Abstract

Objective

Personality traits are presumed to endure over time but the literature regarding older age is sparse. Furthermore, interpretation may be hampered by the presence of dementia-related personality changes. The aim was to study stability in neuroticism and extraversion in a population sample of women who were followed from mid to late life.

Method

A population-based sample of women born in 1918, 1922 or 1930 was examined with the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) in 1968–1969. EPI was assessed after 37 years in 2005–2006 (n=153). Data from an interim examination after 24 years were analysed for the subsample born in 1918 and 1922 (n=75). Women who developed dementia at follow-up exams were excluded from the analyses.

Results

Mean-levels of neuroticism and extraversion were stable at both follow-ups. Rank-order and linear correlations between baseline and 37-year follow-up were moderate ranging between 0.49–0.69. Individual changes were observed, and only 25% of the variance in personality traits in 2005–2006 could be explained by traits in 1968–1969.

Conclusion

Personality is stable at the population level but there is significant individual variability. These changes could not be attributed to dementia. Research is needed to examine determinants of these changes, as well as their clinical implications.

Keywords: Neuroticism, extraversion, Eysenck Personality Inventory, longitudinal, old age

Introduction

Personality traits are relatively enduring patterns of thinking, feeling and behaviour (1) that are commonly assessed with personality questionnaires in studies that examine the relationship between personality and health (2–8). The extent to which personality traits change over the life course is debated, however (9–12). Some studies report only minor changes in personality over time in adulthood (13–20). Despite the belief that “personality change is the exception rather than the rule after age 30” (21), substantial changes have been documented after age 30 (22, 23), and individual differences in the rate of change in neuroticism and extraversion have been reported (24, 25). Relatively high levels of trait stability were demonstrated among both men and women in a quantitative review of longitudinal personality studies, but trait consistency estimates were not high enough to warrant a conclusion that traits remain unchanged in adulthood (26). Most longitudinal studies on personality change have had follow-ups of less than ten years (1, 20, 26–28); many involve samples of college students.

The literature on the temporal stability of personality traits from mid-life to late-life is limited. In Ferguson’s meta-analysis (29), there were three studies with a baseline age range of 42 to 62 years and two studies with a baseline age of 63 to 83 years. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (30) followed men with the Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey over 42-years; women were followed over 24 years. Scales related to neuroticism showed curvilinear declines up to age 70. Thereafter, increases were observed. Increased neuroticism was also reported in four studies with shorter follow-up periods (19, 20, 24, 25).

Regarding extraversion, results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging showed stability over mid-life followed by decline in old age (31). In a 12-year follow-up (20), participants became less extroverted as they passed from later mid-life into old age.

Life events influence the stability of neuroticism (32–34) but no such relationship has been observed regarding extraversion (33). It is assumed that highly neurotic persons are more susceptible to the impact of life events due to their enhanced emotional reactivity (35) but a reciprocal causation between life events and neuroticism has been suggested (33).

The study of personality stability in late-life is complicated by the fact that dementia is common in older populations. Failure to take this diagnosis into account may limit interpretation of results from population studies, as neuroticism has been reported to be associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease (36, 37–39).

Aims of the study

The aim of this study is to investigate the stability of the personality traits neuroticism and extraversion in a representative population of women followed from mid-life in 1968 to late-life in 2005 (i.e., 37-years between assessments), and to examine possible influences on personality stability.

Material and methods

Study population

The study is part of the Prospective Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden (40, 41), which was initiated in 1968–1969. The examinations included neuropsychiatric and somatic assessments. Dementia diagnoses for participants in the neuropsychiatric examinations were based on combined information from the neuropsychiatric examinations and the close informant interview, as described in detail elsewhere (42). Dementia diagnosis, made in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (third edition, revised) (DSM-III-R) (43) was used for exclusion purposes only.

