Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine the predictive potential of multiple indicators (eg, preadmission scores, unit, module and clerkship grades, course and examination scores) on academic performance at medical school, with a view to identifying students at risk.

Methods

An analysis was undertaken of medical student grades in a 6-year medical school program at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, over the past 14 years.

Results

While high school scores were significantly (P < 0.001) correlated with the final integrated examination, predictability was only 6.8%. Scores for the United Arab Emirates university placement assessment (Common Educational Proficiency Assessment) were only slightly more promising as predictors with 14.9% predictability for the final integrated examination. Each unit or module in the first four years was highly correlated with the next unit or module, with 25%–60% predictability. Course examination scores (end of years 2, 4, and 6) were significantly correlated (P < 0.001) with the average scores in that 2-year period (59.3%, 64.8%, and 55.8% predictability, respectively). Final integrated examination scores were significantly correlated (P < 0.001) with National Board of Medical Examiners scores (35% predictability). Multivariate linear regression identified key grades with the greatest predictability of the final integrated examination score at three stages in the program.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that it may be possible to identify “at-risk” students relatively early in their studies through continuous data archiving and regular analysis. The data analysis techniques used in this study are not unique to this institution.

Keywords: at-risk students, grade predictability, scores

Introduction

Admission to medical school is generally hotly contested, with many more applicants than available places.1 Because medical training is resource-intensive, it is important to select students who are capable of developing into competent and safe doctors. The dilemma facing medical faculties, however, is which selection criteria best predict student “success.”2,3 Ultimately, success should represent physician competence,4–7 but this is a difficult task because many cognitive and noncognitive factors influence competence.1,6–9 Individual medical faculties thus often develop unique entrance criteria encompassing more than one domain. Despite the increasing use of nonacademic factors, such as attitude and empathy, in the selection process, preadmission academic achievement remains an important consideration.1 However, the evidence is conflicting in terms of the value of academic criteria, such as the secondary school grade, in terms of academic success at medical school, largely because of the variability in secondary school education.1,8,10

The admission process is only the beginning of a long journey to graduation. In line with a learner-centered philosophy, once accepted, students should be continuously monitored, so that those “at risk” at different stages of their studies can be identified, and the appropriate support and remediation provided.11,12 Identifying “at-risk” students becomes increasingly important in the context of widening access, as would be the case for promoting ethnic minorities or addressing previous political disadvantage.13–15 The situation at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, the only federal medical school in the United Arab Emirates, would certainly be considered a case of widening access. Established in the 1980s, the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences has a social responsibility to train Emirati doctors to service the national (Emirati) and expatriate United Arab Emirates communities. Since graduating its first Emirati doctors in 1994, student numbers have steadily increased in line with a national emiratization program. In recent years, this has culminated in the easing of some medical school entrance criteria, necessitating the identification of potentially “at-risk” students early and tracking their progress through their studies.

Institutional context

The Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences curriculum comprises three 2-year courses, ie, medical sciences, organ systems, and clinical sciences. During medical sciences, organ systems, and clinical sciences, students complete 10 units, 11 modules (including two clinical skills modules), and 10 clerkships, respectively (Table 1). There is continuous assessment over the 2-year period to determine eligibility for externally reviewed course examinations. During clinical sciences, students rotate through clerkships in internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, obstetrics and gynecology, community medicine, and family medicine (Table 1). The externally examined final integrated examination is the high-stakes licensing examination, comprising clinical (objective structured clinical examination, patient cases) and theory (inhouse, National Board of Medicine Examiners comprehensive clinical examination) components.

Table 1.

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences 6-year curriculum structure indicating units, modules, clerkships, course averages, and examinations in chronological order

