Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the prevalence of retinopathy in 517 youth with type 2 diabetes of 2–8 years duration enrolled in the TODAY study.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Retinal photographs were graded centrally for retinopathy using established standards.

RESULTS

Retinopathy was identified in 13.7% of subjects. Prevalence increased with age, diabetes duration, and mean HbA1c. Subjects in the highest BMI tertile had the lowest prevalence of retinopathy.

CONCLUSIONS

Prevalence of retinopathy and its association with HbA1c and diabetes duration is similar to that previously reported in youth with type 1 diabetes and in adults with type 2 diabetes of known duration. The mechanism underlying the reduced risk of retinopathy in the most obese individuals is unknown. Follow-up of this cohort will help define the natural history of retinopathy in youth with type 2 diabetes.

Characterization of the early course of diabetic retinopathy in adults with type 2 diabetes has been hindered by the long lag time before diagnosis. The TODAY cohort of youth with type 2 diabetes is ideal for examining the prevalence of retinopathy early in the course of the disorder.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The TODAY clinical trial enrolled 699 youth with type 2 diabetes who were 10–17 years of age. Subjects were randomized to treatment with metformin alone, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin plus intensive lifestyle intervention, and they were followed-up for 2–6.5 years (1). The TODAY CONSORT Diagram is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. In the last year, retinal examinations were obtained for 524 participants and 517 had digital fundus photographs of seven standard stereoscopic fields that were readable in at least one eye. The Fundus Photograph Reading Center at the University of Wisconsin certified retinal photographers at participating sites, and photographs were evaluated centrally by experienced graders according to an abbreviated and modified version of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Final Retinopathy Severity Scale for Persons; the scale has 17 steps, ranging from no retinopathy in either eye to high-risk proliferative retinopathy in both eyes (2).

Because no subjects had more than mild nonproliferative retinopathy (NPDR), they were coded only as having or not having retinopathy. The minimum level of retinopathy was at least one retinal lesion (microaneurysm, intraretinal hemorrhage, or cotton wool infarct) in at least one eye. Associations among retinopathy, age, diabetes duration, treatment arm, race/ethnicity, sex, and mean HbA1c and BMI during the study were examined. Each continuous variable of interest was divided into categories based on tertiles. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs, adjusted for patient age, mean HbA1c, and months since diagnosis, were calculated for each variable of interest using the first tertile as the comparison group for all calculations. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the young people in the TODAY study have been previously described (3). All participants were overweight or obese, 64.4% were female, and >80% were from racial/ethnic minority groups. The demographics of the subjects with readable fundus photographs did not differ from the larger group. Age at time of examination was 18.1 ± 2.5 years, diabetes duration was 4.9 ± 1.5 years (range, 2.0–8.4), HbA1c was 7.1 ± 1.7% (54 ± 5 mmol/mol), and BMI was 36 ± 8 kg/m2.

