Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress occurs through free radical- and non-radical-mediated oxidative mechanisms, but these are poorly discriminated by most assays. A convenient assay for oxidants in human serum is based upon the Fe2+-dependent decomposition of peroxides to oxidize N,N′-diethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (DEPPD) to a stable radical cation which can be measured spectrophotometrically.

Methods

We investigated modification of the DEPPD oxidation assay to discriminate color formation due to non-radical oxidants, including hydroperoxides and endoperoxides, which are sensitive to ebselen.

Results

Use of serum, which has been pretreated with ebselen as a reference, provides a quantitative assay for non-radical, reactive oxidant species in serum, including hydroperoxides, endoperoxides and epoxides. In a set of 35 human serum samples, non-radical oxidants largely accounted for DEPPD oxidation in 86% of the samples while the remaining 14% had considerable contribution from other redox-active chemicals.

Conclusions

The simple modification in which ebselen-pretreated sample is used as a reference provides means to quantify non-radical oxidants in human serum. Application of this approach could enhance understanding of the contribution of different types of oxidative stress to disease.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, cardiovascular disease, peroxides, hydroperoxides, endoperoxides, epoxides

1. Introduction

Circumstantial evidence indicates that oxidative stress is a component of many chronic and age-related diseases, yet evidence from large-scale, double-blind interventional trials with the free radical-scavenging antioxidants, vitamins C and E, provides little support for involvement of free radical mechanisms [1]. An alternative hypothesis is that the quantitatively important oxidative reactions contributing to disease involve non-radical oxidant species, such as peroxides, which disrupt redox signaling and control mechanisms [2]. However, distinction between radical and non-radical mechanisms of injury is technically challenging, especially when both free radicals and non-radical oxidants are present in a biologic system.

Another difficulty concerns the nature of oxidants relevant to disease risk. Although much of the oxidative stress literature focuses on highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are short-lived in biologic systems, many studies show that there are relatively stable oxidants which persist in human serum even after months of storage at -80° C. The latter have been termed “reactive oxygen metabolites”, for which we use the generic term “ROM” in the present manuscript. ROM in serum can be operationally defined by a reaction with N,N′diethyl-para-phenylenediamine (DEPPD) in the presence of Fe2+, which produces a stable radical cation (Fig. 1A) easily measured using a spectrophotometer because it is a red chromophore [3].

Fig. 1.

(A) The reaction between a free radical and DEPPD results in the formation of a stable radical that can be measured at absorbance of 505 nm. (B) The multi ring structure of the antioxidant, ebselen.

This reaction is the basis for the popular d-ROMs assay (Diacron International, Italy; www.diacrom.com) [3] and similar FORT (Free Oxygen Radicals Test; INCOMAT Mediznische, Glashutten, Germany). These tests are simple, relatively inexpensive and have been widely used to measure oxidative stress in human serum [4-11]. Importantly, the results of studies from different research groups suggest that these tests could be useful to assess disease risk. Such use is limited by uncertainty about the chemical nature of ROM.

The ROM test is standardized relative to tert-butylhydroperoxide or H2O2, giving the impression that the test is measuring H2O2 and organic peroxides in serum. However, H2O2 and many hydroperoxides are relatively unstable and would not be expected in serum at concentrations indicated by the DEPPD reaction. Moreover, background chromophores as well as other oxidative reactions, e.g., ceruloplasmin activity [3] can contribute to the spectral change. Use of an EDTA-containing blank can correct for background chromophores; however, EDTA inhibits both peroxide-dependent color formation and ceruloplasmin activity so that an EDTA control does not discriminate factors contributing to the DEPPD oxidation by serum.

Antioxidants, such as butylated hydroxytoluene, added to serum could block DEPPD oxidation, but would not discriminate between the types of oxidants present in the sample. In the present study, we examined whether ebselen, a selenium-containing chemical which reduces peroxides in the presence of thiols [12], could be used to improve the specificity of the DEPPD reaction for peroxides in human serum. Ebselen, 2-phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)one (Fig. 1B), catalyzes thiol-dependent reduction of peroxides by a non-radical mechanism [12,13]. Although earlier literature suggested that ebselen has properties such as free radical quenching [12], this activity was subsequently shown to have little effect [14]. Sequential reduction of ebselen by glutathione produces a selenol which is the direct reductant for the peroxides [13].

