Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms have been linked to traumatic experiences, including intimate partner violence. However, not all battered women develop PTSD symptoms. The current study tests attachment style as a moderator in the abuse–trauma link among a community sample women in violent and non-violent relationships. Both attachment anxiety and dependency were found to moderate the relation between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms. However, attachment closeness did not function as a moderator. Differences in attachment may help to explain why certain victims of domestic abuse may be more susceptible to experiencing PTSD symptoms. Clinically, these findings may aid in the prediction and prevention of PTSD symptoms in women victimized by intimate partner abuse.

Keywords: Adult attachment, Domestic violence, Traumatic symptoms, PTSD, Partner violence

Introduction

Attachment theory originally referred to the relationship between children and their caretakers, and how these relationships affect a child’s self-concept and view of the social world (Bowlby 1979; Collins and Read 1990). According to the theory, children develop internal models, beliefs, and expectations about “whether or not the caretaker is someone who is caring and responsive,” and whether or not “the self is worthy of care and attention” (Collins and Read 1990). Children may be secure, anxious and ambivalent, or avoidant in response to separations and reunions with their caregivers (Bowlby 1979). These internal models of the self and others are thought to generalize to other relationships and shape affect regulation throughout the lifespan (Ainsworth et al. 1978; Alexander and Warner 2003; Bowlby 1979; Main et al. 1985).

Applying the theory to adults, Hazan and Shaver (1987) developed a self-report measure of attachment styles in adult romantic relationships. Viewed as categories, a secure group described their relationships as mostly positive and trusting, thus indicating that they felt worthy of love and believed that could have caring relationships (Hazan and Shaver 1987). Avoidant individuals were characterized by fear of intimacy and anxious–ambivalent lovers were obsessed with the desire for reciprocation and union (Hazan and Shaver 1987). These two insecure groups reported more negative experiences and emotions associated with their romantic relationships than the secure group. Secure individuals were found to have longer, more stable relationships, while anxious–ambivalent lovers were found to have a more anxious and obsessive views of love, and avoidant individuals tended to be the least accepting of their partner (Hazan and Shaver 1987).

Collins and Read (1990) modified the Hazan and Shaver questionnaire to empirically test the dimensions underlying the three attachment patterns: closeness, dependency, and anxiety. Closeness relates to a secure attachment style and reflects the ease, desire, and comfort one has in becoming close to her partner. The dependent attachment measure involves one’s expectations that her partner will be reliable and trustworthy. Finally, attachment anxiety refers to one’s fears of abandonment and rejection. The dimensional model allows for variation of individuals across the three factors that underlie adult attachment styles.

Attachment, Abuse, and Trauma

Attachment, family violence, and stress reactions are all interrelated. First, studies have found that insecure attachment patterns are associated with intimate partner violence (Babcock et al. 2000; Dutton and Painter 1993) and difficulty in battered women leaving an abusive relationship (Shurman and Rodriguez 2006), as attachment anxiety exacerbates the normal fear of separation and loss in ending long-terms relationships (Bartholomew and Allison 2006). Secondly, physical and psychological intimate partner abuse has repeatedly been shown to be associated with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; Babcock et al. 2008; Jones et al. 2001), however, most women who experience IPV do not develop PTSD symptoms (Jones et al. 2001). Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of women will be physically, sexually, or psychologically abused at some point in their lives (Walker 2000) and 28% of adult women have been physically abused by their partners (Straus et al. 1980). Among community samples of abused women, approximately 30% meet criteria for PTSD (Cascardi et al. 1999), although the rates of PTSD may be much higher among shelter samples (Arias and Pape 1999; Kemp et al. 1991). Finally, attachment patterns predict how adults tend to react to stress (Besser and Priel 2005), including traumatic events. Specifically, attachment insecurity, anxiety and avoidance are related to depression, anxiety, (Besser and Priel 2005) and PTSD (Solomon et al. 2008).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms include intrusive thoughts of the event, intense physiological distress when exposed to cues that resemble the event, difficulty falling asleep, feelings of detachment, exaggerated startle response, and hypervigilance (APA 1994). Studies have found a relations between insecure attachment styles and PTSD in a variety of populations, including military recruits, prisoners of war, war veterans, Holocaust survivors (Declercq and Palmans 2006) and victims of family violence (Stovall-McClough et al. 2008). Several studies have examined attachment as a mediator or moderator between child abuse and the development of psychological symptoms (Roche et al. 1999; Twaite and Rodriguez-Srednicki 2004; Whiffen et al. 1999) and one study found positive correlations attachment avoidance and anxiety with both adult victimization and PTSD symptoms (Elwood and Williams 2007). Both PTSD and insecure attachment patterns are related to negative cognitions about the self, the world, and the dependability of others (Elwood and Williams 2007); and both attachment anxiety and dependency can lead to problems in emotional regulation that are implicated in the development of PTSD (Solomon et al. 2008; Zakin et al. 2003).

