Abstract

Purpose

To compare correlations of intramyocellular lipids (IMCL) measured by short and long echo-time proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) with indices of body composition and insulin resistance in obese and normal-weight women.

Materials and Methods

We quantified IMCL of tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus (SOL) muscles in 52 premenopausal women (37 obese and 15 normal weight) using single-voxel 1H-MRS PRESS at 3.0 T with short (30 msec) and long (144 msec) echo times. Statistical analyses were performed to determine correlations of IMCL with body composition as determined by computed tomography (CT) and insulin resistance indices and to compare correlation coefficients from short and long echo-time data. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), linewidth, and coefficients of variation (CV) of short and long echo-time spectra were calculated.

Results

Short and long echo-time IMCL from TA and SOL significantly correlated with body mass index (BMI) and abdominal fat depots (r = 0.32 to 0.70, P = <0.05), liver density (r = −0.39 to −0.50, P < 0.05), and glucose area under the curve as a measure of insulin resistance (r = 0.47 to 0.49, P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between correlation coefficients of short and long echo-time spectra (P > 0.5). Short echo-time IMCL in both muscles showed significantly higher SNR (P < 0.0001) and lower CVs when compared to long echo-time acquisitions. Linewidth measures were not significantly different between groups.

Conclusion

IMCL quantification using short and long echo-time 1H-MRS at 3.0 T is useful to detect differences in muscle lipid content in obese and normal-weight subjects. In addition, IMCL correlates with body composition and markers of insulin resistance in this population with no significant difference in correlations between short and long echo-times. Short echo-time IMCL quantification of TA and SOL muscles at 3.0 T was superior to long echo-time due to better SNR and better reproducibility.

Keywords: IMCL, 1H-MR spectroscopy, echo-time, obesity

SKELETAL MUSCLE is an important regulator of insulin homeostasis and accumulation of intramyocellular lipids (IMCL) is strongly associated with measures of insulin resistance (1,2). IMCL are increased in obesity and play an etiologic role in obesity-induced insulin resistance (1–5). IMCL content has been found to be a better predictor of insulin resistance than either body mass index (BMI) or plasma free fatty acids (FFA) among normal weight, obese, and diabetic men and women with sedentary or modestly active lifestyles (2,6). Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) is an accurate noninvasive technique to quantify IMCL in vivo and can successfully quantify IMCL in conditions associated with insulin resistance such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and HIV-lipodystrophy (1,3,5,7,8).

In most studies using 1H-MRS for IMCL quantification, acquisitions were performed using short echotimes between 10 and 50 msec, and the methylene signal at 1.3 ppm was referenced to water or creatine for IMCL quantification (2,8–10). The use of short echo-times helps minimizing the effect of T2 relaxation changes and yields higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). However, recent studies have suggested that muscle lipid peaks are better separated using long echo-times between 135 and 270 msec (7,11,12), which could benefit quantification of neighboring resonances frequently overlapped at shorter echo-times, such as the methyl (0.9 and 1.1 ppm) and methylene (1.3 and 1.5 ppm) lipid peaks. Furthermore, while most studies on IMCL have performed 1H-MRS at 1.5 T (1,5–7,9), improved spectral quality with better SNR and better peak separation have been reported at 3.0 T (3,10,13,14). Skoch et al (12) performed muscle 1H-MRS to determine IMCL using an echo-time of 240 msec at 3.0 T showing reliable separation of methyl and methylene lipid resonances.

