Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine the efficacy of once-yearly intravenous zoledronic acid (ZOL) 5 mg in reducing risk of clinical vertebral, nonvertebral, and any clinical fractures in elderly osteoporotic postmenopausal women.

DESIGN

A post hoc subgroup analysis of pooled data from the Health Outcome and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid One Yearly (HORIZON) Pivotal Fracture Trial and the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial.

SETTING

Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

PARTICIPANTS

Postmenopausal women (aged ≥75) with documented osteoporosis (T-score ≤ −2.5 at femoral neck or ≥1 prevalent vertebral or hip fracture) or a recent hip fracture.

INTERVENTION

Patients were randomized to receive an intravenous infusion of ZOL 5 mg (n =1,961) or placebo (n =1,926) at baseline and 12 and 24 months.

MEASUREMENTS

Primary endpoints were incidence of clinical vertebral and nonvertebral and any clinical fracture after treatment.

RESULTS

At 3 years, incidence of any clinical, clinical vertebral, and nonvertebral fracture were significantly lower in the ZOL group than in the placebo group (10.8% vs 16.6%, 1.1% vs 3.7%, and 9.9% vs 13.7%, respectively) (hazard ratio (HR) =0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) =0.54–0.78, P<.001; HR =0.34, 95% CI =0.21–0.55, P<.001; and HR =0.73, 95% CI =0.60–0.90, P =.002, respectively). The incidence of hip fracture was lower with ZOL but did not reach statistical significance. The incidence rate of postdose adverse events were higher with ZOL, although the rate of serious adverse events and deaths was comparable between the two groups.

CONCLUSION

Once-yearly intravenous ZOL 5 mg was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of new clinical fractures (vertebral and nonvertebral) in elderly postmenopausal women with osteroporosis.

Keywords: elderly, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, fractures, zoledronic acid

Osteoporosis is common in elderly postmenopausal women and is associated with a high incidence of fractures. The incidence of osteoporotic fractures is reported to increase with age,1 and more than 50% of all fragility fractures in the community arise in women aged 75 and older.2

Vertebral and hip fractures are highly prevalent in older adults2,3 and contribute to significant morbidity and mortality in this age group.4–9 The incidence of vertebral fractures in women increases strongly with age, ranging from 7.8 per 1,000 person-years at age 55 to 65 to 19.6 per 1,000 person-years at age 75 and older.10

Moreover, patients with previous fractures have higher risk of future fractures11,12 as they lose significant bone and muscle mass.13 Hip fracture is a strong risk factor for subsequent nonhip skeletal fractures in the elderly population. It is not only a marker of prevalent osteoporosis but also a precipitant of functional and bone density decline, which further increases fall and fracture risk.14

Several studies have shown a significant relationship between increasing age and decreasing likelihood of receiving effective osteoporosis treatment.14–18 Thus, untreated osteoporosis leads to an increase in hospitalization and medical expenditure.19 This therapeutic challenge is mainly attributed to two issues. First, elderly patients have been underrepresented in osteoporosis clinical trials, and the efficacy and safety of the available drugs for this population remains unclear.20 Second, the complex and frequent administration requirements of oral bisphosphonates makes it more challenging in patients with cognitive or functional impairments and in those who take multiple oral medications. Consequently, the compliance with oral bisphosphonates is low, and therefore, this disease remains undertreated.21–24

A once-yearly intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid (ZOL) 5 mg is a more-attractive therapeutic option in the management of osteoporosis than daily, weekly, or even monthly regimens of oral bisphosphonates.25 Moreover, the use of intravenous ZOL 5 mg in preventing bone loss and reducing the risk of fractures is well established in post-menopausal osteoporosis.25–28 ZOL is the first intravenous therapeutic agent with documented protection against vertebral and nonvertebral fractures, including hip fracture,25–28 but the efficacy and safety of intravenous bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women aged 75 and older is not well established.

Given the high prevalence of osteoporosis, the under-use of antiresorptive treatment, and the paucity of efficacy and safety data regarding bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis in elderly postmenopausal women, a post hoc analysis was conducted to determine the efficacy and safety of once-yearly intravenous ZOL 5 mg in reducing the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in elderly post-menopausal women aged 75 and older with osteoporosis.