Because attachment insecurity, intimate partner violence victimization, and PTSD are interrelated, the current study poses that attachment patterns function as a moderator of the relation between abuse and trauma. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), a moderator is a variable that “affects the direction and/or strength of the relation between an independent or predictor variable and a dependent or criterion variable.” The fact that IPV does not always lead to PTSD symptoms suggests that other variables should be considered for moderator effects. One previous study found no evidence that attachment moderated PTSD symptom development after interpersonal trauma (Elwood & Williams 2007). However, that study recruited a sample of college students not necessarily involved in a relationship, used different measures of attachment and traumatic symptoms, and used physical or sexual abuse victim status as a dichotomous outcome variable. The present study examines the possible moderator effects of attachment closeness, anxiety, and dependency (Collins and Read 1990) on the relation between the frequency of IPV experienced in the past year and PTSD symptoms, employing a community sample of couples selected for current relationship problems.

Both attachment anxiety and avoidance are thought to disrupt the coping processes in the aftermath of trauma and thereby increase the risk of developing PTSD and other emotional problems (Solomon et al. 2008). With respect to attachment anxiety, IPV and PTSD symptoms are expected have a stronger relation in conditions of high fear of being unloved or rejected by one’s partner as compared to conditions of low attachment anxiety. Therefore, high attachment anxiety is expected to be a risk factor for developing more severe PTSD symptoms in women who have experienced IPV. Likewise, dependent attachment is also predicted be a risk factor for developing PTSD symptoms. High dependency indicates a strong reliance on one’s partner in conjunction with expectations that the partner is trustworthy, which is incongruous with the partner being abusive. Therefore, the relation between violence and PTSD symptoms are expected to strengthen in conditions of high dependent attachment. Finally, close attachment is predicted to moderate the relationship between violence and PTSD symptoms. Closeness reflects attachment security and the ease and comfort one feels in becoming close to one’s partner. For participants with high scores in close attachment, the relation between IPV and PTSD symptoms is expected to weaken. Therefore, high close/secure attachment is thought to be a protective factor against the development of PTSD.

Method

Participants

Heterosexual couples (N=202) were recruited for the current study as part of a larger project (Costa and Babcock 2008; Costa et al. 2007). Participants responded to local newspaper ads and flyers recruiting “couples experiencing conflict.” Participants must have reported being married or living together for at least 6 months, 18 years of age or older, and able to speak and write English proficiently. Female partners were contacted by phone and administered the violence subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979). To meet preliminary phone screening for the intimate partner violence group (IPV), female partners had to report at least two incidents of male-to-female aggression in the past year. Female-to-male aggression was free to vary. Participants denying a history of physical abuse, but endorsing relationship unhappiness, were also included. Although this group reported no physical violence, all women reported that their male partner perpetrated some psychological abuse in the past year.

Procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger study on psychophysiolgical responding and men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence. (Babcock et al. 2008). The first session included only male participants. The second session included male participants and their female partners. Couples were separated and asked to complete a series of questionnaires. All measures included in this thesis were collected during the second assessment period lasting approximately 3.5 h. Each participant was paid $10 per hour for his or her participation.

Safety Measures

Safety procedures developed by Dr. Anne Ganley were applied here (Babcock et al. 2005; Jacobson et al. 1994). Following the assessment, each participant was debriefed separately to assess danger and safety. Safety plans were developed, if needed. All participants were given referrals for community resources including, but not limited to, counseling services and shelters. Female participants were telephoned one week later to assess whether their participation caused any untoward events. In no cases did women report any subsequent violence due to participation in the laboratory assessments.

Questionnaire Measures

Physical Assault

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al. 1996) was administered to male and female participants separately to assess the type, severity and frequency of intimate partner violence. The CTS2 is a 78-item questionnaire that assesses the frequency of physically, sexually, and psychologically abusive acts that have occurred in the past year. Preliminary internal consistencies of the CTS2 range from .79 to .95 (Straus et al. 1996). For the current study, only women’s reports of men’s physical assault perpetration subscale, comprised of minor (5 items) plus severe (7 items) was used. In this sample, the internal consistencies of the women’s report of men’s physical assault was alpha = .86.

Adult Attachment

The Adult Attachment Scale (AAS) was administered to female participants (Collins and Read 1990). The 18-item scale was used to measure female extents of attachment closeness, dependency, and anxiety. Specifically, this scale measure how comfortable one is with feeling closeness to another person, depending on others for support, and how anxious one feels about the possibilities of a being rejected by their partner. Participants rated how accurately each item in the scale described themselves. Dependency measures included statements such as “I find it difficult to allow myself to depend on others” (Collins and Read 1990). While statements such as “I often worry my partner will not want to stay with me” measured attachment anxiety. Closeness was also measured by statements such as “I find it relatively easy to get close to others.” This scale allowed for attachment to be viewed by a dimensional approach, as opposed to a categorical model, by measuring the underlying dimensions of attachment style.

PTSD Symptoms

The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa and Cashman 1997) was used to assess PTSD symptomatology in the female participants. The PDS is a self-report measure designed to yield a PTSD diagnosis according to the DSM-IV (APA 1994) and a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity for each of three symptom clusters: Reexperiencing α=.84; Avoidance α=88, and Arousal α=.86. Participants must report that they have experienced one or more traumatic events, such as a serious accident, life-threatening illness, sexual assault, non-sexual assault in order to receive a score greater than zero on the subscales or a diagnosis.

Relationship Satisfaction

The 32-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS: Spanier 1976) was administered to men and women in the lab to assess relationship satisfaction, α=.93 for the current study. This scale is reported for descriptive purposes only.

Data Analytic Plan

Moderated Multiple Regression

Three moderated multiple regressions (Aiken and West 1991) were performed using SPSS version 17.0, by entering the conditional (main) effects on step one and interaction between IPV and each of the three attachment scales (depend, close, anxiety) on step two in predicting the severity of PTSD symptoms. Using Excel 2007, the interaction terms were then explained graphically by computing a predicted value of PTSD for those who were one SD above the mean on the predictor (IPV) and moderator (attachment scale) variable (Aiken and West 1991; Frazier et al. 2004).

Results

Demographics

The majority of the sample was African American (48.6%), followed by Caucasians (28.2%) and Hispanics (15%). The participants’ average age for women in non-violent relationships was 31.51 (SD=10.17) and 29.74 (SD=29.74) for women in violent relationships. All of the women were in committed heterosexual relationships. women in non-violent relationships were involved in their relationship for an average of 5.23 (SD=5.48) and women in violent relationships were involved in their relationships for an average of 4.22 years (SD=4.01). Thirty-nine (28.3%) women in violent relationships met criteria for PTSD, as compared to four (9.3%) of women in non-violent relationships, χ2(df=1; N=175) = 4.79, p<.05. There were no significant differences between women in non-violent and violent relationships in regards to age, years in relationship, income, or number of children. Education level differences were significant with non-abused women having a significantly higher amount of education than abused women. See Table 1. Women’s report of male-to-female physical aggression in the past year ranged from 0 to 100 acts, M= 13.70, SD=20.92 across the entire sample.

