Abstract

Levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) delivered continuously via percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy (PEG-J) tube has been reported, mainly in small open-label studies, to significantly alleviate motor complications in Parkinson’s disease (PD). A prospective open-label, 54-week, international study of LCIG is ongoing in advanced PD patients experiencing motor fluctuations despite optimized pharmacologic therapy. Pre-planned interim analyses were conducted on all enrolled patients (n = 192) who had their PEG-J tube inserted at least 12 weeks before data cutoff (July 30, 2010). Outcomes include the 24-h patient diary of motor fluctuations, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I), Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), and safety evaluations. Patients (average PD duration 12.4 yrs) were taking at least one PD medication at baseline. The mean (±SD) exposure to LCIG was 256.7 (±126.0) days. Baseline mean “Off” time was 6.7 h/day. “Off” time was reduced by a mean of 3.9 (±3.2) h/day and “On” time without troublesome dyskinesia was increased by 4.6 (±3.5) h/day at Week 12 compared to baseline. For the 168 patients (87.5%) reporting any adverse event (AE), the most common were abdominal pain (30.7%), complication of device insertion (21.4%), and procedural pain (17.7%). Serious AEs occurred in 60 (31.3%) patients. Twenty-four (12.5%) patients discontinued, including 14 (7.3%) due to AEs. Four (2.1%) patients died (none deemed related to LCIG). Interim results from this advanced PD cohort demonstrate that LCIG produced meaningful clinical improvements. LCIG was generally well-tolerated; however, device and procedural complications, while generally of mild severity, were common.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel, Motor fluctuations, PEG-J procedure, Pump administration

1. Introduction

Dopamine replacement with levodopa was first shown to reduce clinical signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) in the 1960s [1], and since then has been the mainstay of PD treatment [2,3]. However, the majority of patients who respond to levodopa eventually experience a narrowing of the therapeutic window, resulting in motor complications, including “Off” time (when medication has worn off and parkinsonian symptoms re-emerge) and levodopa-induced dyskinesias [2]. These complications can be a major source of distress and disability for patients and are difficult to treat [4,5]. “Off” time is of particular interest, as this is arguably the biggest contributor to functional impairment in patients with advancing PD [6–9]. Hence, the ability to reduce “Off” time without an associated increase in dyskinesia is an important goal of therapy development.

The mechanisms behind levodopa-associated motor complications are not fully understood, but are hypothesized to be related to the inability of conventional levodopa regimens to provide physiologic, continuous dopaminergic stimulation [2,5,10]. Levodopa is rapidly metabolized and has a short plasma half-life of approximately 90 min (when administered with carbidopa), thus requiring frequent, repeated dosing and producing fluctuations in drug plasma levels [2,11]. It is absorbed mainly in the proximal small intestine, and gastric emptying plays an important role in determining the absorption of conventional oral levodopa formulations. Impaired gastric emptying is common in PD, and likely contributes to the unpredictable motor responses observed with orally-dosed levodopa [12,13]. Levodopa–carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) is a carboxymethylcellulose aqueous gel delivered directly to the proximal jejunum via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy (PEG-J) tube connected to a portable infusion pump [14,15]. Continuous infusion of LCIG bypasses gastric emptying, thereby avoiding this potential cause of suboptimal levodopa response [16].

Early studies used differing preparations of levodopa for intestinal infusion, but yielded consistent results. Stocchi and colleagues [17] reported that continuous nasoduodenal-tube administration of levodopa methyl ester for 6 months in 6 advanced PD patients significantly reduced trough plasma levels of levodopa, total “Off” time and “On” time with dyskinesias. Similarly, 24 patients with advanced PD who received daytime levodopa intestinal infusion showed a significant improvement of PD symptoms and quality of life (QOL) measures compared to standard oral therapy [18].

The LCIG (Duodopa®) formulation of levodopa is approved for clinical use in more than 30 countries and has been used in approximately 2800 patients world-wide. The French Duodopa Study Group recently reported retrospective safety and efficacy data from all patients in France who had received LCIG [19]. Of the 75 patients assessed for efficacy, motor fluctuations improved in 96.0% and dyskinesia improved in 94.7%. Only 1 patient reported worsening of motor symptoms leading to discontinuation. Adverse events (AEs) related to technical problems, gastrostomy procedure, and levodopa treatment were reported by 62.6%, 19.8%, and 2.2% of patients, respectively. Of the 91 patients assessed for safety, 18.7% (n = 17) discontinued treatment [19]. A recent meta-analysis focusing on LCIG infusion in advanced PD patients reported a consistent efficacy pattern in the reduction of levodopa-related motor complications, including improvement in motor scores and QOL scores [20]. While the AE profile of LCIG was similar to that of oral levodopa, technical problems with the infusion system occurred in up to 70% of patients [20]. However, most of these problems were mild to moderate in severity, of short duration, and led to only small numbers of discontinuations. These technical complications and AE profile remain to be substantiated by a controlled, long-term prospective study.

