SUMMARY

We report that diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) commonly fails to express cell-surface molecules necessary for the recognition of tumor cells by immune-effector cells. In 29% of cases, mutations and deletions inactivate the β2-microglobulin gene, thus preventing the cell-surface expression of the HLA class-I (HLA-I) complex that is necessary for recognition by CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. In 21% of cases, analogous lesions involve the CD58 gene, which encodes a molecule involved in T and natural killer cell-mediated responses. In addition to gene inactivation, alternative mechanisms lead to aberrant expression of HLA-I and CD58 in >60% of DLBCL. These two events are significantly associated in this disease, suggesting that they are co-selected during lymphomagenesis for their combined role in escape from immune-surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common form of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 30–40% of cases (Abramson and Shipp, 2005). Based on gene expression profile (GEP) studies, three main subtypes have been identified, namely activated B-cell-like (ABC), germinal center B-cell-like (GCB), and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) (Staudt and Dave, 2005). These three subgroups appear to derive from distinct cells of origin, are associated with common as well as distinct genetic lesions, and, most notably, differ in their clinical response to conventional therapeutic regimens (Lenz and Staudt, 2010). Despite the significant progress in the identification of several key genetic lesions and associated deregulated pathways (Klein and Dalla-Favera, 2008; Lenz and Staudt, 2010), a sizable fraction of DLBCL remains incurable, suggesting that additional understanding in the pathogenesis of this disease is needed in order to develop more specific therapeutic approaches.

The recent availability of technologies such as next-generation sequencing and copy number analysis is leading to the identification of a large number of genetic alterations of possible pathogenetic significance in DLBCL (Morin et al., 2011; Pasqualucci et al., 2011b). These studies have confirmed that GCB-type DLBCLs are preferentially associated with t(14;18) translocations deregulating BCL2 (Huang et al., 2002), mutations within the BCL6 autoregulatory domain (Iqbal et al., 2007; Pasqualucci et al., 2003), and mutations of the chromatin modifier gene EZH2 (Morin et al., 2010). Conversely, alterations preferentially associated with ABC-DLBCLs include mutations leading to the constitutive activation of NF-κB (Compagno et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2010; Lenz et al., 2008; Ngo et al., 2010), translocations deregulating BCL6 (Iqbal et al., 2007; Ye et al., 1993), or inactivation events of BLIMP1 (Mandelbaum et al., 2010; Pasqualucci et al., 2006). In addition, genome-wide sequence and copy-number analyses have identified lesions common to all DLBCL subtypes, including the frequent inactivation of the acetyltransferase genes CREBBP and EP300 (Pasqualucci et al., 2011a) and the trimethyltransferase gene MLL2 (Morin et al.; Morin et al., 2011; Pasqualucci et al., 2011b). Among the many altered genes, we found β2-Microglobulin (B2M) and CD58, which were selected for further analysis given their potential role in the recognition of tumor cells by immune-surveillance mechanisms.

B2M is an invariant subunit required for the assembly of the class I human leukocyte antigen complex (HLA-I), which is present on the plasma membrane of most nucleated cells (Bjorkman et al., 1987) and is involved in the presentation of antigenic peptides derived from the degradation of endogenous self or non-self proteins (Peaper and Cresswell, 2008), including viral- or tumor-associated antigens (Townsend et al., 1985; Zinkernagel and Doherty, 1974). These peptides are then recognized by the T-cell receptors of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), leading to the destruction of the target cells that present non-self peptides. Several cancers, including colorectal carcinoma, melanoma, and cervical carcinoma, lack cell surface HLA-I expression due to heterogeneous mechanisms, thus allowing their escape from immune recognition by CTLs (Garrido et al., 2010; Hicklin et al., 1998). In particular, B2M gene lesions associated with defective HLA-I expression have been reported in a small number of lymphomas originating from the testis or the central nervous system (Jordanova et al., 2003).

CD58, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is a highly glycosylated cell adhesion molecule that is expressed in diverse cell types as a transmembrane or glycosylphosphatidylinositol-membrane-anchored form (Dustin et al., 1987; Springer et al., 1987). It acts as a ligand for the CD2 receptor, which is present on T cells and most natural killer (NK) cells, and is required for their adhesion and activation (Bolhuis et al., 1986; Kanner et al., 1992; Wang et al., 1999), as documented by the observation that CD58 monoclonal antibodies lead to the diminished recognition and cytolysis of the target cells by both CTLs and NK cells (Altomonte et al., 1993; Gwin et al., 1996; Sanchez-Madrid et al., 1982). Although certain cancers have been observed to downregulate CD58 (Billaud et al., 1990), the mechanisms underlying the lack of expression are largely unknown.

The present study reports the comprehensive characterization of a large panel of DLBCLs for the presence of B2M and CD58 genetic lesions as well as for the expression of the corresponding proteins. The observed alterations have consequences for the recognition of DLBCL by immune effector cells.

RESULTS

The B2M gene is targeted by mutations and deletions in DLBCL

Following the initial finding of B2M mutations in a “discovery panel” of 6 DLBCL cases (Pasqualucci et al., 2011b), we performed mutation analysis of the B2M coding exons in 126 additional DLBCL samples, including 105 primary biopsies and 21 cell lines (total n, including discovery cases =132). We discovered 25 sequence variants distributed in 14/111 (12.6%) DLBCL biopsies and 3/21 (14.2%) cell lines (Figure 1A and Table S1). Among these variants, twelve correspond to inactivating frameshift insertions/deletions (n=9) or nonsense mutations (n=3), resulting in transcripts that encode truncated B2M proteins. Of the remaining 13 missense variants, 38% (n=5) affect the initiator methionine and convert it to arginine, lysine, or threonine (ATG → AGG/AAG/ACG), thus abrogating protein expression, as previously documented in the Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line DAUDI (Rosa et al., 1983) (Figure S1A). Five additional missense mutations are expected to inactivate the protein function based on the PolyPhen prediction algorithm (Sunyaev et al., 2001), while the remaining three amino acid changes were located in the same allele carrying a premature stop codon, and may thus represent passenger events. The analysis of paired normal DNA in a subset of cases and the screening of several databases of population polymorphisms, including over 1000 normal individuals (see Methods), indicate that the observed mutations represent somatic events, overall accounting for 12.8% (n=17/132) of the DLBCL samples analyzed.

