Abstract

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) or mitochondrial complex II is a multimeric enzyme that is bound to the inner membrane of mitochondria and has a dual role as it serves both as a critical step of the tricarboxylic acid or Krebs cycle and as a member of the respiratory chain that transfers electrons directly to the ubiquinone pool. Mutations in SDH subunits have been implicated in the formation of familial paragangliomas (PGLs) and/or pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) and in Carney–Stratakis syndrome. More recently, SDH defects were associated with predisposition to a Cowden disease phenotype, renal, and thyroid cancer. We recently described a kindred with the coexistence of familial PGLs and an aggressive GH-secreting pituitary adenoma, harboring an SDHD mutation. The pituitary tumor showed loss of heterozygosity at the SDHD locus, indicating the possibility that SDHD’s loss was causatively linked to the development of the neoplasm. In total, 29 cases of pituitary adenomas presenting in association with PHEOs and/or extra-adrenal PGLs have been reported in the literature since 1952. Although a number of other genetic defects are possible in these cases, we speculate that the association of PHEOs and/or PGLs with pituitary tumors is a new syndromic association and a novel phenotype for SDH defects.

Introduction

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) or succinate-coenzyme Q reductase is a multimeric enzyme that is bound to the inner membrane of mitochondria (Oyedotun & Lemire 2004). It has a dual role as it serves both as a critical step of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) or Krebs cycle and as a member of oxidative phosphorylation, the respiratory chain that transfers electrons directly to the ubiquinone pool (Kantorovich & Pacak 2010). It is a highly conserved protein complex that consists of four subunits: two hydrophilic, a flavoprotein (SDHA) and an iron–sulfur protein (SDHB) that together form the catalytic core of the enzyme (SDHA serves as the substrate binding site for succinate), and two hydrophobic subunits, SDHC and SDHD, that anchor the holotetramer to the membrane and serve as the ubiquinone site (Oyedotun & Lemire 2004, Kantorovich & Pacak 2010).

Syndromes related to SDHx mutations

The discovery that mutations in genes coding for the subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD were responsible for the formation of multiple and possibly coexisting parasympathetic and sympathetic paragangliomas (PGLs) and/or pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) (Baysal et al. 2000, Astuti et al. 2001) made obsolete (Dluhy 2002) at least one part of the axiom that had been proposed by Bravo & Gifford (1984); the so-called ‘10 rule’ had stated that 10% of PHEOs were bilateral, 10% malignant, 10% normotensive, 10% extra-adrenal, and 10% genetic origin. Today, we know that as many as 40% of PHEOs/PGLs may be due to a genetic defect (Raygada et al. 2011); in children and young adults, this may be true in as many as three out of four patients.

In 2007, Stratakis et al. described germline mutations of the SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD genes in patients with PGLs and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), negative for mutations in PDGFRA or KIT genes (McWhinney et al. 2007). GISTs from these patients showed allelic losses of the SDHB and SDHC chromosomal loci pointing to a tumor-suppressor function of SDH subunits (SDHx) in these neoplasms. This was the first time that a germline mitochondrial oxidation defect was linked to predisposition for development of a sarcoma. More recently, SDHx mutations (or functional variants) were associated with predisposition to a Cowden disease-like phenotype that consisted of breast, endometrial, thyroid, kidney, colorectal cancers, dermatological features such as oral and skin papillomas, and neurological manifestations such as autism and Lhermitte Duclos disease (Ni et al. 2008), as well as with renal and thyroid cancer (Neumann et al. 2004, Vanharanta et al. 2004).

Pituitary adenomas and PHEOs/PGLs as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes

Pituitary adenomas represent one of the components of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) due to mutations in MEN1 gene, the other components being primary hyperparathyroidism and pancreatic tumors. Adenomas and adenomatous hyperplasia of the thyroid and adrenal glands may also occur in patients with MEN1 (Thakker 2010).

