Abstract

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is an idiopathic non-malignant disease of large airways featured by submucosal cartilaginous to osseous nodules overlying the cartilaginous rings, which may be focal or diffuse. Clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic to symptoms like breathlessness, recurrent chest infections, cough and hemoptysis. Due to the lack of awareness of this disease, it remains an under recognized entity. We are describing the computed tomography and bronchoscopic findings of two recently diagnosed cases at our institute. The purpose of this report is to familiarize radiologists with imaging appearance of this condition, with the goal of increasing clinical suspicion of this uncommon condition.

Keywords: Calcification, CT, Osteocartilaginous nodules, Trachea, Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, TPO

CASE REPORT

CASE REPORT 1

A 28-year-old non-smoker male presented with the chief complaints of cough with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing of 6 year duration. Also, he had history of nasal crusting with foul smelling nasal discharge. There was no history of hemoptysis, loss of appetite, weight loss or fever. There was no history of tuberculosis in past. Patient was being treated with inhaled steroids and bronchodilators, along with antibiotics and nasal decongestants in past. On physical examination, there was no significant abnormality. Chest radiograph was unremarkable (Fig. 1). Laboratory evaluation showed eosinophilia with absolute eosinophil count of 780 cells/μl (normal range 50–350 cells/μl). An otorhinolaryngologist’s consultation was sought and a CT (Computed tomography) of paranasal sinus was done. CT scan of the paranasal sinuses showed soft tissue opacification of bilateral maxillary, ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses with atrophy of the nasal turbinates (Fig. 2). Thickening and sclerosis of the bony wall of sphenoid sinus was also noted (Fig. 2B). Based on the clinical and imaging findings a diagnosis of atrophic rhinitis was made. For respiratory symptoms spirometry was performed, which was within normal limits. Because of uncontrolled symptoms, patient was screened for aspergillus hypersensitivity. Aspergillus skin test was positive therefore further evaluation for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) was performed. Total IgE was 4460 IU/ml (normal range <100 IU/ml). CT scan of the chest was ordered to evaluate tracheobronchial tree and lung parenchyma. CT scan did not reveal any parenchymal abnormality or bronchiectasis; however, CT images showed presence of calcification of the tracheal and bronchial wall with irregular inner lining (Fig. 3–5). No abnormal soft tissue lesion or mediastinal adenopathy was seen. A fiberoptic bronchoscopy was done to look for the cause of extensive calcification. It showed diffuse mucosal nodular infiltration of trachea and both major bronchi which was hard on touch (Fig. 6). Bronchial lavage was negative for acid fast bacilli or any other pathogen. Diagnosis of Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica was confirmed on pathological examination of the bronchial biopsy, which showed multiple bits of bronchial mucosa with presence of cartilage, calcification and lamellar-type of bone (Fig. 7). Underlying stroma showed mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Specific IgE to A. fumigatus was elevated (14.3 kU/L; normal range < 0.35 kU/L). With history of bronchial asthma, patient was diagnosed as a case of ABPA-S. Presently, patient is on oral steroid and symptomatic treatment.

