Abstract

Dry eye disease (DED) is a growing public health concern causing ocular discomfort, fatigue and visual disturbance that interferes with quality of life (QoL), including aspects of physical, social, psychological functioning, daily activities and workplace productivity. This paper assesses the current understanding of the impact of DED on QoL and vision. The full impact of DED on a patient’s QoL is not easily quantifiable, but several methods and techniques have been evaluated to measure the decreased quality of vision from DED, and a number of questionnaires have been developed to quantify the impact of DED on various aspects of patient QoL. We summarize available evidence on the impact of DED based on a review of published literature.

Keywords: Dry eye disease, Quality of life, Quality of vision, Functional visual aquity, Questionnaire

Introduction

According to the International Dry Eye Work Shop in 2007, “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface” 1. Dry eye disease (DED) is one of the most prevalent ocular surface diseases in the world. The prevalence of DED has been reported to occur in the range of approximately 4.4% to as high as 50%2-9 among middle-aged and older people throughout the world. In the US, estimates from the largest studies suggest that DED affects around 5 million people ≥50 years of age8. Symptoms of DED are a common motivation for patients to seek eye care, and have emerged as crucial outcome measures for clinicians as well as in studies assessing the impact of DED treatments. Accordingly, measurement of the impact of DED on patients’ daily lives is now recognized as a critical aspect of disease characterization.

Researchers in the field have worked to develop increasingly robust ways of measuring patient-reported outcomes in DED. With the improvement and expansion of available techniques to evaluate the impact of DED on people’s lives, there is a growing body of evidence detailing the depth and breadth of the impact of DED on QoL and vision. A major impact of DED, as included in its definition, is its effect on visual function. People with DED often report visual disturbances such as blurred or foggy vision, fluctuating vision, and glare; often in spite of normal visual acuity using standard testing techniques. The resulting reductions in visual function can be measured by questionnaires10-12, contrast sensitivity tests13, 14, functional visual acuity (FVA) tests15-21, and measurement of higher-order optical aberrations (HOA)22-25. DED also impacts other aspects in the everyday quality of life (QoL) of patients, including physical, social, psychological, and workplace productivity. The physical impact of DED seems most closely related to the concept of DED as a type of chronic pain syndrome, which results in chronic symptoms of ocular surface discomfort with subsequent effects on a number of aspects of QoL.

QoL as assessed by questionnaires developed specifically for DED

In recent years, a number of patient-reported outcomes questionnaires have been developed to assess patients’ experience in DED10, 12, 26. These questionnaires include those directed at measuring ocular surface comfort symptoms (e.g. the Symptom Assessment iN Dry Eye [SANDE] questionnaire based on a visual analogue scale approach, and the Ocular Comfort Index [OCI] questionnaire developed using the technique of Rasch analysis); as well as questionnaires aimed at measuring both ocular surface comfort symptoms as well as the impact of DED on other aspects of a patient’s QoL. We describe a few such questionnaires below.

For example, the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI),10 consists of 12 questions and has been frequently used to measure the severity of dry eye disease, including in the setting of clinical trials. The OSDI contains three subscales: ocular discomfort symptoms (OSDI-symptoms), vision-related function (OSDI-function), and environmental triggers (OSDI-triggers), which are all queried by 3 or more questions which direct the patient to their experience over the past week. More specifically, the OSDI includes 3 items related to ocular discomfort (feeling sensitive to light, gritty, and painful or sore eyes); and 6 questions related to visual disturbance (blurred vision, or poor vision) or visual function (problems reading, driving at night, working on a computer, or watching TV); and 3 questions related to possible symptom triggers (windy conditions, low humidity, or areas that are air-conditioned).

The OSDI was shown to validly distinguish among patients with no DED and mild, moderate, and severe DED10. It has since been used in a number of research papers and randomized trials27,28, 29 and data from the OSDI demonstrate the higher level of ocular surface symptoms in patients with DED. For example, A comparative study including 87 patients with DED showed that the dry eye patient group had higher (worse) OSDI composite and subscale scores of ocular symptoms, vision-related function, and environmental triggers (all P < 0.001), compared to a group of 71 patients without DED27. Another study with 40 participants with clinical evidence of DED showed that the OSDI total score was significantly greater in patients suffering with DED as compared to normal subjects30.

The Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ)26 includes 21 items developed to evaluate the prevalence, frequency, diurnal severity and intrusiveness of dry eye symptoms for use in epidemiologic and clinical studies. The questions inquire about the frequency of ocular discomfort, dryness, visual changes, soreness and irritation, grittiness and scratchiness, burning and stinging, foreign body sensation, light sensitivity, and itching. It also includes questions on age, gender, daily activities, computer use, use of systemic and ocular medications, allergies, self-assessment, and previous diagnosis of dry eye. There are 4 questions in the DEQ related to visual disturbance, such as frequency of visual changes, how noticeable the changes are during the morning or before bed, as well as how much the visual fluctuation bother the patients. A study with 100 patients using the DEQ found symptoms of ocular irritation were frequent and intense among patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and keratoconjunctivitis sicca compared with controls. These symptoms often increased in intensity over the day, suggesting that open-eye conditions affect the progression of symptoms26.

Another questionnaire used for epidemiologic and clinical studies, the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL)12 ,consists of 57 questions comprising 3 modules: dry eye symptom bother; impact on daily life including daily activities, emotional impact, impact on work; and treatment satisfaction (both effectiveness and treatment-related bother/inconvenience). The items related to visual disturbance are 2 items on how much the person is bothered by “blurry vision” or “sensitivity to light, glare, and/or wind”. Authors have observed statistically significant differences in responses to the IDEEL questionnaire across varying levels of DED severity12. One study with 74 subjects found IDEEL-symptom bother (SB) significantly discriminated dry eye severity, and after the treatment of dry eye disease the IDEEL -SB dropped among improved subjects31.

In the clinical setting, in addition to symptoms of ocular surface pain and discomfort, doctors often encounter patient complaints of blurred vision even though the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity is normal when measured with a Snellen or other standard visual acuity chart. Consistent with this, studies of patients with DED using patient reported outcome instruments have consistently identified problems with performance of daily activities that require sustained visual attention. For example, a study using the DEQ found that 10% of patients with non-Sjogren syndrome DED and 30% of patients with Sjogren syndrome DED32 complained about impaired vision. Others have reported that between 42% and 80% of patients with primary Sjogren syndrome experienced ”disturbed vision”33,34. In addition, a study from Japan showed that blurred vision was reported in 22% of DED patients35.

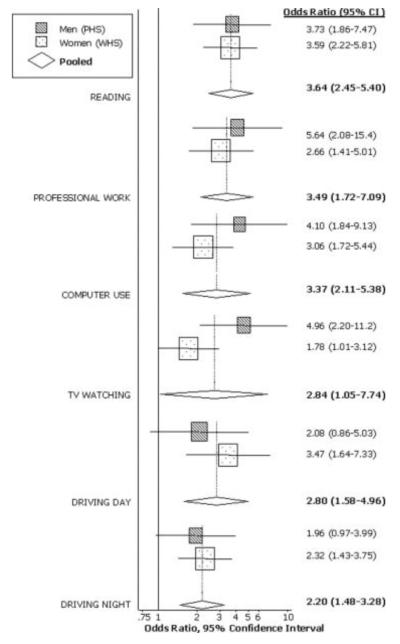

In one of the first studies of its kind, data from a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Study (WHS)8 and Physicians’ Health Study (PHS)36 demonstrated that people with DED are significantly more likely than people without DED to report problems with reading (odds ratio [OR] 3.64, 95% confidence confidence interval [CI] 2.45-5.40), performing professional work (OR 3.49, 95% CI 1.72-7.09), computer use (OR 3.37, 95% CI 2.11-5.38), television watching (OR 2.84, 95% CI 1.05-7.74), daytime driving (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.58-4.96), and nighttime driving (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.48-3.28)37 (Figure 1). A later study from Singapore with 3239 individuals aged ≥40 years showed that patients with symptomatic dry eye reported significantly more difficulty in performing vision-related daily activities, independent of their visual acuity. The specific activities that were affected by symptomatic dry eye were navigating stairs, reading road signs, reading newspaper, cooking, recognizing friends, watching television, and driving at night38.

Figure 1. Permission from AJO.

Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, et al. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143 :409-15.

Use of utility assessments in DED

Utility assessment is a formal method for quantifying and understanding the relative impact of a given health state or disease on patients. One of the advantages of this technique is that utility scores that are anchored at perfect health (utility=1) and death (utility=0) can be compared across various health outcomes using a time trade-off (TTO) method39. Two studies used the technique of utility assessment to estimate the QoL impact of DED, finding that for patients with severe DED, the impact of their disease on their lives was similar to the impact of moderate to severe angina40, 41. Schiffman found that for the most severe DED cases (requiring tarsorrhaphy), the impact was worse than that reported for disabling hip fracture41. Buchholz P et al. from the United Kingdom showed a similar result; forty-four patients with moderate to severe dry eye were surveyed via interactive utility assessment software. Utility values were measured by TTO and Standard Gamble (SG) methods. Using TTO, the mean score for asymptomatic dry eye (0.68) was similar to that for “some physical and role limitations with occasional pain” and severe DED requiring surgery scored 0.56, similar to hospital dialysis (0.56-0.59) and severe angina (0.5). Utilities described for scenarios of dry eye severity levels were slightly higher (less severe impact) for patients self-reported as mild-to-moderate versus those self-reported as severe40.

Use of generic health or generic eye health questionnaires in DED

The Short Form-36 (SF-36)42 questionnaire is a widely accepted generic metric for assessment of health-related QoL that has been applied in the setting of DED. The SF-36 is a multi-purpose, short-form health survey with 36 questions. It yields an 8-scale profile of functional health including physical functioning, role limitation because of physical disability, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional limitation because of emotional disability, and mental health. These measures are summarized by a physical component summary score and mental component summary score. Patient responses to the SF-36 showed that DED has a measureable negative impact on such general health assessments. Indeed, in one study, even patients with mild DED had consistently lower role-physical and bodily pain scores compared to normal patients, whereas patients with moderately severe disease experienced not only these losses but also measureable reductions in reported vitality and poorer general health. The group with severe DED scored lower than the normal across all SF-36 domains except role-emotional and mental health43. A link of DED with emotional and mental health has also been demonstrated with other methodologies, for example, an association between the use of antidepressant medication and risk of DED was observed in the PHS36, and this finding is also consistent with data from at least two other epidemiological studies44, 45.

Generic visual function questionnaires such as the National Eye Institute’s Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI VFQ-25) have also been used in many studies of DED27, 46-48. The NEI VFQ-25 is a 25-item questionnaire has five nonvisual domains: general health, mental health, dependency, social function, role limitations; and seven visual domains: general vision, distance vision, peripheral vision, driving, near vision, color vision, and ocular pain. It has been shown to be a useful tool for group-level comparisons of vision-targeted, health-related QOL in clinical research for multiple eye conditions. Of specific interest for DED, the questionnaire contains items on vision-related QoL as well as 2 ocular pain subscale questions. Nichols et al. used the NEI VFQ-25, to study vision-related quality of life among predominantly mild to moderate DED patients, particularly in relation to reported ocular pain48. In these patients, the pain and discomfort subscale of this instrument had the lowest score of all the subscales (83.8%). Further, a population-based cross-sectional study from China with 229 patients shows that NEI VFQ-25 scores were significantly lower in subjects with DED (P = 0.003). Moreover, this study found the subscale scores of ocular pain and mental health were significantly lower in those with either DED or dry eye symptoms only (both P<0.001)47. Another study showed that DED group had worse NEI VFQ-25 scores for the subscales of general health, general vision, ocular pain, short distance vision activities, long distance vision activities, vision related social function, vision related mental health, vision related role difficulties, vision related dependency, and driving27. The NEI VFQ-25 subscales scores were generally low, with significantly lower scores for general health, general vision, and ocular pain27. The low NEI VFQ-25 scores reported by patients with DED in that study correspond well to those reported by Nichols and associates and Vitale and associates48, 49.

It also deserves mention that patients with topically treated glaucoma present with DED more often than a similar control group, and the presence of DED negatively influences QoL in this group of patients over and above the presence of glaucoma itself50.

