Abstract

Clofazimine-induced crystal-storing histiocytosis is a rare but well-recognized condition reported in literature. In addition to common reddish discoloration of the skin, clofazimine produces gastrointestinal disorder, sometimes severe abdominal pain. Also, the pathologic and radiologic findings can produce diagnostic difficulties if the pathological changes caused by it are not known. The authors report a case in a patient of leprosy to emphasize the importance of history, radiologic, and pathologic findings in small intestine. Clofazimine crystals are red in the frozen section and display bright-red birefringence. With the knowledge of this rare condition caused by clofazimine, appropriate management to avoid an unnecessary laparotomy is possible.

KEY WORDS: Clofazimine, leprosy, multi drug therapy

Introduction

Clofazimine is now an established component of multi-drug treatment (MDT) for leprosy. It causes reddish discoloration of the skin as well as ichthyosis.[1] The first report of gastrointestinal toxicity of this drug was published by Atkinson et al.,in 1967. It was a case of a 19-year-old male treated for leprosy by clofazimine at a dose of 600 mg per day. The patient experienced epigastric distress with occasional vomiting unrelated to meals, intermittent abdominal pain, mal-absorption, and rebound tenderness.[2] The radiological abnormalities revealed coarsening of the mucosal pattern and segmentation of barium in the ileum and distal jejunum. Biopsy of jejunum demonstrated red crystals in the lamina propria accompanied by a moderate number of plasma cells. After the discontinuation of the drug, marked improvement was observed. So far, similar cases confirmed by histological findings of clofazimine crystals and/or radiological abnormalities have been reported.[3–5] These reports emphasized the importance of recognizing this condition to avoid misdiagnosed laparotomy. In this report, we present the case of clofazimine-induced enteropathy in a leprosy patient with a probable association with the drug as per the World Health Organization (WHO) causality assessment scale and Naranjo's causality assessment scale.

Case Report

A 19-year-old tribal male patient was diagnosed with multibacillary leprosy, for which he was taking MDT for the last 8 months. He was under regular follow-up in the Department of Dermatology at Government Medical College, Jagdalpur, Chhattisgarh. He presented with 1 week history of abdominal pain which was described as periumbilical, dull-aching pain without any referred pain. The pain was recently aggravating, dull-aching, intermittent, lasting for hours, tended to occur during the night, not related to food intake and was not relieved by prescribing a proton pump inhibitor or antacid.

Patient was then referred to surgical unit, where physical findings revealed few enlarged lymph nodes at the left cervical region and mild tenderness at the umbilical region without guarding or stiffness. No hepatosplenomegaly or enlargements of the superficial nerve were detected. Abnormal laboratory findings included eosinophilia, hypoalbuminemia, and mild hyperglobulinemia. The serology test for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and syphilis were negative.

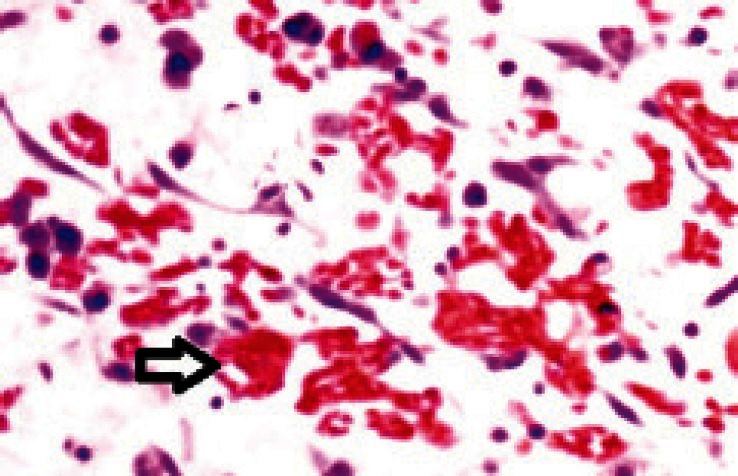

To exclude peptic ulcer disease, urease test and microscopic examination of gastric mucosa was done. The lymph node biopsy failed to demonstrate malignant lymphoma. Endoscopic biopsies of the stomach, duodenum, as well as jejunum were performed. Mild, chronic inflammation of the gastric and duodenal mucosa was observed. Few crystal-storing (red colored) histiocyte was detected in the lamina propria of the duodenum, but several crystal-storing histiocyte were observed in the lamina propria of the jejunum [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Several crystal-storing histiocytes (arrows) were observed in the lamina propria of the jejunum

