Abstract

Background

Treatment at Level I/II trauma centers improves outcomes for patients with severe injuries. Little is known about the role of physicians’ clinical judgment in triage at outlying hospitals. We assessed the association between physician caseload, case mix, and the triage of trauma patients presenting to non-trauma centers.

Methods

A retrospective cohort analysis of patients evaluated between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 by emergency physicians working in eight community hospitals in western Pennsylvania. We linked billing records to hospital charts, summarized physicians’ caseloads, and calculated rates of under-triage (proportion of patients with moderate to severe injuries not transferred to a trauma center) and over-triage (proportion of patients transferred with a minor injury). We measured the correlation between physician characteristics, caseload and rates of triage.

Results

29 (58%) of 50 eligible physicians participated in the study. Physicians had 16.8 (SD=10.1) years of post-residency clinical experience; 21 (72%) were board-certified in Emergency Medicine. They evaluated a median of 2,423 patients/year, of whom 148 (6%) were trauma patients and 3 (0.1%) had moderate to severe injuries. The median under-triage rate was 80%; the median over-triage rate was 91%. Physicians’ caseload of patients with moderate to severe injuries was inversely associated with rates of under-triage (correlation coefficient −0.42, p=0.03). Compared to physicians in the lowest quartile, those in the highest quartile under-triaged 31% fewer patients.

Conclusions

Emergency physicians working in non-trauma centers rarely encounter patients with moderate to severe injuries. Caseload was strongly associated with compliance with American College of Surgeons – Committee on Trauma guidelines.

Keywords: trauma triage, guidelines, volume-outcome

The American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT), the Institute of Medicine, and federal and state governments promote trauma regionalization (i.e. tiered levels of care) as a cost-effective way to match illness severity with resources.1–3 ACS-COT clinical practice guidelines recommend that all patients with moderate to severe injuries receive care at trauma centers.1 Regionalization is promoted via a nationwide provider education program (Advanced Trauma Life Support [ATLS]), an accreditation program that designates selected hospitals as regional trauma centers, and the promotion of local “trauma systems” comprised of networks of hospitals with inter-facility transfer agreements.1 Despite these efforts, more than 30% of all patients with moderate to severe injuries are not treated at trauma centers (under-triage).4 This figure reflects the product of triage in the field by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel and triage in the emergency department of non-trauma centers by physicians. Among patients taken first to a non-trauma center, under-triage rates are as high as 70%.5

This under-triage is typically attributed to institutional factors (e.g. distance to a trauma center, ambulance availability, quality of the trauma system)6,7 or to patient factors (e.g. age, type of injury).8,9 Little is known about the influence of physician factors on under-triage.

In the current study, we examined the association between caseload, case mix, and physician decision making by assessing practice variation at several non-trauma centers within a single trauma system, using on retrospective review of electronic health records. We hypothesized that if triage reflected individual physician’s clinical judgment, then physicians with larger caseloads would have lower rates of under-triage.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of trauma patients evaluated between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 by a sample of emergency physicians working in the eight community hospitals run by a large healthcare system in western Pennsylvania for which we had electronic billing and medical data access.

Physician Sample

One physician group exclusively staffs all of the Emergency Departments (EDs) of community hospitals run by the healthcare system. It employs approximately 50 physicians at the eight hospitals, who work a mean of 15 ten-hour shifts per month. We recruited all emergency physicians working at these hospitals, requesting their consent to analyze the medical records of patients whom they had evaluated. Participating physicians provided information about their age, sex, race, certification, education, and experience (i.e. board certification, residency, years since completion of residence, and ATLS certification).

Patient Identification

We identified patient visits through the billing records of the ED physician group. We included all patients seen in the ED, between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010. Physician billing records were matched by name and date of service to the hospital medical record discharge abstract in the health system’s data repository. We abstracted patient characteristics (age, sex, race), discharge diagnoses, and disposition status. We identified patients with injury-related visits using the International Classification of Diseases – Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM). We classified patients as having experienced a trauma if they had an ICD9-CM code between 800–959, excluding those seen for late effects of injuries (ICD9-CM codes 905-909), foreign bodies (ICD9-CM codes 930-940), burns (ICD9-CM codes 940-950), or minor injuries, including isolated strains/sprains (ICD9-CM codes 840-849), superficial injuries (ICD9-CM codes 910-919), and contusions (ICD9-CM 920-924). We also excluded patients under age 18, and those who died in the ED. We used the discharge diagnoses to categorize co-morbidities, using the methodology of Elixhauser.10 We collapsed disposition status into three categories: transferred to a trauma center, admitted to the non-trauma center, or discharged.