The prevalence and the risk of DED appears to be higher in glaucoma patients51, and an observational cross-sectional study with 61 patients who were treated with glaucoma medications showed that QoL measured by the NEI VFQ-25 was significantly reduced among glaucoma patients who also developed DED50.

Contrast sensitivity measurement

Contrast sensitivity tests measure the ability of the eye to discern between aspects of different brightness in an image; patients with poor contrast sensitivity may have difficulty identifying details in patterns or distinguishing facial features. In fact, the visibility of object is often limited more by its contrast than by its size, which can be demonstrated on certain contrast sensitivity charts. In so far as contrast sensitivity tests measure the ability to distinguish objects from their background, they provide additional information about the visual system than can be obtained by visual acuity measurement alone. With the use of Vistech chart which presents sine wave gratings at set contrast levels, Roland et al found a significant decrease in contrast sensitivity in DED patients with punctuate epithelial keratopathy (PEK) compared to patients without52. Using a chart-based system that presented sine wave gratings of fixed contrast, Huang et al reported that contrast sensitivity in DED patients decreased regardless of the presence of PEK13. Ridder et al employed computer-generated sine-wave gratings that were briefly presented (16 ms duration), and demonstrated that DED patients exhibit a decrease in contrast sensitivity when the tear film breaks up53. These measureable changes in contrast sensitivity are indicative of some level of visual impairment in patients with DED, which is consistent with findings using alternative methodologies.

Functional visual acuity (FVA) measurement

FVA tests measure visual acuity during and after sustained visual activity. In this way, the tests are thought to be more representative of visual function in real-life situations such as driving, reading, and using a computer which require prolonged gazing16, 17. A purported advantage of FVA assessments is that they correlate with measures of optical surface irregularities, TFBUT, corneal opacity, and corneal vascularization17, 18. FVA tests appear to have some value in the assessment of visual impairment in patients with DED16.

One FVA measure was first introduced in 2002, and showed a significant decrease in patients with non-Sjogren syndrome and Sjogren syndrome associated DED, despite no change in normal subjects17. The modification of the original FVA methods to enable measurement from a greater distance and accommodate patients with lower baseline visual acuity scores, demonstrated that patients with DED had significantly lower FVA compared with normal controls and the rate of decrease in FVA over time was faster in DED patients19, 20. In one such study, the reported average FVA of DED patients was 20/7117 which is just less than the acuity generally required for licensure for daytime driving in most US states (20/70), and worse than the widely accepted VA cut point of 20/40 for unrestricted driving.

A study comparing patients with DED to normal subjects showed that FVA in DED was significantly lower than control subjects at all time points (10, 20, 30 seconds). This study also showed that FVA significantly improved after punctum plugs insertion in DED patients at all time points19. A further study showed that not only the diagnosis of dry eye, but also the existence of superficial punctuate keretopathy (SPK) resulted in deterioration of the visual function as measured by FVA21 The paper showed a significant correlation between the severity of epithelial damage at the center of the cornea and variation of visual function, as well as coma-like and total higher order aberrations21.

Measurement of Higher-Order Optical Aberrations

There are two general classes of optical aberration: lower-order aberration, which result from refractive errors and higher-order aberrations (HOA). A HOA is a distortion acquired by a wave front of light when it passes through an eye with irregularities of its refractive components such as the tear film, cornea, aqueous humor, crystalline lens and vitreous humor. Optical aberration can be measured by both objective and subjective methods. Wavefront aberrometers assess real-time changes in the optics of the whole eye by measuring refractive anomalies at multiple locations using wavefront technology. Montes showed that, compared with normal controls, DED patients have greater optical aberrations due to increased tear film irregularity, which leads to an uneven corneal surface22. Lin found in post LASIK eyes that DED patients have more rapid disruption of the tear film23. Koh et al. investigated that the sequential post-blink changes in the HOAs had a reverse sawtooth pattern when there was an excessive tear volume in a patient with dry eye who complained of paradoxical visual impairment with epiphora despite an improvement of the dry eye after punctal plug insertion24. Denoyer et al. proved that third-order aberrations in particular, significantly increased over the 10-second period in DED patients, whereas no change occurred in controls. Analysis of the modulation transfer function (MTF) revealed a progressive degradation of ocular optical quality resulting from loss of contrast sensitivity at intermediate and high spatial frequencies in DED patients25.