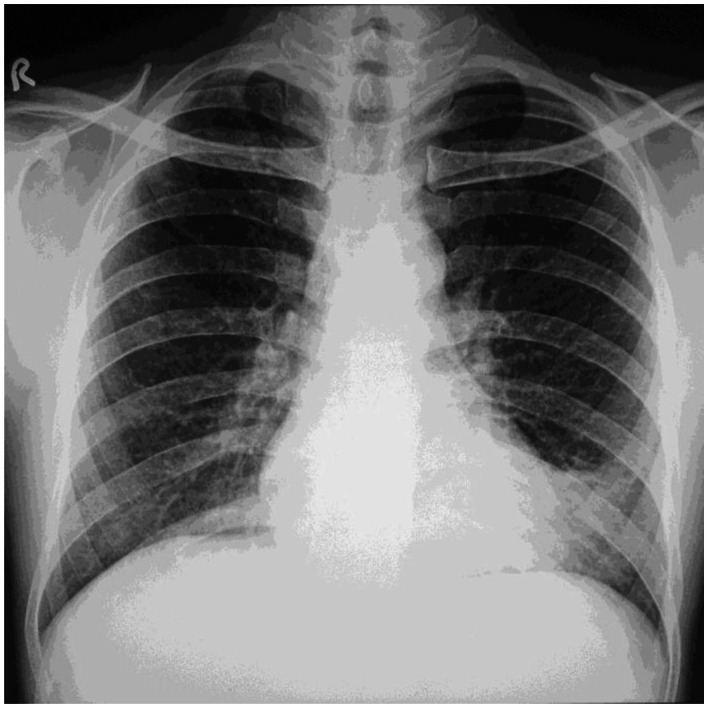

Figure 1.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. Chest radiograph is unremarkable. (Chest radiograph, PA view, erect posture)

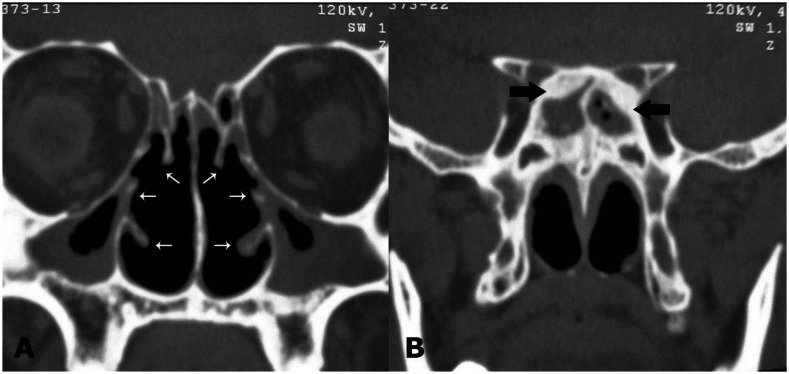

Figure 2.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. (A) Non-contrast coronal CT image of paranasal sinus shows soft tissue opacification of bilateral maxillary sinuses with atrophy of all nasal turbinates (white arrows). (B) Soft tissue opacification of sphenoid sinus with sclerosis of bony walls (arrows). (64-Channel Multidetector Brilliance CT, Philips Medical systems, 120 kV, 400 mAs, 1.0 mm coronal reformation and window width/level of 2500/700 HU)