PHEOs/PGLs, primary hyperparathyroidism, and medullary thyroid cancer are the main tumors that occur in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), with particular marfanoid habitus in MEN2B subtype. The genetic causes are gain-of-function mutations in RET proto-oncogene (Wohllk et al. 2010).

There have been some reports in the literature of MEN1 where PHEOs (unilaterally or bilaterally) were identified in patients with proven MEN1 mutations. However, the prevalence of PHEOs in MEN1 appears to be < 0.1% (Gatta-Cherifi et al. 2012).

We just described a kindred with the coexistence of familial PGLs and an aggressive GH-secreting pituitary adenoma, harboring a SDHD mutation (Xekouki et al. 2012). The pituitary tumor showed loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the SDHD locus, indicating the possibility that this gene’s loss was causatively linked to the development of the neoplasm (Xekouki et al. 2012). Until this report, coexistence of a pituitary adenoma and PHEOs/PGL was not recognized as a distinct entity. However, since 1952, we have identified 29 cases in the literature of pituitary adenomas copresenting with PHEO and/or extra-adrenal PGLs (Table 1); in most reports, the coexistence of these two tumors was described as a unexpected ‘coincidence’. Unfortunately, no genetic testing was available until the 1990’s, so we can only hypothesize that some of the early cases presented in Table 1 could represent cases of MEN syndromes or may be due to SDHx mutations. The most recent cases described by Sisson et al. (2011) and Zhang et al. (2011) have a lot of similarities with our case and most probably are cases of familial PGLs.

Table 1.

Reported cases of coexistence of PHEO/PGL and pituitary adenoma

| Report | Agea/sex | Case | Genetic screening | Family history for endocrine tumors | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iversen (1952) | 44/M | Acromegaly/PHEO | –b | NA | |

| Kahn & Mullon (1964) | 40/M | Acromegaly/PHEO | –b | NA | |

| O’Higgins et al. (1967) | 21/F | Acromegaly/PHEO increased serum calcium (PHP?) | –b | NA | |

| Steiner et al. (1968) | 41/M | Cushing’s disease/bilateral PHEOs/medullary thyroid cancer | –b | Positive for MEN for VI generations | |

| Wolf et al. (1972) | 43/F | Pituitary adenoma (probably nonfunctioning), PHEO/PHP, medullary thyroid cancer | –b | NA | |

| Farhi et al. (1976) | 19/F | Acromegaly/PGLs/, parathyroid hyperplasia, pigmentary abnormalities | –b | Negative | |

| Kadowaki et al. (1976) | 44/M | Acromegaly/PHEO | –b | NA | |

| Osamura et al. (1977) | 58/M | Acromegaly/PHEO/renal carcinoma | –b | NA | |

| Manger et al. (1977) | 15/F | Acromegaly/PHEO | –b | NA | |

| Melicow (1977) | 52/F | Chromophobe adenoma of pituitary/papillary carcinoma of thyroid/PHEO diagnosed postmortem | –b | NA | |

| Janson et al. (1978) | 28/F | Pituitary adenoma (probably nonfunctioning) /bilateral PHEO | –b | Positive for PHEOs/ islet cell tumor/ renal adenoma | |

| Alberts et al. (1980) | 36/F | Pituitary adenoma (?)/PHEO/islet cell tumor (gastrinoma), Cushing’s syndrome (adrenal cortical adenoma), parathyroid hyperplasia | –b | NA | |

| Myers & Eversman (1981) | 53/F | Acromegaly/PHEO/PHP | –b | Negative | |

| Anderson et al. (1981) | 53/F | Acromegaly/PHEO/ parathyroid hyperplasia (diagnosed post-mortem) | –b | Negative | |

| Anderson et al. (1981) | 58/F | Acromegaly/PHEO | –b | Negative | Hypertension in one sibling (PHEO?) |

