Abstract

Mice of the 129/J (129) and C57BL/6ByJ (B6) strains and their reciprocal F1 and F2 hybrids were offered solutions of ethanol, sucrose, citric acid, quinine hydrochloride, and NaCI in two-bottle choice tests. Consistent with earlier work, the B6 mice drank more ethanol, sucrose, citric acid, and quinine hydrochloride solution and less NaCI solution than did 129 mice. Analyses of each generation’s means and distributions showed that intakes of ethanol, quinine, sucrose, and NaCI were influenced by a few genes. The mode of inheritance was additive in the case of ethanol and quinine, for sucrose the genotype of the 129 strain was recessive, and for NaCI it was dominant. Citric acid intake appeared to be influenced by many genes with small effects, with the 129 genotype dominant. Correlations of sucrose consumption with ethanol and citric acid consumption were found among mice of the F2 generation, and the genetically determined component of these correlations was stronger than the component related to environmental factors. The genetically determined correlation between sucrose and ethanol intakes is consistent with the hypothesis that the higher ethanol intake by B6 mice depends, in part, on higher hedonic attractiveness of its sweet taste component.

Keywords: Mouse, genetics, ethanol consumption, sweet, salty, bitter, sour

INTRODUCTION

Consistent with the multiple mechanisms involved in its regulation, the inheritance of ethanol-related behavior is multigenic (McClearn and Rodgers, 1961; Pickett and Collins, 1975; Phillips et al., 1994; Ball and Murray, 1994; Rodriguez et al., 1995). One factor that affects the proclivity to drink ethanol is the perception of its flavor (Nachman et al., 1971). Ethanol flavor has sweet and bitter components (Kiefer and Lawrence, 1988), and previous studies on humans and rodents have shown correlations between ethanol intake and sweet or bitter taste responses (Pelchat and Danowski, 1992; Belknap et al., 1993; Overstreet et al., 1993; Stewart et al., 1994). Indeed, it has been suggested that a high ethanol intake may depend on a reduced sensitivity to its bitterness or an enhanced sensitivity to its sweetness (Pelchat and Danowski, 1992; Bachrnanov et al., 1996). Several loci have been postulated to affect behavioral responses to bitter and sweet compounds (Lush, 1991; Ninomiya and Funakoshi, 1993; Whitney and Harder, 1994) but there is no strong evidence for a common genetic mechanism underlying ethanol intake and bitter or sweet taste sensitivity or, for that matter, sensitivity to any taste.

Mice of the C57BL/6ByJ (B6) and 129/J (129) strains can serve as a valuable model for studying the relationship between ethanol intake and taste. Various C57BL/6 substrains prefer ethanol solutions, whereas the 129 strain is among the strains avoiding ethanol; C57BL/6 and 129 strains are at the extremes of the mouse strains distribution for salty and sweet compound preference, and they differ also in consumption of bitter and sour solutions (Lush, 1991; Beauchamp and Fisher, 1993; Belknap et al., 1993; Capeless and Whitney, 1995; Bachmanov et al., 1996). This difference between the B6 and the 129 mice raises the possibility that ethanol and taste preferences in these strains may be influenced by pleiotropic or linked genes, but it is also possible that the strain differences could be due to several independent genes fortuitously fixed during inbreeding. To discriminate between these possibilities, in the present work we examined the genetic correlations of ethanol intake with intake of taste solutions representing the four main taste qualities using a segregating cross. We also characterized the mode of inheritance of consumption of ethanol and the taste solutions, which included estimation of the probable number of genes determining strain differences, allelic interactions, and the effects of reciprocal crossings. For this purpose, mice of the B6 and 129 strains and their hybrids of the first (F1) and the second (F2) generations were bred and tested for intake of ethanol, sucrose, citric acid, quinine, and NaCI.

METHODS

Subjects and Breeding of F1 and F2 Generations

Adult male and female 129/J and C57BL/6ByJ mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were used for breeding. The F1 was generated by reciprocal crosses using both strains and genders (female 129 × male B6; male 129 × female B6). Two types of F2 hybrids were produced, 129 × B6 F2 [(129 × B6 F1 females) × (129 × B6 F1 males)] and B6 × 129 F2 [(B6 × 129 F1 females) × (B6 × 129 F1 males)]. To reduce variation due to age or conditions of breeding and testing successive generations, mice from the parental strains and F1 were bred, raised, and tested simultaneously with the F2. Pups were weaned at 21–30 days of age and reared in same-sex groups of four to six. The numbers of animals and their average body weights before and after testing are shown in Table 1. We intentionally produced and phenotyped larger numbers of F2 males than F2 females in order to increase the power of the analyses of distributions and correlations (these analyses were conducted only in males). All mice were housed at 23°C on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle and had free access to water and Teklad Rodent Diet 8604.

Table I.

