Abstract

Objective:

To study drug use pattern in patients of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) and to analyze the cost of different anti-glaucoma medications.

Materials and Methods:

This prospective study was carried in the glaucoma clinic of a tertiary care teaching hospital over a period of 9 months. The data collected for patients with POAG included the patient's demographic details and the drugs prescribed. Data were analyzed for drug use pattern and cost drugs used.

Results:

In a total 180 prescriptions (297 drugs) analyzed, most drugs (83.83%) were prescribed by topical route as eye drops. β blockers (93.88%) were found to be the most frequently prescribed for POAG. Timolol (82.22%) was the most frequently prescribed drug and timolol with acetazolamide (17.22%) was the most commonly prescribed drug combination. Fixed dose combinations constituted 26.66% of prescriptions. β blockers were found to be cheaper than other anti-glaucoma drugs while prostaglandins analogs were the costliest. Instructions about the route, frequency and duration of treatment were present in all prescriptions. However, instructions regarding instillation of eye drops were missing in all prescriptions.

KEY WORDS: β-blockers, cost analysis, drug use study, primary open angle glaucoma

Introduction

Glaucoma, a chronic, progressive, and most often asymptomatic disease, is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide World Health Organization (WHO) but the leading cause of preventable blindness in multiple racial groups. In India, it is the leading cause of treatable non-reversible blindness.[1] Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is defined as a chronic optic neuropathy with characteristic changes in the optic disc and visual field. Risk factors for POAG include older age, black race, family history (first-degree relative), thinner central corneal thickness, myopia, and elevated intraocular pressure (IOP).[2]

In India there are approximately 11.2 million persons aged 40 years and older with glaucoma. POAG is estimated to affect about 6.48 million.[3] With a rapidly growing ageing population; this figure will increase to 16 million by 2020.[4] Worldwide it is estimated that there will be an increase to 79.6 million by 2020. Of these, 74% will have POAG.[5] With the introduction of innovative tools for early diagnosis and newer medications for treatment, diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma has became more complex.[6] The newer glaucoma medications have advantages like increased efficacy, reduced dosing frequency, and improved side effect profile. Studies related to drug utilization in glaucoma reported from India are scarce.[7] There is also a need for comparing the cost of new glaucoma medications with conventional drugs as the higher cost of therapy can affect the compliance to therapy. Hence this study was undertaken to determine the prescribing pattern and carry out a cost analysis of anti glaucoma drugs in out-patient department of a tertiary care specialty teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was carried out in out-patient department of a tertiary care teaching ophthalmology hospital in glaucoma clinic from April 2008 to December 2008 in Ahmedabad. Approval was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee before initiating the study. The data was collected from patients of all age groups, of either gender who were diagnosed with POAG by the ophthalmologist and agreed to give information. The data was recorded in a proforma containing patient's demographic details, provisional/final diagnosis and the complete prescription which included names of prescribed anti-glaucoma drugs, their dose, frequency, duration, and route of administration.

Since many drugs were prescribed by their brand names, the generic names of drugs and generic contents of each formulation were obtained from commercial publications like Indian Drug Review and Advanced Drug Review May-June 2008. Data was analyzed for drug use pattern and cost of medications.

Average cost of glaucoma drugs (eye drops) was determined by first calculating the cost per milliliter of the various brands mentioned in the Indian Drug Review, May-June, 2008. The size of drop varies between 25 and 50 μl, so on an average 27 drops constitute 1 ml.[8] Assuming use in both eyes for each medication and number of drops required per day (determined using the manufacturer's recommended daily dose regimen), the cost of therapy for 1 month was calculated.

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel version 2007. All parameters were expressed in percentage. Chi-square test was used to analyze the data where appropriate and values with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 180 patients, 100(55.56%) were male and 80 (44.44%) were female. They were classified into three age groups i.e., less than 40, between 40 and 60, and more than 60. Maximum patients 107 (59.44%) were in age group between 40 and 60 years. In this age group 60 were female and 47 were male, the difference being statistically significant (P < 0.01).

