Abstract

Background

Celiac disease (CD) is under-diagnosed in the United States, and factors related to the performance of endoscopy may be contributory.

Aims

to identify newly diagnosed patients with CD who had undergone a prior esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and examine factors contributing to the missed diagnosis.

Methods

We identified all patients age ≥18 years whose diagnosis of CD was made by endoscopy with biopsy at our institution (n=316), and searched the medical record for a prior EGD. We compared those patients with a prior EGD to those with without a prior EGD with regard to age at diagnosis and gender, and enumerated the indications for EGD.

Results

Of the 316 patients diagnosed by EGD with biopsy at our center, 17 (5%) had previously undergone EGD. During the prior non-diagnostic EGD, a duodenal biopsy was not performed in 59% of the patients, and ≥4 specimens (the recommended number) were submitted in only 29% of the patients. On the diagnostic EGD, ≥4 specimens were submitted in 94%. The mean age of diagnosis of those with missed/incident CD was 53.1 years, slightly older than those diagnosed with CD on their first EGD (46.8 years, p=0.11). Both groups were predominantly female (missed/incident CD: 65% vs. 66%, p=0.94).

Conclusions

Among 17 CD patients who had previously undergone a non-diagnostic EGD, nonperformance of duodenal biopsy during the prior EGD was the dominant feature. Routine performance of duodenal biopsy during EGD for the indications of dyspepsia and reflux may improve CD diagnosis rates.

Keywords: Celiac Disease, Endoscopy, Biopsy, Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of Celiac Disease (CD) has increased four-fold in recent decades in the United States, but the vast majority of patients with CD remain undiagnosed.1,2 Seroprevalence studies have consistently shown that 0.8 to 0.9% of the population has CD, but in the United States, the proportions of patients who were undiagnosed were 95% in Olmsted County,2 90% in Wyoming,3 89% in Maryland,4 and 83% among participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 5

Multiple factors likely contribute to the low CD diagnosis rates in the US. There are several potential steps in the diagnostic process during which patients can be missed, including patient factors, the case finder,6 or pathology interpretation errors.7 Issues relating to the performance of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and biopsy also appear to play a role. A recent analysis of the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative National Endoscopy Database found that among patients undergoing EGD for iron deficiency, anemia, diarrhea, or weight loss, only 43% had a small bowel biopsy during this procedure.8 These rates increased each year, but even in 2009, the most recent year in that study, only 51% had a biopsy.

When small bowel biopsy is performed, the number of specimens may not be adequate. Guidelines recommend that 4 or more specimens be submitted, but in a study of a national pathology database, the most common number of specimens submitted during EGD was 2.9 Only 35% of patients had 4 or more specimens submitted, despite a doubling of the diagnostic yield for CD when physicians adhered to these guidelines.

Thus it remains possible that some patients with CD undergo EGD and that after the procedure they remain undiagnosed. We aimed to determine how frequently this occurs, by identifying newly diagnosed CD patients who had undergone a prior EGD. Such patients either had “missed” CD or “incident” CD. We also aimed to identify factors contributing to a possibly missed diagnosis of CD during EGD.

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional study at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, a referral center that specializes in the diagnosis and management of CD. This cross-sectional study was an analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients with biopsy-proven CD. In this study we included only those patients whose diagnosis of CD was made by EGD and biopsy performed at our center. This includes patients who were referred from within our medical center, or patients referred from other institutions for positive serologies or a clinical suspicion of CD. Restricting this analysis to internally diagnosed patients allowed us to maximize our ability to detect, via querying the electronic medical record (which reaches back to January 1, 1990), whether these patients had additional EGD’s prior to being diagnosed with CD. The CD patient database consists of patients seen by one physician (PHRG) since 1990, or by other practitioners since the establishment of the Celiac Disease Center in 2001; all patients in the database prior to July 1, 2011 were assessed for prior endoscopy.

The primary outcome of interest was the performance of a prior EGD at our institution before being diagnosed with CD. For these patients we collected their age, gender, mode of presentation, and clinical indication for the EGD, both the diagnostic and the prior non-diagnostic procedure.