We dichotomized patients’ injuries as minor or moderate to severe. Patients with moderate to severe injuries had either an Injury Severity Score [ISS]>15 or a ‘life-threatening’/‘critical’ injury, as per the ACS-COT.1 [Table 1] The ACS-COT recommends transferring these patients. We used a validated computer program to translate ICD9-CM diagnostic codes into ISS.5,11 We identified patients with ‘life-threatening’ or ‘critical’ injuries with an algorithm that we created based upon ICD9-CM codes. We validated our algorithm with a random sample of charts from 225 patient visits predicted to have such injuries and 225 patient visits predicted not to have them, comparing those predictions with a surgeon’s independent reviews of their charts. We modified the algorithm and repeated the process until we achieved 91% agreement (kappa = 0.8). Disagreements between the algorithm and chart review were most common with two specific injuries, amputations and spinal column fractures, which often appeared in medical record codes even when the injury was chronic, rather than acute. For example, a patient who presented with abrasions after falling out of a car was coded for traumatic amputation, even though that amputation had occurred much earlier. To avoid misclassification, we excluded patients with these two injuries from our analysis.

Table 1.

Algorithm used to select injuries described by the ACS

| Injuries the ACS-COT considers life-threatening or critical | ICD9-CM codes | Assumptions/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carotid or vertebral injuries | 900 | |

| Aorta or great vessel injuries | 901 | |

| Cardiac rupture | 861.0 and 861.1 |

|

| Bilateral pulmonary contusions with PaO2/FiO2 ratio<200 | - |

|

| Major abdominal vascular injury | 902 | |

| Grade IV or V liver injury with >6 units pRBC | 864.04 or 864.14 |

|

| Unstable pelvic fracture with >6 units pRBC | 808.43 or 808.53 |

|

| Fracture or dislocation with loss of distal pulses | 903.1 – 903.3 in conjunction with 812, 813, and 818 904.1-904.5 in conjunction with 821, 822, 823, 824, and 827 |

|

| Open skull fracture or penetrating injury | 800.5-800.9 801.5-801.9 803.5-803.9 804.5-804.9 |

|

| GCS<14 or lateralizing neurologic injury | 800-804 850.2-850.5 851-854 |

|

| Spinal cord deficit or lateralizing neurologic sign | 806 952-955.2 956-956.2 |

|

| Spinal column fractures | - |

|

| >2 unilateral rib fractures or bilateral rib fractures | 807.03-807.1 807.4-807.6 |

|

| Open long bone fracture | 812.1, 812.3, 812.5 813.1, 813.3, 813.5 820.1, 820.3, 820.5 821.1, 821.3, 821.5 823.1, 823.3, 823.5 824.1, 824.3, 824.5 |

|

| Significant torso injury with advanced co- morbid disease | 860.1, 860.3, 860.5 861.2-861.9 862-870 |

|

Analysis

We compared the demographic and injury characteristics of patients with minor and moderate to severe injuries, and of patients transferred, admitted and discharged using Student’s t-test, chi-square, and ANOVA. We calculated rates of under-triage and over-triage as defined by the ACS-COT.1

To assess physician-level practice variation, we summarized the median (interquartile range) caseload of each physician standardized by year, categorized the frequency of types of injuries seen, and calculated physician-specific rates of under- and over-triage. We compared performance with the ACS-COT triage benchmarks of ≤5% under-triage and ≤50% over-triage.1

We estimated the correlation between physician demographic characteristics (sex, years of experience, board certification, ATLS certification) and physician-specific rates of under- and over-triage using the non-parametric Spearman correlation coefficient or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. We estimated the correlation between physicians’ caseload of patients with moderate to severe injuries and physician-specific rates of under- and over-triage using the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Human Subjects

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board study reviewed and approved the study as meeting the federal exemption for written informed consent.

