s principle with adjustment for individual hematocrit values [17].

FDGal PET/CT and blood measurements

The subjects were placed on their back in a 64-slice Siemens Biograph TruePoint PET/CT camera (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). A topogram of the abdomen was performed for optimal positioning of the liver within the 21.6 cm transaxial field-of-view of the PET camera followed by low-dose CT scan (50 effective mAs with CAREDose4D, 120 kV, pitch 0.8, slice thickness 5 mm) for definition of anatomical structures and attenuation correction of PET data. A bolus of 100 MBq FDGal in 10 ml saline was administered intravenously during the initial 15 seconds of a 60 min dynamic PET recording. FDGal was produced in our own radiochemistry laboratory (radiochemical purity ≥97%) [18]. PET data were reconstructed using iterative processing and a time-frame structure of 18 × 5, 15 × 10, 4 × 30, 4 × 60, and 10 × 300 seconds (total 60 min) and corrected for radioactive decay back to start of the recording.

During the PET study, arterial and liver vein blood samples (0.5 ml) were collected manually at 18 × 5, 6 × 10, 3 × 20, 3 × 60, 1 × 120, 1 × 240, 1 × 360, and 4 × 600 seconds for determination of FDGal blood concentrations. Radioactivity concentrations (kBq/ml blood in A, arterial and V, liver venous blood) were measured in a well counter (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT, USA) and corrected for radioactive decay back to start of the PET recording.

Validation of FDGal as a PET tracer for galactokinase capacity

The hepatic extraction fraction of FDGal was calculated as E = (A−V)/A using mean values of A and V from blood samples collected in the interval 6–20 min after the FDGal injection (quasi-steady state metabolism) and corrected for a mean splanchnic transit time of 1 min [19]. The intrinsic clearance of hepatic FDGal metabolism (Vmax/Km; l blood/min) was calculated as [20]

| (1) |

The hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal (Ksyst, l blood/min) was calculated as [20]

| (2) |

For the FDGal PET/CT method to provide a measurement of galactokinase capacity, Ksyst must be predominantly enzyme-determined [5]. For Vmax/Km << F, Ksyst approximates Vmax/Km and is predominantly enzyme-determined; for Vmax/Km >> F, Ksyst approximates F and is predominantly flow-determined [20]. The approximations were assessed quantitatively as the ratios Ksyst/(Vmax/Km) and Ksyst/F, respectively.

Image analysis

A volume-of-interest was drawn in the right liver lobe using the fused PET/CT images and the time-course of radioactivity concentration in liver tissue (Bq/ml liver tissue versus time in minutes) in this volume-of-interest was extracted. The hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal in the liver (Kmet, ml blood/ml liver tissue/min) was determined according to the Gjedde-Patlak representation of data [21,22] assuming irreversible metabolism of FDGal [3,5]. Because this is the first study in cirrhotic patients, we performed the PET recording for 60 min. A detailed analysis of data showed that data from 6–20 min after FDGal administration were optimal for the Gjedde-Patlak analysis similar to what we found in healthy subjects [5]. The volume-of-interest based analysis was used to determine the optimal time period and to verify that the hepatic FDGal metabolism is irreversible before proceeding to the image-based analysis of functional heterogeneity from parametric images of Kmet.

Parametric images of Kmet were created by applying the Gjedde-Patlak analysis to each voxel in the dynamic PET recordings using data from 6–20 min after FDGal administration and the time-course of FDGal in arterial blood as input function. Parametric images thus yield Kmet values for each voxel during quasi-steady state metabolism. The parametric images were used to assess metabolic heterogeneity within the liver in terms of the coefficient-of-variation (CoV) for Kmet.

For comparison, parametric images were created from dynamic FDGal PET/CT data from healthy subjects collected using the same PET/CT protocol as in the present study [5]; in Table 2, data from 8 healthy subjects are included but due to technical problems with one set of PET/CT files, parametric images could only be created for 7 healthy subjects.

Table 2.

