Abstract

Background

The effect of peer-led training in basic life support (BLS) in the education of medical students has not been assessed.

Subjects and methods

This study was a randomized controlled trial with a blinded outcome assessor. A total of 74 fourth-year medical students at Ehime University School of Medicine, Japan were randomly assigned to BLS training conducted by either a senior medical student (peer-led group) or a health professional (professional-led group). The primary outcome measure was the percentage of chest compressions with adequate depth (38–51 mm) by means of a training mannequin evaluated 20 weeks after BLS training. Secondary outcome measures were compression depth, compression rate, proportion of participants who could ensure adequate compression depth (38–51 mm) and adequate compression rate (90–110/minute), and retention of BLS knowledge as assessed by 22-point questionnaire.

Results

Percentage chest compressions with adequate depth (mean ± SD) was 54.5% ± 31.8% in the peer-led group and 52.4% ± 35.6% in the professional-led group. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of difference of the means was −18.7% to 22.8%. The proportion of participants who could ensure an adequate mean compression rate was 17/23 (73.9%) in the peer-led group but only 8/22 (36.4%) in the professional-led group (P = 0.011). On the 22-point questionnaire administered 20 weeks after training, the peer-led group scored 17.2 ± 2.3 whereas the professional-led group scored 17.8 ± 2.0. The 95% CI of difference of the means was −1.72 to 0.57.

Conclusion

Peer-led training in BLS by medical students is feasible and as effective as health professional-led training.

Keywords: basic life support, education, training, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Providing basic life support (BLS) is an essential skill for the survival of a patient after cardiac arrest. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, one of the important skills in BLS, is associated with increased chances of survival with a twofold increase in survival rate.1 With more people trained in BLS, more lives can potentially be saved; however, the high cost in terms of time, money, and opportunity of traditional training programs limits the number of citizens trained to perform BLS.

Employing medical students as instructors could help increase the number of people with BLS skills. Several studies showed that medical students could successfully teach BLS to lay people.2–4 Their teaching skills and the training outcome, however, were poorly evaluated.

Peer teaching and learning5 is a potentially effective method in medical education. Peer-led training in BLS by pairing senior and junior healthcare students can provide BLS skills of equally good quality as that provided by professional-led training.6,7 The Japanese system of medical education, however, is focused on education in a paternalistic manner.8 Although the concept of peer-led training in BLS is not new,9 arguments against peer teaching and learning by medical students are still common in Japan.

Therefore we conducted a study to compare peer-led training versus health professional-led training in a randomized controlled trial. The primary aim of our study was to determine whether medical students could offer a level of training comparable with that provided by experts.

Subjects and methods

Study design and participants

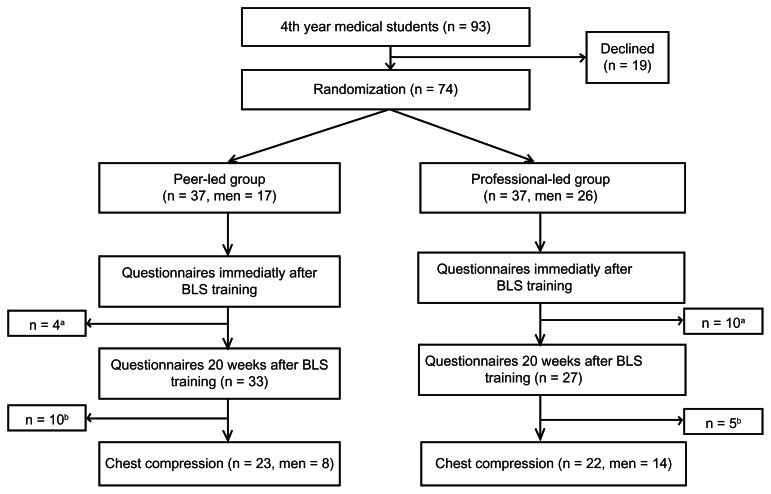

From April to May 2009, we conducted a randomized controlled trial approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ehime University School of Medicine. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants in the trial. We recruited fourth-year medical students attending an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) curriculum at Ehime University School of Medicine. None of the participants had prior BLS training. After the study aims were explained, the participants, who provided written informed consent, were allocated according to a Latin square design to either of the following two groups: one group instructed by senior medical students (peer-led group) and the other group instructed by healthcare professionals (professional-led group).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through trial.

Notes:aDid not return for evaluation 20 weeks after basic life support (BLS) training. bDeclined evaluation. The data are presented as means ± standard deviation.

Intervention (training)

Two-hour BLS training was conducted according to American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines.10 One instructor taught three or four participants with a training mannequin and a training video (BLS for Healthcare Providers Video by AHA). The peer instructors were nine volunteers (five fifth-year and four sixth-year students) recruited from a student- run group interested in BLS. All had undergone BLS training in their fourth year and passed the OSCE. Six (three fifth-year students and three sixth-year students) had completed the Immediate Cardiac Life Support (ICLS) course sponsored by Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (http://www.icls-web.com/index.html). The professional instructors were 7 emergency medical technicians, 2 anesthesiologists, and 2 nurses. The emergency medical technicians and nurses had completed the ICLS course; the anesthesiologists had completed the BLS provider course.