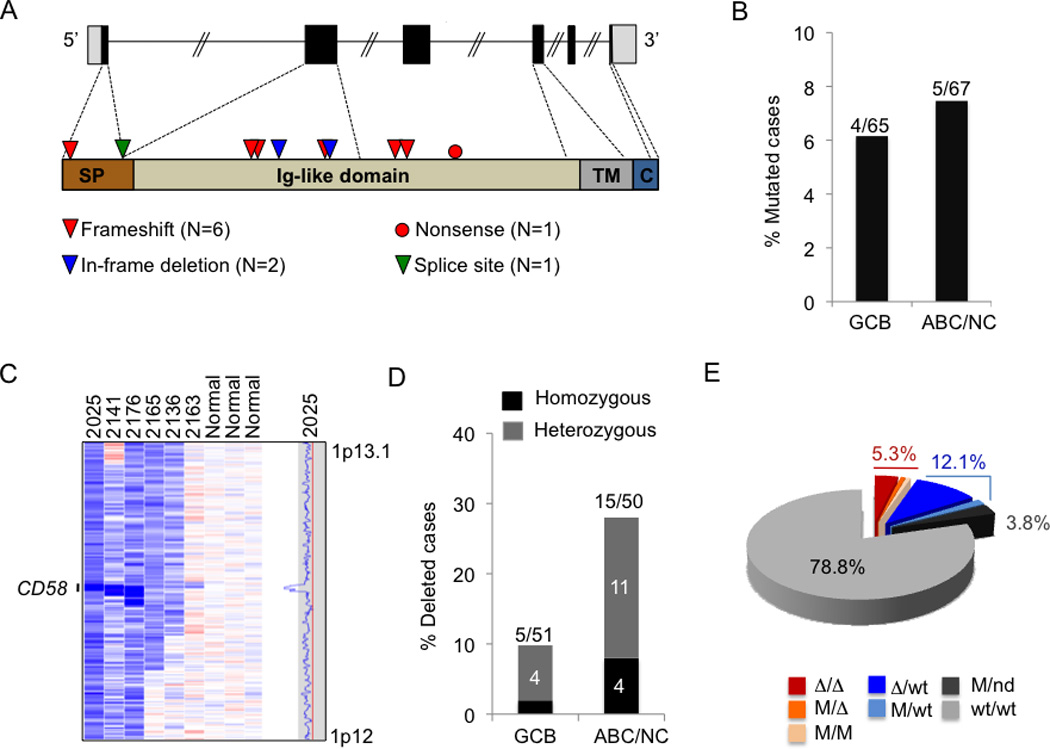

Figure 1. The B2M gene is targeted by genetic alterations in DLBCL.

(A) Schematic representing the distribution of missense, nonsense, and frameshift mutations affecting the B2M genomic region in DLBCL biopsies and cell lines (see also Table S1). (B) Percentage distribution of B2M mutated samples in the major DLBCL subtypes. (C) dChip copy number heat map illustrating focal deletions affecting the B2M locus (arrow) on chromosome 15 in representative DLBCL samples. The first three columns represent normal (diploid) samples (see also Figure S1 and Table S1). (D) Distribution of homozyogous and heterozygous deletions in ABC/NC and GCB DLBCL subtypes (see also Figure S1). (E) Overall frequency and allelic distribution of B2M alterations, including mutations and deletions, in DLBCL (Δ, deletion; M, mutation; WT, wild-type; nd, not determined).

B2M mutations are present in both the GCB (n=10/65) and ABC/non-classified (NC) (n=7/67) DLBCL subtype (Figure 1B), but were not found in other mature B-NHL analyzed (n=108 cases, including 37 follicular lymphomas, 16 Burkitt’s lymphomas, 44 chronic lymphocytic leukemias and 11 marginal zone lymphomas). These results suggest a specific role in the pathogenesis of DLBCL.

To investigate whether the B2M locus is also a target of copy number losses, we analyzed the 21 DLBCL cell lines and 80 of the 111 DLBCL biopsies (for which adequate material was available) by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and high-density SNP array analysis, respectively. Using these approaches, we observed recurrent deletions affecting the B2M locus in 24.7% (n=25/101) of the cases (Figure 1C for representative examples, and Figure S1B,C). Notably, 40% (n=10/25) of the affected samples harbored homozygous deletions (Figure 1C and Figure S1C), an event only rarely observed in other cancers with B2M lesions (Garrido et al., 2010). The majority of the biallelic losses (n=9) are <200 kb in size and identify a minimal region of deletion centered on the B2M locus. In fact, the smallest deletion (sample 2126) spans only ~30 Kb and selectively targets the B2M gene (Figure 1C and Table S1). Fifteen additional samples showed heterozygous B2M deletions, of which four likely represent subclonal events.

A combined analysis of both sequencing and copy-number data reveals that 12.9% of cases (n=17/132) have lost both B2M alleles due to homozygous deletions (n=9), biallelic mutations (n=4), or hemizygous deletions with mutations affecting the second allele (n=4), while 13.6% of cases (n=18/132) harbor monoallelic deletions (n=12) or mutations (n=6) (Figure 1E and Table S2). In three additional cases carrying truncating mutations, the status of the second allele could not be determined due to the lack of suitable material for SNP array or FISH analysis. The distribution frequency of B2M aberrations is comparable in GCB and ABC/NC DLBCLs, accounting for 32.3% and 25.3% of the cases, respectively (Figure S1D). Thus, overall 29% (n=38/132) of all DLBCLs harbor genetic lesions affecting the B2M locus, suggesting a critical role for this gene in the pathogenesis of the disease.

B2M missense mutations affect protein stability

While the majority of the B2M mutations identified were represented by unambiguously inactivating events, four of the biallelically-affected samples harbored a missense mutation in one of the two alleles (in the absence of secondary frameshift or nonsense mutations in cis) (Table S2). These four samples lack B2M expression by immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis (Figure 2A,B and Table S2), despite the presence of detectable B2M RNA expression (data not shown). These observations prompted us to investigate whether B2M missense mutations induce protein instability. Towards this end, we introduced lentiviral vectors encoding WT or missense mutant B2M alleles into WSU, a DLBCL cell line lacking B2M protein expression due to biallelic B2M gene inactivation (Table S2). All B2M missense variant alleles expressed significantly less protein relative to the WT allele, despite the presence of comparable B2M RNA levels, as measured by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 2C). Taken together, the results of the IHC and transient transfection analysis indicate that missense mutations cause the production of unstable B2M proteins.

Figure 2. B2M missense mutations affect protein stability.

(A) Schematic representation of the B2M protein, with its N-terminal signal peptide (SP) and C-terminal immunoglobulin (Ig)-like C1 domain. Missense mutations are depicted by gray circles. (B) Immunohistochemistry analysis of B2M in DLBCL biopsies (top panel) and cell lines (bottom panel) harboring missense mutant alleles. The exact type of alterations affecting each sample is indicated (Δ, deletion; M, mutation) (Scale = 100 µm). (C) Immunoblot analysis of B2M expression in WSU cells transduced with bicistronic lentiviral vectors expressing WT or missense variants of B2M, and blasticidin downstream of an IRES element (actin, loading control). The bar graph below shows the qRT-PCR quantification of the relative blasticidin mRNA levels (mean +/− SEM), which reflect the abundance of B2M transcripts, in the transduced cells.

