Abstract

Study aims were to identify subgroups of adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms who had the highest likelihood of developing future major/minor depressive disorder on the basis of depression risk factors and participation in three depression prevention programs, with the goal of evaluating the preventive effect of indicated prevention interventions in the context of known risk factors. Adolescents (N = 341) with elevated depressive symptoms were randomized to one of four prevention intervention conditions (cognitive-behavioral group, supportive-expressive group, cognitive-behavioral bibliotherapy, educational brochure control). By 2-year follow-up, 14% showed onset of major/minor depressive disorders. Classification tree analysis (CTA) revealed that negative attributional style was the most important risk factor: youth with high scores showed a 4-fold increase in depression onset compared to youth who did not endorse this attributional style. For adolescents with negative attributional style, prevention condition emerged as the most important predictor: those receiving bibliotherapy showed a 5-fold reduction in depression disorder onset relative to adolescents in the three other intervention conditions. For adolescents who reported low negative attributional style scores, elevated levels of depressive symptoms at baseline emerged as the most potent predictor. Results implicate two key pathways to depression involving negative attributional style and elevated depressive symptoms in this population, and suggest that bibliotherapy may offset the risk conveyed by the most important depression risk factor in this sample.

Keywords: depression, prevention, risk factors, adolescents, CTA

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders among adolescents with approximately 20% experiencing major depressive disorder (MDD) and 15% experiencing minor depression (e.g., Kessler & Walters, 1998; Newman et al., 1996). Adolescent depression increases risk for suicide attempts, substance abuse, academic problems, antisocial behavior, and interpersonal problems (e.g., Newman et al. 1996; Reinherz, Giaconia, Hauf, Wasserman, & Silverman, 1999). The majority of depressed adolescents, however, do not receive treatment (Newman et al., 1996). Thus, developing effective adolescent depression prevention programs is crucial. Meta-analytic reviews suggest that selective prevention programs (i.e., targeting subgroups with risk factors for depression) and indicated prevention programs (i.e., targeting adolescents who are experiencing early signs of depression) produce larger effects than universal programs (Horowitz & Garber, 2006; Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2008).

The present study used data from a trial of a brief group cognitive-behavioral (CB) indicated depression prevention program for adolescents. In this study, 341 adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms were randomized to a group CB intervention, group supportive-expressive intervention, CB bibliotherapy, or brochure control. Through 6-month follow-up, group CB participants showed greater reductions in depressive symptoms than those in the three other conditions, as well as reduced risk for major depression compared to brochure controls (Stice, Rohde, Seeley, & Gau, 2008). Group CB participants also showed greater reductions in depressive symptoms than bibliotherapy and brochure control participants by 1- and 2-year follow-up (Stice, Rohde, Gau, & Wade, 2010); in addition, risk for onset of major or minor depression over 2-year follow-up was lower for both group CB participants (14%; OR = 2.2) and CB bibliotherapy participants (3%; OR = 8.1) compared to brochure controls (23%).

Although research (e.g., Garber et al., 2009; Young, Mufson, & Davies, 2006) is providing encouraging evidence for various depression prevention interventions, studies have yet to evaluate the effects of these interventions when examined in the context of established risk factors. We used classification tree analyses (CTA; Lemon, Roy, Clark, Friedmann, & Rakowski, 2003) to examine the predictive effects of three prevention programs relative to the effects of depression risk factors because this approach is well suited to identifying nonlinear interactions when predicting dichotomous outcomes (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002), such as depressive disorder, and the identification of subgroups that respond particularly well or particularly poorly to an intervention. CTA is a recursive partitioning strategy that generates a classification tree describing mutually exclusive subgroups that have high (or low) probability of developing depressive disorders based on risk factor combinations. CTA identifies the precise cutpoints that best differentiate youth at high versus low risk for disorder onset and are easy to interpret (Yarnold & Soltysik, 2005), which increase their clinical utility. As an exploratory technique, CTA is well suited for situations such as the present study, in which there are few data or predictions regarding the ways in which depression prevention interventions do or do not interact with pre-existing depression risk factors.

We used CTA to address two novel questions regarding the intervention effects in the present depression prevention trial. First, we used CTA to test of whether the effects of these prevention programs were potent enough to emerge within the context of depression risk factors: these interventions could either exert a more potent effect on risk for depressive disorder onset than established risk factors (i.e., have a main effect) or significantly offset the risk conveyed by an established risk factor (i.e., moderate the effect of that risk factor). Second, we used CTA to test whether the risk factors moderated the effects of interventions on risk for depressive disorder onset. An earlier report examined factors that moderated effects of the group CB prevention program relative to brochure control on a continuous depressive symptom measure over six-month follow-up (Gau, Stice, Rohde, & Seeley, in press): group CB was superior to brochure control among adolescents who endorsed low/medium levels of either substance use or negative life events, but was comparable to brochure control at high levels of either substance use or negative events. Initial depression severity, perceived social support, and motivation to reduce depression did not moderate group CB effects. In contrast, the current study examined moderators of the effects of all three interventions on risk for depressive disorder onset over 2-year follow-up. Knowledge of factors that reduce the effectiveness of a prevention program provides direction for developing more effective interventions. Conversely, discovering factors that enhance the effects of prevention programs identify subgroups that should be targeted in prevention-matching approaches. Results may also identify exclusion criteria that could be used to avoid delivering interventions to subpopulations that are unlikely to benefit.

