Abstract

Epigenetics generates a considerable interest in the field of research on complex traits, including obesity and diabetes. Recently, we reported a number of epipolymorphisms in the placental leptin and adiponectin genes associated with maternal hyperglycemia during pregnancy. Our results suggest that DNA methylation could partly explain the link between early exposure to a detrimental fetal environment and an increased risk to develop obesity and diabetes later in life. This brief report discusses the potential importance of adipokine epigenetic changes in fetal metabolic programming. Additionally, preliminary data showing similarities between methylation variations of different tissues and cell types will be presented along with the challenges and future perspectives of this emerging field of research.

Keywords: leptin, adiponectin, fetal programming, Barker hypothesis, gestational diabetes, placenta, DNA methylation, gene expression

Obesity is a recognized risk factor for a number of metabolic disorders including pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).1 GDM is defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.2 Its prevalence ranges from 2% to 10% and can reach 20% in high-risk populations.3,4 GDM is the most common form of hyperglycemic disorder during pregnancy, and affected women are at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes (T2D) later in life.5 Furthermore, offspring exposed to maternal hyperglycemia during their in utero development have been shown to be more prone to metabolic disorders related to excess weight and insulin resistance, as early as adolescence and young adulthood.6,7

A few years ago, we undertook a research program aiming at understanding whether a suboptimal intrauterine environment alters the newborn’s methylome signature (the genome DNA methylation program). From an evolutionary standpoint, we can postulate that these epigenetic changes evolved at some point in history in order to match the efficiency of a newborn’s metabolism with the poor postnatal environment that he would have faced.8 In the 21st century however, metabolic programming to optimize energy storage and fuel efficiency are believed to increase the long-term susceptibility of the newborn to obesity and associated metabolic disorders. Indeed, access to food is not any longer a challenge in developed countries as well as in most developing countries.

The risk of developing obesity and its related metabolic disorders after exposure to a suboptimal intrauterine environment was first proposed by David J. Barker.9 It was supported by a large number of epidemiological studies highlighting the importance of intrauterine life for the metabolic health programming of the newborn.10,11 However, the underlying molecular mechanisms are still poorly understood. Recently, the hypothesis of epigenetic mechanisms emerged to explain the link between an exposure to an adverse fetal environment and obesity later in life.12 DNA methylation is the most studied epigenetic mark. It consists in the addition of a methyl group on the fifth carbon of the cytosines within cytosine-guanine dinucleotides (CpGs).13 This modification is sensitive to environmental stimuli but is also mitotically stable and heritable.14 Hence, it can be stable over time and passed on to the next generations.13 DNA methylation is generally associated with gene transcription repression, and so by consequence a low level of methylation (usually in the promoter region of the genes) allows a higher expression of the encoded protein.15