METHODS

Study Design

This post hoc analysis presents the results of pooled data from Health Outcome and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid One Yearly (HORIZON) Pivotal Fracture Trial25 and the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial.28 Both studies were multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

The HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial included 7,765 postmenopausal women with documented osteoporosis (i.e., femoral neck BMD T-score ≤−2.5 with or without evidence of existing vertebral fracture or a femoral neck BMD T-score ≤ −1.5 with radiological evidence of at least two mild vertebral fractures or one moderate vertebral fracture). The HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial included 2,127 patients (men and women) within 90 days of surgical repair of low-trauma hip fracture. In both studies, patients were randomized to receive a once-yearly 15-minute intravenous infusion of ZOL 5 mg or placebo (on Day 0 and at 12 and 24 months) and were monitored over a period of 3 years. In the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial, patients were allowed to take concomitant therapy for osteoporosis (raloxifene, calcitonin, tibolone, and hormone replacement therapy) at baseline and during the follow-up. Conversely, in the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial, patients continued to take concomitant medications at the investigator’s discretion. Previous use of other bisphosphonates or parathyroid hormone was allowed with a washout period according to the drug and duration of usage. Previous use of strontium or sodium fluoride was not allowed. In the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial, patients were stratified into Stratum I (patients not taking any osteoporosis medications but taking calcium and vitamin D at the time of randomization) of Stratum II (patients who were taking an allowed medication such as hormone therapy, raloxifene, calcitonin, or tibolone along with calcium and vitamin D at the time of randomization). Patients with hypersensitivity to bisphosphonates, creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min, and corrected serum calcium level greater than 2.8 or less than 2.0 mmol/L were excluded in both trials.

In addition to the study drug, all patients received calcium (1,000–1,500 mg) and vitamin D (400–1,200 IU). Patients in the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial were given a loading dose of vitamin D2 (75,000–125,000 U) or vitamin D3 (50,000–75,000 U) 14 days before infusion of the study drug, depending upon their levels of serum 24-hydroxy vitamin D.

The primary endpoints in the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial were new morphometric vertebral (in Stratum I) and hip (in both strata) fractures. The secondary efficacy endpoints were new clinical, clinical vertebral, and nonvertebral fractures and changes in bone mineral density (BMD) at the total hip, femoral neck, and lumbar spine along with bone turnover markers level. The primary endpoint in the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial was a new clinical fracture (morphometric vertebral fractures were not assessed) excluding facial and digital fractures. The secondary efficacy endpoints were new clinical vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures and changes in total hip and femoral neck BMD. Both HORIZON trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the appropriate local ethics committees and institutional review boards.

Study Population

This primary analysis included all female patients aged 75 and older who were enrolled in both HORIZON trials. Data from patients younger than 75 are also presented to assess whether these patients had a similar incidence of prevalent fractures, beneficial effects on BMD, and incidence of adverse events (AEs) after treatment.

Efficacy Variables

The primary efficacy variables were the cumulative incidence of clinical vertebral and nonvertebral fractures or any clinical fracture over 3 years in patients aged 75 and older. Morphometric vertebral fracture incidence was not assessed in the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial; therefore, the focus of this analysis was on the incidence of clinical fractures, nonvertebral fractures, and clinical vertebral fractures. The secondary efficacy variables were the incidence of hip fractures, changes in BMD at the femoral neck, and total hip BMD at 1 and 3 years.

In the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial, a central reader blinded to the study group assignment compared the community-obtained radiograph for a clinical vertebral fracture with the baseline study radiograph. A central committee assessed and confirmed the radiological or surgical report for nonvertebral fractures and excluded the fractures related to excessive trauma.