The present research shows that ebselen pretreatment of serum largely eliminates the serum-dependent oxidation of DEPPD. Studies with a purified endoperoxide and two epoxides show that, in addition to previously characterized oxidation of DEPPD by hydroperoxides, both of these oxidants support the DEPPD oxidation reaction and are eliminated by pretreatment with ebselen. Use of an imidazole N-oxide to trap radicals provided further evidence that the radical products are derived from non-radical species. Thus, use of an ebselen-pretreated serum sample as a reference for the DEPPD-dependent spectrophotometric assay provides means to improve specificity for non-radical oxidants in serum. This simple, yet novel, approach provides means to discriminate ebselen-dependent and ebselen-independent oxidative mechanisms that contribute to the DEPPD signal and potentially can be useful for population studies to test for distinct associations of disease risk with non-radical and radical mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

N,N-diethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (DEPPD), tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBH), FeSO4, bathocuproine disulfonate (BCDS), glutathione peroxidase (bovine erythrocyte, Gpx), catalase, microsomal epoxide hydrolase (human, EH), rhodococcus epoxide hydrolase (EHr), styrene oxide, and 16,17-epoxy-21-acetoxy-pregnenolone were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Peroxiredoxin-1 (human) was purchased from Lab Frontier (Seoul, South Korea). Ebselen [yl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)one]urchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Other chemicals were of reagent grade and purchased locally.

Human studies were conducted with approval of the Emory University Investigational Review Board. Some serum samples for methods development were obtained commercially.

2.2 Methods

Experimentation was performed in 4 parts, with the goals to 1) adapt the DEPPD assay as developed by Alberti et al. [3] to a 96-well plate format and test it against a commercially available kit, 2) use selective chemical reactivity and enzymatic activity to gain information on the chemical nature of ROM in serum and 3) test model endoperoxide and epoxides to determine whether these classes of chemicals could be components of ROM in plasma and 4) compare the original Alberti assay to those obtained using an ebselen blank to determine whether this modification could improve specificity for the assay.

The final standard protocol adapted from Alberti et al. [3] for a 96-well plate format was as follows: Serum samples were diluted 1:40 in acetate buffer (37.32 mmol/l, pH 4.8). Five microliter aliquots were transferred to adjacent rows in 96-well plates with 100 μl of acetate buffer without or with 5 μl of 1 mmol/l ebselen in DMSO (50 μmol/l final concentration). Control experiments with DMSO without ebselen showed that DMSO had no effect on the color formation at the volume added. After 6 min at room temperature with shaking, 10 μl of 3.9 mmol/l DEPPD with 2.8 mmol/l FeSO4 was added with a multi-channel pipette, and samples were shaken for 6 min prior to reading absorbance at 505 nm on a multiwell platereader. Values are reported as ΔA505 at 6 min using as reference wells which were identically treated except for substitution of EDTA for Fe2+. The ΔA505 can be readily converted to peroxide equivalents using the tBH standard curve or to Carr units [3], which are arbitrary units corresponding to 0.08 mg H2O2 per 100 ml (24 μmolo/l). Where used, the FORT kit (INCOMAT Medizinische, Glashutten, Germany) was performed according to manufacturer's instructions.

For studies of the chemical nature of ROM in plasma, reagents were prepared at pH 7.0 and added to serum without adjustment of pH of the serum. Pretreated serum aliquots were then added to acetate buffer and DEPPD was added. Absorbance was scanned over the range of 450 to 575 nm, with data reported for the scans taken at 6 min after addition of either Fe2+ or EDTA. Concentrations of agents used for pretreatments were as follows: bathocuproine disulfonate, 1 mmol/l; Na2S, 50 μmol/l and 5 mmol/l; GSH 100 μmol/l and 5 mmol/l; Cys, 50 μmol/l and 5 mmol/l; ebselen, 0.03, 0.12, 0.5 and 1 mmol/l; microsomal epoxide hydrolase, 0.2 mg/ml; rhodococcus epoxide hydrolase, 0.2 mg/ml; peroxiredoxin-1, 0.1 mg/ml; glutathione peroxidase-1, 50 units/ml (dialyzed to remove dithiothreitol); catalase, 0.2 mg/ml (dialyzed to remove thymol).

Assays with peroxides and epoxides were performed under identical conditions as above, with respective solutions replacing serum. Concentrations added were as follows: PGH2, 90 μmol/l; 16,17-epoxy-21-acetoxy-pregnenolone, 1 mmol/l; styrene oxide, 1 mmol/l. For each experiment with purified peroxide or epoxide, a parallel experiment was performed in which the peroxide or epoxide was added along with serum so that the experiment was conducted with the same matrix. Results were qualitatively the same as the results shown and, therefore, are not included.

Spin trapping experiments were performed using 4-carboxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-imidazole-1-oxide (CDMIO, Alexis Corp). This anionic spin trap is resistant to reduction by ascorbate and therefore useful to trap free radicals in the serum [15]. Conditions used were 500 mmol/l CDMIO, 200 μmol/l FeSO4, 15% (v/v) serum in acetate buffer. ESR settings were as described previously [16].