RESULTS

Physician and hospital

We recruited 29/50 (58%) of the physicians who staff the EDs of the eight community hospitals in our study. Their mean age was 47.6 years (SD = 8.9); they had completed residency a mean of 16.8 (SD=10.1) years prior to study enrollment; 21 (72%) were board-certified in Emergency Medicine; 20 (69%) were certified in ATLS. The eight non-trauma centers were primarily non-teaching hospitals, with a mean of 300 beds and 24,175 ED visits a year. [Table 2]

Table 2.

Physician characteristics

| Variable | Physicians n=29 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.6 (8.9) |

|

| |

| Sex, n(%) | |

| Male | 20 (69) |

| Female | 9 (32) |

|

| |

| Race, n(%) | |

| Caucasian or white | 23 (79) |

| Asian | 6 (21) |

|

| |

| Primary specialty, n(%) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 21 (72) |

| Internal Medicine | 6 (21) |

| Family Practice | 2 (7) |

|

| |

| Years since completing residency, mean (SD) | 16.8 (10.1) |

|

| |

| ATLS certified, n(%) | |

| Yes | 20 (69) |

| No | 9 (32) |

|

| |

| Hospitals at which physicians work | |

| Bed count, mean (SD) | 300 (88) |

| Total admissions, mean (SD)* | 14,347 (10,580) |

| Total ED visits, mean (SD)* | 24,175 (12,238) |

| Distance to a trauma center, mean miles (SD) | 16 (29) |

| Teaching status of hospital, n(%) | |

| No teaching | 3 (37) |

| Minor teaching | 3 (37) |

| Major teaching | 2 (25) |

Patient characteristics

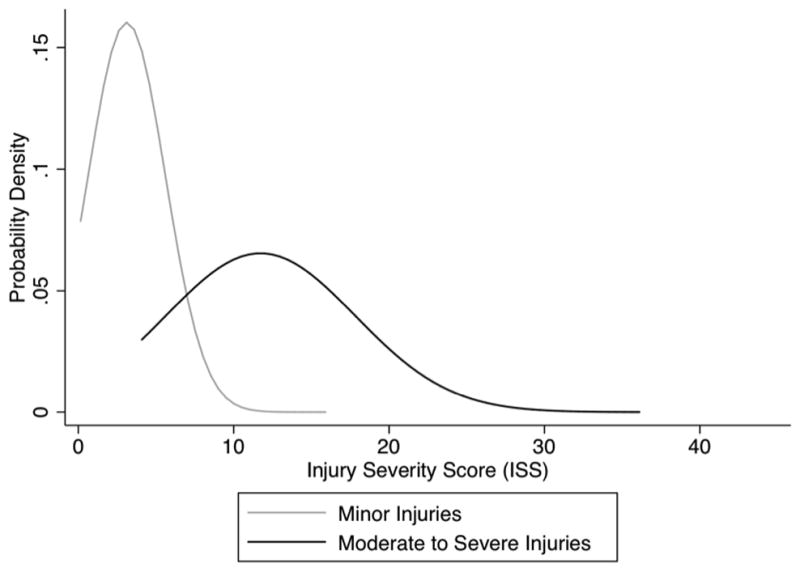

We identified 337,600 billing records for these 29 physicians over the four-year period. We matched 251,410 (74%) of the billing records with a hospital medical record discharge abstract. 66,824 (27%) had a primary diagnosis of trauma, of which 17,316 (26%) met study inclusion criteria. [Figure 1] Only 277 patients (2%) had moderate to severe injuries. Among all 17,316 patients, 557 (3%) were transferred to a trauma center.

Figure 1.

Sample selection

Patients seen by 29 participating physicians at 8 non-trauma centers between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010.