| Medical sciences course year 1 (MSC1) | |

| Unit 1 | Introduction to medical sciences |

| Unit 2 | The cell |

| Unit 3 | The tissues |

| Unit 4 | Movement and metabolism |

| Unit 5 | The thorax |

| Medical sciences course year 2 (MSC2) | |

| Unit 6 | The abdomen |

| Unit 7 | Cellular communication |

| Unit 8 | Head and neck |

| Unit 9 | Molecular medicine |

| Unit 10 | Infection |

| Medical sciences course averages and examinations | |

| MSC1A | Medical sciences course 1 average |

| MSC2A | Medical sciences course 2 average |

| MSCA | Medical sciences course average (MSC1 and MSC2) |

| MSCE | Medical sciences course final examination |

| Organ systems course year 1 (OSC1) | |

| CSM1 | Clinical skills 1 |

| Module 1 | Hematology/immunology |

| Module 2 | Cardiovascular system |

| Module 3 | Respiratory system |

| Module 4 | Gastrointestinal system |

| Module 5 | Musculoskeletal system |

| Organ system course year 2 (OSC2) | |

| CSM2 | Clinical skills 2 |

| Module 6 | Endocrine and metabolism |

| Module 7 | Urogenital and reproduction |

| Module 8 | Neurosciences and special senses |

| Module 9 | Behavioral sciences |

| Organ systems course averages and examinations | |

| OSC1A | Organ systems course 1 average |

| OSC2A | Organ systems course 2 average |

| OSCA | Organ systems course average (OSC1 and OSC2) |

| OSCE | Organ systems course final examination |

| Clinical sciences course year 1 (CSC1) | |

| Clerk 1 | Internal medicine 1 |

| Clerk 2 | Surgery 1 |

| Clerk 3 | Pediatrics 1 |

| Clerk 4 | Psychiatry |

| Clerk 5 | Obstetrics and gynecology |

| Clinical sciences course year 2 (CSC2) | |

| Clerk 6 | Internal medicine 2 |

| Clerk 7 | Surgery 2 |

| Clerk 8 | Pediatrics 2 |

| Clerk 9 | Community medicine |

| Clerk 10 | Family medicine |

| Clinical sciences course averages and examinations | |

| CSC1A | Clinical sciences 1 course average |

| CSC2A | Clinical sciences 2 course average |

| ORAV | Overall medical school average (all units, modules, clerkships) |

| FIE | Final integrated examination |

All applicants to the English medium Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences medical program are Emirati nationals (Arabic speakers) who attended either a public (Arabic medium) or a private (English medium) secondary school and who successfully completed a general university foundation year. Final selection depends on a student’s high school grade, a satisfactory international English examination score, a Medical College Admission Test, and an interview. Despite these selection criteria, there is a small annual attrition, and a number of students are considered “at-risk” or borderline at different stages of the program. Therefore, the present exploratory study set out to analyze historic data to identify potential predictors of success in the final integrated examination and whether there were points in the curriculum where “at-risk” students could be identified, such that support and remediation can be provided.

Two main research questions were posed in this study, ie, the extent to which available preadmission grades (including English) predict performance (or lack thereof) during the 6-year medical program, and which scores during a student’s medical studies best predict performance (or lack thereof) during the 6-year program.

Methods

Database queries of all available student grades from high school and university medical studies were conducted. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Al Ain Medical District human research ethics committee. Preadmission grades were high school grades, the United Arab Emirates University placement assessment, which is the common educational proficiency assessment (comprising English and mathematics), and an international English examination (eg, TOEFL® or the International English Language Testing System). In addition, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences grades comprise results from units, modules and clerkships; year averages, as well as end of course examinations, final integrated examination, and National Board of Medicine Examiners results. Analyses were performed on three data sets:

Ten cohorts of medical students for whom comprehensive grades were available from high school to graduation (n = 297)

All Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences grades (unit, module, clerkships, year averages, course examinations) to determine their predictive ability for all components of the program

A multivariate linear regression of grouped grades for the first 2 years (medical sciences), the first four years (medical sciences and organ systems), and in the 6-year curriculum (medical sciences, organ systems, and clinical sciences) to determine components of the program that offer the greatest predictability of the final integrated examination grade.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation (r) with a statistical significance level of P < 0.01 was used to identify significant correlations between grades. R2 was used to identify the level of variability in performance explained by the predicting variable (predictability). R2 values range between 0 and 1, with values close to 0 indicating low predictability and values close to 1 indicating high predictability. R2 values can also be depicted as percent predictability,16–18 which, for the purposes of this study, have been categorized as: >60% high predictability; 40%–60% moderate predictability; and <40% as low predictability.

Results

The total number of students for the 14-year study period was 792 (228 males, 564 females), with the average graduating cohort comprising 32 students (10 males, 22 females). Because the Common Educational Proficiency Assessment, TOEFL, and the International English Language Testing System were introduced in the 2000/2001 academic year only, these scores were not available for some students. Some grades for the currently enrolled students (ie, 2005–2010 intakes) were also not available.

Grades available on admission

Although significant correlations were measured for the three preadmission grades (high school grade, Common Educational Proficiency Assessment, English), predictability was low in the short and long term (Table 2). The high school grade best predicted performance in unit 1 (13.8%). Common Educational Proficiency Assessment and English language grades generally did not predict performance.

Table 2.

