Abstract

We previously showed that betaxolol, a selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, administered during early phases of cocaine abstinence, ameliorated withdrawal-induced anxiety and blocked increases in amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor expression in rats. Here, we report the efficacy of betaxolol in reducing increases in gene expression of amygdalar corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a peptide known to be involved in mediating ‘anxiety-like’ behaviors during initial phases of cocaine abstinence. We also demonstrate attenuation of an amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated cell signaling pathway following this treatment. Male rats were administered betaxolol at 24 and 44 hours following chronic cocaine administration. Animals were euthanized at the 48 hour time-point and the amygdala was micro-dissected and processed for quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and/or Western blot analysis. Results showed that betaxolol treatment during early cocaine withdrawal attenuated increases in amygdalar CRF gene expression and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKA) regulatory and catalytic subunit (nuclear fraction) protein expression. Our data also reveal that β1-adrenergic receptors are on amygdalar neurons which are immunoreactive for CRF. The present findings suggest that the efficacy of betaxolol treatment on cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety may be related, in part, to its effect on amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor, modulation of its downstream cell signaling elements and CRF gene expression.

Keywords: beta-adrenergic receptor, norepinephrine, corticotropin-releasing factor, amygdala, cocaine withdrawal, anxiety

Introduction

Cessation of cocaine intake following chronic drug exposure is typically characterized by anxiety, depression, fatigue and agitation (NIDA, 2007). Importantly, anxiety induced during early phases of cocaine abstinence is often a provoking factor leading to relapse to cocaine use in human addicts (Gawin and Kleber, 1986; Koob and Bloom, 1988). Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is a neuropeptide widely distributed in extrahypothalamic-limbic brain areas, such as the amygdala, and has been implicated in mediating the ‘anxiety-like’ behavior that is observed in animals during the initial phase of cocaine abstinence (Sarnyai et al, 1995; Zhou et al, 2003). Animal studies have demonstrated that CRF protein expression is significantly elevated in the amygdala, a brain region rich in numerous CRF neurons, during early cocaine withdrawal (2 days) from chronic cocaine exposure (Sarnyai et al, 1995). Additionally, significant increases in amygdalar CRF gene expression have also been reported to occur in animals during this early withdrawal time-period (Zhou et al, 2003). Taken together, these findings indicate amygdalar CRF as a potential substrate underlying the expression of anxiety-like behavior that has been exhibited by animals during early cocaine withdrawal (Zhou et al, 2003).

The amygdala, a subcortical limbic structure that receives prominent noradrenergic innervation from the brainstem (Clayton and Williams, 2000; Pitkanen, 2000), shows a significant up-regulation of β1-adrenergic receptor expression following 2 days of withdrawal from chronic cocaine treatment (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). β1-adrenergic receptor expression levels return to that of controls following a more extended withdrawal period (12 days) (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). Interestingly, administration of the selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, betaxolol (Mosby, 2006), during early cocaine withdrawal significantly diminished cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety-like behavior in the animals and also reduced β1-adrenergic receptor expression levels such that they were comparable to controls (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). The β1-adrenergic receptor is coupled to Gs (stimulatory G-protein), an effect leading to increases in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels via activation of adenylate cyclase (Schultz and Daly, 1973). We postulated that downstream targets of the β1-adrenergic receptor, cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) regulatory subunit, PKA catalytic subunit, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and phosphorylated CREB (pCREB), would show alterations in expression in rat amygdala extracts following early cocaine withdrawal, as well as, following betaxolol treatment during early cocaine withdrawal. Therefore, we tested this hypothesis here. In order to evaluate the activation of PKA, we first performed an extraction procedure in which the nuclear compartment of our amygdalar micro-dissections were separated from cytoplasmic components. Next, we prepared these fractionated extracts for Western blotting, and probed them using antibodies targeted towards the regulatory and/or catalytic subunits of PKA.

To further elucidate gene targets accompanying cell signaling alterations in the amygdala, we focused on CRF gene expression. CRF is implicated in a number of drug abstinence syndromes and relapse to drug-seeking for multiple drugs of abuse, such as marijuana (Bruijnzeel and Gold, 2005), nicotine (Bruijnzeel et al, 2007), opioids (Sarnyai et al, 2001), alcohol (Menzaghi et al, 1994) and cocaine (Sarnyai et al, 1995; Weiss et al, 2001; Pollandt et al, 2006). Using quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), we examined CRF gene expression in the amygdala of rats during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration and following betaxolol treatment. Lastly, implicit to our hypothesis is the localization of β1-adrenergic receptor to amygdalar CRF-containing neurons, which has not heretofore been reported. Sections through the forebrain of male Sprague Dawley rats were processed for the dual immunocytochemical detection of β1-adrenergic receptor and CRF using confocal fluorescence and electron microscopy.

Materials and Methods

Animal Use and Care

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN; age ≥ 60 days old, 250–274 g) were used in this study. The animal procedures used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Thomas Jefferson University and conform to National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rats were housed two per cage on a 12-h light schedule (lights on at 7:00 am) in a temperature-controlled (20°C) colony room and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the facility for 7 days prior to the start of the study. All efforts were made to minimize animal pain and suffering and reduce the number of animals used in these studies.

Drug Treatment

Cocaine hydrochloride (supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD) was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride (saline) solution at a concentration of 20 mg/ml. For the two day withdrawal experiments, animals were randomly assigned to two treatment groups at the beginning of the study. One half of the animals were administered cocaine once daily at a dosage of 20 mg/kg via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection for 14 days, while the other half of the animals received once daily i.p. injections of saline solution (1 ml/kg) for 14 days. Subsequent to the 14 day drug administration period, animals were randomly sorted into the four distinct treatment groups based on the treatment they would receive during the 48 hour withdrawal period. The four treatment groups are described in Table 1. The 48-hour time period following cessation of chronic cocaine administration has been shown in previous studies to be the point when cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety is at its peak (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993; Sarnyai et al, 1995).

Table 1.

Drug Treatment Groups

| Drug Treatment: (14 days, 1x daily, i.p.) | 24 hrs after Final Drug Treatment (i.p.) | 44 hours after Final Drug Treatment (i.p.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group SS | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) |

| Group CS | Cocaine (20 mg/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) |

| Group SB | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) |

| Group CB | Cocaine (20 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) |

As indicated in Table 1, two groups of animals received betaxolol hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.9 % sodium chloride (5 mg/ml) and two groups received only saline (1 ml/kg) via i.p. injection during the withdrawal period. The first dose of betaxolol was administered 24 hours after the final treatment of chronic cocaine or saline. Another dose of betaxolol was administered at 44 hours following cessation of chronic cocaine administration. Animals were euthanized at the 48 time-point for the purposes of Western blot analysis and/or qRT-PCR experiments. The dose of betaxolol administered (5 mg/kg) was chosen based on dose response studies from our laboratory. This specific dose used in the present study has been shown to be effective in ameliorating cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior in animals (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006).

Protein Extraction

Animals were briefly exposed to isoflurane and then euthanized by decapitation. Brain tissue was rapidly removed on ice from each animal and using a trephine and razor blades, the amygdala brain region (approximately 0.02 g wet weight) was micro-dissected from each (see Supplemental Figure 1). The amygdala was homogenized with a pestle and extracted in RadioImmunoPrecipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) on ice for 20 min. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 12 min at 4 °C.

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction

Animals were briefly exposed to isoflurane and then euthanized by decapitation. Brain tissue was rapidly removed on ice from each animal and using a trephine and razor blades, the amygdala brain region (approximately 0.02 g wet weight) was micro-dissected from each. Lysates containing the nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions of each sample were prepared using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Western Blotting

Supernatants or protein extracts were diluted with an equal volume of Novex® 2X Tris-Glycine Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing dithiothreitol (DTT; Sigma). Protein concentrations of the undiluted supernatants were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated on 4–12% Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gels. Whole (un-fractionated) extracts, cytoplasmic extracts and nuclear extracts were loaded onto separate gels at 20 μg, 15 μg and 5 μg per lane, respectively. Next, gels were electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated in PKA regulatory subunit (1.5 μg/ml; Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY), PKA catalytic subunits (1 μg/ml, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), pCREB (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), CREB (2.5 μg/ml; Abcam Inc.) or TATA binding protein (1:2000; Abcam Inc.) primary antibodies (a minimum of two hours) and then alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibodies for 30 minutes in order to probe for the presence of proteins using a Western blotting detection system (Western Breeze Chemiluminescent Kit, Invitrogen). Following incubation in a chemiluminescent substrate (Western Breeze Chemiluminescent Kit, Invitrogen), blots were exposed to X-OMAT AR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for different lengths of time to optimize exposures. PKA regulatory subunit, PKA catalytic subunit, pCREB, CREB and TATA binding protein expression were readily detected by immunoblotting in rat amygdala extracts, and each were visualized as a single band that migrated at approximately 52, 42, 43, 43 and 38 kDa, respectively. Blots were incubated in stripping buffer (Restore Stripping Buffer, Pierce) to disrupt previous antibody-antigen interactions and then re-probed with β-actin antibody (1:5000; 1 hour incubation, Sigma) to ensure proper protein loading. The band densities of the western blots were quantified using Un-Scan-It blot analysis software (Silk Scientific Inc., Orem, Utah). PKA regulatory subunit and PKA catalytic subunit immunoreactivity was normalized to β-actin immunoreactivity for each animal. pCREB immunoreactivity was evaluated relative to CREB immunoreactivity for each animal.

