Abstract

Background:

Lung transplantation is associated with a high incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The presence of GERD is considered a risk factor for the subsequent development of obliterative bronchiolitis (OB), and surgical correction of GERD by gastric fundoplication (GF) may be associated with increased freedom from OB. The mechanisms underlying a protective effect from OB remain elusive. The objective of this study was to analyze the flow cytometric properties of BAL cells in patients who have undergone GF early after transplant.

Methods:

In a single-center lung transplant center, eight patients with GERD who were in the first transplant year underwent GF. Prior to and immediately following GF, BAL cells were analyzed by polychromatic flow cytometry. Spirometry was performed before and after GF.

Results:

GF was associated with a significant reduction in the frequency of BAL CD8 lymphocytes expressing the intracellular effector marker granzyme B, compared with the pre-GF levels. Twenty-six percent of CD8 cells were granzyme Bhi pre-GF compared with 12% of CD8 cells post-GF (range 8%-50% pre-GF, 2%-24% post-GF, P = .01). In contrast, GF was associated with a significant interval increase in the frequency of CD8 cells with an exhausted phenotype (granzyme Blo, CD127lo, PD1hi) from 12% of CD8 cells pre-GF to 24% post-GF (range 1.7%-24% pre-GF and 11%-47% post-GF, P = .05). No significant changes in spirometry were observed during the study interval.

Conclusions:

Surgical correction of GF is associated with a decreased frequency of potentially injurious effector CD8 cells in the BAL of lung transplant recipients.

Lung transplantation represents a life-saving procedure in individuals with end-stage lung disease. Despite advances in surgical technique and improvements in early outcomes, < 50% of patients survive > 5 years posttransplant. The major limitation to long-term survival is a high rate of obliterative bronchiolitis (OB).1 Many factors are proposed as triggers to OB. In a rat model of lung transplantation, instillation of gastric fluid into the lungs resulted in histopathology similar to OB.2 Observational studies in humans show that patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) experience an increased risk of death and decreased freedom from rejection.3 Finally, small case series in patients with fibrotic lung disease have suggested that surgical correction of GERD leads to stabilization of disease.4,5 These findings implicate GERD as a trigger of airway fibrosis. The mechanisms underlying the initiation of this fibrosis remain elusive. Presumably, contents found in gastric fluid, such as bile salts and trypsin, when exposed to epithelium, recruit into the lung injurious cells such as cytotoxic CD8s, but this has yet to be shown in humans. Prior studies have demonstrated a correlation between airway bile salts and a diagnosis of OB, but what events precede OB are unknown.6

Because fibrosis of the terminal airways is a process that evolves over years, we hypothesized that prior to the establishment of this injury pattern, patients with GERD would demonstrate recruitment of activated T cells into the lungs. The rationale for undertaking this investigation was that if we could detect a signal associated with immunologic activation early after transplant, it would validate attempts to control GERD with surgical correction. In our lung transplant cohort, we identified patients who had significant GERD postoperatively and who underwent surgical correction of GERD. In this manner, we were able to assess the lung T-cell milieu in individual patients before and after an intervention. We assessed the T-cell BAL characteristics before and after surgical gastric fundoplication (GF). Using this uniquely controlled clinical approach, we found that GF is associated with a decrease in CD8+ effector T cells. These data indicate a mechanistic relationship between the control of GERD and the prevention of OB.

Materials and Methods

Patients

All studies were performed in accordance with the Emory institutional review board. Patients who underwent a lung transplant at Emory University between January 2007 and July 2008 were screened for GERD using a pH probe as our standard clinical protocol. Patients with a DeMeester score ≥ 14, corresponding to the 95th percentile for proximal esophageal acidity, were considered to have GERD. Forty-four patients were eligible to have GERD screening, and 38 patients completed screening. Twenty-one of 38 patients had a positive GERD study, of which eight elected to undergo GF and 13 were managed without surgery, based on patient preference. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Before and after GF, patients underwent surveillance bronchoscopy. BAL was obtained a mean of 20 days before GF (range 1-70 days) and a mean of 33 days after GF (range 14-73 days). During bronchoscopy, BAL and transbronchial lung biopsy were performed. The BAL of patients who had had a positive reflux study but did not undergo GF was assessed at 3, 6, and 9 months posttransplant during their protocol bronchoscopies.