Predictability (percent) of various preadmission criteria and selected program grades (darker background indicates higher predictability)

| HSG | CEPA | IELTS | Unit1 | Unit10 | MSCE | OSCA | OSCE | CSC2A | ORAV | FIE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSG | ] 0.0 | ] 0.0 | ] 13.8 | ] 6.3 | ] 8.6 | ] 8.5 | ] 9.4 | ] 11.3 | ] 13.5 | ] 6.8 | |

| CEPA | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 16.0 | 14.9 | |

| IELTS | 0.0 | 0.8 | 6.2 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 20.4 | 13.9 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Unit1 | 13.8 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 24.6 | 26.4 | 21.8 | 18.1 | 14.6 | 31.8 | 16.6 | |

| Unit2 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 35.5 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 26.3 | 17.7 | 7.7 | 27.9 | 7.2 |

| Unit3 | 6.4 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 36.4 | 36.8 | 31.5 | 30.4 | 15.1 | 13.5 | 30.7 | 12.9 |

| Unit4 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 15.3 | 41.1 | 34.5 | 35.8 | 24.5 | 12.4 | 38.4 | 12.7 |

| Unit5 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 4.5 | 33.4 | 37.9 | 52.1 | 44.2 | 33.2 | 17.3 | 47.3 | 19.6 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Unit6 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 45.4 | 44.6 | 43.4 | 28.0 | 20.5 | 42.0 | 12.0 |

| Unit7 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 7.2 | 58.4 | 28.9 | 34.7 | 20.8 | 19.4 | 30.7 | 14.0 |

| Unit8 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 25.8 | 52.0 | 49.3 | 49.7 | 30.1 | 28.7 | 51.0 | 21.9 |

| Unit9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 61.6 | 48.0 | 49.6 | 23.6 | 20.7 | 47.5 | 12.5 |

| Unit10 | 6.3 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 24.6 | 55.8 | 67.1 | 40.3 | 35.9 | 64.0 | 38.1 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| MSC1A | 10.1 | 0.1 | 4.0 | 50.8 | 48.9 | 48.7 | 45.8 | 33.9 | 17.4 | 53.4 | 19.1 |

| MSC2A | 8.6 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 39.6 | 72.9 | 65.9 | 66.6 | 43.7 | 30.4 | 74.1 | 26.6 |

| MSCA | 10.2 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 49.0 | 62.9 | 59.3 | 57.9 | 40.3 | 24.3 | 65.9 | 23.6 |

| MSCE | 8.6 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 26.4 | 55.8 | 59.3 | 39.4 | 26.9 | 69.4 | 21.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| CSM1 | 14.7 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 21.2 | 8.8 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 20.9 | 29.9 | 33.9 | 23.7 |

| Mod1 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 16.3 | 54.2 | 46.0 | 71.2 | 42.1 | 21.1 | 52.7 | 16.1 |

| Mod2 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 17.6 | 44.1 | 44.5 | 67.6 | 39.8 | 18.8 | 54.3 | 19.5 |

| Mod3 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 16.6 | 36.1 | 39.4 | 61.8 | 41.2 | 21.7 | 51.7 | 17.7 |

| Mod4 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 50.8 | 37.0 | 69.4 | 43.7 | 35.3 | 56.4 | 25.1 |

| Mod5 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 14.1 | 42.9 | 36.8 | 65.0 | 42.0 | 26.8 | 53.7 | 23.5 |

|

| |||||||||||

| CSM2 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 0.7 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 18.1 | 20.3 | 26.6 | 31.1 | 31.8 | 26.9 |

| Mod6 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 41.2 | 27.9 | 51.3 | 28.7 | 21.9 | 37.0 | 12.5 |

| Mod7 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 10.4 | 36.2 | 30.9 | 54.6 | 46.4 | 27.4 | 53.3 | 25.0 |

| Mod8 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 10.7 | 48.4 | 33.1 | 67.7 | 48.9 | 26.3 | 56.0 | 27.2 |

| Mod9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 9.5 | 31.6 | 16.7 | 31.8 | 23.5 | 19.2 | 33.2 | 22.4 |

|

| |||||||||||

| OSC1A | 8.1 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 23.8 | 62.6 | 59.8 | 97.4 | 61.2 | 37.1 | 80.6 | 30.8 |

| OSC2A | 7.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 19.2 | 65.8 | 55.7 | 97.2 | 65.8 | 41.9 | 85.4 | 35.3 |

| OSCA | 8.5 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 21.8 | 67.1 | 59.3 | 64.8 | 40.2 | 84.8 | 34.0 | |

| OSCE | 9.4 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 18.1 | 40.3 | 39.4 | 64.8 | 34.6 | 73.8 | 41.0 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Clerk1 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 19.7 | 7.9 | 19.9 | 18.1 | 16.5 | 32.4 | 14.1 |

| Clerk2 | 6.4 | 13.5 | 0.5 | 13.0 | 23.8 | 19.9 | 30.4 | 30.3 | 28.4 | 47.6 | 34.2 |