In the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial, clinical vertebral fracture was defined as new or worsening back pain with a reduction in vertebral height of 20% (Grade 1) or more from the baseline radiograph or a reduction in the vertebral body height of 25% (Grade 2) or more if no baseline radiograph was available. A nonvertebral fracture, confirmed according to a radiograph or medical document, was defined as a skeletal fracture that was not a vertebral, facial, digital, or skull fracture. The details of the methods of assessment have been described elsewhere.25,28

Total hip BMD was derived from the femoral neck, trochanter, and intertrochanter BMD measurements performed using dual X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic, Bedford, MA, or GE Lunar, Madison, WI, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry machines). All BMD measurements were corrected for any site- and equipment-related differences.29,30 Changes in bone turnover markers (BTMs; serum β-C-telopeptide (β-CTx), bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP), and N-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP) from baseline were assessed in the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial alone.

Safety Variables

All AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) were recorded for safety assessment. This also included physical examination, regular measurement of vital signs, hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis, assessments of renal abnormalities (pre- and postdose administration), postdose symptoms (myalgia, headache, arthralgia, fever), and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities was used for AE coding.

Statistical Analyses

The intention-to-treat population included all randomized patients. The data were summarized for demographic and baseline characteristics. The baseline data of patients younger than 75 and those aged 75 and older in the ZOL treatment arm and the placebo arm were compared using descriptive statistics. Between-treatment differences in clinical vertebral, nonvertebral, hip, and any clinical fracture at 1 and 3 years were analyzed within each age group using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with treatment, stratified according to study to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the cumulative fracture event rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. To evaluate the treatment-by-age interaction, an additional Cox regression model with treatment and age group (<75 and ≥75) stratified according to study was evaluated. Between-treatment differences in the percentage change in total hip and femoral neck BMD from baseline within each age group were evaluated using an analysis of variance model with treatment and study as explanatory variables. An additional model was evaluated to assess the treatment-by–age group interaction including treatment, study, age group (<75 and ≥75) and the treatment-by–age group interaction as explanatory variables. Changes in BTMs within each age group were evaluated using an analysis of covariance (loge ratio of the postbaseline value to the baseline value) model with treatment stratum and center. An additional model was evaluated that also included age group and the treatment-by–age group interaction as explanatory variables. The number and percentage of patients experiencing common AEs and other clinically significant safety events (atrial fibrillation, renal events, deaths, SAEs) was presented according to treatment and age group. Between-treatment differences for each group were evaluated using the Fisher exact test.

RESULTS

There were 9,354 postmenopausal women included in both HORIZON trials: 5,467 younger than 75 and 3,887 aged 75 and older. Baseline characteristics in both groups are given in Table 1. Femoral neck BMD was similar in both age groups (femoral neck T-score ≤ −2.5: 64.4% of those <75, 70.0% of those ≥75).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis Younger than 75 and Aged 75 and Older in Both Treatment Groups

| Characteristic | <75

|

≥75

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n =2,736) | ZOL (n =2,731) | Placebo (n =1,927) | ZOL (n =1,961) | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 69.1 ± 3.7 | 69.2 ± 3.7 | 79.6 ± 3.7 | 79.3 ± 3.7 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.4 ± 4.4 | 25.1 ± 4.4 | 25.2 ± 4.2 | 25.1 ± 4.3 |

|

| ||||

| Femoral neck bone mineral density, g/cm2, mean ± SD | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

|

| ||||

| Femoral neck T score, n (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| ≤−2.5 | 1,715 (62.7) | 1,806 (66.1) | 1,361 (70.6) | 1,362 (69.5) |

|

| ||||

| >−2.5 | 977 (35.7) | 887 (32.5) | 495 (25.7) | 510 (26) |

|

| ||||

| Prevalent vertebral fracture, n (%)* | ||||

|

| ||||

| 0 | 946 (39.3) | 971 (40.8) | 437 (30.1) | 486 (32.5) |

|

| ||||

| 1 | 666 (27.6) | 657 (27.6) | 410 (28.2) | 436 (29.1) |

|

| ||||

| ≥2 | 796 (33.1) | 749 (31.5) | 605 (41.7) | 574 (38.3) |

|

| ||||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||||

| Calculated creatinine clearance, mL/min, mean ± SD | 70.8 ± 19.2 | 70.0 ± 19.0 | 55.8 ± 15.8 | 55.6 ± 15.0 |

|

| ||||

| Calculated creatinine clearance, mL/min, n (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| <30.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