Hepatic removal kinetics of FDGal in patients with liver disease.

| Subject |

Kmet (ml blood/ml liver tissue/min) |

Metabolic heterogeneity in terms of CoV of Kmet |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.166 ± 0.005 | 20.0 % |

| 2 | 0.197 ± 0.002 | 19.7 % |

| 3 | 0.196 ± 0.002 | 25.8 % |

| 4 | 0.150 ± 0.001 | 29.9 % |

| 5 | 0.159 ± 0.002 | 23.5 % |

| 6 | 0.121 ± 0.002 | 29.8 % |

| 7 | 0.149 ± 0.002 | 26.1 % |

| 8 | 0.145 ± 0.002 | 22.0 % |

| 9 | 0.199 ± 0.002 | 22.9 % |

| Mean ± SE | 0.157 ± 0.001* | 24.4 ± 3.8* |

| Corresponding values from healthy subjects (from [5]) | ||

| Mean (range) | 0.274 (0.213–0.342) | 14.4 (9.2–17.9) |

Kmet, hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal calculated from volume-of-interest based analysis of PET data.

CoV, coefficient-of-variation calculated as the standard deviation of Kmet in liver tissue divided by the mean Kmet.

Individual values for patients are given as estimate ± the standard error of the estimate; mean ± SE, weighted mean ± standard error of the weighted mean.

Bottom row shows data from 8 healthy subjects as mean (range) [5].

p <0.001 when compared to the healthy subjects (Student’s t-test).

Statistical analysis

Calculation of Kmet of FDGal from the PET-data, as defined by the Gjedde-Patlak relation (linear regression), employed maximum likelihood estimation. Individual data are given as mean ± standard error of the estimate. Population means were calculated as the weighted mean of the individual estimates using the inverse estimated squared standard errors as weight. Comparisons between mean values from patients and healthy subjects were made using Student’s t-test; p <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Correlation between CoV and HVPG was tested by the Pearson productmoment correlation coefficient, r, with p <0.05 considered to indicate a statistically significant correlation.

Results

Hepatic blood flow

Mean hepatic blood flow was 0.95 l blood/min (range, 0.75–1.50 l blood/min), which was not significantly different from the mean value of 0.94 l blood/min (range, 0.70–1.76 l blood/min) found in healthy subjects [5] (p >0.30).

Validation of FDGal as a tracer for measurement of galactokinase capacity

Mean Vmax/(FKm) was 0.28 (range, 0.23–0.41) which means that the hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal is enzyme-dependent and validates the use of hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal as a measure of enzymatic capacity [20]. In accordance with this, the mean approximation of Ksyst to Vmax/Km was 86% (range, 82–90%). This makes FDGal an ideal tracer for in vivo measurements of hepatic galactokinase capacity by dynamic PET/CT in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and we could thus proceed with FDGal as a tracer for measurements of regional galactokinase capacity.

FDGal PET/CT of regional hepatic galactokinase capacity and metabolic heterogeneity

The volume-of-interest based analysis of the dynamic PET/CT data yielded linear Gjedde-Patlak plots for all patients in agreement with irreversible metabolic trapping of FDGal; this forms the basis for generating parametric images (see below). Individual values of Kmet are given in Table 2; the mean value of 0.157 ml blood/ml liver tissue/min (range, 0.121–0.199) was significantly lower than the mean Kmet of 0.274 l blood/l liver tissue/min (range, 0.213–0.342) previously found in healthy subjects [5] (p <0.001). The PET measure of the metabolic capacity per volume liver tissue was thus significantly lower in the patients than in healthy subjects.