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Animals (n=6–8 per treatment group; see Table 1) were briefly exposed to isoflurane and then euthanized by decapitation. Brain tissue was rapidly removed on ice from each animal and using a trephine and razor blades, the amygdala and frontal cortex brain regions (approximately 0.02 g wet weight) were micro-dissected from each. Total RNA was extracted from these regions using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Residual genomic DNA was digested in these extracts with DNA-free™ DNase Treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX) at room temperature for 30 min. RNA extracts were spectrophotometrically quantitated and cDNAs were synthesized from 2 μg of each RNA extract using oligo (dT) primer and the Omniscript® Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, cDNAs were stored at −20 °C.

Primer sequences were designed for CRF to contain minimal internal structures (i.e. primer dimers) using the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primer sequences used for CRF were as follows: 5′-GGCCAGGGCAGAGCAGTT (forward) and 5′-GGCCAAGCGCAACATTTC (reverse). The housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH), was used as an internal control since this gene is constitutively expressed at high levels in most tissues. A QuantiTect Primer Assay was used for amplification of GAPDH (Qiagen).

Thermal cycling, SYBR Green fluorescence detection and data collection was done in a real-time PCR thermal cycler (ABI 7500 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems). Each 25 ul PCR reaction consisted of 1 μl RT product, 1 μM each of forward and reverse CRF primers or 10X GAPDH primer assay (according to manufacturer’s instructions) and 12.5 μl SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. A dissociation analysis was performed after the final PCR cycle to verify that nonspecific PCR products were not generated during the PCR run. Additionally, validation experiments using dilutions of untreated sample verified that amplification efficiencies of both CRF and the housekeeping gene were approximately equal.

Data collected by the ABI 7500 Sequence Detection System was expressed as a function of threshold cycle (CT), which represents the PCR cycle at which an increase in SYBR Green fluorescence above a base line signal can be first detected. Relative quantitative gene expression was calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT method described in Livak and Schmittgen, 2001 (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). For each sample, the CT for reactions amplifying the gene of interest and the housekeeping gene were determined. The CT value of CRF for each sample was normalized by subtracting the CT value of GAPDH (ΔCT). Saline controls were used as reference samples with mean ΔCT for the control sample being subtracted from the ΔCT for all of the other experimental samples (ΔΔCT). Lastly, CRF mRNA abundance in experimental groups was calculated relative to CRF mRNA abundance in control samples using the formula 2−ΔΔCT.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the Western blotting data was performed on the normalized densitometry values using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test. For the qRT-PCR data, average differences in cycle thresholds were analyzed between treatment groups using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test. Significance for all statistical tests was set at p<0.05.

Immunofluorescent Histochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

Animals (n=5) were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused through the ascending aorta with heparin (1000 units/ml) followed by 4% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) (Van Bockstaele et al, 1989). The brains were extracted, and 40 μm-thick coronal sections were cut through the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala (Paxinos and Watson, 1986) using a Vibratome (Technical Product International, St. Louis, MO) and collected into chilled 0.1 M PB.

Tissue sections of the amygdala were incubated in 1% sodium borohydride solution for 30 min to remove reactive aldehydes. They were rinsed in 0.1 M PB and 0.1 M tris–saline buffer (TS; pH 7.6). Sections were then blocked in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.1 M TS for 30 min and rinsed extensively in 0.1 M TS. Tissue sections were incubated in a cocktail of rabbit anti-β1-adrenergic receptor (1:1000; Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA) and guinea pig anti-CRF (1:2000; Peninsula Laboratories, Inc., San Carlos, CA) primary antibodies made in 0.1 M TS containing 0.1% BSA at room temperature overnight on a rotary shaker. Subsequently, tissue sections were rinsed in 0.1 M TS and then incubated in a cocktail of fluorescein isothiocyanate donkey anti-rabbit (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and rhodamine isothiocyanate donkey anti-guinea pig (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc.) secondary antibodies made in 0.1 M TS containing 0.1% BSA (3 hrs). Lastly, tissue sections were rinsed in 0.1 M TS and mounted onto gelatinized slides. The sections were air-dried in an enclosure protected from light. Once dry, the slides were dehydrated in a series of alcohols, ending in xylene and coverslipped using DPX (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Immunofluorescence labeling was analyzed on the sections using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany). Images of fluorescent labeling of the sections were captured and dual fluorescence merged images were generated by the confocal microscope.

Immunoelectron Microscopy and Electron Microscopy

Rats (n=5) were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially through the ascending aorta with 10 ml heparinized saline followed by 50 ml of 3.75% acrolein (Electron Microscopy Sciences), and 200 ml of 2% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4). The brains were immediately removed and sectioned into 1–3 mm coronal slices. The slices were post-fixed for 30 min and 40 μm-thick sections were cut through the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala using a Vibratome and collected into chilled 0.1 M PB. Forty-μm thick sections through the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala were processed for electron microscopic analysis of β1-adrenergic receptor and CRF in the same sections and were processed following the same protocol described above for immunofluorescent histochemistry until the point of the secondary antibody incubation.

Tissue sections were incubated in a primary antibody cocktail of rabbit anti-β1-adrenergic receptor (1:1000; Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA) and guinea pig anti-CRF (1:2000; Peninsula Laboratories, Inc.) for 15–18 h at room temperature. The following day, tissue sections were rinsed three times in 0.1 M TS, incubated in biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit (1:400; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc.) and biotinylated donkey anti-guinea pig (1:400; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min, and then rinsed again in 0.1 M TS. Next, sections underwent a 30 min incubation in an avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). CRF immunoreactivity was visualized by a 6 min reaction in 22 mg of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) and 10 μl of 30% hydrogen peroxide in 100 ml of 0.1 M TS. Sections were continuously agitated with a rotary shaker during all aforementioned incubations and washes.

For gold-silver localization of β1-adrenergic receptor, sections were rinsed three times with 0.1 M TS, followed by rinses with 0.1 M PB and 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). Sections were then incubated in a 0.2% gelatin-PBS and 0.8% BSA buffer for 10 min. Subsequently, sections were incubated in 1nm gold anti-rabbit antibody (1:50; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at room temperature for 2 hours. Next, sections were rinsed in 0.2% gelatin-PBS and 0.8% BSA buffer and followed by a rinse in 0.01 M PBS. Sections were then incubated in 2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.01 M PBS for 10 min followed by washes in 0.01 M PBS and 0.2 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.4). A silver enhancement kit (Amersham Biosciences) was used for silver intensification of the gold particles. The optimal times for silver enhancement time were determined by empirical observation but ranged from 12–15 min. Following silver intensification, tissue sections were rinsed in 0.2 M citrate buffer and 0.1 M PB, incubated in 2% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M PB for 1 h, washed in 0.1 M PB, dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol followed by propylene oxide and flat embedded in Epon 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) (Leranth and Pickel, 1989; Van Bockstaele and Pickel, 1993).

Flat embedded tissue sections were mounted onto Epon capsules and thin sections approximately 50–100 nm in thickness were cut with a diamond knife (Diatome-US, Fort Washington, PA, USA) using a Leica Ultracut (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were collected on copper mesh grids and examined with a Hitachi electron microscope. Digital electron micrographic images were collected and figures were assembled using Adobe Photoshop.

The cellular elements (cell bodies, dendrites, axon terminals) were identified based on the description of Peters and colleagues (Peters et al, 1991). A terminal was considered to form a synapse if it showed synaptic vesicles near a restricted zone of parallel membranes with slight enlargement of the intercellular space, and/or associated with postsynaptic thickening. Asymmetric synapses were identified by thick postsynaptic densities (Gray’s type I) (Gray, 1959), in contrast, symmetric synapses had thin densities (Gray’s type II) (Gray, 1959) both pre-and postsynaptically. A non-synaptic apposition was defined as an axon terminal plasma membrane juxtaposed to that of a dendrite or soma devoid of recognizable membrane specializations and no intervening glial processes.