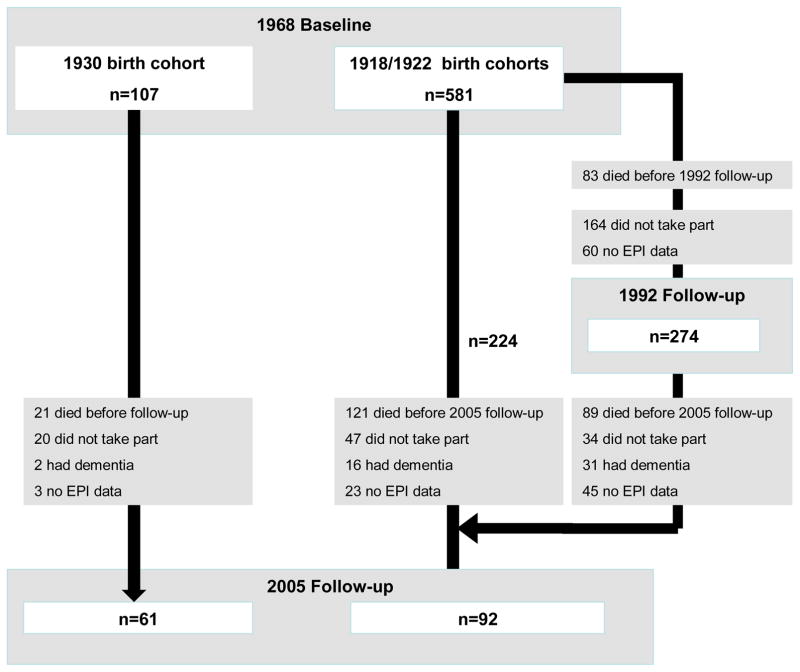

A sample comprising 710 women born in 1918, 1922 or 1930 underwent a comprehensive psychiatric examination in 1968 and 688 of these completed the self-report Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) (44). The women were re-examined in 2005–2006. Among those 688 who provided EPI data in 1968, 314 died before 2005 and 101 declined participation, leaving 273 subjects with both baseline and 37-year follow-up data. Forty-nine were excluded because of dementia and 71 due to missing values, leaving a total of 153 non-demented participants with data for both 1968 and 2005 (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Attrition and participation in Eysenck Personality Inventory at 1968 baseline and follow-ups in 1992 and 2005.

Figure 1 shows further that a subgroup (those born in 1918 and 1922) was also examined in 1992–1993. Out of 581 participating at baseline in 1968–1969, 83 had died and 164 declined participation or did not return the EPI questionnaire in 1992–1993. Sixty were excluded due to missing values. In all, 274 non-demented women were available for a 24-year follow-up analysis. Seventy-five women without dementia had EPI data at examinations in both 1992–1993 and 2005–2006, allowing a 13-year follow-up.

In this paper, we present the longitudinal results on the EPI for women born in 1918, 1922 or 1930 who participated in 1968–1969 and 2005–2006 (n=153), for the subgroup of women born in 1918 or 1922 who participated in 1968–1969 and in 1992–1993 (n=274), and for those who participated in all three study waves (n=75). Due to small sample sizes, groups born in 1918 and 1922 were merged in the analyses.

Measures

Eysenck Personality Inventory

The Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) is designed to measure the personality dimensions extraversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability, each with 24 items. Those with high neuroticism scores are described as showing emotional overreaction combined with low ego-strength, guilt proneness, anxiety and psychosomatic concerns. Persons with high extraversion scores are characterised as sociable, outgoing, impulsive and uninhibited (45). In a study of re-test reliability over a period of 30 days elderly, high reliability coefficients were found (extraversion=0.79, neuroticism =0.82) (46) Test–retest reliability coefficients for periods of 9 months to 1 year have been found to be 0.81 to 0.91 for Neuroticism and 0.82 to 0.97 for Extraversion (47).