| Meyers (1982) | 35/F | Prolactinoma/PHEO | –b | NA | |

| Roth et al. (1986) | 43/M | Acromegaly (nodular somatotroph hyperplasia)/PHEO | –b | Negative | Ectopic GHRH secretion from PHEO |

| Bertrand et al. (1987) | 26/M | Prolactinoma/PHEO/bilateral medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), parathyroid adenoma | –b | Father: metastatic MTC/probably PHEO | |

| Teh et al. (1996) | 41/M | Acromegaly/PHEO/abdominal PGL | RET: (−) | NA | |

| Baughan et al. (2001) | 43/M | Acromegaly/PHEO/hemangioma/lipoma/parotid adenoma | RET: (−) | Negative | Maybe ectopic GHRH secretion (not measured) |

| Dünser et al. (2002) | 56/M | Pituitary adenoma (probably not secreting) /PHEO | Not performed | NA | |

| Sleilati et al. (2002) | 57/F | Acromegaly/PHEO | RET: negative | Negative | Negative for GHRH ectopic secretion |

| Breckenridge et al. (2003) | 59/M | Pituitary adenoma (non- secreting)/PHEO | Not performed | Negative | |

| López-Jiménez et al. (2008) | 60/M | Prolactinoma/nonsecreting PGL | SDHC (+) | 2/4 children are carriers of the same mutation. Parents’ history: negative | |

| Saito et al. (2010) | 40/M | Acromegaly/MTC | RET (+) | Mother PHEO/MTC RET (+) | |

| Zhang et al. (2011) | 45/M | Acromegaly/PGLs | Not performed | Father and sister neck PGLs | |

| Heinlen et al. (2011) | 60/M | PHEO/nonsecreting pituitary adenoma/MTC | RET (+) | NA | |

| Sisson et al. (2011) | 29/M | Bilateral PHEOs/ acromegaly/PTC | Not performed | Negative | |

| Xekouki et al. (2012) | 37/M | Acromegaly/bilateral PHEOS/PGLs | SDHD (+) LOH of SDHD locus in pituitary adenoma | Sister, paternal uncle: neck PGLs (same mutation) |

NA, not available; PHEO, pheochromocytoma; PGL, paraganglioma; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; MTC, medullary thyroid cancer; PHP, primary hyperparathyroidism; MEN, multiple endocrine neoplasia; M, male; F, female.

The age at first visit.

DNA testing was not available at that time.

The only other reported patient with a pituitary tumor and neck PGLs due to an SDHC splice site mutation is the one reported by López-Jiménez et al. (2008). However, the prolactinoma could not be tested for LOH, so we can only speculate that this particular mutation may have contributed to the patient’s pituitary tumor formation.