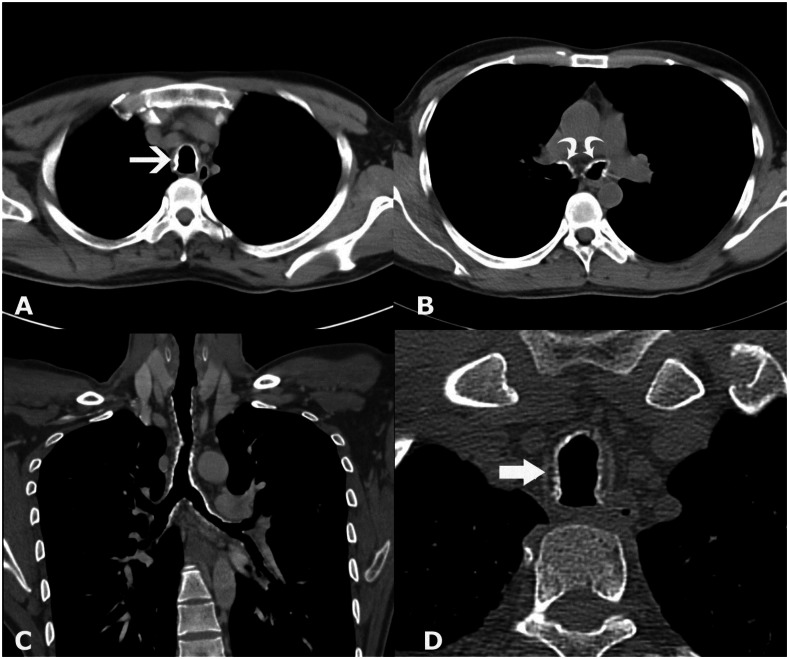

Figure 3.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. (A) Non-contrast axial CT section shows presence of nodular wall calcification of inner tracheal lining (white arrow) with sparing of posterior wall. (B) Lower sections reveal nodular calcification in main bronchi (arrows). (C) Coronal reconstructed image reveals the extent of involvement of tracheobronchial tree. Lower two third trachea and main bronchi are affected with relatively spared upper third of trachea. (D) High resolution zoomed image shows location of calcification internal to cartilage (arrow). (128-channel MDCT scanner SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Medical Solutions, 120 kV, automatic mAs, detector collimation 128 × 0.6 mm, window width/level of 360/60 HU, 0.6 mm slice thickness for high resolution image and 3 mm for other images).

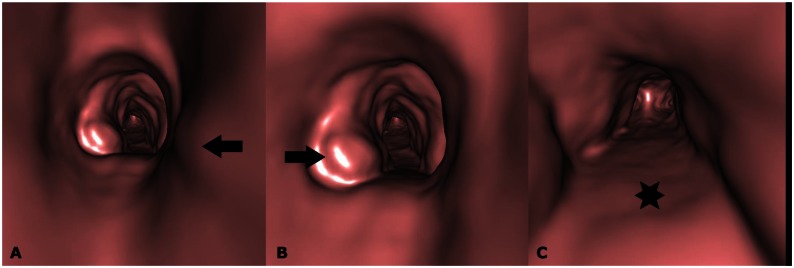

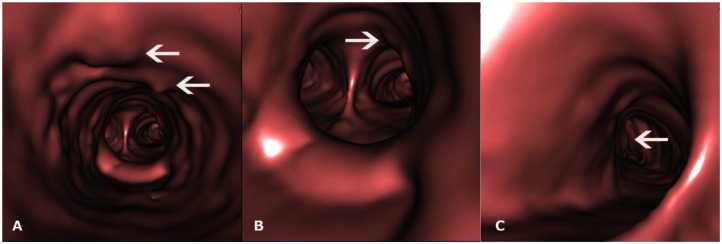

Figure 5.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. (A, B, C) CT-generated virtual bronchoscopy images show multiple nodular projections in the lumen (arrows) with sparing of posterior wall (star). (128-MDCT scanner SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Medical Solutions, 120 kV, automatic mAs, detector collimation 128 × 0.6 mm, Created in Syngo work station, Siemens, from 1 mm reconstructed images with smooth kernel).