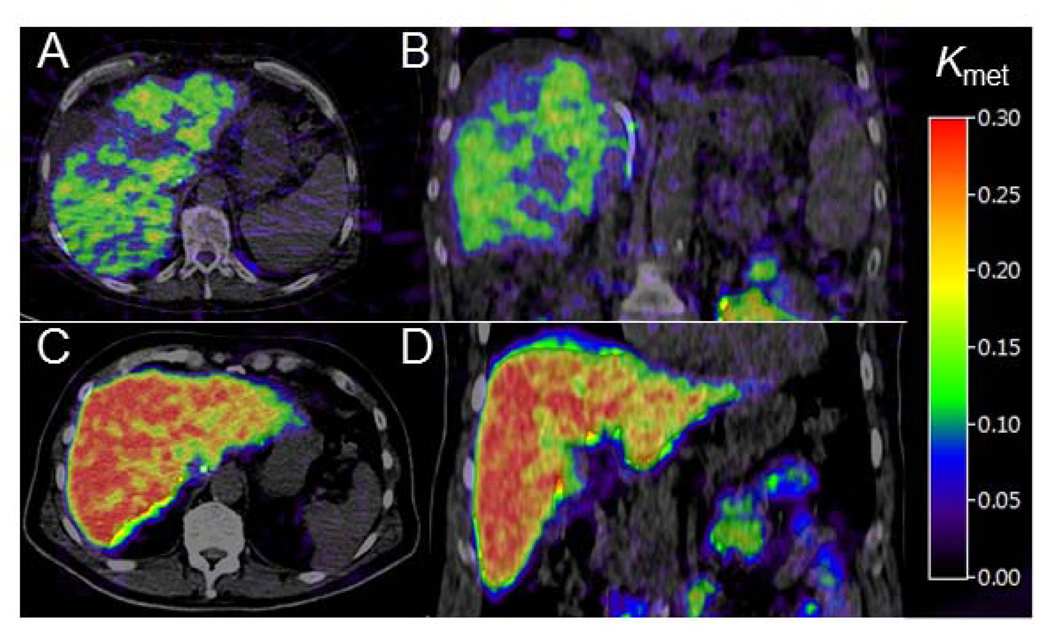

The volume-of-interest based analysis of PET data validated the use of the kinetic model applied to data and formed the basis for generating parametric images of Kmet. Fig. 1 shows examples of parametric images of Kmet in a patient with cirrhosis (Panels A and B) and a healthy subject (Panels C and D). In patients, mean CoV for Kmet in liver tissue was 24.4% (range, 19.7–29.9) which was significantly higher than the mean value of 14.4% (range, 9.2–17.9) (p <0.0001) in healthy subjects (Table 2).

Fig. 1. Examples of parametric images of the hepatic systemic clearance of FDGal (Kmet, ml blood/ml tissue/min) generated from dynamic FDGal PET/CT recordings.

Top row is from a cirrhotic patient (panels A and B) and bottom row is from a healthy subject (panels C and D). Left images are transaxial, right images coronal. The patient is a 57 year old male with cirrhosis (alcohol and hepatitis C virus), a global liver function of 45% of expected value as measured by a galactose elimination capacity (GEC) test, and portal hypertension (HVPG 30.5 mmHg).

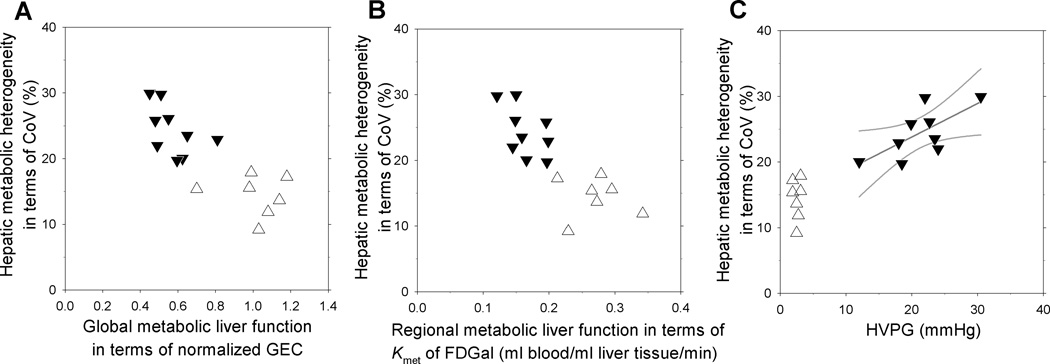

The relationships between metabolic heterogeneity in terms of CoV for Kmet and global metabolic liver function (normalized GEC), regional metabolic liver function (Kmet) and HVPG are plotted in Fig. 2A–C. As seen, there was a trend towards negative correlations between increased metabolic heterogeneity in patients and decreased global and local metabolic liver function, but the correlations did not reach statistically significance (p =0.16 for CoV against normalized GEC; p =0.13 for CoV against Kmet). A positive correlation between the metabolic heterogeneity in the liver parenchyma and HVPG was found in the patients (p <0.05). No significant correlations were found between MELD score and normalized GEC, Kmet for FDGal, metabolic heterogeneity or HVPG (p >0.3 for all).