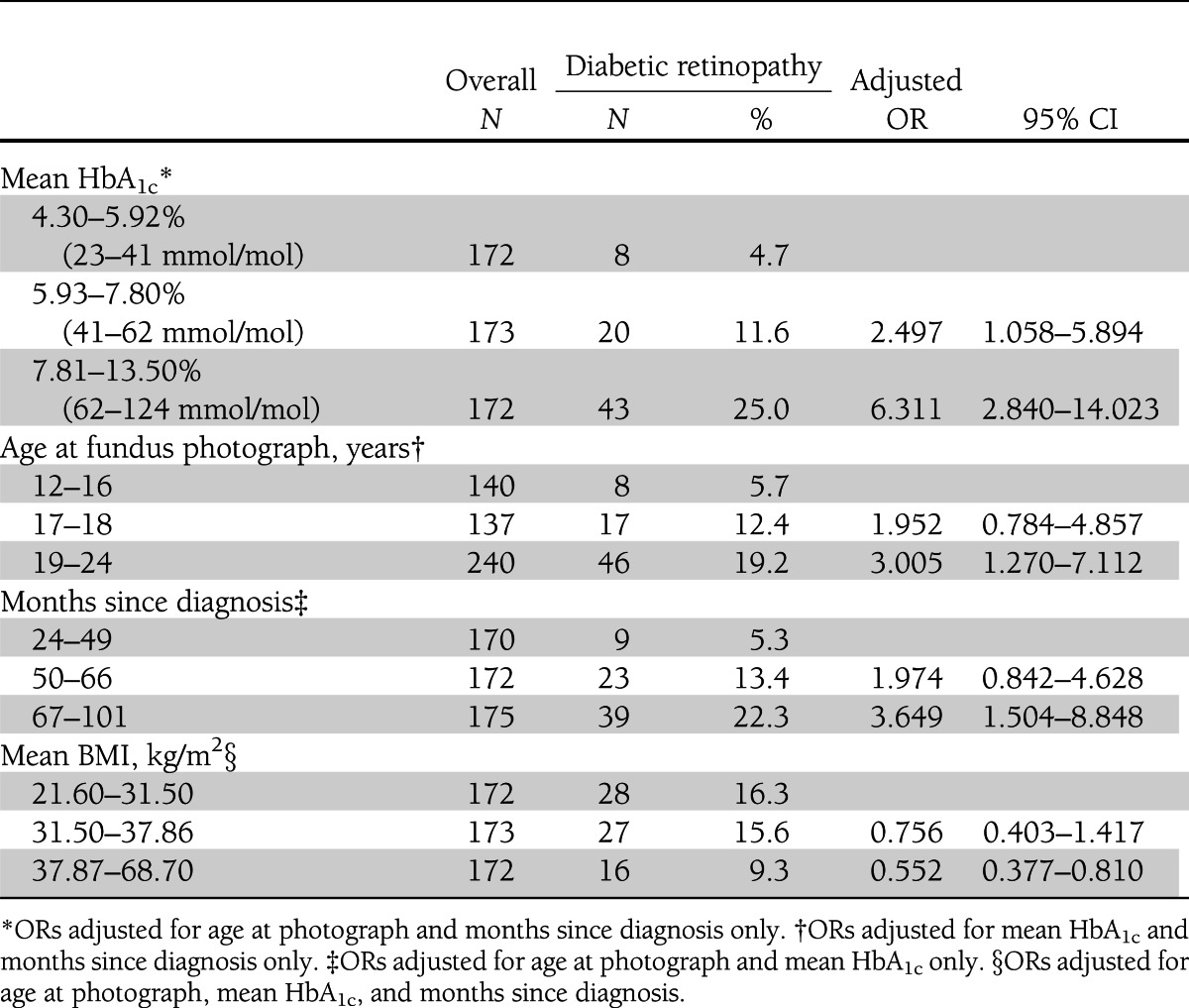

Of 517 participants, 71 had early retinopathy, with 64 having very mild NPDR (only microaneurysms or other vascular pathology such as intraretinal hemorrhage or cotton wool infarct), and 7 having mild NPDR (microaneurysms plus other vascular pathology). Of those with very mild NPDR, 46 had findings in only one eye. Of those with mild NPDR, five had mild findings in both eyes, one had involvement of a single eye, and another had very mild NPDR in the second eye. None had macular edema, advanced NPDR, or proliferative retinopathy. Lesions observed in individual eyes are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Using adjusted ORs, sex, treatment group, ethnicity, blood pressure, smoking, pregnancy, microalbuminuria, and lipids did not affect retinopathy. Compared with the group without retinopathy, participants with retinopathy had higher HbA1c (8.3 ± 1.77 [67 ± 4] vs. 6.9 ± 1.60% [52 ± 6 mmol/mol]; P < 0.0001), longer duration of diabetes (5.59 ± 1.28 vs. 4.74 ± 1.46 years; P < 0.0001), and were older (19.1 ± 2.08 vs. 17.9 ± 2.47 years; P = 0.0001). Adjusted ORs confirmed these findings (Table 1). Retinopathy was less common in subjects in the highest BMI tertile.

Table 1.

Adjusted ORs for diabetic retinopathy based on tertile of mean HbA1c, age at fundus photograph, months since diagnosis, and mean BMI

CONCLUSIONS

In TODAY, the prevalence of early retinopathy in young people with a mean duration of type 2 diabetes of 4.9 years was 13.7%. This is higher than previously reported in young Pima Indians, in whom retinopathy was detected only after age 20 years and who had diabetes >5 years. Retinopathy in that study was determined by dilated direct ophthalmoscopy, rather than by standardized fundus photographs assessed by skilled graders (4). In the SEARCH study, the prevalence of retinopathy using retinal photography was 17% for type 1 diabetes and 42% for type 2 diabetes. However, participants in the SEARCH study had known diabetes duration >5 years (mean duration, 7.2 years) and were older (mean age, 21 years) (5). A small Australian study of adolescents with type 2 diabetes <2 years reported a retinopathy prevalence of only 4% (6). Differences in methodology in these studies make direct comparisons difficult. However, retinopathy prevalence in adults who developed diabetes on follow-up in the Diabetes Prevention Program was 15.5% after slightly more than 3 years of diabetes (7). This is similar to our data obtained using the same techniques.

As in adults, increased prevalence of retinopathy in TODAY participants was associated with older age, longer diabetes duration, and glycemic control as assessed by HbA1c. The most severely obese individuals had decreased retinopathy. An association of lower weight or BMI with increased retinopathy has been reported previously in adults with type 2 diabetes and has been attributed to poor diabetes control (8). In our subjects, lower BMI was a risk factor for retinopathy even after controlling for HbA1c. This has not been previously reported in young people with type 2 diabetes. Decreased retinopathy prevalence has been linked with increased BMI, C-peptide, and C-reactive protein (9,10). This suggests a protective effect of insulin resistance, given the association of insulin and IGF-I with development of diabetic eye disease (11). Abdominal obesity may be protective compared with more generalized obesity (12). This “obesity paradox” has been recognized previously in studies of adult mortality from heart failure, hypertension, and other conditions (13). Understanding the association might help to elucidate mechanisms of the development of retinopathy and separate the effect of hyperglycemia from direct effects of insulin or the inflammatory effects of obesity.