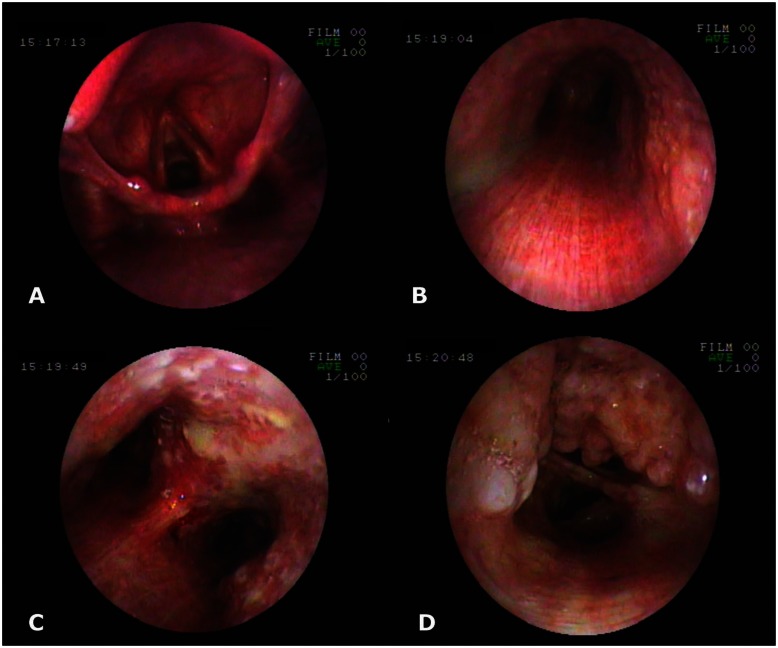

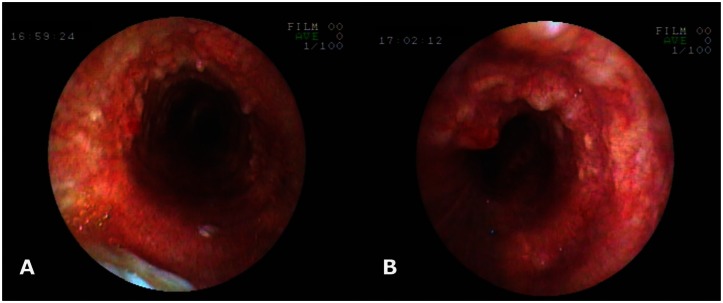

Figure 6.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy pictures reveal mucosal nodularity and deposits in tracheobronchial tree; larynx and posterior wall of trachea are not affected. Photograph at the level of larynx (A), trachea (B), carina (C) and intermediate bronchus (D). (Fiberoptic bronchoscope, Fujinon)

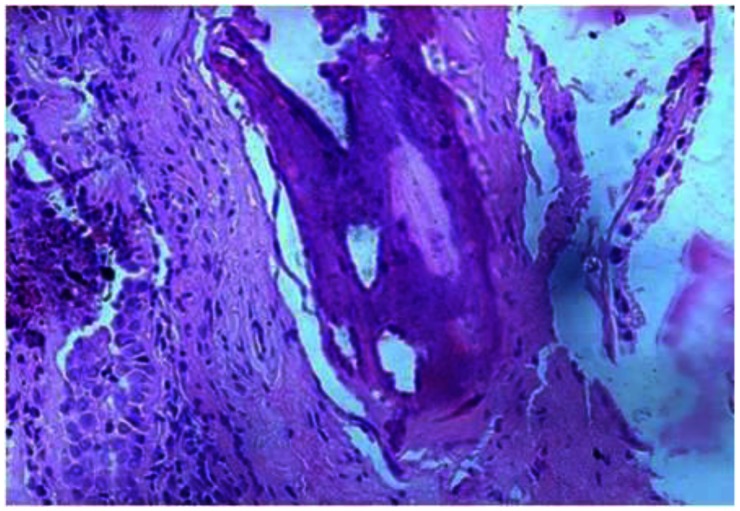

Figure 7.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. Microscopic appearance shows bronchial mucosa lined by respiratory epithelium and display presence of calcification and lamellar-type of bone (H & E ×400).

CASE REPORT 2

A 42-year-old non-smoker male was referred to our outpatient from Gastroenterology department where he was being followed up for chronic HBV related hepatitis, with complaint of mild hemoptysis off and on for 3 years. He had occasional dry cough. There was no history of fever or dyspnoea. For the above complaints in past, he was treated conservatively. There was no past history of pulmonary tuberculosis or bronchial asthma. General physical, cardiovascular and respiratory system examinations were normal. Complete blood counts, coagulation profile and clinical chemistry were also within normal limits. Chest radiograph was unremarkable (Fig. 8). Computed tomography of the chest was unremarkable except for some fibrotic opacities in the right upper lobe. However, focal areas of irregular nodularity and calcification were noted on left lateral wall of trachea and left bronchus (Fig. 9, 10). To localize the site of hemoptysis and for further characterization of CT findings, fiberoptic bronchoscopy was done which revealed diffuse white nodularity of the tracheobronchial tree, more on left side (Fig. 11). Histopathological features were consistent with Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica.