Although long echo-times at 3.0 T may enhance IMCL and overall lipid quantification, the effect of this improvement on correlations with body composition and insulin sensitivity indices remains unknown. The purpose of our study was to compare correlations between short and long echo-time 1H-MRS IMCL acquisitions at 3.0 T with body composition and insulin sensitivity indices in obese women and normal-weight controls. Furthermore, we sought to compare spectral separation, SNR, linewidth, and reproducibility of IMCL quantification of tibialis anterior (TA) and soleus (SOL) muscles using short and long echo-times at 3.0 T.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to the study. The study group was comprised of 52 healthy premenopausal women who were part of a clinical obesity trial. Subjects were considered overweight/obese when BMI was >25 kg/m2 and normal weight when BMI was between 18–25 kg/m2. There were 37 obese subjects (BMI: 34.3 ± 5.1 kg/m2) and 15 normal-weight controls (BMI: 21.8 ± 2.1 kg/m2). Exclusion criteria for the study were pregnancy, presence of a pacemaker or metallic implant, weight greater than 200 kg, claustrophobia, diabetes mellitus or other chronic illness, estrogen or glucocorticoid use. Short echo-time 1H-MRS IMCL data, body composition, and clinical characteristics have been previously reported in 38 of the 52 subjects (3).

A separate reproducibility study was performed in three subjects (two males, one female, mean age: 32 ± 6 years) who underwent short and long echo-time 1H-MRS of TA and SOL muscles after an 8-hour overnight fast before and after repositioning in the MR scanner. One of the volunteers was overweight (BMI: 27 kg/m2) and the other two volunteers were of normal weight (mean BMI: 20 ± 1.4 kg/m2). All participants of the clinical obesity trial (normal weight and obese subjects) were admitted to the Clinical Research Center, where testing was performed. Subjects underwent standard oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with 75 g glucose load. Glucose area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from glucose levels obtained before the test and every 30 minutes for a period of 2 hours (13).

1H-MRS of Muscle

1H-MRS was performed using a 3.0 T (Siemens Trio; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) MRI system after an 8-hour overnight fast. Subjects were asked to avoid moderate physical activity, vigorous exercise, or high-fat diet 72 hours prior to scanning. Subjects were positioned feet-first in the magnet bore and the right calf was placed in a commercially available transmit/receive quadrature extremity coil, with 18-cm diameter (USA Instruments, Aurora, OH). A triplane gradient echo localizer pulse sequence with repetition time (TR) of 15 msec and echo-time (TE) of 5 msec was obtained. Axial T1-weighted images (TR, 400 msec; TE, 11 msec; slice thickness, 4 mm; inter-slice gap, 1 mm; matrix, 512; NEX, 1; FOV 22 cm) of the proximal two-thirds of the calf were prescribed. The first slice was placed at the level of the fibular tip and the prescription stack was propagated distally. In all cases a voxel measuring 15 × 15 × 15 mm (3.4 mL) was placed on the axial T1-weighted slice with largest muscle cross-sectional area by visual inspection of the TA and subsequently the SOL muscle, avoiding visible interstitial tissue, fat, or vessels. Single-voxel 1H-MRS data were acquired using first a short echo-time (30 msec) and subsequently long echo-time (144 msec) point-resolved spatially localized spectroscopy (PRESS) pulse sequence with a TR of 3000 msec, 64 acquisitions, 1024 data points, and receiver bandwidth of 1000 Hz. The short and long echo-time PRESS acquisitions each lasted 3 minutes and 24 seconds. Water suppression was used for metabolite acquisition and unsuppressed water spectra of the same voxel were obtained for each scan with the same parameters as the metabolite acquisition except for the use of eight acquisitions (total duration, 36 seconds). For each voxel placement, automated optimization of gradient shimming, water suppression, and transmit-receive gain were performed, followed by manual adjustment of gradient shimming targeting water linewidths of 12–14 Hz. Metabolite and unsuppressed water levels were not corrected for T1 and T2 relaxation times. Total imaging time was ≈30 minutes for each subject. In order to ensure consistent positioning for the reproducibility study, the same axial slice was used for voxel placement (counted from the proximal fibular tip).

1H-MRS Data Analysis

Fitting of all 1H-MRS data was performed using LCModel (v. 6.1-4A, Stephen Provencher, Oakville, ON, Canada) (14). Data were transferred from the MR scanner to a Linux workstation and metabolite quantification was performed using eddy current correction and water scaling. The fitting algorithm was customized for muscle analysis providing estimates for lipid peaks (0.9, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 2.1, and 2.3 ppm), creatine (2.8 and ≈3.0 ppm), trimethylamines (3.2 ppm), and putative taurine signal (≈3.5 ppm). Data for IMCL (1.3 ppm) and EMCL (1.5 ppm) methylene protons were used for statistical analyses. LCModel IMCL and EMCL estimates were automatically scaled to unsuppressed water peak (4.7 ppm).