Fig. 2. Intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity plotted against global and regional metabolic function and HVPG.

The intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity is expressed in terms of the coefficient of variation (CoV) for Kmet (ml blood/ml liver tissue/min) of hepatic FDGal metabolism. Individual values from cirrhotic patients (▼) and healthy subjects (Δ) are plotted against global metabolic liver function (A), regional metabolic liver function (B), and HVPG (C). There was a positive correlation between CoV and HVPG in the patients; the correlation is shown by the straight line with 95% confidence intervals (r =0.69; p <0.05).

Discussion

There is a clinical desire for noninvasive methods that can evaluate regional metabolic function and heterogeneity hereof in a single investigation. In the present study we show that the metabolic function in cirrhotic livers can be measured in terms of galactokinase activity by a relatively short (20 min) dynamic FDGal PET/CT scan. This enables measurements of metabolic liver function both for the whole liver (global function) or any region of interest (regional function) in a single investigation. Compared to biopsies, which are invasive with potentially serious complications and which represent only a very small part of the liver, FDGal PET/CT provides functional information of the whole liver, it is a safe procedure, and it can be repeated several times e.g. to monitor metabolic liver function and the degree of heterogeneity following treatment.

The hypothesis that patients with cirrhosis have an increased intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity when compared to healthy subjects was verified. Based on the fact that liver histology exhibits considerable heterogeneity when affected by parenchymal disease regardless of aetiology [23–26] this finding may not be surprising but the present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to use a validated method to demonstrate this.

Hepatic metabolism of galactose, and thus of FDGal, has several advantages for in vivo measurements of hepatic metabolic function; the galactokinase enzyme is almost exclusively found in the liver, the metabolism follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics and it is not regulated by hormones such as insulin or glucagon [5,27,28]. Due to a high substrate specificity of galactokinase, FDGal has a weaker interaction with the enzyme than galactose which, for the present purpose, is an advantage because the hepatic removal kinetics of FDGal thus is predominantly enzyme-determined. This means that only changes in enzymatic capacity, i.e. metabolic function, and not changes in e.g. hepatic blood flow will be reflected by this measure [29]. Furthermore, the approximation of Ksyst to Vmax/Km was found to be similar to that in healthy subjects [5]. This is important because changes in the PET measure over time then can be ascribed directly to changes in metabolic capacity. Ksyst was used to validate the PET measure Kmet because both measures are systemic clearances, the only difference being that Ksyst is for the whole liver (global) and Kmet provides a regional measure in terms of per ml liver tissue. By demonstrating the presence of significantly increased intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity in cirrhotic livers, we underline the importance of regional evaluation of cirrhotic livers in order to predict remnant liver function following e.g. partial liver resection.

By applying the present method in conjunction with diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT, the mean Kmet for FDGal in any region of the liver can be quantified in relation to the Kmet for the whole liver, i.e. a regional-to-global estimation of metabolic liver function. This estimate can be used to assess remnant metabolic liver function following surgery and it would be interesting to make a direct comparison between metabolic function in terms of Kmet for FDGal and histological appearance in the removed part of the liver. Another important issue that now can be addressed is the comparison between the volume of the part being removed and the relative liver function. This is particularly interesting in patients with heterogeneous livers because a removal of e.g. 25% of the liver may result in a significantly different change in liver function [2]. FDGal PET/CT also enables studies of the regional effects of stereotactic radiation therapy of liver tumours on metabolic function in surrounding liver tissue function [30]. As discussed above, this measure will be unbiased by any changes in blood perfusion in treated areas because it is predominantly enzyme-determined.

