Abstract

Summary: The prioritization of candidate disease genes is often based on integrated datasets and their network representation with genes as nodes connected by edges for biological relationships. However, the majority of prioritization methods does not allow for a straightforward integration of the user’s own input data. Therefore, we developed the Cytoscape plugin NetworkPrioritizer that particularly supports the integrative network-based prioritization of candidate disease genes or other molecules. Our versatile software tool computes a number of important centrality measures to rank nodes based on their relevance for network connectivity and provides different methods to aggregate and compare rankings.

Availability: NetworkPrioritizer and the online documentation are freely available at http://www.networkprioritizer.de.

Contact: mario.albrecht@mpi-inf.mpg.de

1 INTRODUCTION

An important objective of medical bioinformatics is to elucidate the genetic foundations of human diseases. To this end, it is crucial to identify genes that might predispose to or cause specific diseases. To rank candidate genes, e.g. from some genome-wide association study, according to their disease relevance, the existing plethora of computational prioritization methods exploits the available biomedical knowledge. Many methods combine multiple genotypic and phenotypic data sources, e.g. gene expression, protein interactions and overlapping disease characteristics (Doncheva et al., 2012a). Integrated information of biological and molecular relationships and interactions is naturally represented as networks. The biological connections between known disease genes and the remaining genes in a network are of particular interest, as they can point to new disease genes according to the guilt-by-association principle.

The majority of prioritization methods are available only as web services (Tranchevent et al., 2010). Since these require the upload of the user’s input data, they do not allow for the analysis of confidential data. Furthermore, most web services rely on pre-defined background data. For example, GeneWanderer ranks candidate genes based on their distance to disease genes in a pre-defined protein–protein interaction network. GeneDistiller and ENDEAVOUR combine multiple data sources, but do not allow the user to include own data. Additionally, the rank aggregation used by ENDEAVOUR cannot be modified by the user. Existing Cytoscape plugins for prioritization tasks are also subject to major limitations. The plugin iCTNet (Wang et al., 2011) queries only a specific database to construct networks, but a straightforward integration of own data is not possible. The plugins cytoHubba (Lin et al., 2008) and GPEC (Le and Kwon, 2012) rank network nodes using their close neighborhood and random walks in the network, respectively. However, neither one supports multiple rankings or further analysis of the rankings. The plugin NetworkAnalyzer (Assenov et al., 2008; Doncheva et al., 2012b) and the Java application CentiBiN (Junker et al., 2006) feature a large set of centrality measures, but they cannot compute the measures for a user-defined set of seed nodes or for weighted networks.

Here, we present NetworkPrioritizer, a novel Cytoscape plugin for the integrative network-based prioritization of candidate genes or other molecules. It comprises two main functionalities. First, it facilitates the estimation of the relevance of network nodes, e.g. candidate genes, with regard to a set of seed nodes, e.g. known disease genes. Second, our plugin allows for the user-guided aggregation and comparison of multiple node rankings derived according to different relevance measures. Users can supply their own data and tailor the network analysis as well as the rank aggregation to their needs.

2 SOFTWARE FEATURES

2.1 Relevance measures and ranking

NetworkPrioritizer can rank nodes in any user-imported Cytoscape network. Each ranking is based on the relevance of nodes for the network connectivity. This relevance is estimated by a number of centrality measures such as shortest path betweenness, shortest path closeness, random walk betweenness, random walk receiver closeness and random walk transmitter closeness (Borgatti, 2005) (see web site). Closeness quantifies the path distance between a node and the rest of the network. Betweenness measures the influence of a node on the network paths connecting other nodes. Since these measures are applicable only to undirected networks, the edge directions are ignored in directed networks.

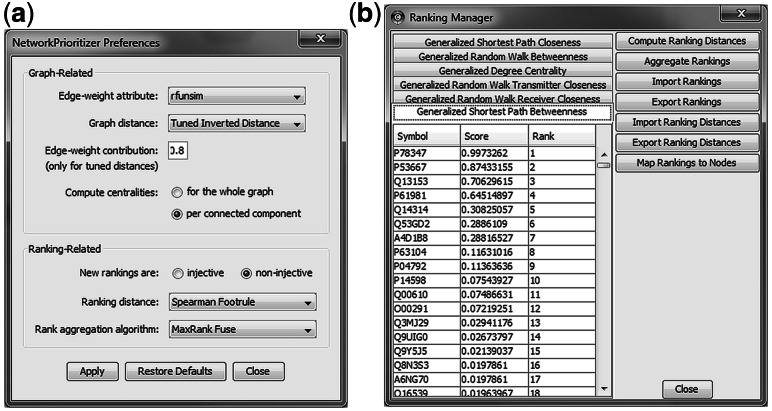

NetworkPrioritizer can handle unweighted and weighted networks with user-adjustable effect of the edge weights on the computed centralities (Opsahl et al., 2010) (Fig. 1a). A particular feature of NetworkPrioritizer is the computation of the centrality measures for a set of seed nodes, which can be imported from a text file or selected in the network view.

Fig. 1.