3. Results

3.1 DEPPD-dependent color formation with human serum

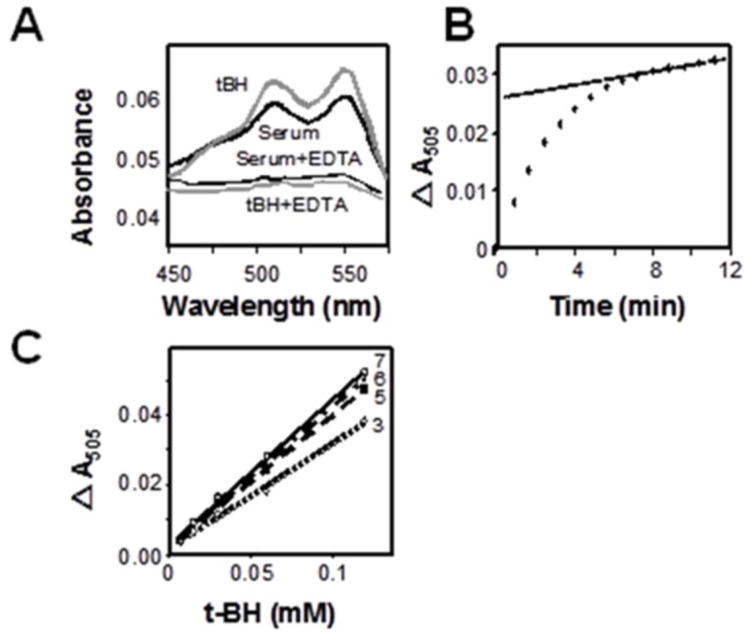

Previous research showed that hydroperoxides in the presence of Fe2+ oxidize DEPPD and that this reaction is blocked by EDTA, a metal ion chelator [3]. We initially performed experiments to adapt the principles of the previous research to a 96-well plate format. In this development, we observed that DEPPD oxidation occurred with serum and tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBH) and that both were inhibited by EDTA (Fig. 2A). Time course studies showed that two phases of oxidation were present, one which appeared as a continuous background oxidation, perhaps due to slow oxidation of proteins, and the other which was an oxidation complete by 6 min (Fig. 2B). At the 6-min time point, the contribution of background oxidation was minimal and the signal due to the “pre-formed” oxidant was maximal (Fig. 2C); thus, analyses were performed with a format in which oxidation at 6 min was measured. Comparisons of data for 3, 5, 6, and 7 min showed that the A505 was linearly dependent upon added tert-butyl hydroperoxide standard (7 to 120 μmol/l) over this time frame (r2 = 0.99; Fig. 2C). A direct comparison of the 96-well plate format to the commercial FORT kit showed that the adapted 96-well plate format provided values equal to 101 ± 4% of the FORT assay values (Table 1). Within day CV values were 6.0 for the FORT kit and 6.5 for the 96-well plate assay; corresponding between-day CV were 5.8 and 5.3, respectively (Table 1). Thus, the data show that the ROM test can be adapted to a multi-well plate format which is comparable to the standardized FORT kit. This allows large numbers of samples to be rapidly measured.

Fig. 2.

Adapatation of DEPPD oxidation assay of serum oxidant to a 96-well plate format. Ferrous iron-dependent oxidation of DEPPD by serum was assayed using conditions of Alberti et al. [3] and compared to oxidation by 50 μM tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBH). A) Absorbance scan from 450 to 575 nm performed 6 min after addition of serum or tBH. Results are shown without and with 1 mmol/l EDTA. B). Time course of reaction measured at 505 nm showed that the color change appeared to occur with 2 phases, a rapid phase which was maximal at 6 min and a slow phase which was linear with time. C) Standard curves performed with tBH at different timed intervals showed that the DEPPD oxidation was linearly dependent upon tBH and was not significantly different for times of 5-7 min. Thus, a standard assay time of 6 min was selected to approximate maximal signal from the initial phase oxidation while maintaining a minimal contribution from the slow phase oxidation. Data from representative experiment; similar results were obtained using sera from 4 individuals.