|

| ||||

| 30.0–34.9 | 13 (0.5) | 17 (0.6) | 120 (6.2) | 90 (4.6) |

|

| ||||

| 35.0–39.9 | 38 (1.4) | 42 (1.5) | 156 (8.1) | 175 (8.9) |

|

| ||||

| 40.0–49.9 | 250 (9.1) | 269 (9.8) | 501 (26.0) | 505 (25.8) |

|

| ||||

| 50.0–59.9 | 516 (18.9) | 535 (19.6) | 476 (24.7) | 515 (26.3) |

|

| ||||

| ≥60.0 | 1,919 (70.1) | 1,867 (68.4) | 666 (34.6) | 671 (34.2) |

|

| ||||

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) |

Data from Health Outcome and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic Acid One Yearly Pivotal Fracture Trial only.

ZOL =once-yearly zoledronic acid 5 mg; SD =standard deviation.

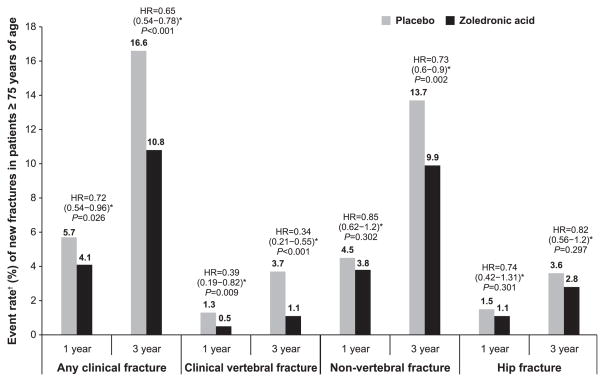

The incidence of any clinical fracture, clinical vertebral, or nonvertebral fracture in postmenopausal women aged 75 and older was significantly lower in the ZOL group than in the placebo group over 3 years (P<.001, P<.001, and P =.002, respectively) (Figure 1). A similar finding has been shown for any clinical fracture and clinical vertebral fractures at 1 year (P =.03 and P =.009, respectively), but the incidence of nonvertebral fracture at 1 year and hip fracture at 1 and 3 years was lower for the ZOL group although not significantly so.

Figure 1.

Event rate of new fractures in patients receiving zoledronic acid (ZOL) 5 mg once yearly and those receiving placebo at 1 and 3 years. *Hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval) of ZOL versus placebo computed from the Cox proportional hazards regression model stratified according to study with treatment as a factor within the subgroup. †Event rate calculated from Kaplan-Meier estimates.

The benefit observed in relative risk reduction of clinical fractures, clinical vertebral fractures, and nonvertebral fractures was comparable in patients younger than 75 and aged 75 and older 1 and 3 years after treatment, and the treatment-by–age group interactions were not statistically significant. However, patients younger than 75 showed a significant benefit in hip fracture risk reduction at 3 years (P<.001) that was not observed in those aged 75 and older, and this treatment-by–age group interaction was statistically significant between the two age groups (P =.04) because of the greater reduction in hip fracture incidence in patients younger than 75. In patients aged 75 and older, femoral neck and total hip BMD was significantly greater in those treated with ZOL than in patients receiving placebo (all P<.001). This was comparable in the ZOL-treated patients younger than 75, and the treatment-by–age group interactions were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage Change in Bone Mineral Density (BMD) in Women Aged 75 and Older with Documented Osteoporosis

| BMD Test Location | Relative Treatment Difference* (95% Confidence Interval) | P-Value† |

|---|---|---|

| Femoral neck BMD | ||

| 1 year | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | <.001 |

| 3 years | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | <.001 |

| Total hip BMD | ||

| 1 year | 3.0 (2.7–3.3) | <.001 |

| 3 years | 6.3 (5.9–6.8) | <.001 |

Least square mean difference of zoledronic acid versus placebo on the percentage change from baseline.

P-value calculated from analysis of variance model with treatment, study.