Results

Betaxolol blocks cocaine withdrawal-induced increases in amygdalar PKA regulatory subunit expression

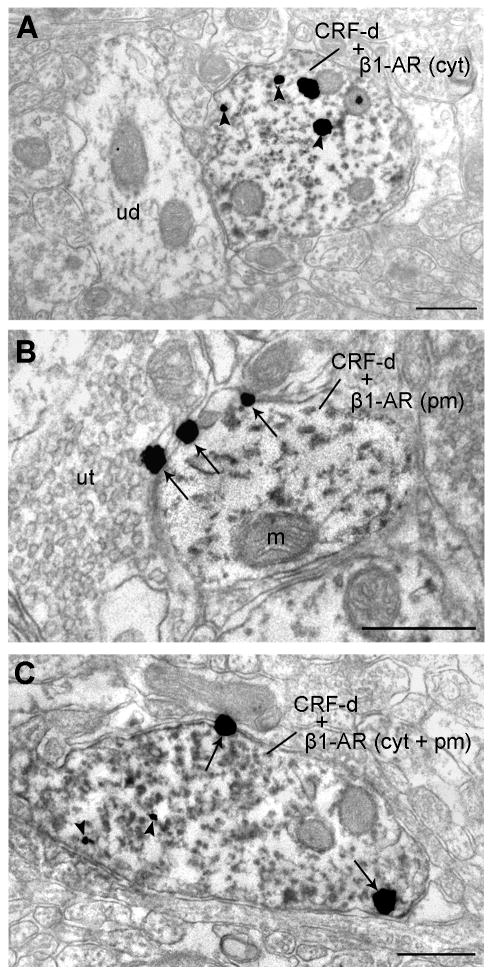

A one-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated a significant difference among treatment groups (see Table 1; n=5/treatment group) in PKA regulatory subunit expression by western blot analysis [p=0.0284, F(3,16)=3.916] and post-hoc comparison tests among these groups revealed the differences. In Figure 1, amygdalar PKA regulatory subunit immunoreactivity of the groups of animals is expressed as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.). Amygdala extracts from animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal with no betaxolol treatment (CS) exhibited a significant increase (p<0.05) in PKA regulatory subunit protein expression compared to saline control animals (SS). Likewise, PKA regulatory subunit immunoreactivity was significantly greater (p<0.05) in cocaine withdrawn animals (CS) compared to animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB). However, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in PKA regulatory subunit protein expression levels between animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol (SS) and animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB). Betaxolol administration had a significant effect on PKA regulatory subunit expression in the amygdala of animals that underwent cocaine withdrawal (CB), as amygdala extracts from those animals displayed a significant decrease (p<0.05) in PKA regulatory subunit expression compared to cocaine administered animals that did not receive betaxolol treatment during withdrawal (CS). Also of importance, amygdala extracts from animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (CB) exhibited similar levels of PKA regulatory subunit protein expression as animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol treatment (SS; p>0.05), and also animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB; p>0.05). Statistical significance is indicated on graph; * p<0.05 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Western blots demonstrating PKA Regulatory Subunit immunoreactivity in the amygdala of animals from four different drug treatment groups (see Table 1). PKA Regulatory Subunit immunoreactivity in the amygdala of these animals is expressed as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.). PKA regulatory subunit expression is elevated in the amygdala following early cocaine withdrawal, however; this effect is reversed following betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal. Statistical significance between groups of animals is indicated on graph; * p<0.05.

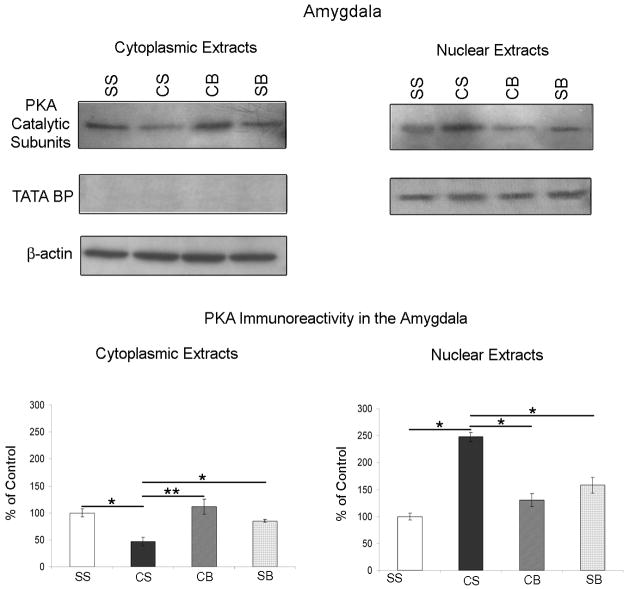

Betaxolol reverses cocaine withdrawal-induced alterations in PKA catalytic subunit expression in amygdalar cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts

By ANOVA analysis, there was a significant difference among treatment groups (see Table 1; n=5/treatment group) in PKA catalytic subunit expression in both cytoplasmic [p=0.0085; F(3,16)=5.523] and nuclear [p=0.0166; F(3,16)=4.601] amygdalar extracts. PKA catalytic subunit immunoreactivity in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear amygdalar extracts was plotted as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.; Figure 2). Amygdala cytoplasmic extracts from animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal with no betaxolol treatment (CS) exhibited a significant decrease (p<0.05) in PKA catalytic subunit protein expression compared to saline control animals (SS; bottom left). Alternatively, PKA catalytic subunit expression was significantly elevated (p<0.05) in nuclear extracts from CS animals compared to controls (SS; bottom right), indicating the likely translocation of PKA catalytic subunit from the cytoplasm to the nuclear compartment during early cocaine withdrawal. Cytoplasmic and nuclear amygdalar extracts from animals receiving betaxolol administration during cocaine withdrawal (CB; both left and right bottom) demonstrated a reversal of these alterations in PKA catalytic subunit protein levels. Hence, following betaxolol treatment (CB), PKA catalytic subunit expression was returned to levels comparable to those of control animals (SS) in both cytoplasmic and nuclear amygdalar extracts. Statistical significance between groups of animals is indicated on graphs; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Western blots demonstrating PKA Catalytic Subunit and the nuclear localization marker, TATA Binding Protein (BP), expression in cytoplasmic (top left) and nuclear (top right) amygdalar extracts obtained from four different groups of drug treated animals (see Table 1). In both the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, PKA Catalytic Subunit immunoreactivity in the amygdala of these animals is expressed as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.). PKA catalytic subunit expression was significantly decreased in amygdalar cytoplasmic extracts and concurrently increased significantly in amygdalar nuclear extracts from animals that underwent cocaine withdrawal. Betaxolol administration during early cocaine withdrawal reversed alterations in PKA catalytic subunit expression in amygdalar cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts to control levels. Statistical significance between groups of animals is indicated on graphs; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. TATA BP immunoreactivity was used as a nuclear loading control. Cytoplasmic extracts lack immunoreactivity for TATA BP, while nuclear extracts demonstrate TATA BP immunoreactivity. β-actin immunoreactivity was evaluated in cytoplasmic amygdalar extracts (top left) as a loading control.

Critical to the significance of the alterations in expression of PKA catalytic subunit that we demonstrated in these studies was the precision of the nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction procedure. In order to confirm that our extracts contained only the nuclear or cytoplasmic cellular fractions as desired, we probed blots containing these extracts with an antibody targeted towards TATA Binding protein. TATA Binding protein is a DNA binding protein that binds specifically to the TATA box found in gene promoters, and is vital to the initiation of all eukaryotic transcription (Moore et al, 1999). Hence, TATA Binding protein makes a useful loading control for nuclear extracts (Kwintkiewicz et al, 2007). TATA Binding protein immunoreactivity was detected in nuclear extracts from all treatment groups (Figure 2).