Histopathologic Review

A subset of patients with missed/incident CD had undergone not only EGD, but also a duodenal biopsy during that non-diagnostic procedure. These patients were identified and all prior duodenal biopsies were reviewed by a pathologist (GB) with expertise in the diagnosis of CD. This review of prior histology was compared to the initial histologic interpretation.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportion of patients with CD diagnosed at our medical center that had undergone a previous EGD, and we compared those with a previous EGD to those CD patients who did not have a previous EGD, with regard to their age, gender, and mode of presentation. For continuous variables we used the Mann-Whitney test, and for categorical variables we used the Chi Square and Fisher Exact Test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). The database used for this analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

RESULTS

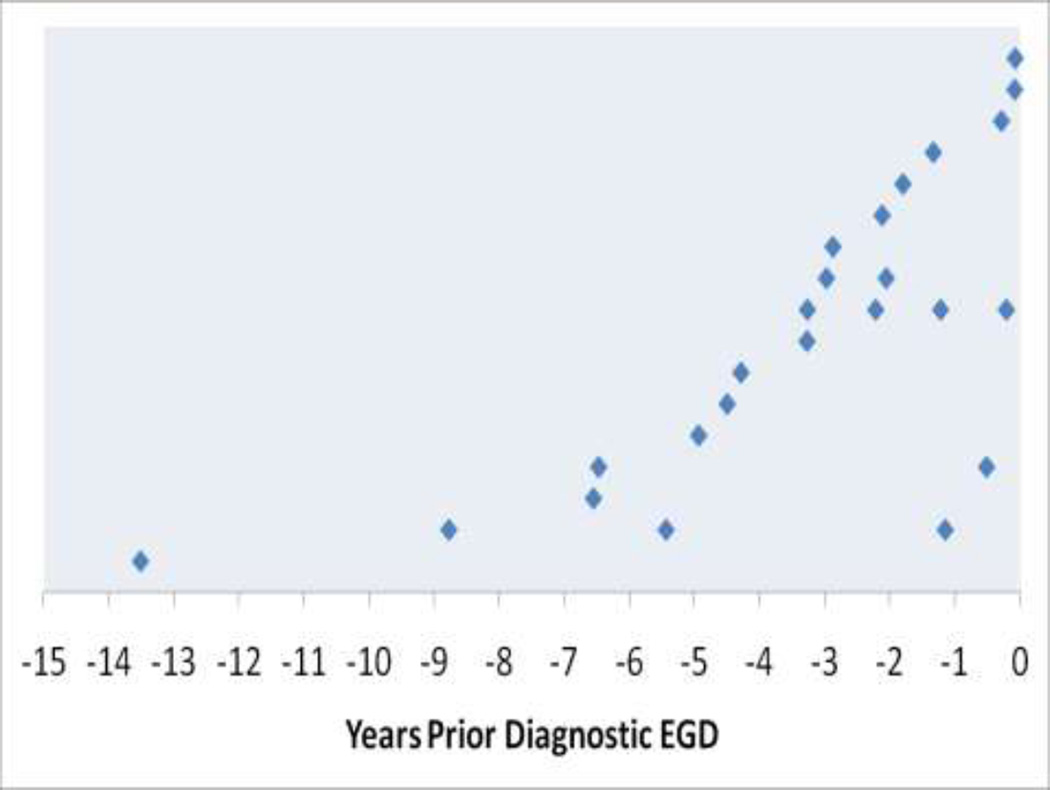

Of 1,095 patients with biopsy-proven CD, 316 (29%) had their diagnosis made by EGD with biopsy performed at our medical center. The remaining patients were referred after their diagnostic biopsy. Of these 316 patients diagnosed by EGD with biopsy at our medical center, 17 (5%) had undergone a previous endoscopy. Ten of those 17 (59%) had undergone the procedure by the same endoscopist, and 7 (41%) had undergone the procedure by a different endoscopist. Most (13/17, 76%) had one previous EGD, while four patients had more than one previous EGD, including one patient who had four EGD’s prior to the procedure at which CD was diagnosed (See Figure).

FIGURE.

Timing of previous (non-diagnostic) EGD’s in 17 patients who were ultimately diagnosed with CD. Each row represents a single patient, diagnosed at time 0.

Characteristics of the patients with missed/incident CD are listed in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis of those with missed (or incident) CD was slightly older than the age of diagnosis for the remainder of the CD patients. The nearly two thirds female predominance was similar in both groups. Those with missed/incident CD were more likely to have diarrhea, and were less likely to be asymptomatic or screen-detected.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with missed/incident CD

| Missed/Incident CD (n=17) |

Other CD patients (n=299) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (mean, years) | 53.1 | 46.8 | 0.19 |

| Gender | 0.94 | ||

| Male | 6 (35) | 103 (34) | |

| Female | 11 (65) | 196 (66) | |

| Mode of Presentation | 0.06 | ||

| Classical | 10 (59) | 88 (29) | |

| Non-Classical | 6 (35) | 158 (53) | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (6) | 53 (18) | |

The time elapsed between non-diagnostic and diagnostic endoscopy was highly variable. Three patients had a prior endoscopy within one year prior to diagnosis. Another 10 had an EGD between one and five years prior to diagnosis, and another four patients had EGD’s more remotely than five years prior to CD diagnosis. When accounting for multiple prior EGD’s, five of the 17 patients had an EGD within one year prior to their diagnosis of CD (see Figure).