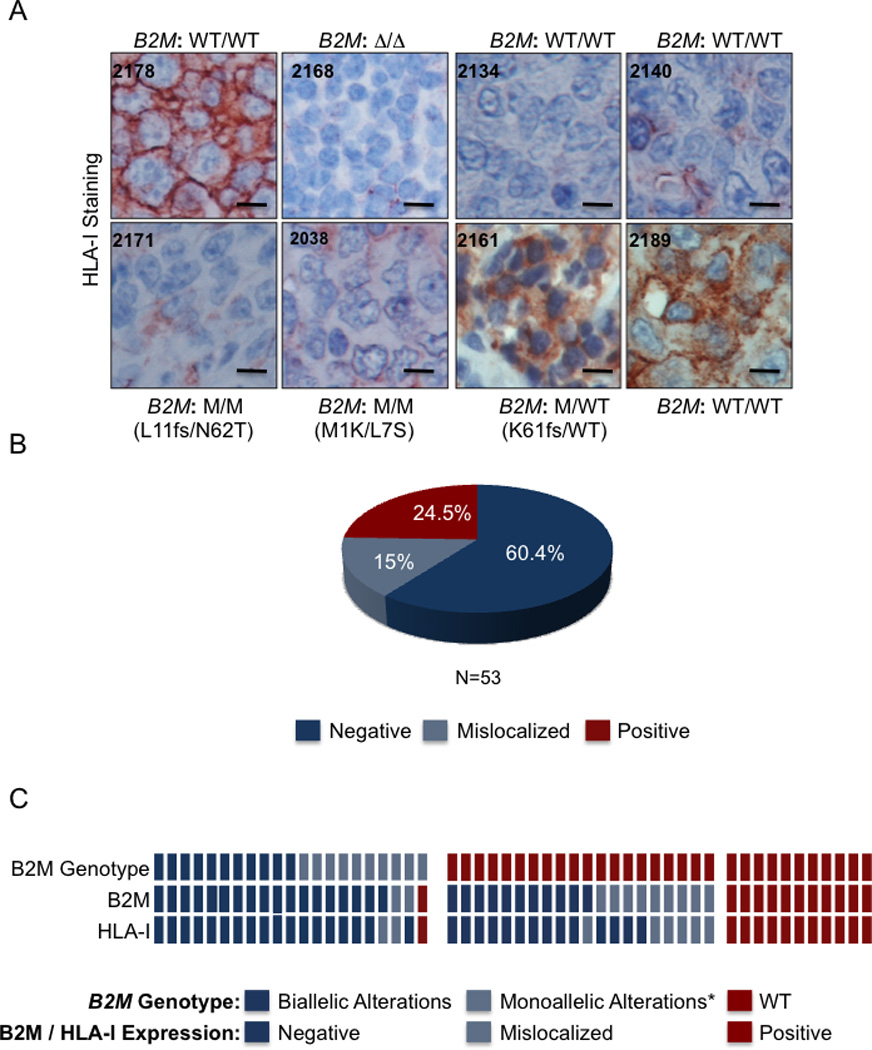

75% of DLBCL display aberrant B2M protein expression

To examine the functional consequences of B2M structural alterations, we analyzed B2M protein expression in normal lymphoid tissues, as well as in 53 DLBCL biopsies and 21 cell lines by IHC analysis. In normal B cells, including germinal-center (GC) B cells, B2M is predominantly expressed on the cell surface as part of the HLA-I complex (Figure S2). However, 75% of DLBCL samples either lacked B2M expression (n=29/53) or displayed a variety of aberrant expression patterns, including cytosolic (n=8/53) or peri-nuclear Golgi (n=3/53) localization (Figure 3A and 3B). While biopsies and cell lines with biallelic B2M gene alterations exhibit negative staining, as expected, a significant fraction of cases with monoallelic B2M inactivation (n=7/10) also displayed absent or mislocalized protein expression, suggesting silencing of the normal allele or the presence of alternative mechanisms of B2M inactivation by improper subcellular localization (Figure 3B–D and Table S2). Furthermore, eleven cases with normal B2M alleles were also negative for membrane B2M expression. Thus, the majority of DLBCL samples lack cell surface B2M.

Figure 3. Frequent loss of B2M protein expression in DLBCL.

(A) Immunohistochemistry analysis of B2M expression in DLBCL biopsies. Shown are representative examples for the different subcellular localization patterns: membrane (normal), peri-nuclear/Golgi (indicated by arrows), cytosolic, and no detectable staining (see also Table S2 and Figure S2). The genetic configuration of the two B2M alleles is indicated for each case (Scale = 100 µm). (B) Top panel: overall percentage of DLBCL primary biopsies showing absent (negative), mislocalized, or normal (membrane positive) B2M expression. Bottom panel: pie charts representing percent distribution of B2M expression, according to genotype. Note that the “monoallelic” cases also include 3 samples where the status of the second allele could not be determined. The total number of cases analyzed in each group is specified at the bottom. (C) Immunoblot analysis for B2M and tubulin (loading control) in DLBCL cell lines carrying WT or genetically altered B2M alleles, as indicated. (D) Immunohistochemistry analysis of B2M expression in representative DLBCL cell lines showing various subcellular distribution patterns. The status of the B2M locus is indicated (Scale = 100 µm).

Defects in B2M expression are associated with loss of cell-surface HLA-I expression

To investigate whether B2M genetic alterations result in perturbed cell surface HLA-I expression, we analyzed the same panel of DLBCL biopsies (n=53) by IHC using the HC-10 antibody, which recognizes HLA-I (A, B, C) (Stam et al., 1990). We observed positive, negative, or mislocalized HLA-I staining patterns, directly mirroring the pattern of B2M (Figure 4A and Figure 4B). In particular, all samples with normal cell-surface B2M expression show positive HLA-I staining (Figure 4C), while cases with mislocalized B2M protein (n=11) have either cytosolic or no HLA-I, indicating that the mechanisms responsible for the perturbation of the normal B2M sub-cellular localization can also affect the localization or stability of HLA-I proteins. The remaining 29 samples, which lack detectable B2M expression, exhibited negative staining for HLA-I, with the exception of two cases where the HLA-I protein was mislocalized. These observations confirm that loss of cell surface B2M expression, through genomic alterations or other yet uncharacterized mechanisms, is associated with lack of membrane HLA-I in DLBCL. Thus, overall, 75% (40/53) of DLBCL samples lack cell membrane HLA-I expression.

Figure 4. Defects in B2M expression associate with the lack of cell surface HLA-I.

(A) Immunohistochemistry analysis of HLA-I in DLBCL samples using the HC-10 antibody, which recognizes HLA-B and C. The genetic status of B2M is indicated for each sample (Scale = 100 µm). (B) Percentage distribution of DLBCL samples with negative, mislocalized, and positive cell surface expression of HLA-I. (C) Relationship between B2M genetic status and expression of the B2M and HLA-I proteins in DLBCL biopsies. In the heatmap, each column represents one DLBCL sample; the genotype and staining patterns are color-coded as indicated (* this category includes 3 mutated samples where the status of the second allele could not be determined).

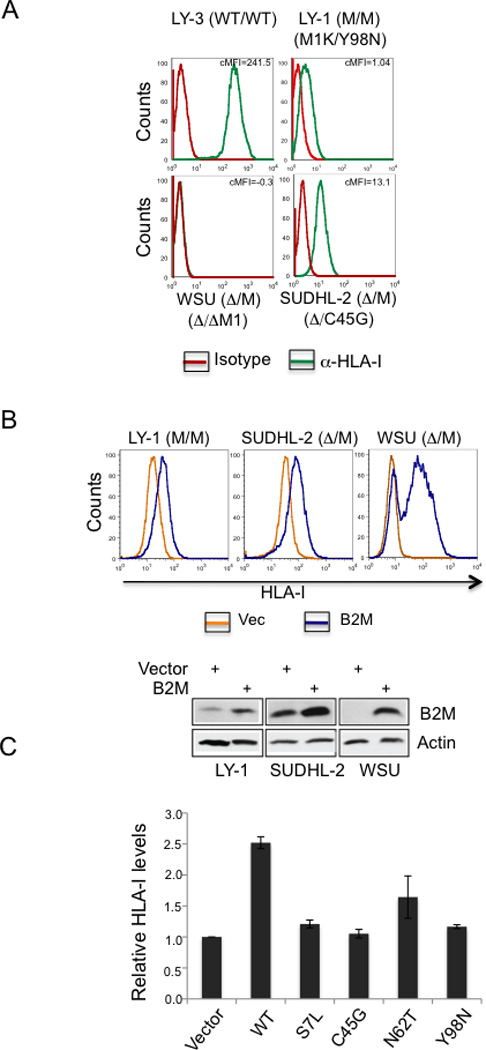

Re-expression of normal, but not mutant, B2M proteins results in restoration of cell surface HLA-I expression

To confirm that the loss of HLA-I is indeed caused by absent or mislocalized B2M expression, we designed experiments to reintroduce functional or missense B2M alleles in HLA-I negative DLBCL cell lines. These experiments were also intended to investigate whether lack of B2M expression had other effects on the transformed phenotype of DLBCL cells, as suggested by the proposed role of B2M in transducing the signal of the B cell receptor (BCR), a major survival and proliferation signal for B cells (Colonna et al., 1997; Takai, 2005). Flow cytometric analysis using the pan-HLA-I antibody W6/32 (Parham et al., 1979) showed that, similar to DLBCL biopsies, the cell lines with B2M homozygous alterations have significantly reduced (LY-1 and SUDHL2) or absent (WSU) cell-surface HLA-I expression (Figure 5A and Table S2). Transduction of these three cell lines with lentiviral vectors expressing wild-type B2M alleles led to either restoration (WSU) or a significant increase (LY-1 and SUDHL-2) in cell surface HLA-I expression (Figure 5B). Conversely, transduction of B2M missense mutants into WSU cells had no effects on HLA-I expression, thus confirming the non-functional nature of these mutants (Figure 5C). No other consequences on the transformed phenotype, including proliferation and survival, were observed (not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that B2M inactivation is the underlying cause for the lack of HLA-I plasma membrane localization in DLBCL.