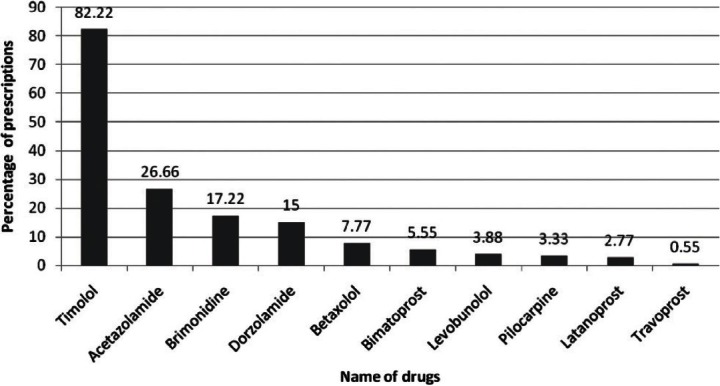

Out of total 297 drugs prescribed, most (83.83%) were prescribed as eye drops. Acetazolamide (16.16%) was the only drug prescribed by oral route. Timolol was found to be the most frequently prescribed drug constituting 82.22% of total prescriptions. Pilocarpine (3.33%), latanoprost (2.77%), and travoprost (0.05%) were the least prescribed drugs [Figure 1]. β-blockers (93.88%) were the most frequently prescribed drug group. Other groups included oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (26.66%), topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (15%), α-2 adrenoceptor agonists (17.22%), prostaglandin analogs (PGA; 8.88%) and cholinergics (3.33%).

Figure 1.

Prescribing frequency of antiglaucoma drugs (n = 180) in a tertiary care hospital

Eighty four prescriptions were prescribed as monotherapy for POAG, timolol (32.22%) being the most frequently prescribed drug. Other single drug prescriptions were brimonidine (5.55%), betaxolol (4.44%), levobunolol (3.33%), latanoprost (0.55%) and pilocarpine (0.55%).

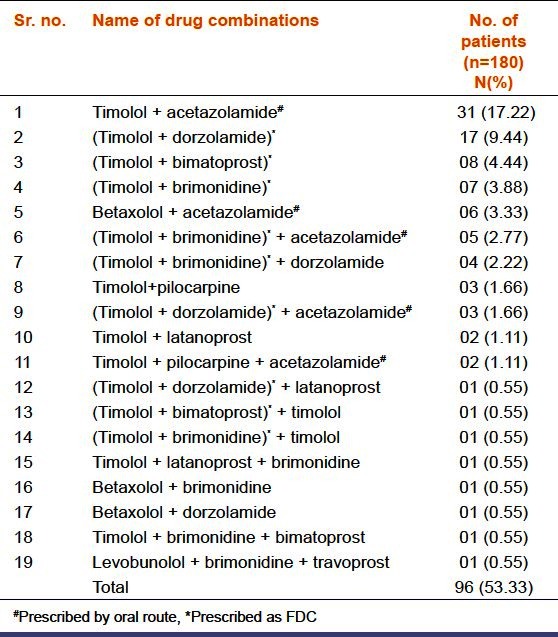

Combination therapy was prescribed to 96 patients including concurrent and fixed dose combinations (FDCs). Timolol and acetazolamide (17.22%) was most commonly prescribed drug combination followed by timolol and dorzolamide (9.44%). Out of 96 prescriptions, 20 contained three drugs, the most common triple combination being timolol+brimonidine+acetazolamide (2.77%). Out of 180 prescriptions, 48 (26.66%) received FDCs. Timolol+dorzolamide (11.66%) being the most commonly prescribed FDC [Table 1].

Table 1.

Combination therapies (concurrent and FDCs) used in primary open-angle glaucoma in a tertiary care hospital

Written instructions to the patients regarding dose, dosing interval and duration of therapy were mentioned in all the prescriptions, but the appointment method of eye drops instillation was not mentioned in any prescription.