We examined the following variables, each of which has received support as a risk factor for adolescent depression: depressive symptoms, past MDD, hopelessness, negative cognitions, negative attributional style, poor self-esteem, loneliness, low social support, negative life events, poor social adjustment, substance use, low motivation to reduce depression, sex, race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1996; Schaap, Hoogduin, Hoogsteyns, & de Kemp, 1999; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Reinherz et al., 1999; Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1997; Seeley, Stice, & Rohde, 2009). Examining several variables provided an opportunity to identify distinct pathways to depressive disorders, which has been seldom done (Garber, 2006).

Method

Participants

Participants were 341 high school students (56% female) ages 14 to 19 years (M = 15.6; SD = 1.2). The sample was composed of 2% Asians, 9% African Americans, 46% Caucasians, 33% Hispanics, and 10% who specified other, which was slightly more diverse than the greater Austin area (7% African American, 18% Hispanic, 65% Caucasian). Parental educational attainment was 26% high school graduate or less; 17% some college; 35% college graduate; 18% graduate degree, which was somewhat higher than this population (34% high school graduate or less; 25% some college; 26% college graduate; 15% graduate degree).

Procedures

Participants were recruited between 2004 and 2007 using mailings, handbills, and posters that invited students experiencing sadness to participate in a trial of interventions designed to improve current and future mood. Interested students were given the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) and an adolescent assent form and a parental consent form to be signed. Those scoring 20 or higher were invited for a pretest assessment. We selected this cutoff because an epidemiologic study (Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991) found that 31% of community-dwelling adolescents scored above 20 on the CES-D and this cutoff appeared to maximize sensitivity for detecting youth at risk for major depression. Those who met criteria for current major depression (n = 68) were excluded and given treatment referrals.

Participants were randomly assigned using computer-generated random numbers to: (1) group CB (n = 89), (2) group supportive-expressive (n = 88), (3) CB bibliotherapy (n = 80), or (4) brochure control (n = 84). Stice et al. (2008) provides additional trial information.

Participants completed a survey and interview at pretest, posttest, 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-ups, receiving $20 per assessment. Assessors, who were blind to condition, had at least a BA in psychology and received 40 hours of training. Assessors were required to maintain a k > .80 for diagnoses of depressive disorders on the K-SADS. Assessments and groups were conducted at the schools. The local Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Intervention Conditions

Group CB focused on increasing fun activities, learning cognitive restructuring, and developing a stress response plan. Goals of the supportive-expressive group were to establish and maintain rapport, provide support, and express feelings. Both group interventions consisted of six weekly 1-hour group sessions containing 3–10 same-sex participants that were facilitated by clinical psychology graduate students and co-facilitated by undergraduate students. Manuals for interventions contained a program rationale, facilitator guidelines, and outlines for each session. Bibliotherapy participants were given copies of Feeling Good (Burns, 1980), a highly regarded and empirically supported self-help book (Mains & Scogin, 2003; Redding, Herbert, Forman, & Gaudiano, 2008), and were encouraged to read the book at their own pace. Participants in the brochure control condition were given an NIMH brochure describing depression and treatment options (“Let’s Talk About Depression” Pub. 01-4162), as well as local referral information.

Measures

Demographic factors including sex, age, parental education (maximum parental education on 6-point scale), and race/ethnicity (dichotomized into minority vs. majority status) were assessed by survey items.

Depressive symptoms and diagnosis were assessed with 16 items measuring MDD symptoms (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) adapted from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997); the scoring of items on this semi-structured interview was modified to better capture the timing of symptom occurrence. Adolescents reported peak severity of each symptom over their lifetime and the past month at baseline or since the last interview at follow-ups on a month-by-month basis. Items used a 4-point response format (1 = not at all to 4 = severe symptoms). We averaged across the 13 items that assessed symptoms (3 additional items referred to impairment, substance-induced depression, and bereavement) to form a continuous symptom composite for the past month at baseline. Responses were also used to determine whether participants met criteria for major or minor depression. Inter-rater reliability in a randomly selected 5% of the sample indicated agreement for diagnoses (k = .83) and the symptom composite (r = .85).

Hopelessness was assessed with the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974), a 20-item true-false inventory. The scale showed internal consistency (α = .78) and one-month test-retest reliability in controls (r = .71).