Two important user-interface elements of NetworkPrioritizer. (a) In the Preferences dialog, the user can adjust settings for the network analysis and for the rank aggregation. (b) The Ranking Manager allows to inspect, compare, aggregate, export and import rankings

2.2 Rank aggregation

The Ranking Manager of NetworkPrioritizer provides different methods to aggregate and compare multiple rankings (Fig. 1b). In this context, the rankings to aggregate are called primary rankings.

Weighted Borda Fuse (WBF) is a generalization of the popular Borda count aggregation method (Saari, 1999), which works as follows: In primary rankings, each node receives a score that is equal to the number of nodes ranked lower in the respective primary ranking. In the aggregated ranking, the nodes are ranked according to the sum of their sores. WBF also allows weighing the contribution of each primary ranking to the aggregated score.

Weighted AddScore Fuse (WASF) calculates the weighted sum of scores for each node in the primary rankings and awards a higher rank the larger this sum is. Since both WBF and WASF are consensus-based aggregation methods, they can be used to identify candidate genes that attain high ranks in all primary rankings. If the primary rankings are based on comparable scores, i.e. scores on similar scales, WASF is more distinctive and thus more accurate than WBF.

MaxRank Fuse performs aggregation by assigning each node the highest rank achieved in any primary ranking. Thus, a candidate with a high rank in a single primary ranking obtains a high rank in the aggregation.

Rank aggregation can result in ties if two or more nodes receive the same rank. NetworkPrioritizer can leave ties unresolved or break them arbitrarily.

Furthermore, the Ranking Manager provides two common measures of ranking distance, the Spearman footrule and the Kendall tau (Dwork et al., 2001). The Spearman footrule is the sum, over all nodes, of the difference between the ranks of a node in two compared rankings. The Kendall tau distance between two rankings is the number of nodes with different ranks.

Rank lists and rank list distances can be imported from, or exported to, plain text files for further analysis (see web site for file format details).

2.3 Batch functionality

To facilitate the prioritization of nodes in multiple networks, NetworkPrioritizer provides batch functionality. First, NetworkPrioritizer computes all centrality measures for each network and saves the resulting primary rankings to plain text files. Second, the primary rankings are re-imported and aggregated for each network separately.

3 CASE STUDY

A network of both protein–protein interactions and functional similarity links was compiled from BioMyn (Ramírez et al., 2012) and FunSimMat (Schlicker et al., 2010), respectively, for proteins encoded by genes in genomic loci associated with Crohn’s disease (Franke et al., 2010). Proteins associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or Crohn’s disease as a subtype of IBD, were used as seed nodes for the network analysis (see web site). The 10 top-ranked proteins function in the ‘immune system process’, ‘response to stress’, ‘signal transduction’ and ‘homeostatic process’ according to their Gene Ontology annotation. Since these processes are closely related to IBD (Zhu and Li, 2012), the proteins are promising candidates for further experimental studies.

4 CONCLUSIONS

NetworkPrioritizer is a versatile Cytoscape plugin that enables the ranking of individual network nodes based on their relevance for connecting a set of seed nodes to the rest of the network. The plugin computes centrality measures for unweighted and weighted networks and provides rank aggregation methods and ranking distance calculations. With its modular and extensible software design, NetworkPrioritizer is a very useful tool for integrative network-based prioritization of, e.g. candidate disease genes.

Funding: Part of this study was financially supported by the BMBF through the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN) and the Greifswald Approach to Individualized Medicine (GANI_MED). The research was also conducted in the context of the DFG-funded Cluster of Excellence for Multimodal Computing and Interaction (MMCI).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Assenov Y, et al. Computing topological parameters of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:282–284. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP. Centrality and network flow. Soc. Networks. 2005;27:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Doncheva NT, et al. Recent approaches to the prioritization of candidate disease genes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Med. 2012a;4:429–442. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncheva NT, et al. Topological analysis and interactive visualization of biological networks and protein structures. Nat. Protoc. 2012b;7:670–685. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwork C, et al. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW10) Hong Kong, China: 2001. Rank aggregation methods for the web; pp. 613–622. [Google Scholar]

- Franke A, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker B, et al. Exploration of biological network centralities with CentiBiN. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le DH, Kwon YK. GPEC: a Cytoscape plug-in for random walk-based gene prioritization and biomedical evidence collection. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2012;37:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, et al. Hubba: hub objects analyzer–a framework of interactome hubs identification for network biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W438–W443. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl T, et al. Node centrality in weighted networks: generalizing degree and shortest paths. Soc. Networks. 2010;32:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F, et al. Novel search method for the discovery of functional relationships. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:269–276. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari D. Explaining all three-alternative voting outcomes. J. Econ. Theory. 1999;87:313–355. [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker A, et al. Improving disease gene prioritization using the semantic similarity of gene ontology terms. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i561–i567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranchevent LC, et al. A guide to web tools to prioritize candidate genes. Brief. Bioinform. 2010;12:22–32. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, et al. iCTNet: a Cytoscape plugin to produce and analyze integrative complex traits networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:380. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Li YR. Oxidative stress and redox signaling mechanisms of inflammatory bowel disease: updated experimental and clinical evidence. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012;237:474–480. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]