Figure 8.

42-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with hemoptysis. Chest radiograph is unremarkable. (Chest radiograph, PA view, erect posture)

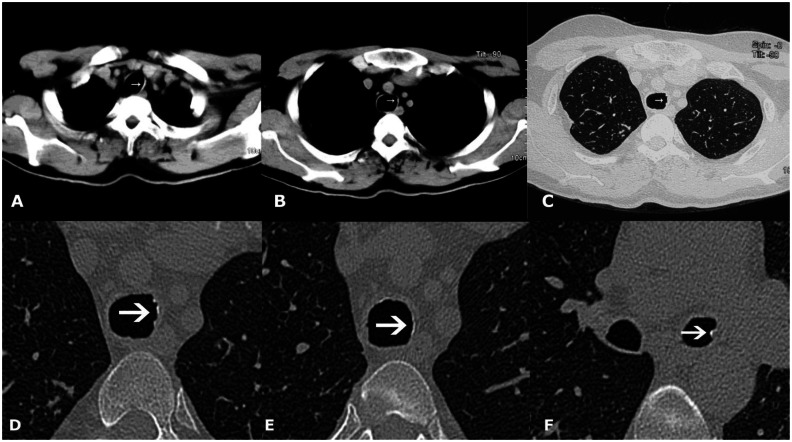

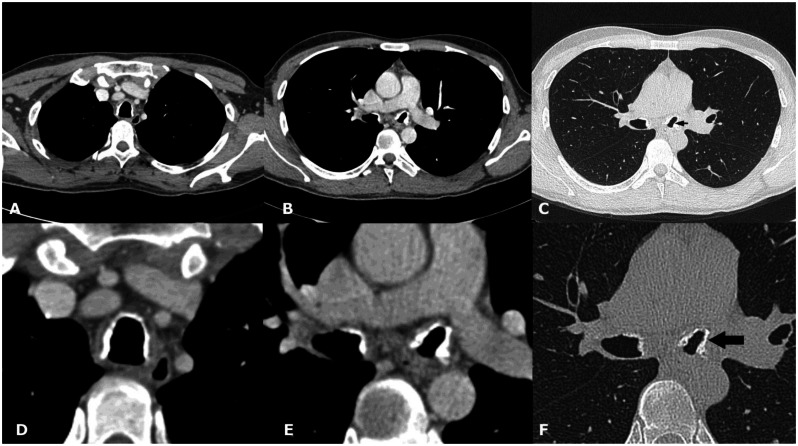

Figure 9.

42-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with hemoptysis. (A, B) Non-contrast axial soft tissue window CT images reveal faint calcification on the left lateral wall of trachea (white arrow). (C) High resolution lung window CT image reveals subtle nodularity of inner tracheal surface (arrow). (D, E, F) Magnified high resolution images of trachea and left bronchi showing nodular calcification (arrows). (128-MDCT scanner SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Medical Solutions, 120 kV, automatic mAs, detector collimation 128 × 0.6 mm, 3 mm reformation and window width/level of 360/60 HU for soft tissue images, 0.6 mm slice thickness and width/level of 1600/−600 HU for lung window image, 0.6 mm magnified high resolution images).

Figure 10.

42-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with hemoptysis. (A, B, C) CT- generated virtual bronchoscopy images show multiple small nodules projecting from inner tracheal and left bronchial surface (arrows). (128-MDCT scanner SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Medical Solutions, 120 kV, automatic mAs, detector collimation 128 × 0.6 mm, Created in Syngo work station, Siemens, from 1 mm reconstructed images with smooth kernel).

Figure 11.