| Clerk3 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 19.7 | 18.1 | 29.7 | 33.5 | 35.4 | 39.3 | 25.4 |

| Clerk4 | 8.1 | 20.3 | 2.0 | 11.6 | 25.4 | 18.5 | 32.6 | 29.5 | 36.2 | 43.6 | 36.2 |

| Clerk5 | 1.4 | 13.8 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 18.7 | 10.6 | 21.6 | 21.1 | 39.2 | 31.9 | 26.9 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Clerk6 | 7.8 | 1.9 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 21.4 | 24.0 | 25.0 | 23.0 | 46.5 | 37.2 | 33.9 |

| Clerk7 | 0.0 | 17.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 6.9 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 8.5 | 14.2 | 15.8 | 12.3 |

| Clerk8 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 23.0 | 15.5 | 25.1 | 26.0 | 39.2 | 34.7 | 28.2 |

| Clerk9 | 8.2 | 4.8 | 18.7 | 6.5 | 31.1 | 20.1 | 28.1 | 25.6 | 39.3 | 37.1 | 25.3 |

| Clerk10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 3.8 | 17.6 | 12.7 | 29.9 | 18.9 | 11.0 |

|

| |||||||||||

| CSC1A | 4.5 | 11.7 | 0.1 | 8.4 | 33.5 | 22.9 | 43.2 | 43.0 | 45.8 | 65.4 | 48.6 |

| CSC2A | 11.3 | 0.6 | 5.9 | 14.6 | 35.9 | 26.9 | 40.2 | 34.6 | 56.4 | 43.2 | |

| ORAV | 13.5 | 16.0 | 20.4 | 31.8 | 64.0 | 69.4 | 84.8 | 73.8 | 56.4 | 55.8 | |

| FIE | 6.8 | 14.9 | 13.9 | 16.6 | 38.1 | 21.2 | 34.0 | 41.0 | 43.2 | 55.8 | |

| NBME | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 43.0 | 21.0 | 4.4 | 14.7 | 23.7 | 10.8 | 27.7 | 35.0 |

Abbreviations: HSG, high school grade; CEPA, Common Educational Proficiency Assessment; IELTS, International English Language Testing System. The remainder of the abbreviations used in this table are listed in Table 1.

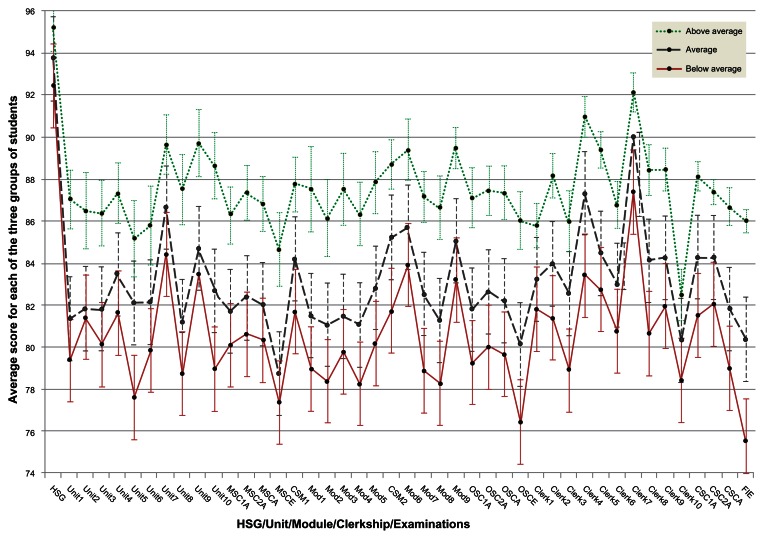

Above average, average, and below average students

For the 10 cohorts for which comprehensive grades were available, students were categorized into the “above average” (top 20th percentile), “average” (middle 60th percentile), and “below average” (bottom 20th percentile, Figure 1). However, it is important to note that the average does not represent the same students in each group. Apparent from Figure 1 is the variability of grades for different program components. Of interest is the spread of unit 1 results following the high school grade clustering and the components that discriminate between the above average, average, and below average groups, in terms of the final integrated examination scores (eg, unit 5, unit 10, medical sciences examination, module 8, organ systems examination, clinical sciences year averages). These data were analyzed further.

Figure 1.

Profile of above average (top 20th percentile), average (middle 60th percentile,) and below average (bottom 20th percentile) grades for students for whom all scores were available from the high school grade to the final integrated examination (n = 297).

Abbreviations: The abbreviations used in this figure are shown in Table 1.