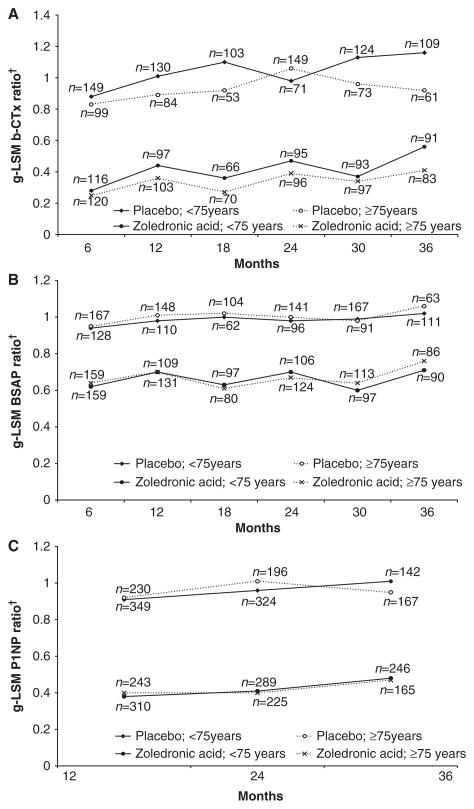

BTMs (serum β-CTX, BSAP, and P1NP) were measured in the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial only and were significantly lower in ZOL- than placebo-treated patients in both age groups (all P<.001); the absolute levels were similar across the age groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Between-treatment bone turnover markers according to visit, age, and treatment group. (A) Serum β-C-telopeptide (b-CTX). (B) Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP). (C) N-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP); n =number of patients with baseline and postbaseline measurement; least square mean (g-LSM) of ratio =exponential of the LSM on the log(e) (ratio =visit/baseline) scale.

The incidence of AEs within 3 days of study drug infusion was higher with ZOL than in the placebo group in both age groups during the 3-year study period (Table 3). In addition, postdose symptoms occurring within 3 days of the study drug infusion were significantly higher with ZOL in patients aged 75 and older (41.5% vs 25.7%, P<.001) and in patients younger than 75 (51.8% vs 24.9%, P<.001). Incidence rates of renal events, including increase in serum creatinine and creatinine clearance; deaths; and SAEs were similar in the two treatment arms for both age groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse Events (AEs) in the Safety Population

| AE | <75

|

≥75

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 2,727) | ZOL (n = 2,721) | P-Value‡ | Placebo (n = 1,921) | ZOL (n = 1,951) | P-Value‡ | |

| Patients with at least one AE | 2,496 (91.5) | 2,548 (93.6) | .003 | 1,763 (91.8) | 1,807 (92.6) | .34 |

|

| ||||||

| AEs within 3 days of study drug infusion | 680 (24.9) | 1,410 (51.8) | <.001 | 494 (25.7) | 809 (41.5) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Death | 58 (2.1) | 62 (2.3) | .71 | 144 (7.5) | 137 (7.0) | .58 |

|

| ||||||

| Serious adverse event | 748 (27.4) | 696 (25.6) | .12 | 728 (37.9) | 732 (37.5) | .82 |

|

| ||||||

| Back pain | 644 (23.6) | 607 (22.3) | .26 | 412 (21.4) | 421 (21.6) | .94 |

|

| ||||||

| Arthralgia | 554 (20.3) | 675 (24.8) | <.001 | 378 (19.7) | 397 (20.3) | .63 |

|

| ||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 274 (10.0) | 267 (9.8) | .79 | 261 (13.6) | 293 (15.0) | .21 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 286 (10.5) | 301 (11.1) | .51 | 238 (12.4) | 250 (12.8) | .70 |

|

| ||||||

| Pyrexia | 124 (4.6) | 523 (19.2) | <.001 | 76 (4.0) | 236 (12.1) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Pain in extremity | 246 (9.0) | 291 (10.7) | .04 | 178 (9.3) | 190 (9.7) | .62 |

|

| ||||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 287 (10.5) | 299 (11.0) | .60 | 168 (8.7) | 171 (8.8) | >.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Myalgia | 104 (3.8) | 324 (11.9) | <.001 | 60 (3.1) | 168 (8.6) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Constipation | 170 (6.2) | 167 (6.1) | .91 | 174 (9.1) | 161 (8.2) | .46 |