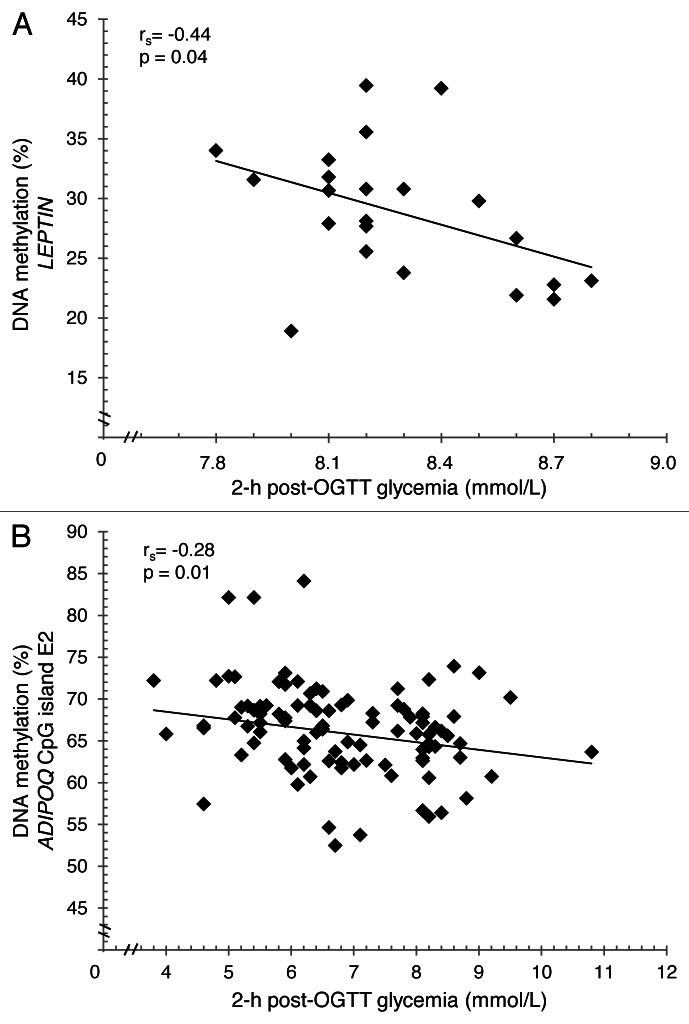

Keeping in mind this context, we first focused our investigations on the impact of maternal hyperglycemia on epigenetic changes at candidate gene loci involved in energy metabolism regulation. We therefore studied leptin and adiponectin genes DNA methylation levels in placenta biopsies and cord blood samples exposed or not to GDM (hyperglycemic in utero environment).16,17 We are aware that many other genes are implicated in obesity-related disorders and might be influenced by fetal epigenetic adaptations. However, these well-known adipokines were obvious candidate genes for metabolic disorders because they are secreted by the adipose tissue and involved in energy metabolism and insulin sensibility regulation.18 Briefly, we have reported that placental DNA methylation profiles of the two adipokines were influenced by exposure to maternal hyperglycemia.16,17 Interestingly, DNA methylation levels of leptin and adiponectin genes decreased with increased blood glucose concentration (2 h post-OGTT) in the fetal side placenta tissue suggesting that maternal hyperglycemia (insulin does not cross the placental barrier) has similar effects on both genes (Fig. 1). However, we observed in tissue from the maternal side of the placenta that leptin gene DNA methylation increased with post-prandial hyperglycemia (2 h post-OGTT), whereas the DNA methylation at the adiponectin gene locus decreased with increased insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). These observations is counterintuitive (DNA methylation is associated with gene expression repression as our results suggest), since insulin is known to upregulate leptin transcription and downregulate adiponectin gene expression.19,20 This apparent contradiction is not easy to explain, but we can hypothesize that DNA methylation changes at these two loci are induced to partially counterbalance the effects of insulin on these genes’ expression regulation. Studies in adipose tissue would clearly be helpful to better understand this phenomenon. Interestingly, associations were also observed between the epipolymorphisms tested in these studies and leptin gene expression or circulating concentration of both adiponectin and leptin.16,17 These observations suggest that DNA methylation changes at these loci are functional and potentially reflect biological phenomena occurring in other cell types such as adipocytes.

Figure 1. Correlation between leptin gene promoter (A) or adiponectin CpG island E2 (B) DNA methylation levels and 2 h post-OGTT glycemia. Data were corrected for anthropometric confounders (BMI and weight gain between first and third trimester).

Placenta is a key regulator of feto-maternal nutrient exchange and develops in parallel of the fetus. Therefore, we expect that our observations on the fetal side of the placenta reflect epigenetic marks in other key fetal tissues involved in energy and growth. It is likely that disturbances of adiponectin and leptin methylome in other tissues involved in energy metabolism regulation (e.g., adipose tissue) may interfere with postnatal growth and development. Although it has yet to be tested, we expect that the reported disturbances of the newborn DNA methylation profile in response to GDM exposure will be fairly stable throughout life. They would thus partly explain the “metabolic programming” hypothesized by Barker. This long-term effect has been suggested previously for the leptin gene in one other study.14 This study argued that the epigenome signature at birth could have long-term functional impacts on energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity, thus triggering the newborn’s long-term susceptibility to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Our results strengthen the hypothesis that epigenetic variations are part of the process linking hyperglycemic exposure to the long-term risk of metabolic disorders in offspring using adipokines genes as proof of concept. We suspect that DNA methylation levels at many other genes involved in fetal growth, development and energy metabolism, for instance, will also be modulated by an exposure to maternal hyperglycemia. One of the challenges that epigenetics will tackle is precisely to reveal which genes are part of known—or still unknown—pathways involved in GDM-related fetal programming.

