Summary

Background

In resource-limited settings where no safe alternative to breastfeeding exists, WHO recommends that antiretroviral prophylaxis be given to either HIV-infected mothers or infants throughout breastfeeding. We assessed the effect of 28 weeks of maternal or infant antiretroviral prophylaxis on postnatal HIV infection at 48 weeks.

Methods

The Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition (BAN) Study was undertaken in Lilongwe, Malawi, between April 21, 2004, and Jan 28, 2010. 2369 HIV-infected breastfeeding mothers with a CD4 count of 250 cells per μL or more and their newborn babies were randomly assigned with a variable-block design to one of three, 28-week regimens: maternal triple antiretroviral (n=849); daily infant nevirapine (n=852); or control (n=668). Patients and local clinical staff were not masked to treatment allocation, but other study investigators were. All mothers and infants received one dose of nevirapine (mother 200 mg; infant 2 mg/kg) and 7 days of zidovudine (mother 300 mg; infants 2 mg/kg) and lamivudine (mothers 150 mg; infants 4 mg/kg) twice a day. Mothers were advised to wean between 24 weeks and 28 weeks after birth. The primary endpoint was HIV infection by 48 weeks in infants who were not infected at 2 weeks and in all infants randomly assigned with censoring at loss to follow-up. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00164736.

Findings

676 mother–infant pairs completed follow-up to 48 weeks or reached an endpoint in the maternal-antiretroviral group, 680 in the infant-nevirapine group, and 542 in the control group. By 32 weeks post partum, 96% of women in the intervention groups and 88% of those in the control group reported no breastfeeding since their 28-week visit. 30 infants in the maternal-antiretroviral group, 25 in the infant-nevirapine group, and 38 in the control group became HIV infected between 2 weeks and 48 weeks of life; 28 (30%) infections occurred after 28 weeks (nine in maternal-antiretroviral, 13 in infant-nevirapine, and six in control groups). The cumulative risk of HIV-1 transmission by 48 weeks was significantly higher in the control group (7%, 95% CI 5–9) than in the maternal-antiretroviral (4%, 3–6; p=0·0273) or the infant-nevirapine (4%, 2–5; p=0·0027) groups. The rate of serious adverse events in infants was significantly higher during 29–48 weeks than during the intervention phase (1·1 [95% CI 1·0–1·2] vs 0·7 [0·7–0·8] per 100 person-weeks; p<0·0001), with increased risk of diarrhoea, malaria, growth faltering, tuberculosis, and death. Nine women died between 2 weeks and 48 weeks post partum (one in maternal-antiretroviral group, two in infant-nevirapine group, six in control group).

Interpretation

In resource-limited settings where no suitable alternative to breastfeeding is available, antiretroviral prophylaxis given to mothers or infants might decrease HIV transmission. Weaning at 6 months might increase infant morbidity

Funding

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Introduction

Although global mother-to-child transmission of HIV has been substantially reduced, postnatal HIV transmission remains a challenge in resource-limited settings. In such settings, often no safe and feasible alternative to breastfeeding is available. 2010 WHO guidelines1 recommend that HIV-infected mothers whose infants are uninfected or of unknown HIV status exclusively breastfeed their children for the first 6 months of life, and introduce appropriate complementary foods thereafter while continuing to breastfeed for the next 6 months.

Studies have shown that antiretroviral drugs given to the mother2–7 or infant2,8–11 for up to 6 months after delivery reduce HIV transmission to the breastfeeding infant. On the basis of this emerging evidence, WHO now recommends antiretroviral prophylaxis for the mother or infant throughout breastfeeding.1,12 If national authorities promote breastfeeding with antiretroviral drugs as the most appropriate feeding practice for mothers who are ineligible for lifelong antiretroviral therapy, countries must decide whether to provide antiretroviral prophylaxis to mothers or to infants after careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of both options.

The Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition (BAN) study2 is the only completed randomised trial to include mothers and infants given antiretroviral drugs for prevention of postnatal HIV-1 transmission. Mother–infant pairs were randomly assigned to one of three 28-week antiretroviral groups (maternal triple antiretrovirals, infant nevirapine, or no extended postnatal antiretrovirals) and two nutritional intervention groups. By 28 weeks post partum, infants in both the maternal-antiretroviral group and the infant-nevirapine group had significantly lower risk of postnatal HIV trans mission than did the control group.2 In this report, we describe results from the follow-up of these cohorts after 28 weeks and review the safety and effects of weaning and stopping of antiretroviral prophylaxis at 28 weeks postnatally. Specifically, we assess the effect of 28 weeks of maternal or infant antiretroviral prophylaxis on postnatal HIV infection or death by 48 weeks and describe breastfeeding cessation, serious adverse events, and maternal and infant deaths.

Methods

Patients

In the BAN randomised controlled trial, investigators recruited women testing HIV positive through a prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme at antenatal clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi, who came to Bwaila Hospital between April 21, 2004, and Jan 28, 2010. Women had to provide written informed consent and meet prenatal and postnatal eligibility criteria that are described elsewhere.2,13 Briefly, women had to have been pregnant for 30 weeks or less, be aged 14 years or older, have a CD4 count of 250 cells per μL or more (≥200 cells per μL before July 24, 2006; change in accordance with Malawi Ministry of Health guidelines for HIV treatment), and have used no antiretroviral drugs previously (including the HIVNET 012 regimen14). Postnatally, mothers and infants could have no disorder precluding study interventions. Additionally, infant birthweight had to be more than 2000 g.

The BAN study protocol was approved by the Malawi National Health Science Research Committee and by institutional review boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Randomisation and masking

In the immediate post-partum period, mother–infant pairs were randomly assigned to one of six groups in a factorial design: a two-group maternal nutritional intervention (nutritional supplement and no supplement) by a three-group antiretroviral intervention (maternal-antiretroviral, infant-nevirapine, and control groups). We used a variable-block design for randomisation, with the order decided by a pseudorandom number generator and a fixed, preselected seed. Patients and local clinical staff were not masked to treatment allocation, but all other study investigators, including the data management and analysis staff, were masked.