Negative cognitions were assessed with 12 5-point (1 = not at all to 5 = all the time) items from the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ; Hollon & Kendall, 1980). Items from the personal maladjustment/desire for change and negative self-concept subscales were used because they had correlated .98 with total ATQ score (Rohde, Clarke, Mace, Jorgensen, & Seeley, 2004). The scale showed internal consistency (α = .93) and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .75).

Attributional style was assessed with 12 items from the Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire (ACSQ: Hankin & Abramson, 2002), which presents positive and negative events; participants rate the degree to which they believe the event is internal, stable, global, and signifies that the person is flawed using 7-point response options. The scale showed internal consistency (α = .85) at baseline and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .67).

Self Esteem was assessed with 4 items from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg 1979) measuring beliefs and attitudes regarding general self-worth. The scale showed internal consistency (α = .83) at baseline and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .74).

Parental and peer support were measured with 12 5-point (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) items selected from the Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985). Items were averaged to form parent and peer support scales. The parent and peer scales showed internal consistency (α = .84 and α = .87, respectively) and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .70 and r = .75, respectively).

Loneliness was assessed with an 8-item Loneliness Scale adapted by Lewinsohn et al. (1994) from Russell (1996). The scale showed internal consistency (α = .83) and 3-week test-retest reliability (r = .74).

Social adjustment was assessed with 17 items from the Social Adjustment Scale-Self Report for Youth (Weissman, Orvaschel, & Padian, 1980) measuring family, peer, and school functioning (response options: 1 = never to 5 = always). The scale showed internal consistency (α = .71) and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .74).

Negative life events were assessed with an adapted version of the Major Life Events scale (Lewinsohn et al., 1994), which measured the occurrence of 14 events in the past year (response options: 1 = no to 3 = at least twice). This scale has shown predictive validity for future MDD (Lewinsohn et al., 1994) and showed internal consistency (α = .58).

Motivation to reduce depression was assessed by a 4-item 5-point (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) scale developed for this project. This scale showed internal consistency (α = .93) and 1-week test-retest (r = .83) in pilot testing (N = 44). In the present study the scale showed internal consistency (α = .82).

Substance use was assessed with 10 items were adapted from Johnston, O’Malley, and Bachman (1989). Adolescents reported consumption of various substances during the past 6 months, as well as number of drinks consumed per drinking episode and cigarettes smoked daily. The scale showed internal consistency (α = .78) and one-month test-retest reliability (r = .71).

Data Completeness and Analytic Plan

Three percent of participants did not provide data at posttest, 15% at 1-year follow-up, and 22% at 2-year follow-up. Number of completed assessments was not associated with condition or demographic factors. Intent-to-treat analyses using maximum likelihood estimates were used.

CTA models are calculated by testing all possible separations (of categorical variables) or cutpoints (of continuous variables), usually by comparing the chi-square statistic in relation to the categorical outcome. Trees are fitted using a recursive partitioning approach that selects the optimal cut-point on the most potent risk factor (parent node) for generating subgroups that have the greatest differential risk for the categorical outcome. This procedure is repeated on resulting subgroups (child nodes) until there are no remaining predictors that identify subgroups at significantly differential risk or the node sizes become too small. When different risk factors emerge for two branches from the same fork, it signifies a moderation effect. To evaluate the nature and success of classification of the CTA model as branches are added to the tree, we computed sensitivity (i.e., % of disorder onset cases correctly identified by the model), specificity (i.e., % of disorder-free cases correctly identified by the model), positive predictive value (PPV; % of predicted onset cases that were true cases), and negative predictive value (NPV; % of non-predicted onset cases that were true non-cases) after each model split.

Confidence in CTA models increase with replication of results. When the sample is too small for independent cross-validation, as was our situation, it is recommended that sample subsets be used for cross-validation (e.g., Steinberg & Colla, 1997). We conducted a tenfold cross-validation procedure to determine the optimal tree size and structure. In this procedure, the sample is divided into ten independent groups (each containing 10% of the sample). Ten trees are constructed that each use a randomly selected nine-tenths of the sample (i.e., each leaving out a different 10%). The final tree is the one that shows the best average accuracy for cross-validated predicted classifications or predicted values. Generally, this tree is not the most complex.

Another significant issue in CTA concerns the decision of when to stop splitting nodes, given that with enough splits the model will perfectly classify all cases in the original dataset but is unlikely to be replicated. Our stopping rule was based on minimum size for child nodes (Lemon et al., 2003). The Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID) growing method was used and the minimum node size was set at 20 for the parent (i.e., initial) node and 10 for child (i.e., subsequent) nodes to minimize Type I error and influential outliers. The significance levels for splitting nodes were set at p < .05 and were adjusted using a Bonferroni method.