Predictors of personality change

We considered a number of self-reported variables that might be associated with personality change, including childhood life stressors (being adopted, parents’ divorce, poor upbringing, problems at school, and experiencing the death of a parent in childhood), and baseline marital status (not ever married, married, divorced and widowed). A question about psychological distress was asked by a physician at the 1968 examination. The question was “Have you experienced any period (one month or longer) of stress/distress, i.e. feelings of irritability, tension, nervousness, fear, anxiety or sleep disturbances in relation to circumstances in everyday life, such as work, health, or family situation?” Responses were rated as follows: 0 = never experienced any period of distress, 1 = period of distress more than 5 years ago, 2 = one period of distress during the last 5 years, 3 = several periods of distress during the last 5 years, 4 = constant distress during the last year, or 5 =constant distress during the last 5 years. The responses were then categorised into the following groups: no distress (response 0–2) and frequent/constant distress (response 3–5).

Other life events variables, also obtained in the psychiatric examination, were depression (using a dichotomized global rating of depression) (48) in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (third edition) (DSM-III) on criteria (49) and a history of stroke. Variables obtained at follow-up in 2005 and used in the analyses of association included depressive symptoms, measured by The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (50), and cognitive functioning, measured by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (51).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Paired t-tests were used to compare mean levels of extraversion and neuroticism. Spearman rank order correlation coefficients were used to describe the relative position of individuals within the studied group. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to explore the strength of the relationship between continuous variables. Differences between proportions for categorical variables were analysed with Chi-squared tests. Fisher’s exact test was used to explore association between background factors and change in EPI. Statistical significance was determined using p < 0.05.

Individual change was defined as a raw score change of 5 points or more. The rationale behind this was that it corresponds to a change of individual score of at least 20 %, which we regarded as clinically meaningful. A change score of 5 or more corresponds to a difference greater than 1 SD (4.4 for neuroticism and 3.4 for extraversion in 1968–1969). For the tests of factors related to personality trait stability, the women were categorized in two groups: those whose neuroticism/extraversion scores remained within 4 points and those whose scores increased or decreased by more than 4 points.

Results

Mean-level personality change

Mean-levels of neuroticism and extraversion were not significantly different over the 37-year follow-up in the total group (Table 1). In fact, the mean scores for extraversion were nearly identical. However, there was a statistically significant increase in neuroticism in the 1918/1922 birth cohort both over the 37 year follow-up (Table 1), and over the final 13 years of the study (Table 1). In that birth cohort, there was an increase in extraversion from 1968 to 1992 (Table 1), but not over the subsequent 13 years. These patterns were not observed in the 1930 birth cohort.

Table 1.

Mean levels of neuroticism and extraversion in accordance with the Eysenck Personality Inventory at baseline and follow-up in the Prospective Population Study of Women in Gothenburg.

| N | Neuroticism | Extraversion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | Mean (sd) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 1968 | 2005 | Paired t-test and Cohen’s D | 1968 | 2005 | Paired t-test and Cohen’s D | ||

| All participants | 153 | 7.7 (4.4) | 8.2 (4.5) | t=−1.5, 152 df, p=.455 Cohen’s D −.12 |

11.5 (3.4) | 11.6 (3.4) | t=−.4, 152 df, p=.721 Cohen’s D −.03 |

| Birth cohort 1930 | |||||||

| Participants | 61 | 8.3 (4.6) | 8.3 (5.2) | t=−0.3, 60 df, p=.979 Cohen’s D −.003 |

11.7 (3.4) | 11.9 (3.7) | t=−0.5, 60 df, p=.623 Cohen’s D −.06 |

| Died before 2005 | 21 | 8.6 (4.4) | 11.2 (3.1) | ||||

| Surviving non-participant a | 25 | 5.8 (4.7) | 11.2 (2.6) | ||||

| Birth cohort 1918/1922 | |||||||

| Participants | 92 | 7.3 (4.0) | 8.2 (3.2) | t=−2.1, 91 df, p=.038 Cohen’s D −.22 |