We present here the interim results of a large, open-label, international, safety trial of LCIG in patients with advanced PD and motor fluctuations despite optimized standard therapy. The study was primarily designed to collect long-term safety data to support the registration of LCIG in the United States, while also providing long-term efficacy data. The study represents the largest cohort of advanced PD patients treated with LCIG to date.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

A phase 3, open-label, 54-week trial of LCIG in patients with advanced PD and motor fluctuations despite optimized standard therapy is ongoing (Study start: January 2008; CT.gov identifier NCT00335153). There are 86 study sites in 16 countries world-wide, with planned enrollment of 320 patients. The study protocol was approved by each institution’s respective internal review board or ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to any procedure being performed. The interim analysis was primarily conducted to ensure that the operational aspects of the study were adequate and optimized for the ongoing pivotal trials of LCIG. The primary time point for the evaluation of efficacy is Week 12, to reflect the primary efficacy time point defined in the randomized, active-comparator pivotal trials.

2.2. Patients

The interim analysis presented here includes all patients who had their PEG-J tube inserted 12 weeks before the data cutoff date of July 30, 2010. Major inclusion criteria include: age ± 30 years; diagnosis of PD according to United Kingdom PD Society Brain Bank criteria; levodopa-responsive, with significant motor fluctuations despite optimized PD therapy, as judged by the investigator; recognizable “Off” and “On” states, with a minimum 3 h “Off” time per day at baseline, and the ability (by patient or caregiver) to competently maintain a standard PD diary. Major exclusion criteria include: unclear PD diagnosis, or suspicion of a Parkinson-plus syndrome or other neurodegenerative disorder; history of surgical treatment for PD; Mini-Mental State Examination score < 24; presence of sleep attacks and clinically significant impulsive behaviors during the 3 months prior to screening; current primary psychiatric diagnosis of acute psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder; or a history or presence of any condition that might interfere with absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of study drug or any contraindication to placement of intrajejunal PEG-J tube.

2.3. LCIG dosing

LCIG contains 20 mg/mL levodopa and 5 mg/mL carbidopa and is supplied in cassettes containing 100 mL of gel solution, a sufficient daily dose for most patients [15,21,22]. LCIG is administered with a portable infusion pump (CADD-Legacy® Duodopa, Smiths Medical, MN, USA). Individually-optimized dosing of LCIG was delivered over a 16-h period, administered as a morning bolus followed by continuous infusion, and if needed, intermittent extra doses (patient-initiated based on symptom experience). The volume of the morning bolus was individualized for each patient based initially on the total oral levodopa dose during the screening period. The total morning dose was usually 5–10 mL, corresponding to 100–200 mg levodopa, and did not exceed 20 mL (400 mg levodopa). Extra doses were adjusted individually during the titration period and remained fixed unless adjusted by the investigator. Extra doses were permitted at intervals of no less than 2 h. A maximum of 8 extra doses was possible during a 16-h treatment day. However, the use of 5 extra doses per any given 16-h period resulted in an adjustment of the following day’s continuous rate.

Initially, LCIG was administered via nasojejunal (NJ) tube (Bengmark Nutricia Ch10, Cook NJFT-10, or Stabilife Ch10 nasointestinal tube) for 2–14 days to assess the response to LCIG. If LCIG was tolerated and a clear treatment response was observed, patients underwent PEG-J tube placement for long-term administration. PEG (15 Fr FREKA) and J-tubes (9 Fr J-extension) were placed in a single procedure under local anesthesia using endoscopic and/or fluoroscopic guidance. Patients were hospitalized for NJ-tube insertion (with the option of returning home after initial LCIG dose optimization) and for PEG-J tube placement with dose optimization based on hourly monitoring of the patient’s motor state.

2.4. Concomitant medication

Except for LCIG, all other PD drugs (including dopamine-agonists, apomorphine, and catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors) were stopped prior to the NJ treatment period; these medications could be re-initiated after 28 days at the investigator’s discretion. Oral levodopa—carbidopa medication (immediate-release tablets) could be used at night, when the LCIG pump was turned off for 8 h, but was not allowed within 2 h of the morning bolus.

2.5. Efficacy

Baseline motor symptoms were assessed using a 24-h diary (Hauser diary [8]) for 3 consecutive days prior to NJ-tube insertion. Patients recorded motor symptom status every 30 min throughout the waking day. Due to the variation in waking hours among patients and of individual patients across days in this advanced PD cohort, PD symptom diary data were normalized to a 16-h waking time. The normalization was calculated as (observed hours per day) × (16/waking hours). For example, a patient with 12 h of awake symptom diary data had their “Off” time adjusted by a factor of 1.33 (16 h/12 h). Alternatively, a patient with 20 h of awake symptom diary data had their “Off” time adjusted by a factor of 0.8 (16 h/20 h). All non-waking hours were denoted as “sleep” time. For the 3 days before each scheduled visit, patients were instructed to record motor symptoms using the diary. All variables describing diary-based motor symptoms represent the average of three days’ results and were normalized as above. At the time of NJ-tube placement, investigators rated patients on the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) – Severity (scored 1 [normal] to 7 [most extremely ill]).