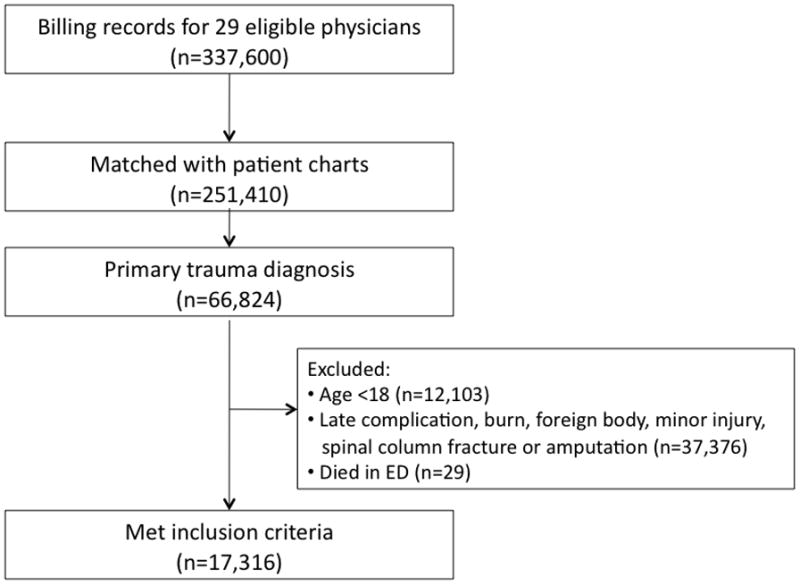

Patients with moderate to severe injuries were older, more likely to be men, and more likely to have co-morbid conditions than patients with minor injuries. The mean ISS among patients with moderate to severe injuries was 11.7 (range 1–43, SD 6.1) and 3.1 among patients with minor injuries (range 1–14, SD 2.5). [Figure 2] The most common moderate to severe injuries were multiple rib fractures (53%) and traumatic brain injuries (12%). The least common were skull fractures (2%) and unstable pelvic fractures (0.7%).

Figure 2.

Probability density distribution of ISS for patients with minor and moderate to severe injuries. The mean ISS of patients with minor injuries was 3.1 (SD 2.49) and the mean ISS of patients with moderate to severe injuries was 11.7 (SD 6.1). This figure demonstrates the overlap that occurs in the presentation of patients with injuries defined by the ACS-COT as being minor or moderate to severe.

Among patients classified with moderate to severe injuries, 104 (38%) were discharged home, 108 (39%) were admitted to non-trauma centers, and 65 (23%) were transferred to the trauma center. The under-triage rate, or the proportion of patients with moderate to severe injuries who were not transferred to a trauma center, was 77%. Patients who were transferred had a different injury complex than patients not transferred. They had higher rates of head or abdominal injuries. In contrast, patients admitted to non-trauma centers had higher rates of extremity injuries, while those discharged home had higher rates of chest injuries. The mean ISS was higher among patients transferred than patients admitted or discharged home (13.6 v. 12.2 v. 9.6, p<0.01). Patients most likely to be transferred had open skull fractures and significant torso injuries. Patients admitted or discharged were most likely to have rib fractures and traumatic brain injuries. [Table 3]

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Patients with minor injuries | Patients with moderate to severe injuries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged n=14,750 | Admitted n=1,797 | Transferred n=492 | p value | Discharged n=104 | Admitted n=108 | Transferred n=65 | p value | |

| Age, n (%) | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | ||||||

| 18–24 | 2,023 (14) | 40 (2) | 56 (11) | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | ||

| 25–44 | 5,451 (37) | 123 (7) | 135 (27) | 25 (24) | 10 (9) | 21 (32) | ||

| 45–64 | 4,672 (32) | 295 (16) | 118 (24) | 36 (35) | 23 (21) | 17 (26) | ||

| 65–74 | 1,011 (7) | 200 (11) | 52 (11) | 12 (12) | 20 (19) | 4 (6) | ||

| 75+ | 1,593 (11) | 1,139 (63) | 131 (27) | 24 (23) | 55 (51) | 21 (32) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Female, n(%) | 6,719 (46) | 1,285 (72) | 185 (38) | p<0.01 | 36 (35) | 54 (50) | 28 (43) | p=0.08 |

|

| ||||||||

| Race | p<0.01 | p=0.21 | ||||||

| White | 12,904 (87) | 1,686 (94) | 424 (86) | 98 (94) | 100 (93) | 58 (89) | ||

| Black | 1,523 (10) | 83 (5) | 62 (13) | 6 (6) | 7(6) | 5 (8) | ||

| Asian | 79 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hispanic | 28 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other/unknown | 216 (1) | 22 (1) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Co-morbidities (selected), n(%) | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | ||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 157 (1) | 238 (13) | 16 (3) | 2 (2) | 16 (15) | 3 (5) | ||