Results

Frequency of Occurrence of Depressive Disorder Onset

By the 2-year follow-up, 46 (14%) of the participants had onset of major depression (40 cases) or minor depression (6 cases): 19 (23%) of brochure control participants, 12 (14%) of group CB participants, 13 (15%) of group supportive expressive participants, and 2 (3%) of CB bibliotherapy participants. As reported previously (Stice et al., 2010), group CB participants (β = 0.80; SE = 0.38; p = .033; OR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.07–4.67) and bibliotherapy participants (β = 2.10; SE = 0.75; p = .004; OR = 8.13; 95% CI = 1.89–34.96) showed significantly lower risk for onset of depressive episodes during the 2-year follow-up than brochure controls, using Cox proportional hazard models (2-tailed tests); all other condition comparisons were nonsignificant.

Descriptive Information Regarding Risk Factor Variables

Table 1 contains the intercorrelation matrix for the 17 risk factors and the correlations between the outcome measure and each risk factor. Also shown are means and standard deviations for continuous measures and percent occurrence for dichotomous measures. The 4 demographic factors had low, generally nonsignificant associations with the other risk factors and none was correlated with depressive disorder onset. The remaining 13 risk factors were in general correlated with each other and had an absolute average intercorrelation r = .28; 8 of these 13 variables were significantly correlated with the outcome measure. Negative cognitions had the largest absolute intercorrelation among the other risk factors (r = .41), followed by social adjustment (r = .37), and attributional style (r = .35).

Table 1.

Intercorrelation Matrix of Examined Risk Factors

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. female sex | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. age | −.01 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. low parental education | −.14 | −.06 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. minority status | .05 | −.04 | −.34 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| 5. MDD symptom severity | .09 | .07 | −.05 | .14 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||

| 6. past history of MDD | .10 | .12 | −.01 | −.08 | .30 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| 7. hopelessness | −.03 | .03 | .05 | −.01 | .36 | .15 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| 8. negative cognitions | .10 | .07 | .04 | .02 | .54 | .29 | .56 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 9. attributional style | .08 | .18 | .01 | −.08 | .40 | .22 | .36 | .60 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| 10. self-esteem | −.10 | −.05 | .07 | −.04 | −.37 | −.16 | −.57 | −.59 | −.34 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 11. social support from family | −.08 | −.03 | .05 | .04 | −.24 | −.10 | −.30 | −.28 | −.35 | .35 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 12. social support from friends | .23 | −.05 | −.03 | .05 | −.20 | −.11 | −.27 | −.28 | −.18 | .30 | .19 | 1.0 | |||||

| 13. loneliness | .02 | .20 | .03 | −.06 | .35 | .22 | .40 | .52 | .43 | −.52 | −.28 | −.50 | 1.0 | ||||

| 14. social adjustment | .03 | .09 | .01 | −.05 | .38 | .21 | .37 | .52 | .56 | −.41 | −.34 | −.34 | .52 | 1.0 | |||

| 15. stressful events | −.08 | −.13 | −.13 | .06 | .21 | −.03 | .18 | .22 | .26 | −.14 | −.23 | −.23 | .10 | .30 | 1.0 | ||

| 16. motivation reduce depression | .24 | −.01 | −.09 | .06 | .40 | .21 | .17 | .44 | .35 | −.22 | −.10 | −.04 | .25 | .35 | .14 | 1.0 | |

| 17. substance use | −.02 | .11 | .03 | −.16 | .06 | .15 | .10 | .09 | .18 | −.05 | −.18 | −.02 | −.01 | .13 | .22 | −.04 | 1.0 |

| Mean (% occurrence for #1, 3, 4, 6) | 56.3 | 15.5 | 45.2 | 46.4 | 1.8 | 27.5 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 10.6 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 22.4 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 0.5 |

| Standard deviation | NA | 1.2 | NA | NA | 0.3 | NA | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Correlation with outcome measure | .07 | .08 | .03 | .02 | .27 | .10 | .10 | .25 | .28 | −.18 | −.10 | −.03 | .19 | .21 | .08 | .16 | −.02 |

Notes. Italicized correlations are significant at italicized at p < .01, underlined correlations at p < .001.