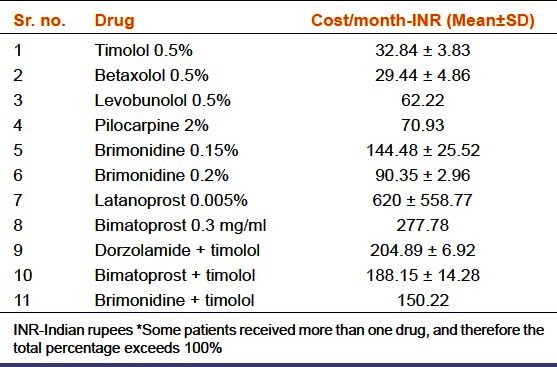

β-blockers were found to be the cheapest of all anti-glaucoma drugs with lowest price for betaxolol and timolol. PGAs were found to be the most expensive among various drug groups available [Table 2].

Table 2.

Average cost of various antiglaucoma drugs prescribed in a tertiary care hospital

Discussion

In this study of total 180 patients, POAG was found to be most prevalent in age group 40-60 years and more prevalent in females than males. These findings are consistent with those reported from India.[3] Most of the drugs were prescribed topically (83.83%) as ophthalmic drops, only acetazolamide being the oral medication (16.16%). Similar results were reported in a study conducted in India earlier.[7] Topical administration of drugs for eye disease minimizes their side effects.[9]

β-blockers were the most frequently prescribed drugs with timolol being the most frequently prescribed drug (82.22%) being higher than earlier study from India (55%).[7] This may be because timolol is also prescribed with other drugs concomitantly or as a fixed dose combination. Since the introduction of β-blockers in the treatment of glaucoma, they are the most frequently prescribed drug groups.[8] Betaxolol and levobunolol were used less because of higher cost. This pattern is in accordance with studies from India.[7] The α-2 receptor agonist brimonidine was the next most commonly prescribed drug which is in accordance with study from Jammu.[7] In our study pilocarpine, a cholinergic drug was prescribed as adjuvant to timolol in 3.33% of prescriptions, much less than reported in earlier study showing decreasing trend of its use.[7]

PGAs formed 8.88% of prescriptions, higher than the earlier Indian study (1%),[7] with bimatoprost being the most commonly prescribed drug suggesting increasing trend of use of PGAs. PGAs have been found to be superior in efficacy to all other topical classes of glaucoma medications.[10] However, a study reporting trends in Australia and New Zealand in 2006 has shown that although PGAs were the first choice drugs, New Zealand ophthalmologists favored β-blockers because of cost, government restrictions and familiarity.[11] Acetazolamide was prescribed in 26.66% of prescriptions which is higher than reported earlier studies for POAG.[7] It is a routine practice in this hospital to prescribe it for a week and then discontinue and replace it with other topical drug if necessary. The rationale given by prescribers was lower cost and faster reduction of IOP. It is used for short period of time so that chance of acidosis and other side effects like bone marrow depression and renal stone could be minimized.

By prescribing combination therapy, ophthalmologists intend to achieve higher reduction in the IOP by all the possible mechanisms which is not obtained by monotherapy.[12] Topical timolol and oral acetazolamide were prescribed concurrently in 17.22% of patients. Timolol+ dorzolamide FDC as topical eye drops is at second place in contrast to earlier study from India which did not report use of this combination in any patient.[7] This combination significantly improves retinal hemodynamics in POAG.[13] The topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have been shown to be beneficial adjuncts to PGAs both during the day and night.[10] However, only one prescription contained this combination because of higher cost.

FDC were prescribed in 26.66% of total prescriptions. In Jammu study, no FDC was prescribed as only one FDC - timolol 0.5% and pilocarpine 2% was available.[7] This study shows rising trend of use of FDC as more rational FDCs are available. Timolol+dorzolamide FDC was the most commonly prescribed FDC. It is more convenient (both easier and faster) to instill 1 drop of a fixed combination than 2 drops from separate bottles of the component medications.[14] So, FDCs if rational, offer benefits of convenience, cost and safety.