“Off” time is the study’s primary efficacy measure. Secondary efficacy measures include: “On” time without troublesome dyskinesia, which is a sum of two diary entries (“On” time with non-troublesome dyskinesia and “On” time without dyskinesia); “On” time with troublesome dyskinesia; the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores – Total (sum of Parts I, II, and III), Part I (mentation, behavior, and mood), Part II (activities of daily living), Part III (motor examination; measured in the “On” state and 1–4 h after the LGIC morning bolus); CGI-Improvement (scored 1 [very much improved] to 7 [very much worse]) subscales; and, health outcome assessments, including the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 summary index (PDQ-39; scored 0–100, higher is worse), the EQ-5D summary index score (EuroQol-5 Dimension patient questionnaire, scored 0–1, higher is better), and the EQ-VAS score (EuroQol Visual Analog Scale score; patient-rated health, scored 0–100, higher is better). Efficacy assessments were collected at scheduled visits of Post-PEG Week 4, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 54. UPDRS assessments were conducted within 1–4 h of the morning oral levodopa dose at baseline, and within 1–4 h of the morning bolus dose of LCIG at subsequent clinic visits.

2.6. Safety

AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) and were tabulated by System Organ Class (SOC) and MedDRA preferred term (PT). Study investigators recorded the start and stop date of each event, or designated it as “ongoing” at the end of the study. Investigators rated each AE as mild, moderate, or severe, and judged the potential relationship with study treatment. Serious AEs (SAEs) were defined as any untoward medical occurrences that resulted in persistent or significant disability; required hospitalization or prolonged existing hospitalization; or were life-threatening. Treatment-emergent AEs were defined as those that began or worsened on or after the day of NJ-tube insertion and within 1 or 30 days of the last LCIG treatment, for non-serious AEs or SAEs, respectively. “AEs of special interest” related to PEG-J tube insertion (including pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, intestinal perforation, and postoperative ileus) were pre-specified in the protocol based on known complications of the procedure.

2.7. Statistical analyses

For all analyses, “baseline” is defined as the last available data collected prior to NJ-tube insertion. For all efficacy variables except the CGI-I, change from baseline to each post-PEG assessment was summarized for the observed cases. The within-group magnitude of change was tested using a one-sample t-test. Summary statistics for CGI-I at each time point are presented. For safety data, the incidence of AEs and SAEs was summarized.

3. Results

One-hundred ninety-two patients met criteria for inclusion in the interim analysis (59.4% male; mean [SD] age of 64.1 [9.1] yrs; mean [SD] PD duration, 12.4 [5.8] yrs; 72.4% were taking at least 2 PD medications). At baseline, patients had a mean (SD) “Off” time of 6.7 (2.4) h/day and mean (SD) CGI – Severity rating of 4.9 (0.8) (5 = markedly ill). Baseline characteristics (at the time of NJ-tube insertion) are summarized in Table 1. At the interim cutoff, 69 patients (35.9%) had completed 54 weeks of treatment, 99 (51.6%) were ongoing, and 24 (12.5%) had withdrawn from the study (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Study population baseline characteristics.

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 192 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.1 (9.1) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 114 (59.4) |

| Race, n (%) | White | 183 (95.3) |

| Asian | 8 (4.2) | |

| Black | 1 (0.5) | |

| PD duration (years), mean (SD) | 12.4 (5.8) | |

| Taking levodopa or derivatives, n (%) | Alone | 53 (27.6) |

| With 1 other PD drug | 62 (32.3) | |

| Dopamine-agonists | 33 (17.2) | |

| COMT-inhibitors | 18 (9.4) | |

| Amantadine derivatives | 8 (4.2) | |

| MAO-B inhibitors | 2 (1.0) | |

| With 2 other PD drugs | 46 (24.0) | |

| Dopamine-agonists | 38 (19.8) | |

| COMT-inhibitors | 24 (12.5) | |

| Amantadine derivatives | 21 (10.9) | |

| MAO-B inhibitors | 5 (2.6) | |

| With≥ 3 other PD drugs | 31 (16.1) | |

| Dopamine-agonists | 29 (15.1) | |

| COMT-inhibitors | 19 (9.9) | |

| Amantadine derivatives | 26 (13.5) | |

| MAO-B inhibitors | 13 (6.8) | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam score, mean (SD) | 28.5 (1.7) | |