Conversion of IMCL concentrations into millimoles per kg wet weight was performed using the algorithm recently described by Weis et al (15). Concentrationsof EMCLCH2 and IMCLCH2 were computed as millimoles per liter of muscle tissue and were corrected for T1 and T2 relaxation effects of the unsuppressed water peak using LCModel’s control parameter ATTH2O, which was adjusted for short and long echo-times using the following formula: exp(–TE/T2) [1–exp(–TR/T1)] (16) employing T1 and T2 values of water at 3.0 T (17). This value was divided by factor of 31 assuming that the average number of methylene protons is 62 per triglyceride molecule, equivalent to 31 CH2 groups (15). The resulting concentration was then corrected for relaxation effects of IMCLCH2 using the previous water correction formula employing T1 and T2 values of IMCL at 3.0 T adjusted for short and long echo-times. This value was then divided by the tissue density of 1.05 kg/L for normal muscle tissue to convert millimoles per liter of muscle tissue to millimoles per kg wet weight (15). The jMRUI software package (A. van den Boogaart, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) (18) was used for measurement of linewidths (full width half maximum, FWHM) and SNR of unsuppressed water peak, analyzing each time domain directly from free induction decays (FIDs). FWHM was calculated automatically using the Hankel-Lanczos single-variable decomposition (HLSVD) fitting algorithm. SNR was determined by the ratio between maximal unsuppressed water amplitude at 4.7 ppm measured by HLSVD and noise root mean square (standard deviation) extracted from the final 10% of FID (102 data points). Figures were generated using iNMR software (v. 3.2.2, Mestrelab Research, http://www.inmr.net).

Body Composition Measurement

Each subject underwent cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra and a single slice of the upper abdomen encompassing the liver (LightSpeed, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). Scan parameters for each image were: 80 kV, 70 mA, 2 seconds gantry rotation, 1 cm slice thickness, 48 cm FOV. Fat attenuation coefficients were set at −50 to −250 HU as described by Borkan et al (19). For the single slice through the abdomen, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) areas and total adipose tissue (TAT, the sum of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue) areas were determined based on offline analysis of tracings obtained utilizing commercial software (VITRAK, Merge/eFilm, Milwaukee, WI; and Alice v. 4.3.9, Parexel, Waltham, MA). To assess hepatic fat content, the attenuation of the liver was determined within a circular region of interest placed in the dorsal aspect of the organ. Attempts were made to avoid vessels, artifacts, and other areas of inhomogeneity. Hepatic fat content was studied as the liver attenuation absolute value.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP (v. 5.0.1a, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) software. All results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). IMCL, body composition, and glucose-AUC were compared between obese subjects and normal-weight controls using Student’s t-test and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to control for age as IMCLSOL have been found to be higher in older subjects (20). In order to determine whether data obtained at long echo-times showed different associations of IMCL with measures of insulin resistance and body composition, linear regression analysis between IMCL from short and long echo-time spectra and glucose AUC and body composition were performed. We performed multivariate standard least squares regression modeling to control for age. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients of short and long echo-time spectra were compared by applying Fisher’s z-transformation and then the large sample z-test for independent samples. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Comparison of IMCL, EMCL, unsuppressed water peak, SNR, and FWHM between short and long echo-time 1H-MRS was performed using Student’s t-test. CVs were used to assess interscan variability of short and long echo-time 1H-MRS techniques.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics of Study Subjects

Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. The age of study participants ranged from 19–45 years, with a mean of 33.5 ± 7.4 years. Study participants ranged in BMI from 18.1–46.7 kg/m2, with a mean of 30.7 ± 7.2 kg/m2. Obese subjects were older and had higher glucose AUC compared to normal-weight controls, larger abdominal fat areas, increased liver fat manifested by lower liver density, and higher IMCL compared to normal-weight controls.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Obese Subjects and Normal-Weight Controls (Mean ± SD)

| Obese (n = 37) | Controls (n = 15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.9 ± 7.3 | 30.1 ± 6.8 | 0.03 |

| Weight (kg) | 91.9 ± 13.3 | 61.2 ± 9.0 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.3 ± 5.1 | 21.8 ± 2.1 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose-AUC (mg/dl/120 min) | 15947 ± 2977 | 12945 ± 1803 | 0.0007 |

| TAT (cm2) | 573.8 ± 170.6 | 214.9 ± 99.4 | <0.0001 |

| SAT (cm2) | 462.8 ± 145.0 | 183.6 ± 98.7 | <0.0001 |

| VAT (cm2) | 111.0 ± 55.5 | 31.2 ± 9.1 | <0.0001 |

| Liver density (HU) | 58.5 ± 11.6 | 64.0 ± 4.7 | 0.02 |

| IMCL-TA (TE30) (mmol/kg ww) | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.003 (0.0002*) |

| IMCL-TA (TE144) (mmol/kg ww) | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 0.004 (0.0002*) |

| IMCL-SOL (TE30) (mmol/kg ww) | 12.4 ± 5.8 | 6.6 ± 2.3 | <0.0001 (0.0003*) |

| IMCL-SOL (TE144) (mmol/kg ww) | 11.0 ± 5.7 | 5.5 ± 2.5 | <0.0001 (0.0004*) |

BMI, body mass index; AUC, area under the curve; TAT, total adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue, abdomen; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SC, subcutaneous; IMCL, intramyocellular lipids; TA, tibialis anterior muscle; SOL, soleus muscle; ww, wet weight.

P-value after controlling for age using ANCOVA.

1H-MR Spectroscopy

All spectra of TA (short and long echo-time) were analyzed and showed distinct IMCL and EMCL methylene resonances at 1.3 and 1.5 ppm, respectively (Fig. 1). Spectra of SOL muscle with indistinct IMCL methylene resonance due to overlapping lipid peaks were noted in one subject for short and in two different subjects for long echo-time acquisitions. These spectra were excluded from statistical analysis. The remaining SOL spectra showed well-defined separation of lipid peaks at 1.3 and 1.5 ppm characterized by a well-defined indentation between the peaks. Short and long echo-time TA and SOL IMCL were approximately two times higher in obese subjects compared to normal-weight controls (Table 1). Mean FWHM showed no significant difference between short and long echo-time 1H-MRS in both muscles. However, SNR values were significantly higher for short echo-time compared to long echo-time 1H-MRS (Table 2).

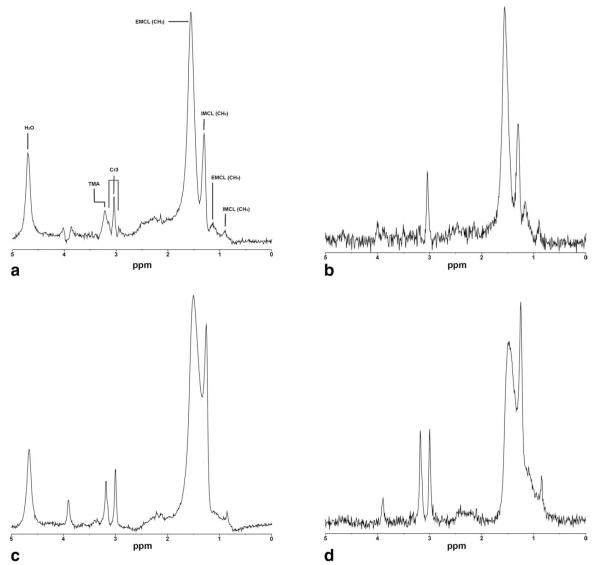

Figure 1.