Table 1.

—Patient Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Patient | Disease | Time to GF, d | Pre-GF Pathology | Post-GF Pathology |

| 64 M | IPF | 51 | A2B0 | A0B0 |

| 48 M | IPF | 35 | A2B0 | A0B0 |

| 60 M | COPD | 140 | A0B0 | A0B0 |

| 59 M | COPD | 30 | A0B0 | A0B0 |

| 51 F | Sarcoidosis | 160 | A0B0 | A1B0 |

| 50 F | COPD | 116 | A0B0 | A0B0 |

| 61 M | IPF | 154 | A0B0 | A0B0 |

| 62 M | IPF | 155 | A0B0 | A0B0 |

F = female; GF = gastric fundoplication; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; M = male.

BAL fluid was obtained in a standardized fashion by wedging the bronchoscope into the right middle lobe or lingula and instilling a total of 180 mL saline in 30-mL aliquots, followed by suctioning. The transbronchial lung specimens were evaluated for acute cellular rejection (ACR) with International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant criteria7 by a pulmonary pathologist who was unaware of the patient’s treatment stage. Baseline immunosuppression did not change between samples and none of the patients received pulse high-dose corticosteroids between the before and after studies. BAL specimens were subjected to flow cytometry.

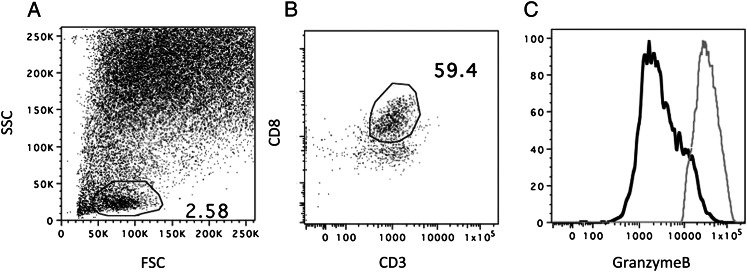

Flow Cytometry

The cellular fraction of the BAL was obtained by centrifugation followed by red cell lysis. Mononuclear cells were then stained with various combinations of antibodies to define subpopulations. All preparations were prepared and labeled fresh on the day of bronchoscopy. Several populations of CD4 and CD8 cells were measured: naive cells, central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), exhausted T cells, granzyme Bhi T cells, and armed effector T cells, according to the definitions in Table 2. Flow cytometry, using the same parameters on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), was performed to allow for simultaneous study of lung and peripheral T-cell phenotypes. For each panel, 1 million cells were antibody labeled. All experiments were performed on an LSRII flow cytometer (Beckton Dickenson; Franklin Lakes, NJ). Prior to each sample, midrange Sphero calibration beads (Beckton Dickenson) were used to ensure that fluoresce peaks between samples were equal. Light scatter gates were used to detect a lymphocyte population (generally 1%-5% of the total BAL cellular fraction). CD8 cells were defined by being positive for both CD3 and CD8 and negative for CD4. PBMC CD8 cells demonstrate a bimodal population of granzyme Bhi and lo cells; hence, this population was used to set the granzyme Bhi gate when applied to BAL specimens (Fig 1). All specimens were analyzed with FlowJo Software (Treestar; Ashland, OR).

Table 2.

—Definitions of T-Cell Subsets Based on Flow Cytometric Properties

| Naive T Cells | Central Memory T Cells | Effector Memory T Cells | Exhausted T Cells | Armed Effector |

| CD45ROlo | CD45ROhi | CD45ROhi | CD127lo | Granzyme Bhi |

| CCR7hi | CCR7hi | CCR7lo | PD1hi | |

| Granzyme Blo |

Figure 1.