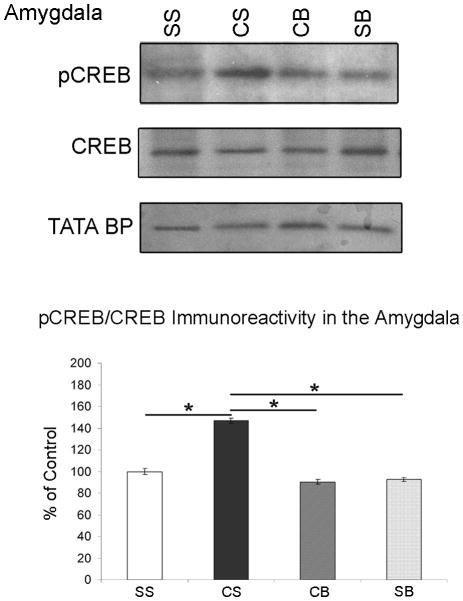

Betaxolol blocks cocaine withdrawal-induced increases in CREB phosphorylation in amygdalar nuclear extracts

A significant difference was found between groups (see Table 1, n=5/treatment group) in CREB phosphorylation in amygdalar nuclear extracts [p=0.0354, F(3,16)=3.650]. pCREB protein densitometry levels were evaluated relative to CREB densitometry levels for each animal. pCREB/CREB immunoreactivity in the amygdala of these animals was plotted as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.; Figure 3). Amygdala extracts from animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal with no betaxolol treatment (CS) exhibited a significant increase (p<0.05) in CREB phosphorylation compared to saline control animals (SS). Likewise, pCREB immunoreactivity was significantly greater (p<0.05) in cocaine withdrawn animals (CS) compared to animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB). There was no significant difference (p>0.05) in pCREB protein levels between animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol (SS) and animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB). Amygdala extracts from animals that were administered betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (CB) displayed a significant decrease (p<0.05) in CREB phosphorylation compared to cocaine administered animals that did not receive betaxolol treatment during withdrawal (CS). Amygdala extracts from CB animals exhibited similar levels of pCREB protein as saline control animals (SS; p>0.05), and also animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (SB; p>0.05).

Figure 3.

Western blots demonstrating pCREB, CREB, and the nuclear localization marker, TATA BP, immunoreactivity in the amygdala of animals from four different drug treatment groups (see Table 1). pCREB protein densitometry levels were evaluated relative to CREB protein densitometry levels for each animal. pCREB/CREB immunoreactivity in the amygdala of these animals is expressed as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100 (±S.E.M.). CREB phosphorylation is increased in amygdalar nuclear extracts following early cocaine withdrawal, however; betaxolol administration during early cocaine withdrawal blocks this increase. Statistical significance between groups of animals is indicated on graph; * p<0.05.

TATA binding protein (BP) immunoreactivity was used as a nuclear loading control in these experiments. Cytoplasmic extracts lack immunoreactivity for TATA BP, while nuclear extracts demonstrate TATA BP immunoreactivity (Figure 3).

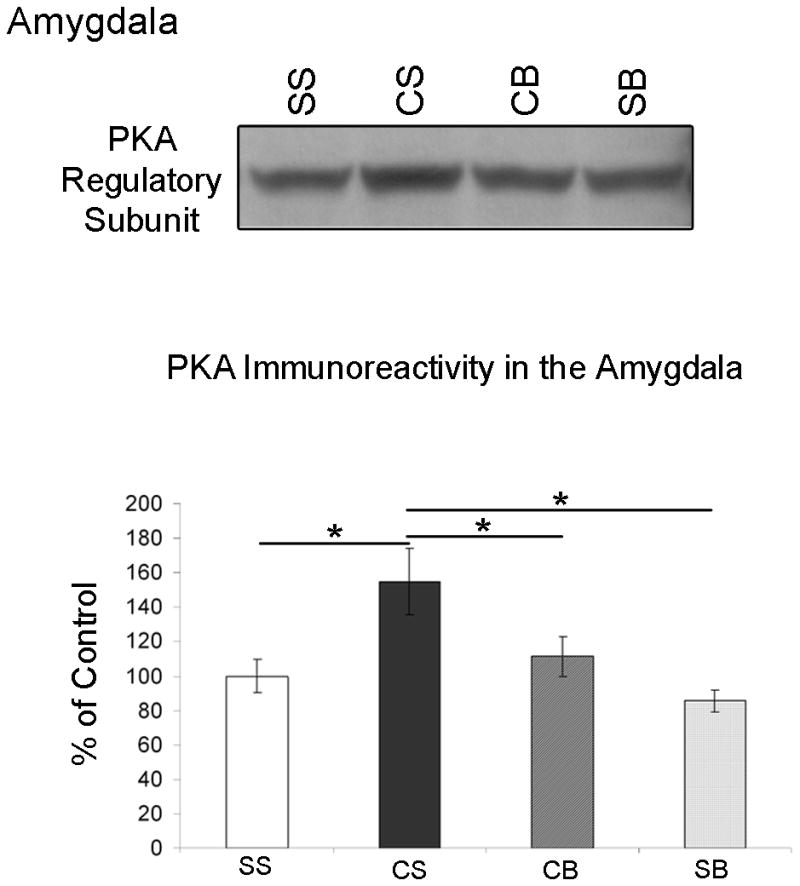

Betaxolol attenuates cocaine withdrawal-induced increases in amygdalar CRF mRNA levels

Data from the RT-PCR experiments was analyzed by the comparative CT method using the formula 2−ΔΔCT. Fold change differences in CRF mRNA abundance in the three drug treatment groups (CS, SB and CB; see Table 1) were plotted relative to saline control (SS) when the saline control group equals 1 (Figure 4). Comparison of average threshold cycles for CRF between the treatment groups using one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in CRF mRNA expression between the groups [see Table 1; p=0.0156, F(3,22)=4.306] and post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test detailed these differences. Confirming reports of others (Zhou et al, 2003), our data demonstrated that CRF mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in amygdalar extracts from animals following early cocaine withdrawal (Figure 4, CS vs. SS; p<0.05). However, this increase was blocked in amygdalar extracts from animals that were treated with betaxolol following cocaine administration (CB vs. CS, p<0.05). Betaxolol treatment alone did not have any significant effect on amygdalar CRF mRNA expression (SB vs. SS; p>0.05). Using qRT-PCR, we also examined CRF mRNA expression levels in frontal cortex micro-dissections that we extracted from animals from the four drug treatment groups (see Table 1). From these experiments, we found no statistically significant difference in CRF mRNA expression levels in frontal cortex extracts among these groups (data not shown). Collectively, the Western blotting and qRT-PCR data from the present study suggest that betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal may block increases in amygdalar CRF gene expression by attenuating an amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated cell signaling pathway (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal on CRF mRNA levels in the amygdala. Quantitative RT-PCR data was analyzed by the comparative CT method using the formula 2−ΔΔCT. Fold change differences in CRF mRNA abundance in the three drug treatment groups (CS, SB and CB; see Table 1) are plotted relative to saline control (SS) when the saline control group equals 1. CRF mRNA expression was significantly increased in amygdalar extracts from animals following early cocaine withdrawal (CS vs. SS); however, this increase was attenuated in amygdalar extracts from animals that were treated with betaxolol following cocaine administration (CB vs. CS). Betaxolol treatment alone did not have any significant effect on amygdalar CRF mRNA expression (SB vs. SS). Statistical significance between groups of animals is indicated on graph; * p<0.05.

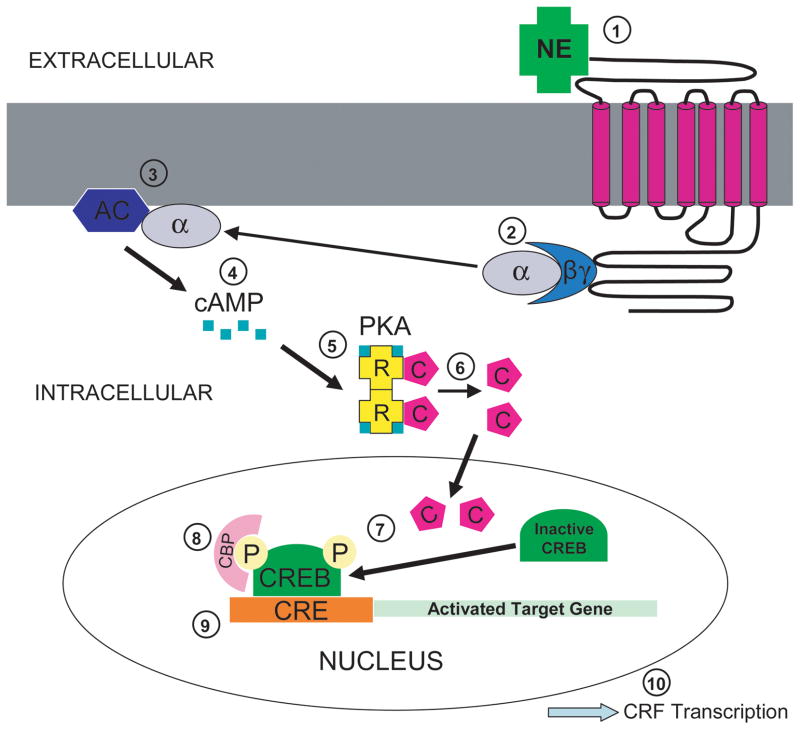

Figure 5.