Classification Tree Analysis

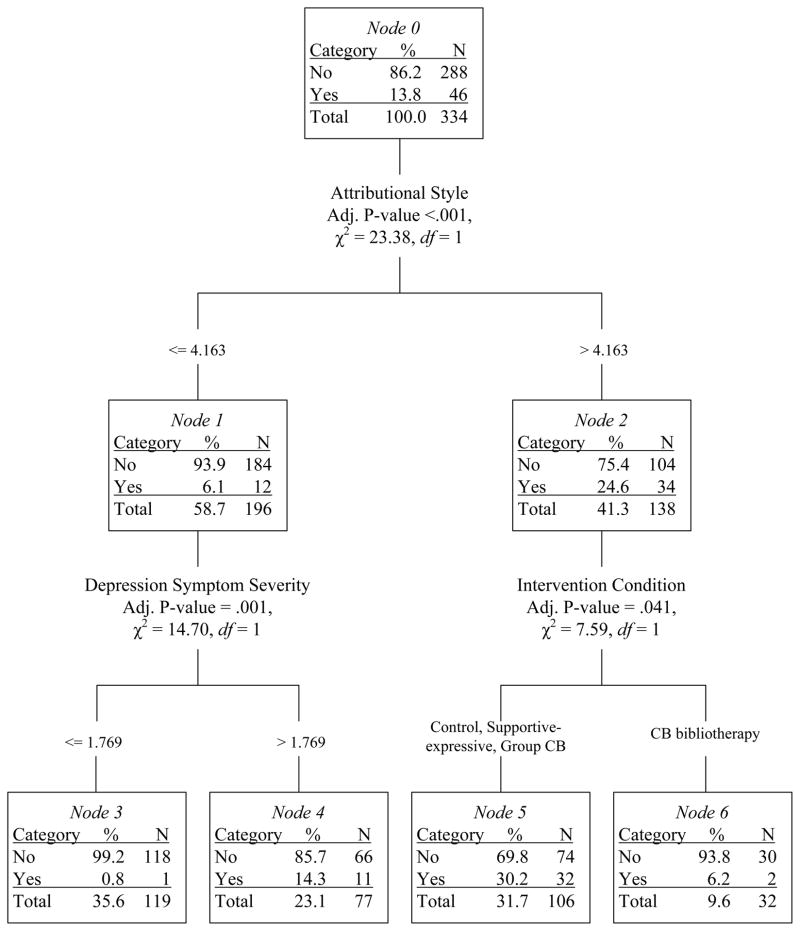

The risk factors and intervention condition (condition was entered as a 4-level categorical variable; 0 = control, 1 = supportive-expressive, 3 = CB bibliotherapy, 4 = CB group) were entered into a CTA with tenfold cross-validation. The model produced a classification tree with three forks and four terminal nodes (Figure 1). The first fork consisted of negative attributional style, which emerged as the most potent predictor of depressive disorder onset. Adolescents with high levels of negative attributional style showed a four-fold increase in risk for depressive disorder onset (24.6% vs. 6.1%; χ2 (1, N = 334) = 23.38, p <.001; OR = 5.01, 95% CI = 2.49–10.10). This first fork correctly identified 74% of the depression onset cases (sensitivity) and 64% of the non-onset cases (specificity). Of the predicted onset cases, 25% were true cases (PPV) and 94% of the predicted non-cases were true non-cases (NPV).

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of CTA decision rules predicting onset of major/minor depression with baseline variables and prevention intervention conditions. Empirically derived cut-points are shown, along with the sample size and the incidence rate for depression onset for each branch and node.

An additional branch emerged for participants with high negative attributional style: prevention condition. Adolescents randomly assigned to CB group, supportive-expressive group, and brochure control were at five times greater risk of experience depressive disorder compared to adolescents assigned to bibliotherapy (depressive disorder incidence rate = 30.2% vs. 6.2%; χ2 (1, N = 138) = 7.59, p = .041; OR = 6.49, 95% CI = 1.46–28.79). The addition of this second fork improved specificity and PPV, correctly identifying 70% of the depression onset cases (sensitivity) and 74% of the non-onset cases (specificity). Thirty percent of the predicted onset cases were true cases (PPV) and 94% of the predicted non-cases were true non-cases (NPV).

Among adolescents with a low negative attributional style, an additional fork emerged. Elevated depressive symptoms emerged as a risk factor among adolescents with low negative attributional style (depressive disorder incidence rate = 14.3% vs. 0.8%; χ2 (1, N = 196) = 14.70, p = .001; OR = 19.07, 95% CI = 2.48–155.72). The addition of this third fork greatly improved correct identification of depression onset cases (specificity = 93%), and correctly identified 52% of the non-cases. Of the predicted onset cases, 23% were true cases (PPV) and 98% of the predicted non-cases were true non-cases (NPV).

In sum, the CTA model revealed two two-way interactions (i.e., high attributional style X prevention program; low attributional style X depressive symptoms). The final CTA resulted in an 86.2% accuracy rate (percent of total sample correctly classified by the tree model) in predicting major/minor depressive disorder onset, which provides an overall index of the predictive accuracy of the model, akin to an R-squared value for a linear regression model.