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 224 (2) | 366 (20) | 29 (6) | 3 (3) | 21 (19) | 4 (6) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 68 (0.5) | 125 (7) | 8 (2) | 0 (0) | 12 (11) | 1 (2) | ||

| Hypertension (combined) | 2,303 (16) | 936 (52) | 114 (23) | 26 (25) | 61 (56) | 19 (29) | ||

| Paralysis | 22 (0.2) | 29 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 553 (4) | 161 (9) | 18 (4) | 2 (2) | 18 (17) | 2 (3) | ||

| Diabetes (combined) | 840 (6) | 383 (21) | 41 (8) | 6 (6) | 29 (27) | 13 (18) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 512 (3) | 350 (19) | 18 (4) | 3 (3) | 21 (19) | 3 (5) | ||

| Renal failure | 55 (0.4) | 176 (10) | 11 (2) | 1 (1) | 10 (9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Psychoses | 208 (1) | 67 (4) | 11 (2) | 0 (0) | 6 (6) | 1 (2) | ||

| Depression | 600 (4) | 333 (19) | 24 (5) | 6 (6) | 17 (16) | 5 (8) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Nature of Injuries, n(%) | p<0.01 | p=0.03 | ||||||

| Fracture | 5,403 (31) | 1,788 (75) | 280 (38) | 87 (56) | 114 (58) | 67 (52) | ||

| Dislocation | 489 (3) | 52 (2) | 20 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Sprain/strain | 577 (3) | 22 (1) | 10 (1) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Internal organ | 358 (2) | 130 (5) | 126 (17) | 29 (19) | 47 (24) | 37 (28) | ||

| Open wound | 9,051 (52) | 230 (10) | 206 (28) | 12 (8) | 9 (5) | 16 (12) | ||

| Amputation | 51 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | 23 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Blood vessel | 4 (0.02) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Superficial/contusion | 1,142 (7) | 139 (6) | 57 (8) | 13 (8) | 18 (9) | 7 (5) | ||

| Crush | 209 (1) | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Nerve | 9 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) | 9 (6) | 5 (3) | 1 (0.8) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Body region affected by injuries, n(%) | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | ||||||

| Head | 405 (2) | 111 (5) | 148 (20) | 23 (15) | 23 (12) | 25 (19) | ||

| Face | 388 (2) | 40 (2) | 38 (5) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | ||

| Chest | 700 (4) | 140 (6) | 39 (5) | 80 (51) | 81 (41) | 47 (36) | ||

| Abdomen | 190 (1) | 87 (4) | 34 (5) | 4 (3) | 17 (9) | 16 (12) | ||

| Extremities | 6,798 (39) | 1,669 (70) | 257 (35) | 21 (13) | 47 (24) | 18 (16) | ||

| External | 8,812 (51) | 329 (14) | 218 (30) | 24 (15) | 27 (14) | 21 (16) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Injuries meeting criteria for transfer (selected), n(%) | p<0.01 | |||||||

| Unstable pelvis fracture | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2) | ||

| Open skull fracture | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (6) | ||

| GCS<14 | - | - | - | 17 (16) | 10 (9) | 7 (11) | ||

| Spinal cord deficit | - | - | - | 9 (9) | 7 (6) | 3 (5) | ||

| >2 rib fractures | - | - | - | 67 (64) | 55 (51) | 26 (40) | ||

| Open long bone fractures | - | - | - | 7 (7) | 11 (10) | 8 (12) | ||

| Significant torso injury | - | - | - | 3 (3) | 17 (16) | 14 (22) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Injury Severity Score, mean(SD) | 2.6 (1.9) | 6.9 (3.0) | 5.4 (3.3) | p<0.01 | 9.6 (4.8) | 12.2 (5.6) | 13.6 (6.6) | p<0.01 |