Proposed cell signaling pathway of noradrenergic influence on CRF transcription. Norepinephrine (NE) in the extracellular space binds to a G-protein coupled adrenergic receptor spanning the neuronal cell membrane (1). This ligand-receptor complex then activates the G protein, causing the alpha subunit to dissociate from the beta and gamma subunits (2). The activated alpha subunit of the G protein functions to activate the plasma membrane bound enzyme, adenylyl cyclase (3). Adenylyl cyclase synthesizes cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (4). cAMP binds to the regulatory subunits of cycle-AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) (5). This induces a conformational change causing the regulatory subunits to release the catalytic subunits, thereby activating the kinase activity of the catalytic subunits (6). Once the catalytic subunits are freed and active, they translocate into the nucleus of the cell to phosphorylate cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) (7). The regulatory subunits remain in the cytoplasm. Phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) then recruits a transcriptional co-activator called CREB-binding protein (CBP) (8). CBP recognizes the regulatory region of the target gene called the cAMP response element (CRE) and stimulates gene transcription (9). The culmination of this proposed cell signaling pathway is the transcription of CRF (10).

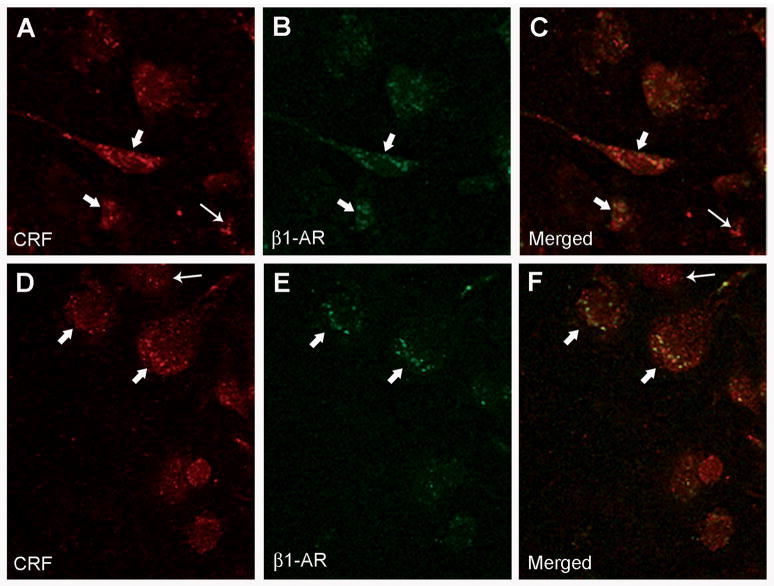

β1-adrenergic receptors are located on numerous CRF-containing neurons of the CNA

β1-adrenergic receptors were frequently observed on CRF-containing neurons of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA) and this observation was made using both confocal and electron microscopy. For immunofluorescent confocal microscopy, rat brain tissue sections containing the amygdala were labeled for CRF using rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody, while β1-adrenergic receptors were labeled using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody. Using confocal microscopy, CRF immunoreactivity was characterized as a diffuse red fluorescent product and was localized to cell bodies (Figure 6, A and D; thick white arrows), whereas β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was visualized as a punctate green fluorescent label also localized to perikarya (Figure 6, B and E; thick white arrows). When the fluorescent images were merged, dual labeling for both CRF and β1-adrenergic receptor was identified as a yellow fluorescent label (Figure 6, C and F; thick white arrows). Not all CRF-labeled cells in the CNA contained labeling for β1-adrenergic receptor (Figure 6, A, C, D and F; thin white arrows) and we also observed some β1-adrenergic receptor labeling not on CRF neurons.

Figure 6.

β1-adrenergic receptors are located on CRF-containing neurons of the amygdala. A and D: High magnification confocal photomicrographs of two separate coronal sections through the CNA labeled for CRF using rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody; thin arrows point to CRF-immunoreactive cells, while thick arrows indicate CRF-immunoreactive perikarya containing β1-adrenergic receptors (see panels C and F). B and E: The same coronal sections as shown in figures A and D, respectively, labeled for β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR) using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody; thick arrows indicate CRF-immunoreactive perikarya containing β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR) (see panels C and F). C and F: Merged images of panels A and B and D and E, respectively. Thick arrows show immunoreactivity for CRF and β1-adrenergic receptors, while thin arrows indicate single-labeling for CRF only.

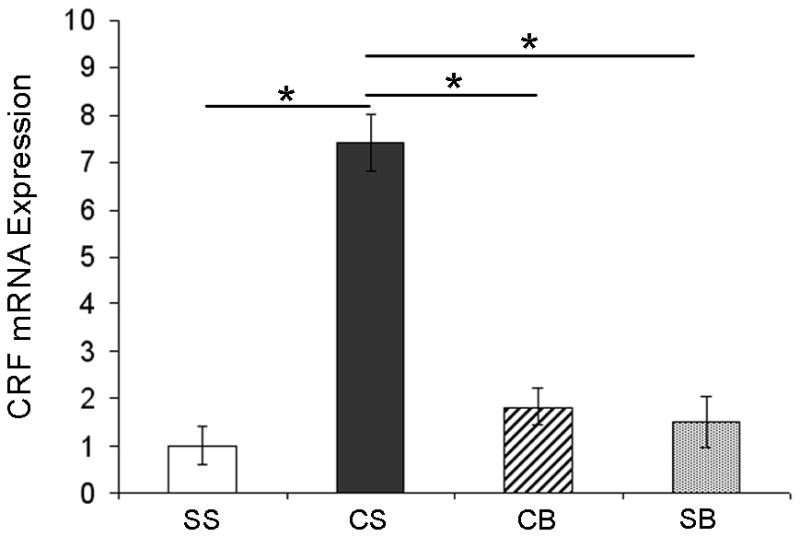

Using electron microscopy, we observed ultrastructural evidence for co-localization of β1-adrenergic receptors and CRF in the amygdala. CRF immunoreactivity was identified by an electron-dense peroxidase reaction product and β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was visualized as immunogold-silver particles. A profile was considered to be positive for immunogold particle labeling only if three or more immunogold particles were present in the same profile. CRF and β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivities were sometimes observed in separate dendrites in the same neuropil (Figure 7, A), but were often observed co-localized in the same dendrites of the CNA (Figure 7, B and C). We quantified the frequency of co-localization and found that of the profiles exhibiting immunoreactivity for β1-adrenergic receptor (n=474), 45% of these profiles also contained CRF labeling. Furthermore, of the profiles exhibiting CRF immunoreactivity (n=389), 55% of these profiles also contained β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity. We also observed that dendrites of co-localized CRF and β1-adrenergic receptors form both asymmetric (curved arrows) and symmetric (double arrows) synapses with axon terminals (Figure 7, B and C).

Figure 7.

Ultrastructural evidence for co-localization of β1-adrenergic receptors and CRF in the amygdala. A: Electron photomicrograph showing a dendrite containing immunogold-silver labeling (arrowheads) for β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR). A dendrite containing peroxidase labeling (arrows) for CRF (CRF-d) can also be identified in the neuropil. Scale bar: 0.50 μm. B–C: Electron photomicrographs showing CRF (CRF-d; immunoperoxidase) and β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR; immunogold) immunoreactivities co-localized in dendrites of the CNA. Arrowheads indicate immunogold particles for β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR) and peroxidase labeling for CRF (CRF-d; arrows) is identified as electron-dense reaction product. Dendrites of co-localized CRF and β1-adrenergic receptors form asymmetric (curved arrows) and symmetric (double arrows) synapses with axon terminals. Scale bars: 0.50 μm. Abbreviations: m, mitochondria; ut, unlabeled terminal.

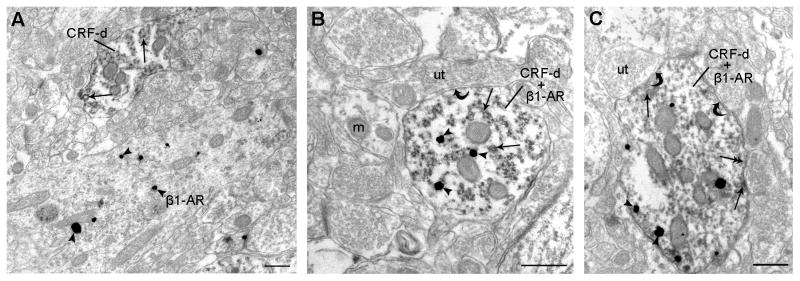

By electron microcopy, we also investigated the distribution of β1-adrenergic receptors in CRF-immunoreactive dendritic processes in the amygdala. β1-Adrenergic receptors were found located within the cytoplasmic compartment and also distributed along the plasma membrane of CRF-immunoreactive dendrites (Figure 8). We quantified the frequency of localization of β1-adrenergic receptor labeling either on the plasma membrane versus within the cytoplasm of CRF-labeled profiles and determined that 62.3% of our dual CRF and β1-adrenergic receptor -labeled profiles exhibited β1-adrenergic receptor labeling on the plasma membrane, while 37.7% of these profiles demonstrated β1-adrenergic receptor labeling within the cytoplasm.