Number of Mice and Their Body Weights (mean ± SE)

| Body weight (g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Gender | Cross type |

n | Before tests | After tests |

| 129 | Males | 129×129 | 13 | 23.1 ± 0.7 | 23.0 ± 0.5 |

| Females | 129×129 | 20 | 17.3 ± 0.4 | 18.6 ± 0.4 | |

| B6 | Males | B6×B6 | 14 | 24.4 ± 0.7 | 26.6 ± 0.4 |

| Females | B6×B6 | 19 | 19.3 ± 0.3 | 21.8 ± 0.4 | |

| F1 | Males | 129×B6 | 26 | 26.6 ± 0.4 | 28.8 ± 0.5 |

| B6×129 | 16 | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 26.8 ± 0.4 | ||

| Females | 129×B6 | 27 | 22.2 ± 0.4 | 24.3 ± 0.3 | |

| B6×129 | 30 | 20.7 ± 0.3 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | ||

| F2 | Males | 129×B6 | 80 | 25.4 ± 0.3 | 26.3 ± 0.3 |

| B6×129 | 91 | 25.2 ± 0.3 | 25.9 ± 0.3 | ||

| Females | 129×B6 | 15 | 20.4 ± 0.5 | 21.9 ± 0.5 | |

| B6×129 | 15 | 19.6 ± 0.5 | 21.1 ± 0.6 | ||

Measurement of Taste Solution Intake

Taste solution intake was measured in two-bottle tests in individually caged adult mice (~60 days). Construction of the drinking tubes and other experimental details have been previously described (Bachmanov et al., 1996). Mice were presented with two drinking tubes positioned 15 mm apart, and to the right of the feeder. For the first 2 days, both tubes contained deionized water. Thereafter, one tube contained deionized water and another tube contained a taste solution (prepared in deionized water). The solutions were presented in the following order: 300 mM NaCl, 75 mM NaCl, 4% (w/v; 117 mM) sucrose, 0.1 mM citric acid (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO), 10% (v/v; 1700 mM) ethanol (Pharmco, Bayonne, NJ), 0.03 mM quinine hydrochloride (quinine HCl; Sigma). Each solution was presented for 4 days. The positions of the tubes were switched every 24 h of each 96-h test in order to avoid positional preferences. Between the test series, mice were offered water to drink for 2 days to offset any carryover effects, except for between 300 and 75 mM NaCl solutions. These solutions were tested without an intervening water-only period because we had previously found that the difference between 129 and B6 mice in intake of 75 mM NaCl was greater after they had access to more concentrated NaCl solutions (Beauchamp and Fisher, 1993; Bachmanov et al., 1994). Body weights were measured before and after each test series.

Data Analysis

Fluid intake for each 4-day test was averaged and expressed per 30 g body weight (the approximate weight of an adult mouse) per day. The body weight of each mouse was measured before and after each test series, averaged, and used to calculate the relative intake of each solution. We used measures of fluid intake rather than preference scores, because intake measures are not subject to a ceiling effect and related scaling problems (see Bachmanov et al., 1996).

Differences in solution intake due to strain (for parental strains) or reciprocal cross type (for F1 and F2 hybrids) and gender were evaluated by two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs). If an interaction effect was significant, post hoc least significant difference (LSD) tests were used to compare the means.

Analysis of Allelic Interaction Effects

The two characteristics of interaction between alleles of the same or different loci that we evaluated were dominance and heterosis. Significant deviation of the F1 and F2 mean values from a midparental value was considered dominance. Significantly higher (or lower) mean values for F1 or F2 than for a parental strain with a higher (or lower) score was considered heterosis.

The hypothetical midparental value (μmp) was calculated by

where μP1 is the mean of the 129 parental strain, and μP2 is the mean of the B6 parental strain. The variance associated with the midparental mean was calculated by

with the degrees of freedom given as the sum of the degrees of freedom derived from parental generations. Differences of F1 and F2 from the hypothetical midparental values or the parental strains were evaluated using Student’s t tests.

Analyses of Frequency Distributions

Two approaches were used to analyze the frequency distributions of intakes. In the first, the hypothesis of single-gene inheritance was tested using a method suggested by Collins (1967). For each taste solution, the observed distribution of the F2 mice was compared with the expected theoretical distribution. This was computed using the observed distributions in the parental strains and F1, assuming single-gene inheritance. The continuously distributed intake data were collapsed into intervals (e.g., interval 1, 0–1 ml of a solution; interval 2, 1–2 ml), so that each interval contained the numbers (counts) of mice that drank the corresponding amount of solution. The proportion of mice in each interval was calculated for the parental and F1 generations (piP1, piP2, piF1, where i is an interval number). Based on the assumption of single-gene inheritance, the proportion of F2 mice expected to fall into each interval was calculated as

Frequencies of the theoretical distributions were calculated as the total number of F2 hybrids multiplied by p’iF2. The expected distribution was compared with the observed distribution using a χ2 goodness-of-fit test (Ginsburg and Kulikov, 1983).

In the second approach, F2 distributions were analyzed to assess multimodality as described by MacLean et al. (1976). This method uses maximum likelihood to fit mixtures of two or three normal distributions to observed data and compares the fit obtained with that using one distribution. Intake of each taste solution was normalized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, using the mean and standard deviation of the F1 as the reference values and assuming single-gene inheritance (i.e., allele frequency = 0.5). The model parameters were estimated using the computer program SKUMIX (MacLean et al., 1976) with modifications described by Price et al. (1989) and Reed et al. (1995).

These two analyses allowed us to distinguish among the effects of a single gene (i.e., when a monogenic model is acceptable), a few genes with large effects (i.e., when a monogenic model is rejected but the F2 distribution is multimodal), and many genes with small effects (i.e., when a monogenic hypothesis is rejected and the F2 distribution is unimodal).

Analysis of Genetic and Environmental Components of Co-variation Among Taste Solution Intakes

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all possible pairs of traits within each generation. The total number of correlation coefficients analyzed was 40 (5 taste solutions by 2 parental strains and the F1 and F2 generations). A Bonferroni correction requires the level of statistical significance for this correlation matrix to be set at .05/40, or p < .00125, in order to provide p < .05 protection against any false correlation in the matrix. However, to avoid missing important relationships, a somewhat relaxed significance level p < .01 was used.