Discussion

The present study sought to identify subgroups of adolescents who were at elevated risk for future major or minor depressive disorder, using a set of established depression risk factors and whether the adolescent had participated in one of three depression prevention interventions, each of which was previously shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms or onset of depressive disorder to varying degrees (Stice, Rohde et al., 2008; 2010). Negative attributional style was selected as the first predictor of depressive disorder in this high-risk sample, indicating that it differentiated the two groups that varied most strongly in rates of depressive disorder onset. Adolescents who endorsed a negative attributional style (at the cutpoint determined by the CTA model) had a four-fold increase in depression onset, with almost one-quarter of that subgroup developing a diagnosis of depression during the 2-year follow-up.

A primary aim of this study was to examine whether, by including three indicated prevention interventions in the context of various risk factors, any evidence emerged that one or more of the depression prevention programs expressly counteracted the effects of examined risk factors; that association emerged in the second branch of the CTA model. Namely, among adolescents who endorsed high levels of negative attributional style, prevention condition was selected as the next predictor, with bibliotherapy resulting in significantly lower risk of future depressive disorder onset compared to the two other active prevention interventions and the brochure control group, which did not significantly differ. The risk of subsequent depressive disorder among adolescents with a negative attributional style who received bibliotherapy was 6% compared to 30% for adolescents in the other three conditions, suggesting that bibliotherapy offset the risk for future depressive disorders conveyed by the most potent risk factor in this sample (i.e., the risk level for this subgroup of bibliotherapy recipients matched the risk level for participants who did not evidence negative attributional style). Although the group CB, supportive-expressive, and control conditions are qualitatively different, the CTA algorithm grouped these three conditions together because the incidence for depressive disorder onset was more similar for these three conditions than for the bibliotherapy condition.

The present results suggest an important role for attributional style in predicting adolescent depression. Attributional style refers to how an individual responds to difficult events in his or her life. A negative attributional style involves the person seeing negative events as stable, internal, and global, and is a specific vulnerability factor featured in the hopelessness depression subtype (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). It is important to note that Abramson and colleagues propose a diathesis-stress model, in which negative events occur in conjunction with the attributional style to trigger depression onset. We did not find that interaction but also did not closely track the occurrence of major life events. Attributional style has been found to moderate the impact of stress in predicting symptoms of hopelessness depression but not depression more generally (Abela, Parkinson, Stolow, & Starrs, 2009). Alloy and colleagues (Alloy et al., 2000) found that college students elevated on this cognitive style measure were at significantly higher risk for MDD and the hopelessness depression subtype.

The CTA findings raise the intriguing question of why bibliotherapy was so effective in preventing the onset of depressive disorder in adolescents with subthreshold depression who endorsed a negative attributional style whereas group CB fared no better than a supportive-expressive group or receiving an informational brochure in preventing depression disorders in this high-risk subgroup. Previously, we found that, compared to brochure controls, bibliotherapy significantly reduced depressive symptoms at 6-months post-intervention but that differences by 1- and 2-year follow-up were nonsignificant. Conversely, group CB, relative to brochure control, was associated with significant or near significant effects at 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up (p < .001, .023, and .056, respectively), which suggests that group CB has superior effects in reducing depressive symptoms compared to bibliotherapy. However, we also reported that bibliotherapy was associated with very low rates of depressive disorder onset for the entire sample, although rates for bibliotherapy versus group CB did not statistically differ (3% vs. 14%, respectively; Stice et al., 2010). The present findings suggest that bibliotherapy may be particularly effective for the subset of mildly depressed adolescent who endorse the pessimistic attributional style.

Ackerson, Scogin, McKendree-Smith, and Lyman (1998) examined the efficacy of bibliotherapy (using Feeling Good) for 22 adolescents experiencing mild/moderate depressive symptoms. Bibliotherapy was superior to a delayed control condition, with improvements in depressive symptoms maintained at 1-month follow-up. Bibliotherapy also resulted in a significant decrease in dysfunctional thoughts (but not in negative automatic thoughts). Meta-analyses with both adults and adolescents indicate that CB bibliotherapy outperforms assessment-only controls for depression treatment (Cuijpers, 1997; Gregory, Schwer-Canning, Lee, & Wise, 2004). The book Feeling Good provides almost an exclusive cognitive intervention focus and potentially teaches the adolescent much more cognitive restructuring than the CB group, which may be essential in preventing depression given the pessimistic attributional style. Although the book is over 700 pages, the cognitive model is presented in the first 50 pages, followed by numerous examples applying these techniques to various situations. We previously reported that, on average, bibliotherapy participants read 200 pages of the book, which would have provided a strong introduction to the model and would have taken approximately as much time as attending the CB group and completing home practice exercises (Stice et al., 2010). Further, of participants who read the book, 26% read it when depressed and 62% when bored. Possibly, having an intervention method in your possession when it is needed may have contributed to the success of bibliotherapy. Although continued examination of this cost-effective form of depression prevention is clearly needed, it needs to be acknowledged that bibliotherapy in the present study, as in other research, was not completely self-administered but occurred in a context of contact with research staff and clinical monitoring via the follow-up assessments; bibliotherapy may not be effective for individuals with severe depression, comorbid psychiatric conditions, suicidal tendencies, low levels of learned resourcefulness or motivation, or high defensiveness (Mains & Scogin, 2003). The degree to which bibliotherapy is truly more effective than a CB group interventions in preventing future depression among high-risk adolescents has important implications for dissemination efforts.