Procedures

Irrespective of antiretroviral intervention group, all mothers in labour and their newborn babies were offered one dose of oral nevirapine (mother 200 mg; infant 2 mg/kg) and zidovudine and lamivudine to be taken twice a day for 7 days (mothers 300 mg zidovudine and 150 mg lamivudine in one tablet [Combivir, GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA, USA]; infants 2 mg/kg zidovudine and 4 mg/kg lamivudine syrups).15

Women assigned to the maternal nutritional intervention group were given a lipid-based nutrition supplement throughout breastfeeding. Because investigators reported no statistical interactions between the nutritional and antiretroviral interventions for any primary outcomes,2 we focus on antiretroviral interventions in this report. Primary results of the nutritional intervention have been reported previously.16

Women in the maternal-antiretroviral group received lamivudine and zidovudine twice a day for 28 weeks, and nevirapine (200 mg) once daily for the first 14 days postpartum and twice a day from 15 days to 28 weeks. In January, 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about the risks of hepatotoxicity with nevirapine, specifically when women with a CD4 count greater than 250 cells per μL start treatment.17 On the basis of this public health advisory, the postnatal nevirapine component of the maternal regimen was replaced with nelfinavir (1250 mg) twice a day in February, 2005. After February, 2006, nelfinavir was replaced with 400 mg lopinavir and 100 mg ritonavir (Kaletra, Abbott, MA, USA) twice a day for reasons of availability, safety, and potency.

Babies in the infant-nevirapine group received a dose of nevirapine that increased with age: 10 mg daily in the first 2 weeks, 20 mg daily between weeks 3 and 18, and 30 mg daily from week 19 to week 28. All antiretroviral interventions were stopped after mothers reported cessation of breastfeeding or after 28 weeks, whichever came first. Pairs in the control group received no treatment post partum after the first 7 days. In March, 2008, a data safety monitoring board at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases reviewed the data from the first 1857 mother–infant pairs randomly assigned and noted that the HIV transmission rate was significantly higher in infants in the control group than in those in one of the antiretroviral groups. The board recommended that researchers stop enrolment to the control group and continue random isation to both antiretroviral groups. Enrolment to the control group was halted on March 26, 2008, after 668 of the planned 806 mother–infant pairs had been assigned. All pairs already in the control group and less than 21 weeks since birth were consulted about the study results and offered the choice to receive maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis, infant nevirapine prophylaxis, or to remain in the control group.18

With a standardised protocol derived from the WHO breastfeeding counselling training manual,19 all mothers were individually advised to breastfeed exclusively for the first 24 weeks post partum and then wean between 24 and 28 weeks. At each visit, women reported the type of infant feeding since their last visit: exclusive breastfeeding, mixed feeding with breastmilk and other liquids or solids, or no breastfeeding. To minimise infant mal nutrition after cessation of breastfeeding, mothers were provided with a breastmilk-replacement food for the infants—a locally produced ready-to-use therapeutic food commonly used in Malawi for treatment of severe acute malnutrition in children.20 No infant formula was provided.

All women received a family maize supplement (2 kg per week), recommended vaccines, and treatment for intercurrent illnesses. To be consistent with Malawi Ministry of Health and Population guidelines (July, 2005) and 2006 WHO guidance, from June, 2006, prophylactic co-trimoxazole was given to HIV-infected mothers with CD4 counts of less than 500 cells per μL (480 mg twice daily) and to all HIV-exposed infants older than 6 weeks (240 mg daily) until 36 weeks of age, or indefinitely for HIV-infected infants.21

Mother–infant pairs were followed up at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, 21, 24, 28, 32, 36, 42, and 48 weeks post partum, with the last pair completing follow-up in January, 2010. Infants were tested for HIV infection at birth, 2, 12, 28, and 48 weeks with Roche Amplicor 1.5 DNA PCR (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Positive results were confirmed by tests of another specimen, and the window of seroconversion was narrowed with tests of dried blood-spot specimens from interim visits.2 Infants infected by the age of 2 weeks and their mothers were disenrolled from the study and referred for care. Mother–infant pairs lost to follow-up before 48 weeks were traced by a team of community nurses to establish vital and HIV status.

Breastfeeding practices and timing of breastfeeding cessation were noted by trained staff with standardised questionnaires at weeks 4, 8, 12, 18, 21, 24, 28, 32, 36, 42, and 48. Internal validity checks across visits and forms were used to estimate a date of weaning for every mother–infant pair.

Clinical and laboratory adverse events identified at regular study visits and interim sick visits were documented and graded according to toxicity tables from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of AIDS (2006 version).22 Mothers who developed AIDS-defining diseases or whose CD4 counts fell to less than 250 cells per μL were immediately referred for treatment. Infant growth faltering (serious adverse event) and failure to thrive (cause of death) were defined by oedema (due to malnutrition) or severe wasting (weight <70% expected value for length of body).23,24

During the study, cause of death was ascertained by study clinicians, with subsequent review by the local and CDC medical monitors (MCH and APK, respectively). After study completion, two physicians independently reviewed each infant (CvdH, APK) and maternal (DJJ, CvdH) death and reached a consensus about cause of death.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint for efficacy of the maternal and infant antiretroviral interventions was detection of infant HIV infection by 48 weeks, in those uninfected at 2 weeks and in all infants randomly assigned. The secondary efficacy endpoint was infant HIV infection or death by 48 weeks, in those alive and uninfected at 2 weeks and in all infants randomly assigned. Mother–infant pairs that switched from control to an intervention were censored at that time. For both the primary and secondary endpoints, infants lost to follow-up were censored at their last negative HIV test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the probability for the composite outcome of HIV infection or death by infant age. An extension of the Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess the probability of each outcome separately while allowing for competing risks of infant HIV infection and death, and therefore, avoiding the assumption that these outcomes are independent.25 Differences between the intervention groups and the control group were tested with log-rank tests (for the composite outcome) and Gray's test (for the competing risks analyses).26 The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios and CIs for HIV transmission comparing the two intervention groups with the control group, with stratification by random allocation to the nutritional supplement and adjustment for potential prognostic factors.

The BAN Study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00164736.