To distinguish between environmental and genetic contributions to phenotypic correlations, we used two approaches based on the assumption that phenotypic variance and covariance within the nonsegregating generations (parental strains and F1) is determined by nongenetic (environmental) factors, whereas phenotypic variance and covariance within the segregating F2 generation is due to both environmental and genetic factors. First, Pearson correlation coefficients within the F2 generation were directly compared with corresponding correlation coefficients within the nonsegregating generations. Second, genetic (rG) and nongenetic (rE) correlations were estimated, using an approach described by Falconer (1989). Phenotypic (total) variances and covariances were estimated based on data from the F2 . Environmental (nongenetic) variances and covariances were computed based on phenotypic variances and covariances of the parental strains and F1 hybrids using a proportion suggested by Mather and Jinks (1977). This proportion weights the contribution of parental and F1 genotypes to variability and covariability within the F2 as

Genetic variances and covariances were computed from total and environmental variances and covariances as

Genetic and environmental correlations were estimated as

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Solution Intake of Parental Strains

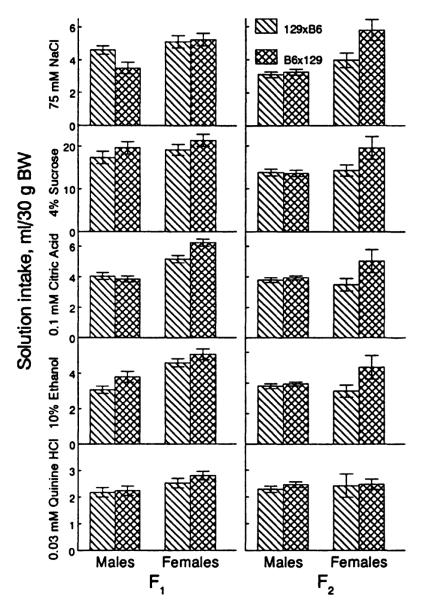

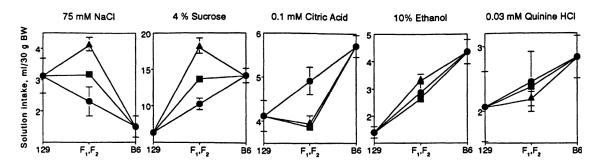

The 129 mice drank more NaCl and less sucrose, citric acid, ethanol, and quinine than did B6 mice, the strain differences being the same in males and females (Fig. 1, Table II). These data confirm and extend previous results with the 129 and B6 strains (Lush, 1984, 1989, 1991; Beauchamp and Fisher, 1993; Belknap et al., 1993; Bachmanov et al., 1996).

Fig. 1.

Solution intake of 129 and B6 mice. Vertical bars represent SE.

Table II.

ANOVA Results for Solution Intake of B6 and 129 Strains

| Effect of |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution | Strain | Gender | Strain × Gender |

| 75 mM NaCl | F(1,62)=36.4, P < .001 | F(1,62)=.01, NS | F(1,62)=2.78, NS |

| 4% sucrose | F(1,62)= 129.7 P < .001 | F(1,62)=16.5, p < .001 | F(1,62)=4.40, P = .040 |

| 0.1 mM citric acid | F(1,62)=21.4, P < .001 | F(1,62)=0.85, NS | F(1,62)=.18, NS |

| 10% ethanol | F(1,62)= 124.4, P < .001 | F(1,62)=4.67, P = .035 | F(1,62)=.068, NS |

| 0.03 mM quinine HCl | F(1,62)=7.62, P = .008 | F(1,62)=.13, NS | F(1,62)=.22, NS |

No differences between genders were found in consumption of NaCl, citric acid, and quinine. In both strains, females drank more ethanol than did males (Fig. 1, Table II). Sucrose intake was higher in female B6 than in male B6 mice (p < .001, post hoc LSD test), but it did not differ significantly between 129 female and 129 male mice. These results correspond to known gender differences in consumption of ethanol and sweet solutions by mice (McClearn and Rodgers, 1961; Eriksson, 1971; Stockton and Whitney, 1974; Pickett and Collins, 1975; Ramirez and Fuller, 1976).

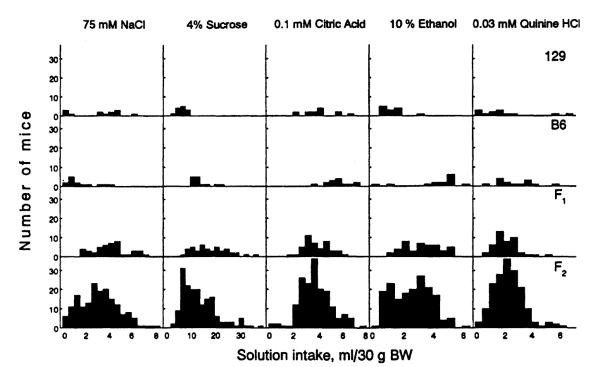

Solution Intake of Reciprocal Crosses

Sucrose and quinine intake was similar in the F1 and F2 mice from reciprocal crosses (Fig. 2). NaCl, citric acid, and ethanol intake differed between certain types of reciprocal crosses. F2 females from reciprocal crosses drank different amounts of NaCl [p = .004, post hoc LSD test; cross × gender interaction, F(1,197) = 5.81, p = .017]. F1 and F2 females from reciprocal crosses differed in citric acid intake [p < .001 and p = .005, respectively, post hoc LSD test; cross × gender interaction, F(1,97) = 6.87, p = .010, for F1 and F(1,197) = 5.56, p = .019, for F2]. These results do not correspond to patterns of reciprocal differences determined by maternal effects or by linkage to sex chromosomes (Jinks and Broadhurst, 1974), which is consistent with other studies on sucrose and NaCl intake (Pelz et al., 1973; Stockton and Whitney, 1974; Ramirez and Fuller, 1976; Sollars et al., 1990; Bachmanov and Dmitriev, 1992b).