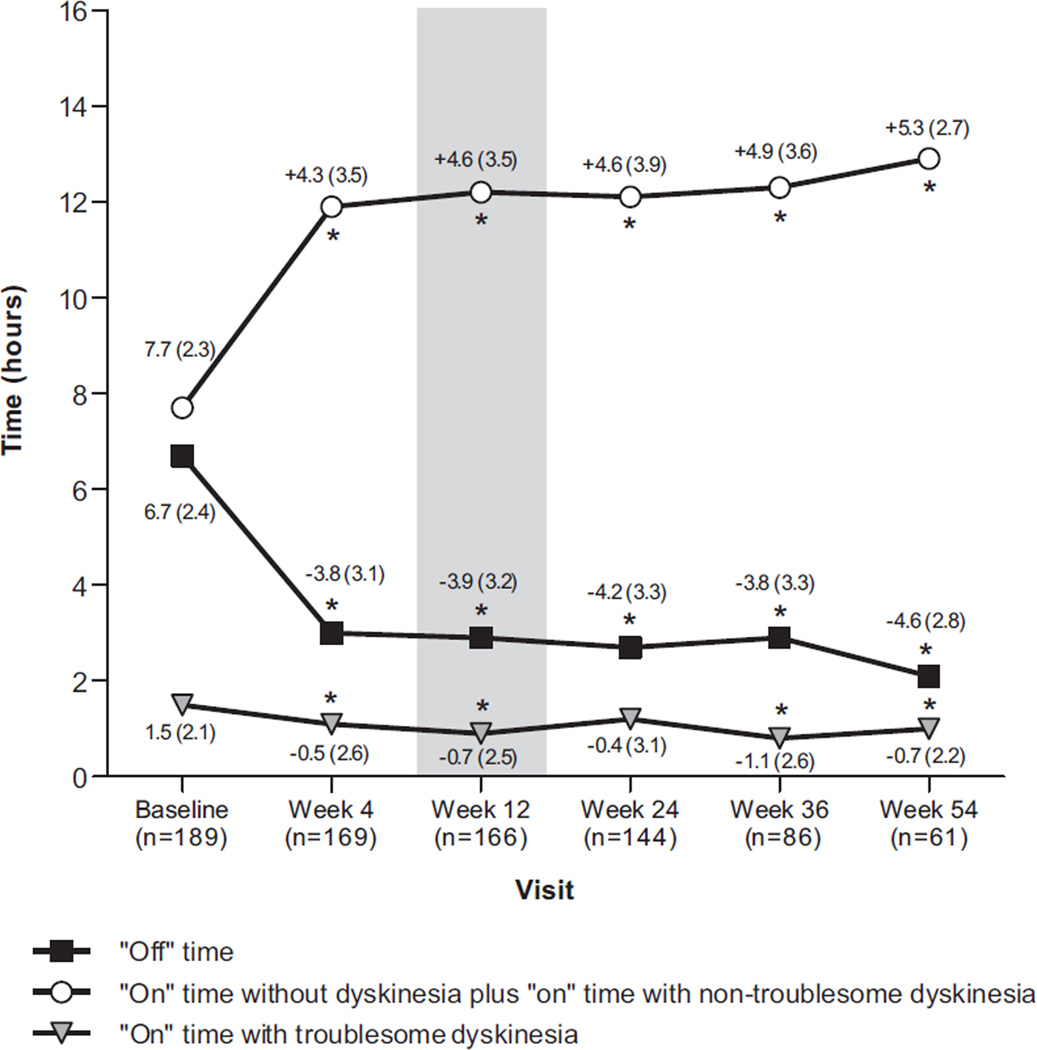

Mean “Off” time was significantly reduced at all time points (P < 0.001 versus baseline). At Week 12, the mean (SD) reduction in “Off” time was 3.9 (3.2) h/day (Fig. 1). This benefit was sustained in 61 patients who had data for Week 54, showing a mean (SD) reduction in “Off” time of 4.6 (2.8) h/day. Similarly, “On” time without troublesome dyskinesia was improved at all time points (P < 0.001 versus baseline). This measure increased by a mean (SD) of 4.6 (3.5) h/day at Week 12 and 5.3 (2.7) h/day among patients who reached Week 54. “On” time with troublesome dyskinesias significantly improved from 1.5 (2.1) h/day at baseline to 0.9 (1.8) h/day at Week 12 (P < 0.05) and 1.0 (1.5) h/day at Week 54 (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Mean daily “Off” time, “On” time with troublesome dyskinesia, and “On” time without dyskinesia plus “On” time with non-troublesome dyskinesia (diary-based, observed cases). Values are averaged for the 3 days prior to each clinic visit and normalized to a 16-h waking day. For each measure, numbers represent the mean (SD) for baseline or the change from baseline at subsequent visits. *P < 0.05 versus baseline by one-sample t-test.