In this study, written instructions regarding dose, dosing interval and duration of therapy were mentioned in all the prescriptions which is higher than that reported in earlier study of drug use pattern in ophthalmology from India.[15] However, proper method for instillation was not mentioned in any of the prescription. Patients usually have the habit of applying 2-3 drops in the eye resulting into the wastage, increased cost and poor compliance.[16] The instructions regarding drug instillation is important aspect of ocular therapy.[17]

The cost of betaxolol and timolol was found to be the lowest. In this study, ophthalmologists favored β-blockers because most of the patients attending the out-patient department belong to lower socioeconomic class. These results are in accordance with earlier study from India.[7] The cost of FDC was in between cost of β-blockers and cost of PGAs. Hence FDCs are commonly used because of their cost-effectiveness. In a pharmacoeconomic study, PGAs were found to be costliest and among PGAs, bimatoprost was found to be most economical.[18] Studies conducted in Australia and Japan have shown PGAs as first-line drug for POAG.[11,19] The observed difference in choice of drugs is because of socioeconomic differences between the countries.

Conclusions

To conclude, β-blockers were first line drugs as monotherapy for POAG, timolol being the first choice as it is cost-effective. Timolol and a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor was the most frequently prescribed combination. However, these findings cannot be generalized as prescribing preferences show regional differences. For glaucoma whatever therapy is chosen, the concept to be kept in mind is that glaucoma therapy is lifelong and needs consideration of cost-effectiveness and convenience in individual patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Robin A, Grover DS. Compliance and adherence in glaucoma management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:S93–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.73693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan Y, Varma R. Natural history of glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:S19–23. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.73682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George R, Ve RS, Vijaya L. Glaucoma in India: Estimate burden of disease. J Glaucoma. 2010;19:391–7. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181c4ac5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George R, Vijaya L. First world glaucoma day, March 6, 2008: Tackling challenges in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:97–8. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.39111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh RS, Parikh SR, Navin S, Arun E, Thomas R. Practical approach to medical management of glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:223–30. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.40362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma R, Khajuria R, Sharma P, Sadhotra P, Kapoor B, Kohli K, et al. Glaucoma therapy: Prescribing pattern and cost analysis. JK Science. 2004;6:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephen CG, Mark J, Alan LR, Gail FS. Clinical pharmacology of adrenergic drugs. In: Ritch R, Bruce MS, Theodore K, editors. The Glaucomas, Glaucoma therapy. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book, Inc; 1996. pp. 1425–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehru M, Kohli K, Kapoor B, Sadhotra P, Chopra V, Sharma R. Drug utilization study in outpatient ophthalmology department of Government Medical College. JK Science. 2005;7:149–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh K, Shrivastava A. Medical management of glaucoma: Principles and practice. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:S88–92. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.73691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll SC, Gaskin BJ, Goldberg I, Danesh-Meyer HV. Glaucoma prescribing trends in Australia and New Zealand. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:213–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulkarni SV, Damji KF, Buys YM. Medical management of primary open angle glaucoma: Best practices associated with enhanced patient compliance and persistency. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2008;2:303–14. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costagliola C, Campa C, Parmeggiani F, Incorvaia C, Perri P, D’Angelo S, et al. Effect of 2% dorzolamide on retinal blood flow: A study on juvenile primary open-angle glaucoma patients already receiving 0.5% timolol. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:376–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higginbotham EJ. Considerations in glaucoma therapy: fixed combinations versus their component medications. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas NR, Jindal S, Siddiquei MM, Maini R. Pattern of prescription and drug use in ophthalmology in a tertiary hospital in Delhi. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51:267–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam CS, Bhanwra S, Goel NK, Gupta KS, Sood S. Instillation of drugs in the eye: Importance of proper instructions to the patients. Indian J Pharmacol. 2001;33:386. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flach AJ. The importance of eyelid closure and nasolacrimal occlusion following the ocular instillation of topical glaucoma medications, and the need for the universal inclusion of one of these techniques in all patient treatments and clinical studies. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:138–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frenkel RE, Frenkel M, Toler A. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of prostaglandin and prostamide therapy for patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. BMC Ophthalmol. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashiwagi K. Changes in trend of newly prescribed anti-glaucoma medications in recent nine years in a Japanese local community. Open Ophthalmol J. 2010;4:7–11. doi: 10.2174/1874364101004010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]