Fig. 2.

Solution intake of reciprocal F1 and F2 hybrids: 129 × B6 cross originates from female 129 and male B6 mice; B6 × 129 cross originates from female B6 and male 129 mice. Vertical bars represent SE.

In both genders, F1 mice originating from 129 mothers drank slightly less ethanol than did those from B6 mothers [effect of cross type, F(1,97) = 5.03, p = .027]. This may be interpreted as a weak maternal effect that is present only in the F1. Although no differences between reciprocal crosses of mouse or rat strains have been found before (McClearn and Rodgers, 1961; Brewster, 1968; Pickett and Collins, 1975), some studies have indicated the possibility of maternal influences on ethanol intake (Komura et al., 1972; Randall and Lester, 1975).

Mode of Inheritance

Procedures to analyze the mode of inheritance were based on the analyses of data in parental strains and reciprocal crosses. First, because male and female mice of the parental strains and/or hybrids differed in intake of some solutions, the data for each gender were analyzed separately. Second, there were no significant differences between F1 and F2 males from reciprocal crosses for most characteristics tested, except ethanol intake by the F1 males. The difference in ethanol intake between reciprocal F1 hybrids (Fig. 2) was much smaller than both the difference between parental strains (Fig. 1) and the variability within F1 generation (Fig. 4). We thus analyzed both reciprocal types of F1 and F2 males together, as single groups.

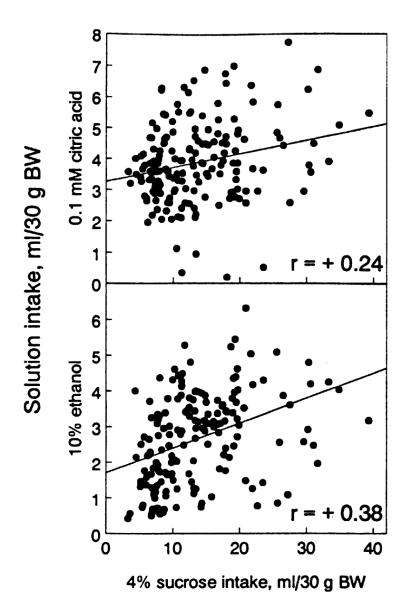

Fig. 4.

Frequency distribution of solution intake in male 129, B6, F1, and F2 mice. Bin sizes are 2 ml/30 g BW for sucrose intake and 0.5 ml/30 g BW for other solutions.

Allelic Interactions

Overall, dominance effects were largest for NaCl, sucrose, and citric acid intakes, and unless otherwise mentioned, the dominance and heterosis effects were similar for males and females. The F1 and F2 mice drank significantly more NaCl relative to the midparental value (p < .05; Fig. 3). The F1 males tended to drink more NaCl than did the 129 males, whereas the F1 and F2 females drank significantly more NaCl than did the 129 females (p < .05; cf. Figs. 1 and 2). This observation suggests the presence of directional dominance toward the 129 strain and a gender-specific heterosis effect.

Fig. 3.

Solution intake of male 129, B6, F1, and F2 mice. (●) Parental strains and midparental value; (▴) F1; (∎) F2. Vertical bars represent SE.

Sucrose intakes of the F1 and F2 hybrids were significantly higher than the midparental value (p < .02). The F1 males consumed significantly more sucrose than did the B6 males (p < .01). This demonstrates directional dominance of high sucrose consumption typical for the B6 strain, as well as a heterosis effect.

Citric acid intake of the F1 and F2 hybrids was lower than the midparental value (p < .01) and did not differ significantly from that of the 129 strain, suggesting full dominance of the 129 genotype.

Consumption of ethanol and quinine by F1 and F2 males did not differ from the midparental value, supporting an additive mode of inheritance. Unlike the males, the F1 females’ ethanol intake was significantly higher than the midparental value (p < .001) and was similar to intakes of the B6 mice (cf. Figs. 1 and 2), suggesting a gender-specific dominance effect.

Distribution Analyses

For parental strains, the distributions did not overlap for sucrose intake but did for the other solutions (Fig. 4). For all solutions tested, the observed F2 distributions differed significantly from the distributions expected from a single-gene model (Table III). Therefore, a single-gene model was rejected for all traits. Because sucrose intake distributions in parental strains did not overlap, we tested the possibility of a single-gene model by analyzing qualitative phenotypes of Low [less than 9.2 ml/30 g body weight (BW)] and High (9.2 ml/30 g BW and more) 4% sucrose solution intake. All 129 males were Low, and all B6 males were High. Of 44 F1 males, 41 were High and 3 were Low. This did not differ significantly from the frequencies expected for a dominantly inherited trait (44 High and 0 Low; χ2 = 0.205, NS). Based on a single-gene model with full dominance of the B6 allele, 25% of 171 F2 animals (n = 42.75) would be expected to have Low intakes and 75% (n = 128.25) would be expected to have High intakes. The observed frequencies (56 Low and 115 High) were significantly different from these expected frequencies (χ2 = 5.48, p < .02). Thus, a single-gene model for sucrose intake was rejected in both the quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Table III.