Sample gating strategy for lymphocytes from BAL: light scatter gates were used to identify a population of lymphocytes (A). CD8 lymphocytes were CD8+CD3+ (B) and also CD4 negative (not shown). Granzyme B were gated on BAL cells (solid line) using the granzyme Bhi population of CD8 cells simultaneously from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (dotted line) (C). FSC = forward scatter; SSC = side scatter.

Validation of Granzyme B as a Biomarker for ACR

Correlation of CD8 granzyme B frequency and ACR was performed by two analyses. First, the frequency of BAL CD8 cells that were positive for granzyme B in lung transplant recipients experiencing their first episode of ≥ A2 ACR was compared with the frequency in the same patients on subsequent bronchoscopy after treatment with high-dose corticosteroids. Thirteen patients who were not subjected to GF and who had an episode of ≥ A2 ACR followed by a bronchoscopy showing no ACR were analyzed. Next, cumulative rejection scores were calculated for a total of 43 non-GF patients who underwent a lung transplant during the time of our study and in whom we had 1 year of total rejection score data and ≥ 5 BAL samples. The total A score and B score, including A1 and B1 rejection events, was summed for each patient and assessed as a continuous variable vs the mean granzyme Bhi frequency of CD8 cells over the entire 1-year period.

Pulmonary Function Testing

All study lung transplant patients underwent standard serial pulmonary function testing by American Thoracic Society criteria, starting 1 month after transplant. Testing was performed biweekly for the first 3 months and then monthly. The FEV1, and FVC were measured. After GF, patients were allowed to recover before the next set of pulmonary function testing values was obtained.

Results

Surgical Correction of GERD Is Associated With a Decreased Frequency of Effector CD8 Cells

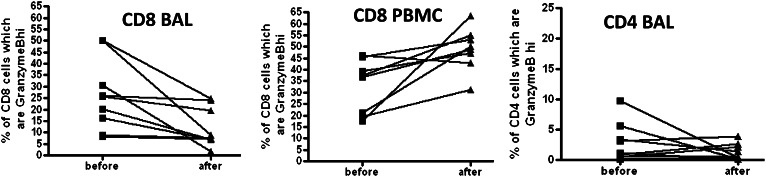

Granzyme B is a cytotoxic intracellular protein critical for cell-mediated lysis, is associated with T-cell effector functions, and is significantly more prevalent on CD8 than on CD4 T lymphocytes. In the eight patients who underwent GF, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of BAL CD8 cells that expressed high levels of granzyme B. As shown in Figure 2, there was an overall decrease in BAL granzyme B expression on CD8 cells (of 26% pre-GF, 12% post-GF, range 8%-50% pre-GF, 2%-24% post-GF, P = .014). When the absolute number of granzyme Bhi CD8-positive cells was estimated, we did not find any significant difference in the before- and after-GF conditions, but the degree of variability in this measure was marked with a range of 0.3 to 1,880 granzyme Bhi cells/mL fluid (not shown). In the aftermath of GF, there was an increase in the PBMC CD8 pool expressing high levels of this cytotoxic granule (33% pre-GF, 49% post-GF, range 18%-46% pre-GF, 31%-63% post-GF, P = .007).

Figure 2.

CD8 T cells demonstrate decreased granzyme B expression in the BAL, but increased granzyme B expression in the PBMC compartment in the aftermath of gastric fundoplication (GF). CD4 BAL cells did not significantly change in the aftermath of GF, but granzyme B expression was significantly lower in CD4 cells compared with CD8 cells. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of the abbreviation.