11.4 (3.5) | 11.4 (3.2) | t=0.0, 91 df, p=1.000 Cohen’s D .00 |

| Died before 2005 | 293 | 8.3 (4.7) | 11.5 (3.1) | ||||

| Surviving non-participant a | 196 | 8.2 (4.4) | 11.3 (3.5) | ||||

| 1968 | 1992 | 1968 | 1992 | ||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Participants (24 yr follow-up) | 274 | 7.7 (4.2) | 7.9 (4.3) | t=−0.7, 273 df, p=.455 Cohen’s D −.04 |

10.9 (3.4) | 11.4 (3.6) | t=−3.0, 273 df, p=.003 Cohen’s D −.18 |

| 1992 | 2005 | 1992 | 2005 | ||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Participants (13 yr follow-up) | 75 | 6.9 (3.7) | 8.1 (3.2) | t=−3.5, 74 df, p=.001 Cohen’s D −.40 |

11.7 (3.8) | 11.1 (3.2) | t=1.9, 74 df, p=.057 Cohen’s D .22 |

Attrition due to incomplete EPI-questionnaire, dementia or refusal to participate.

Rank-order stability

For neuroticism, the rank-order coefficient (Table 2) over the 37-year follow-up (1968–2005) was close to moderate, in the total cohort 0.49 (0.52 in the 1930 birth cohort and 0.47 in the 1918/1922 birth cohort). The rank-order coefficient in the 24-year follow-up (1968–1992) was moderate, 0.59, and 0.67 in the 13-year follow-up (1992–2005).

Table 2.

Spearman rank-order correlations and Pearson correlations for neuroticism and extraversion in accordance with the Eysenck Personality Inventory at baseline and at follow-ups.

| Year span | 1968–2005 | 1968–1992 | 1992–2005 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Birth cohort | Birth cohort | Birth cohort | Birth cohort | ||||||

| N=153 | 1918/1922 n=92 | 1930 n=61 | 1918/1922 n=274 | 1918/1922 n=75 | ||||||

| (rho) | (r) | (rho) | (r) | (rho) | (r) | (rho) | (r) | (rho) | (r) | |

| Neuroticism | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.70 |

| Extraversion | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

(rho) – Spearman’s rank order correlation

(r) – Pearson correlation

All correlations significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

For extraversion, the rank-order coefficient over the 37-year follow-up was 0.58. The coefficient in the 1918/1922 birth cohorts was 0.66 and in the 1930 birth cohort 0.46. The rank-order coefficient for extraversion in the 24-year follow-up (1968–1992) was 0.61, and 0.69 in the 13-year follow-up (1992–2005).

Pearson linear correlations

The correlation between neuroticism score at baseline and 37-year follow-up was 0.50 (Table 3). Correlations were 0.5 between 1968 and 1992–1993, and 0.70 between 1992–1993 and 2005–06. Correlations between extraversion score at baseline and at 37- (0.57), 24- (0.63) and 13-years (0.68) were similar.

Table 3.

Individual change categorised by raw-score changes in neuroticism and extraversion in accordance with the Eysenck Personality Inventory in two cohorts of women.

| Study year comparison | Birth Cohort 1930 | Birth cohort 1918/1922 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Decreased ≥5 points | Stayed within +/− 4 points | Increased ≥ 5 points | Decreased ≥5 points | Stayed within +/− 4 points | Increased ≥ 5 points | Test1 | ||

| Neuroticism | 1968–2005 | 13 (21%) | 38 (62%) | 10 (16%) | 9 (10%) | 67 (73%) | 16 (17%) | 0.213 |

| 1968–1992 | - | - | - | 43 (16%) | 200 (73%) | 31 (11%) | ||

| 1992–2005 | - | - | - | 7 (9%) | 61 (81%) | 7 (9%) | ||

| Extraversion | 1968–2005 | 8 (13%) | 47(77%) | 6 (10%) | 5 (5%) | 80 (87%) | 7 (8%) | 0.127 |

| 1968–1992 | - | - | - | 26 (9%) | 224 (82%) | 24 (9%) | ||

| 1992–2005 | - | - | - | 12 (16%) | 62 (78%) | 1 (5%) | ||

P-values from Fisher’s exacts tests between those staying within +/− 4 points and other categories combined.