Comparison of Theoretical F2 Distributions for Solution Intake Expected Based on Single-Gene Model and F2 Distributions Observed Experimentally

| Solution | Bina | Expected frequency |

Observed frequency |

χ 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 mM NaCl | 0–2 | 51.5 | 45 | |

| 2–4 | 50.1 | 75 | 23.3*** | |

| 4–5 | 48.6 | 27 | ||

| >5 | 20.8 | 24 | ||

| 4% sucrose | 0–10 | 52.5 | 64 | |

| 10–15 | 53.9 | 48 | 15.8** | |

| 15–20 | 23.6 | 35 | ||

| >20 | 41.1 | 24 | ||

| 0.1 mM citric acid | 0–3 | 20.2 | 44 | |

| 3–4 4–5 | 51.2 42.6 | 59 39 | 43.4*** | |

| >5 | 57.1 | 29 | ||

| 10% ethanol | 0–1 | 19.5 | 20 | |

| 1–2 | 37.7 | 38 | ||

| 2–3 | 21.4 | 38 | 42.4*** | |

| 3–4 | 31.6 | 49 | ||

| >4 | 60.8 | 26 | ||

| 0.03 mM quinine HCI | 0–2 | 85.7 | 65 | |

| 2–3 | 50.7 | 66 | 10.4** | |

| >3 | 34.6 | 40 |

Bin borders are expressed as intake (ml/30 g BW).

p < .01.

p < .001.

In the F2 generation, the distributions of NaCl, sucrose, and ethanol intake were trimodal, the distribution of quinine intake was bimodal, and the distribution of citric acid was unimodal (Table IV).

Table IV.

Assessment of Multimodality of F2 Distributions for Solution Intakea

| Solution | Most likely number of distributions |

χ 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 75 mM NaCl | 2 vs. 1 | 19.4** |

| 3 vs. 2 | 10.2** | |

| 4% sucrose | 2 vs. 1 | 36.4** |

| 3 vs. 2 | 21.1** | |

| 0.1 mM citric acid | 2 vs. 1 | NS |

| 3 vs. 2 | NS | |

| 10% ethanol | 2 vs. 1 | 4.2* |

| 3 vs. 2 | 19.2** | |

| 0.03 mM quinine HCI | 2 vs. 1 | 16.5** |

| 3 vs. 2 | NS |

Hypothesis testing was carried out by comparing alternative (nested) models using a likelihood-ratio test. Twice the difference in the log likelihoods between models is distributed approximately as χ2, with the degrees of freedom equal to the difference between models in the number of free parameters. Because some tests of support for additional distributions involve constraints at boundaries rather than at interior regions of the parameter space, the assumed χ2 may hold only approximately.

p < .05.

p < .01.

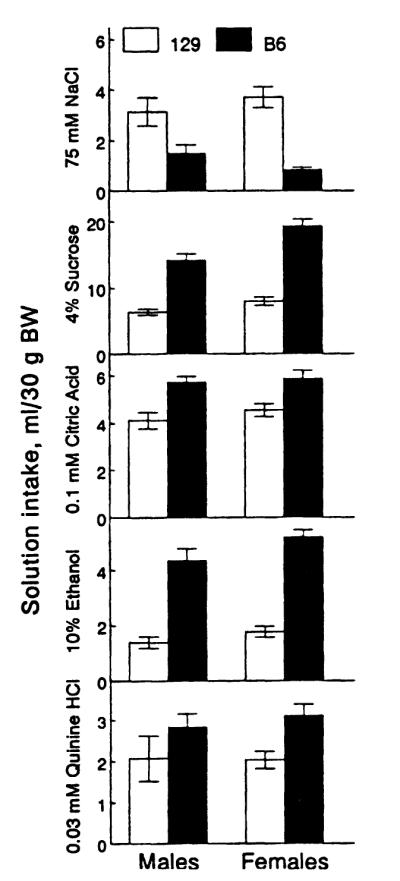

Analysis of Correlations Among Intakes of Taste Solutions

Correlations of sucrose intake with ethanol and with citric acid intake were significant and positive in the F2 generation (Table V, Fig. 5). The direction of these correlations corresponds to the differences between parental strains (the B6 mice had higher sucrose, ethanol, and citric acid intake than did the 129 mice), suggesting genetically determined links between the intake of sucrose, ethanol and citric acid. In the nonsegregating parental strains and F1, correlations between sucrose and both ethanol and citric acid intake were also positive (Table V), suggesting that unidentified non-genetic (environmental) factors also contributed to the covariation of these behaviors in the F2.

Table V.

Correlations Between Solution Intakes Within Parental Strains and F1 and F2 Hybrids

| Solution | 129 | B6 | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl–sucrose | 0.05 | −0.35 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| NaCl–citric acid | −0.28 | −0.24 | 0.06 | −0.08 |

| NaCl–ethanol | −0.07 | −0.35 | −0.16 | 0.20 |

| NaCl–quinine | 0.26 | −0.27 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Sucrose–citric acid | 0.75* | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.24* |

| Sucrose–ethanol | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.38** |

| Sucrose–quinine | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.01 |

| Citric acid–ethanol | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.33 | 0.03 |

| Citric acid–quinine | 0.48 | −0.03 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

| Ethanol–quinine | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

p < .01.

p < .001.