The patient's illness history revealed that he had lepra-2 reaction [Erythema NodosumLeprosum (ENL)] during MDT course for which he was prescribed clofazimine in high dose; that is 100 mg thrice a day for 1 month; later 100 mg twice a day for next 15 days with additional appropriate corticosteroid and then regular MDT treatment was continued. The reaction subsided without any adverse events at that time.

After a brief text search, it was concluded that these crystals represented clofazimine crystals, and the afore mentioned clinical, radiographic, and pathologic descriptions were characteristic of clofazimineenteropathy.[2–4]

All clinical and lab data indicated that clofazimine was the reason for sudden onset of pain abdomen. The offending drug was stopped with appropriate alternative regimens. The patient improved slowly over about 2 months of follow-up. He still had intermittent abdominal pain that was relieved by analgesics.

Discussion

In the dose employed for MDT clofazimine is well tolerated, but enteritis commonly occurs with higher doses used to treat lepra reaction. This case history and other relevant data revealed that patient had taken clofazimine in high dose for the treatment of lepra reaction.

On brief literature search it was found that clofazimine caninduce three types of enteropathy: Eosinophilic/allergic pattern, a Crohn's disease-like pattern with granulomas and clofazimine-induced crystal-storing histiocytois.[6]

In the present case, patient was receiving clofazimine, dapsone, and rifampicin. Both dapsone and rifampicin do not have an obvious association with enteropathy. According to Hartwig scale, the case was categorized as severe and preventability of the case was probable as per modified Schumock and Thorton scale. The causality assessment of clofazimine-induced enteropathy with clofazimine using Naranjo's Causality Assessment Scale showed a score of 7. WHO Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) Causality Assessment Criteria also indicated a probable association.[7,8]

In summary, this is an unusual case of clofazimineenteropathy presenting as “clofazimine-induced crystal storing histiocytosis” based on the unique pathologic findings. This drug is useful not only in the treatment of leprosy and some dermatologic disorders, but also in treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex infection in patients with HIV infection.[9] Prescribers should be aware of this adverse effect of clofazimine to provide appropriate patient management, to avoid unnecessary exploratory laparotomy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.William AP. Chemotherapy of tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complex disease, and leprosy. In: Laurence LB, John SL, Parker KL, editors. Goodman Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2006. pp. 1219–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson AJ, Jr, Sheagren JN, Rubio JB, Knight V. Evaluation of B.663 in human leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1967;35:119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belaube P, Devaux J, Pizzi M, Boutboul R, Privat Y. Small bowel deposition of crystals associated with the use of clofazimine (Lamprene) in the treatment of prurigonodularis. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1983;51:328–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryceson A. Unnecessary laparotomy for abdominal pain and fever due to clofazimine. Lepr Rev. 1979;50:258–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong PY, Ti TK. Severe abdominal pain in low dosage clofazimine. Pathology. 1993;25:24–6. doi: 10.3109/00313029309068897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geboes K, De Hertogh G, Ectors N. Drug-induced pathology in the large intestine. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2006;12:239–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uppsala: The Uppsala Monitoring Centre; [Last accessed on 2012 Feb 5]. The use of WHO-UMC system for standardized case causality assessment (monograph on the Internet) Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/graphics/4409.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masur H. Recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy for disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Public Health Service Task Force on Prophylaxis and Therapy for Mycobacterium avium Complex. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:898–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309163291228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]