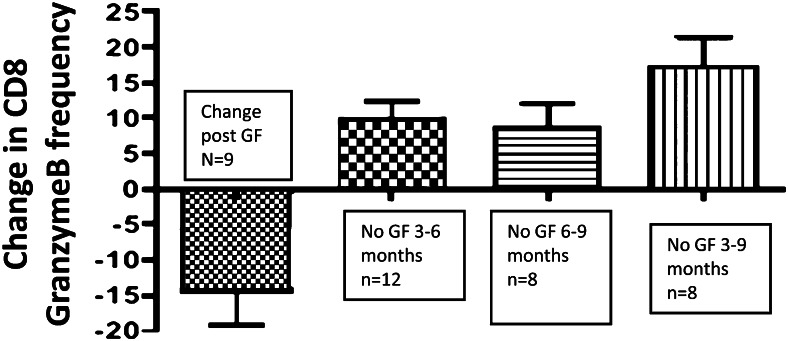

Thirteen patients who had confirmed GERD by pH probe after transplant elected not to undergo GF. We captured relevant data in 12 of the 13 patients for the 3-to-6 month period and in eight of the 13 patients for the 6-to-9 month period. We calculated the CD8 granzyme B frequency in this group at 3, 6, and 9 months posttransplant, roughly covering the period of observation in the GF patients. BAL granzyme B frequency increased slightly in the non-GF group for each period of observation and the change over time between the GF and non-GF group was highly significant by unpaired t test P < .001 (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in BAL CD8 granzyme B frequency over time: first column shows change in before- and after-GF frequency. The next three columns show the change in BAL CD8 granzyme B in patients who did not get surgical treatment, at various time intervals posttransplant. P < .001 between GF patients and all time intervals for non-GF patients by nonparametric t test. See Figure 2 legend for expansion of the abbreviation.

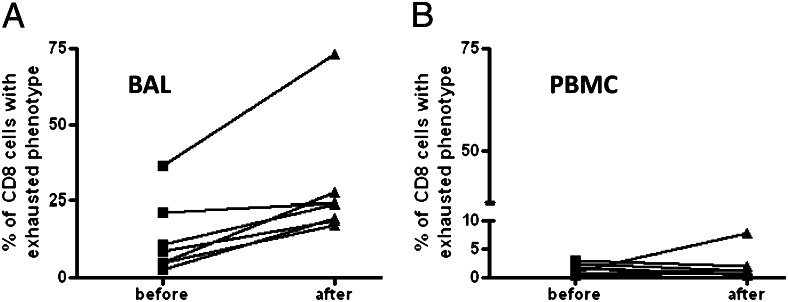

Surgical Correction of GERD Is Associated With an Increased Frequency of Exhausted T cells

In HIV and hepatitis C, these exhausted T cells, which express PD-1 and downregulate CD127, are associated with poor viral control.8‐10 Theoretically, exhausted T cells in the setting of lung transplantation could represent a good prognostic indicator. We observed an increase in exhausted T cells in the BAL from 12% to 24% in the before- and after-GF situations (range 1.7%-24% pre-GF and 11%-47% post-GF, P = .05), but it is important to note that this result is, in part, driven by a single outlier, and the overall magnitude of the difference is modest (Fig 4A). Notably, there were few exhausted CD8s detected in the PBMC (Fig 4B) either before or after GF.

Figure 4.

In the aftermath of GF there were increased exhausted CD8 cells (A), defined as CD127loPD1hi granzyme Blo (P = .05), but no significant change was detected in the PBMC compartment (B). See Figure 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

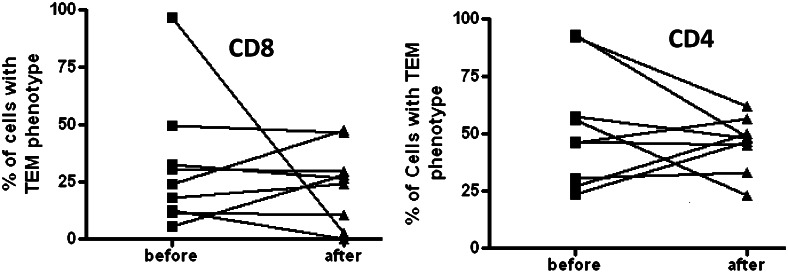

GF Did Not Alter Naive, Central Memory, or Effector Memory Populations of CD8 Cells or CD4 Lymphocytes