Medical school grades during the six-year program

Table 2 suggests that a student’s performance in the introductory unit, ie, unit 1, may be an early indicator of subsequent performance during medical sciences, with predictability being 51% for the medical sciences year 1 average, 40% for the medical sciences year 2 average, and 26% for the medical sciences examination. Similarly, unit 10 and the medical sciences examination are identified as moderate predictors of performance in many organ systems modules and high predictors of organ systems averages.

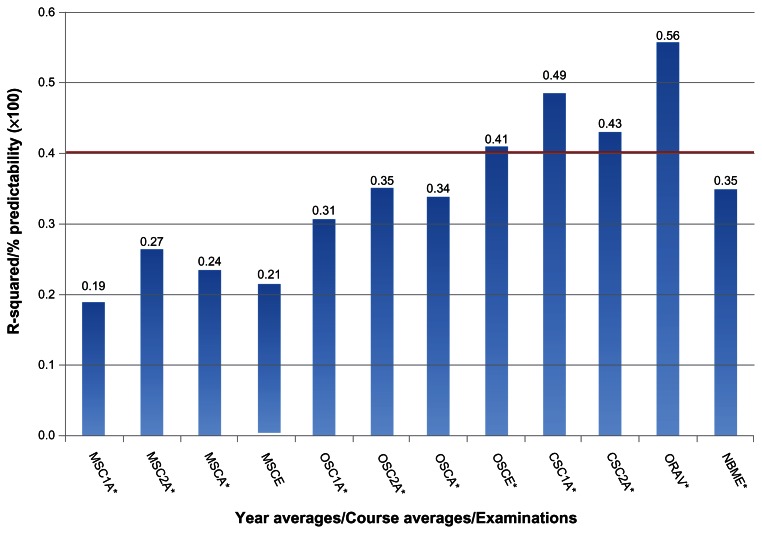

Medical sciences, organ systems, and clinical sciences examination grades were significantly correlated with the average scores for the 2-year period comprising the course (59%, 65%, 56% predictability; P < 0.05, 0.001, 0.001; n = 415, 321, 244, respectively). The averages for year 1 and year 2 of medical sciences or organ systems were significantly correlated (P < 0.001), with high predictability, ie, 83.2% for medical sciences (n = 514) and 89.9% for organ systems (n = 396). The predictability of the clinical sciences year 1 average for the clinical sciences year 2 average was lower at 45.8% (P < 0.001, n = 283).

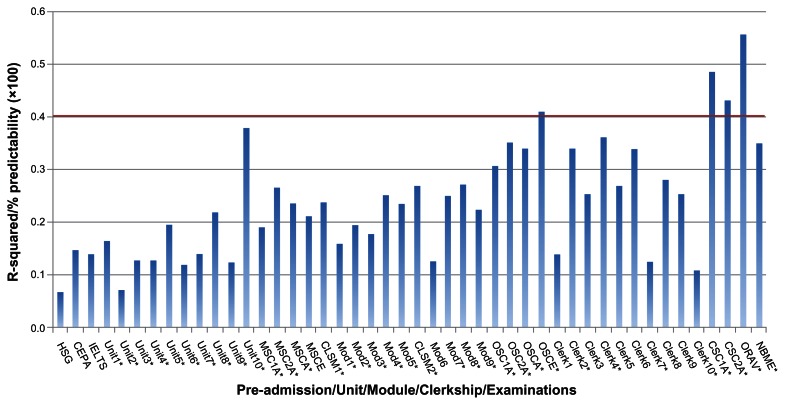

Medical school grades and final integrated examination success

Figure 2 confirms the potential value of some grades identified in Figure 1. To this end, unit 10 (38% predictability), the organ systems examination (41%), clinical sciences year 1 average (49%), clinical sciences year 2 average (43%), overall medical school average (56%), and the National Board of Medicine Examiners examination grade (35%) offered the greatest predictability of final integrated examination success.

Figure 2.

Predictability of preadmission grades and all medical school grades for the final integrated examination.

Notes: *P = 0.01; 40%–60%, moderate predictability; <40%, low predictability.

Abbreviations: The abbreviations used in this figure are shown in Table 1.

Because year averages determine whether a student qualifies for the course examination, and the course examinations determine a student’s progression to the next phase, their predictive ability warrants consideration. Predictability for the final integrated examination increased from the medical sciences averages and examinations (19%–27%), through organ systems (31%–35%) to clinical sciences grades (43%–49%, n = 242). The overall medical school average, available one month before the final integrated examination, accounted for the greatest predictability (56%, P < 0.001, n = 245). Final integrated examination grades were also significantly correlated (35% predictability, P < 0.001, n = 154) with the National Board of Medicine Examiners clinical sciences examination scores.