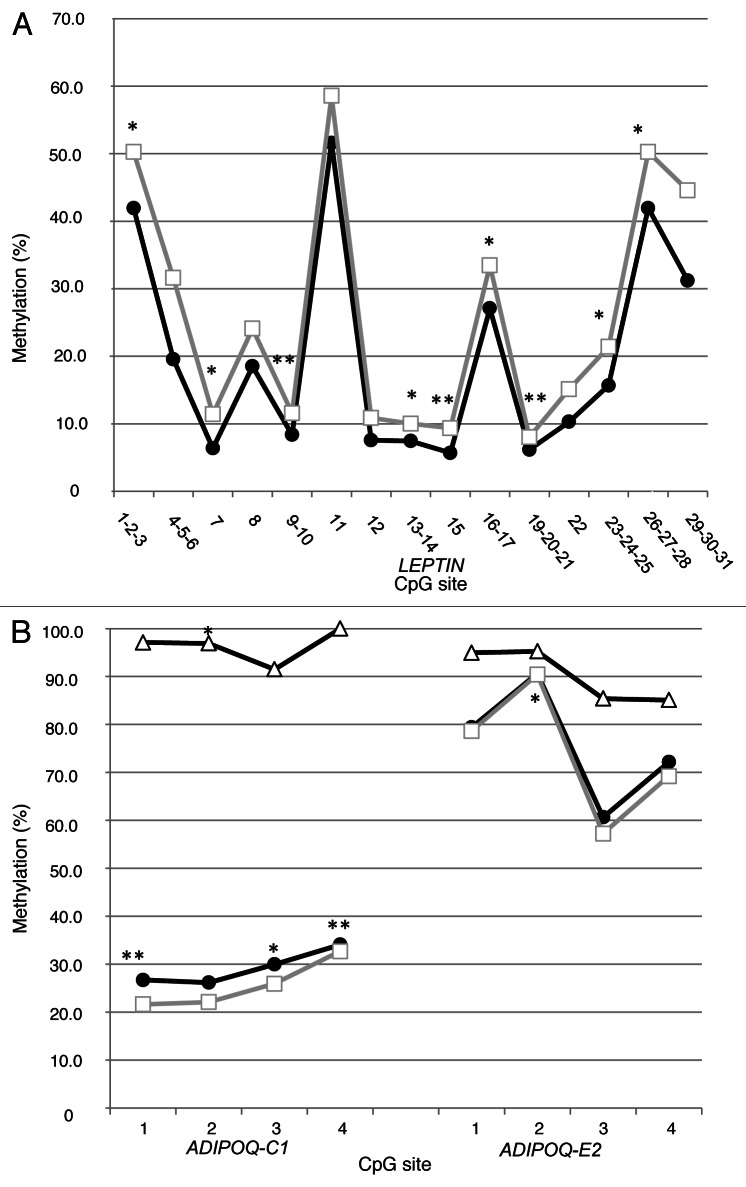

Another important challenge in human epigenetic studies is the access to appropriate, informative tissues. In the context of adipokines, the ideal tissues are obviously adipose tissues but this is hardly ethically acceptable for newborns and infants. Currently, we rely on placenta biopsies and cord blood samples to conduct our DNA methylation analyses. Cord blood cells are from fetal origin and somewhat readily accessible. In addition, circulating cord blood cells have been shown to be involved in inflammation regulation (and inflammation is a landmark of obesity).21 Placenta was also selected because of its central role in energy transfer from the mother to the fetus; it is metabolically very active and is associated with fetal growth and development (key phenomena since birth weight is strongly associated with an increased long-term obesity risk).22,23 We expect that both cell types will at least partially reflect the DNA methylation profile in other tissues (e.g., adipose tissue). How the DNA methylation profile correlates between cell types has been shown for specific loci but remains mostly unknown; limited data suggest that it may vary depending on tissues and exposure. Interestingly, additional analyses in our samples comparing DNA methylation values of CpG sites in leptin and adiponectin genes across cord blood samples and maternal and fetal placenta biopsies suggest that cytosine methylation variations share some similarities across these tissues. As illustrated, methylation levels seem to vary around a similar mean value at each CpG site of leptin (Fig. 2A) and adiponectin (Fig. 2B) genes. This was once observed before for leptin, in liver and visceral adipocyte fractions of white adipose tissue, by Marchi et al., but was not discussed by the authors.24 At the least, these observations suggest that DNA methylation varies concurrently between tissues around predefined (heritable?) values, which seem independent from one CpG site to another. We hypothesize that the variability in DNA methylation (around those “predefined” points) is induced by stochastic, genetic (gene polymorphisms), environmental as well as metabolic factors (as we have shown). Methylation values of specific CpG sites under normal conditions (“predefined” values) as well as the mechanisms involved in the establishment and regulation of DNA methylation under these conditions are still poorly defined. To increase our understanding of these values and mechanisms could help us assess the impact of genotype, environment and stochastic events on DNA methylation alterations and their role in pathogenesis.25,26 Further studies will also be needed to determine the potential heritability of the predefined DNA methylation values.