Memory cells have been subdivided into distinct lineages: TEM and TCM.11 Although the exact linage relationship between TEM and TCM remains unclear, the functional role of these two lineages is less controversial. TCM preferentially populate secondary lymphoid organs and interact with antigen-presenting cells, whereas TEM act as a first line of defense, inhabiting sites of pathogen entry such as the lung, gut, and skin. We quantified TEM and TCM CD8 populations in the BAL before and after GF. Importantly, and not surprisingly, we found that both before and after GF, the majority of CD8 cells in the lung were phenotypically TEM. Nevertheless, there were no differences in relative TEM frequencies before and after GF (Fig 5), suggesting that GF is not associated with a general decrease in TEM cells but rather, a decrease in cells with effector function.

Figure 5.

No significant differences in CD8 or CD4 TEM cells were observed in the BAL before and after GF. TEM = effector memory T cells. See Figure 2 legend for expansion of the other abbreviation.

In humans, ACR early posttransplant is associated with elevated numbers of BAL CD8 cells.12 Nevertheless, we sought to determine if correction of GERD was associated with differences in BAL CD4 cells. Although a small fraction of CD4 cells do express the cytotoxic granule granzyme B, we did not detect any differences in granzyme B expression in the before and after bronchoscopies in the CD4s (not shown), nor were there discernable differences in BAL CD4 TCM and TEM proportions (Fig 5).

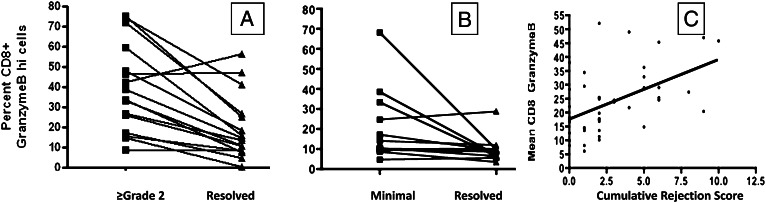

CD8 Granzyme B Correlates With Acute Rejection Score

Clinical studies in solid organ transplantation, including lung transplantation, have shown that granzyme B increases in ACR.13‐17 To bolster our assertion that BAL granzyme B was a clinically meaningful biomarker, we then measured BAL CD8 granzyme B expression in patients with ACR. ACR has been shown by multiple analyses to prospectively correspond to the subsequent development of OB.18,19 Furthermore, there are emerging data that link the frequency of certain cell types in the BAL fluid to risk of ACR.20‐22 We assessed CD8 granzyme B frequency in patients with the first episode of ACR and compared it with the subsequent resolved biopsy after pulse corticosteroids. As shown in Figure 6A, there was a significant decrease in BAL CD8 granzyme B frequency after treating ≥ grade 2 ACR. A similar phenomenon was seen when we considered the first episode of minimal rejection (Fig 6B). To see if patients with more episodes of abnormal lung histology had higher levels of BAL granzyme B, we calculated the total 1-year rejection score in a similar fashion to Glanville et al23 over a 1-year period. This rejection score was compared as a continuous variable with the mean CD8 granzyme Bhi frequency for each patient. We found a statistically significant association between cumulative rejection score and mean BAL CD8 granzyme B frequency. These findings support measurement of granzyme B expression as a clinically meaningful biomarker and validate the study of this marker on CD8 cells with respect to other clinical situations such as GERD.

Figure 6.

Acute rejection associated with increased BAL CD8 granzyme B. Individual patient’s first episode of ≥ grade 2 rejection was compared with the aftermath of treated acute cellular rejection (ACR) and demonstrated a significant reduction in CD8 granzyme B in the setting of treated ACR (mean 36% pre vs 14% post, P = .002) (A). Individual patients with minimal (grade 1) rejection were analyzed as in A (mean 22% vs 10%, P = .032) (B). Mean BAL CD8 granzyme B during 1 year of follow-up correlates with cumulative 1-year rejection score (P < .001, r2 = 0.25) by univariate regression (C).