1H-magnetic resonance metabolite spectra of tibialis anterior (A,B) and soleus (C,D) muscles obtained at 3.0 T from an obese subject (BMI: 30 kg/m2) using short (A,C) and long echo-times (B,D). Both short and long echo-time spectra demonstrate excellent separation of IMCL and EMCL methylene lipid peaks with increased SNR of short echo-time spectrum. IMCL, intramyocellular lipid methyl (CH3) and methylene (CH2) protons at 0.9 and 1.3 ppm; EMCL, extramyocellular lipid methyl (CH3) and methylene (CH2) protons at 1.1 and 1.5 ppm; Cr3, creatine CH3 resonances; TMA, trimethylammonium containing compounds at 3.2 ppm; H2O, residual water signal.

Table 2.

Mean SNR Amplitudes and FWHM of Unsuppressed Water Peak for Short and Long TE at 3.0 T

| TA |

SOL |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE 30 msec | TE 144 msec | P | TE 30 msec | TE 144 msec | P | |

| SNR | 339.3 ± 62.6 | 62.2 ± 18.8 | < 0.0001 | 353.7 ± 78.7 | 65.9 ± 20.2 | < 0.0001 |

| FWHM (Hz) | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 12.6 ± 2.0 | 0.2 | 13.3 ± 1.1 | 13.2 ± 3.3 | 0.8 |

TA, tibialis anterior muscle; TE, echo-time, SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; FWHM, full-width half maximum.

Reproducibility for short echo-time 1H-MRS was better compared to long echo-time acquisitions. CVs of short echo-time acquisitions were 8% and 6% for TA and SOL, respectively. CVs for long echo-time acquisitions were 18% and 19% for TA and SOL, respectively.

Association of Short and Long Echo-Time IMCL With Body Composition and Glucose AUC

There were strong correlations between short and long echo-time IMCL and body composition (weight, BMI, abdominal, and liver fat) and measures of insulin resistance (glucose AUC) (Table 3). After controlling for age, the associations remained significant (P < 0.05). No significant difference was seen when comparing correlation coefficients between short and long echo-time spectra using Fisher’s z-transformation and large sample z-test for independent samples (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlations of Short and Long Echo-Time IMCL Measures With Body Composition and Metabolic Parameters

| TA IMCL |

SOL IMCL |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE 30 msec |

TE 144 msec |

Fisher Z* | TE 30 msec |

TE 144 msec |

Fisher Z* | |||||

| r | P | r | P | P | r | P | r | P | P | |

| Weight | 0.44 | 0.001 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.5 | 0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | <0.0001 | 0.9 |

| BMI | 0.43 | 0.001 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.70 | <0.0001 | 0.67 | <0.0001 | 0.8 |

| TAT | 0.42 | 0.002 | 0.37 | 0.007 | 0.8 | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | 0.9 |

| SAT | 0.46 | 0.0007 | 0.38 | 0.006 | 0.6 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.9 |

| VAT | 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.48 | 0.0003 | 0.48 | 0.0004 | 1 |

| Liver density | −0.50 | 0.0002 | −0.39 | 0.004 | 0.5 | −0.49 | 0.0003 | −0.50 | 0.0002 | 0.9 |

| Glucose AUC | 0.47 | 0.0004 | 0.41 | 0.003 | 0.7 | 0.41 | 0.003 | 0.49 | 0.0004 | 0.6 |

TE, echo-time; BMI, body mass index; IMCL, intramyocellular lipids; TA, tibialis anterior muscle; BMI, body mass index; TAT, total adipose tissue; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue, abdomen; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; SC, subcutaneous; AUC, area under the curve.

Fisher z-transformation comparing correlation coefficients from short and long echo-times. P > 0.05 indicates no significant difference between correlations.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that IMCL from short and long echo-time 1H-MRS at 3.0 T had similar strong correlations with measures of body composition and insulin resistance. Both echo-time spectra demonstrated comparable linewidths while short echo-time spectra had ≈5 times higher SNR compared to long echo-time spectra. Furthermore, short echo-time spectra had better reproducibility.