Figure 2. (A) Average methylation levels for CpG sites analyzed in maternal (□) and fetal (•) sides of the placenta for leptin gene promoter (n = 47). In (B), cord blood (Δ) (n = 39) and maternal (□) and fetal (•) placental tissues (n = 97) average cytosine methylation for adiponectin gene CpG island C1 and E2. Spearman correlation between methylation of CpG sites in maternal and fetal tissues and cord blood: *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01. CpG sites analyzed were the same as previously described.16,17

The DNA methylation correlation between tissues is incomplete (Tables 1 and 2). Even more intriguing, despite relatively similar variations around the “predefined” set-point values between fetal and maternal sides, the overall correlation for average methylation levels is fairly low for the leptin promoter region (rs = 0.20; p = 0.17) and is highly variable from one CpG site to another (Spearman correlations from r = 0.12 to 0.54) (Table 1). We observed a similar phenomenon in the ADIPOQ where despite obvious similar patterns in the population (Fig. 2B), the individual correlations at each site were fairly low (correlations between maternal and fetal placenta: ADIPOQ-C1 rs = 0.18; p = 0.07 and ADIPOQ-E2 rs = 0.14; p = 0.17). The correlation between each CpG sites was lower for the adiponectin gene across cord blood and both placental tissues (rs = 0.02–0.34) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Spearman correlation coefficient between CpG sites methylation of leptin gene promoter (n = 47) and adiponectin gene loci C1 and E2 (n = 97) in maternal and fetal sides of placenta.

| CpG sites | rs | p value |

|---|---|---|

|

LEPTIN |

|

|

|

1–2–3 |

0.31 |

0.04 |

|

4–5–6 |

0.12 |

0.43 |

|

7 |

0.30 |

0.04 |

|

8 |

0.22 |

0.13 |

|

9–10 |

0.40 |

< 0.01 |

|

11 |

0.01 |

0.96 |

|

12 |

0.19 |

0.19 |

|

13–14 |

0.32 |

0.03 |

|

15 |

0.54 |

< 0.01 |

|

16–17 |

0.37 |

0.01 |

|

19–20–21 |

0.44 |

< 0.01 |

|

22 |

0.23 |

0.12 |

|

23–24–25 |

0.34 |

0.02 |

|

26–27–28 |

0.31 |

0.04 |

|

29–30–31 |

0.25 |

0.09 |

|

1 to 31 (mean) |

0.20 |

0.17 |

|

ADIPOQ-C1 |

|

|

|

1 |

0.30 |

< 0.01 |

|

2 |

0.13 |

0.22 |

|

3 |

0.24 |

0.02 |

|

4 |

0.27 |

0.01 |

|

1 to 4 (mean) |

0.18 |

0.07 |

|

ADIPOQ-E2 |

|

|

|

1 |

0.02 |

0.84 |

|

2 |

0.25 |

0.02 |

|

3 |

0.06 |

0.56 |

|

4 |

0.10 |

0.34 |

| 1 to 4 (mean) | 0.14 | 0.17 |

Table 2. Spearman correlation coefficient between cord blood CpG sites methylation for adiponectin gene loci C1 and E2 and maternal and fetal sides of placenta (n = 39).