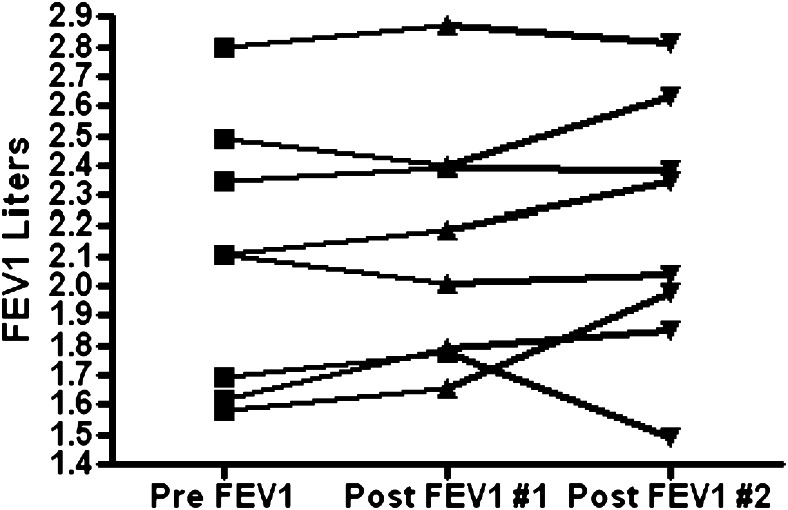

GF Within the First Transplant Year Is Not Associated With Measurable Changes in Lung Physiology

The patients studied in this report performed monthly pulmonary function testing. We were interested to see if GF was associated with a significant change in lung spirometry. We measured FEV1 and FVC in patients before and after GF. All patients were given at least 3 weeks to recover from surgery before the after-surgery spirometric values were calculated. We observed a wide range in values of FEV1 among this cohort but did not detect a meaningful change in FEV1 (Fig 7), present predicted FEV1, or forced expiratory flow 25-75 (not shown) when comparing the before- and after-surgery measurement.

Figure 7.

Spirometric values in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) before GF and on two subsequent study points post-GF (P = not significant between the pre-GF value and both post-GF values). See Figure 2 legend for expansion of the abbreviation.

Discussion

Research involving human lung transplant recipients suggests that GERD is a risk factor for OB. Hence, surgical correction of GERD has garnered considerable interest. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms for the protective effect of GF remain elusive. Emerging in vitro data suggest that constituents of reflux cause airway injury. These mechanisms include a degradation of surfactant by bile salts,24 a dampening of the macrophage phagocytic function by bile salts,25,26 a permissive effect of gastric juice on Pseudomonas colonization,27 and a stimulatory effect of trypsin on the respiratory epithelium to release interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and RANTES.28,29

The initial reports linking GERD to OB showed that patients with GERD had an increased OB, but, importantly, several years of follow-up were required to detect a difference between GERD and non-GERD patients,3,6,30 implying that injury occurring through reflux occurs over time, after continuous low-grade attack. In contrast, in a rat transplant model, airway fibrosis occurred nearly contemporaneously with an influx of lung T cells when the experimental animals were subjected to tracheal instillation of massive amounts of gastric fluid.31 We speculated that in humans, GERD does contribute to OB because of a slow repetitive injury process involving intrapulmonary recruitment of injurious T cells as one component of a complicated inflammatory process. Here we have shown that correction of GERD is associated with alteration of the T lymphocytes with the lung. Patients were assessed early after transplant before any decline in spirometry. We assessed lung lavage cells before and after surgery and without any additional modifications to their underlying immunosuppression. We found that surgical correction was associated with a decreased signal of T-cell activation in the lung, but not in the blood.