Individual change

Individual change (Table 3) was observed in 37% of the women in the neuroticism score in the 1930 birth cohort and in 27% of the women in the 1918/1922 birth cohort at 37-year follow-up. Proportions with changes were similar at the 24- and 13-year follow-ups. Regarding extraversion, 23% of the women in the 1930 birth cohort and 13% of those in the 1918/1922 birth cohort had changed 5 points or more at the 37-year follow-up.

Predictors of personality change

No relationship was found between any life stressors in childhood and change of either neuroticism or extraversion at any follow up with exception of participants who had experienced the death of a parent in childhood. A relationship was observed between mother’s death during childhood and stable neuroticism score (χ2=4.31, p<0.05). Those cases who had experienced the loss of their mother were more likely to have a stable neuroticism score between 1968 and 1992. A similar but not significant result was seen for those who had experienced the death of their father having more stable neuroticism scores from 1968 to 2005 (χ2=3.70, p=.064) than whose who had not. While we could show no association between stress at baseline and EPI change in 2005, there was a tendency for those reporting stress in 1968 to be less likely to have a stable neuroticism score at the interim follow-up in 1992 (χ2=3.81, p=.057).

A diagnosis of depression in accordance with DSM-III in 1968 was associated with neither change in neuroticism nor change in extraversion over the 37 year follow-up period. However, associations between baseline depression and changes in neuroticism (χ2=5.10, p=.035) and in extraversion (χ2=4.17, p=.042) were observed over the 24 year follow-up for women who took part in the interim examination in 1992.

Marital status in 1968 was found to be associated with neuroticism in 1992. Those who had never married in 1968 had a greater stability in neuroticism in 1992. No association between marital status and change in neuroticism score was found at follow-up in 2005. The same was the case regarding change in extraversion score. No relationships could be shown regarding history of stroke and changes in neuroticism/ extraversion at either follow-up (results not shown).

Neither depressive symptom burden, measured by MADRS, or cognitive functioning, measured by MMSE differed in women with and without stable neuroticism/extraversion scores.(results not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the longest follow-up examining changes in neuroticism and extraversion from mid-life to old age in a general population sample of women. We found that mean levels of extraversion and neuroticism were moderately stable between mid-life and late-life in these women who were followed for 37 years. Our findings contrast with a recent report of declining mean levels of extraversion (52). Mean level changes accelerated with age in that study, which had a testing interval of six years.

Rank-order and linear correlations between 1968 and 2005 were moderate, ranging between 0.49–0.69. A consistent finding is that rank-order stability increases with age (26, 29). In Roberts’s meta-analysis (26), stability coefficients were lower in younger cohorts (late 20s) than slightly older cohorts (late 50s). This is partly supported in our sample. There was no difference in rank order stability between birth cohorts regarding neuroticism but the birth cohort born in 1930 (38 years of age at baseline) had a lower rank order coefficient in extraversion follow up compared to the birth cohort born in 1918/1922 (50–54 years of age at baseline). In a recent longitudinal study by Wortman and colleagues (53), stability in personality was highest between 50 and 70 years of age, and thereafter extraversion and neuroticism declined. This is also supported in a longitudinal study by Lucas and Donnellan (54) who found that rank-order stability peaked in adulthood and decreased with advancing age (past about age 60).

Substantial intra-individual changes were observed in one third of the sample. Neuroticism scores either increased or decreased in slightly less than one third of women in our study over the 37 years. Intra-individual change in neuroticism was particularly pronounced in the later born cohort (aged 38 in 1968). Similar results have been reported in men, initially aged 43–91 and followed over 12 years (24). Extraversion scores changed in less than one fifth over the 37 years. Other studies have shown substantial portions of individual variation in extraversion (24, 55). One reason for variation might be that different facets of extraversion have distinct and different patterns. In a longitudinal German study of personality across the adulthood using an extraversion scale focusing on social vitality, a strong effect for age was found. Older people tended to show a stronger decrease in extraversion than younger people in a four year period (56). Social dominance, another facet of extraversion, has been found to increase with age (26).