A limitation of this study is that retinal photographs were obtained only at the end of the TODAY trial because the burdens and complexity of the clinical trial precluded baseline eye assessments (3). However, continued follow-up of the TODAY cohort will allow us to define the natural history and progression of retinopathy in this large population of youth with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed with funding from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/National Institutes of Health (grant numbers U01-DK61212, U01-DK61230, U01-DK61239, U01-DK61242, and U01-DK61254); the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Centers Program (grant numbers M01-RR00036 [Washington University School of Medicine], M01-RR00043-45 [Children’s Hospital Los Angeles], M01-RR00069 [University of Colorado Denver], M01-RR00084 [Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh], M01-RR01066 [Massachusetts General Hospital], M01-RR00125 [Yale University], and M01-RR14467 [University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center]); and the National Center for Research Resources Clinical and Translational Science Awards (grant numbers UL1-RR024134 [Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia], UL1-RR024139 [Yale University], UL1-RR024153 [Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh], UL1-RR024989 [Case Western Reserve University], UL1-RR024992 [Washington University in St. Louis], UL1-RR025758 [Massachusetts General Hospital], and UL1-RR025780 [University of Colorado Denver]).

M.W.H. serves on advisory panels for Novo Nordisk and Daiichi Sankyo, serves on a data safety monitoring committee for Bristol-Myers Squibb, and serves on a scientific advisory committee for Xeris Pharmaceuticals. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

L.L.L. researched data, contributed to the discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.P.D. researched data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.L.D. researched data, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. W.V.T. researched data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.W.H. contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L.L. researched data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. T.H.L. contributed to the discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.L.D. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Parts of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, 4–7 May 2013.

The TODAY Study Group thanks the following companies for donations in support of the study’s efforts: Becton, Dickinson and Company; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline; LifeScan; Pfizer; and Sanofi. The TODAY Study Group also gratefully acknowledges the participation and guidance of the American Indian partners associated with the clinical center located at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, including members of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service.

Materials developed and used for the TODAY standard diabetes education program and the intensive lifestyle intervention program are available to the public at https://today.bsc.gwu.edu/.

APPENDIX

The members of the writing group are as follows: Lynne L. Levitsky (chair), MD, Massachusetts General Hospital; Ronald P. Danis, MD, University of Wisconsin; Kimberly L. Drews, PhD, George Washington University; William V. Tamborlane, MD, Yale University School of Medicine; Morey W. Haymond, MD, Baylor College of Medicine; Lori Laffel, MD, Joslin Diabetes Center; and Terri H. Lipman, PhD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc12-2387/-/DC1.

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00081328, clinicaltrials.gov.

A slide set summarizing this article is available online.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the respective Tribal and Indian Health Service Institution Review Boards or their members.

A complete list of the members of the TODAY Study Group can be found in the Supplementary Data online. The members of the writing group are listed in the appendix.

References

- 1.Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, et al. TODAY Study Group Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:159–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs—an extension of the modified Airlie House classification (ETDRS report number 10). Ophthalmology 1991;98:S786–S806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitler P, Hirst K, Pyle L, et al. TODAY Study Group A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2247–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krakoff J, Lindsay RS, Looker HC, Nelson RG, Hanson RL, Knowler WC. Incidence of retinopathy and nephropathy in youth-onset compared with adult-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer-Davis EJ, Davis C, Saadine J, et al. SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group Diabetic retinopathy in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Cohort: a pilot study. Diabet Med 2012;29:1148–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eppens MC, Craig ME, Cusumano J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes complications in adolescents with type 2 compared with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1300–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The prevalence of retinopathy in impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabet Med 2007;24:137–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villena JE, Yoshiyama CA, Sánchez JE, Hilario NL, Merin LM. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Peruvian patients with type 2 diabetes: results of a hospital-based retinal telescreening program. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2011;30:408–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo S, Gentile L, Castiglione A, et al. C-peptide and the risk for incident complications and mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: a retrospective cohort study after a 14-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167:173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim LS, Tai ES, Mitchell P, et al. C-reactive protein, body mass index, and diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:4458–4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemmons D, Maile L, Xi G, Shen X, Radhakrishnan Y. Igf-I signaling in response to hyperglycemia and the development of diabetic complications. Curr Diabetes Rev 2011;7:235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raman R, Rani PK, Gnanamoorthy P, Sudhir RR, Kumaramanikavel G, Sharma T. Association of obesity with diabetic retinopathy: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study (SN-DREAMS Report no. 8). Acta Diabetol 2010;47:209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon JB, Lambert GW. The obesity paradox—a reality that requires explanation and clinical interpretation. Atherosclerosis 2013;226:47–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]