The most common indication for the non-diagnostic endoscopy was dyspepsia or abdominal pain, followed by gastroesophageal reflux disease (Table 2). For the diagnostic EGD, diarrhea and work-up of positive CD serologies predominated. Among the 4 patients who had multiple previous EGD’s, dyspepsia was a prominent indication. One patient had gastric lymphoma and was undergoing surveillance, but duodenal biopsies were not done until CD serologies were checked. Esophageal problems such as dysphagia and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus likewise prompted multiple EGD’s prior to the development of symptoms suggestive of CD.

Table 2.

Non-diagnostic and diagnostic EGD’s in patients with missed/incident CD.

| Non-Diagnostic EGD | Diagnostic EGD | |

|---|---|---|

| Indication (%) | ||

| Dyspepsia/Abdominal pain | 5 (29) | 3 (18) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (12) | 6 (36) |

| Dysphagia | 2 (12) | 2 (12) |

| GERD/Barrett’s esophagus | 4 (24) | 1 (6) |

| Positive CD serologies | 0 | 5 (29) |

| Other | 4 (24) | 0 |

| Serologies | ||

| Any CD serologies checked | 3 (18) | 10 (59) |

| Any positive serologies | 2 (12) | 6 (35) |

| Endoscopic appearance of the duodenum | ||

| Normal | 11(65) | 8 (47) |

| Abnormal | 6 (35) | 9 (53) |

| Number of duodenal specimens submitted | ||

| No duodenal biopsy performed | 10 (59) | 0 |

| 1 | 2 (12) | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (6) |

| ≥4 | 5 (29) | 16 (94) |

Seropositivity rates are shown in Table 2. The majority (10/17, 59%) had serologies checked prior to the diagnostic EGD, and the serologies were positive in 60% (6/10). Of note, the majority of patients 10/17 (59%) were diagnosed with CD prior to 2001, when anti-gliadin antibodies were the most commonly employed CD antibodies. Only 3 of the 17 patients (18%) had serologies checked prior to the non-diagnostic EGD, and 2 had a positive serology. Of these three patients who had serologies checked prior to the non-diagnostic EGD, all were checked for anti-gliadin antibodies only; of the 10 patients who had any serological testing, 4 (40%) had exclusively anti-gliadin antibody testing.

The duodenum was noted to have an abnormal endoscopic appearance in 35% of the non-diagnostic EGD’s, and this was higher during the diagnostic EGD’s, 53% (Table 2). During the non-diagnostic endoscopy, the most common number of specimens submitted was zero (59%). Only 5 of the 17 patients (29%) had 4 or more specimens submitted. In contrast, 16 of 17 patients (94%) had 4 or more specimens submitted during the diagnostic EGD.

Among the seven patients who had a duodenal biopsy during the non-diagnostic EGD, the original histopathology findings ranged from normal to non-specific duodenal inflammation (Table 3). All of those patients who had a non-diagnostic duodenal biopsy had Marsh 3A, or partial villous atrophy, on subsequent EGD. On retrospective histopathology review of the prior non-diagnostic duodenal biopsies (after the diagnosis of CD was made), biopsies from 2 of the 7 patients exhibited findings consistent with Marsh 3A, while the rest were architecturally normal. Of note, however, 2 of the 5 “normal” biopsies showed focal increase and clustering of IELs at the villous tips. This pattern can be seen individuals with potential or latent CD, but is often overlooked by non-specialist pathologists. The diagnostic biopsy of those who had no prior duodenal biopsy had a more varied and advanced Marsh class at diagnosis; 4 out 10 had subtotal or total villous atrophy (Marsh 3B-3C)

Table 3.

Histopathologic features of non-diagnostic and diagnostic duodenal biopsies.

| Patient | Non-diagnostic EGD Original Histopathology |

Non-diagnostic EGD Histopathology Re-review |

Diagnostic EGD |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Focal mild inflammation/normal villi | Normal | Marsh 3A |

| B | Focal IEL, normal villi | Marsh 3A | Marsh 3A |

| C | Unremarkable | Normal* | Marsh 3A |

| D | Within normal limits | Normal | Marsh 3A |

| E | Mildly chronically inflamed | Normal | Marsh 3A |

| F | Histologically unremarkable | Normal* | Marsh 3A |

| G | Mildly inflamed | Marsh 3A | Marsh 3A |

Villous tip clustering of intraepithelial lymphocytes was evident despite normal villous architecture and absence of significant lamina propria inflammation. This pattern has been described in individuals with latent celiac disease.