|

| ||||||

| Osteoarthritis | 253 (9.3) | 248 (9.1) | .81 | 161 (8.4) | 155 (7.9) | .64 |

|

| ||||||

| Headache | 215 (7.9) | 365 (13.4) | <.001 | 118 (6.1) | 150 (7.7) | .07 |

|

| ||||||

| Nausea | 129 (4.7) | 218 (8.0) | <.001 | 113 (5.9) | 146 (7.5) | .05 |

|

| ||||||

| Dizziness | 151 (5.5) | 174 (6.4) | .19 | 137 (7.1) | 140 (7.2) | >.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Influenza | 240 (8.8) | 241 (8.9) | .96 | 111 (5.8) | 136 (7.0) | .13 |

|

| ||||||

| Cataract | 134 (4.9) | 141 (5.2) | .66 | 109 (5.7) | 132 (6.8) | .16 |

|

| ||||||

| Diarrhea | 144 (5.3) | 143 (5.3) | >.99 | 107 (5.6) | 133 (6.8) | .11 |

|

| ||||||

| Peripheral edema | 88 (3.2) | 100 (3.7) | .37 | 115 (6.0) | 124 (6.4) | .64 |

|

| ||||||

| Anemia | 82 (3.0) | 92 (3.4) | .44 | 96 (5.0) | 123 (6.3) | .08 |

|

| ||||||

| Depression | 117 (4.3) | 132 (4.9) | .33 | 98 (5.1) | 107 (5.5) | .62 |

|

| ||||||

| Bronchitis | 150 (5.5) | 133 (4.9) | .33 | 113 (5.9) | 105 (5.4) | .53 |

|

| ||||||

| Shoulder pain | 122 (4.5) | 163 (6.0) | .01 | 92 (4.8) | 104 (5.3) | .46 |

|

| ||||||

| Fatigue | 83 (3.0) | 126 (4.6) | .002 | 63 (3.3) | 101 (5.2) | .004 |

|

| ||||||

| Influenza-like illness | 65 (2.4) | 246 (9.0) | <.001 | 41 (2.1) | 101 (5.2) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Pneumonia | 82 (3.0) | 75 (2.8) | .63 | 99 (5.2) | 102 (5.2) | >.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Cough | 124 (4.5) | 101 (3.7) | .13 | 95 (4.9) | 99 (5.1) | .88 |

|

| ||||||

| Bone pain | 68 (2.5) | 164 (6.0) | <.001 | 29 (1.5) | 84 (4.3) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Chills | 29 (1.1) | 150 (5.5) | <.001 | 11 (0.6) | 69 (3.5) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Fall | 100 (5.2) | 92 (4.7) | .61 | 83 (3.0) | 70 (2.6) | .25 |

|

| ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation* | 35 (1.3) | 51 (1.9) | .08 | 62 (3.3) | 68 (3.5) | .72 |

|

| ||||||

| Increase in serum creatinine >0.5 mg/dL*,† | 48 (1.8) | 58 (2.2) | .33 | 63 (3.5) | 85 (4.7) | .08 |

|

| ||||||

| Creatinine clearance <30 mL/min*,† | 40 (1.5) | 44 (1.7) | .66 | 163 (9.6) | 180 (10.4) | .43 |

Incidence <5% in any group.

Denominator includes only subjects who had baseline and postbaseline measurements and for creatinine clearance only subject who had a baseline value ≥30 mL/min.

P-value computed from Fisher exact test comparison for each age group.

ZOL =once-yearly zoledronic acid 5 mg.

DISCUSSION

In the post hoc analysis presented, once-yearly intravenous ZOL 5 mg treatment over 3 years significantly reduced the risk of any clinical, clinical vertebral, and nonvertebral fracture in elderly postmenopausal women aged 75 and older with documented osteoporosis or a recent hip fracture. These findings provide evidence of the efficacy of this dosing regimen in patients aged 75 and older reported in this analysis. Moreover, the current analysis showed that the efficacy was comparable in both age groups (≥75 and <75).

The data in patients aged 75 and older were consistent with findings from a previous study with oral bisphosphonates, which reported a reduction in the incidence of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures.31–33 A study evaluating the effect of age on the antifracture efficacy of alendronate revealed no effect of age on the significant relative risk reductions of clinical fractures with alendronate compared with placebo, although the absolute risk reductions for vertebral and hip fractures in women aged 75 and older with low BMD increased with age,34,35 implying a possible improvement in the cost-effectiveness of bisphosphonate treatment in elderly patients.