There are important limitations to note. Although we performed paired analysis in which each patient served as his/her own before and after control, we were not able to control for other immunologic events that differed in the before- and after-GF setting. Two of eight patients had ACR before GF but did not have ACR after surgery. In contrast, one of eight patients had no ACR prior to GF but did have minimal ACR after GF. When these episodes are censored from the analysis, the data lose statistical significance. Although it remains possible that our data are due, in part, to resolution of ACR, an unanswered question in lung transplantation is whether the phenomenon of ACR can be disaggregated from injury caused by GERD or if histologic ACR is, at the microscopic level, one manifestation of reflux. It is notable that none of the patients in the before-GF setting received any augmented immunosuppression, because they were felt to be clinically stable. The unintentional benefit of this lack of a change in immunosuppression is that the decrease in granzyme Bhi CD8 cells in the aftermath of GF cannot be ascribed to the use of augmented immunosuppression such as a corticosteroid pulse. It is theoretically possible that the reduction in granzyme B expression we saw in the before and after analysis was related to resolving injury after the transplant itself. Arguing against that possibility is the fact that the before and after specimens were obtained in close proximity to each other (mean 1.8 months between samples).

Many of the patients in our center who were found to have reflux did not undergo reflux surgery. Our analysis here is retrospective and we did not have a systematic protocol in place to determine which patients should undergo GF. Hence, our data could be biased toward performing GF on sicker patients. Nevertheless, patients who did not undergo GF had higher frequencies of granzyme B CD8s, which suggests that GF likely does modulate the pulmonary immunologic milieu in the short term.

Conclusions

There is a growing appreciation that GERD is associated with a risk of development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). The transplant community is also searching for a breakthrough therapy because outcomes remain suboptimal. Hence, there is enthusiasm for the potential therapeutic benefit of GF. Nevertheless, it is too early to make surgical correction for GERD the standard of care. There has never been a comparison study of surgical correction to medical management in reflux. GF may predispose individuals to operative risk and subsequent morbidity. Furthermore, there is uncertainty regarding the mechanism by which GERD predisposes to BOS. Our data suggest that in humans, GERD induces an influx of T cells, which are capable of causing injury. We acknowledge that these results are largely hypothesis generating; no corrections for multiple comparisons were made and the sample size was relatively small. Going forward, future trials with randomization of patients are needed before we can definitively endorse GF. The readouts for these studies should include both immediate flow cytometric data and longitudinal data, such as the subsequent development of BOS.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Neujahr: contributed to study design, data analysis, data collection, and manuscript preparation.

Dr Mohammed: contributed to data analysis.

Ms Ulukpo: contributed to data collection.

Dr Force: contributed to data collection and manuscript preparation.

Dr Ramirez: contributed to data collection.

Dr Pelaez: contributed to data collection.

Dr Lawrence: contributed to data collection.

Dr Larsen: contributed to study design.

Dr Kirk: contributed to study design and manuscript preparation.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Abbreviations