Fig. 5.

Codistribution between individual values of citric acid and ethanol intake with sucrose intake in F2.

Genetic and nongenetic components of the phenotypical correlations within the F2 were evaluated further by estimating rG and rE. For sucrose and ethanol intake rG = 1.44 [because rG and rE may have substantial error of estimation (Falconer, 1989), the absolute values may be more than 1], rE = 0.13; for sucrose and citric acid intake, rG = 0.48 and rE = 0.09. In both cases, rG was higher than rE, suggesting that genetic factors are more potent than nongenetic factors in determining the covariation of sucrose with ethanol and citric acid intake.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

None of the taste-related behaviors analyzed in the present study were consistent with a single-gene mode of inheritance. By assessing multimodality of the F2 distributions, we distinguished between traits influenced by a few genes with large effects (when the F2 distribution was multimodal) and traits influenced by many genes with small effects (when the F2 distribution was unimodal). The results for each flavor solution are discussed below.

Ethanol

Consistent with previous studies (McClearn and Rodgers, 1961; Fuller and Collins, 1967, 1972; Pickett and Collins, 1975; Phillips et al., 1994; Rodriguez et al., 1995), our results suggest that differences in ethanol consumption by the B6 and 129 strains depend on a few genes. In the present study, ethanol intake was inherited additively by males, whereas in females, a directional dominance of the B6 strain was present. In previous studies of ethanol consumption, contradictory results on allelic interaction were obtained (McClearn and Rodgers, 1961; Fuller, 1964; Brewster, 1968; Thomas, 1969; Eriksson, 1971; Pickett and Collins, 1975), which may be due to differences in the parental strains used, methods of testing, ethanol concentrations used, and scaling problems related to the analysis of preference or threshold scores. Thus, it is unclear to what extent this inconsistency is real or the result of methodological factors.

Consumptions of ethanol and sucrose were correlated in the F2 mice, resembling the intake patterns of the parental strains. Analysis of components of the phenotypic correlation in the F2 generation showed that both genetic and nongenetic factors contributed to this correlation, genetic effects being more potent. Results of other studies support the presence of a genetically determined link between the consumption of ethanol and that of sweet solutions (Belknap et al., 1993; Overstreet et al., 1993; Stewart et al., 1994; Phillips et al., 1994). This may result from either pleiotropy or linkage. Several common physiological mechanisms could underlie pleiotropism, including the sensitivity to the sweet-taste component of ethanol flavor (Kiefer and Lawrence, 1988), common signals related to caloric value (Gentry and Dole, 1987), or common brain mechanisms (Hubell et al., 1991; Pucilowski et al., 1992).

Previous work has suggested a relationship between excess ethanol consumption and a lower sensitivity to bitter or aversion to NaCl (Grupp et al., 1991; Pelchat and Danowski, 1992; Bachmanov et al., 1996). However, we found no cosegregation in the F2 generation between intake of ethanol and intake of quinine or NaCl, suggesting that independent genes fixed during inbreeding of the parental strains are responsible for these associations in the 129 and B6 mice.

Sucrose

Our analyses suggest that the difference in sucrose intake between the 129 and the 86 strains depends on a few genes, with the B6 genotype being dominant. Several genes have been hypothesized to influence sweet taste (Ninomiya and Funakoshi, 1993), including Sac [saccharin preference (Fuller, 1974)] and dpa [d-phenylalanine sweetness (Ninomiya et al., 1987).] C57BL/6 mouse substrains carry a dominant allele of Sac responsible for high intake and preference of sweet substances (Fuller, 1974; Lush, 1989) and a dominant allele of dpa that determines an ability to taste the sweetness of d-phenylalanine (Ninomiya et al., 1987; Ninomiya and Funakoshi, 1993). Unlike C57BL/6 mice, 129 substrains have low preferences for saccharin and sucrose (Lush, 1989; Belknap et al., 1992, 1993; Bachmanov et al., 1996) and do not discriminate d-phenylalanine from water in preference tests (Capeless and Whitney, 1995; Bachmanov et al., unpublished). These findings suggest that the difference in sucrose intake between the B6 and the 129 mice may depend on different alleles at at least two loci, Sac and dpa (see also Capeless and Whitney, 1995). Our analyses do not rule out the possibility that other genes are involved, a conclusion consistent with the results of Phillips et al. (1994).

Citric Acid

Citric acid intake in the 129 and B6 strains appeared to be influenced by many genes with small effects because a single-gene model was rejected, and the F2 distribution was unimodal. The overall effect of 129 alleles influencing citric acid intake resulted in full directional dominance over B6 alleles.

Consumption of citric acid and sucrose cose-gregated among the F2 mice, resembling the intake patterns of the parental strains. As with ethanol and sucrose consumption, the genetic component of the correlation between citric acid and sucrose intake was stronger than the environmental component. This genetic correlation may be due to a common mechanism for effects of the citrate anion and sweet stimuli on cellular gustatory responses (Gilbertson et al., 1995).