Patients aged 75 and older showed a reduction in incidence of all but hip fractures, whereas those younger than 75 showed a reduction in incidence of all fracture types. This may be due to the increasing influence of nonskeletal risk factors for these types of fractures, such as falling with older age. Moreover, this was a post hoc analysis, and therefore the sample size used for the analysis was not statistically powered to detect risk reduction for hip fracture within the specified subgroup (≥75). Therefore, in the current analysis of the effect of zoledronic acid according to age, the focus was specifically on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures and not on hip fracture. This remains a limitation of the study, because this was a post hoc analysis that involved two different patient populations.

Overall, the robust effect of ZOL treatment on clinical vertebral fractures in patients aged 75 and older in this analysis supports the concept that ZOL treatment effectively addresses the “skeletal fragility” component of fracture risk, even in relatively older patients with osteoporosis. In the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial, patients with a BMD T-score of −2.5 or less at the femoral neck, with or without evidence of existing vertebral fracture, or a T-score of − 1.5 or less, with radiological evidence of vertebral fracture, were included. In the HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial, patients with a recent hip fracture were included. Thus, whether elderly women with low BMD ( − 2.49 to − 1.5) and no prevalent vertebral fractures would have a significant reduction in fracture incidence from treatment remains unknown.

Treatment with ZOL 5 mg showed a favorable safety profile in elderly patients. The overall incidence rates of AEs, SAEs, and deaths were comparable in ZOL and placebo across both age groups. The incidence of postdose symptoms within 3 days of study drug infusion, such as pyrexia, myalgia, and influenza-like illness, were higher with ZOL 5 mg, as reported previously.25,28 In contrast to the findings reported in the HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial,25,28 the incidence rate of atrial fibrillation events was similar between groups in this analysis.

Adherence to osteoporosis medications is an important problem in the treatment and care of elderly patients.36–38 Approximately 20% to 50% patients abandon their treatment within 6 to 12 months after initiating therapy.37 Non-adherence has been shown to compromise the treatment efficacy on fracture risk reduction and thus significantly increase related medical costs.19,24 The reasons associated with nonadherence in older adults include side effects, therapy administration frequency, and specific administration requirements. The once-yearly intravenous ZOL 5 mg provides an alternative treatment option, which would increase adherence, especially in older adults, by avoiding repeated and complicated dosing regimens.

CONCLUSIONS

Further to the benefits achieved with once-yearly intravenous infusion of ZOL 5 mg in both HORIZON landmark trials, the current ad hoc pooled analysis showed that this treatment was safe and effective in elderly postmenopausal women with osteoporosis aged 75 and older. Moreover, by ensuring full effect for at least 12 months, this therapy may greatly improve osteoporosis treatment in geriatric practice.

Acknowledgments

The study was financially supported by an unrestricted grant from Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Dr. Boonen is senior clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders, Belgium (F.W.O.-Vlaanderen) and holder of the Leuven University Chair in Metabolic Bone Diseases. The authors are thankful to Dr. Pierre Delmas (deceased) for his valuable contribution as a senior clinical investigator. We also thank medical writer Dr. Payal Bhardwaj (MSCD India, Novartis) for her assistance in writing the manuscript and incorporating subsequent revisions.

Funding provided by Novartis Pharma.

Sponsor’s Role: Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland, provided funds for this study.