Role of the funding source

CDC representatives were part of the study team and were involved in the study design, coordination, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The study group had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the analysis, interpretation, and decision to submit for publication. The manufacturers of the study drugs had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data inter pretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Patients

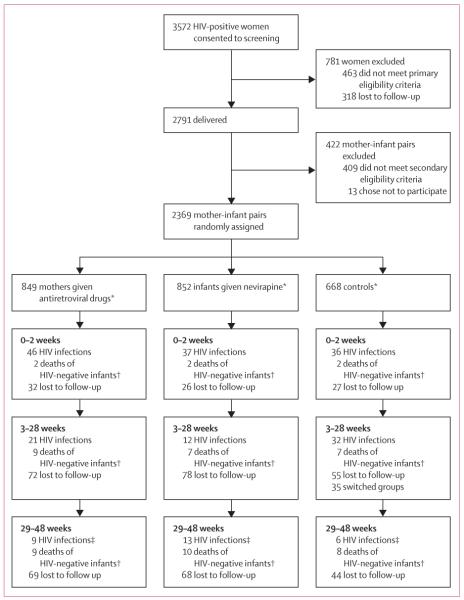

Of 3572 HIV-infected, pregnant women who consented to study screening, 3109 (87%) met the primary eligibility criteria, and 2791 went on to deliver liveborn infants (figure 1); 2382 (85%) mother-infant pairs met the secondary eligibility criteria. 1829 mother-infant pairs completed follow-up to 28 weeks.

Figure 1. Trial profile.

*Groups of uneven size because data safety and monitoring board recommended change in study design on March 26, 2008. †Infants HIV negative at last HIV test before death. ‡Two infants had an unknown HIV status because we were unable to confirm one positive test: one between weeks 42 and 48, and one at week 48; these two infants are not included in the HIV infection counts.

Baseline characteristics were well balanced across the control and antiretroviral intervention groups in all mother–infant pairs randomly assigned and in those remaining in study follow-up at the end of the 28-week intervention phase (table 1). On the basis of adherence reports from five follow-up visits, mothers reported taking all their antiretroviral doses a mean of 89% (SD 20) of the time and giving all infant antiretroviral doses 94% (14) of the time. By 48 weeks, 173 (20%) mother–infant pairs in the maternal-antiretroviral group, 172 (20%) in the infant-nevirapine group, and 126 (19%) in the control group were lost to follow-up (figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Randomly assigned |

Active follow-up at 28-week visit* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal antiretroviral (n=849) | Infant nevirapine (n=852) | Control (n=668) | Maternal antiretroviral (n=667) | Infant nevirapine (n=690) | Control (n=472) | p value† | |

| Mothers | |||||||

| Age (years) | 26 (22–29) | 25 (22–30) | 26 (22–29) | 26 (23–30) | 26 (23–30) | 26 (23–29) | 0·8298 |

| Education (>8 years of school) (%) | 301 (36%) | 309 (36%) | 210 (31%) | 242 (36%) | 245 (36%) | 147 (31%) | 0·1647 |

| Married (%) | 785 (92%) | 793 (93%) | 619 (93%) | 615 (92%) | 641 (93%) | 439 (93%) | 0·8443 |

| Body-mass index <17 kg/m2 (%) | 5 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0·3009 |

| CD4 (cells per μL) | 429 (324–565) | 440 (330–591) | 442 (334–586) | 436 (331–571) | 439 (331–591) | 451 (343–584) | 0·3302 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 109 (100–117) | 108 (100–117) | 108 (100–116) | 110 (102–117) | 108 (100–117) | 109 (101–117) | 0·0771 |

| Infants | |||||||

| Sex (% boys) | 422 (50%) | 426 (50%) | 341 (51%) | 346 (52%) | 347 (50%) | 236 (50%) | 0·7823 |

| Birthweight (kg) | 3·0 (2·7–3·2) | 3·0 (2·7–3·3) | 3·0 (2·7–3·3) | 3·0 (2·8–3·3) | 3·0 (2·7–3·3) | 3·0 (2·7–3·3) | 0·8923 |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%).

Excludes all mother–infant pairs in which the mother or infant died, the infant tested HIV positive, or the pair was lost to follow-up by the 28-week visit. Mother–infant pairs randomly assigned to the control group that switched to the maternal-antiretroviral or infant-nevirapine groups are also excluded.

p values based on Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for binary variables.

The self-reported frequency of exclusive breastfeeding at 24 weeks post partum was high in all groups (table 2). By 28 weeks, these proportions had decreased substantially to less than 10% (table 2). At 32 weeks, significantly more women in the maternal-antiretroviral and infant-nevirapine groups than in the control group reported no breastfeeding since their 28-week visit (p<0·0001; table 2). But by 48 weeks, the proportion reporting no breastfeeding since 42 weeks did not differ significantly between groups (table 2).

Table 2.

Mothers reporting exclusive, mixed, or no breastfeeding during study intervals by group

| Maternal antiretroviral |

Infant nevirapine |

Control |

p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastfeeding | Mixed breastfeeding | No breastfeeding | Exclusive breast feeding† | Mixed breastfeeding | No breastfeeding | Exclusive breastfeeding | Mixed breastfeeding | No breastfeeding | ||

| 13–18 weeks | 615/630 (98%) | 12/630 (2%) | 3/630 (<1%) | 665/676 (98%) | 8/676 (1%) | 3/676 (<1%) | 471/480 (98%) | 6/480 (1%) | 3/480 (<1%) | 0·9177 |

| 19–21 weeks | 594/618 (96%) | 13/618 (2%) | 11/618 (2%) | 644/662 (97%) | 14/662 (2%) | 4/662 (<1%) | 434/453 (96%) | 15/453 (3%) | 4/453 (<1%) | 0·1420 |

| 22–24 weeks | 543/612 (89%) | 38/612 (6%) | 31/612 (5%) | 581/643 (90%) | 33/643 (5%) | 29/643 (5%) | 387/440 (88%) | 33/440 (8%) | 20/440 (5%) | 0·8765 |

| 25–28 weeks | 44/599 (7%) | 149/599 (25%) | 406/599 (68%) | 57/638 (9%) | 151/638 (24%) | 430/638 (67%) | 24/439 (5%) | 120/439 (27%) | 295/439 (67%) | 0·9796 |

| 29–32 weeks | 1/564 (<1%) | 22/564 (4%) | 541/564 (96%) | 1/591 (<1%) | 22/591 (4%) | 568/591 (96%) | 3/406 (<1%) | 45/406 (11%) | 358/406 (88%) | <0·0001 |

| 33–36 weeks | 1/76 (1%) | 2/76 (3%) | 73/76 (96%) | 0/85 | 3/85 (4%) | 82/85 (96%) | 0/78 | 5/78 (6%) | 73/78 (94%) | 0·7374 |

| 37–42 weeks | 0/547 (<1%) | 21/547 (4%) | 526/547 (96%) | 1/574 (<1%) | 13/574 (2%) | 560/574 (98%) | 2/405 (<1%) | 18/405 (4%) | 385/405 (95%) | 0·1023 |

| 43–48 weeks | 1/552 (<1%) | 17/552 (3%) | 534/552 (97%) | 2/574 (<1%) | 12/574 (2%) | 560/574 (98%) | 1/389 (<1%) | 16/389 (4%) | 372/389 (96%) | 0·2448 |

Data are n/N (%). At each study visit, women were asked how they had fed their child since the previous visit; thus, the data from 13–18 weeks were reported at the 18-week visit and show infant feeding method since the 12-week visit.