Among patients classified with minor injuries, 14,750 (87%) were discharged home, 1,797 (11%) were admitted to non-trauma centers, and 492 (3%) were transferred to the trauma center. The mean over-triage rate, or the proportion of patients transferred with minor injuries, was 88%. Patients transferred to trauma centers were younger, more likely to be men, and less likely to have co-morbidities than patients admitted to non-trauma centers (p<0.01). The mean ISS was lower among patients transferred than among those admitted, but higher than among patients discharged home (5.4 v. 6.9 v. 2.6, p<0.01). Patients transferred were most likely to have head injuries. [Table 3]

Physician caseload, and triage patterns

Study physicians each evaluated a median of 2,423 patients (inter-quartile range [IQR] 1637–3030) a year, of whom 148 (IQR 92–246) were trauma patients who met inclusion criteria. Physicians saw a median of 3 patients (IQR 1–4) with moderate to severe injuries each year. One physician never saw a patient with moderate to severe injuries. One physician never transferred a patient to a trauma center. [Table 4]

Table 4.

Physician caseload standardized by year

| Variable | Physicians n=29 |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients, median (IQR) | 2423 (1637 – 3030) |

| Total number of patients with an injury-related visit, median (IQR) | 463 ( 293 – 713) |

| Total number of trauma patients meeting inclusion criteria, median (IQR) | 148 (92 – 246) |

| Total number of trauma patients with moderate-severe injuries, median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) |

Among physicians who saw at least one patient with moderate to severe injuries, the median under-triage rate was 80% (IQR 71–100%); the median over-triage rate was 91% (IQR 83–98%). None of the physicians met ACS-COT performance benchmarks.

We found no correlation between physician characteristics, including whether they had ATLS certification, and rates of under- and over-triage. However, the annual volume of patients with moderate to severe injuries seen by each physician was inversely associated with rates of under-triage (Spearman correlation coefficient −0.42, p=0.03) and rates of over-triage (correlation coefficient −0.45, p=0.02). Physicians in the highest quartile, who saw between 5 to 6 patients with moderate to severe injuries a year, under-triaged fewer patients compared with physicians in the lowest quartile, who saw 1 patient with moderate to severe injuries (69% v. 100%), and over-triaged more patients (84% v. 91%). Thus, those with more experience adhered to the guidelines more closely.

DISCUSSION

In an analysis of a cohort of trauma patients who presented initially to the EDs of non-trauma centers in western Pennsylvania, we found physician-level variability in triage rates. By analyzing practice variation, we identified several potential explanations for physicians’ performance. First, as in other clinical contexts, a relationship existed between volume and outcome.12–14 Physicians with greater experience with trauma patients were more likely to follow the ACS-COT guidelines for the triage of patients. Second, significant overlap existed between the distributions of patients who did and did not meet guidelines for transfer. Guideline adherence would have required complex and subtle discrimination among patients.

Up to 50% of all injured patients receive some treatment at non-trauma centers.15 Multiple epidemiological studies document rates of under-triage of 30–40% among all patients with moderate to severe injuries, and rates as high as 70% among patients taken initially to non-trauma centers.4, 5 Our work replicates the results from these studies, and expands on them by characterizing the variability in physician performance, and examining potential correlates, that may explain triage rates. One possible explanation for variability in physician performance is that volume influences outcomes. Physicians who treated a greater number of patients with moderate to severe injuries were more likely to triage them in accordance with clinical practice guidelines. That result echoes studies in cancer, coronary artery disease, and critical care where greater experience translates into better outcomes.12–14 The correlation emerged despite the limited variance in the number of moderate to severe injuries patients seen by individual physicians in this sample (IQR 1–4). Thus, even a moderate increase in volume was associated with better performance.