42-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with hemoptysis. Fiber-optic bronchoscopy pictures revealing mucosal nodularity and deposits. Photograph at the level of trachea (A) and left main bronchus (B). (Fiberoptic bronchoscope, Fujinon)

DISCUSSION

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (TPO) is a benign chronic disease characterized by the presence of submucosal osteocartilaginous nodules in the tracheobronchial tree [1, 2]. Although the actual incidence of this entity remains unknown, it may be significantly more than what we are led to consider. The reported incidence is 1 in 400 cases in autopsy series, while it varies from 4 of 550 to 9 of 2,180 during bronchoscopy examinations placing the incidence at 2 to 7 cases in 1000 [3]. At our institute in year 2011, 2 out of 280 patients who underwent bronchoscopy were diagnosed as TPO. It is usually diagnosed in sixth or seventh decade of life but a case in a 12-year-old child has been reported [1]. There are conflicting observations from various studies regarding sex predilection in the past, but a slight male predominance has been noted by many investigators [1, 4]. Until now, approximately 400 cases have been reported worldwide [4–15].

Still, the cause of TPO remains elusive but the association with chronic infections, inflammation, trauma, amyloidosis and silicosis has been hypothesized [2]. TPO has been linked with atrophic rhinitis (ozena), a disease characterized by nasal mucopurulent discharge and crusting as seen in our first case [16, 17]. To the best of our knowledge, association of TPO with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) has never been reported in the past. It is uncertain whether the association of TPO with ABPA is a coincidence or chronic inflammation of the airways in ABPA has incited the formation of nodules. Two theories have been postulated regarding the pathogenesis of this disease [1, 2]. First, the Virchow’s theory states that ecchondromas are the initial lesions which undergo calcification and ossification leading to nodule formation [18]. Second is the metaplastic theory by Aschoff-Freiburg postulating the ossification of elastic connective tissue [19].

TPO has a variable clinical presentation, and it may be clinically silent at times. Symptoms are nonspecific and may include chronic cough, dyspnoea, hemoptysis, wheezing and recurrent respiratory infections [1, 2]. Many times patients with TPO are labeled to have asthma or chronic bronchitis until a bronchoscopic examination is performed. Pulmonary symptoms are due to the narrowing of airways as a result of confluent submucosal nodules and loss of normal ciliated respiratory epithelium. It has been hypothesized that the cough results from combination of factors, including turbulent airflow, increased airway sensitivity, and impaired ciliary clearance [20]. Although TPO is usually a benign disorder, over time significant disease progression has been reported in about 17% of cases [3].

If central airway abnormalities are suspected, further imaging of tracheobronchial tree is best performed with CT scan [21]. In case of TPO, CT scan demonstrates a characteristic pattern of calcified nodules arising from the anterior and lateral aspect of the inner tracheal wall protruding into lumen, in severe form resulting in luminal narrowing [21–23]. Tracheomalacia is not present. Although these lesions may extend anywhere from the larynx to the peripheral bronchi, they are more commonly seen in distal two third of trachea and proximal bronchi. Since these nodules arise from cartilage, therefore posterior membranous wall of trachea is typically spared; which distinguishes it from many other airway diseases such as tracheobronchial amyloidosis, Wegener granulomatosis etc. Focal form of TPO has also been described causing obstructive collapse [7, 8].

Although CT may miss early changes, it is the imaging modality of choice for this condition. CT scan showed classical picture of TPO in our first case but not in second one. This could be explained by the fact that second case had a less extensive involvement. However, CT has shown focal nodularity and calcification in trachea for which this patient was subjected to bronchoscopy leading to the diagnosis. CT-generated virtual bronchoscopy is a novel post processing technique that allows non-invasive visualization of the tracheobronchial tree [24]. Although it can show the endoluminal lesions, it cannot assess the mucosal details and tissue sample could not be obtained. Virtual bronchoscopy is not a replacement for actual bronchoscopy but it can be used as an additional tool during CT evaluation of the tracheobronchial tree. Even though imaging studies may give clue to the diagnosis, bronchoscopy is the most definitive diagnostic test. The bronchoscopic appearance itself is diagnostic and is characterized by the multiple, varied size smooth whitish nodules [23]. These nodules are hard on touch and gives gritty sensation while passing the scope through the lumen. Biopsy of the nodules is not often required and is difficult to obtain as forceps slips off on the surface of hard nodules. As the bronchoscopic finding may be confused with airway malignancy, awareness of this condition is important to prevent unnecessary invasive procedures.