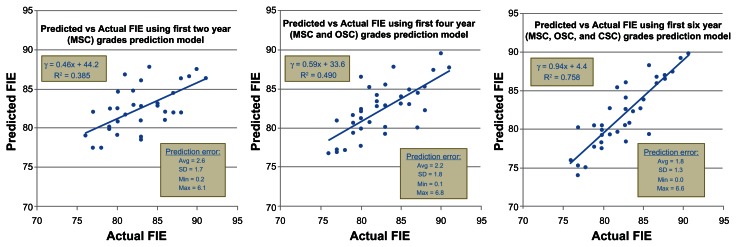

Multiple regression modeling

Having identified individual grades, grade averages, and course examinations as potential predictors of the final integrated examination results, the next undertaking was a stepwise multivariate linear regression (adjusted R2) using three sets of grades (all medical sciences grades, all medical sciences and organ systems grades, all six-year grades). All final integrated examination marks available up to, but not including, the 2009/2010 academic year were included. The analysis identified the following:

First 2 year (medical sciences) grades: unit 10 and medical sciences course final examination in order of predictive value were identified as key grades (out of 15 grades) providing 40.5% predictability of the final integrated examination (n = 128).

First 4 year (medical sciences and organ systems) grades: OSC Average, unit 10, and clinical skills year 2 in order of predictive value were identified as key grades (out of 30 grades) providing 53.3% predictability of the final integrated examination (n = 122).

6 year grades (medical sciences, organ systems, and clinical sciences): overall medical school average, organ systems year 1, medical sciences course final examination, organ systems course final examination, unit 9, MSC Average, organ systems year 2, clerk 3, and clerk 6 in order of predictive value were identified as key grades (out of 44 grades) providing 79.9% predictability of the final integrated examination (n = 119).

When the model was tested comparing the actual versus predicted 2009/2010 final integrated examination grades, the average predictive error decreased from 2.6 marks, 4 years before the final integrated examination, to 2.2 marks, 2 years before the final integrated examination, with 1.8 marks in average predictive error a month prior to the final integrated examination (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Regression analysis model: Predicted versus actual final integrated examination grade using 2009–2010 grades.

Abbreviations: FIE, final integrated examination; MSC, medical sciences course; OSC, organ systems course; CSC, clinical sciences course.

Summary of results

Based on the findings of this study, unit 1 (the first learning encounter in the program) can be used to identify struggling students early

The medical sciences year 1 average is a useful indicator of performance in medical sciences year 2

Unit 10 (end of medical sciences year 2) may be a key indicator of performance in subsequent years, including the overall average 4 years later

Organ systems average and organ systems examination grades appear to be useful indicators of performance 2 years in advance of the final exit examination

Regression analysis identified key components within the program that are highly associated with final exit examination success, allowing for prediction of performance well in advance of this final exit examination

Graphic depiction of data, such as Figure 1, allows one to identify anomalies in curriculum components (eg, poor discriminators of student performance, excessively high or low summative assessment).

Discussion

This exploratory study set out to investigate the potential predictive ability of preadmission grades and various summative assessment results during a 6-year medical program, with the view to identifying “at-risk” students early and at different stages of their studies. Although we did not find the “smoking gun,” ie, a single predictor of long-term student performance, we believe that this study has highlighted a number of important issues in terms of admission criteria, curriculum components that require attention, and possible remediation points during the 6-year program.

With regard to the predictive ability of preadmission grades (high school grade, English, Common Educational Proficiency Assessment), unlike some reports of the usefulness of the high school grade during medical studies and beyond,2,6,19,20 the present study found that the high school grade, a major Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences admission criterion, is a poor predictor of performance, even in the short term. This may reflect the high school grade cutoff (>90%) and hence the low discriminatory power. Because there is evidence suggesting that premedical school science may be correlated with success at medical school,1,2 individual mathematics, biology, or other science grades may be more appropriate as potential predictors than the comprehensive high school grade.

The low correlation of English language scores with other grades was surprising, because much has been written about the difficulties of studying medicine as an English second language learner.22–28 A recent study of the transferable skills of incoming Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences medical students who were followed up a year later, suggest that language is a barrier to academic achievement.29 Like the high school grade, the low predictability of English and future performance may lie in its poor discriminatory power because applicants generally just meet the minimum requirement (500 for TOEFL, 5 for the International English Language Testing System). Notwithstanding this result, we believe that English language proficiency does influence success in the early years of medical studies. The next step is to consider the predictive ability of different components of the International English Language Testing System (ie, listening, speaking, reading, writing).