Between 2 weeks and 48 weeks of life, 93 infants became infected with HIV (figure 1). Of these infants, 28 (30%) became infected after completion of the intervention phase at 28 weeks: six in the control group (Kaplan-Meier estimate 1%) versus 13 in the infant-nevirapine group (2%; p=0·4128) and nine in the maternal-antiretroviral group (1%; p=0·8886). 14 of these late transmissions occurred more than 42 days after the reported date of breastfeeding cessation (five in the maternal-antiretroviral group, six in the infant-nevirapine group, and three in the control group).

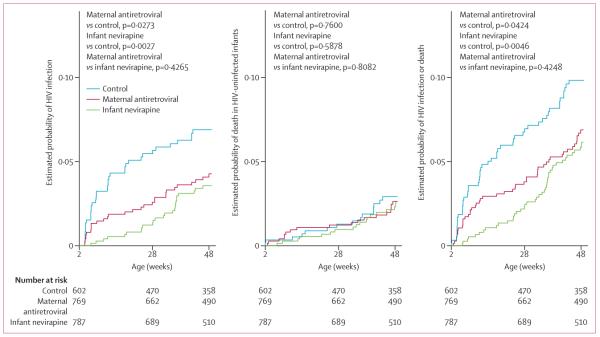

The cumulative risk of HIV-1 transmission by 48 weeks was significantly higher in the control group (7%, 95% CI 5–9) than in the maternal-antiretroviral (4%, 3–6) or the infant-nevirapine (4%, 2–5) groups (figure 2). The reduction in risk of HIV transmission from 2 weeks to 48 weeks was 48% (95% CI 23–74) in the infant-nevirapine group and 38% (9–67) in the maternal-antiretroviral group. Of all infants randomly assigned, irrespective of infection status at 2 weeks, the risk of HIV infection by 48 weeks was 12% (9–15) in the control group compared with 10% (7–12) in the maternal-antiretroviral (p=0·1436) and 8% (6–10) in the infant-nevirapine groups (p=0·0063; data not shown).

Figure 2. Cumulative risk of HIV infection (A), HIV-negative death (B), or HIV infection or death (C) in infants alive and HIV negative at 2 weeks.

*Estimated with the extension of the Kaplan-Meier estimator to allow for competing risks, when the two competing events were HIV infection and death of HIV-negative infants. Infants who did not test HIV positive or die were right censored at their last negative HIV test (ie, at the last time they were known to be HIV negative and alive). p values are based on Gray's test of equality of cumulative incidence functions26 (A, B) or the log-rank test (C).

After multivariate adjustment for maternal factors associated with infant HIV infection, maternal and infant antiretroviral regimens remained significantly associated with reduced risk for HIV transmission to infants aged 2–48 weeks (table 3). Reporting of continued breastfeeding was an independent predictor of HIV transmission by 48 weeks (table 3). We noted a significant interaction between reported breastfeeding and antiretroviral interventions; the effect of interventions on postnatal transmission was significant only when mothers reported breastfeeding (table 3).

Table 3.

Proportional hazards modelling of possible risk factors for infant HIV infection by 48 weeks

| Unadjusted* |

Adjusted† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Infant nevirapine vs control | 0·47 (0·28–0·77) | 0·0030‡ | 0·25 (0·13–0·49)§ | <0·0001 |

| Maternal antiretroviral vs control | 0·58 (0·36–0·94) | 0·0271 | 0·46 (0·27–0·81)§ | 0·0072 |

| Maternal baseline CD4 count (<350 vs ≥350 cells per μL) | 2·40 (1·60–3·61) | <0·0001 | 2·54 (1·68–3·83) | <0·0001 |

| Maternal age (per increase of 1 year) | 0·96(0·92–1·00) | 0·0628 | 0·95 (0·91–0·99) | 0·0198 |

| Reported breastfeeding vs no breastfeeding¶ | 4·55 (2·02–10·3) | 0·0003 | 9·06 (3·83–21·4) | <0·0001 |

Proportional hazards model with each risk factor as the only covariate, and stratified by nutritional group. Infant nevirapine, maternal antiretroviral, maternal baseline CD4, and maternal age included as time-independent covariates.

Proportional hazards model adjusted for all variables listed, stratified by nutritional group.

Proportional hazards assumption violated; p<0·0001.

Hazard ratio estimates for infant-nevirapine and maternal-antiretroviral groups are based on interaction terms with reported breastfeeding (ie, the effect of antiretroviral treatment while breastfeeding); the hazard of infection did not differ significantly between antiretroviral and control groups when the mother reported that she did not breastfeed.

Reported breastfeeding included as a time varying covariate. Breastfeeding based on mothers' reports at study visits describing infant feeding since previous visit. Reported breastfeeding as a time-dependent covariate is sometimes missing at the time of events (HIV infections), so corresponding events (HIV infections) are not counted in the proportional hazards model analysis. To avoid loss of information about events, we assumed that the infant was not weaned at the time of an event when it occurred within 1 month of the mother reporting she was still breastfeeding and no additional information was available.

The estimated risk of death of HIV-negative infants was roughly 3% in all groups (figure 2). The estimated risk of HIV infection or death by 48 weeks was significantly higher in the control group than in both antiretroviral groups (figure 2). Of all infants randomly assigned, the cumulative incidence of HIV infection or death by 48 weeks was 15% (12–18) in the control group versus 12% (10–15) in the maternal-antiretroviral group (p=0·1327) and 11% (8–13) in the infant-nevirapine group (p=0·0058; data not shown).