Common causes of calcification of tracheal and bronchial walls are TPO, relapsing polychondritis, amyloidosis, and old age [22, 23]. But unlike TPO, the amyloidosis does not spare the posterior wall of the trachea. Although relapsing polychondritis may have a similar distribution as TPO, it characteristically presents with thickened and deformed cartilage with or without calcification, and the inner wall is smooth without discrete intraluminal nodules formation. The appearance of calcification in TPO is much more irregular than the cartilage calcification noted in healthy elderly individuals.

There is no definitive treatment available for TPO, hence treatment is only offered to symptomatic cases [1, 4]. Management includes maintaining airway humidity, reduction of airway irritation and treatment of respiratory infections. In severe cases like airway stenosis, various bronchoscopic interventions have been tried like removal of nodules by forceps, laser ablation, cryotherapy and external beam irradiation [1, 4]. Prognosis is generally good but it is related with degree of airway involvement and luminal narrowing [1].

To conclude, TPO is not as rare as it was earlier thought to be and whose true prevalence should be determined. As advanced CT scanners and bronchoscopy facilities have become more widely available, an increased number of these cases are being diagnosed now. By familiarizing radiologists and pulmonologists with the imaging appearance of this entity, less number of these cases will go unrecognized and appropriate treatment will be offered to these patients.

TEACHING POINT

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is a rare benign disease of tracheobronchial tree characterized by the presence of submucosal osteocartilaginous nodules. Presence of nodular calcification of inner tracheal lining on imaging should raise the suspicion of this condition and a bronchoscopy examination should be done for confirmation.

Figure 4.

28-year-old male with Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica presenting with expectoration, breathlessness and wheezing. (A, B) Contrast enhanced axial CT images show normal enhancement of mediastinal vascular structures. (C) Axial CT lung window image more clearly depicts the nodular inner surface and narrowing of bronchi (arrow). Lung parenchyma is normal. (D) Magnified image corresponding to image A. (E) Magnified image corresponding to image B. (F) Magnified image corresponding to image C. (128-MDCT scanner SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Medical Solutions, 120 kV, automatic mAs, detector collimation 128 × 0.6 mm, 3 mm reformation and window width/level of 360/60 HU for soft tissue images, 0.6 mm slice thickness and width/level of 1600/−600 HU for lung window image, 80 c.c. of 300 mg/ml iodine concentration non- ionic contrast given by hand injection).

Table 1.

Summary table of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica

| Etiology | Unknown, but association with chronic infections, inflammation, trauma, amyloidosis and silicosis has been hypothesized. |

| Incidence | 2 to 7 cases in 1000 bronchoscopies. |

| Gender ratio | Slight male predominance |

| Age predilection | Usually sixth or seventh decade of life. |

| Risk factors | No definite risk factor identified. |

| Treatment | No definitive treatment, management includes maintaining airway humidity, reduction of airway irritation and treatment of respiratory infections. In severe cases with airway stenosis, removal of nodules by forceps, laser ablation, cryotherapy and external beam irradiation has been tried. |

| Prognosis | Prognosis is generally good but related with degree of airway involvement and luminal narrowing. |