Because it is unlikely that United Arab Emirates secondary schooling will be standardized in the foreseeable future, alternative selection criteria need to be considered. Admission tests, such as the Medical College Admission Test, which probably offer greater objectivity than the high school grade, are regularly used elsewhere in the admission process. Although Lynch et al found that the UK Clinical Aptitude Test failed to predict year 1 performance at two medical schools,10 the US Medical College Admission Test predicted performance in all three US Medical Licensing Examination steps.21 In the early years of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences medical program (ie, in the 1990s), Abdulrazzaq et al found that the grade point average, a measure of overall medical school performance, was significantly correlated with an admission test.3 In recent years, the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences admission process has included a Medical College Admission Test-type examination but, because the results are not archived electronically, they could not be used for this study.

Having admitted students with variable secondary schooling and English language proficiency, features common to many medical schools, the next task is to identify curriculum components that predict performance early in the program, at different stages and, ultimately, in the final licensing examination and beyond graduation.3,4,6 Although our analysis did not yield a single predictor, it has been possible to identify different points in the program where borderline students can be flagged. To this end, the first 6-week unit (introduction to medical sciences), with reasonable predictability for medical sciences year averages and the course examination, is suitable for identifying struggling students at the outset of their studies. Based on our experiences this past year, with a large number of underprepared students in terms of language and maturity, unit 1 is currently being restructured such that students are provided with extra language and study skills support as they get to grips with the fundamentals of chemistry, medical biology, and physics.

For early identification of “at-risk” students, stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis added value in that the predictive power of this model in terms of predicting success in the final exit examination exceeded that of any individual curriculum component. This translated into 40.5% predictability 4 years in advance of the final integrated examination, 53.3% predictability 2 years in advance, and 79.9% predictability a month before the final integrated examination. At each stage, students could be flagged and supported with remediation and then tracked for progress.

In undertaking such a comprehensive analysis, the correlation between two curriculum components may not always be explicable. For example, Kozar et al,30 while attempting to identify students at risk of failing year 4 National Board of Medicine Examiners surgery, found that the apparently unrelated year 2 pathology was the best predictor of success for this examination. In the present study, the moderate (42% predictability) of unit 1 for the final National Board of Medicine Examiners clinical sciences examination almost 6 years later is difficult to explain, but warrants further investigation. It may be that the long vignettes in the National Board of Medicine Examiners require a good command of English, as well as critical thinking skills. Successful students in unit 1 may therefore be individuals with higher English and/or higher order cognitive abilities.

Although this study began as an exploratory exercise of analyzing 14 years of data to ascertain the predictive value of various summative assessments, the analysis yielded some unanticipated benefits. To this end, certain curriculum components should be investigated, eg, the exceptionally high grades for clerkship 2 (surgery year 1) while clerkship 10 (family medicine) appears not to discriminate between the performance of below average, average, and above average students. The significant correlation between the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences course examinations and the National Board of Medicine Examiners examination is encouraging, suggesting that in the cognitive domain, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences students’ achievements may be comparable with an international benchmark.

While this study reflects the situation at one medical school, the principles are generalizable. We hope that readers recognize the long-term and short-term benefits of electronic data archiving of all student grades. Archiving allows the generation of regular snapshots of summative assessments to ensure that a degree of uniformity of results exists. More importantly, as this study has shown, it allows medical educators to identify “at-risk” students at key points in the program such that remediation can be undertaken. The earlier such students can be flagged, the more likely these will be a positive outcome. We believe that we can do this as early as the first 6 weeks of our program, but certainly within the first 2 years.

Conclusion

Ideally, any medical educator would like to identify students requiring remediation at the earliest possible stage. With the variability in secondary schooling in most countries, the preadmission grades may not offer any discriminatory power in predicting performance during medical school. Medical schools thus need to make maximum use of data collected before and during the program. The data analysis techniques used in this study are not unique to this institution. Provided medical schools continuously archive summative assessment grades electronically, a faculty or support staff member familiar with database queries could perform such analyses and generate similar reports. We believe that this study has demonstrated that through continuous data archiving and regular analysis, it may be possible to identify “at-risk” students relatively early in their studies. As Hamdy et al7 point out in their best evidence medical education review, the literature on the long-term predictive value of undergraduate assessment systems is relatively sparse and warrants attention. From the exploratory findings of the present study, while long-term prediction (ie, over 6 years) may be difficult, there is educational merit in identifying grades that offer better short-term predictability. We are relatively confident of identifying “at-risk” students 4 years in advance of the final exit examination but more confident 2 years in advance. In both instances, there is sufficient time to support, remediate, and monitor students as they progress through their studies. Unlike most medical schools, where the annual intake exceeds 150 students, cohorts at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences are small but increasing. Notwithstanding, we believe that, in view of the 14-year period of data collection, the trends that have been identified are a true reflection of future students’ performances at Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Figure 3.

Predictability of year averages and course examinations for the final integrated examination.

Notes: *P = 0.01; 40%–60%, moderate predictability; <40%, low predictability.