DISCUSSION

We describe 17 patients whose diagnosis of CD was made after more than one EGD; in four of these patients, two or more EGD’s were performed prior to the diagnosis of CD. The demographics of these patients resembled those of other CD patients diagnosed at our institution with regard to their female predominance and mean age of diagnosis. However, they were less likely to be asymptomatic or screen-detected, which is expected, since these are patients who have already sought gastrointestinal care and underwent previous EGD.

Between 83% and 95% of patients with CD in the United States are undiagnosed.2–5 The proportion of undiagnosed patients is higher than European countries such Italy10 and Finland, where more than half of CD patients are diagnosed.11 This low rate of diagnosis observed in the United States seems counterintuitive. One might have expected that the reputation in American health care for over-testing and over-diagnosis12 would lead to more CD diagnoses, since the threshold to test patients might be lower. But these data show that it is possible for CD patients to undergo multiple encounters with healthcare providers, including gastroenterologists, and undergo invasive testing including endoscopy and biopsy, while still eluding a CD diagnosis. Our observations are not unexpected because previous studies of large national databases have shown that patients undergoing EGD with symptoms compatible with CD often do not undergo duodenal biopsy,8 and that the majority of patients who have a duodenal biopsy do not have the recommended number of specimens submitted.9

Most of these patients with missed/incident CD had a clinical indication for dyspepsia or esophageal reflux during their prior EGD. These are the most common indications for EGD,13 and the question of whether duodenal biopsies should be done routinely in these settings is controversial. While some have advocated routine duodenal biopsies during all EGD’s based on the protean manifestations of CD,14 there are no published guidelines regarding the advisability of this practice. A meta-analysis of 10 studies found that histologic evidence of CD is present in 1% of patients undergoing EGD for dyspepsia,15 a prevalence similar to that of the general population. A similar uncertainty prevails with regard to the endoscopic evaluation of esophageal reflux. One study of patients with esophageal reflux found no increased prevalence of CD.16 But esophageal reflux is more common in CD patients than in the general population,17 and reflux symptoms often improve on a gluten-free diet after CD diagnosis.17 During endoscopic evaluation of reflux, which typically consists of an assessment for gross or microscopic evidence of esophagitis, one might consider concomitant duodenal biopsy as a rational practice since reflux symptoms can be a manifestation of CD.18 While a cost effectiveness analysis for serologic screening for CD in the general population has been performed,19 to date there are no published cost effectiveness studies regarding the performance of duodenal biopsy during EGD. Stratifying by serologic status or endoscopic appearance may not be the optimal approach, since many patients with CD have a duodenum with a normal endoscopic appearance20 and the sensitivity of serologies is imperfect.21

Most of the patients with missed/incident CD in this study did not have a duodenal biopsy performed. Review of the cases where EGD and duodenal biopsy had been performed prior to the diagnostic EGD, suggests that some cases might lack prior diagnostic histopathologic features and hence represent incident CD. However, review of small bowel biopsies by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist, familiar with histopathologic manifestations of CD, could help in earlier diagnosis of CD in a subset of cases.

Limitations of this study include its setting in a referral center, raising uncertainty regarding the generalizability of our findings. Its retrospective nature was necessary by design. But given the fact that many patients may have undergone non-diagnostic endoscopy elsewhere, we limited this analysis to those patients whose diagnosis was made by biopsy at our center. Nevertheless, it remains possible that other patients in this study may have undergone non-diagnostic EGD outside of this institution; thus the prevalence of missed/incident CD may be significantly higher.

Information regarding serological status was incomplete, since the majority of patients did not have serologies checked prior to the non-diagnostic EGD, and 41% did not have serological tests prior to the diagnostic biopsy. This is reflective of the variable performance of serologies in clinical practice, which may parallel the variable performance of small intestinal biopsy during endoscopy. 8,22 Most of these patients were diagnosed with CD prior to the availability of serologies with high sensitivities and specificities. In fact, all 3 patients who had serologies sent prior to the non-diagnostic EGD only had only anti-gliadin antibodies sent. The studies sent prior to the diagnostic EGD included newer serologies, and the positivity rate is higher, though still not as high as commonly reported,21 possibly due to the lower sensitivity of serologies in the setting of lesser degrees of villous atrophy.23 Lack of serological data, while a limitation, may reflect clinical practice where CD may be diagnosed in the context of direct referrals for EGD, such as an “open access” system.24

Since most patients with a prior endoscopy did not have prior duodenal biopsy, we do not know if these patients had missed CD, or developed CD between their two or more EGD’s. Additionally, we were not able to quantify the degree of morbidity during the period between non-diagnostic and diagnostic EGD’s. It would be important to quantify the consequences of missed CD.