The rate of serious adverse events in infants from 29 weeks to 48 weeks (1·1 per 100 person-weeks, 95% CI 1·0–1·2) was significantly higher than in the intervention phase (0·7 per 100 person-weeks, 0·7–0·8; p<0·0001). Diarrhoea, malaria, growth faltering, tuberculosis, and deaths all occurred significantly more frequently after 28 weeks (table 4). All were unrelated to group and remained significant when HIV-infected infants were censored when they tested HIV positive (data not shown). Of the 75 infant deaths that occurred by 48 weeks, 38 occurred after 28 weeks: 13 in the infant-nevirapine group, 11 in the maternal-antiretroviral group, and 14 in the control group. Although the main causes of death during the intervention phase were pneumonia (n=12), sepsis (n=9), meningitis (n=3), and diarrhoea (n=2), the main causes of death after 28 weeks (n=38) were diarrhoea with (n=20) and without (n=2) failure to thrive, malaria (n=4), pneumonia (n=3), tuberculosis (n=2), and unknown (n=4). The occurrence and cause of death was unrelated to antiretroviral group (data not shown).

Table 4.

Rates of clinical serious adverse events by group and study period

| Group |

Study period |

Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal antiretroviral |

Infant antiretroviral |

No antiretroviral |

0–28 weeks |

29–48 weeks |

|

||||||||

| Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | p value | Number | Rate per 100 person-weeks | |

| Maternal | |||||||||||||

| Pneumonia | 6 | 0·019 | 4 | 0·012 | 6 | 0·026 | 13 | 0·023 | 3 | 0·010 | 0·1540 | 16 | 0·018 |

| Serious febrile illness | 16 | 0·051 | 16 | 0·049 | 7 | 0·030 | 15 | 0·027 | 24 | 0·077 | 0·0008 | 39 | 0·045 |

| Tuberculosis | 4 | 0·013 | 4 | 0·012 | 4 | 0·017 | 8 | 0·014 | 4 | 0·013 | 0·8562 | 12 | 0·014 |

| Diarrhoea | 4 | 0·013 | 2 | 0·006 | 2 | 0·009 | 4 | 0·007 | 4 | 0·013 | 0·4037 | 8 | 0·009 |

| Hepatitis, clinical | 2 | 0·006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0·004 | 0 | 0 | 0·2905 | 2 | 0·002 |

| Rash | 1 | 0·003 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0·004 | 2 | 0·004 | 0 | 0 | 0·2905 | 2 | 0·002 |

| Malaria | 4 | 0·013 | 4 | 0·012 | 1 | 0·004 | 6 | 0·011 | 3 | 0·010 | 0·8753 | 9 | 0·010 |

| Meningitis | 2 | 0·006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0·006 | 0·0585 | 2 | 0·002 |

| Nevirapine hypersensitivity* | 6 | 0·019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0·011 | 0 | 0 | 0·0671 | 6 | 0·007 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0·006 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0·004 | 0 | 0 | 0·2905 | 2 | 0·002 |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0·006 | 1 | 0·004 | 2 | 0·004 | 1 | 0·003 | 0·9278 | 3 | 0·003 |

| Syphilis | 1 | 0·003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0·002 | 0 | 0 | 0·4548 | 1 | 0·001 |

| Death† | 1 | 0·003 | 2 | 0·006 | 6 | 0·026 | 2 | 0·004 | 7 | 0·022 | 0·0087 | 9 | 0·010 |

| Infant | |||||||||||||

| Serious febrile illness | 78 | 0·246 | 78 | 0·236 | 46 | 0·193 | 160 | 0·281 | 42 | 0·133 | <0·0001 | 202 | 0·228 |

| Pneumonia‡ | 56 | 0·176 | 54 | 0·163 | 60 | 0·252 | 104 | 0·183 | 66 | 0·209 | 0·4008 | 170 | 0·192 |

| Diarrhoea | 39 | 0·123 | 32 | 0·097 | 33 | 0·139 | 27 | 0·047 | 77 | 0·244 | <0·0001 | 104 | 0·118 |

| Malaria | 23 | 0·072 | 43 | 0·130 | 22 | 0·093 | 32 | 0·056 | 56 | 0·177 | <0·0001 | 88 | 0·099 |

| Meningitis | 10 | 0·031 | 12 | 0·036 | 8 | 0·034 | 24 | 0·042 | 6 | 0·019 | 0·0721 | 30 | 0·034 |

| Nevirapine hypersensitivity§ | 1 | 0·003 | 16 | 0·048 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0·030 | 0 | 0 | 0·0021 | 17 | 0·019 |

| Growth faltering | 17 | 0·054 | 26 | 0·079 | 13 | 0·055 | 8 | 0·014 | 48 | 0·152 | <0·0001 | 56 | 0·063 |

| Rash | 2 | 0·006 | 3 | 0·009 | 1 | 0·004 | 6 | 0·011 | 0 | 0 | 0·0678 | 6 | 0·007 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0·006 | 4 | 0·012 | 2 | 0·008 | 3 | 0·005 | 5 | 0·016 | 0·1142 | 8 | 0·009 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 | 0·006 | 1 | 0·003 | 3 | 0·013 | 1 | 0·002 | 5 | 0·016 | 0·0150 | 6 | 0·007 |

| Death | 23 | 0·072 | 24 | 0·073 | 28 | 0·118 | 37 | 0·065 | 38 | 0·120 | 0·0070 | 75 | 0·085 |

Only p values less than 0·05 are specified.

Maternal antiretroviral vs no antiretroviral p value is 0·0337.

Maternal antiretroviral vs no antiretroviral p value is 0·0221.

Infant antiretroviral vs no antiretroviral p value is 0·0195.

Infant nevirapine antiretroviral vs no antiretroviral p value is 0·0007.