Table 1. Comparison of the multiwell plate-adapted method for measurement of ROM using DEPPD oxidation in the presence of Fe2+ to results obtained with the commercially available FORT kit.

| Within day | Between day | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Method | ||

| FORT kit (Carr Units) (Low) | 273 ± 31 | 270 ± 23 |

| CV (%) | 11 | 8.6 |

| (High) | 495 ± 5 | 485 ± 16 |

| CV (%) | 1.0 | 3.2 |

| Overall CV (%, n=4) | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| Microplate (Carr Units) (Low) | 295 ± 21 | 288 ± 20 |

| CV (%) | 7.1 | 6.8 |

| (High) | 478 ± 22 | 465 ± 19 |

| CV (%) | 5.0 | 4.8 |

| Overall CV (%, n=4) | 6.5 | 5.3 |

| Microplate value as percentage of FORT value (n=4) | 101 ± 4 | 99 ± 0.5 |

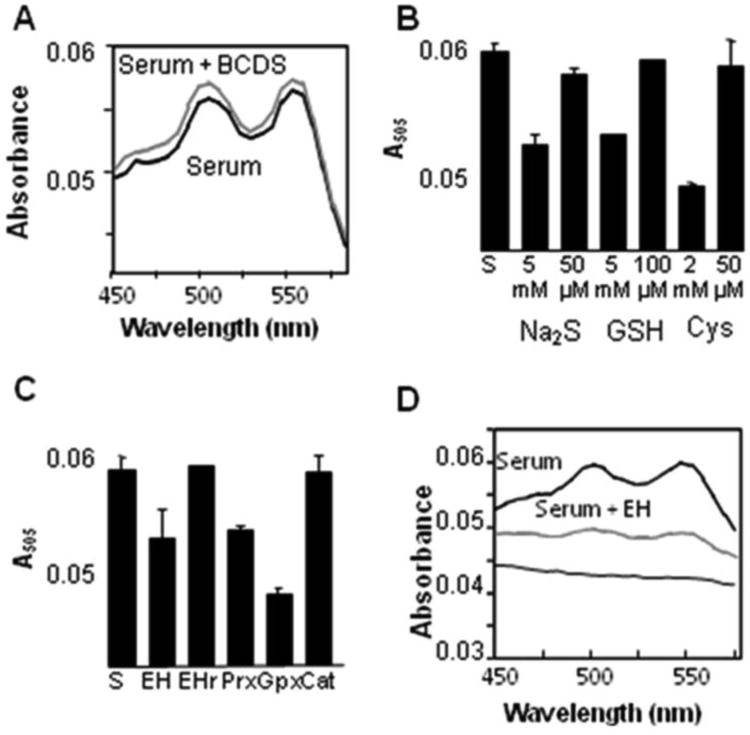

To test for the contribution of the ferroxidase activity of the copper-dependent enzyme, ceruloplasmin, to DEPPD oxidation, we pretreated serum with the copper chelator bathocuproine disulfonate (BCDS). Results showed that BCDS did not cause a significant decrease in DEPPD oxidation, indicating that the timed method as described had minimal contribution from ceruloplasmin (Fig. 3A). We next tested the effects of thiols on serum-dependent DEPPD oxidation. Results showed that Na2S, cysteine and GSH each prevented the accumulation of the DEPPD cation radical. However, at low concentrations of thiols as found in serum, no effects were observed in the assay (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3.

Factors affecting serum-dependent oxidation of DEPPD. A) Serum samples were assayed for DEPPD oxidation with 1 mmol/l of the specific copper chelator, bathocuproine disulfonate (BCDS). B) Serum samples were assayed for DEPPD oxidation with either 5 mmol/l or 50 μM Na2S, 5 mmol/l or 50μM GSH or 2 mmol/l or 50 μM cysteine (Cys). C) Serum samples were assayed for DEPPD oxidation with microsomal epoxide hydrolase (EH), rhodococcus epoxide hydrolase (EHr), peroxiredoxin-1 (Prx), glutathione peroxidase-1 plus 50 μmol/l GSH (labeled Gpx) and catalase (Cat). D) Spectral analysis of reaction following pretreatment of serum with microsomal epoxide hydrolase (EH). EDTA-treated control is shown for reference. Spectra are representative for at least 3 individuals. Other data are mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Studies were performed to detect endogenous oxidants in serum which could contribute to DEPPD oxidation. For this, we preincubated serum with catalase, GSH peroxidase-1, peroxiredoxin-1 and epoxide hydrolase (microsomal and rhodococcus). Results showed decreased signal for all except rhodococcus epoxide hydrolase and catalase (Fig. 3C). The microsomal epoxide hydrolase partially decreased the signal (EH, Fig. 3C,D), but the rhodococcus enzyme did not (EHr, Fig. 3C). GSH peroxidase-1 pretreatment effectively eliminated the serum-dependent DEPPD oxidation (Gpx, Fig. 3C); peroxiredoxin-1 decreased but did not totally eliminate the oxidation (Prx, Fig. 3C). Catalase was dialyzed to remove thymol and did not protect against oxidants (Cat, Fig. 3C). These data show that peroxides, which could include hydroperoxides and endoperoxides, contribute to DEPPD oxidation. The lack of effect of pretreatment with catalase shows that the H2O2 in serum does not provide a significant contribution to the signal. The data suggest that epoxides could also contribute to the signal.