Obesity is a known risk factor for the development of insulin resistance and a key component of the metabolic syndrome. Previous studies have shown that IMCL are increased in obesity and noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus and that IMCL quantified with 1H-MRS are reliable noninvasive surrogate markers of insulin sensitivity in individuals who are healthy, obese, or have type 2 diabetes (2,21). In addition, it has been hypothesized that increased IMCL plays an etiologic role in the development of insulin resistance (22). While most studies using 1H-MRS for IMCL quantifications used short echo-times, some studies have suggested that long echo-times might improve spectral separation (11,12) and have found positive correlations between IMCL obtained at long echo-times with measures of body composition in healthy males (7). Skoch et al (12) performed long echo-time 1H-MRS of TA at 1.5 T with reliable separation of methylene and methyl lipid components. Schick et al (23) compared short and long echo-time 1H-MRS for IMCL quantification at 1.5 T and observed that long echo-time (>200 msec) spectra resulted in improved resolution of lipid peaks compared to short echo-time (50 msec) spectra. However, no study performed short and long echo-time 1H-MRS at 3.0 T to compare spectral quality and association with markers of body composition and insulin resistance. In our study, there were no significant differences in correlation coefficients between short and long echo-time spectra of IMCL and measures of insulin resistance and body composition.

IMCL-SOL correlated better with measures of body composition than IMCL-TA. This may be secondary to the higher concentrations of IMCL and more insulin sensitive Type 1 fibers within the SOL compared to TA (21).

Using higher field strengths for quantification of IMCL has the advantage of higher SNR and improved chemical shift dispersion, increasing measurement precision (9,12). Skoch et al (12) demonstrated improved repeatability of IMCL measurements at 3.0 T compared to 1.5 T. In another study, no improvement in measurement precision of 1H-MRS for IMCL at 3.0 T compared to 1.5 T was noted (9). This may have been due to the fact that gains in spectral resolution were offset by FWHM broadening coupled with lower than expected increase in SNR at 3.0 T, and that only automated prescan shimming was performed without specific manual adjustments targeting specific linewidth (9).

In our study we performed manual shimming in order to obtain water linewidths of 12–14 Hz for short and long echo-time spectra. For both echo-times we obtained excellent peak separation for TA and SOL muscle in all but three cases. Using long echo-times did not improve peak separation, nor did it significantly affect association with measures of insulin resistance or body composition in both muscles. Furthermore, short echo-time spectra had better reproducibility than long echo-time spectra for both TA and SOL muscles. Additional shortcomings of long echo-time 1H-MRS are the relatively low SNR and the strong influence of T2 relaxation.

Our study had several limitations. We performed correction for T1 and T2 relaxation effects using values from the literature at 3.0 T (17) and did not measure T1 and T2 relaxation times that might lead to higher accuracy in metabolite concentration measurements, especially for long echo-time acquisitions that suffer more from the effects of T2 relaxation changes. However, this may not represent a practical solution in the context of clinical investigations because it requires time-consuming relaxation measurements. Another limitation of our study was that we used the same LCModel basis-set for analysis of short and long echo-time spectra, while Skoch et al (12) used a customized basis set for long echo-time spectra that included a simulated peak at 2.1 ppm. As most studies using IMCL for the assessment of insulin resistance focus on the lipid peak at 1.3 ppm, our goal was to assess whether long echo-time spectra would provide different data from this particular resonance compared to short echo-time spectra. In our study, long echo-time spectra did not offer any advantage over short echo-time spectra with regard to peak separation and linewidth. Furthermore, short echo-time spectra had higher SNR and better reproducibility than long echo-time spectra.