Figure 8.

Distribution of β1-adrenergic receptors in CRF-immunoreactive dendritic processes in the amygdala. A: β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR cyt) are shown located within the cytoplasmic compartment of a CRF-immunoreactive dendrite (CRF-d). B: β1-adrenergic receptors (β1-AR pm) are shown distributed along the plasma membrane of a CRF-immunoreactive dendrite (CRF-d). C: Some β1-adrenergic receptors are located within the cytoplasmic compartment, while some are located along the plasma membrane (β1-AR cyt + pm) of a CRF-immunoreactive dendrite (CRF-d). Arrowheads indicate immunogold labeling for β1-adrenergic receptors within the cytoplasmic compartment, while arrows point to β1-adrenergic receptors along the plasma membrane. Scale bars: 0.50 μm. Abbreviations: ud, unlabeled dendrite; m, mitochondria; ut, unlabeled terminal.

Discussion

Our previous studies demonstrated increased amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor expression during early cocaine withdrawal (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). The present study extends these previous results by showing that alterations in amygdalar cell signaling and amygdalar CRF gene expression accompany these alterations. We further demonstrate that treatment with betaxolol, a selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist (Mosby, 2006), during early cocaine withdrawal (2 days) blocks increases in a β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated cell signaling pathway and CRF gene expression. These data suggest a potential cellular mechanism underlying the efficacy of betaxolol in the treatment of cocaine withdrawal. These findings could have important implications in the pursuit of potential pharmacotherapies for the treatment of withdrawal-induced anxiety following cocaine addiction.

Early periods of withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration are accompanied by significant anxiety-like behavior (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993; Sarnyai et al, 1995; Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). This behavior has been attributed, in part, to increases in both amygdalar CRF gene expression (Sarnyai et al, 1995; Zhou et al, 2003) and β1-adrenergic receptor expression (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006). The hypothesis that β1-adrenergic receptors localized to amygdalar CRF neurons play an important role in withdrawal-induced anxiety is emerging as it has already been established that norepinephrine and CRF systems interact in the brain to modulate stress responses (Valentino et al, 1991; Valentino et al, 1993; Li et al, 1998; Koob, 1999; Van Bockstaele et al, 1999).

Activation of β1-adrenergic receptors stimulates Gs, and this, in turn, results in an increase in intracellular cAMP levels (Schultz and Daly, 1973) (see Figure 5). Accumulation of intracellular cAMP (Montminy, 1997) results in PKA activation, whereby, the binding of cAMP causes PKA regulatory subunits to alter their conformation, and the catalytic subunits to dissociate from the complex (Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989; Gonzalez et al, 1991; Alberts et al, 2002). The catalytic subunits translocate into the nucleus to phosphorylate specific substrate protein molecules, such as CREB, while the regulatory subunits remain in the cytoplasm (Gonzalez and Montminy, 1989; Gonzalez et al, 1991; Siegal et al, 1999; Purves et al, 2001; Alberts et al, 2002).

Our results showing an increase in PKA catalytic subunit expression in nuclear amygdalar extracts and a simultaneous decrease in PKA catalytic subunit expression in cytoplasmic amygdalar extracts from rats following cocaine withdrawal suggest a translocation of the PKA catalytic subunits to the nucleus. This translocation indicates PKA activation (Asyyed et al, 2006). Interestingly, the expression of PKA regulatory subunit was significantly increased in whole amygdalar extracts during this time period also. The alteration in PKA we observed was accompanied by a significant increase in CREB phosphorylation in amygdalar nuclear extracts, while overall CREB levels remained unchanged. Our finding demonstrating increases in CREB phosphorylation further supports activated PKA in our cocaine withdrawn animals, as phosphorylation of CREB at Ser-133 occurs in response to PKA activation (Montminy, 1997; Mayr and Montminy, 2001; Johannessen et al, 2004).

Activation of PKA within the amygdala is thought to contribute to the synaptic plasticity and reward-related learning that underlies pathologic behavior in drug addicted individuals (Robbins and Everitt, 1999; Berke and Hyman, 2000; Jentsch et al, 2002). Jentsch et al. demonstrated that intra-amygdalar infusions of Sp-cAMP, which activates PKA, in rats produces concentration-dependent enhancements of the acquisition of approach to a conditioned stimulus that predicts water availability (Jentsch et al, 2002). A similar effect was produced in animals using intra-amygdalar infusion of cholera toxin, which elevates cAMP levels. On the contrary, intra-amygdalar infusions of Rp-cAMPS, an inhibitor of PKA, impaired acquisition of approach behavior (Jentsch et al, 2002). Modulation of PKA activation in other brain regions, such as the nucleus accumbens, has also been specifically associated with cocaine self-administration (Self et al, 1998) and motivation to obtain cocaine (Lynch and Taylor, 2005). In rats self administering cocaine under a fixed ratio 1 schedule (each response produces an infusion of cocaine), activation of PKA in the nucleus accumbens produced increases in levels of cocaine intake whereas, inhibition produced a decrease in total intake (Self et al, 1998). After extinction from cocaine self-administration, infusions of Sp-cAMPS into the nucleus accumbens induced generalized responding at both drug-paired and inactive levers and increased phosphorylation of CREB (Self et al, 1998). In another study, bilateral infusions of Sp-cAMPS resulted in an increase in progressive ratio responding for cocaine, whereas infusions of Rp-cAMPS produced persistent decreases in progressive-ratio responding (Lynch and Taylor, 2005).

Data from the aforementioned studies suggest that PKA activation may be involved in the incentive and motivational aspects of drug addiction, which could contribute to compulsive drug seeking behavior (Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Robbins and Everitt, 1999; Jentsch et al, 2002). It is plausible then that the activation of PKA that we observed in the amygdala during early cocaine abstinence may have multiple consequences. Our data add to this growing literature and suggests that this activation may serve as a molecular substrate for the cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety that occurs during this time period. This conjecture is supported by observation of a concomitant significant increase in amygdalar CRF gene expression during early withdrawal, a result previously described by others (Zhou et al, 2003), but whose mechanism was unknown. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the alterations in cell signaling that we observed during this time period contribute to increased CRF gene expression.

Elevations in CREB phosphorylation have also been observed in the brain after exposure to various stressors, including forced-swim and restraint stress (Kreibich and Blendy, 2005) and are thought to be involved in cocaine-induced drug reinstatement (Kreibich and Blendy, 2004). PKA, pCREB and cAMP-dependent CRE-mediated transcription have also been specifically implicated in alcoholism (Thiele et al, 2000; Pandey et al, 2001; Pandey et al, 2005). Alcohol-preferring rats, which exhibit increased ethanol consumption, express lower levels of CREB and pCREB in the CNA and medial amygdala (MeA), but not in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) compared to non-preferring rats (Pandey et al, 2005). It is thought that these alcohol-preferring rats voluntarily drink excessive amounts of alcohol to reduce high anxiety levels that occur in these animals during this time (Pandey et al, 2005). This concept is further supported by evidence demonstrating that ethanol intake reduced higher anxiety levels in alcohol-preferring rats and also increased CREB function in these animals (Pandey et al, 2005). More recent studies have shown that ethanol withdrawal-induced anxiety in rats is accompanied by decreased CREB phosphorylation, as well as decreased activation of other cell signaling elements, in the CNA and MeA, but not in the BLA (Pandey et al, 2008).

The findings of the aforementioned alcohol studies are contrary to our studies that demonstrate increased expression of anxiety-like behavior in animals during cocaine withdrawal (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006) coincident with increased CREB phosphorylation in the amygdala. However, while the immunofluorescent and electron microscopy experiments were focused largely on evaluating β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in relation to CRF immunoreactivity in the CNA, a limitation of our present study is that the Western blotting and RT-PCR experiments were performed on amygdalar extracts containing the CNA, as well as, other nuclei of the amygdala. Given the cellular alterations that we have observed in the whole amygdala micro-dissections, and the divergent alterations in CREB activation that we have observed compared to previous studies in alcohol addiction, future experiments will be aimed at evaluating potential alterations in CREB activation in the individual amygdalar nuclei. However, we speculate that the cellular changes we observed in the present study are likely a reflection of changes occurring in the CRF-rich CNA specifically since previous studies demonstrate that the CNA is implicated in mediating cocaine withdrawal symptomatology, such as anxiety (Maj et al, 2003; Zhou et al, 2003), and is also associated with mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats (Erb et al, 2001; Leri et al, 2002; McFarland et al, 2004). Nevertheless, chronic cocaine self-administration upregulates norepinephrine transporter in the BLA in animals (Beveridge et al, 2005) and so, it is also plausible that regions such as the BLA underlie the noradrenergic receptor-mediated cellular alterations that we observed. Furthermore, the BLA, thought to be fundamental in the formation and preservation of emotional memories, has been implicated in mediating cue-induced relapse to both major drugs of abuse, such as cocaine (Fuchs and See, 2002; See, 2005) and heroin (Hellemans et al, 2006).