Throughout follow-up, only one maternal death occurred in the maternal-antiretroviral group (Kaplan-Meier estimate 0%), compared with eight in the other groups (1%; p=0.1261; table 4). Both the mother in the maternal-antiretroviral group (given lopinavir and ritonavir) and one mother who died in the infant-nevirapine group had increased baseline creatinine concentrations that should have precluded them from randomisation, an error that was reported to the institutional review boards; both deaths were due to renal failure. Two other deaths (one from presumed tuberculosis and the other of unknown cause) occurred in women not randomly assigned to the maternal-antiretroviral group but who had CD4 counts of less than 350 cells per μL and would have met the present guidelines for antiretroviral treatment in Malawi. The other five maternal deaths were due to tuberculosis (n=3), hepatic necrosis (n=1), and perforated viscus (n=1). The two maternal deaths before 28 weeks were from tuberculosis and hepatic necrosis. Risk of death was associated with a previous serious adverse event (p=0·0097). 229 women with CD4 counts of less than 250 cells per μL at 24 or 48 weeks after birth were referred for treatment: 64 in the maternal-regimen group, 97 in the infant-regimen group, and 68 in the control group.

Discussion

We have shown that maternal combination antiretroviral treatment or infant nevirapine prophylaxis during 28 weeks of breastfeeding reduces postnatal HIV transmission at 48 weeks compared with the baseline regimen of single-dose nevirapine and 7 days of zidovudine and lamivudine. The reduction at 48 weeks is lower than that at the end of the 28-week intervention phase (71% [95% CI 52–90] for infant nevirapine and 49% [22–77] for maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis).2

Four other randomised controlled trials have assessed either extended infant or maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis during breastfeeding compared with a control group of breastfeeding without additional antiretroviral prophylaxis to reduce postnatal transmission of HIV-1 (panel). Other than BAN, the only randomised trial that assessed three-drug maternal prophylaxis compared with a control group of breast-feeding without additional antiretroviral prophylaxis was Kesho Bora.28 From 34–36 weeks' gestation, researchers gave pregnant and breastfeeding women an antiretroviral regimen of zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir plus ritonavir until 6·5 months post partum.28 At 12 months, maternal prophylaxis significantly reduced the postnatal transmission rate, with a cumulative rate of 5% compared with 10% in the control group. In the Mma Bana study in Botswana,6 the rate of transmission was 1% at 6 months when maternal antiretroviral prophylaxis (zidovudine and lamivudine with either abacavir, or lopinavir and ritonavir) had been started antenatally. However, the study did not include a control group of breastfeeding women not given antiretroviral prophylaxis.6 By contrast with the results of the BAN study, these two investigations show that initiation of antenatal prophylaxis as early as possible has a greater effect on HIV transmission than does postnatal prophylaxis.

Three trials have assessed extended infant nevirapine compared with a control group of breastfeeding. SWEN8 was a combined analysis of three randomised trials of a regimen of daily nevirapine given to infants for 6 weeks after birth. At 6 months and 12 months of age, infant HIV transmission was not significantly reduced in the nevirapine group, suggesting that an extended duration of prophylaxis might be necessary.8,11 Investigators of PEPI9 assessed two different infant prophylaxis regimens (nevirapine or nevirapine plus zidovudine) for 14 weeks after birth. At 9 months of age, infant prophylaxis with either regimen significantly reduced postnatal HIV-1 infection, with an infection rate of 5% in children given nevirapine, 6% in those given the combination, and 11% in the control group.9 HPTN 04627 compared 6 weeks versus 6 months of daily infant nevirapine; 29% of the infants were born to women who had been on highly active antiretroviral treatment for their own health. HPTN showed that 2% of infants receiving 6 weeks of nevirapine and 1% of those receiving 6 months developed HIV between 6 weeks and 6 months.

In our trial, almost a third of cases of HIV-1 transmission occurred between 29 weeks and 48 weeks—a time when almost all mothers had reported that they had weaned their child. Although the benefits of breastfeeding and risks of early weaning in paediatric populations in resource-poor settings are well established, exclusive breastfeeding followed by rapid weaning at 6 months was generally believed to be the best strategy to balance the benefits of breastfeeding and risks of HIV transmission at the time of our study.29 Throughout our investigation, WHO recommended this strategy when formula feeding was not acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe.30 However, WHO now recommends that antiretroviral prophylaxis be given during the entire period of breastfeeding and against early weaning at 6 months, partly on the basis of data from the 28-week follow-up in BAN.1 The BAN study has drawn attention to the difficulty for HIV-infected women to comply with old breastfeeding cessation guidelines in low-resource settings, even in a trial offering individual and group counselling sessions and a nutritional supplement for weaning infants.31

We have also reported that early breastfeeding cessation is associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in infants exposed to HIV. The rate of serious adverse events in infants was significantly higher during the 29–48 week follow-up period than in the 28-week antiretroviral intervention phase. Some increased morbidity after 28 weeks is expected, because foods are introduced and infants begin to crawl. We cannot easily draw conclusions from comparisons of developmentally different periods without a study group in which infants continued breastfeeding from 6–12 months. Furthermore, because study visits were less frequent after 28 weeks, we had less opportunity to detect morbidity in the later stages than in the earlier study period.

However, our findings corroborate those from other studies of infants exposed to HIV showing that breast-feeding cessation is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality. The Zambia Exclusive Breastfeeding trial32,33 established that early, abrupt weaning at 4 months by HIV-infected mothers did not improve rate of infant HIV-free survival and was harmful to HIV-infected infants because it led to high rates of diarrhoeal illness between 4 months and 6 months. Two other reports34,35 showed that early cessation of breastfeeding was associated with increased risk of severe gastroenteritis in infants exposed to HIV compared with historical controls with prolonged breastfeeding. Early weaning also leads to poor growth36 and increased rates of all-cause mortality.35,37–39

During 48 weeks of follow-up in BAN, there were nine (0·4%) maternal deaths in 2369 randomly assigned mothers. Notably in BAN, eight of the nine maternal deaths were women not in the maternal-antiretroviral group, suggesting a possible benefit of providing breast-feeding mothers with antiretroviral therapy. In Kesho Bora,28 of 824 randomly assigned pregnant women (all with CD4 counts >200 cells per μL), four (1%) women assigned to the group given zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine and four (1%) given triple-antiviral drugs died within 12 months. In Mma Bana,6 of 560 women randomly assigned (all with CD4 counts >200 cells per μL) to combination antiretroviral therapy, only one (<1%) died within 6 months. The benefit of antiretroviral treatment to all HIV-infected breastfeeding women might be understated in our trial, which limited enrolment to post-partum women with CD4 counts greater than 250 cells per μL. Overall, these results are consistent with the evidence that early initiation of combination antiretroviral treatment could be advan tageous for adults who are neither pregnant nor breastfeeding.40,41

On the basis of findings from several studies,2–11,27,28 including BAN, WHO now recommends that HIV-positive mothers or uninfected infants receive antiretroviral prophylaxis during 12 months of breastfeeding.1,12 These revised recommendations, which represent a new framework for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, were largely a result of extrapolation of data from clinical trials that included shorter antiretroviral interventions. Although a clinical trial of extended infant prophylaxis is underway (PROMISE, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01061151) that will compare two infant regimens given for as long as 50 weeks of breastfeeding, no data are available from randomised trials of maternal or infant antiretroviral interventions lasting longer than 6 months.