- ACR

acute cellular rejection

- BOS

bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GF

gastric fundoplication

- OB

obliterative bronchiolitis

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TCM

central memory T cells

- TEM

effector memory T cells

Funding/Support: This work was supported by Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation [Grant #631634718] to David C. Neujahr, principal investigator.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Burke CM, Theodore J, Dawkins KD, et al. Post-transplant obliterative bronchiolitis and other late lung sequelae in human heart-lung transplantation. Chest. 1984;86(6):824–829. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li B, Hartwig MG, Appel JZ, et al. Chronic aspiration of gastric fluid induces the development of obliterative bronchiolitis in rat lung transplants. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(8):1614–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis RD, Jr, Lau CL, Eubanks S, et al. Improved lung allograft function after fundoplication in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease undergoing lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125(3):533–542. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raghu G, Yang ST, Spada C, Hayes J, Pellegrini CA. Sole treatment of acid gastroesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case series. Chest. 2006;129(3):794–800. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linden PA, Gilbert RJ, Yeap BY, et al. Laparoscopic fundoplication in patients with end-stage lung disease awaiting transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131(2):438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Ovidio F, Mura M, Tsang M, et al. Bile acid aspiration and the development of bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(5):1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousem SA, Berry GJ, Cagle PT, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the classification of pulmonary allograft rejection: Lung Rejection Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15(1 Pt 1):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443(7109):350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang JY, Zhang Z, Wang X, et al. PD-1 up-regulation is correlated with HIV-specific memory CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in typical progressors but not in long-term nonprogressors. Blood. 2007;109(11):4671–4678. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radziewicz H, Ibegbu CC, Fernandez ML, et al. Liver-infiltrating lymphocytes in chronic human hepatitis C virus infection display an exhausted phenotype with high levels of PD-1 and low levels of CD127 expression. J Virol. 2007;81(6):2545–2553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02021-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregson AL, Hoji A, Saggar R, et al. Bronchoalveolar immunologic profile of acute human lung transplant allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2008;85(7):1056–1059. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318169bd85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Hartono C, Ding R, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of renal-allograft rejection by measurement of messenger RNA for perforin and granzyme B in urine. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(13):947–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascoe MD, Marshall SE, Welsh KI, Fulton LM, Hughes DA. Increased accuracy of renal allograft rejection diagnosis using combined perforin, granzyme B, and Fas ligand fine-needle aspiration immunocytology. Transplantation. 2000;69(12):2547–2553. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeevi A, Pavlakis M, Spichty K, et al. Prediction of rejection in lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1-2):291–292. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cashion A, Sabek O, Driscoll C, Gaber L, Kotb M, Gaber O. Correlation of genetic markers of rejection with biopsy findings following human pancreas transplant. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(1):106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi R, Yang J, Jaramillo A, et al. Correlation between interleukin-15 and granzyme B expression and acute lung allograft rejection. Transpl Immunol. 2004;12(2):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bando K, Paradis IL, Similo S, et al. Obliterative bronchiolitis after lung and heart-lung transplantation. An analysis of risk factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(05)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husain AN, Siddiqui MT, Holmes EW, et al. Analysis of risk factors for the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):829–833. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9607099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clelland C, Higenbottam T, Stewart S, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy during acute rejection and infection in heart-lung transplant patients. Studies of cell counts, lymphocyte phenotypes, and expression of HLA-DR and interleukin-2 receptor. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(6 Pt 1):1386–1392. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crim C, Keller CA, Dunphy CH, Maluf HM, Ohar JA. Flow cytometric analysis of lung lymphocytes in lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(3):1041–1046. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynaud-Gaubert M, Thomas P, Gregoire R, et al. Clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cell phenotype analyses in the postoperative monitoring of lung transplant recipients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glanville AR, Aboyoun CL, Havryk A, Plit M, Rainer S, Malouf MA. Severity of lymphocytic bronchiolitis predicts long-term outcome after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(9):1033–1040. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Ovidio F, Mura M, Ridsdale R, et al. The effect of reflux and bile acid aspiration on the lung allograft and its surfactant and innate immunity molecules SP-A and SP-D. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(8):1930–1938. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greve JW, Gouma DJ, Buurman WA. Bile acids inhibit endotoxin-induced release of tumor necrosis factor by monocytes: an in vitro study. Hepatology. 1989;10(4):454–458. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calmus Y, Guechot J, Podevin P, Bonnefis MT, Giboudeau J, Poupon R. Differential effects of chenodeoxycholic and ursodeoxycholic acids on interleukin 1, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by monocytes. Hepatology. 1992;16(3):719–723. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vos R, Blondeau K, Vanaudenaerde BM, et al. Airway colonization and gastric aspiration after lung transplantation: do birds of a feather flock together? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(8):843–849. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cromwell O, Hamid Q, Corrigan CJ, et al. Expression and generation of interleukin-8, IL-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by bronchial epithelial cells and enhancement by IL-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Immunology. 1992;77(3):330–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stellato C, Beck LA, Gorgone GA, et al. Expression of the chemokine RANTES by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Modulation by cytokines and glucocorticoids. J Immunol. 1995;155(1):410–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantue E, III, Appel JZ, III, Hartwig MG, et al. J. Maxwell Chamberlain Memorial Paper. Early fundoplication prevents chronic allograft dysfunction in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(4):1142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appel JZ, III, Lee SM, Hartwig MG, et al. Characterization of the innate immune response to chronic aspiration in a novel rodent model. Respir Res. 2007;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]