Figure 5. Reintroduction of B2M WT, but not mutant alleles result in restoration of cell surface HLA-I.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface HLA-I expression in three DLBCL cell lines harboring biallelic B2M lesions, and a B2M wild-type cell line. The corrected mean fluorescence intensities (cMFI = HLA-I antibody MFI minus Isotype control MFI) are indicated. Note the complete lack of expression in WSU, and the significantly reduced levels in two additional cell lines carrying a B2M missense mutation with genetic loss of the second allele. (B) HLA-I expression in the three DLBCL cell lines upon reintroduction of WT B2M (blue), as compared to empty vector control (yellow). Western blot analysis of B2M expression in the same cells confirms the presence of exogenous B2M protein. Actin, loading control. (C) Relative cell surface HLA-I levels (mean +/− SEM), assessed by flow cytometry, in the WSU cell line reconstituted with vectors expressing WT or missense mutants of B2M, as compared to empty vector (arbitrarily set as 1).

Alterations inactivating the CD58 gene in DLBCL

The detection of recurrent copy number changes in CD58, a gene known to be involved in the adhesion and activation of most NK cells as well as CTLs, prompted the targeted sequencing of the CD58 coding exons in the same extended panel of 132 DLBCL samples. This analysis revealed a total of ten sequence variants, affecting 6.8% (n=9/132) of the samples (Figure 6A). Of these variants, 80% (n=8/10) are nonsense mutations, frameshift deletions/insertions or splice site mutations that result in aberrant transcripts encoding for truncated proteins, all of which lack the CD58 transmembrane domain (Figure S3A and Table S3). The remaining two variants were in-frame deletions, which result in the loss of either Tyr119 or Ser98 in the extracellular domain of CD58 (Figure 6A and Table S3), with presently unclear functional consequences. These mutations are distributed at comparable frequency in both GCB- and ABC/NC-DLBCL (6.2% and 7.5%, respectively) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. The CD58 gene is a target of genetic alterations in DLBCL.

(A) Schematic diagram of the CD58 gene (top) and protein (bottom), with its known functional domains (SP, signal peptide; Ig, Immunoglobulin single-pass type I membrane; TM, transmembrane; C, cytoplasmic). Color-coded symbols depict distinct types of mutations (see also Table S3). (B) Percentage of mutated biopsies and cell lines in the GCB and ABC/NC DLBCL subtypes. (C) dChip SNP inferred copy number heatmap of the 1p13.1 region encompassing CD58 in representative DLBCL cases and three normal (diploid) DNAs (see also Figure S3 and Table S3). (D) Percentage of samples harboring CD58 deletions in GCB and ABC/NC DLBCL subtypes. The actual number of samples over total analyzed is shown on top. (E) Overall frequency of CD58 structural alterations in DLBCL (Δ, deletion; M, mutation; nd, not determined).

High-density SNP array analysis revealed the presence of biallelic or monoallelic deletions affecting the CD58 locus in 19.8% of the samples analyzed (n=17/80 biopsies and 3/21 cell lines) (Figure 6C, Figure S3B and Table S3). Notably, the deleted regions in two samples encompass only the CD58 locus, strongly indicating that CD58 is the specific target of aberrations in this region (Figure S3B). Even though CD58 deletions were identified in both DLBCL phenotypic subtypes, their frequency was significantly higher in ABC/NC DLBCL, where they account for 30% (n=15/50) of samples, as compared to 9.8% (n=5/51) in GCB DLBCL (P < 0.01) (Figure 6D).

Based on the combined analysis of sequencing data and copy number data, 21.2% (n=28/132) of DLBCL samples harbor either biallelic (n=7/132, 5.3%) or monoallelic (n=21/132, 15.9%) genetic lesions disrupting the CD58 gene (Figure 6E). These alterations are more prevalent in ABC-DLBCLs (67.9% of the lesions found) than in GCB-DLBCLs (32.1%) (Figure S3C). Similar to B2M, PCR-amplified exon sequencing analysis of other mature B-NHLs failed to detect any mutation, suggesting that CD58 genetic lesions may be specifically selected during DLBCL pathogenesis.

Frequent loss of cell surface CD58 expression in DLBCL

Because DLBCL arises due to malignant transformation of germinal center (GC) B cells, we first sought to determine the expression pattern of CD58 in normal GC B cells. GEP analysis of purified tonsillar GC and naïve B cells, together with flow-cytometric analysis of reactive tonsils, confirmed that CD58 RNA and protein expression were high in GC B cells relative to naïve B cells (Figure S4A and B). Accordingly, immunofluorescence analysis of human tonsillar sections showed CD58 protein expression in GC B cells, but not in naïve B cells in the mantle zone (Figure S4C). In contrast to normal GC B cells, IHC analysis of DLBCL biopsies showed frequent negative or mislocalized protein expression (Figure 7A). Among the cases with biallelic alterations of CD58, 75% (n=3/4) exhibited no protein expression (Figure 7B and Table S4); the remaining sample, which harbors biallelic truncating mutations, showed an abnormal cytosolic localization pattern in the absence of membrane staining, probably due to the expression of proteins lacking the transmembrane domain, but which can be nonetheless recognized by the polyclonal CD58 antibody. Interestingly, 87% of the monoallelic and 54% of the WT samples also showed negative or mislocalized CD58 staining patterns, strongly suggesting alternative pathogenic mechanisms for CD58 inactivation. As in the primary biopsies, lack of surface CD58 protein expression was observed in all of the DLBCL cell lines harboring biallelic alterations (Figure S4D–E, Table S4).

Figure 7. Aberrant expression of the CD58 protein in DLBCL affects NK cell-mediated cytolysis.

(A) CD58 protein expression in representative DLBCL biopsies (genomic status as indicated: Δ, deletion; M, mutated; WT, wild type) (see also Table S4) (Scale = 100 µm). (B) Overall proportion of DLBCL biopsies showing defective CD58 surface expression (top). The relationship between CD58 genetic lesions and protein expression pattern in individual cases is presented below (* this category includes 5 mutated samples where the status of the second allele could not be determined). (C) Frequency of cases showing aberrant CD58 surface expression in DLBCL subtypes. (D) Percent NK cell-mediated cytolysis of HBL1 cells transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing CD58 (or empty vectors) at various effector to target (E:T) ratios (mean +/− SD; *, p < 0.001). Data shown represents one of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (see also Figure S4). (E) NK cell mediated cytolysis in the DLBCL cell line RIVA (WT for CD58) after blocking cell surface CD58 by anti-CD58 TS2/9 antibodies (mean +/− SD; *, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01). Data shown represents one of two experiments performed in triplicate (see also Figure S4).