Proposed mechanisms

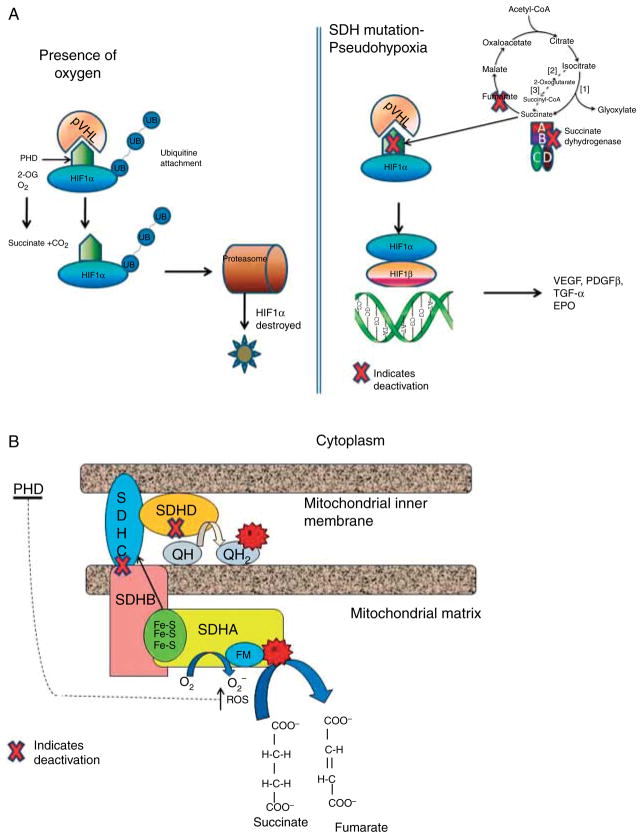

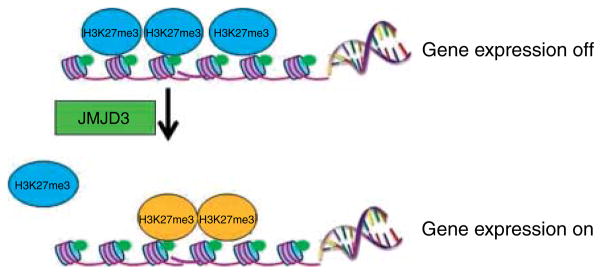

The above data and the number of cases in Table 1 indicate that the association of certain pituitary tumors and SDHx mutations may be a real one, adding this neoplasm to the ever increasing list of lesions associated with SDH deficiency. How could this be molecularly plausible? Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how the dysfunction of SDHx can lead to the formation of PHEOs/PGLs. The first model is ‘pseudohypoxia’ and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In normoxic conditions, a family of oxygen-dependent enzymes known as prolyl hydroxylases (PHD) 1, 2, and 3 (also known as Egln2, Egln1, and Egln3) hydroxylate the three α subunits of hypoxia inducible factor α (HIF1α, HIF2α, and HIF3α). The hydroxylated HIFαs are then targeted by von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) protein, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, polyubiquitinated and degraded in the proteasome. Only hydroxylated HIFαs can be targeted by VHL for degradation. However, if PHDs are inhibited by the accumulated succinate (such as when SDHx are mutated), HIFαs are not hydroxylated, escape degradation, and translocate to the nucleus, where they dimerise with HIF1β and bind to specific promoter elements of target genes including critical angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, and cell survival, and possibly a number of others (Raimundo et al. 2011; Fig. 1a). Activation of the HIF pathway and the resulting angiogenic and glycolytic response in SDHx-mutated tumors was first reported by Selak et al. (2005) and has been replicated in many studies. Certainly, the ‘pseudohypoxia’ hypothesis is not new: Otto Warburg in the 1920s described a striking rate of glycolysis and lactate production in tumor cells, in the presence of normal oxygen concentrations (Warburg 1956). Warburg proposed that this phenomenon might be related to a defect in mitochondrial respiration, or some other mechanism that allows the tumor cell to function as hypoxic under normoxic conditions. It took over 80 years for the ‘Warburg effect’ to be confirmed, and today, it is the basis for the use of functional imaging strategies such as the [18F]deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) for the diagnosis of PHEO/PGLs (Bayley & Devilee 2010). The generation of ROS due to the SDH/complex II deficiency in the presence of SDHx mutations has also been implicated in tumor formation, although ROS are usually a ‘by-product’ of other elements of the electron transport chain, particularly complex I (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and III (ubiquinone-cytochrome c oxidoreductase). ROS might promote tumor formation in SDH-deficient cells by inhibiting PHD activity similar to succinate accumulation (Bardella et al. 2011; Fig. 1b). The accumulation of succinate in SDH-deficient tumors may also inhibit other components of α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes besides PHDs. It was recently demonstrated that loss of SDHB subunit in a yeast model led to succinate accumulation, which could cause the inhibition of two different α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases: the Jlp1, involved in sulfur metabolism, and the histone demethylases Jhd1, which belongs to the JmjC-domain-containing histone demethylase (JHDM) enzymes. It was also demonstrated that JMJD2D, the corresponding human JHDM, was inhibited by succinate accumulation (Smith et al. 2007). Inhibition of the histone demethylases could certainly lead to tumor formation by a variety of epigenetic changes (Bardella et al. 2011). Indeed, increased methylation of histone H3 that can be reversed by overexpression of the JMJD3 histone demethylase was recently reported in SDHB-silenced cells (Fig. 2). ChIP analysis revealed that the core promoter of IGFBP7, which encodes a secreted protein upregulated after the loss of SDHB, showed decreased occupancy by trimethylated lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) in the absence of SDHB. Moreover, type I chief cells, which are considered the neoplastic component of PGLs, were shown as the major methylated histone-immunoreactive component of the paraganglial carotid tumors tested (Cervera et al. 2009). Overall, these findings demonstrated that succinate could act not only as a messenger between mitochondria to cytosol but also as a signal between mitochondria to nucleus, for the regulation of chromatin structure and gene expression.