Quinine

According to the distribution analyses, a few genes appear to determine quinine intake of the 129 and B6 strains, which is consistent with the results of other studies (Gora-Maslak et al., 1991; Boughter et al., 1992). One locus, influencing quinine consumption by 129 and B6 mice, may be Qui (taste sensitivity to quinine), with three probable alleles. The 129 strain carries the Quia allele of high sensitivity to quinine, and the B6 strain carries the Quib allele of intermediate sensitivity (Lush, 1984). Another locus influencing quinine preference, Soa [sucrose octaacetate aversion (Boughter et al., 1992; Whitney and Harder, 1994)], is probably not involved in the difference between the 129 and the B6 strains, because they carry the same Soa allele (Lush, 1981). Moreover, both Qui and Soa were linked to chromosome 6 with a distance about 20 cM separating them (Azen, 1988; Capeless et al., 1992), suggesting that other independent loci are also involved in the strain difference.

An additive mode of inheritance of quinine consumption was found in the F1 and F2 hybrids in our study, which corresponds to the results of Lush (1984) for similar quinine concentrations.

NaCl

Our analyses of NaCl intake suggest that this behavior in the 129 and B6 strains depends on a few genes and that NaCl avoidance by the B6 strain is inherited as a recessive trait. This is consistent with studies on the F-344 and SHR rat strains (Sollars et al., 1990; Bachmanov and Dmitriev, 1992a). It seems likely that NaCl consumption in most mouse and rat strains depends on dominant wild-type genes, whereas deviations in B6 mice and F-344, or SHR rats are due to recessive mutations.

To summarize, our results and analyses confirm that the behavioral responses to ethanol and exemplars of each taste quality depend on individual sets of a few to many genes. These gene sets partly overlap between sucrose, ethanol, and citric acid intakes. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the higher ethanol intake by B6 mice depends, in part, on higher hedonic attractiveness of its sweet-taste component; however, other mechanisms may also underlie the genetic correlation between ethanol and sucrose intake. The 129 and B6 mouse strains and associated hybrids will provide valuable tools for the identification of genes influencing solution intake.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grant DC 00882 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (G.K.B.), Howard Heinz Endowment (A.A.B.). Weight Watchers Foundation (D.R.R.), and NIH R01-DK 44073 and R01-DK 48095 (R.A.P.). Portions of this work were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Chemoreception Sciences, Sarasota, Florida, April 1995.