Overall 67% of DLBCL biopsies and 19% of DLBCL cell lines lack CD58 cell surface expression. Despite the presence of significantly more frequent genetic alterations in ABC/NC-DLBCL, the percentage of cases showing absent or aberrant CD58 expression was similar in the two subtypes (GCB-DLBCL, 65%; ABC/NC-DLBCL, 68%) (Figure 7C and Figure S3C). Thus, loss of CD58 surface protein expression is a frequent event across all DLBCLs.

CD58 contributes to NK cell mediated cytolysis of DLBCL

To determine whether CD58 loss affects NK cell mediated lysis in DLBCL, we reintroduced the CD58 gene (long isoform), or control empty vectors, into the HBL1 DLBCL cell line, which harbors a homozygous deletion of the CD58 locus and hence lacks CD58 expression. Reconstituted HBL1 cells were then tested as targets in NK-mediated cytotoxicity assays. As shown in Figure 7D, re-expression of CD58 induced a significant increase in the percentage of cytolysis (30–50%, p < 0.001), when compared to vector-transduced cells. Conversely, blocking cell surface CD58 with the anti-CD58 TS2/9 antibody (Le et al., 1990) in the RIVA cell line, which expresses CD58, decreased the susceptibility to NK lysis by 20–26% (p < 0.001) (Figure 7E and Figure S4F,G), while TS2/9 had no effect on the the CD58-null HBL1 cell line (Figure S4H). Together, these data demonstrate that CD58 loss is involved the recognition of DLBCL by NK cells.

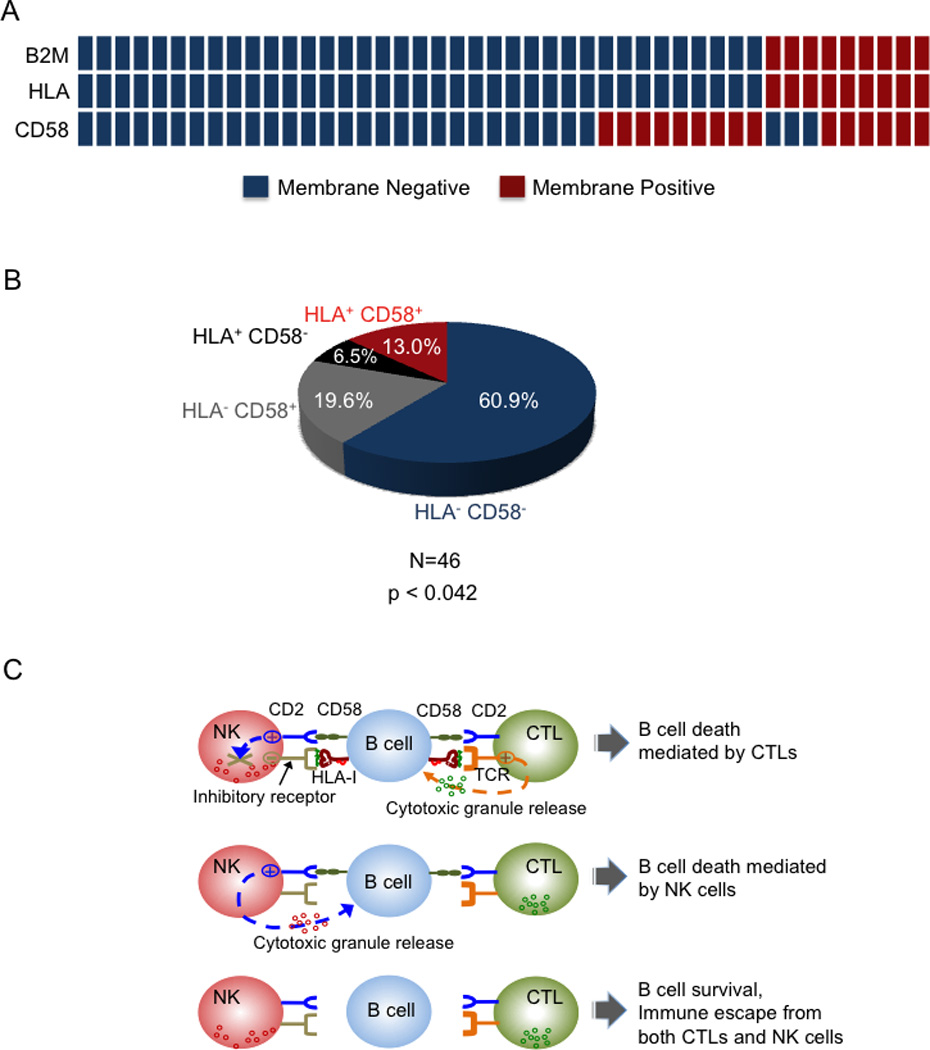

Most DLBCL cases lack expression of both HLA class I and CD58 proteins

Effective evasion of immune surveillance requires avoidance of both CTL and NK cell recognition. Therefore, it is conceivable that tumors would evolve to lose both HLA-I and CD58 and thus escape the recognition by both arms of cellular immunity. Consistent with this notion, 61% of the DLBCL cases analyzed concurrently lack HLA-I and CD58 on the cell surface (Figure 8A, B) (p < 0.042), suggesting that these alterations may be co-selected during lymphomagenesis for their complementary roles in protecting from CTL- and NK cell-mediated lysis.

Figure 8. Concurrent loss of cell surface HLA-I and CD58 is a common feature in DLBCL.

(A) Distribution of B2M, HLA-I and CD58 membrane protein expression in DLBCL. Columns represent individual DLBCL patients, with color codes indicating the presence or absence of surface B2M, HLA-I, and CD58 protein. (B) Overall proportion of DLBCL biopsies showing lack of HLA-I and CD58 surface protein expression. A two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to determine whether the correlation in the expression patterns of HLA-I and CD58 was statistically significant across individual DLBCL patients. C) Model for the mechanism of immune escape in DLBCL. Lymphoma cells displaying tumor-associated antigens through HLA-I are recognized and subsequently lysed by CTLs. To evade CTL recognition, tumors often downregulate HLA-I expression (top). However, HLA-I also acts as a ligand for the NK cell inhibitory receptors that transduce signals to counterbalance the activating cues from receptors such as CD2. Thus, tumor cells devoid of HLA-I are vulnerable to NK cell attack due to activation of NK cell CD2 by tumor cell CD58 (middle). In DLBCL, concurrent loss of HLA-I and CD58 confers protection from both T and NK cell mediated lysis (bottom).

DISCUSSION

B2M and CD58 gene inactivation in DLBCL

Our results indicate that direct inactivation of the B2M gene by deletion and/or mutation occurs in a sizable fraction of DLBCLs. B2M inactivation, whether biallelic or monoallelic, is often associated with loss of protein expression. The type and distribution of these lesions are analogous to those occasionally found in melanoma (Hicklin et al., 1998) and cervical carcinoma (Koopman et al., 2000). In addition, B2M genetic lesions have been previously reported in a small number of DLBCL cases originating from the testis or the central nervous system (n=2 of 15 analyzed) (Jordanova et al., 2003) and in the Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line Daudi (Rosa et al., 1983). Our results show that B2M gene inactivation is a recurrent event in nodal DLBCLs of both the GCB- and ABC-type, suggesting a pathogenetic role in this disease (see below).

Inactivation of the CD58 gene by structural alterations had not been previously appreciated in DLBCL and has not been reported in other types of cancer. These lesions include truncating mutations and focal deletions, often disrupting both alleles, and affect 21% of DLBCL cases. As in the case of B2M, CD58 lesions can be found in both major subtypes of DLBCL. Notably, we observed B2M and CD58 mutations in DLBCL, but not in other common types of lymphoid malignancies derived from mature B cells, suggesting that they represent pathogenetic mechanisms rather specific for this type of tumor.