A second explanation is that the task of triage is more complex than previously recognized. The ACS-COT has attempted to standardize physician decision making by establishing explicit criteria for the transfer of patients to trauma centers, identifying specific injuries and a threshold of injury severity (ISS >15) that warrant transfer.1 In other words, they assume that physicians can easily distinguish between patients with minor and moderate to severe injuries. However, an analysis of the incidence and epidemiology of injury at non-trauma centers indicates the challenge of the task required of ED physicians attempting to apply them. Patient volumes at non-trauma centers preclude physicians from obtaining significant experience triaging patients with moderate to severe injuries. In the present study, only 1 out of 50 patients presenting after trauma and 1 out of 1000 patients presenting overall had an injury that met guidelines for transfer. Moreover, patients who met the guidelines had a mean ISS of 12, lower than the ACS-COT cutpoint for patients that warrant transfer regardless of their specific injuries. In practice, such a patient would have had only one moderate injury, such as a small subdural hemorrhage, and one minor injury, such as an isolated rib fracture. This may contribute to our observation that physicians discharged home 1/3 of patients the ACS-COT would classify as having moderate to severe injuries. As seen in Figure 2, significant overlap existed between the injury severity distributions of patients who did and did not meet guidelines for transfer. Adherence to the guidelines therefore requires that physicians make potentially challenging diagnostic distinctions under conditions of time-pressure and uncertainty.

We speculate that physicians compensate for the complexity of decision making by relying on their heuristics, intuitive judgments, rather than the clinical practice guidelines to determine what qualifies as a severe injury. This would explain our finding of an association between injury type and triage patterns. For example, physicians were more likely to transfer patients with skull fractures to trauma centers than those with rib fractures. In other words, some kinds of cases intuitively seem better or worse than they actually are. Physicians with even modestly greater experience with trauma patients (in terms of absolute number) had better clinical judgment. However, given the low base rate of severe injuries, physicians lacked the practice and feedback necessary to appropriately calibrate their heuristics.16 Consequently, use of these cognitive processes typically resulted in high rates of non-compliance with clinical practice guidelines.

One might also speculate that physicians consciously choose to deviate from the guidelines when they believe that the guidelines are not valid. We did not explore the relationship between triage decisions and clinical outcomes – nor were we powered to do so – and therefore cannot shed light on the question of whether physician decisions were clinically appropriate (e.g., not harmful).

This study has important implications for quality improvement interventions in trauma. The persistence of under-triage despite systematic quality improvement efforts suggests that existing interventions have failed to modify key determinants of triage. Our results demonstrate the influence of physician clinical judgment on triage patterns. Although up to of all trauma patients receive care at non-trauma centers, most physicians who treat patients have little if any experience triaging the severely injured. Currently, the only program that targets physician decision making is ATLS. However, the persistence of under-triage suggests that this training model is insufficient. If experience, heuristics and attitudes do influence decision making, then physicians either need training dedicated to overcoming their biases or a work environment that is less vulnerable to them (e.g., by structuring choices in a way that force physicians to default to the desired strategy).17

Our study had several limitations. First, we used the ACS-COT inter-facility triage guidelines as the reference standard against which we evaluated physician decision making. Although robust observational data supports the underlying principle that severely injured patients have better outcomes when treated at trauma centers,18 the validity of the specific guidelines remains unclear. Failures of compliance may therefore have variable clinical consequences. Nonetheless, the widespread dissemination of the guidelines have made them the de-facto standard for physician decision making. Consequently, better understanding of patterns of compliance can provide valuable insights into physician decision making in trauma triage. Second, we merged billing records with patient charts in order to identify all relevant clinical encounters, losing 25% of cases due to the lack of a common identifier. However, we have no reason to believe that the missing patients occurred systematically, which should limit the introduction of bias into our results. Third, we relied on ICD9-CM codes to identify patients who did and did not meet guidelines for transfer. Although the use of discharge diagnosis codes to assign injury severity is well accepted, if these discharge codes did not capture patients’ clinical presentation, we may have underestimated physicians’ performance.11,18 We believe that our analyses were improved by confirmation of the reliability of the algorithm we used to stratify injury severity through an electronic chart review. We also excluded injuries with ICD9-CM codes (i.e. spinal column fractures and amputations), which we found consistently conflated acute and chronic events. The exclusion of these injuries reduced the chances of mis-specification, and should have had little effect on the estimated rates of under-triage, since we assume the proportion of patients transferred with these injuries would be similar to patients with other types of moderate to severe injuries.