Figure 1.

(a) Mechanisms of pseudohypoxia in inherited PHEO and/or PGLs: inactivation of SDH leads to the abnormal stabilization of HIFs in normoxia that escape degradation and translocate to the nucleus, where they dimerise with HIF1β and promote transcription of genes that enhance tumorigenesis, e.g. VEGF, PDGF-β (2-OG, a-ketoglutarate; HIFs, hypoxia-inducible factors; PHD, prolyl hydroxylases; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; VHL, Von Hippel–Lindau). (b) Oxidation of succinate to fumarate transfers the electrons through a sequence of steps from the flavin moiety in SdhA to a set of three iron–sulfur clusters in SdhB, to the ubiquinone binding site in SdhC and SdhD. When complex II is disrupted due to mutations in SdhB, SdhC, or SdhD, the electron transfer is impaired promoting superoxide generation through the autoxidation of the reduced flavin group by O2 in the matrix (FM, flavin moiety; Fe-S, iron–sulfur clusters; e−, electron transfer; QH, ubiquinone; QH2, ubiquinol).

Figure 2.

Methylation of histones like trimethylated lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) controls transcription by allowing chromosomal regions to alternate between ‘on’ and ‘off’. Jumonji domain-containing 3 (JMJD3) belongs to a family of enzymes that uses a Jumonji C (JmjC) domain to catalyze demethylation on lysines. In cells with inactivated SDHB, increased methylation of histone H3 can be reversed by overexpression of the JMJD3, indicating that histone demethylases may be involved in the formation of paragangliomas (and related tumors).

Conclusions

Could all of this be happening in the pituitary as well? The mechanism by which SDHx germline mutations might contribute to pituitary tumor formation is still elusive. In our studies, we showed increased expression of HIF1α in the SDHD-mutant tumor cells compared with normal pituitary and GH-secreting adenoma cells without SDH defects (Xekouki et al. 2012). Clearly, further research is needed to prove SDHx mutation involvement in predisposition to pituitary tumors; however, the clinical cases and the preliminary laboratory data make this enzyme a likely candidate for yet another molecular mechanism through which pituitary tumors may form.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was entirely supported by the Intramural Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the review reported.