Our findings showing increased CREB phosphorylation during early phases of withdrawal are interesting in light of previous studies that have demonstrated an association between increased pCREB and increased CRF gene activation (Kovacs and Sawchenko, 1996a; Kovacs and Sawchenko, 1996b; Yao et al, 2007). When CREB is phosphorylated, it functions to stimulate transcription in genes that contain the cAMP response element (CRE) in their promoter regions (Siegal et al, 1999; Mayr and Montminy, 2001). It has been established that the CRF gene contains a CRE element in the promoter region and CRF gene transcription is regulated by changes in both cAMP concentration and CRE binding (Seasholtz et al, 1988; Itoi et al, 1996; Hatalski and Baram, 1997). Although indirect, our data suggest a potentially upregulated signaling pathway that may culminate in increased CRF gene transcription leading to the behavioral manifestation of anxiety.

In the present study, we demonstrate that treatment with betaxolol during early cocaine withdrawal reverses the alterations in intracellular messenger expression (PKA regulatory subunit, PKA catalytic subunit and pCREB) that accompany elevations in β1-adrenergic receptors during this time period, as well as returned CRF mRNA levels to that of control animals. Activation of CRF neurotransmission in the amygdala is thought to mediate the anxiety and stress-like symptoms that characterize drug withdrawal syndromes (Sarnyai et al, 1995; Sarnyai, 1998; Koob, 1999; Pollandt et al, 2006). This effect may be mediated by not only local CRF signaling within the amygdala, but also by the activation of CRF projections to other brain regions which mediate anxiety and stress such as, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Koob, 1999; Koob and Heinrichs, 1999; Bourgeais et al, 2001) and the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (Koob and Heinrichs, 1999; Van Bockstaele et al, 1999; Dunn et al, 2004).

The proposed mechanism underlying the efficacy of betaxolol treatment is supported by our anatomical data showing localization of β1-adrenergic receptors to CRF-containing neurons in the amygdala. Our anatomical studies indicate that β1-adrenergic receptors are frequently localized to amygdalar cells containing CRF, in that, more than half of CRF-labeled neurons in the amygdala also express labeling for β1-adrenergic receptor. While our experiments demonstrated that β1-adrenergic receptors were distributed both on the plasma membrane and/or in the cytoplasm of CRF-labeled neurons, we found β1-adrenergic receptors to be primarily localized to the plasma membrane of those neurons. This finding suggests that the majority of β1-adrenergic receptors on CRF neurons may be available for ligand binding, and hence, emphasizes the potential importance of this anatomical substrate in the modulation of CRF gene expression by modulation of β1-adrenergic receptors. Moreover, dendrites of co-localized CRF and β1-adrenergic receptors form both asymmetric and symmetric synapses with axon terminals, an indication that these synapses may be either excitatory or inhibitory in nature. Together, this compelling data further supports the hypothesis that the cellular interactions between β1-adrenergic receptors and CRF in the amygdala may serve as an important circuit involved in the induction of anxiety following cessation of chronic cocaine use.

Studies from our laboratory and others have shown that early cocaine withdrawal in rats is characterized by the behavioral manifestation of anxiety (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006) and also by the augmentation of amygdalar CRF gene expression (Zhou et al, 2003). Our data support that these effects are likely linked to increases in amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptor expression that occurs during this time period. Nonetheless, it has not yet been determined whether treatment with a β1-adrenergic receptor agonist can mimic the effects of cocaine withdrawal, either by the precipitation of anxiety-like behavior or by elevating CRF gene expression. Hence, this type of study may indeed be a fruitful avenue to pursue in order to further elucidate the cellular mechanism underlying the role of β1-adrenergic receptors in cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety.

In conclusion, the findings contained in the present study may have pharmacotherapeutic implications, as blocking amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptors may be a clinically effective means of modulating the activation of CRF neuronal mechanisms that likely prompt negative symptomatology during early phases of drug withdrawal. Betaxolol is an FDA approved drug (brand name: Kerlone) currently used in clinical settings to treat glaucoma (Hardman et al, 2001; Mosby, 2006), hypertension (Mann and Gerber, 2001) and specific coronary dysfunctions (Koh et al, 1995). Betaxolol, is classified as highly selective for β1-adrenegic receptors (Mosby, 2006), readily crosses the blood brain barrier (Swartz, 1998), and has no partial agonist activity (Mosby, 2006). Other β1–adrenergic receptor antagonists such as, metoprolol, atenolol, esmolol, and acebutolol were considered for use in the present study, but were disregarded because these agents either had limited ability to penetrate the brain, had some intrinsic sympathomimetic activity or had a very short duration of action (Hardman et al, 2001).

Propranolol (brand name: Inderal), a non-selective beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist, used to treat hypertension, has demonstrated efficacy in blocking cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety in rats during early abstinence (2 days) from chronic cocaine administration (20 mg/kg/day, 14 days) (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993) and, in clinical studies, has shown some promising effects in individuals with more severe cocaine withdrawal symptoms (Kampman et al, 2001). Our previous studies (Rudoy and Van Bockstaele, 2006) demonstrate that no significant alteration in amygdalar β2-adrenergic receptor expression occurs during cocaine withdrawal in rats, alas, propanolol may not be the most ideal treatment for cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety, as propanolol blocks both β1- and β2- adrenergic receptors. β2-adrenergic receptors, similar to β1-adrenergic receptors, are Gs-protein-coupled receptors and both function to increase cAMP. However, at present, there is no evidence in the literature that these two receptors regulate expression of the exact same genes. More specifically, the present study demonstrates that treatment with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal blocks increases in amygdalar CRF gene expression; an effect that we hypothesize may underlie its efficacy in ameliorating withdrawal-related anxiety. Propanolol may also potentially affect amygdalar CRF gene expression, as it blocks both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors, however, it is unknown at this time if this molecular alteration could underlie the partial efficacy of propanolol in treating cocaine withdrawal symptomatology. It is also conceivable that propanolol has not met with full success in treating cocaine withdrawal symptoms, since propanolol, by unnecessarily blocking β2-adrenergic receptors that have not been altered by the drug withdrawal, could possibly elicit counter-productive effects (e.g. disturb the regulation of other genes). Collectively, the preclinical and clinical studies described above are supportive of the potential pharmacotherapeutic value of betaxolol in the treatment of cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety. However, future studies are warranted to further characterize the biological underpinnings of amygdalar involvement in withdrawal-induced anxiety, as well as examine the effect of direct intracranial β1-adrenergic receptor blockade on amygdalar CRF peptide expression and CRF release in this important limbic region.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Predoctoral Fellowship, NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31DA019311) to C.R. and DA15395 and DA009082 to E.V.B. The authors would like to thank Kristen Smith and Sarah Kidd for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- PKA

cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- pCREB

phosphorylated CREB

- CNA

central nucleus of the amygdala

- PB

phosphate buffer

- TS

tris-saline buffer

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase

- BLA

basolateral nucleus of the amygdala

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

The authors would like to state that no prior, current or pending conflict of interest exists for any of the authors (Carla A. Rudoy, Arith-Ruth S. Reyes and Elisabeth J. Van Bockstaele) pertaining to the research contained in the present manuscript submission. Furthermore, the authors declare that except for income received from their primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science; New York: 2002. Chapter 15: Cell Communication. [Google Scholar]