REFERENCES

- Azen EA. Linkage studies of genes for salivary proline-rich proteins and bitter taste in mouse and human. In: Wysocki CJ, Kare MR, editors. Chemical Senses. vol. 3: Genetics of Perception and Communication. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1988. pp. 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Dmitriev Yu.S. Genetic analysis of some behavioral and physiological traits in hybrids between hypertensive and normotensive rats: Analysis of the inheritance nature. Genetika. 1992a;28:150–159. (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Dmitriev Yu. S. Genetic analysis of some behavioral and physiological traits in hybrids between hypertensive and normotensive rats: Analysis of reciprocal differences. Genetika. 1992b;28:120–127. (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Tordoff MG, Beauchamp GK. Strain differences in salt appetite in mice. Abstracts of the 2nd Independent Meeting of the SSIB; Hamilton, Canada. 1994. pp. A–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Tordoff MG, Beauchamp GK. Ethanol consumption and taste preferences in C57BL/6ByJ and 129/J mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball DM, Murray RM. Genetics of alcohol misuse. Br. Med. Bull. 1994;50:18–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp GK, Fisher AS. Strain differences in consumption of saline solutions by mice. Physiol. Behav. 1993;54:179–184. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90063-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Plomin R, McClearn GE, Sampson KE, O’Toole LA, Gora-Maslak G. Single-locus control of saccharin intake in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred (RI) mice: some methodological implications for RI strain analysis. Behav. Genet. 1992;22:81–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01066794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Young ER. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF02244901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughter JD, Harder DB, Capeless CG, Whitney G. Polygenic determination of quinine aversion among mice. Chem. Senses. 1992;17:427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster DJ. Genetic analysis of ethanol preference in rats selected for emotional reactivity. J. Hered. 1968;59:283–286. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeless CG, Whitney G. The genetic basis of preference for sweet substances among inbred strains of mice: preference ratio phenotypes and the alleles of the Sac and dpa loci. Chem. Senses. 1995;20:291–298. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeless CG, Whitney G, Azen EA. Chromosome mapping of Soa, a gene influencing gustatory sensitivity to sucrose octaacetate in mice. Behav. Genet. 1992;22:655–663. doi: 10.1007/BF01066636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL. A general nonparametric theory of genetic analysis. I. Application to classical cross. Genetics. 1967;56:551. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K. Inheritance of behaviour towards alcohol in normal and motivated choice situations in mice. Ann. Zool. Fennici. 1971;8:400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. 3rd ed J. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller JL. Measurement of alcohol preference in genetic experiments. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1964;57:85–88. doi: 10.1037/h0043100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller JL. Single-locus control of saccharin preference in mice. J. Heredity. 1974;65:33–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller JL, Collins RL. Ethanol preference in hybrids between a low and a high preference strain of mice. Genetics. 1967;56:560–561. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller JL, Collins RL. Ethanol consumption and preference in mice: a genetic analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1972;197:42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb28116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry RT, Dole VP. Why does a sucrose choice reduce the consumption of alcohol in C57BL/6J mice? Life Sci. 1987;40:2191–2194. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson TA, Gilbertson DM, Monroe WT, Milliet JR, Caprio J. Abstr. of the AChemS-XVII. Sarasota, Florida: Apr, 1995. Citrate enhances behavioral and cellular gustatory responses to sweet and amino acid stimuli in mammals; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg E. Kh., Kulikov AV. Verification of monogenic hypotheses in the hybridological analysis of quantitative characters. Genetika. 1983;19:571–576. (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gora-Maslak G, McClearn GE, Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Belknap JK, Plomin R. Use of recombinant inbred strains to identify quantitative trait loci in psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:413–424. doi: 10.1007/BF02245643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp LA, Perlanski E, Stewart RB. Regulation of alcohol consumption by the renin-angiotensin system: a review of recent findings and a possible mechanism of action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1991;15:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubell CL, Marglin SH, Spitalnic SJ, Abelson ML, Wild KD, Reid LD. Opioidergic, serotoninergic, and dopaminergic manipulations and rats’ intake of a sweetened alcoholic beverage. Alcohol. 1991;8:355–367. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(91)90573-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks JL, Broadhurst PL. How to analyse the inheritance of behaviour in animals—the biometrical approach. In: van Abeelen JHF, editor. The Genetics of Behaviour. North-Holland.; Amsterdam: 1974. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer SW, Lawrence GJ. The sweet-bitter taste of alcohol: Aversion generalization to various sweet-quinine mixtures in the rat. Chem. Senses. 1988;13:633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Komura S, Ueda M, Kobayashi T. Effects of foster nursing on alcohol selection in inbred strains of mice. Q. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1972;33:494–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush IE. The genetics of tasting in mice. I. Sucrose octaacetate. Genet. Res. 1984;44:151–160. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300026355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush IE. The genetics of tasting in mice. III. Quinine. Genet. Res. 1984;44:151–160. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300026355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush IE. The genetics of tasting in mice. VI. Saccharin, acesulfame, dulcin and sucrose. Genet. Res. 1989;53:95–99. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300027968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush IE. The genetics of bitterness, sweetness, and saltiness in strains of mice. In: Wysocki CJ, Kare MR, editors. Chemical Senses. vol. 3: Genetics of Perception and Communication. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1991. pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Mather K, Jinks JL. Introduction to Biometrical Genetics. Cornell University Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean CJ, Morton NE, Elston RC, Yee S. Skewness in commingled distributions. Biometrics. 1976;32:695–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn GE, Rodgers D. Genetic factors in alcohol preference of laboratory mice. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1961;54:116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nachman M, Larue C, Le Magnen J. The role of olfactory and orosensory factors in the alcohol preference of inbred strains of mice. Physiol. Behav. 1971;6:53–95. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya Y, Funakoshi M. Genetic and neurobehavioral approaches to the taste receptor mechanism in mammals. In: Simon SA, Roper SO, editors. Mechanisms of Taste Transduction. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1993. pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya Y, Higashi T, Mizukoshi T, Funakoshi M. Genetics of the ability to perceive sweetness of d-phenylalanine in mice. Annl. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;510:527–529. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet DH, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Rezvani AH, Murelle L, Halikas JA, Janowsky DS. Saccharin intake predicts ethanol intake in genetically heterogeneous rats as well as different rat strains. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1993;17:366–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat ML, Danowski S. A possible generic association between PROP-tasting and alcoholism. Physiol. Behav. 1992;51:1261–1266. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90318-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelz WE, Whitney G, Smith JC. Genetic influences on saccharin preference of mice. Physiol. Behav. 1973;10:263–265. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Crabbe JC, Metten P, Belknap JK. Localization of genes affecting alcohol drinking in mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1994;18:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett RA, Collins AC. Use of genetic analysis to test the potential role of serotonin in alcohol preference. Life Sci. 1975;17:1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RA, Sorensen TI, Stunkard AJ. Component distributions of body mass index defining moderate and extreme overweight in Danish women and men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989;130:193–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucilowski O, Rezvani AH, Janowsky DS. Suppression of alcohol and saccharin preference in rats by a novel Ca2− channel inhibitor, Goe 5438. Psychopharmacology. 1992;107:447–452. doi: 10.1007/BF02245174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez I, Fuller JL. Genetic influence on water and sweetened water consumption in mice. Physiol. Behav. 1976;16:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall CL, Lester D. Cross-fostering of DBA and C57Bl mice: Increase in voluntary consumption of alcohol by DBA weanlings. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1975;36:973–980. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DR, Bartoshuk LM, Duffy V, Marino S, Price RA. PROP tasting: determination of underlying thresholds distributions using maximum likelihood. Chem. Senses. 1995;20:529–533. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LA, Plomin R, Blizard DA, Jones BC, McClearn GE. Alcohol acceptance, preference, and sensitivity in mice. II. Quantitative trait loci mapping analysis using BXD recombinant inbred strains. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995;19:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollars SI, Midkiff EE, Bernstein IL. Genetic transmission of NaCl aversion in the Fisher-344 rat. Chem. Senses. 1990;15:521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Russell RN, Lumeng L, Li T-K, Murphy JM. Consumptions of sweet, salty, sour, and bitter solutions by selectively bred alcohol-preferring and alcohol-nonpreferring lines of rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1994;18:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockton MD, Whitney G. Effects of genotype, sugar, and concentration on sugar preference of laboratory mice (Mus musculus) J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1974;86:62–68. doi: 10.1037/h0035929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. Selection and avoidance of alcohol solutions by two strains of inbred mice and derived generations. Q. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1969;30:849–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney G, Harder DB. Genetics of bitter perception in mice. Physiol. Behav. 1994;56:1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]