References

- Alberts WM, McMeekin JO, George JM. Mixed multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1980;244:1236–1237. doi: 10.1001/jama.1980.03310110046029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Lufkin EG, Sizemore GW, Carney JA, Sheps SG, Silliman YE. Acromegaly and pituitary adenoma with phaeochromocytoma: a variant of multiple endocrine neoplasia. Clinical Endocrinology. 1981;14:605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1981.tb02971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, Dahia PL, Douglas F, George E, Sköldberg F, Husebye ES, Eng C, Maher ER. Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;69:49–54. doi: 10.1086/321282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardella C, Pollard PJ, Tomlinson I. SDH mutations in cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2011;1807:1432–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughan J, de Gara C, Morrish D. A rare association between acromegaly and pheochromocytoma. American Journal of Surgery. 2001;182:185–187. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00678-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley JP, Devilee P. Warburg tumours and the mechanisms of mitochondrial tumour suppressor genes. Barking up the right tree? Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2010;20:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Myssiorek D, Bosch A, van der Mey A, Taschner PE, Rubinstein WS, Myers EN, et al. Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science. 2000;287:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JH, Ritz P, Reznik Y, Grollier G, Potier JC, Evrad C, Mahoudeau JA. Sipple’s syndrome associated with a large prolactinoma. Clinical Endocrinology. 1987;27:607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1987.tb01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo EL, Gifford RW., Jr Current concepts. Pheochromocytoma: diagnosis, localization and management. New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311:1298–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198411153112007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge SM, Hamrahian AH, Faiman C, Suh J, Prayson R, Mayberg M. Coexistence of a pituitary macroadenoma and pheochromocytoma – a case report and review of the literature. Pituitary. 2003;6:221–225. doi: 10.1023/B:PITU.0000023429.89644.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera AM, Bayley JP, Devilee P, McCreath KJ. Inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase dysregulates histone modification in mammalian cells. Molecular Cancer. 2009;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dluhy RG. Pheochromocytoma – death of an axiom. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:1486–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205093461911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dünser MW, Mayr AJ, Gasser R, Rieger M, Friesenecker B, Hasibeder WR. Cardiac failure and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in a patient with endocrine adenomatosis. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2002;46:1161–1164. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhi F, Dikman SH, Lawson W, Cobin RH, Zak FG. Paragangliomatosis associated with multiple endocrine adenomas. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 1976;100:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta-Cherifi B, Chabre O, Murat A, Niccoli P, Cardot-Bauters C, Rohmer V, Young J, Delemer B, Du Boullay H, Verger MF, et al. Adrenal involvement in MEN1. Analysis of 715 cases from the Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines database. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;166:269–279. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlen JE, Buethe DD, Culkin DJ, Slobodov G. Multiple endocrine neoplasia 2a presenting with pheochromocytoma and pituitary macroadenoma. ISRN Oncology. 2011;2011:732452. doi: 10.5402/2011/732452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen K. Acromegaly associated with phaeochromocytoma. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1952;142:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1952.tb13837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson KL, Roberts JA, Varela M. Multiple endocrine adenomatosis: in support of the common origin theories. Journal of Urology. 1978;119:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki S, Baba Y, Kakita T, Yamamoto H, Fukase M, Goto Y, Seino Y, Kato Y, Matsukara S, Imura H. A case of acromegaly associated with pheochromocytoma [in Japanese] Saishin-lgaku. 1976;31:1402–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn MT, Mullon DA. Pheochromocytoma without hypertension, report of a patient with acromegaly. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1964;188:74–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03060270080022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Progress in Brain Research. 2010;182:343–373. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)82015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Jiménez E, de Campos JM, Kusak EM, Landa I, Leskelä S, Montero-Conde C, Leandro-García LJ, Vallejo LA, Madrigal B, Rodríguez-Antona C, et al. SDHC mutation in an elderly patient without familial antecedents. Clinical Endocrinology. 2008;69:906–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manger WM, Gifford RW., Jr . Pheochromocytoma. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag; 1977. pp. 284–286. [Google Scholar]