- Asyyed A, Storm D, Diamond I. Ethanol activates cAMP response element-mediated gene expression in select regions of the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2006;1106:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke JD, Hyman SE. Addiction, dopamine, and the molecular mechanisms of memory. Neuron. 2000;25:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Effects of chronic cocaine self-administration on norepinephrine transporters in the nonhuman primate brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:781–788. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeais L, Gauriau C, Bernard JF. Projections from the nociceptive area of the central nucleus of the amygdala to the forebrain: a PHA-L study in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:229–255. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Gold MS. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor-like peptides in cannabis, nicotine, and alcohol dependence. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:505–528. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Zislis G, Wilson C, Gold MS. Antagonism of CRF receptors prevents the deficit in brain reward function associated with precipitated nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:955–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EC, Williams CL. Adrenergic activation of the nucleus tractus solitarius potentiates amygdala norepinephrine release and enhances retention performance in emotionally arousing and spatial memory tasks. Behav Brain Res. 2000;112:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Swiergiel AH, Palamarchouk V. Brain circuits involved in corticotropin-releasing factor-norepinephrine interactions during stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:25–34. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Salmaso N, Rodaros D, Stewart J. A role for the CRF-containing pathway from central nucleus of the amygdala to bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s002130000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, See RE. Basolateral amygdala inactivation abolishes conditioned stimulus-and heroin-induced reinstatement of extinguished heroin-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:425–433. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0997-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez GA, Menzel P, Leonard J, Fischer WH, Montminy MR. Characterization of motifs which are critical for activity of the cyclic AMP-responsive transcription factor CREB. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1306–1312. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR. Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell. 1989;59:675–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. Axo-somatic and axo-dendritic synapses of the cerebral cortex: an electron microscope study. J Anat. 1959;93:420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Goodman Gilman A, editors. McGraw-Hill. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Beta-adrenergic antagonists attenuate withdrawal anxiety in cocaine- and morphine-dependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02244345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatalski CG, Baram TZ. Stress-induced transcriptional regulation in the developing rat brain involves increased cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-regulatory element binding activity. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:2016–2024. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KG, Everitt BJ, Lee JL. Disrupting reconsolidation of conditioned withdrawal memories in the basolateral amygdala reduces suppression of heroin seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12694–12699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3101-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoi K, Horiba N, Tozawa F, Sakai Y, Sakai K, Abe K, Demura H, Suda T. Major role of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A pathway in corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression in the rat hypothalamus in vivo. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2389–2396. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Olausson P, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR. Stimulation of protein kinase a activity in the rat amygdala enhances reward-related learning. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:111–118. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen M, Delghandi MP, Moens U. What turns CREB on? Cell Signal. 2004;16:1211–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman KM, Volpicelli JR, Mulvaney F, Alterman AI, Cornish J, Gariti P, Cnaan A, Poole S, Muller E, Acosta T, Luce D, O’Brien C. Effectiveness of propranolol for cocaine dependence treatment may depend on cocaine withdrawal symptom severity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KK, Song JH, Kwon KS, Park HB, Baik SH, Park YS, In HH, Moon TH, Park GS, Cho SK, et al. Comparative study of efficacy and safety of low-dose diltiazem or betaxolol in combination with digoxin to control ventricular rate in chronic atrial fibrillation: randomized crossover study. Int J Cardiol. 1995;52:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(95)02480-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Heinrichs SC. A role for corticotropin releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to stressors. Brain Res. 1999;848:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs KJ, Sawchenko PE. Regulation of stress-induced transcriptional changes in the hypothalamic neurosecretory neurons. J Mol Neurosci. 1996a;7:125–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02736792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs KJ, Sawchenko PE. Sequence of stress-induced alterations in indices of synaptic and transcriptional activation in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons. J Neurosci. 1996b;16:262–273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6686–6692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. The role of cAMP response element-binding proteins in mediating stress-induced vulnerability to drug abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2005;65:147–178. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)65006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwintkiewicz J, Cai Z, Stocco C. Follicle-stimulating hormone-induced activation of Gata4 contributes in the up-regulation of Cyp19 expression in rat granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:933–947. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Pickel VM. Electron Microscopic Preembedding Double-Immunostaining Methods. In: Heimer L, Zaborszky L, editors. Neuroanatomical Tract-Tracing Methods. Vol. 2. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. pp. 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5713–5718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Takeda H, Tsuji M, Liu L, Matsumiya T. Antagonism of central CRF systems mediates stress-induced changes in noradrenaline and serotonin turnover in rat brain regions. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1998;20:409–417. doi: 10.1358/mf.1998.20.5.485702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Taylor JR. Persistent changes in motivation to self-administer cocaine following modulation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) activity in the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1214–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Turchan J, Smialowska M, Przewlocka B. Morphine and cocaine influence on CRF biosynthesis in the rat central nucleus of amygdala. Neuropeptides. 2003;37:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann SJ, Gerber LM. Low-dose alpha/beta blockade in the treatment of essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Davidge SB, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Limbic and motor circuitry underlying footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1551–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzaghi F, Rassnick S, Heinrichs S, Baldwin H, Pich EM, Weiss F, Koob GF. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the anxiogenic effects of ethanol withdrawal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;739:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb19819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:807–822. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PA, Ozer J, Salunek M, Jan G, Zerby D, Campbell S, Lieberman PM. A human TATA binding protein-related protein with altered DNA binding specificity inhibits transcription from multiple promoters and activators. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7610–7620. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosby. Mosby’s Drug Consult. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- NIDA. National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. http://www.nida.nih.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Roy A, Mittal N. Effects of chronic ethanol intake and its withdrawal on the expression and phosphorylation of the creb gene transcription factor in rat cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:857–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Zhang H, Roy A, Xu T. Deficits in amygdaloid cAMP-responsive element-binding protein signaling play a role in genetic predisposition to anxiety and alcoholism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2762–2773. doi: 10.1172/JCI24381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Zhang H, Ugale R, Prakash A, Xu T, Misra K. Effector immediate-early gene arc in the amygdala plays a critical role in alcoholism. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2589–2600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4752-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HDF. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System: Neurons and Their Supporting Cells. Oxford University Press, Inc; New York: 1991. Chapter 1: General Morphology of the Neuron; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A. Chapter 2: Connectivity of the rat amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pollandt S, Liu J, Orozco-Cabal L, Grigoriadis DE, Vale WW, Gallagher JP, Shinnick-Gallagher P. Cocaine withdrawal enhances long-term potentiation induced by corticotropin-releasing factor at central amygdala glutamatergic synapses via CRF, NMDA receptors and PKA. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1733–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Katz LC, LaMantia A-S, McNamara JO, Williams SM, editors. Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates, Inc; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Drug addiction: bad habits add up. Nature. 1999;398:567–570. doi: 10.1038/19208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy CA, Van Bockstaele EJ. Betaxolol, a selective beta(1)-adrenergic receptor antagonist, diminishes anxiety-like behavior during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;31:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z. Neurobiology of stress and cocaine addiction. Studies on corticotropin-releasing factor in rats, monkeys, and humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851:371–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z, Biro E, Gardi J, Vecsernyes M, Julesz J, Telegdy G. Brain corticotropin-releasing factor mediates ‘anxiety-like’ behavior induced by cocaine withdrawal in rats. Brain Res. 1995;675:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00043-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z, Shaham Y, Heinrichs SC. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in drug addiction. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:209–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Daly JW. Acummulation of cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate in cerebral cortical slices from rat and mouse: stimulatory effect of alpha- and beta-adrenergic agents and adenosine. J Neurochem. 1973;21:1319–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seasholtz AF, Thompson RC, Douglass JO. Identification of a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive element in the rat corticotropin-releasing hormone gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1988;2:1311–1319. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-12-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE. Neural substrates of cocaine-cue associations that trigger relapse. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Genova LM, Hope BT, Barnhart WJ, Spencer JJ, Nestler EJ. Involvement of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the nucleus accumbens in cocaine self-administration and relapse of cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1848–1859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01848.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD, editors. Basic Neurochemistry, Molecular, Cellular, and Medical Aspects. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz CM. Betaxolol in anxiety disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1998;10:9–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1026146528290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Willis B, Stadler J, Reynolds JG, Bernstein IL, McKnight GS. High ethanol consumption and low sensitivity to ethanol-induced sedation in protein kinase A-mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL, Page ME. The locus coeruleus as a site for integrating corticotropin-releasing factor and noradrenergic mediation of stress responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;697:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Peoples J, Valentino RJ. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Anatomic basis for differential regulation of the rostrolateral peri-locus coeruleus region by limbic afferents. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pickel VM. Ultrastructure of serotonin-immunoreactive terminals in the core and shell of the rat nucleus accumbens: cellular substrates for interactions with catecholamine afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334:603–617. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pieribone VA, Aston-Jones G. Diverse afferents converge on the nucleus paragigantocellularis in the rat ventrolateral medulla: retrograde and anterograde tracing studies. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:561–584. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Ciccocioppo R, Parsons LH, Katner S, Liu X, Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Ben-Shahar O, Angeletti S, Richter RR. Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;937:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Stenzel-Poore M, Denver RJ. Structural and functional conservation of vertebrate corticotropin-releasing factor genes: evidence for a critical role for a conserved cyclic AMP response element. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2518–2531. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Spangler R, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Increased CRH mRNA levels in the rat amygdala during short-term withdrawal from chronic ‘binge’ cocaine. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;114:73–79. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data