To test the effect of the GSH peroxidase mimetic, ebselen, on serum-dependent DEPPD oxidation, we performed experiments with increasing concentrations of ebselen. Earlier data show that ebselen effectively reduces hydroperoxides by thiol-dependent mechanisms [17,18]. Results with serum showed that ebselen pretreatment caused a concentration-dependent loss of signal (Fig. 4A). Time course studies showed that the effect was time-dependent; simultaneous addition of ebselen with DEPPD did not completely block color formation, while pretreatment with 1 mmol/l gave essentially complete inhibition (Fig. 4B,C). Addition of ebselen after formation of color had no effect (Fig. 4B), indicating that ebselen does not reduce the DEPPD radical cation but rather eliminates oxidants which contribute to DEPPD oxidation.

Fig. 4.

Decrease in DEPPD oxidation due to pretreatment of human serum with the GSH peroxidase mimetic, ebselen. A) Samples were pretreated with ebselen for 6 min at concentrations indicated. In separate experiments (not shown), pretreatment with 1 mmol/l ebselen provided approximately the same loss of signal as 0.5 mmol/l, and was adopted as the standard procedure. B) Addition of 1 mmol/l ebselen to samples after color formation (Post) did not decrease color. Controls were the standard assay with serum plus Fe2+ and DEPPD (None), and assay with serum pretreated with 1 mmol/l ebselen (Pre). C) Spectra resulting from ebselen-pretreated serum compared to same serum without ebselen. D) A typical ESR spectrum of free radical detection by CDMIO in the presesnce of tert-butylhydroperoxide + Fe2+ which identifies both C- and O-centered radical adducts. E) An ESR spectrum of serum + Fe2+ +CDMIO which shows mostly a signal typical of -O-centered radicals. F) Preincubation of serum with ebselen prior to addition of Fe2+ +CDMIO shows loss of signal from oxygen-centered radicals (Fig. 4F). Spectra for A-C are representative of samples from at least 3 individuals. Other data are mean ± SEM (n = 4).

To further test the characteristics of ebselen-sensitive oxidants detected by DEPPD, samples were analzed by ESR spectroscopy using CDMIO as a spin-trapping agent [15]. CMDIO is a 2H-imidazole-1-oxide which traps C- and O-centered radicals and is well suited for studies of radical species in serum because it is not reduced by ascorbate. Figure 4D shows a typical ESR spectrum of free radical detection by CDMIO in the presesnce of tert-butylhydroperoxide + Fe2+ in which both C- and O-centered radical adducts are identified. An ESR spectrum of serum + Fe2+ +CDMIO shows mostly a signal typical of O-centered radicals (Fig. 4E). Preincubation of serum with ebselen inhibited spin trapping of oxygen centered radical (Fig. 3F). Because ebselen is known to have peroxidase activity and the previous experiment with catalase (Fig. 3) showed that the peroxide is not H2O2, the results allow the assignment as a lipid-derived alkoxyl radical (·O-L). This assignment was made due to the fact that lipid peroxyl radicals are difficult to detect with ESR and that these radicals will degrade to alkoxyl radicals which can be detected [19]. Of note, this lipid-derived alkoxyl radical adduct was the major species found in the spectra; the second radical adduct represented the spin trapping of carbon-centered radicals, which were present in a lesser amount. Thus, ebselen pretreatment eliminates the lipid peroxides which contribute to DEPPD oxidation by serum.