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

We searched PubMed for reports published in any language before Feb 1, 2012, with the terms “breast feeding” or ”breastfeeding”, “HIV-1” or ”HIV”, “prevention”, and “randomized clinical trial” or “placebo-controlled trial”. We identified four other reports of randomised clinical trials that assessed either extended infant prophylaxis (SWEN,8 PEPI,9 HPTN 04627) or three-drug maternal prophylaxis (Kesho Bora28) during the period of breastfeeding compared with a control group of breastfeeding without additional antiretroviral prophylaxis to reduce postnatal transmission of HIV-1. These studies suggest that maternal or infant antiretroviral prophylaxis effectively reduces postnatal transmission of HIV-1 to the infant through breastfeeding and that reduction in risk increases with duration of prophylaxis. We identified no other studies of both infant and maternal prophylaxis.

Interpretation

Findings from several randomised trials now support the most recent guidance from WHO, recommending that antiretroviral drugs be given throughout breastfeeding to reduce postnatal HIV transmission. Our 48-week follow-up of women in Malawi has shown that either infant or maternal prophylaxis effectively reduces postnatal HIV-1 transmission and that this protective effect persists until after breastfeeding cessation. However, transmission does occur after mothers report that they have weaned their infants, so breastfeeding with prophylaxis for longer than 28 weeks might be advantageous. Infant morbidity and mortality also increased after 28 weeks; continued breastfeeding with prophylaxis given for an extended period could improve infant survival.

Acknowledgments

The BAN study was supported by grants from the Prevention Research Centers Special Interest Project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (SIP 13-01 U48-CCU409660-09, SIP 26-04 U48-DP000059-01, and SIP 22-09 U48-DP001944-01); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI50410); and the NIH Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (DHHS/NIH/FIC 2-D43 TW01039-06 and R24 TW007988; the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act). The antiretrovirals used were donated by Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Pharmaceuticals, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The Call to Action for the Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission programme was supported by the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, the United Nations Children's Fund, the World Food Program, the Malawi Ministry of Health and Population, Johnson and Johnson, and the US Agency for International Development. We thank all the women and their infants who agreed to participate in the study.

Footnotes

BAN study team Linda Adair, Yusuf Ahmed, Mounir Ait-Khaled, Sandra Albrecht, Shrikant Bangdiwala, Ronald Bayer, Margaret Bentley, Brian Bramson, Emily Bobrow, Nicola Boyle, Sal Butera, Charles Chasela, Charity Chavula, Joseph Chimerang'ambe, Maggie Chigwenembe, Maria Chikasema, Norah Chikhungu, David Chilongozi, Grace Chiudzu, Lenesi Chome, Anne Cole, Amanda Corbett, Amy Corneli, Anna Dow, Ann Duerr, Henry Eliya, Sascha Ellington, Joseph Eron, Sherry Farr, Yvonne Owens Ferguson, Susan Fiscus, Valerie Flax, Ali Fokar, Shannon Galvin, Laura Guay, Chad Heilig, Irving Hoffman, Elizabeth Hooten, Mina Hosseinipour, Michael Hudgens, Stacy Hurst, Lisa Hyde, Denise Jamieson, George Joaki (deceased), David Jones, Elizabeth Jordan-Bell, Zebrone Kacheche, Esmie Kamanga, Gift Kamanga, Coxcilly Kampani, Portia Kamthunzi, Deborah Kamwendo, Cecilia Kanyama, Angela Kashuba, Damson Kathyola, Dumbani Kayira, Peter Kazembe, Caroline C King, Rodney Knight, Athena P Kourtis, Robert Krysiak, Jacob Kumwenda, Hana Lee, Edde Loeliger, Dustin Long, Misheck Luhanga, Victor Madhlopa, Maganizo Majawa, Alice Maida, Cheryl Marcus, Francis Martinson, Navdeep Thoofer, Chrissie Matiki (deceased), Douglas Mayers, Isabel Mayuni, Marita McDonough, Joyce Meme, Ceppie Merry, Khama Mita, Chimwemwe Mkomawanthu, Gertrude Mndala, Ibrahim Mndala, Agnes Moses, Albans Msika, Wezi Msungama, Beatrice Mtimuni, Jane Muita, Noel Mumba, Bonface Musis, Charles Mwansambo, Gerald Mwapasa, Jacqueline Nkhoma, Megan Parker, Richard Pendame, Ellen Piwoz, Byron Raines, Zane Ramdas, John Rublein, Mairin Ryan, Ian Sanne, Christopher Sellers, Diane Shugars, Dorothy Sichali, Wendy Snowden, Alice Soko, Allison Spensley, Jean-Marc Steens, Gerald Tegha, Martin Tembo, Roshan Thomas, Hsiao-Chuan Tien, Beth Tohill, Charles van der Horst, Esther Waalberg, Elizabeth Widen, Jeffrey Wiener, Cathy Wilfert, Patricia Wiyo, Innocent Zgambo, and Chifundo Zimba.