A second aim was to test whether risk factors moderated the effects of prevention programs. We found no CTA branches to indicate moderation. Whether this negative finding was due to limited power or the lack of moderating variables for risk for depressive disorder onset in the sample is unknown. Moderation analyses for the onset of depressive disorders may require large samples and perhaps a different approach that directly examines that issue.

The second major branch of the CTA model identified the most salient predictive factor for adolescents who did not endorse the pessimistic attributional style. Results suggested that, in the absence of a negative attributional style, elevated depressive symptoms serve as an alternate pathway to depressive disorders for at-risk adolescents. The presence of elevated depressive symptoms thus represents a second core risk group for future depressive episodes, which should be interpreted in light of the fact that elevated depressive symptoms was the inclusion criterion for this high-risk sample. To illustrate what the CTA model cutpoint score of 1.77 depressive symptoms means, adolescents reporting one severe symptom and one moderate symptom or those reporting six symptoms at the slight/mild level could receive a score near 1.77. Elevated depressive symptoms have emerged in previous research with unselected adolescent samples as the strongest risk factor and best single screening measure (e.g., Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Seeley et al., 2009).

In sum, the CTA model suggests two predictive pathways to depressive disorders in a high-risk group of adolescents. Among the 40% of this sample who endorsed a negative attributional style at the CTA-selected cutpoint, one quarter developed a depressive disorder within two years. For the remaining 60% who did not endorse the negative attributional style, elevated depressive symptoms captured almost all of the remaining cases of future depression (i.e., 45 of the 46 youth who developed future depressive disorder endorsed either negative attributional style or, in the absence of negative attributions, elevated depressive symptoms). Results suggest that these two subgroups would be highly relevant for inclusion in adolescent depressive prevention trials. It should be noted that the first pathway represents a selective approach, choosing participants for prevention based on a theoretically derived vulnerability, whereas the second pathway represents indicated prevention, selecting participants on the basis of early symptoms. Seligman, Schulman, DeRubeis, and Hollon (1999) evaluated this first approach, selecting 291 college students with elevated attributional style and randomizing them to CB group prevention or assessment control. After three years, those receiving the CB group had fewer episodes of generalized anxiety disorder, a trend for fewer MDD episodes, and fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms. In the present study, the attributional style risk factor appears to be counteracted by one of the examined prevention interventions – bibliotherapy.

Several negative findings warrant discussion. Contrary to findings with community samples (Bohon, Stice, Burton, Fudell, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Garrison et al., 1997; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Reinherz et al., 1999; Seeley et al., 2009), major life events, low social support, past MDD, female sex, negative cognitions, and substance use were not selected for inclusion in the CTA models. These negative findings do not necessarily mean that these variables are not important predictors of future depressive disorder. Rather, the CTA approach aims to maximize predictive sensitivity and specificity with the simplest tree structure. It is possible for variables that are not selected for the model to significantly predict onset of depressive episodes but their effect is “masked” by other correlated variables which have a stronger association with the outcome. Another negative finding was that no moderation effects emerged between high levels of two risk factors. That is to say, we found no instances in which the co-occurrence of two risk factors (e.g., high stress/low social support) exponentially increased the probability of future depression. This is noteworthy given that these types of interactions are proposed by several etiologic theories (e.g., cognitive diathesis-stress model, Beck, 1967; stress-buffering model, Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Study limitations should be noted. First, the sample size prohibited us from independently replicating a classification model. Second, because only 46 participants showed onset of depressive disorder during the follow-up, some of the CTA nodes contained only a small number of cases. A larger sample with more depression cases may have allowed the CTA to create a more complex classification model. Third, several risk factors were not assessed because of respondent burden concerns. Perhaps the most important missing risk factor was parental depression (e.g., Birmaher et al., 1996). Garber et al. (2009) found that a CB group prevention intervention was superior to usual care only in the absence of parental depression. Other potentially important risk factors include psychiatric comorbidity and child maltreatment (e.g., Kaufman, 1991; Lewinsohn et al., 1994). The classification properties of models using additional risk factors need to be examined. Fourth, CTA is less suited than logistic regression to identifying variables that have small effects spread across different groups or in characterizing the effects of continuous measures with linear effects. In addition, the method does not allow modeling of the nested nature of the data, does not optimally handle missing data, and does not permit the use of latent variable modeling. Other analytic techniques are better suited to addressing these issues, including hierarchical linear modeling for modeling the effect of the nested nature of data from trials of group interventions, survival models or maximum likelihood estimation procedures that better accommodate missing data, and latent variable modeling for theoretically reducing the effects of measurement error. We selected the CTA approach because it can be used to address some novel questions with data from prevention trials, which complement other analytic techniques that are suited to address qualitatively different research questions.