Our study was also limited by studying a small sample of physicians, meaning that we had sufficient power to detect only large associations between physician characteristics and triage decisions.19 We also could not model the effect of non-physician variables on under-triage. In order to characterize performance within a single health system, with shared institutional constraints, we drew all our physicians working in a single trauma system. It is, however, a system that has had a regionalized system in place for over twenty years, meeting all the regulatory criteria set by the ACS-COT. It has three Level I trauma centers, an aero-medical transport service, an extensive outreach program intended to improve physicians’ transfer decisions, and is routinely assessed by the state trauma foundation.20 Thus, it should have relatively high levels of performance most confidently generalized to other states with similar rates of regionalization.4,5 Additionally, rates of both overall and moderate to severe trauma in our cohort match national statistics for injury-related ED visits and the epidemiology of trauma, further supporting the generalizability of our observations.21,22

In conclusion, we found variability in physician triage practices for trauma patients, suggesting that clinical judgment influences decision making. Physician performed better when they had more exposure to patients with severe injuries and to some classes of trauma. Further research is needed into how both factors affect performance, so that interventions can be created that afford physicians the diagnostic skills needed to take full advantage of their other abilities.

Footnotes

Level of evidence and study type: Level III; epidemiological

Author contributions: Dr. Mohan had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Mohan, Barnato, Rosengart, Farris, Fischhoff, Angus, Yealy, Switzer

Acquisition of data: Mohan, Saul

Analysis and interpretation of data: Mohan, Rosengart, Farris, Fischhoff, Angus, Barnato, Yealy, Switzer, Saul

Drafting of the manuscript: Mohan

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Rosengart, Farris, Fischhoff, Angus, Barnato, Yealy, Switzer, Saul

Statistical analysis: Mohan

Obtained funding: Mohan

Administrative, technical, or material support: Mohan, Angus

References

- 1.Committee on Trauma – American College of Surgeons. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Science. Hospital based emergency care at the breaking point. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Model trauma system planning and evaluation. 2006 Feb; Retrieved from: https://www.socialtext.net/acs-demo-wiki/index.cgi?regional_trauma_systems_optimal_elements_integration_and_assessment_systems_consultation_guide.

- 4.Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP. A resource-based assessment of trauma care in the United States. J Trauma. 2004;56 (1):173–178. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000056159.65396.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohan D, Rosengart MR, Farris C, et al. Assessing the feasibility of the American College of Surgeons’ benchmarks for the triage of trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2011;146:786–792. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60(2):371–78. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197916.99629.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branas CC, MacKenzie EJ, Williams JC, et al. Access to trauma centers in the United States. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2626–2633. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang DC, Bass RR, Cornwell EE, MacKenzie EJ. Undertriage of elderly trauma patients to state-designated trauma centers. Arch Surg. 2008;143(8):776–781. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.8.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macias CA, Rosengart MR, Puyana JC, et al. The effects of trauma center care, admission volume, and surgical volume on paralysis after traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):10–17. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris RD, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses: validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27(4):412–422. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grumbach K, Anderson GM, Luft HS, et al. Regionalization of cardiac surgery in the United States and Canada. Geographic access, choice, and outcomes. JAMA. 1995;274(16):1282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, et al. Effect of hospital volume on inhospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125(3):250–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, et al. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. NEJM. 2006;355(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas B, Stukel TA, Gomez D, et al. The mortality benefit of direct trauma center transport in a regional trauma system: a population-based analysis. J Trauma. 2012;72(6):1510–1517. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318252510a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahneman D, Klein G. Conditions for intuitive expertise: a failure to disagree. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):515–526. doi: 10.1037/a0016755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klayman J, Brown K. Debias the environment instead of the judge: an alternative approach to reducing error in diagnostic (and other) judgment. Cognition. 1993;49:97–122. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(93)90037-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. NEJM. 2006;354(4):366–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen J. Quantitative methods in psychology: a power primer. Psych Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peitzman AB, Courcoulas AP, Stinson C, et al. Trauma center maturation: quantification of process and outcome. Ann Surg. 1999;230(1):87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkelstein EA, Corso PS, Miller TR, et al. The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Office of Information Services – Centers for Disease Control. Emergency department visits. (5/16/12) Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ervisits.htm.