For the subgroup born 1918 and 1922 that had 3 examination points, an increase in neuroticism was observed in both the 37-year follow-up (between 1968–2005) and the 13-year follow-up (between 1992–2005). While our study included women only, our results parallel those reported for men in the 42 year follow-up conducted by Terracciano and collegues (30). Taken together, findings suggest an increase in neuroticism in later life. This might be explained by age-related brain changes, other health problems, or the accumulation of different changes in life such as decline in activity and functionality with increasing age (57, 58).

Longer follow-up time yielded lower stability in our study, as previously reported by Roberts and DelVecchio (26). Our results might be explained by the longer interval and the relatively older age of our cohorts. Findings also suggest considerable individual change of personality in women from mid-life to old age. The stability coefficients in our study are more consistent with the observation of Ardelt (59) that uncorrected stability coefficients for retest intervals of 20 years or more are rarely greater than 0.50.

In the analysis of association between predictors and change in personality, no factor was found to be was associated with neuroticism/extraversion change at the 37 year follow-up. However, depression, marital status and death of mother in childhood, all factors obtained at baseline in 1968, were found to be associated personality trait change in 1992. These findings raise several questions. Perhaps our inability to show associations at the 2005 follow-up is related to the small size of this survival sample. Alternatively, change in “later” late life may be less related to early and mid-life factors than changes in “early” late life. Scollon and Diener (55) followed extraversion and neuroticism over time in persons aged 16–70, reporting significant individual differences in for both traits associated with work and relationship satisfaction, and findings were independent of age. Further research is needed to identify determinants of changes in neuroticism and extraversion over long periods of time into extreme old age.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the long follow-up, comprising almost four decades, the representative population-based sample, including both community-dwelling and institutionalised individuals, the use of a validated personality instrument, and the rigorous diagnosis of dementia ensuring that findings are not confounded by dementia-related personality change.

There are a number of limitations. First, cumulative attrition is a problem in all long-term follow-up studies, and only 153 out of 668 who completed the examination in 1968–1969 did so in 2005–2006. Most of those who did not participate in 2005 had died during follow-up or were excluded because of dementia. Participation bias has been pointed out as potentially problematic in the long-term study of personality into late-life (37). While women who participated in 2005–2006 were probably healthier than those who did not (41), we take note of the fact that baseline neuroticism and extraversion scores did not differ between participants and non-participants in the 37-year follow-up. Second, the decision to define individual change as 5 or more points could be debated. Reliable Change Index is often used to measure intra-individual change (60). The extremely long period of follow-up renders this method less appropriate. Therefore, we defined a clinically relevant change criterion, similar to what was done in another recent study (19). The decision to define individual change as 5 points or more was based on the fact that this amount of change means that a different response was given in at least 20% of the items at follow-up. We considered using a change score that corresponded to 2 SD, but the groups would have been too small for meaningful analyses and the personality changes would have been greater than expected under normative conditions. Third, findings may reflect both ageing-related changes and cohort differences. Another study design would be necessary to weed out these different effects. Fourth, results cannot be generalised to men. The original study was designed specifically to examine the epidemiology of women’s health in mid-life, a rare researched topic at the time of the study initiation in 1968. Fifth, despite an exhaustive review we were able to identify only one study that reported test-retest-reliability in a sample of middle aged or older people; consequently, there is no firm normative benchmark against which our findings can be interpreted. Nonetheless, our findings generally correspond to those observed in studies that have used other personality instruments over periods of two decades or more.