As recommended by Jaycox, Reivich, Gillham, and Seligman (1994), one should consider targeting multiple risk groups to maximize the reach of targeted prevention programs. For example, a screening strategy suggested by the current findings would be to assess adolescents for a negative attributional style and current depressive symptoms. Those endorsing the negative attributional style might be offered bibliotherapy, whereas youth reporting current depressive symptoms but no elevation on attributional style might receive group CB, which we previously found resulted in the fastest reductions in depressive symptoms (Stice, Rohde et al., 2008; 2010). These recommendations are speculative but research should test whether such tailored approaches to prevention produce even lower rates of subsequent depressive disorder onset relative to use of a single prevention program. Given the call for personalized interventions (e.g., National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2010), it is important to examine how various prevention and treatment interventions interact with pre-existing risk factors to identify the optimal methods of reducing the occurrence of future psychopathology in high-risk subgroups.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants MH067183 and MH080853 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Thanks go to project research assistants, Courtney Byrd, Kathryn Fischer, Amy Folmer, Cassie Goodin, Jacob Mase, and Emily Wade, a multitude of undergraduate volunteers, the Austin Independent School District, and the participants who made this study possible.

References

- Abela JRZ, Parkinson C, Stolow D, Starrs C. A test of the integration of the hopelessness and response style theories of depression in middle adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:354–364. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky FI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson J, Scogin F, McKendree-Smith N, Lyman RD. Cognitive bibliotherapy for mild and moderate adolescent depressive symptomatology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:685–690. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Robinson MS, Kim RS, Lapkin JB. The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression Project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:403–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, Perel J, Nelson B. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part 1. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohon C, Stice E, Burton E, Fudell M, Nolen-Hoeksema S. A prospective test of cognitive vulnerability models of depression with adolescent girls. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DD. Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: William Morrow & Company; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1997;28:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J. Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:S104–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, Beardslee WR, Brent DA, Gladstone TRG, DeBar LL, Lynch FL, D’Angelo E, Hollon SD, Shamseddeen W, Iyengar S. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2215–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Waller JL, Cuffe SP, McKeown RE, Addy CL, Jackson KL. Incidence of major depressive disorder and dysthymia in young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:458–465. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau JM, Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Negative life events and substance use moderate cognitive-behavioral adolescent depression prevention intervention. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.649781. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RJ, Schwer-Canning S, Lee TW, Wise JC. Cognitive bibliotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1980;4:383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Garber J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:401–415. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Reivich KJ, Gillham J, Seligman MEP. Prevention of depressive symptoms in school children. Behavior Research Therapy. 1994;32:801–816. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Drug use, drinking and smoking: National survey results from high school, college, and young adult populations 1975–1988. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J. Depressive disorders in maltreated children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:257–265. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao Uma, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depression & Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SC, Roy J, Clark M, Friedmann PD, Rakowski W. Classification and regression tree analysis in public health: Methodological review and comparison with logistic regression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:172–181. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Gotlib IH, Hops H. Adolescent psychopathology: II. Psychosocial risk factors for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:302–315. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE. Issues in prevention with school-aged children: Ongoing intervention refinement, developmental theory, prediction and moderation, and implementation and dissemination. Prevention & Treatment. 2001;4 Article 4, posted March 30 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mains JA, Scogin FR. The effectiveness of self-administered treatments: A practice-friendly review of the research. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:237–246. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Mental Health Council. Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council’s Workgroup. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 2010. From discovery to cure: Accelerating the development of new and personalizing interventions for mental illnesses. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton WR. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: Prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:552–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Redding RE, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Gaudiano BA. Popular self-help books for anxiety, depression, and trauma: How scientifically grounded and useful are they? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: Risks and impairments. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:500–510. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: A comparison of depression scales. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in the prevalence of adolescent depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Mace DE, Jorgensen JS, Seeley JR. An efficacy/effectiveness study of cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with comorbid major depression and conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:660–668. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121067.29744.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley JR, Stice E, Rohde P. Screening for depression prevention: Identifying adolescent girls at high risk for future depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0014741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Schulman P, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD. The prevention of depression and anxiety. Prevention & Treatment. 1999;2:Article 8. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg D, Colla P. CART–Classification and regression trees. San Diego, CA: Salford Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Gau JM, Wade E. Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: Effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:856–867. doi: 10.1037/a0020544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents outperforms two alternative interventions: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: Factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Padian N. Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales: Comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1980;168:736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnold PR, Soltysik RC. Optimal data analysis: A guidebook with software for windows. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Efficacy of Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training: an indicated preventive intervention for depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1254–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]