The economic impact of DED

The burden of DED on the patient and society also includes a substantial economic burden, which can be divided into two categories: direct costs such as medical fees; and indirect costs such as low employment, absence from work, and impaired productivity. Assessment of the economic burden of DED in the US based on survey data collected from 2171 respondents with DED showed that the average annual direct cost of managing a patient with DED is $783 (variation, $757–$809), resulting in an overall annual burden of direct costs for DED for the US healthcare system of $3.84 billion54 Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of dry eye treatment is quite challenging due to the multifactorial nature of the disease and potential limitations of techniques available to evaluate therapeutic outcomes of multi-palliative treatment modalities used. Treatment costs would be predicted to be affected by the availability of various treatments, the quality of the health care system, and the propensity of patients to seek and receive treatment, among other factors. Such predicted differences may be borne out in data such as those from a study that involved 6 European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom) showed that total annual healthcare cost of managing 1,000 DED sufferers managed by ophthalmologists ranged from US$0.27million in France to $1.10million in UK55. These included the cost of specialist visits, diagnostic tests, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. In Asia, Yamada et al. found in a multi-center study evaluating 118 dry eye patients that the annual drug cost was $323 ± 219 US dollars, the clinical cost was 165 ± 101 US dollars, and the total direct costs including punctal plug treatment amounted to $530 ± 384 US dollars56. Investigators from the Singapore National Eye Centre evaluated the cost data from 54,052 patients and found that total annual expenditure on dry eye treatment for year 2008 and 2009 exceeded US$1.5 million, and the total expenditure per patient visit in years 2008 and 2009 were US$22.11 and US$23.5957.

Indirect costs of DED due to work absenteeism (absence, early leaving) and presenteeism (equivalent lost work days because of affected performance, as proposed by Auren in 1955)58 to describe productivity loss when employees come to work but are not fully productive, were estimated to average $11,302 per year per patient with DED, with a corresponding overall US annual indirect cost burden of $55.4 billion54. Absenteeism from work averaged 8.4 days for patients with mild DED, to 14.2 days per year for severe DED patients54. Presenteeism was equivalent to 91 days for mild DED patients, 94.9 days for moderate DED patients, and 128.2 days for severe DED patients54 Reddy et al. also reported that patients with dry eye take 2–5 days off work annually, while they were present at work having symptoms for 191–208 days annually, indicating that presenteeism is a greater issue than absenteeism among those having dry eye59.

Another study from Japan evaluated the impact of dry eye on work productivity of office workers, especially in terms of presenteeism using a Work Limitations Questionnaire, an established tool for evaluation of presenteeism60. Among 396 individuals aged ≥20 years, the investigators showed that productivity in the group with self-reported DED was significantly lower than that in the control group (P ‹0.05). The annual cost of work productivity loss associated with DED was estimated to be USD $741 per person61. Another cross-sectional, web-based survey administered to 9034 individuals aged ≥18 years using the OSDI and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire62 showed work productivity loss was related to the severity of DED. Patients with moderate (18%) and severe (35%) DED had significantly greater reductions in work productivity than patients with mild (11%) disease. Similarly, impairment in ability to perform daily activities was significantly greater among respondents with severe disease (34%) than respondents with moderate (19%) or mild (12%) disease63.

Conclusion

DED is a common and growing problem that results in a multifaceted degradation of patients’ quality of life and visual performance. In this review, we have summarized the literature describing the impact of DED on patient’s QoL. Such studies consistently show that DED has a measureable impact on several aspects of patients’ QoL including pain, vitality, ability to perform certain activities requiring sustained visual attention (e.g. reading, driving), and reduced productivity in the workplace. Research also shows a substantial economic impact of DED as a result of these QoL impacts. Treatments for DED should therefore aim to improve patients’ QoL as this aspect of the disease appears to be the primary driver of its importance to both individual patients as well as society as a whole. It may be important to enhance awareness of dry eye among the society by educational activities.