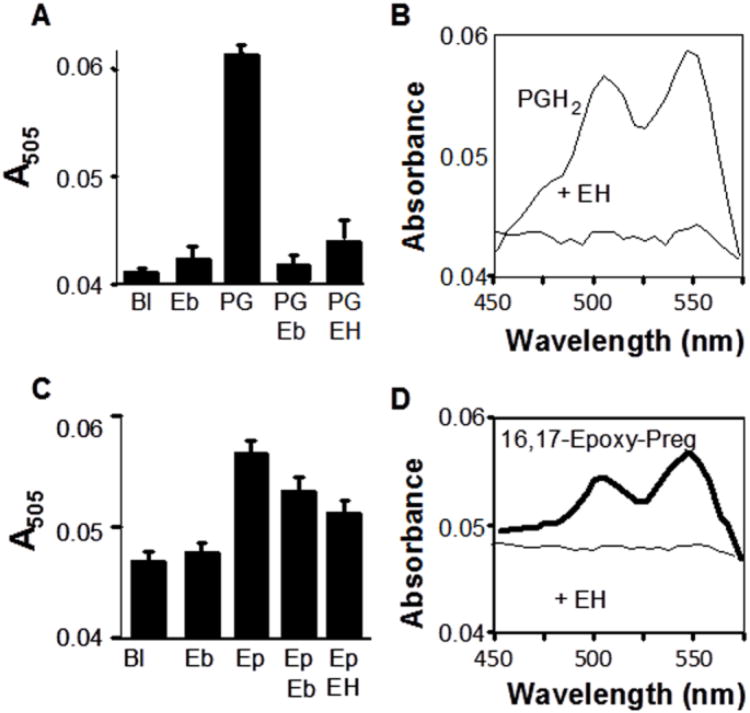

We examined whether endoperoxides could contribute to DEPPD oxidation by testing prostaglandin H2, PGH2. Results showed that 90 μmol/l PGH2 oxidized DEPPD in the presence of Fe2+ and that this reaction was prevented by pretreatment of PGH2 with ebselen (Fig. 5A,B). The extent of oxidation was about half that caused by 100 μmol/l tBH (not shown), indicating that the endoperoxide oxidizes DEPPD, but the extent of this reaction may be about half of that provided by hydroperoxides. Thus, in addition to hydroperoxides, ebselen reacts with endoperoxides. Consequently, the data show that ebselen pretreatment of serum allows detection of the sum of hydroperoxides and endoperoxides but does not allow distinction between these forms.

Fig. 5.

Oxidation of DEPPD by the endoperoxide prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) and 16, 17-epoxy-21-acetoxy-pregnenolone (Ep). Preliminary experiments were performed to determine concentration ranges for assay with PGH2, Ep and styrene oxide. Results showed that 90 μmol/l PGH2 and 1 mmol/l Ep produced a signal but 1 mmol/l styrene oxide did not. A) Standard 6-min assay with addition of 90 μmol/l PGH2 (PG) instead of serum. Pretreatment with ebselen (Eb) or microsomal epoxide hydrolase (EH) eliminated signal. B) Spectrum showing elimination of signal by pretreatment with EH. C. Standard 6-min assay with addition of 1 mmol/l Ep instead of serum. Pretreatment with ebselen (Eb) decreased the signal and with microsomal epoxide hydrolase (EH) largely eliminated the signal. C. Spectrum showing signal generated by 1 mmol/l Ep and loss of signal by pretreatement with EH. Bl, Blank.

As a control for the data showing that microsomal epoxide hydrolase pretreatment decreased serum-dependent DEPPD oxidation, we pretreated PGH2 with microsomal epoxide hydrolase. Results showed a decrease in PGH2-dependent DEPPD oxidation (Fig. 5A). The same pretreatment with rhodococcus epoxide hydrolase had no effect (not shown). The results are consistent with the microsomal epoxide hydrolase preparation having endoperoxidase activity.

To test whether epoxides could contribute to DEPPD oxidation as suggested by the results of epoxide hydrolase pretreatment of serum (Fig. 3), we measured oxidation of DEPPD by styrene oxide and 16,17-epoxy-21-acetoxy-pregnenolone [Preg(O)]. Styrene oxide resulted in no Fe2+-dependent DEPPD oxidation, even at 1 mmol/l concentration (data not shown). Experiments with Preg(O) showed that oxidation of DEPPD occurred with relatively high (1 mmol/l) concentration (Fig. 5C,D). This oxidation was blocked by pretreatment with microsomal epoxide hydrolase or ebselen (Fig. 5C,D). Consequently, one must conclude from the data on epoxide hydrolase pretreatment of serum (Fig. 3) and direct studies with purified epoxides (Fig. 5) that the non-radical species in serum are likely to include epoxides but with low color yield. This indicates that comparison of ebselen pretreated samples to the standard DEPPD oxidation assay provides a means to quantify non-radical oxidants, including hydroperoxides, endoperoxides and possibly epoxides, but does not discriminate between these classes of chemicals.

Although the data show that the DEPPD oxidation test measures peroxides and epoxides in serum, the data do not show the extent to which the ebselen-dependent DEPPD signal corresponds to the standard ROM assay described by Alberti et al. [3]. A direct comparison of the ebselen-dependent assay for non-radical oxidant species with the original method for DEPPD oxidation [3] is shown in Figure 6. For most samples, the methods are completely comparable. However, considerable differences are present in 14% of the samples. The comparable signals in most of the samples support the interpretation that the measurement of DEPPD oxidation largely represents non-radical oxidants. The data also show that a more specific assessment of the ebselen-dependent signal, such as by mass spectrometry, may provide a better means to assess the contribution of non-radical oxidants to disease. In addition, samples in which a tight association is not seen may represent a qualitatively unique pattern of oxidants which contribute to distinct oxidant mechanisms in disease.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of human serum oxidants assayed by DEPPD oxidation with ebselen-pretreated reference (ebs-ROS) to standard analysis without pretreatment (d-ROMs). Samples were assayed by standard 6-min timed DEPPD oxidation in the presence of Fe2+ and compared to results using matched serum samples pretreated with 1 mmol/l ebselen as references.