In conclusion, IMCL quantification using short and long echo-time 1H-MRS at 3.0 T is useful to detect differences in muscle lipid content in obese and normal-weight subjects. In addition, IMCL correlated with body composition and markers of insulin resistance in this population with no significant difference in correlations between short and long echo-times. Short echo-time 1H-MRS had better SNR and better reproducibility compared to long echo-time.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant numbers: RO1 HL-077674, UL1 RR025758, K23 RR-23090.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacob S, Machann J, Rett K, et al. Association of increased intramyocellular lipid content with insulin resistance in lean nondiabetic offspring of type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1999;48:1113–1119. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krssak M, Falk Petersen K, Dresner A, et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia. 1999;42:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s001250051123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Ghomi RH, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Miller KK. Peak growth hormone-releasing hormone-arginine-stimulated growth hormone is inversely associated with intramyocellular and intrahepatic lipid content in premenopausal women with obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3995–4002. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodpaster BH, Theriault R, Watkins SC, Kelley DE. Intramuscular lipid content is increased in obesity and decreased by weight loss. Metabolism. 2000;49:467–472. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha R, Dufour S, Petersen KF, et al. Assessment of skeletal muscle triglyceride content by (1)H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in lean and obese adolescents: relationships to insulin sensitivity, total body fat, and central adiposity. Diabetes. 2002;51:1022–1027. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thamer C, Machann J, Bachmann O, et al. Intramyocellular lipids: anthropometric determinants and relationships with maximal aerobic capacity and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1785–1791. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra A, Sinha S, Kumar M, Jagannathan NR, Pandey RM. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of soleus muscle in non-obese healthy and Type 2 diabetic Asian Northern Indian males: high intramyocellular lipid content correlates with excess body fat and abdominal obesity. Diabet Med. 2003;20:361–367. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Barlow RB, Librizzi J, Dolan S, Grinspoon S. Increased intramyocellular lipid accumulation in HIV-infected women with fat redistribution. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:609–614. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00797.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Bredella MA, Ouellette H. Intramyocellular lipid quantification: comparison between 3.0- and 1.5-T (1)H-MRS. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Halpern EF, Jensen ME, Rosenthal DI, Palmer WE. Intramyocellular lipid quantification: repeatability with 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2005;236:609–614. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362041661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagannathan NR, Wadhwa S. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) study of post polio residual paralysis (PPRP) patients. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skoch A, Jiru F, Dezortova M, et al. Intramyocellular lipid quantification from 1H long echo time spectra at 1.5 and 3 T by means of the LCModel technique. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;23:728–735. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison DB, Paultre F, Maggio C, Mezzitis N, Pi-Sunyer FX. The use of areas under curves in diabetes research. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:245–250. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weis J, Johansson L, Ortiz-Nieto F, Ahlstrom H. Assessment of lipids in skeletal muscle by LCModel and AMARES. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:1124–1129. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drost DJ, Riddle WR, Clarke GD. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the brain: report of AAPM MR Task Group #9. Med Phys. 2002;29:2177–2197. doi: 10.1118/1.1501822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krssak M, Mlynarik V, Meyerspeer M, Moser E, Roden M. 1H NMR relaxation times of skeletal muscle metabolites at 3 T. Magma. 2004;16:155–159. doi: 10.1007/s10334-003-0029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naressi A, Couturier C, Devos JM, et al. Java-based graphical user interface for the MRUI quantitation package. Magma. 2001;12:141–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02668096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borkan GA, Gerzof SG, Robbins AH, Hults DE, Silbert CK, Silbert JE. Assessment of abdominal fat content by computed tomography. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:172–177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa Y, Hattori M, Harada K, Shirase R, Bando M, Okano G. Age-related changes in intramyocellular lipid in humans by in vivo H-MR spectroscopy. Gerontology. 2007;53:218–223. doi: 10.1159/000100869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perseghin G, Scifo P, De Cobelli F, et al. Intramyocellular triglyceride content is a determinant of in vivo insulin resistance in humans: a 1H-13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment in offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. Diabetes. 1999;48:1600–1606. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:171–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schick F, Eismann B, Jung WI, Bongers H, Bunse M, Lutz O. Comparison of localized proton NMR signals of skeletal muscle and fat tissue in vivo: two lipid compartments in muscle tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:158–167. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]