In conclusion, 5% of patients diagnosed with CD at our institution had undergone a previous EGD; most did not have duodenal biopsies performed during the non-diagnostic EGD. Those who did undergo biopsy had non-specific findings, with all eventually being diagnosed with Marsh 3A lesions (partial villous atrophy). Dyspepsia and esophageal reflux were prominent symptoms among those undergoing non-diagnostic endoscopy. At present, there are no published guidelines regarding the routine performance of duodenal biopsy during EGD, and data regarding the cost effectiveness of this practice are lacking. Our study suggests that duodenal biopsies should be performed during endoscopy for dyspepsia and esophageal reflux. Such a practice may significantly increase the low CD diagnosis rates in the United States. Future studies are warranted to measure the impact of missed CD on morbidity among symptomatic patients seeking health care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: BL: The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (KL2 TR000081)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:88–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray JA, Van Dyke C, Plevak MF, Dierkhising RA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American community, 1950–2001. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:19–27. doi: 10.1053/jcgh.2003.50004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz KD, Rashtak S, Lahr BD, et al. Screening for celiac disease in a North American population: sequential serology and gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1333–1339. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catassi C, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, et al. Natural history of celiac disease autoimmunity in a USA cohort followed since 1974. Ann Med. 2010;42:530–538. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.514285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The Prevalence of Celiac Disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1538–1544. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, et al. Detection of Celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1454–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arguelles-Grande C, Tennyson CA, Lewis SK, Green PH, Bhagat G. Variability in small bowel histopathology reporting between different pathology practice settings: impact on the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:242–247. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebwohl B, Tennyson CA, Holub JL, Lieberman DA, Neugut AI, Green PH. Sex and racial disparities in duodenal biopsy to evaluate for celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebwohl B, Kapel RC, Neugut AI, Green PH, Genta RM. Adherence to biopsy guidelines increases celiac disease diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catassi C, Fabiani E, Ratsch IM, et al. The coeliac iceberg in Italy. A multicentre antigliadin antibodies screening for coeliac disease in school-age subjects. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1996;412:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virta LJ, Kaukinen K, Collin P. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed coeliac disease in Finland: results of effective case finding in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:933–938. doi: 10.1080/00365520903030795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ES, Welch HG. Could more health care lead to worse health? Hosp Pract (Minneap) 1999;34:15–16. 21–22. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1999.11443939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieberman D, Fennerty MB, Morris CD, Holub J, Eisen G, Sonnenberg A. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with dyspepsia: results from the national endoscopic data repository. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1067–1075. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green PH, Murray JA. Routine duodenal biopsies to exclude celiac disease? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:92–95. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)70072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford AC, Ching E, Moayyedi P. Meta-analysis: yield of diagnostic tests for coeliac disease in dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:28–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collin P, Mustalahti K, Kyronpalo S, Rasmussen M, Pehkonen E, Kaukinen K. Should we screen reflux oesophagitis patients for coeliac disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:917–920. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200409000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nachman F, Vazquez H, Gonzalez A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in patients with celiac disease and the effects of a gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leffler DA, Kelly CP. Celiac disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease: yet another presentation for a clinical chameleon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:192–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershcovici T, Leshno M, Goldin E, Shamir R, Israeli E. Cost effectiveness of mass screening for coeliac disease is determined by time-delay to diagnosis and quality of life on a gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:901–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickey W, Hughes D. Disappointing sensitivity of endoscopic markers for villous atrophy in a high-risk population: implications for celiac disease diagnosis during routine endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2126–2128. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leffler DA, Schuppan D. Update on serologic testing in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2520–2524. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harewood GC, Holub JL, Lieberman DA. Variation in small bowel biopsy performance among diverse endoscopy settings: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1790–1794. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams JA, Diamond B, Rotterdam H, Green PH. Seronegative celiac disease: increased prevalence with lesser degrees of villous atrophy. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:546–550. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000026296.02308.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giangreco E, D'Agate C, Barbera C, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in adult patients with refractory functional dyspepsia: value of routine duodenal biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6948–6953. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]