Conclusion

Neuroticism and extraversion were stable at the population level in women followed over 37 years from mid-life to late-life. One third of the sample showed considerable intra-individual variation indicating moderate stability in these personality traits from mid-life to old age. Research is needed to examine determinants of these changes, as well as their clinical implications.

Significant outcomes.

Mean levels of extraversion and neuroticism were relatively stable between mid-life and late-life in this population sample of women followed for 37 years.

Rank order consistency was moderate in neuroticism and extraversion from mid-life to old age.

Substantial intra-individual changes were observed in one third of the sample.

Limitations.

This is a survival sample; woman who survived and participated at follow-up were healthier than those who did not.

Findings may reflect both ageing-related changes and cohort differences.

All participants were women and results cannot be generalised to men.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (11267, 2005-8460, 825-2007-7462), the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (no 2001-2835, 2001-2646, 2003-0234, 2004-0150, 2006-0020, 2008-1229, 2004-0145, 2006-0596, 2008-1111, EpiLife, WISH) and from the United States National Institutes of Health K24MH072712.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None

References

- 1.Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce P, Parker G, Barnett B, Cooney M, Smith F. Personality as a vulnerability factor to depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:106–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson D. Dimensions underlying the anxiety disorders: a hierarchical perspective. Current opinion in psychiatry. 1999;12:181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilhelm K, Parker G, Dewhurst-Savellis J, Asghari A. Psychological predictors of single and recurrent major depressive episodes. J Affect Disord. 1999;54:139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Os J, Jones PB. Neuroticism as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1129–34. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shipley BA, Weiss A, Der G, Taylor MD, Deary IJ. Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: a 21-year prospective cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:923–31. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815abf83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duberstein PR, Palsson SP, Waern M, Skoog I. Personality and risk for depression in a birth cohort of 70-year-olds followed for 15 years. Psychol Med. 2008;38:663–71. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm K, Parker G, Geerligs L, Wedgwood L. Women and depression: a 30 year learning curve. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:3–12. doi: 10.1080/00048670701732665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraley RC, Roberts BW. Patterns of continuity: a dynamic model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychol Rev. 2005;112:60–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Age changes in personality and their origins: comment on Roberts, Walton, and Viechtbauer (2006) Psychol Bull. 2006;132:26–8. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Personality traits change in adulthood: reply to Costa and McCrae (2006) Psychol Bull. 2006;132:29–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashton MC. Individual differences and personality. London: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson LV. Personality changes in the aged. A transectional and longitudinal study with the Eysenck Personality Inventory. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;68:202–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb06999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haan N, Millsap R, Hartka E. As time goes by: change and stability in personality over fifty years. Psychol Aging. 1986;1:220–32. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn SE. Stability of personality self-ratings over 30 years: evidence for an age/cohort interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:813–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Personality in adulthood: a six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:853–63. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viken RJ, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. A developmental genetic analysis of adult personality: extraversion and neuroticism from 18 to 59 years of age. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66:722–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae R. Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In: Heatherton T, Weinberger J, editors. Can Personality change? Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steunenberg B, Twisk JW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Kerkhof AJ. Stability and change of neuroticism in aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P27–33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.p27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allemand M, Zimprich D, Martin M. Long-term correlated change in personality traits in old age. Psychol Aging. 2008;23:545–57. doi: 10.1037/a0013239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacCrae R, Costa PT., Jr . Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field D, Millsap RE. Personality in advanced old age: continuity or change? J Gerontol. 199;46:P299–308. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.p299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helson R, Wink P. Personality change in women from the early 40s to the early 50s. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:46–55. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mroczek DK, Spiro A., 3rd Modeling intraindividual change in personality traits: findings from the normative aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:P153–65. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.p153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Small BJ, Hertzog C, Hultsch DF, Dixon RA. Stability and change in adult personality over 6 years: findings from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:P166–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.p166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: a quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rantanen J, Metsapelto RL, Feldt T, Pulkkinen L, Kokko K. Long-term stability in the Big Five personality traits in adulthood. Scand J Psychol. 