Outcome measurements

We assessed BLS skills with the Laerdal Skill Reporter Resusci Anne and Acquisition™, a full-body recording mannequin with a skill-reporting system.11 At 20 weeks after BLS training, participants were asked to perform continuous chest compressions on a mannequin for 3 minutes. For each resuscitation attempt, the rate and depth of compressions were recorded.

The participants’ retention of knowledge was evaluated immediately and 20 weeks after BLS training by 22-point questionnaire.4 Question 22 (chest compression rate) was adjusted according to the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) guidelines of 2005.10 Question 7 was altered according to the relevant ambulance call number in Japan.

The primary outcome measure was percentage chest compressions with adequate depth (38–51 mm). Secondary outcome measures were compression depth, compression rate, proportion of participants who could ensure an adequate mean compression depth (38–51 mm) and adequate mean compression rate (90–110/minute),11 and the score on the 22-point questionnaire. The adequate depth and rate of chest compressions were set according to a previous study11 and 2005 AHA guidelines.

Blinding

Clearly, it was not possible to blind the participants and instructors to their allocated groups. However, the computer screen of the skill-reporting system was not visible to the participants and no feedback from the screen was given.11 The questionnaires were scored by an investigator who was blinded to the status of the participants.

Statistical analysis

We did not perform a power calculation to determine the sample size to detect the differences between the two groups because of the limitations of our setting. Since the number of fourth-year medical students attending an OSCE within their regular medical training was 93, we were limited to recruitment of a maximum of that number. Therefore to compare the outcome measures between the groups we calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the difference between the two means instead of detecting a significant difference. We used the chi-square test to compare the proportion of participants who could ensure adequate compression rates or depths between the two groups.

Results

In total, 93 fourth-year students were recruited. The baseline characteristics of the participants were similar between the two groups (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial. The professional-led group consisted of more men. A total of 14 participants (four in the peer-led group and ten in the professional-led group) did not return for the 20-week follow-up after training. Moreover, 15 participants (ten in the peer-led group and five in the professional-led group) declined the evaluation of chest compressions. In total, of the 74 participants who underwent BLS training, 45 (23 in the peer-led group and 22 in the professional-led group) participated in the evaluation of chest compressions.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of student participants

| Peer-led group | Professional-led group | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 23.6 ± 1.5 | 24.0 ± 1.3 |

| Height (cm) | 164.8 ± 7.5 | 167.3 ± 7.5 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.4 ± 12.9 | 58.0 ± 9.0 |

Note: Values are mean ± standard deviation.

Table 2 summarizes the outcome measures. The primary outcome (percentage chest compressions with adequate depth) was similar between the two groups, with a 95% CI of the difference of the means −18.7% to 22.8%. One of the secondary outcome measures, proportion of participants who could ensure adequate compression rate, was 17/23 (73.9%) in the peer-led group but only 8/22 (36.4%) in the professional-led group (P = 0.011). The questionnaire scores were similar between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of outcome measures between peer-led group and professional-led group

| Chest compression | Peer-led group | Professional-led group | Difference of means (95% CI) or P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression depth (mm) | 43.5 ± 7.6 | 42.8 ± 9.5 | 0.75 (−4.5 to 6.0) |

| Percent compression with adequate depth (38–51 mm) (%) | 54.5 ± 31.9 | 52.5 ± 35.6 | 2.0 (−18.7 to 22.8) |

| Proportion of participants with adequate compression depth, n (%) | 16/23 (69.6) | 12/22 (54.5) | P = 0.299 |

| Compression rate (per minute) | 104.3 ± 9.1 | 109.6 ± 10.6 | −5.3 (−14.4 to 3.7) |

| Proportion of participants with adequate compression rate (90–110/minute), n (%) | 17/23 (73.9) | 8/22 (36.4) | P = 0.011 |

| Questionnaire scores | |||

| I mmediately after BLS training | 18.2 ± 1.4 | 18.0 ± 1.7 | 0.27 (−0.45 to 0.99) |

| At 20 weeks after BLS training | 17.2 ± 2.3 | 17.8 ± 2.0 | −0.57 (−1.72 to 0.57) |

Notes: Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise specified;

chi-square test.

Abbreviation: BLS, basic life support.

Discussion

This trial showed that peer-led training in BLS by medical students is feasible and as effective as health professional-led training. The primary outcome measure, percentge chest compressions with adequate depth, was similar between the two groups, although the broad 95% CI of the difference between the means of the measure was inconclusive. Other outcome measures showed that the peer-led group performed as well as or better than the professional-led group. The proportion of participants who could ensure adequate compression rate was significantly higher in the peer-led group than in the professional-led group. On the questionnaire score, the narrow 95% CIs of the difference in the means between the two groups both immediately and at 20 weeks after BLS training also suggest that training provided by the peer medical students was not inferior to that by the professionals.