| |

Maternal side |

Fetal side |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG sites | rs | p value | rs | p value |

|

ADIPOQ-C1 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

-0.10 |

0.54 |

-0.14 |

0.38 |

|

2 |

-0.02 |

0.88 |

-0.34 |

0.04 |

|

3 |

0.25 |

0.12 |

-0.06 |

0.74 |

|

4 |

N/A* |

|

N/A* |

|

|

1 to 3 (mean) |

0.13 |

0.42 |

-0.15 |

0.36 |

|

ADIPOQ-E2 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

-0.06 |

0.71 |

0.03 |

0.88 |

|

2 |

-0.05 |

0.76 |

-0.08 |

0.63 |

|

3 |

0.08 |

0.64 |

0.02 |

0.93 |

|

4 |

-0.20 |

0.23 |

-0.14 |

0.40 |

| 1 to 4 (mean) | 0 | 0.10 | -0.08 | 0.64 |

Values are not available since cord blood was fully methylated (100%) at this CpG site.

The relatively limited number of samples and tissues analyzed in current epigenetic studies is also a challenging issue. We believe that epigenetic studies should target to apply standards similar to those of traditional genetic research, using larger samples and including more than one population (or cohort) to confirm the results. To achieve this goal, new affordable epigenotyping strategies will have to be developed as the cost for epigenetic analyses is currently about 20 times more expensive than “standard” genetic analyses for the detection of polymorphisms. Cost is an important issue because it directly limits the number of samples (between 50 and 300 in the largest studies) and tissues (limited to a single tissue in most studies) in available reports. Although the DNA methylation microarray such as the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChips offers a cost-effective but still expensive approach, new technologies such as whole epigenome-sequencing are needed to enable testing of DNA methylation levels across the whole genome and in larger samples (hopefully in many tissues). Such technology will also probably lead to many statistical analyses challenges (such as the burden of multiple testing) similar to those that were tackled when the use of genome-wide association study (GWAS) exploded a few years ago.

Another efficient and cost-effective way to increase our confidence in the results of epigenetic analyses is to expend the analysis strategy to other “omic” sciences. This is precisely the approach that we have favored and currently apply. Accordingly, we measure mRNA and protein levels of the targeted genes when expressed and secreted by the available tissue. Taken together epigenetic, transcriptomic and proteomic results, when converging, are strong arguments in support of the results; they increase our confidence that the observed associations reflect true biologic phenomena. When feasible, this strategy should be applied.

The accumulated evidence now strongly supports an association of detrimental in utero environment with newborns’ epigenetic changes. However, the impacts of these changes on the long-term health of newborns remain to be uncovered. This knowledge is fundamental to prove that epigenetics is involved in fetal metabolic programming (Barker’s hypothesis). Large longitudinal (from birth to adulthood) cohorts with repeated measurement of phenotypes, genotypes and epigenotypes (hopefully in various key tissues such as adipose tissue) is needed to achieve this goal. Such a prospect may appear ambitious, but large longitudinal cohort studies would indeed provide the solid scientific ground to support the role of epigenetics in fetal metabolic programming in addition to arguments to shore up obesity prevention programs to be applied as early as conception. To provide women with an early pregnancy lifestyle intervention would allow to test whether epigenetic changes related to maternal metabolic disorders can be prevented. Finally, such studies would also add to the scientific evidence supporting the importance of epigenetic changes among the early determinants of adult chronic diseases.

At the present time, only a few studies have been performed at the molecular level to support the involvement of epigenetics in newborn metabolic programming. We have shown that maternal glycemia is associated with DNA methylation changes at two adipokine gene loci in the placenta; yet many more obesity-related genes remain to be investigated. According to our results, these adipokine epigenetic adaptations are likely functional and may have impacts on the long-term regulation of newborns’ energy metabolism. Furthermore, our latest findings suggest that DNA methylation of each cytosine within the leptin and adiponectin genes varies concurrently around “predefined” values, a biologic phenomenon virtually unexplored. These results pave the way for the use of tissues that would be more readily available to predict DNA methylation of adipokines in the newborn. Studies will have to be conducted with adipocytes to confirm our observations because adipocytes are at the center-point of the energy metabolism regulation that secretes these same adipokines. Yet a number of challenges remain and will have to be addressed in the next years to see epigenetics meet its promises.