Contributors DJJ, CSC, APK, LSA, FM, IH, and CvdH designed the trial. CSC, DK, MCH, DDK, SRE, SAF, GT, IAM, DSS, RJK, FM, ZK, AS, and IH collected data. MGH analysed data. DJJ, MGH, CCK, APK, JBW, LSA, CvdH interpreted data. DJJ wrote the report and had primary responsibility for final content. All authors reviewed versions of the report and contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest The University of North Carolina received grant support from Abbott Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. SAF received free diagnostic kits from Abbott, Roche, Gen-Probe, IQuum, and Perkin-Elmer; and has been a consultant for Alderon and on a scientific advisory board for Abbott, Roche, and Gen-Probe. SAF and MCH have received lecture fees from Abbott. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO . Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding: principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chasela CS, Hudgens MG, Jamieson DJ, et al. Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2271–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kilewo C, Karlsson K, Ngarina M, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding by treating mothers with triple antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: the Mitra Plus study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:406–16. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b323ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palombi L, Marazzi MC, Voetberg A, Magid NA. Treatment acceleration program and the experience of the DREAM program in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. AIDS. 2007;21(suppl 4):S65–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000279708.09180.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peltier CA, Ndayisaba GF, Lepage P, et al. Breastfeeding with maternal antiretroviral therapy or formula feeding to prevent HIV postnatal mother-to-child transmission in Rwanda. AIDS. 2009;23:2415–23. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ec20d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2282–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas TK, Masaba R, Borkowf CB, et al. Triple-antiretroviral prophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission through breastfeeding—the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study, Kenya: a clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Six Week Extended-Dose Nevirapine (SWEN) Study Team Extended-dose nevirapine to 6 weeks of age for infants to prevent HIV transmission via breastfeeding in Ethiopia, India, and Uganda: an analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2008;372:300–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumwenda NI, Hoover DR, Mofenson LM, et al. Extended antiretroviral prophylaxis to reduce breast-milk HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:119–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thior I, Lockman S, Smeaton LM, et al. Breastfeeding plus infant zidovudine prophylaxis for 6 months vs formula feeding plus infant zidovudine for 1 month to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission in Botswana: a randomized trial: the Mashi Study. JAMA. 2006;296:794–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omer SB, Six Week Extended-Dose Nevirapine Study Team Twelve-month follow-up of Six Week Extended Dose Nevirapine randomized controlled trials: differential impact of extended-dose nevirapine on mother-to-child transmission and infant death by maternal CD4 cell count. AIDS. 2011;25:767–76. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328344c12a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Horst C, Chasela C, Ahmed Y, et al. Modifications of a large HIV prevention clinical trial to fit changing realities: a case study of the Breastfeeding, Antiretroviral, and Nutrition (BAN) protocol in Lilongwe, Malawi. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moses A, Zimba C, Kamanga E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission: program changes and the effect on uptake of the HIVNET 012 regimen in Malawi. AIDS. 2008;22:83–87. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f163b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayira D, Bentley ME, Wiener J, et al. A lipid-based nutrient supplement mitigates weight loss among HIV-infected women in a factorial randomized trial to prevent mother-to-child transmission during exclusive breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:759–65. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration [(accessed Jan 19, 2012)];FDA public health advisory for nevirapine (viramune) http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051674.htm.

- 18.Chavula C, Long D, Mzembe E, et al. Stopping the control arm in response to the DSMB: mother's choice of HIV prophylaxis during breastfeeding in the BAN Study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO, UNICEF [(accessed Jan 19, 2012)];Breastfeeding counselling: a training course. 1993 http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/who_cdr_93_3/en/

- 20.Phuka JC, Gladstone M, Maleta K, et al. Developmental outcomes among 18-month-old Malawians after a year of complementary feeding with lipid-based nutrient supplements or corn-soy flour. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among children, adolescents and adults. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Division of AIDS [(accessed Jan 30, 2012)];Table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events, version 1.0—December 2004 (clarification August 2009) http://rsc.tech-res.com/Document/safetyandpharmacovigilance/Table_for_Grading_Severity_of_ Adult_Pediatric_Adverse_Events.pdf.

- 23.Emergency Nutrition Network [(accessed Jan 30, 2012)];Measuring malnutrition: individual assessment. 2011 May; http://www.ennonline.net/pool/files/ife/m6-measuring-malnutrition,-individual-assessment-fact-sheet.pdf.

- 24.Kerac M, Blencowe H, Grijalva-Eternod C, et al. Prevalence of wasting among under 6-month-old infants in developing countries and implications of new case definitions using WHO growth standards: a secondary data analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1008–13. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.191882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alioum A, Dabis F, Dequae-Merchadou L, et al. Estimating the efficacy of interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in breast-feeding populations: development of a consensus methodology. Stat Med. 2001;20:3539–56. doi: 10.1002/sim.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coovadia HM, Brown ER, Fowler MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of an extended nevirapine regimen in infant children of breastfeeding mothers with HIV-1 infection for prevention of postnatal HIV-1 transmission (HPTN 046): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:221–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61653-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kesho Bora Study Group Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:171–80. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fowler MG, Newell ML. Breast-feeding and HIV-1 transmission in resource-limited settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:230–39. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . New data on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and their policy implications: WHO Technical Consultation on Behalf of the UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/UNAIDS Inter-Agency Task Team on Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker ME, Bentley ME, Chasela C, et al. The acceptance and feasibility of replacement feeding at 6 months as an HIV prevention method in Lilongwe, Malawi: results from the BAN study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:281–95. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhn L, Aldrovandi GM, Sinkala M, et al. Effects of early, abrupt weaning on HIV-free survival of children in Zambia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:130–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fawzy A, Arpadi S, Kankasa C, et al. Early weaning increases diarrhea morbidity and mortality among uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers in Zambia. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1222–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onyango-Makumbi C, Bagenda D, Mwatha A, et al. Early weaning of HIV-exposed uninfected infants and risk of serious gastroenteritis: findings from two perinatal HIV prevention trials in Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:20–27. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bdf68e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kafulafula G, Hoover DR, Taha TE, et al. Frequency of gastroenteritis and gastroenteritis-associated mortality with early weaning in HIV-1-uninfected children born to HIV-infected women in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:6–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bd5a47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arpadi S, Fawzy A, Aldrovandi GM, et al. Growth faltering due to breastfeeding cessation in uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers in Zambia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:344–53. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homsy J, Moore D, Barasa A, et al. Breastfeeding, mother-to-child HIV transmission, and mortality among infants born to HIV-Infected women on highly active antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:28–35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bdf65a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhn L, Sinkala M, Semrau K, et al. Elevations in mortality associated with weaning persist into the second year of life among uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:437–44. doi: 10.1086/649886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Chen S, et al. Effects of cessation of breastfeeding in HIV-1-exposed, uninfected children in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:388–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]