Additional mechanisms lead to the lack of functional B2M and CD58 protein expression in DLBCL

A notable finding of this study is that direct genetic lesions of the B2M and CD58 genes represent only “the tip of the iceberg” of heterogeneous defects in the production of functional B2M and CD58 polypeptides in DLBCL. In fact, additional mechanisms lead to the complete lack of cell surface expression of these molecules in over half of DLBCL cases. These mechanisms include the lack of expression of the second allele in cases with monoallelic gene inactivation, which is commonly observed in tumor suppressor genes and may be a consequence of promoter hypermethylation or other epigenetic mechanisms. More unexpected was the finding of mislocalized protein expression in cases with either monoallelic gene inactivation or wild-type alleles, observed for both B2M and CD58. The basis for this functional alteration is unknown, and may involve yet unidentified genetic lesions affecting proteins that participate in the intracellular transport of B2M and CD58. B2M mislocalization may also be due to defects in HLA-I expression or assembly, which is required for cell surface localization of B2M (Hughes et al., 1997). However, no recurrent gene copy number alterations, mutations or abnormalities in RNA expression were detected in any of the candidate genes involved in this process, including TAP1, TAP2, LMP2, and LMP7. Thus, the identification of the mechanisms leading to mislocalized B2M and CD58 expression will require further genomic and/or functional screenings.

Loss of functional B2M leads to lack of HLA-I expression and escape from CTL

As expected, all cases lacking B2M cell surface expression were also devoid of membrane HLA-I, independent of the mechanism underlying the B2M defect (in total, 75% of all DLBCLs). Since HLA-1 is misfolded and subsequently degraded in the absence of functional B2M (Hughes et al., 1997), the lack of HLA-I expression in these cases represents a consequence of B2M defects. Consistent with this notion, restoration of B2M expression in B2M-null cell lines led to re-expression of HLA-I. In rare cases, where the HLA-I protein is absent while the B2M protein is mislocalized, the defects may reside in the HLA-I heavy chain genes or in the transport machinery, since both are required for proper B2M localization (Hughes et al., 1997; Peaper and Cresswell, 2008). Indeed, deletions of various portions of the HLA-I locus have been reported in DLBCL (Riemersma et al., 2000), although direct evidence for the specific targeting of HLA-I genes is missing. Overall, our results provide a genetic basis and a mechanistic explanation to previous observations on the lack of HLA-I expression in DLBCL.

The HLA-I complex presents antigenic peptides to CTL, which then proceed to the destruction of the target cells. Thus, HLA-I negative DLBCL cells will be unable to present such peptides, and will remain invisible to T-cell mediated immune-surveillance. The nature of the antigenic peptides that DLBCL cells fail to present is unknown. Since these cases are not infected by any known viruses, the involved antigens may be represented by “tumor antigens” generated by the deregulated expression of proteins or by mutant protein themselves (Boon and van der Bruggen, 1996).

Lack of CD58 is relevant for recognition by both CTL and NK cells

By acting as a ligand for the CD2 receptor on T- and NK-cells, CD58 contributes to the adhesion and activation of both these types of immune effector cells. Accordingly, monoclonal antibodies against CD58, which disrupt CD2/CD58 interactions, result in diminished recognition and cytolysis of target cells by both CTLs and NK cells (Altomonte et al., 1993; Gwin et al., 1996; Sanchez-Madrid et al., 1982). The relevance of CD58 in tumorigenesis has been previously suggested based on the observation that CD58 expression is downregulated in several cancer types, although the underlying mechanisms are unknown. The results herein confirm that variations in CD58 expression levels can influence NK cell-mediated cytolysis of DLBCL cells in vitro (Figure 7D), and suggest that loss of CD58 expression may contribute to decreased recognition of DLBCL cells by NK cells in vivo.

Frequent combined loss of HLA-I and CD58 suggests co-selection during lymphomagenesis

While the lack of HLA-I expression in the majority of DLBCL samples confers escape from CTL, the same event will trigger recognition and lysis by NK cells (Karre et al., 1986), an event unlikely to be positively selected during lymphomagenesis. This paradox could be explained by the observation that DLBCLs often concomitantly lose the expression of CD58, which may contribute to their escape from both CTL and NK recognition (summarized in Figure 8C). In support of this notion, 75.7% of the DLBCL cases lacking HLA-I expression also lack CD58 expression. The significant association between these two events suggests that they may be co-selected during lymphomagenesis for their combined role in the escape from immune recognition.

Implications for DLBCL pathogenesis and therapy

The findings herein indicate that escape from recognition by immune effector cells may represent a frequent pathogenetic event in DLBCL, common to both the GCB and ABC subtypes. This mechanism is likely to be an important contributor to the development of DLBCL by complementing the defects in proliferation, differentiation and survival that are caused by other genetic lesions present in these tumors. Alterations affecting other molecules involved in immune recognition, such as the T-cell-recognition ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 as well as the transcriptional coactivator CIITA have been reported in PMBCL (Green et al., 2010; Steidl et al., 2011). These data further corroborate the hypothesis that escape from immune-surveillance through multiple mechanisms is a common feature of all DLBCL subtypes. Evasion from the immune system may protect DLBCL cells from the recognition of altered polypeptides produced by mutated oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (Boon and van der Bruggen, 1996). The ability to escape from both the adaptive and innate immune responses should be considered in the development of immunotherapeutic approaches for DLBCL.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Primary samples

Primary biopsies from 111 newly diagnosed, previously untreated DLBCL patients were obtained as paraffin-embedded and/or frozen material from the archives of the Departments of Pathology at Columbia University and Weill Cornell Medical College, after approval by the respective Institutional Review Boards (Exempt Human Subject Research of anonymized/deidentified existing pathological specimens, under regulatory guideline 45 CFR 46.101(b)(4)) and their detailed characterization has been reported (Compagno et al., Nature 2009). Based on prior gene expression profile studies, the DLBCL cohort (cell lines and primary biopsies) comprised of 65 GCB-DLBCL and 67 ABC/non-classified (NC) cases. Other B-NHL cases analyzed included 37 Follicular Lymphoma, 44 Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, 16 Burkitt’s Lymphoma and 11 Marginal Zone Lymphoma.

Mutation Analysis

Targeted DNA sequencing of the B2M and CD58 coding exons was performed by the Sanger method on PCR products obtained from whole genome amplified DNA (RepliG kit, Qiagen). The somatic mutations identified through this method were further confirmed by PCR amplification and double-strand DNA sequencing of independent products obtained from high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. The sequencing results were compared to the UCSC Human Genome database reference mRNA sequence with accession number NM_004048.2 for B2M and NM_001779 for CD58, using the Mutation Surveyor software as described (Pasqualucci et al., Nature Genetics 2011b). In cases with more than one mutation, allelic distribution was analyzed by cloning and sequencing of PCR products encompassing both sequence variants, obtained from cDNA and/or high molecular weight genomic DNA. The PCR primers used for genomic and cDNA amplification of B2M and CD58 are listed in supplementary experimental procedures.

High-density SNP array analysis

Genome-wide DNA profiles of 80 DLBCL primary cases and 11 paired normal DNAs were obtained using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as part of an independent study (Pasqualucci et al., 2011b) and are available from the dbGaP repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap) under accession number phs000328.v1.p1. Copy number data for the DLBCL cell lines were obtained from the GEO database (Accession number GSE22208). The detailed procedure for data processing and analysis is described in Pasqualucci et al., 2011b.