Acknowledgments

We also express our gratitude to Céline Bélanger, Chicoutimi Hospital, for her thoughtful language revision of the manuscript. L.B. and M.-F.H. are junior research scholars from the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec. M.-F.H. is also supported by a Canadian Diabetes Association clinical scientist award. L.B. and M.-F.H. are members of the FRSQ-funded Centre de recherche clinique Étienne-Le Bel (affiliated with Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Sherbrooke).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Authors’ Contributions

A.-A.H. performed the data analysis/interpretation and wrote the manuscript; M.-F.H. and L.B. conceived the study design and revised the manuscript.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/adipocyte/article/22055

References

- 1.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J, England LJ, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2070–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2559a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi SH, Zhao ZS, Lee YJ, Kim SK, Kim DJ, Ahn CW, et al. The different mechanisms of insulin sensitizers to prevent type 2 diabetes in OLETF rats. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:411–8. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Dietz PM, England L, Morrow B, Callaghan WM. Trends in pre-pregnancy obesity in nine states, 1993-2003. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:986–93. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galtier F. Definition, epidemiology, risk factors. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:628–51. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Schmidt MM, Mullen JA, Charles MA, Pettitt DJ. Childhood obesity and metabolic imprinting: the ongoing effects of maternal hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2287–92. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Lamichhane AP, D’Agostino RB, Jr., Liese AD, Vehik KS, et al. Association of intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes and obesity with type 2 diabetes in youth: the SEARCH Case-Control Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1422–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker DJ. Intrauterine programming of adult disease. Mol Med Today. 1995;1:418–23. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(95)90793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hales CN, Barker DJ. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull. 2001;60:5–20. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tounian P. Programming towards childhood obesity. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;58(Suppl 2):30–41. doi: 10.1159/000328038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC. Epigenetic changes in early life and future risk of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:72–83. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobi EW, Lumey LH, Talens RP, Kremer D, Putter H, Stein AD, et al. DNA methylation differences after exposure to prenatal famine are common and timing- and sex-specific. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4046–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner BM. Defining an epigenetic code. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:2–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb0107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouchard L, Thibault S, Guay SP, Santure M, Monpetit A, St-Pierre J, et al. Leptin gene epigenetic adaptation to impaired glucose metabolism during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2436–41. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouchard L, Hivert MF, Guay SP, St-Pierre J, Perron P, Brisson D. Placental adiponectin gene DNA methylation levels are associated with mothers’ blood glucose concentration. Diabetes. 2012;61:1272–80. doi: 10.2337/db11-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havel PJ. Control of energy homeostasis and insulin action by adipocyte hormones: leptin, acylation stimulating protein, and adiponectin. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:51–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDougald OA, Hwang CS, Fan H, Lane MD. Regulated expression of the obese gene product (leptin) in white adipose tissue and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9034–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fasshauer M, Klein J, Neumann S, Eszlinger M, Paschke R. Hormonal regulation of adiponectin gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:1084–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Signalling role of adipose tissue: adipokines and inflammation in obesity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1078–81. doi: 10.1042/BST20051078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curhan GC, Chertow GM, Willett WC, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Manson JE, et al. Birth weight and adult hypertension and obesity in women. Circulation. 1996;94:1310–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.6.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Ascherio AL, Stampfer MJ. Birth weight and adult hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in US men. Circulation. 1996;94:3246–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.12.3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchi M, Lisi S, Curcio M, Barbuti S, Piaggi P, Ceccarini G, et al. Human leptin tissue distribution, but not weight loss-dependent change in expression, is associated with methylation of its promoter. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1198–206. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.10.16600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langevin SM, Houseman EA, Christensen BC, Wiencke JK, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, et al. The influence of aging, environmental exposures and local sequence features on the variation of DNA methylation in blood. Epigenetics. 2011;6:908–19. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]