4. Discussion

Much of oxidative stress research has been focused on free radical mechanisms yet large-scale interventional trials with moderately high intakes of two of the best characterized free radical scavenging antioxidants, vitamins C and E, provided little evidence for benefit [1]. An alternative, non-radical hypothesis for oxidative stress has been proposed based upon the evidence that free radicals represent only a small fraction of the total oxidant load [2]. In this hypothesis, non-radical oxidants are proposed to be the quantitatively important reactive species under many, if not most, conditions where oxidative stress contributes to disease. Ironically, the assays based upon DEPPD oxidation, which were founded upon free radical principles and utilize a stable radical cation to quantify oxidants, largely, according to the data presented here, measure non-radical oxidant species in serum. The oxidation of DEPPD to the radical cation is dependent upon Fe2+ to transfer electrons to relatively stable non-radical oxidants in serum [3]. Under conditions of the assay, 2 oxidative phases are apparent; the assay as described is optimized (timed assay at 5-7 min) to measure the pre-existing stable oxidants and to minimize the contribution of other oxidative processes. A slower background oxidative reaction is likely to represent ongoing oxidant generation, including those of ceruloplasmin, protein oxidation and free radical reactions.

The general agreement between the standard assay for oxidation of DEPPD by serum and the ebselen-sensitive oxidant assay indicates that the former mostly measures non-radical oxidants. While it is possible that ebselen could quench singlet oxygen [12], this reaction is considered sluggish [14] and we do not consider singlet oxygen as a likely candidate for ROM in serum. It should be noted that previous research by Hassan and colleagues has shown that ebselen does not completely prevent Fe(II)-mediated increases in TBARS at acid pH [20]. We did not study the pH dependence of ebselen-dependent loss of DEPPD oxidation, but our spectral analysis and ESR data show that the signal was lost following treatment with ebselen. Consequently, we conclude that under the conditions of the preincubation, ebselen largely eliminated the serum-dependent oxidation of DEPPD. In this reaction, exogenously added thiol was not required for the reduction. Because 50 μmol/l H2S, 50 μmol/l Cys or 100 μmol/l GSH had little effect on DEPPD oxidation in the absence of ebselen (Fig. 4), we conclude that endogenous thiol content of serum is probably <100 μmol/l, and due to the fact that the concentration of oxidants present in the serum are typically in the nanomolar range [20-22], the 50 μmol/l concentration of ebselen used is in significant excess and will not require thiol equivalents to recycle the antioxidant.

The present data with PGH2 shows that endoperoxides, in addition to the usually characterized hydroperoxides, can contribute to the signal. Additional analyses of lipid components could be conducted by using a methanol extraction and further analysis. Thus, endoperoxides in serum are not distinguished from hydroperoxides and, if present, contribute to the DEPPD oxidation signal. Additionally, the inability of catalase to prevent DEPPD oxidation by serum indicates that H2O2 contributes little to the signal.

If one assumes that epoxide hydrolase is specific for epoxides, the results indicate that approximately 50% of the non-radicals in serum are epoxides. The inhibition of PGH2-induced DEPPD oxidation by epoxide hydrolase, however, also allows the interpretation that epoxides contribute little to the total signal and that endoperoxides may account for the epoxide-hydrolase-dependent signal. Additional characterization of the enzymatic specificities of the epoxide hydrolases employed in this study, along with chemical analyses of their products, is needed to distinguish these possibilities.

The discrepancy between analyses without and with ebselen for about 15% of the samples (Fig. 6) indicates that some serum samples contain large amounts of redox components other than peroxides and epoxides. This discrepancy could represent a subset with qualitative differences in serum oxidative chemistry, i.e., ones with a high amount of free radical reactions or oxidants which are not reactive with ebselen. Importantly, the previously observed associations of DEPPD oxidation with disease risks could be due to the ebselen-dependent component or the ebselen-independent component. Application of the methods as described to population studies will allow for the discrimination of the non-radical oxidative species in serum from the residual signal. Such analyses could be helpful in understanding the association of ROM test results with pathologies such as cardiovascular disease and atrial fibrillation [23, 24].

In summary, this present study validates a multi-well, microplate format for the popular assays of reactive oxygen metabolites in human serum based upon DEPPD oxidation and an adapted form of the assay in which ebselen is used to eliminate non-radical oxidants. The non-radical oxidants include hydroperoxides, endoperoxides and possibly epoxides, but the assay does not discriminate between these oxidative species.