2007;48:511–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleidorn W, Kandler C, Riemann R, Spinath FM, Angleitner A. Patterns and sources of adult personality development: growth curve analyses of the NEO PI-R scales in a longitudinal twin study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97:142–55. doi: 10.1037/a0015434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson CJ. A meta-analysis of normal and disordered personality across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:659–67. doi: 10.1037/a0018770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Longitudinal trajectories in Guilford-Zimmerman temperament survey data: results from the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:P108–16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Brant LJ, Costa PT., Jr Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:493–506. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The kids are alright: growth and stability in personality development from adolescence to adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:670–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middeldorp CM, Cath DC, Beem AL, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI. Life events, anxious depression and personality: a prospective and genetic study. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1557–65. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lockenhoff CE, Terracciano A, Patriciu NS, Eaton WW, Costa PT., Jr Self-reported extremely adverse life events and longitudinal changes in five-factor model personality traits in an urban sample. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:53–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM, Hovens JG, Roelofs K, van Oppen P, Zitman FG, et al. Positive and negative life events and personality traits in predicting course of depression and anxiety. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:462–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duberstein PR, Chapman BP, Tindle HA, Sink KM, Bamonti P, Robbins J, Jerant AF, Franks P. Personality and risk for Alzheimer’s disease in adults 72 years of age and older: a 6-year follow-up. Psychol Aging. 2011;26:351–62. doi: 10.1037/a0021377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson RS, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Mendes de Leon CF, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Proneness to psychological distress is associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2003;61:1479–85. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000096167.56734.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Li Y, Bienias JL, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Proneness to psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer disease in a biracial community. Neurology. 2005;64:380–2. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149525.53525.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duchek JM, Balota DA, Storandt M, Larsen R. The power of personality in discriminating between healthy aging and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:P353–61. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bengtsson C, Ahlqwist M, Andersson K, Bjorkelund C, Lissner L, Soderstrom M. The Prospective Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden, 1968–69 to 1992–93. A 24-year follow-up study with special reference to participation, representativeness, and mortality. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15:214–9. doi: 10.3109/02813439709035031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lissner L, Skoog I, Andersson K, Beckman N, Sundh V, Waern M, et al. Participation bias in longitudinal studies: experience from the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21:242–7. doi: 10.1080/02813430310003309-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skoog I, Nilsson L, Palmertz B, Andreasson LA, Svanborg A. A population-based study of dementia in 85-year-olds. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:153–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washinton DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eysenck H, Eysenck S. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. London: University of London Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eysenck H, Eysenck S. Manual of the Eysenck Personalty Questionnaire. London: Hodder & Stoughton Educational; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold D, Andres D. Personality test reliability: correlates for older subjects. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:530–2. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4905_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual for the Eysenck Personality Inevntory. San Diego, Calif: Educational & Industrial Testing Service; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hällström T. Point prevalence of major depressive disorder in a Swedish urban female population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1984;69:52–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968. (DSM-II) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mottus R, Johnson W, Deary IJ. Personality traits in old age: measurement and rank-order stability and some mean-level change. Psychol Aging. 2012;27:243–9. doi: 10.1037/a0023690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wortman J, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Stability and Change in the Big Five Personality Domains: Evidence From a Longitudinal Study of Australians. Psychol Aging. 2012 Jul 9; doi: 10.1037/a0029322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Personality development across the life span: longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:847–61. doi: 10.1037/a0024298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scollon CN, Diener E. Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91:1152–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Specht J, Egloff B, Schmukle SC. Stability and change of personality across the life course: the impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:862–82. doi: 10.1037/a0024950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Mapping changes in the human cortex throughout the span of life. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:372–92. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schrack JA, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. The energetic pathway to mobility loss: an emerging new framework for longitudinal studies on aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58 (Suppl 2):S329–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ardelt M. Still stable after all these years? Personality stability theory revised. Soc Psychol Quarterly. 2000;63:392–405. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacobsen NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]