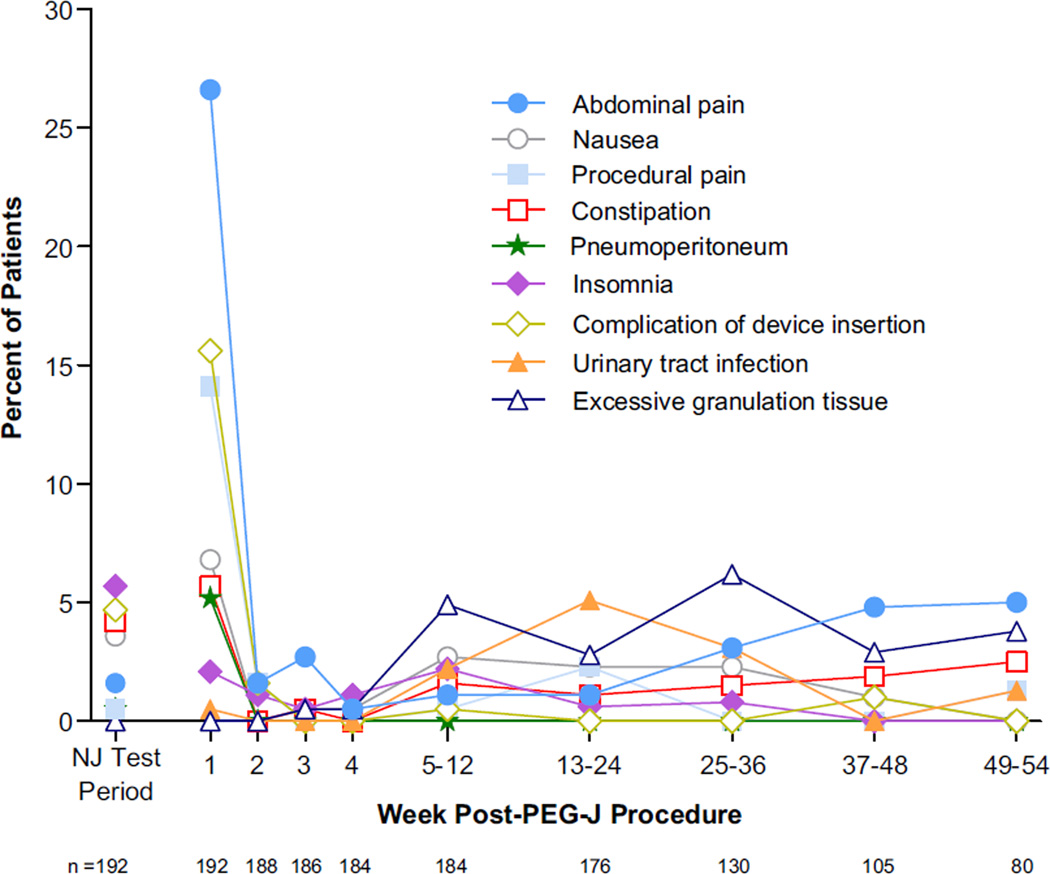

A total of 168 patients (87.5%) reported at least one AE. Most AEs were mild to moderate. SAEs were reported in 60 patients (31.3%). AEs reported in ≥5% of patients are listed in Table 2. Abdominal pain was the most common, reported by 59 patients (30.7%). Seventeen (8.8%) of these were judged to be directly related to the PEG-J procedure. “AEs of special interest” related to PEG-J tube placement were reported in 20 patients (10.4%). Seven patients had peritonitis; all occurred within 2 weeks of PEG-J tube placement. There were 5 cases of polyneuropathy (PN), and 4 were considered serious. Of these, 3 patients had acute to sub-acute onset of PN symptoms, while one had a history of sensory neuropathy. The latter patient’s symptoms resolved after treatment with hydroxycobalamin, while 2 others’ symptoms were ongoing at the interim data cutoff. One patient with PN discontinued treatment. The incidence of AEs reported by ≥5% of patients as a function of time is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent and serious adverse events (AEs).

| System organ class | Preferred term | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment-emergent AEs reported in ≥5% of patients | ||

| All | Total | 168 (87.5) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications, n = 104 (54.2%) | Complication of device insertion | 41 (21.4) |

| Procedural pain | 34 (17.7) | |

| Fall | 21 (10.9) | |

| Incision-site erythema | 18 (9.4) | |

| Procedural-site reaction | 17 (8.9) | |

| Postprocedural discharge | 16 (8.3) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders, n = 96 (50.0%) | Abdominal pain | 59 (30.7) |

| Constipation | 26 (13.5) | |

| Nausea | 26 (13.5) | |

| Diarrhea | 16 (8.3) | |

| Dyspepsia | 15 (7.8) | |

| Vomiting | 14 (7.3) | |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 11 (5.7) | |

| Nervous system disorders, n = 74 (38.5%) | Dyskinesia | 21 (10.9) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 18 (9.4) | |

| Headache | 17 (8.9) | |

| Psychiatric disorders, n = 73 (38.0%) | Insomnia | 21 (10.9) |

| Anxiety | 20 (10.4) | |

| Depression | 14 (7.3) | |

| Sleep attacks | 11 (5.7) | |

| Infections and infestations, n = 64 (33.3%) | Postoperative wound infection | 20 (10.4) |

| Urinary tract infection | 15 (7.8) | |

| Musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorders, n = 50 (26.0%) | Back pain | 13 (6.8) |

| Pain in extremity | 11 (5.7) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders, n = 43 (22.4%) | Excessive granulation tissue | 26 (13.5) |

| Respiratory/thoracic/mediastinal disorders, n = 40 (20.8%) | Oropharyngeal pain | 16 (8.3) |

| Investigations, n = 36 (18.8%) | Weight decreased | 16 (8.3) |

| Vascular disorders, n = 29 (15.1%) | Orthostatic hypotension | 16 (8.3) |

| Serious AEs reported in ≥2 patients | ||

| All | Total | 60 (31.3) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications, n = 25 (13.0%) | Complication of device insertion | 13 (6.8) |

| Device dislocation | 3 (1.6) | |

| Hip fracture | 3 (1.6) | |

| Medical-device complication | 2 (1.0) | |

| Radius fracture | 2 (1.0) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders, n = 24 (12.5%) | Abdominal pain | 9 (4.7) |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 7 (3.6) | |

| Peritonitis | 6 (3.1) | |

| Small-intestinal obstruction | 2 (1.0) | |

| Nervous system disorders, n = 12 (6.3%) | Polyneuropathy | 4 (2.1) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 3 (1.6) | |

| Syncope | 3 (1.6) | |

| Psychiatric disorders, n = 8 (4.2%) | Depression | 3 (1.6) |

| Anxiety | 2 (1.0) | |

| Infections and infestations, n = 8 (4.2%) | Pneumonia | 3 (1.6) |

| Pyelonephritis | 2 (1.0) | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, n = 4 (2.1%) | Back pain | 2 (1.0) |

Fig. 2.