- McWhinney SR, Pasini B, Stratakis CA International Carney TriadCarney–Stratakis Syndrome Consortium. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors and germ-line mutations. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1054–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melicow MM. One hundred cases of pheochromocytoma (107 tumors) at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, 1926–1976: a clinicopathological analysis. Cancer. 1977;40:1987–2004. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<1987::AID-CNCR2820400502>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DH. Association of phaeochromocytoma and prolactinoma. Medical Journal of Australia. 1982;1:13–14. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1982.tb132108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JH, Eversman JJ. Acromegaly, hyperparathyroidism, and pheochromocytoma in the same patient. A multiple endocrine disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1981;141:1521–1522. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1981.00340120129027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, Bausch B, McWhinney SR, Muresan M. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:943–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, Zbuk KM, Sadler T, Patocs A, Lobo G, Edelman E, Platzer P, Orloff MS, Waite KA, Eng C. Germline mutations and variants in the succinate dehydrogenase genes in Cowden and Cowden-like syndromes. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;83:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins NJ, Cullen MJ, Heffernan AG. A case of acromegaly and phaeochromocytoma. Journal of the Irish Medical Association. 1967;60:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osamura Y, Watanabe K, Nomoto Y, Sasaki H, Katsuoka Y. Acromegaly, pheochromocytoma, adrenal cortical adenoma and Grawitz tumor in a patient. Presented at the Ninth Meeting on the Functioning Tumours; Tokyo. October 1977.1977. [Google Scholar]

- Oyedotun KS, Lemire BD. The quaternary structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate dehydrogenase. Homology modeling, cofactor docking, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:9424–9431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311876200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimundo N, Baysal BE, Shadel GS. Revisiting the TCA cycle: signaling to tumor formation. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2011;17:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raygada M, Pasini B, Stratakis CA. Hereditary paragangliomas. Advances in Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2011;70:99–106. doi: 10.1159/000322484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth KA, Wilson DM, Eberwine J, Dorin RI, Kovacs K, Bensch KG, Hoffman AR. Acromegaly and pheochromocytoma: a multiple endocrine syndrome caused by a plurihormonal adrenal medullary tumor. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1986;63:1421–1426. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-6-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Miura D, Taguchi M, Takeshita A, Miyakawa M, Takeuchi Y. Coincidence of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A with acromegaly. American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010;340:329–331. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e73fba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-α prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson J, Giordano TJ, Avram AM. Three endocrine neoplasms: an unusual combination of pheochromocytoma, pituitary adenoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2011;22:430–436. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleilati GG, Kovacs KT, Honasoge M. Acromegaly and pheochromocytoma: report of a rare coexistence. Endocrine Practice. 2002;8:54–60. doi: 10.4158/EP.8.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EH, Janknecht R, Maher LJ., III Succinate inhibition of α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes in a yeast model of paraganglioma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16:3136–3148. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AL, Goodman AD, Powers SR. Study of a kindred with pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, hyperparathyroidism and Cushing’s disease: multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2. Medicine. 1968;47:371–409. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh BT, Hansen J, Svensson PJ, Hartley L. Bilateral recurrent phaeochromocytoma associated with a growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumour. British Journal of Surgery. 1996;83:1132. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakker RV. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;24:355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanharanta S, Buchta M, McWhinney SR, Virta SK, Peçzkowska M, Morrison CD, Lehtonen R, Januszewicz A, Järvinen H, Juhola M, et al. Early-onset renal cell carcinoma as a novel extraparaganglial component of SDHB-associated heritable paraganglioma. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;74:153–159. doi: 10.1086/381054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohllk N, Schweizer H, Erlic Z, Schmid KW, Walz MK, Raue F, Neumann HP. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;24:371–387. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf LM, Duduisson M, Schrub JC, Metayer J, Laumonier R. Sipple’s syndrome associated with pituitary and parathyroid adenomas. Annales d’Endocrinologie. 1972;33:455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xekouki P, Pacak K, Almeida M, Wassif CA, Rustin P, Nesterova M, de la Luz Sierra M, Matro J, Ball E, Azevedo M, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) D subunit (SDHD) inactivation in a growth-hormone-producing pituitary tumor: a new association for SDH? Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:E357–E366. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Ma G, Liu X, Zhang H, Deng H, Nowell J, Miao Q. Primary cardiac pheochromocytoma with multiple endocrine neoplasia. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2011;137:1289–1291. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-0985-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]