Medical students have been reportedly successfully involved in teaching BLS in various settings.2,4,12–14 In these studies, however, the teaching skills of medical students were not compared with those of experts. Additionally, evaluation of the quality of educational training is often difficult. Significance of randomized controlled trials, which provide strong evidence, remains to be established in medical education. 5 Previous studies,6,7 however, adopted this design to compare peer-led with expert-led resuscitation. Perkins et al6 showed that undergraduate medical, dental, nursing, and physiotherapy students taught by their peers were more successful in an examination in BLS than those taught by clinical staff. In another example, a randomized controlled trial7 showed that advanced cardiac resuscitation can be safely and effectively taught to medical students by their peers. To judge the quality of educational interventions, these studies use evaluation data from students, eg, the exam pass rate, rather than outcomes. In the present study, we used parameters in chest compressions as feasible outcome measures for comparison, as well as questionnaire scores.

In Japan, individuals who are familiar with the traditional approach towards education, which stresses didactic lectures, book-learning, and memorization,8 are concerned about the quality of peer-led training by medical students. Contrarily, this study provides evidence supportive of adequate teaching skills of students even in the traditional setting of medical education. In Japan, about 30 medical student-run organizations teach BLS. More than 800 medical students annually participate in this activity.15

We acknowledge, however, that the study has certain limitations. First, owing to the limited number of medical students, we could not perform a power calculation to determine the sample size to detect differences between the two groups or to demonstrate noninferiority. Second, 29 people declined participation after randomization, which may have led to bias. Third, the instructors of the peer-led group were recruited from a student-led interest group in BLS. This may have caused an overestimation of the effect of the training.

Conclusion

Peer-led training in BLS by medical students is feasible and as effective as health professional-led training, although a much larger, randomized controlled trial is needed to provide stronger evidence. Our findings suggest that medical students are valuable resources to teach BLS skills.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating medical students and clinical staff at Ehime University School of Medicine.

This study was funded by research grant for students founded by Ehime University. The Life Support Workshop in Ehime financially contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. Trial registration UMIN-Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000001533.

References

- 1.Herlitz J, Svensson L, Holmberg S, Angquist KA, Young M. Efficacy of bystander CPR: intervention by lay people and by health care professionals. Resuscitation. 2005;66(3):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uray T, Lunzer A, Ochsenhofer A, et al. Feasibility of life-supporting first-aid (LSFA) training as a mandatory subject in primary schools. Resuscitation. 2003;59(2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breckwoldt J, Beetz D, Schnitzer L, Waskow C, Arntz HR, Weimann J. Medical students teaching basic life support to school children as a required element of medical education: a randomised controlled study comparing three different approaches to fifth year medical training in emergency medicine. Resuscitation. 2007;74(1):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toner P, Connolly M, Laverty L, McGrath P, Connolly D, McCluskey DR. Teaching basic life support to school children using medical students and teachers in a ‘peer-training’ model – results of the ‘ABC for life’ programme. Resuscitation. 2007;75(1):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glynn LG, MacFarlane A, Kelly M, Cantillon P, Murphy AW. Helping each other to learn – a process evaluation of peer assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins GD, Hulme J, Bion JF. Peer-led resuscitation training for healthcare students: a randomised controlled study. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):698–700. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes TC, Jiwaji Z, Lally K, et al. Advanced Cardiac Resuscitation Evaluation (ACRE): a randomised single-blind controlled trial of peer-led vs expert-led advanced resuscitation training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:3. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo A. The current state of medical education in Japan: a system under reform. Med Educ. 2007;41(3):302–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wik L, Brennan RT, Braslow A. A peer-training model for instruction of basic cardiac life support. Resuscitation. 1995;29(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)00835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association. American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl 24):IV1–IV203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones I, Whitfield R, Colquhoun M, Chamberlain D, Vetter N, Newcombe R. At what age can schoolchildren provide effective chest compressions? An observational study from the Heartstart UK schools training programme. BMJ. 2007;334(7605):1201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39167.459028.DE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robak O, Kulnig J, Sterz F, et al. CPR in medical schools: learning by teaching BLS to sudden cardiac death survivors–a promising strategy for medical students? BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins GD, Hulme J, Shore HR, Bion JF. Basic life support training for health care students. Resuscitation. 1999;41(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walters WA, Bailey H, Kaplan LJ. Can preclinical medical students be integrated into the continuing medical education process by instructing prehospital care providers? Am J Surg. 2000;179(3):229–233. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marukawa S. Report paper of the health labour sciences research grant Tokyo the ministry of health labour and welfare. 2009. A Research on dissemination of automated external defibrillator and basic life support to increase chance of survival: comprehensive research on prevention of cardiovascular diseases and other lifestyle [Japanese] [Google Scholar]