Incidence of treatment-emergent AEs reported by ≥5% of patients during any time interval. Because many patients in this cohort had not completed the study by the data cutoff date, rates of AEs after 12 weeks may change. Time points after Week 4 summarize data for AEs initiating over multiple weeks. Abdominal pain = abdominal pain + abdominal pain upper + abdominal pain lower. Two patients had abdominal pain events that were counted in 2 of the 3 categories. Complication of device insertion includes AEs already reported that were related to device insertion, as judged by the investigator. Urinary tract infection = urinary tract infection + urinary tract infection fungal. Insomnia = insomnia + middle insomnia.

AEs led to discontinuation of 14 patients (7.3%). Reasons for discontinuation included (patients could list more than one): dyskinesias and worsening of motor symptoms (n = 4); gastrointestinal complications (n = 3, including abdominal pain, n = 2; intestinal ulcer, n = 1; peritonitis, n = 1; and vomiting, n = 1); device complications (n = 2); peritoneal abscesses (n = 1); PN (n = 1); hip fracture (n = 1). Of the 4 deaths, 2 (suicide; septic shock following acute renal failure) were judged to be unrelated to study medication or PEG-J, and the other 2 (cachexia after hip fracture; sudden death after surgery for fractured humerus) were judged unlikely to be related to study medication.

Secondary efficacy measures supported findings on the primary efficacy measure. Substantial and sustained improvement (P < 0.001 versus baseline) was observed in the UPDRS total and subscale scores, the PDQ-39 summary index, EQ-5D summary index, and EQ-VAS. During LCIG administration, mean CGI-Improvement ratings approached 2, or “much improved” (See Electronic Supplementary materials).

4. Discussion

This is the largest prospective, open-label study of LCIG to date. These interim results indicate that LCIG produces clinically meaningful improvements of motor function in advanced PD patients with motor fluctuations despite optimized oral medical treatment. LCIG is generally well-tolerated even in this patient population. Total “Off” time improved substantially and consistently over 54 weeks without any concurrent increase in “On” time with troublesome dyskinesias. Additionally, the average improvement from baseline in “Off” time of 3.9 h/day with LCIG is substantially greater than that reported in placebo-controlled or open-label studies of oral agents such as rasagiline and entacapone when used as an adjunctive therapy to levodopa in similar patient populations [23–25]. Indeed, the magnitude of improvement in “Off” time is closer to that reported in studies of deep brain stimulation [26,27]. The clinical significance of the improvements produced by LCIG therapy is further supported by the secondary endpoints, including QOL measures.

While the present results support the effects of LCIG reported in earlier smaller trials, there are limitations to the interpretation of these data. As interim results, they are subject to change based upon analysis of the final, complete dataset. In addition, these data are from an open-label study and a contribution of placebo effect cannot be excluded. These findings will need to be confirmed in randomized, double-blind, double-dummy studies (NCT00357994, NCT00660387).

SAEs were reported in 60 patients (31.3%), but AEs led to discontinuation of therapy in only 14 (7.3%) of the 192 patients included in this cohort. However, as only 69 patients had completed 54 weeks of treatment before the cutoff date, the total number of discontinuations and those due to AEs will likely be higher at study completion. Still, over an average of more than 8 months, the AE profile resembles the safety pattern associated with PEG-tube-related complications in general [28–30]. Moreover, the peak incidence of AEs corresponded temporally with the PEG-J procedure, including the cases of peritonitis and pneumoperitoneum (an expected consequence of PEG-J procedure). This is an important consideration, given that this is a time when patients are likely to be hospitalized, or under close medical supervision. Nonetheless, the overall prevalence of GI side effects, device- and procedure-related events, though often mild to moderate, was high, requiring technical expertise in PEG-J placement, proper care and maintenance, and good communication between the gastroenterologist and neurological team. Serious device-related complications following the PEG-J procedure, while rare, occasionally required re-intervention. Our overall experience across clinical studies of LCIG has shown that at 1 year, 91.6% of PEG tubes did not need to be replaced, and 63.7% of J-tubes did not need to be replaced (Abbott data on file).

Nervous system AEs were relatively infrequent; there was a notable paucity of symptoms associated with dopaminergic toxicity, such as hallucinosis or behavioral dyscontrol. There were, however, 5 cases of PN, 4 of which were considered serious, and 1 resulting in study withdrawal. PN has been increasingly observed in PD [31,32], and most cases are of the mild to moderate axonal variety. The epidemiological data are still incomplete, and the incidence and prevalence of this problem in PD, as well as the underlying etiologies, remain uncertain. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including effects of long-term exposure to levodopa/carbidopa [32], and related metabolites [33]. It is possible that levodopa induces changes in homocysteine and B6. In addition, there may be other factors such as vitamin B12 deficiency or hyperhomocysteinemia contributing to the onset or worsening of PN in PD patients [31–34]. The relationship between PN and PD treatments requires further observation and study. Results from the complete open-label study dataset and pivotal trials may provide insight to the prevalence of PN in association with LCIG.