Footnotes

Disclosure M. Uchino: none; D. A. Schaumberg: has served as a board member for SARcode Bioscience and Mimetogen, Inc., consultant for Eleven Biotherapeutics, Pfizer, Alcon, Allergan, Inspire Pharmaceuticals and Resolvyx, has grants/grants pending from Pfizer, has received payment for development of educational presentations from Allergan, and has stock/stock options with Tear Lab and Mimetogen.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- *1.The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2. This review paper provides the fundamental and essential points to define and classify dry eye disease.

- 2.Bjerrum KB. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and primary Sjogren’s syndrome in a Danish population aged 30-60 years. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1997;75:281–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1997.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schein OD, Munoz B, Tielsch JM, Bandeen-Roche K, West S. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:723–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarty CA, Bansal AK, Livingston PM, Stanislavsky YL, Taylor HR. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1114–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)96016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K. Results of a population-based questionnaire on the symptoms and lifestyles associated with dry eye. Cornea. 1999;18:408–11. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1264–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazdani C, McLaughlin T, Smeeding JE, Walt J. Prevalence of treated dry eye disease in a managed care population. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1672–82. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:318–26. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00218-6. This paper estimates the prevalence DED among US women using data obtained from a cohort of over 39,000 women

- 9.Guo B, Lu P, Chen X, Zhang W, Chen R. Prevalence of dry eye disease in Mongolians at high altitude in China: the Henan eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:234–41. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.498659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begley CG, Chalmers RL, Mitchell GL, et al. Characterization of ocular surface symptoms from optometric practices in North America. Cornea. 2001;20:610–8. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200108000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajagopalan K, Abetz L, Mertzanis P, et al. Comparing the discriminative validity of two generic and one disease-specific health-related quality of life measures in a sample of patients with dry eye. Value Health. 2005;8:168–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang FC, Tseng SH, Shih MH, Chen FK. Effect of artificial tears on corneal surface regularity, contrast sensitivity, and glare disability in dry eyes. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1934–40. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridder WH, 3rd, Tomlinson A, Paugh J. Effect of artificial tears on visual performance in subjects with dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:835–42. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000177803.74120.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto E, Ishida R, Kaido M, et al. Optical aberrations and visual disturbances associated with dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2006;4:207–13. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaido M, Dogru M, Ishida R, Tsubota K. Concept of functional visual acuity and its applications. Cornea. 2007;26:S29–35. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goto E, Yagi Y, Matsumoto Y, Tsubota K. Impaired functional visual acuity of dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:181–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaido M, Dogru M, Yamada M, et al. Functional visual acuity in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:917–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaido M, Ishida R, Dogru M, Tamaoki T, Tsubota K. Efficacy of punctum plug treatment in short break-up time dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:758–63. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181819f0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishida R, Kojima T, Dogru M, et al. The application of a new continuous functional visual acuity measurement system in dry eye syndromes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaido M, Matsumoto Y, Shigeno Y, Ishida R, Dogru M, Tsubota K. Corneal fluorescein staining correlates with visual function in dry eye patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9516–22. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montes-Mico R, Caliz A, Alio JL. Wavefront analysis of higher order aberrations in dry eye patients. J Refract Surg. 2004;20:243–7. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20040501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YY, Carrel H, Wang IJ, Lin PJ, Hu FR. Effect of tear film break-up on higher order aberrations of the anterior cornea in normal, dry, and post-LASIK eyes. J Refract Surg. 2005;21:S525–9. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20050901-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh S, Maeda N, Ninomiya S, et al. Paradoxical increase of visual impairment with punctal occlusion in a patient with mild dry eye. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:689–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denoyer A, Rabut G, Baudouin C. Tear film aberration dynamics and vision-related quality of life in patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Begley CG, Caffery B, Chalmers RL, Mitchell GL. Use of the dry eye questionnaire to measure symptoms of ocular irritation in patients with aqueous tear deficient dry eye. Cornea. 2002;21:664–70. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M, Gong L, Chapin WJ, Zhu M. Assessment of vision-related quality of life in dry eye patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:5722–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unlu C, Guney E, Akcay BI, Akcali G, Erdogan G, Bayramlar H. Comparison of ocular-surface disease index questionnaire, tearfilm break-up time, and Schirmer tests for the evaluation of the tearfilm in computer users with and without dry-eye symptomatology. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1303–6. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S33588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portello JK, Rosenfield M, Bababekova Y, Estrada JM, Leon A. Computer-related visual symptoms in office workers. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:375–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Catalan MR, Jerez-Olivera E. Benitez-Del-Castillo-Sanchez JM. [Dry eye and quality of life] Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84:451–8. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912009000900004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairchild CJ, Chalmers RL, Begley CG. Clinically important difference in dry eye: change in IDEEL-symptom bother. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:699–707. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181824e0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begley CG, Chalmers RL, Abetz L, et al. The relationship between habitual patient-reported symptoms and clinical signs among patients with dry eye of varying severity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4753–61. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjerrum KB. Test and symptoms in keratoconjunctivitis sicca and their correlation. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996;74:436–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitali C, Moutsopoulos HM, Bombardieri S. The European Community Study Group on diagnostic criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome. Sensitivity and specificity of tests for ocular and oral involvement in Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:637–47. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.10.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toda I, Fujishima H, Tsubota K. Ocular fatigue is the major symptom of dry eye. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993;71:347–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb07146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaumberg DA, Dana R, Buring JE, Sullivan DA. Prevalence of dry eye disease among US men: estimates from the Physicians’ Health Studies. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:763–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Miljanovic B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.060. This paper was among the first to demonstrate the impact of dry eye disease on vision related quality of life.