Footnotes

Submitted to or presented at American Geriatrics Society, April 29 to May 2, 2009, Chicago, IL; International Bone and Mineral Society, March 21 to March 25, 2009, Sydney, Australia; European Congress on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, March 18 to March 21, 2009, Athens, Greece; and International Osteoporosis Foundation, December 3 to December 7, 2008, Bangkok, Thailand.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed significantly to the analysis, interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript and take responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: Novartis Pharmaceuticals funded both HORIZON trials (HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial and HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial). Dr. Dennis M. Black received grant support and honoraria from Novartis and Merck. Dr. Cathleen Colón-Emeric, Dr. Kenneth W. Lyles, Dr. Jay Magaziner, and Dr. Steven Boonen received research funding and are consultants for Novartis. Dr. Peter Mesenbrink is a Novartis employee and shareholder in the company. Dr. Erik Fink Eriksen received grant support from Novartis. Dr. Lyles holds a use patent for zoledronic acid after hip fracture. Dr. Colón-Emeric is supported by Paul A. Beeson award K23 AG024787. Dr. Boonen is senior clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research—Flanders, Belgium (F.W.O.-Vlaanderen) and holder of the Leuven University Chair in Metabolic Bone Diseases. Dr. Richard Eastell received consulting or advisory board fees from Amgen, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, Servier, Ono, and GlaxoSmithKline; lecture fees from Eli Lilly; and grant support from the Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research (UK Department of Health), AstraZeneca, Procter & Gamble, and Novartis.

References

- 1.Melton LJ, III, Thamer M, Ray NF, et al. Fractures attributable to osteoporosis: Report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:16–23. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton LJ, III, Lane AW, Cooper C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of vertebral deformities. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3:113–119. doi: 10.1007/BF01623271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevalley T, Guilley E, Herrmann FR, et al. Incidence of hip fracture over a 10-year period (1991–2000): Reversal of a secular trend. Bone. 2007;40:1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autier P, Haentjens P, Bentin J, et al. Costs induced by hip fractures: A prospective controlled study in Belgium. Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s001980070102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, et al. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:556–561. doi: 10.1007/s001980070075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, et al. Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: A prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1215–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.11.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture-effect of pre-morbid conditions and post-fracture complications. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1583–1593. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magaziner J, Lydick E, Hawkes W, et al. Excess mortality attributable to hip fracture in white women aged 70 years and older. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1630–1636. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ, et al. Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: Risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285:2736–2742. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Klift M, De Laet CE, McCloskey EV, et al. The incidence of vertebral fractures in men and women: The Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1051–1056. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, et al. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: A summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–739. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Hannan MT, et al. Second hip fracture in older men and women: The Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1971–1976. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox KM, Magaziner J, Hawkes WG, et al. Loss of bone density and lean body mass after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s001980050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colon-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, Pieper C, et al. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: Data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:879–883. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gehlbach SH, Bigelow C, Heimisdottir M, et al. Recognition of vertebral fracture in a clinical setting. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:577–582. doi: 10.1007/s001980070078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simonelli C, Killeen K, Mehle S, et al. Barriers to osteoporosis identification and treatment among primary care physicians and orthopedic surgeons. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:334–338. doi: 10.4065/77.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Demetrakopoulos D, et al. Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2005;87:3–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade SE, Majumdar SR, Chan KA, et al. Low frequency of treatment of osteoporosis among postmenopausal women following a fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2052–2057. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ. Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone. 2006;38:922–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Katz JN, et al. Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Am J Med. 2003;115:398–400. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M, et al. Determinants of non-compliance with bisphosphonates in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1337–1344. doi: 10.1185/030079908x297358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, et al. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–1460. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, et al. Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:922–928. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: Relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1013–1022. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid IR, Brown JP, Burckhardt P, et al. Intravenous zoledronic acid in post-menopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:653–661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black DM, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, et al. Defining incident vertebral deformity: A prospective comparison of several approaches. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:90–101. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Fuerst T, Hui S, et al. Standardization of bone mineral density at femoral neck, trochanter and Ward’s triangle. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:438–444. doi: 10.1007/s001980170087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: A randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochberg MC, Thompson DE, Black DM, et al. Effect of alendronate on the age-specific incidence of symptomatic osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:971–976. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boonen S, McClung MR, Eastell R, et al. Safety and efficacy of risedronate in reducing fracture risk in osteoporotic women aged 80 and older: Implications for the use of antiresorptive agents in the old and oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1832–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, et al. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:1003–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Dolovich L, et al. Patient adherence to osteoporosis medications: Problems, consequences and management strategies. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:37–55. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Eijken M, Tsang S, Wensing M, et al. Interventions to improve medication compliance in older patients living in the community: Asystematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:229–240. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]