The robust improvement in “Off” time provides further evidence that LCIG may be an important treatment modality for advanced PD. Here, LCIG was used primarily as a monotherapy, which may have additional benefits of increasing compliance and reducing drug-related AEs. It is clear, however, that continued vigilance is required regarding the occurrence of gastrointestinal and device-and/or procedure-related events. As more long-term data become available, it will be important to determine whether these AEs remain manageable and how they impact the patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the large numbers of study coordinators, titration nurses, and ancillary personnel that continue to make this trial possible. Site investigators are listed in Site Investigator Appendix in Supplementary materials. This study was supported by Abbott. Abbott was involved in the study design, the conduct of the trial, analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing and approval of this report. Weining Z. Robieson, of Abbott, provided support for statistical analyses, and Nathan R. Rustay, of Abbott, provided medical writing support.

Funding source

Abbott.

Footnotes

Full financial disclosures of all authors for the past year

Dr. Fernandez has received research support from Abbott, Acadia, Biotie Therapeutics, EMD-Serono, Huntington Study Group, Ipsen, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Movement Disorders Society, National Parkinson Foundation, NIH/NINDS, Novartis, Parkinson Study Group, and Teva, but has no owner interest in any pharmaceutical company. He has received honoraria from Cleveland Clinic CME, Northwestern University CME, Ipsen, Merz Pharmaceuticals, and US World Meds.

Dr. Vanagunas is a paid consultant for CVS Caremark’s Pharmacy & Therapeutics committee and Abbott, and has been a scientific advisory board member for Abbott.

Prof. Odin has been a study investigator in Abbott-sponsored studies, and has received compensation from Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Britannia, Cephalon, GSK, Ipsen, Lundbeck, Nordic Infucare and UCB for serving as a consultant and/or lecturer. He has received honoraria from Movement Disorder Society.

Dr. Espay is supported by the K23 Research Scholars mentored career development awards (NIMH, 1K23MH092735). He has received grant support from CleveMed/Great Lakes Neurotechnologies, Davis Phinney Foundation, and Michael J Fox Foundation; personal compensation as a consultant/scientific advisory board for Solvay, Abbott, Chelsea Therapeutics, TEVA, Eli Lilly, Impax, and Solstice Neurosciences; and honoraria from Novartis, the American Academy of Neurology, and the Movement Disorders Society.

Dr. Hauser has received honoraria or payments for consulting, advisory services, speaking services, research, and/or royalties over the past 12 months from: Abbott Laboratories, Allergan, Inc., AstraZeneca, Ceregene, Inc., Chelsea Therapeutics, Inc., GE Healthcare, Impax Laboratories, Inc., Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., Lundbeck, Merck/MSD, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Straken Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., Targacept, Inc., Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries, Ltd., Teva Neuroscience, Inc., Upsher-Smith Laboratories, UCB, Inc., UCB Pharma SA, Xenoport, Inc. In addition, Dr. Hauser has consulted in litigation with lawyers representing various current and former manufacturers of welding consumables.

Dr. Standaert is a member of the faculty of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and is supported by endowment and University funds. Dr. Standaert is an investigator in studies funded by Abbott Laboratories, the American Parkinson Disease Association, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Allon Therapeutics, the American Sleep Medicine Foundation, Addex Pharmaceuticals, the RJG Foundation, and NIH grants 5F30NS065661, 1F31NS076017, 5K08NS060948, 5R01MH082304, 5K08NS054811, 5K01NS069614, 1R01NS064934, and 5P50-NS037400. He has a clinical practice and is compensated for these activities through the University of Alabama Health Services Foundation. In addition, in the last two years he has served as a consultant for or received honoraria from Teva Neurosciences, Serina Therapeutics, Solvay (now Abbott), the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research, Partners Healthcare, the University of Michigan, Balch and Bingham LLC, the University of Arizona, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, North Shore Hospital, the Thomas Hartman Foundation, the Bachmann-Strauss Foundation, Nupathe Inc., Bradley Arrant Boult Cummings, and he has received royalties for publications from McGraw Hill, Inc.

Krai Chatamra, Janet Benesh, Yili Pritchett, Steven Hass, and Robert Lenz are employees of Abbott Laboratories and hold Abbott stock and/or stock options.

Financial disclosure/conflict of interest concerning the research related to the manuscript

Dr. Fernandez has served as a study investigator and a consultant for Abbott. A contract has been made between Abbott and Cleveland Clinic Foundation for any compensation received by Dr. Fernandez as a consultant; he has not received any personal compensation.

Dr. Vanagunas is an investigator for Abbott-sponsored studies, and is a paid consultant and scientific advisory board member for Abbott.

Prof. Odin has been a study investigator in Abbott-sponsored studies, and has received compensation from Abbott for serving as a consultant and lecturer.

Dr. Espay has been an investigator for Abbott-sponsored studies, and has received personal compensation from Solvay Pharmaceuticals (now Abbott) and Abbott for serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member.

Dr. Hauser has been an investigator for Abbott-sponsored studies, and has received personal compensation from Solvay Pharmaceuticals (now Abbott) for serving as a consultant and scientific advisory board member.