- 38.Tong L, Waduthantri S, Wong TY, et al. Impact of symptomatic dry eye on vision-related daily activities: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1486–91. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nease RF, Whitcup SM, Ellwein LB, Fox G, Littenberg B. Utility-based estimates of the relative morbidity of visual impairment and angina. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2000;7:169–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchholz P, Steeds CS, Stern LS, et al. Utility assessment to measure the impact of dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2006;4:155–61. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiffman RM, Walt JG, Jacobsen G, Doyle JJ, Lebovics G, Sumner W. Utility assessment among patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1412–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr., Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mertzanis P, Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, et al. The relative burden of dry eye in patients’ lives: comparisons to a U. S. normative sample. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:46–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Long-term incidence of dry eye in an older population. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:668–74. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318181a947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schein OD, Hochberg MC, Munoz B, et al. Dry eye and dry mouth in the elderly: a population-based assessment. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1359–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.12.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, Gutierrez P, Berry S, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) NEI-VFQ Field Test Investigators. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1496–504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Q, Zhou X, Ge L, Wu L, Hong J, Xu J. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life in a non-clinic-based general population. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nichols KK, Mitchell GL, Zadnik K. Performance and repeatability of the NEI-VFQ-25 in patients with dry eye. Cornea. 2002;21:578–83. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Mitchell GL. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea. 2004;23:762–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000133997.07144.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossi GC, Tinelli C, Pasinetti GM, Milano G, Bianchi PE. Dry eye syndrome-related quality of life in glaucoma patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:572–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leung EW, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Prevalence of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:350–5. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815c5f4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rolando M, Iester M, Macri A, Calabria G. Low spatial-contrast sensitivity in dry eyes. Cornea. 1998;17:376–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ridder WH, 3rd, Tomlinson A, Huang JF, Li J. Impaired visual performance in patients with dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2011;9:42–55. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30:379–87. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f7f363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clegg JP, Guest JF, Lehman A, Smith AF. The annual cost of dry eye syndrome in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom among patients managed by ophthalmologists. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:263–74. doi: 10.1080/09286580600801044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizuno Y, Yamada M, Shigeyasu C. Annual direct cost of dry eye in Japan. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:755–60. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S30625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waduthantri S, Yong SS, Tan CH, et al. Cost of dry eye treatment in an Asian clinic setting. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Auren U. How to build presenteeism. Petroleum Refiner. 1955;34:12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reddy P, Grad O, Rajagopalan K. The economic burden of dry eye: a conceptual framework and preliminary assessment. Cornea. 2004;23:751–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000134183.47687.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lerner D, Amick BC, 3rd, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The Work Limitations Questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39:72–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamada M, Mizuno Y, Shigeyasu C. Impact of dry eye on work productivity. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;4:307–12. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S36352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel VD, Watanabe JH, Strauss JA, Dubey AT. Work productivity loss in patients with dry eye disease: an online survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1041–8. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.566264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]