A relatively small subset of samples had a discordant response between assays with and without ebselen, which could represent a qualitatively distinct form of oxidant in these samples. Finally, we conclude that the ROM tests, including commercial kits based upon the same principles, largely measure non-radical reactive oxygen metabolites (NR-ROM) and that the specificity of the test for measuring NR-ROM can be improved by using corresponding ebselen-pretreated samples as references. This adaptation can allow for high throughput ROM analyses and application of this assay to population studies may, therefore, provide an approach to distinguish risks associated with non-radical and radical oxidative components of human serum.

Highlights

We modified a simple assay in order to distinguish non-radical from radical species

Human serum was pretreated with ebselen to determine non-radical involvement

Non-radical species largely account for derum-mediated DEPPD oxidation

This assay can enhance understanding of contribution of different oxidants to disease

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants ES011195 and ES009047, RR00039, DK067167, DK075745 and the Woodruff Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jones DP. Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1865–1879. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DP. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C849–868. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti A, Bolognini L, Macciantelli D, Caratelli M. The radical cation of N,N-diethyl-para-phenylendiamine: a possible indicator of oxidative stress in biological samples. Res Chem Intermed. 2000;26:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarone MR, Belcaro G, Carratelli M, et al. A simple test to monitor oxidative stress. Int Angiol. 1999;18:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson JL, Hooper WC, Jones DP, et al. Association between novel oxidative stress markers and C-reactive protein among adults without clinical coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accinni R, Rosina M, Bamonti F, et al. Effects of combined dietary supplementation on oxidative and inflammatory status in dyslipidemic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelli U, Terranova R, Luca S, Cornelli M, Alberti A. Bioavailability and antioxidant activity of some food supplements in men and women using the D-Roms test as a marker of oxidative stress. J Nutr. 2001;131:3208–3211. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.12.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis L, Stonehouse W, Loots du T, et al. The effects of high walnut and cashew nut diets on the antioxidant status of subjects with metabolic syndrome. Eur J Nutr. 2007;46:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s00394-007-0647-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vecchi AF, Novembrino C, Lonati S, Ippolito S, Bamonti F. Two different modalities of iron gluconate i.v. administration: effects on iron, oxidative and inflammatory status in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1709–1713. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flore R, Gerardino L, Santoliquido A, Catananti C, Pola P, Tondi P. Reduction of oxidative stress by compression stockings in standing workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2007;57:337–341. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natali A, Baldi S, Vittone F, et al. Effects of glucose tolerance on the changes provoked by glucose ingestion in microvascular function. Diabetologia. 2008;51:862–871. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sies H. Ebselen, a selenoorganic compound as glutathione peroxidase mimic. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;14:313–323. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90028-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugesh G, du Mont WW, Sies H. Chemistry of biologically important synthetic organoselenium compounds. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2125–2179. doi: 10.1021/cr000426w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sies H. Ebselen: a glutathione peroxidase mimic. Methods Enzymol. 1994;234:476–482. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)34118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dikalov S, Kirilyuk I, Grigor'ev I. Spin trapping of O-, C-, and S-centered radicals and peroxynitrite by 2H-imidazole-1-oxides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:616–622. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite with uric acid in the presence of ascorbate and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendel A, Fausel M, Safayhi H, Tiegs G, Otter R. A novel biologically active seleno-organic compound--II. Activity of PZ 51 in relation to glutathione peroxidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:3241–3245. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller A, Cadenas E, Graf P, Sies H. A novel biologically active seleno-organic compound--I. Glutathione peroxidase-like activity in vitro and antioxidant capacity of PZ 51 (Ebselen) Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:3235–3239. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dikalov SI, Mason RP. Reassignment of organic peroxyl radical adducts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:864–872. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan W, Ibrahim M, Nogueira CW, et al. Enhancement of iron-catalyzed lipid peroxidation by acidosis in brain homogenate: comparative effect of diphenyl diselenide and ebselen. Brain Res. 2009;1258:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa F, Shimizu K, Muroi E, et al. Serum levels of 8-isoprostane, a marker of oxidative stress, are elevated in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:815–818. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padurariu M, Ciobica A, Hritcu L, Stoica B, Bild W, Stefanescu C. Changes of some oxidative stress markers in the serum of patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 469:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abramson JL, Hooper WC, Jones DP, et al. Association between novel oxidative tress markers and C-reactive protein among adults without clinical coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuman RB, Bloom HL, Shukrullah I, et al. Oxidative stress markers are associated with persistent atrial fibrillation. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1652–1657. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.083923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]