Dr. Standaert is an investigator in Abbott-sponsored studies, and has served as a consultant for or received honoraria from Solvay Pharmaceuticals (now Abbott).

Krai Chatamra, Janet Benesh, Yili Pritchett, Steven Hass, and Robert Lenz are employees of Abbott and receive compensation including salary, stock and/or stock options from Abbott.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.11.020.

References

- 1.Yahr MD, Duvoisin RC, Schear MJ, Barrett RE, Hoehn MM. Treatment of parkinsonism with levodopa. Arch Neurol. 1969;21:343–354. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480160015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauser RA. Levodopa: past, present, and future. Eur Neurol. 2009;62:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000215875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olanow CW, Agid Y, Mizuno Y, Albanese A, Bonuccelli U, Damier P, et al. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: current controversies. Mov Disord. 2004;19:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/mds.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenner P. Avoidance of dyskinesia: preclinical evidence for continuous dopaminergic stimulation. Neurology. 2004;62:S47–S55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1_suppl_1.s47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olanow CW, Obeso JA, Stocchi F. Continuous dopamine-receptor treatment of Parkinson’s disease: scientific rationale and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:677–687. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70521-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pechevis M, Clarke CE, Vieregge P, Khoshnood B, Deschaseaux-Voinet C, Berdeaux G, et al. Effects of dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease on quality of life and health-related costs: a prospective European study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:956–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Politis M, Wu K, Molloy S, P GB, Chaudhuri KR, Piccini P. Parkinson’s disease symptoms: the patient’s perspective. Mov Disord. 25:1646–1651. doi: 10.1002/mds.23135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauser RA, Friedlander J, Zesiewicz TA, Adler CH, Seeberger LC, O’Brien CF, et al. A home diary to assess functional status in patients with Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2000;23:75–81. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapuis S, Ouchchane L, Metz O, Gerbaud L, Durif F. Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson’s disease on the quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005;20:224–230. doi: 10.1002/mds.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stocchi F. The hypothesis of the genesis of motor complications and continuous dopaminergic stimulation in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chase TN. The significance of continuous dopaminergic stimulation in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Drugs. 1998;55:1–9. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurlan R, Rothfield KP, Woodward WR, Nutt JG, Miller C, Lichter D, et al. Erratic gastric emptying of levodopa may cause “random” fluctuations of parkinsonian mobility. Neurology. 1988;38:419–421. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nutt JG, Woodward WR, Hammerstad JP, Carter JH, Anderson JL. The “on-off” phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease. Relation to levodopa absorption and transport. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:483–488. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198402233100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonini A, Tolosa E. Apomorphine and levodopa infusion therapies for advanced Parkinson’s disease: selection criteria and patient management. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:859–867. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundqvist C. Continuous levodopa for advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:335–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonini A, Odin P. Pros and cons of apomorphine and L-dopa continuous infusion in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:S97–S100. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stocchi F, Vacca L, Ruggieri S, Olanow CW. Intermittent vs continuous levodopa administration in patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:905–910. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyholm D, Nilsson Remahl AI, Dizdar N, Constantinescu R, Holmberg B, Jansson R, et al. Duodenal levodopa infusion monotherapy vs oral polypharmacy in advanced Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64:216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149637.70961.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devos D. Patient profile, indications, efficacy and safety of duodenal levodopa infusion in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:993–1000. doi: 10.1002/mds.22450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez HH, Odin P. Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel for treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:907–919. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.560146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyholm D. Enteral levodopa/carbidopa gel infusion for the treatment of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:1403–1411. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.10.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyholm D, Askmark H, Gomes-Trolin C, Knutson T, Lennernas H, Nystrom C, et al. Optimizing levodopa pharmacokinetics: intestinal infusion versus oral sustained-release tablets. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:156–163. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200305000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkinson Study Group. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of rasagiline in levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson disease and motor fluctuations: the PRESTO study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:241–248. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rascol O, Brooks DJ, Melamed E, Oertel W, Poewe W, Stocchi F, et al. Rasagiline as an adjunct to levodopa in patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor fluctuations (LARGO, Lasting effect in Adjunct therapy with Rasagiline Given once daily, study): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2005;365:947–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinne UK, Larsen JP, Siden A, Worm-Petersen J. Entacapone enhances the response to levodopa in parkinsonian patients with motor fluctuations. Nomecomt Study Group. Neurology. 1998;51:1309–1314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, Volkmann J, Schafer H, Botzel K, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:896–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, Hur K, Harris C, Marks WJ, Jr, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301:63–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang JC. Minimizing endoscopic complications in enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClave SA, Chang WK. Complications of enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:739–751. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrag A, Quinn N. Dyskinesias and motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. A community-based study. Brain. 2000;123:2297–2305. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toth C, Breithaupt K, Ge S, Duan Y, Terris JM, Thiessen A, et al. Levodopa, methylmalonic acid, and neuropathy in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:28–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.22021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toth C, Brown MS, Furtado S, Suchowersky O, Zochodne D. Neuropathy as a potential complication of levodopa use in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1850–1859. doi: 10.1002/mds.22137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller T. Role of homocysteine in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:957–967. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller T, Kuhn W. Homocysteine levels after acute levodopa intake in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1339–1343. doi: 10.1002/mds.22607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]