While the importance of hemodynamic changes in terms of increased vascular resistance and portal hypertension for the development of clinical complications in liver disease is well known, little is known about the interplay between regional metabolic liver function and HVPG. Recent studies have shown that in established cirrhosis, septal thickness and the amount of fibrosis, viz. changes that each contributes to increased histological heterogeneity, are predictors of the presence of HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg [31,32], suggesting a correlation between the structural changes and clinically significant portal hypertension. An interesting finding in the present study is thus the positive correlation between HVPG and the intrahepatic heterogeneity in metabolic function because it indicates a potential role of functional imaging with FDGal PET/CT in the overall clinical evaluation of patients with cirrhosis. The method presented here may thus become of prognostic significance with regards to the development of clinical complications in patients with liver cirrhosis because it enables, for the first time, a noninvasive evaluation of the metabolic function of the cirrhotic liver which may even be more accurate than more indirect markers such as albumin or bilirubin. All patients in the present material had relatively low MELD scores which correlated with neither normalized GEC nor HVPG. The apparent correlation between HPVG and metabolic heterogeneity thus suggests that functional evaluation of the liver by FDGal PET/CT may improve the evaluation of patients, especially those with low MELD scores, but this needs to be tested in a larger prospective study.

In Denmark, alcohol is the leading aetiological factor for cirrhosis and in the present study, only one patient with hepatitis C virus was included. We are confident, however, that the method will also prove useful for monitoring metabolic liver function in patients treated for HCV or patients with other liver diseases. Also, due to the logistics of the project, only patients with Child-Pugh scores A and B were included in the present study, but the short FDGal PET/CT method without liver vein blood sampling is applicable also to patients in Child-Pugh class C. For ethical reasons, we included patients who were referred for HVPG measurement because calculation of Ksyst required collection of blood from a liver vein. We would like to emphasize that the liver vein catheter is not necessary for determination of Kmet for FDGal from PET/CT data; for future studies, a short (20 min) dynamic PET/CT study with arterial blood sampling is thus sufficient for quantification of hepatic metabolic function in terms of metabolic clearance of FDGal. The inclusion criterion caused the HVPG measurements to be relatively high with the lowest HVPG value being 12 mmHg, meaning that all patients had clinically significant portal hypertension but we are confident that the FDGal PET/CT method is also valuable for patients with lower pressure gradients. Because FDGal is produced by a method similar to the one used for routine production of the widely used glucose tracer 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) [18], the tracer can be produced in most PET facilities and the radioactive half life of FDGal (110 minutes) means that it can be transported to nearby centres, abolishing the need for an onsite cyclotron. Accordingly, the FDGal PET/CT method is likely to become commonly available for evaluation of regional liver function.

In conclusion, we have validated the use of FDGal PET/CT for measuring global and regional metabolic function in the cirrhotic liver in terms of galactokinase capacity by a short (20 min) FDGal PET/CT recording. We also demonstrate a substantial intrahepatic metabolic heterogeneity in cirrhotic livers which correlated positively with HVPG. This could become important in the assessment of the clinical severity of liver disease and thus have direct clinical implications for noninvasive investigation of patients with liver cirrhosis, but this needs to be validated in a larger study.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients who participated in the study and the staff at the PET Center.