| Imaging findings | Chest radiographs usually unremarkable. CT scan

|

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica

| Disease | Imaging findings | Bronchoscopic findings |

|---|---|---|

| Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica |

|

|

| Relapsing polychondritis |

|

|

| Tracheobronchial amyloidosis |

|

|

| Normal age related calcification |

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- ABPA

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

- ABPA-S

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis-Seropositive

- CT

Computed tomography

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- TPO

Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica

REFERENCES

- 1.Prakash UB. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Apr;23(2):167–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chroneou A, Zias N, Gonzalez AV, Beamis JF., Jr Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. An underrecognized entity? Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008 Jun;69(2):65–9. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2008.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain K, Gilbert S. Tracheopathia osteochondroplastica. Clin Med Res. 2003 Jul;1(3):239–42. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbardarjani HR, Radpey B, Kharabian S, Masjedi MR. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: presentation of ten cases and review of the literature. Lung. 2008 Sep-Oct;186(5):293–7. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthwal MS, Chatterji RS, Mehta A. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004 Jan-Mar;46(1):43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zack JR, Rozenshtein A. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: report of three cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002 Jan-Feb;26(1):33–6. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doshi H, Thankachen R, Philip MA, Kurien S, Shukla V, Korula RJ. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica presenting as an isolated nodule in the right upper lobe bronchus with upper lobe collapse. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005 Sep;130(3):901–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigematsu Y, Sugio K, Yasuda M, et al. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica occurring in a subsegmental bronchus and causing obstructive pneumonia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 Nov;80(5):1936–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bruin HG, Lamers RJ. Tracheal nodularity due to tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. JBR-BTR. 2005 May-Jun;88(3):120–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Khushman HM. Recurrent hemoptysis from diffuse tracheal nodularity due to tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. Ann Saudi Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;27(5):378–80. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willms H, Wiechmann V, Sack U, Gillissen A. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: a rare cause of chronic cough with haemoptysis. Cough. 2008 Jun 30;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swamy TL, Hasan A. Tracheopathia osteoplastica presenting with haemoptysis in a young male. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2010 Apr-Jun;52(2):119–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CC, Kuo CC. Chronic cough: tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. CMAJ. 2010 Dec;182(18):E859. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurunathan U. Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: a rare cause of difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Jun;104(6):787–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Busaidi N, Dhuliya D, Habibullah Z. Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica: case report and literature review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012 Feb;12(1):109–12. doi: 10.12816/0003096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magro P, Garand G, Cattier B, Renjard L, Marquette CH, Diot P. Association of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica and ozene. Rev Mal Respir. 2007 Sep;24(7):883–7. doi: 10.1016/s0761-8425(07)91391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harma R, Suurkari S. Tracheopathia chondro- osteoplastica. A clinical study of thirty cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 1977 Jul-Aug;84(1–2):118–23. doi: 10.3109/00016487709123949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Virchow R. Die krankhaften Geschwülste. 1st ed. 1. Berlin: Hirschwald; 1863. pp. 442–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aschoff-Freiburg L. Ueber Tracheopathia Osteoplastica. Verh Dtsch Gesch Pathol. 1910;14:125–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen AY, Donovan DT. Impaired ciliary clearance from tracheopathia osteoplastica of the upper respiratory tract. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997 Dec;117(6):S102–104. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marom EM, Goodman PC, McAdams HP. Diffuse abnormalities of the trachea and main bronchi. AJR. 2001 Mar;176(3):713–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb EM, Elicker BM, Webb WR. Using CT to diagnose nonneoplastic tracheal abnormalities: appearance of the tracheal wall. AJR. 2000 May;174(5):1315–21. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prince JS, Duhamel DR, Levin DL, Harrell JH, Friedman PJ. Nonneoplastic lesions of the tracheobronchial wall: radiologic findings with bronchoscopic correlation. Radiographics. 2002 Oct;22:S215–30. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc02s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wever WD, Vandecaveye V, Lanciotti S, Verschakelen JA. Multidetector CT-generated virtual bronchoscopy: an illustrated review of the potential clinical indications. Eur Respir J. 2004 May;23(5):776–82. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00099804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]