Abbreviations: The abbreviations used in this figure are shown in Table 1.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and the University General Requirements Unit Student Records departments for providing us with the data used in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.James D, Chilvers C. Academic and non-academic predictors of success on the Nottingham undergraduate medical course 1970–1995. Med Educ. 2001;35:1056–1064. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Nasir FA, Robertson AS. Can selection assessments predict students’ achievements in the premedical year? A study at Arabian Gulf University. Educ Health (Arbingdon) 2001;14:277–286. doi: 10.1080/13576280110056618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdulrazzaq YM, Ibrahim K. Could final year school grades suffice as a predictor for future performance? Med Teach. 1993;15:243–251. doi: 10.3109/01421599309006718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veloski J, Herman MW, Gonnella JS, Zeleznik C, Kellow WF. Relationships between performance in medical school and first postgraduate year. J Med Educ. 1979;54:909–916. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonnella J, Hojat M. Relationship between performance in medical school and postgraduate competence. Med Educ. 1983;58:679–685. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumb AB, Vail A. Comparison of academic, application form and social factors in predicting early performance on the medical course. Med Educ. 2004;38:1002–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamdy H, Prasad K, Anderson MB, et al. BEME systematic review: Predictive values of measurements obtained in medical schools and future performance in medical practice. Med Teach. 2006;28:103–116. doi: 10.1080/01421590600622723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McManus IC, Smithers E, Partridge P, Keeling A, Fleming PR. A levels and intelligence as predictors of medical careers in UK doctors: A 20 year prospective study. BMJ. 2003;327:139–142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7407.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeAngelis S. Noncognitive predictors of academic performance. Going beyond the traditional measures. J Allied Health. 2003;32:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch B, MacKenzie R, Dowell J, Cleland J, Prescott G. Does the UKCAT predict year 1 performance in medical school. Med Educ. 2009;43:1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean M, Gibbs TJ. Learner-centred medical education: Improved learning or increased stress? Educ Health (Abingdon) 2009;22:287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean M, Gibbs T. Twelve tips to designing and implementing a learner-centred curriculum: Prevention is better than cure. Med Teach. 2010;32:225–230. doi: 10.3109/01421591003621663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes D. Eight years’ experience of widening access to medical education. Med Educ. 2002;36:979–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James D, Ferguson E, Powis D, Symonds I, Yates J. Graduate entry to medicine: Widening academic access and socio-economic access. Med Educ. 2008;42:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Wyk JM, McLean M, Futre EM. Using evaluation in a problem-based learning curriculum to promote transformation. Review of Further and Higher Education and Training. 2007;1:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peat J, Barton B. Medical Statistics: A Guide to Data Analysis and Critical Appraisal. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wikipedia. Coefficient of determination. [Accessed December 20, 2010.]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R-square.

- 18.Upshur REG, Moineddin R, Crighton E, Kiefer L, Mamdani M. Simplicity within complexity: seasonality and predictability of hospital admissions in the province of Ontario 1988–2001, a population-based analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haidinger G, Frischenschlager O, Mitterauer L. Prediction of success in the first-year exam in the study of medicine – a prospective survey. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117:827–832. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0477-x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haidinger G, Frischenschlager O, Mitterauer L. Reliability of predictors of study success in medicine. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;156:416–420. doi: 10.1007/s10354-006-0275-8. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julian ER. Validity of the medical college admission test for predicting medical school performance. Acad Med. 2005;80:910–917. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed B, Ahmed BL, Al-Jouhari MM. Factors determining the performance of medical students in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kuwait. Med Educ. 1988;22:506–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chur-Hansen A. Language background, proficiency in English, and selection for language development. Med Educ. 1997;31:312–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chur-Hansen A, Vernon-Roberts J. Clinical teachers’ perceptions of medical students’ English language proficiency. Med Educ. 1998;32:351–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhaliwal G. Teaching medicine to non-English speaking background learners in a foreign country. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:771–773. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0967-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassan MO, Gumaa KA, Harper A, Heseltine GFD. Contribution of English language to the learning of basic medical science in Sultan Qaboos University. Med Teach. 1995;17:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes SC, Farnill D. Medical training and English language proficiency. Med Educ. 1993;27:6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas P, Lenstrup M, Prinz J, Williamson D, Yip H, Tipoe G. Language as a barrier to the acquisition of anatomical knowledge. Med Educ. 1997;31:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLean M, Shaban S, Murdoch-Eaton D. Generic skills development early in the undergraduate medical curriculum: What does student self-assessment tell us? (In preparation) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozar RA, Kao LS, Miller CC, Schenarts KD. Preclinical predictors of surgery NBME exam performance. J Surg Res. 2007;140:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]