Flow Cytometry

Analysis of cell surface HLA-I in DLBCL cell lines was performed using the W6/32-FITC antibody (Abcam) (Parham et al., 1979). Cells were washed twice for 5 minutes in PBS+0.5% BSA and incubated with 1 µg of W6/32-FITC per million cells, resuspended in 100 µl of PBS+0.5% BSA, for 30 minutes on ice. The unbound antibody was removed by washing the cells twice with PBS+0.5% BSA for 5 minutes followed by analysis on the FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). The data was analyzed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo softwares (TreeStar). Corrected mean fluorescence intensities (cMFIs) were calculated by subtracting the MFI of the W6/32-FITC labeled cells from that of isotype control. Similarly, cell surface CD58 is assessed using CD58-PE (AICD58, Beckman Coulter).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin embedded DLBCL tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed as described (Compagno et al, 2009) and analyzed for B2M, HLA-I heavy chain (HC) and CD58 protein expression by immunohistochemistry using standard protocols. Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave. The sections were incubated with anti-B2M (1:2000, DAKO), HC-10 (1:100, a generous gift from Dr. J. Neefjes, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam) (Stam et al., 1990), or anti-CD58 antibody (5 µg/mL, R&D Systems, AF1689) overnight. For B2M and HLA-I HC, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (EnVision, Dako) followed by visualization with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma). For CD58, the sections were incubated with donkey anti-goat-biotin secondary antibody (1:100, Jackson Immuno) followed by streptavidin-HRP (1:100, Vector Lab), which was then visualized by 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Lab). All sections with more than 20% of tumor cells were considered for scoring.

Lentiviral Transductions

For the reconstitution studies, lentiviral vectors encoding B2M and CD58 were generated by replacing the GFP cassette of the pCCL.sin.PPT.hPGK.GFPWpre vector (kindly provided by Dr. Luigi Naldini, Fondazione San Raffaele, Italy, (Dull et al., 1998)) with a B2M- or CD58-IRES-Blasticidin cassette, respectively. Lentiviral vectors, along with helper plasmids encoding Δ8.91 and the VSV-G envelope glycoprotein, were co-transfected into HEK-293 cells, and the viral supernatant was then used to infect DLBCL cell lines according to standard protocols. In the B2M reconstitution experiments, transduced cells were selected in Blasticidin (LY-1, 5 µg/mL; WSU, 1 µg/mL; SUDHL-2, 0.5 µg/mL) for 10 days before analysis. For the NK-mediated cytotoxicity assays, HBL1 cells were used five days after transduction with CD58-expressing vectors, in the absence of selection.

Immunoblotting

The expression of B2M and CD58 in DLBCL cell lines was analyzed by standard immunoblotting protocols, using anti-B2M (Dako, 1:1000) and anti-CD58 (AF1689, R&D Systems: 1:500; for the glycosylated form, TS2/9, Biolegend: 1:200) (Le et al., 1990) specific antibodies. As loading controls, the levels of β-actin (1:10000, Clone AC-15; Sigma) or β-tubulin (1:2000, Clone B-5-1-2; Sigma) were analyzed.

NK cell isolation and cytotoxicity assays

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from freshly collected buffy coats (New York Blood Center) of healthy donors by Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation. NK cells were isolated from PBMCs using the NK Cell Isolation Kit (130-092-657, Miltenyi Biotec), and were maintained in Iscove’s medium containing 5% FCS, 10% human AB serum (New York Blood Center), minimal essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, L-glutamine, and 2.5U/ml of recombinant human IL-2 (PeproTech) for 12 hours. For cytotoxicity assays, target DLBCL cell lines (HBL-1 and RIVA) either untransduced or transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing CD58 were first labeled with 2.5 µM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Invitrogen) for 24 hours. Target cells (T) (0.1 × 106) were then incubated with effector NK (E) cells at a ratio (E:T) of 0:1, 1.25:1, 2.5:1, and 5:1 for 4 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the percentage of cell death in the CFSE-labeled target cells was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) uptake. NK cell mediated cytoxicity was measured by subtracting the background cell death (E:T=0:1). For the CD58-blocking experiments, RIVA or HBL1 cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour with either the anti-CD58 TS2/9 or an isotype control antibody (both from Biolegend; final concentration, 10 µg/ml per million cells). The blocking efficiency was assessed by staining the cells with the anti-CD58 TS2/9-APC antibody (Biolegend) followed by flow cytometric analysis.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Disruption of B2M and CD58 by genetic lesions is a frequent event in DLBCL

Multiple mechanisms lead to combined loss of surface B2M, HLA-I and CD58 expression

Evasion of immune surveillance plays a central role in DLBCL pathogenesis

SIGNIFICANCE.

DLBCL is the most common type of lymphoma and includes several subtypes with distinct genotypic, phenotypic and clinical features. We report that the majority of cases, including the two major subtypes, fail to express B2M and CD58. These two molecules are involved in the immune recognition of tumor cells by two important arms of cellular immunity, namely CTL and NK cells. The frequency of these defects, the heterogeneity of the involved mechanisms, including direct gene inactivation, and the significant co-occurrence of defects leading to the immune-escape from both CTL and NK cells, all suggest a strong selective pressure during lymphomagenesis. Overall, these findings implicate the evasion of immune-recognition as an important component of DLBCL pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Q. Shen for the TMA staining; V.A. Wells, A. Grunn, G. Fabbri and M. Messina for help with sequencing and copy number analysis; C.G. Mullighan and J. Ma for the initial characterization of the DLBCL copy number data; R. Rabadan and V. Trifonov for contributing to the initial identification of B2M mutations; J. Neefjes for the HC-10 antibody; L. Naldini for the pCCL.sin.PPT.hPGK.GFPWpre lentiviral vector; and G. Gaidano and R. Maute for critical reading of the manuscript. Automated DNA sequencing was performed at Genewiz.Inc. This work was supported by N.I.H. Grants PO1-CA092625 and RO1-CA37295 (to R.D.-F.) and a Specialized Center of Research grant from the Leukemia &Lymphoma Society (to R.D.-F.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession number. The SNP Array 6.0 data reported in this paper have been deposited in dbGaP under accession no. phs000328.v1.p1. Gene expression profile data from the DLBCL primary cases are available from the GEO database under accession no. GSE12195.

Accession codes. The SNP Array 6.0 data reported in this paper have been deposited in dbGaP under accession no. phs000328.v1.p1.