Funding

The study was supported in part by the Danish Council for Independent Research (Medical Sciences, 09-067618 and 09-073658), the NIH (R01-DK074419), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, Aase and Ejnar Danielsen’s Foundation, and the A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Pinzani M, Vizzutti F, Arena U, et al. Technology Insight: noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by biochemical scores and elastography. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:95–106. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Graaf W, Bennink RJ, Veteläinen R, van Gulik TM. Nuclear imaging techniques for the assessment of hepatic function in liver surgery and transplantation. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:742–752. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sørensen M, Munk OL, Mortensen FV, Olsen AK, Bender D, Bass L, Keiding S. Hepatic uptake and metabolism of galactose can be quantified in vivo by 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxygalactose positron emission tomography. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G27–G36. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00004.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sørensen M. Determination of hepatic galactose elimination capacity using 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-galactose PET/CT: reproducibility of the method and metabolic heterogeneity in a normal pig liver model. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:98–103. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.510574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sørensen M, Mikkelsen KS, Frisch K, Bass L, Bibby BM, Keiding S. Hepatic galactose metabolism quantified in humans using 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-galactose PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1566–1572. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tygstrup N. Determination of the hepatic elimination capacity (Lm) of galactose by single injection. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1966;18:118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tygstrup N. Effect of sites of blood sampling in determination of the galactose elimination capacity. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1977;37:333–338. doi: 10.3109/00365517709092638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranek L, Andreasen PB, Tygstrup N. Galactose elimination capacity as a prognostic index in patients with fulminant liver failure. Gut. 1976;17:959–964. doi: 10.1136/gut.17.12.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt LE, Ott P, Tygstrup N. Galactose elimination capacity as a prognostic marker in patients with severe acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: 10 years’ experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:418–424. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkel C, Marchesini G, Fabbri A, Bianco S, Bianchi G, Enzo E, et al. The course of galactose elimination capacity in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: possible use as a surrogate marker for death. Hepatology. 1996;24:820–823. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008855183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Ott P, Keiding S, Andersen PK, Tygstrup N. The galactose elimination capacity and mortality in 781 Danish patients with newly-diagnosed liver cirrhosis: a cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;30:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redaelli CA, Dufour JF, Wagner M, Schilling M, Hüsler J, Krähenbühl L, et al. Preoperative galactose elimination capacity predicts complications and survival after hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2002;235:77–85. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sørensen M, Frisch K, Bender D, Keiding S. The potential use of 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-galactose as a PET/CT tracer for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1723–1731. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1831-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugh RNH, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Brit J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen NC. Correction for blank density in spectrophotometric dye determination in turbid plasma within the spectral range 600 to 920 nanometers (a method of universal applicability derived from Gaebler’s law on the basis of simple theoretical considerations. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1963;15:610–612. doi: 10.3109/00365516309051343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen NC. Spectrophotometric determination of indocyanine green in plasma especially with a view to an improved correction for blank density. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1963;15:613–621. doi: 10.3109/00365516309051344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skak C, Keiding S. Methodological problems in the use of indocyanine green to estimate hepatic blood flow and ICG clearance in man. Liver. 1987;7:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1987.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisch K, Bender D, Hansen SB, Keiding S, Sørensen M. Nucleophilic radiosynthesis of 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-galactose from Talose triflate and biodistribution in a porcine model. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler K, Bass L, Henriksen J, Larsen OA, Ring P, Tygstrup N. Heterogeneity of splanchnic vascular transit times in man. Clin Physiol. 1983;3:537–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1983.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler K, Bass L, Keiding S, Tygstrup N. The physiological basis for clearance measurements in hepatology. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1979;14:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gjedde A. Calculation of cerebral glucose phosphorylation from brain uptake of glucose analogs in vivo: a re-examination. Brain Res Rev. 1982;4:237–274. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(82)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:1–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrams GA, Kunde SS, Lazenby AJ, Clements RH. Portal fibrosis and hepatic steatosis in morbidly obese subjects: A spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;40:475–483. doi: 10.1002/hep.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janiec DJ, Jacobson ER, Freeth A, Spaulding L, Blaszyk H. Histologic variation of grade and stage of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in liver biopsies. Obes Surg. 2005;15:497–501. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maharaj B, Maharaj RJ, Leary WP, Cooppan RM, Naran AD, Pirie D, et al. Sampling variability and its influence on the diagnostic yield of percutaneous needle biopsy of the liver. Lancet. 1986;1:523–525. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballard FJ. Purification and properties of galactokinase from pig liver. Biochem J. 1966;98:347–352. doi: 10.1042/bj0980347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keiding S, Johansen S, Winkler K, Tonnesen K, Tygstrup N. Michaelis-Menten kinetics of galactose elimination by the isolated perfused pig liver. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:1302–1313. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.5.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keiding S, Sørensen M. Hepatic removal kinetics: importance for quantitative measurements of liver function. In: Rodés J, Benhamou JP, Blei A, Reichen J, Rizzetto M, editors. Textbook of Hepatology: From Basic Science to Clinical Practice. 3. ed. Volume 1. London: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sørensen M, Høyer M, Keiding S. Regional liver tissue damage induced by stereotactic radiotherapy of liver tumours quantified by [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-galactose PET/CT. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl.2):S395–S396. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagula S, Jain D, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G. Histological-hemodynamic correlation in cirrhosis – a histological classification of the severity of cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2006;44:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sethasine S, Jain D, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao Guadalupe. Quantitative histological-hemodynamic correlations in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;55:1146–1153. doi: 10.1002/hep.24805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]