REFERENCES

- Abramson JS, Shipp MA. Advances in the biology and therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: moving toward a molecularly targeted approach. Blood. 2005;106:1164–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomonte M, Gloghini A, Bertola G, Gasparollo A, Carbone A, Ferrone S, Maio M. Differential expression of cell adhesion molecules CD54/CD11a and CD58/CD2 by human melanoma cells and functional role in their interaction with cytotoxic cells. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3343–3348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billaud M, Rousset F, Calender A, Cordier M, Aubry JP, Laisse V, Lenoir GM. Low expression of lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1 and LFA-3 adhesion molecules is a common trait in Burkitt's lymphoma associated with and not associated with Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1990;75:1827–1833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman PJ, Saper MA, Samraoui B, Bennett WS, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Structure of the human class I histocompatibility antigen, HLA-A2. Nature. 1987;329:506–512. doi: 10.1038/329506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis RL, Roozemond RC, van de Griend RJ. Induction and blocking of cytolysis in CD2+, CD3− NK and CD2+, CD3+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes via CD2 50 KD sheep erythrocyte receptor. J Immunol. 1986;136:3939–3944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon T, van der Bruggen P. Human tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:725–729. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Navarro F, Bellon T, Llano M, Garcia P, Samaridis J, Angman L, Cella M, Lopez-Botet M. A common inhibitory receptor for major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on human lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagno M, Lim WK, Grunn A, Nandula SV, Brahmachary M, Shen Q, Bertoni F, Ponzoni M, Scandurra M, Califano A. Mutations of multiple genes cause deregulation of NF-kappaB in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2009;459:717–721. doi: 10.1038/nature07968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, Romesser PB, Kohlhammer H, Lamy L, Zhao H, Yang Y, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;463:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML, Selvaraj P, Mattaliano RJ, Springer TA. Anchoring mechanisms for LFA-3 cell adhesion glycoprotein at membrane surface. Nature. 1987;329:846–848. doi: 10.1038/329846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido F, Cabrera T, Aptsiauri N. "Hard" and "soft" lesions underlying the HLA class I alterations in cancer cells: implications for immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:249–256. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, Juszczynski P, Currie T, O'Donnell E, Chapuy B, Takeyama K, Neuberg D, Golub TR, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:3268–3277. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwin JL, Gercel-Taylor C, Taylor DD, Eisenberg B. Role of LFA-3, ICAM-1, and MHC class I on the sensitivity of human tumor cells to LAK cells. J Surg Res. 1996;60:129–136. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicklin DJ, Wang Z, Arienti F, Rivoltini L, Parmiani G, Ferrone S. beta2-Microglobulin mutations, HLA class I antigen loss, and tumor progression in melanoma. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2720–2729. doi: 10.1172/JCI498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JZ, Sanger WG, Greiner TC, Staudt LM, Weisenburger DD, Pickering DL, Lynch JC, Armitage JO, Warnke RA, Alizadeh AA, et al. The t(14;18) defines a unique subset of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a germinal center B-cell gene expression profile. Blood. 2002;99:2285–2290. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EA, Hammond C, Cresswell P. Misfolded major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains are translocated into the cytoplasm and degraded by the proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1896–1901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal J, Greiner TC, Patel K, Dave BJ, Smith L, Ji J, Wright G, Sanger WG, Pickering DL, Jain S, et al. Distinctive patterns of BCL6 molecular alterations and their functional consequences in different subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2007;21:2332–2343. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordanova ES, Riemersma SA, Philippo K, Schuuring E, Kluin PM. Beta2-microglobulin aberrations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the testis and the central nervous system. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:393–398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner SB, Damle NK, Blake J, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA. CD2/LFA-3 ligation induces phospholipase-C gamma 1 tyrosine phosphorylation and regulates CD3 signaling. J Immunol. 1992;148:2023–2029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karre K, Ljunggren HG, Piontek G, Kiessling R. Selective rejection of H-2-deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defence strategy. Nature. 1986;319:675–678. doi: 10.1038/319675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U, Dalla-Favera R. Germinal centres: role in B-cell physiology and malignancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:22–33. doi: 10.1038/nri2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman LA, Corver WE, van der Slik AR, Giphart MJ, Fleuren GJ. Multiple genetic alterations cause frequent and heterogeneous human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen class I loss in cervical cancer. J Exp Med. 2000;191:961–976. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le PT, Vollger LW, Haynes BF, Singer KH. Ligand binding to the LFA-3 cell adhesion molecule induces IL-1 production by human thymic epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:4541–4547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lam L, George TC, Wright GW, Dave SS, Zhao H, Xu W, Rosenwald A, et al. Oncogenic CARD11 mutations in human diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Science. 2008;319:1676–1679. doi: 10.1126/science.1153629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Staudt LM. Aggressive lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1417–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0807082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum J, Bhagat G, Tang H, Mo T, Brahmachary M, Shen Q, Chadburn A, Rajewsky K, Tarakhovsky A, Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R. BLIMP1 is a tumor suppressor gene frequently disrupted in activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:568–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Mungall AJ, An J, Goya R, Paul JE, Boyle M, Woolcock BW, Kuchenbauer F, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Chiu R, Field M, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Chiu R, Field M, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Lim KH, Kohlhammer H, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhao H, et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature. 2010;470:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature09671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham P, Barnstable CJ, Bodmer WF. Use of a monoclonal antibody (W6/32) in structural studies of HLA-A,B,C, antigens. J Immunol. 1979;123:342–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Compagno M, Houldsworth J, Monti S, Grunn A, Nandula SV, Aster JC, Murty VV, Shipp MA, Dalla-Favera R. Inactivation of the PRDM1/BLIMP1 gene in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:311–317. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Dominguez-Sola D, Chiarenza A, Fabbri G, Grunn A, Trifonov V, Kasper LH, Lerach S, Tang H, Ma J, et al. Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2011a;471:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature09730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Migliazza A, Basso K, Houldsworth J, Chaganti RS, Dalla-Favera R. Mutations of the BCL6 proto-oncogene disrupt its negative autoregulation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:2914–2923. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Trifonov V, Fabbri G, Ma J, Rossi D, Chiarenza A, Wells VA, Grunn A, Messina M, Elliot O, et al. Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2011b;43:830–837. doi: 10.1038/ng.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaper DR, Cresswell P. Regulation of MHC class I assembly and peptide binding. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:343–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemersma SA, Jordanova ES, Schop RF, Philippo K, Looijenga LH, Schuuring E, Kluin PM. Extensive genetic alterations of the HLA region, including homozygous deletions of HLA class II genes in B-cell lymphomas arising in immune-privileged sites. Blood. 2000;96:3569–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa F, Berissi H, Weissenbach J, Maroteaux L, Fellous M, Revel M. The beta2-microglobulin mRNA in human Daudi cells has a mutated initiation codon but is still inducible by interferon. EMBO J. 1983;2:239–243. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Madrid F, Krensky AM, Ware CF, Robbins E, Strominger JL, Burakoff SJ, Springer TA. Three distinct antigens associated with human T-lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis: LFA-1, LFA-2, and LFA-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7489–7493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA, Dustin ML, Kishimoto TK, Marlin SD. The lymphocyte function-associated LFA-1, CD2, and LFA-3 molecules: cell adhesion receptors of the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1987;5:223–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.05.040187.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam NJ, Vroom TM, Peters PJ, Pastoors EB, Ploegh HL. HLA-A- and HLA-B-specific monoclonal antibodies reactive with free heavy chains in western blots, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and in cryo-immuno-electron microscopy. Int Immunol. 1990;2:113–125. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt LM, Dave S. The biology of human lymphoid malignancies revealed by gene expression profiling. Adv Immunol. 2005;87:163–208. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)87005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl C, Shah SP, Woolcock BW, Rui L, Kawahara M, Farinha P, Johnson NA, Zhao Y, Telenius A, Neriah SB, et al. MHC class II transactivator CIITA is a recurrent gene fusion partner in lymphoid cancers. Nature. 2011;471:377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature09754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, Lathe W, 3rd, Kondrashov AS, Bork P. Prediction of deleterious human alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:591–597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T. Paired immunoglobulin-like receptors and their MHC class I recognition. Immunology. 2005;115:433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend AR, Gotch FM, Davey J. Cytotoxic T cells recognize fragments of the influenza nucleoprotein. Cell. 1985;42:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Smolyar A, Tan K, Liu JH, Kim M, Sun ZY, Wagner G, Reinherz EL. Structure of a heterophilic adhesion complex between the human CD2 and CD58 (LFA-3) counterreceptors. Cell. 1999;97:791–803. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye BH, Lista F, Lo Coco F, Knowles DM, Offit K, Chaganti RS, Dalla-Favera R. Alterations of a zinc finger-encoding gene, BCL-6, in diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Science. 1993;262:747–750. doi: 10.1126/science.8235596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Immunological surveillance against altered self components by sensitised T lymphocytes in lymphocytic choriomeningitis. Nature. 1974;251:547–548. doi: 10.1038/251547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.