Table 1.

Demographic differences between non-abused and intimate partner violent (IPV) abused women

| Variable | NA (n=37)

|

IPV (n=138)

|

F(1,173) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| Age | 31.51 | 10.17 | 29.74 | 9.34 | 1.01 |

| Years in relationship | 5.23 | 5.48 | 4.22 | 4.01 | 1.57 |

| Income | 42,398.81 | 25,117.63 | 36,267.99 | 16,063.45 | 3.27 |

| Education levela | 5.06 | 1.71 | 3.97 | 1.84 | 10.60** |

| Number of children | 1.35 | 1.49 | 1.44 | 1.65 | 0.09 |

Education level ranges from 1 = “some high school” to 6 = “college graduate”

p<.01

Preliminary results indicated that of all female participants (N=174), 35 reported no male physical violence in the past year and 139 reported some physical violence with a mean of 17.27 (SD=22.11) violent acts within the past year. Females who reported their partner to have physically abused them in the past year scored a mean of 13.25 (SD= 11.37) on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, with non-physically abused women scoring an average of 8.56 (SD= 9.73). On the AAS, women who had been physically abused by their intimate partner in the past year scored lower on closeness compared to women who reported no IPV in the past year. Abused women scored higher on anxiety, IPV, and PTSD symptoms than non-abused women. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviation and F statistics comparing non-violent and physically abused women and closeness, dependency, and anxiety

| NV (n=35)

|

IPV (n=139)

|

F(1,173) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ | SD | x̄ | SD | ||

| IPV | .000 | (.000) | 17.27 | (22.11) | 21.25*** |

| PTSD | 8.56 | (9.73) | 13.25 | (11.37) | 5.03* |

| CLOSE | 18.91 | (3.06) | 17.72 | (3.76) | 3.01 |

| DEPEND | 18.17 | (3.54) | 16.99 | (3.63) | 2.99 |

| ANXIETY | 13.54 | (4.13) | 17.04 | (4.16) | 19.85*** |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

For all subsequent analyses, abused and non-abused women were combined into one sample to increase the range in the variables of interest. Correlations across the entire sample reveal that all three attachment subscales were found to have significant correlations with IPV. Specifically, close and dependent attachment were discovered to have negative correlations with IPV, and anxiety was positively correlated with IPV. Closeness and anxiety were also found to have significant correlations with PTSD symptoms. Specifically, closeness and PTSD were negatively correlated and anxiety and PTSD were positively correlated. However, there was no relation between dependency and PTSD. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between female report of male physical assault, posttraumatic diagnostic scale, closeness, dependency, and anxiety

| IPV | PTSD | CLOSE | DEPEND | ANXIETY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPV | .30* | −.22* | −.17* | .33* | |

| PTSD | −.39* | −.11 | .46* | ||

| CLOSE | .38* | −.39* | |||

| DEPEND | −.28* | ||||

| ANXIETY |

N=174.

p<.05

Following the methods of Baron and Kenny (1986), three moderated multiple regressions were conducted. The predictor and moderator variables were centered by subtracting their means (Frazier et al. 2004), and three interaction terms were created by multiplying the centered IPV variable by each attachment scale (close, anxiety, and depend) separately. Three separate, hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted by entering IPV and the attachment scale, then the IPV X attachment scale interaction term to predict PTSD symptoms.

Hypothesis 1: Anxiety as a Moderator of the Relation Between Intimate Partner Violence and PTSD Symptoms

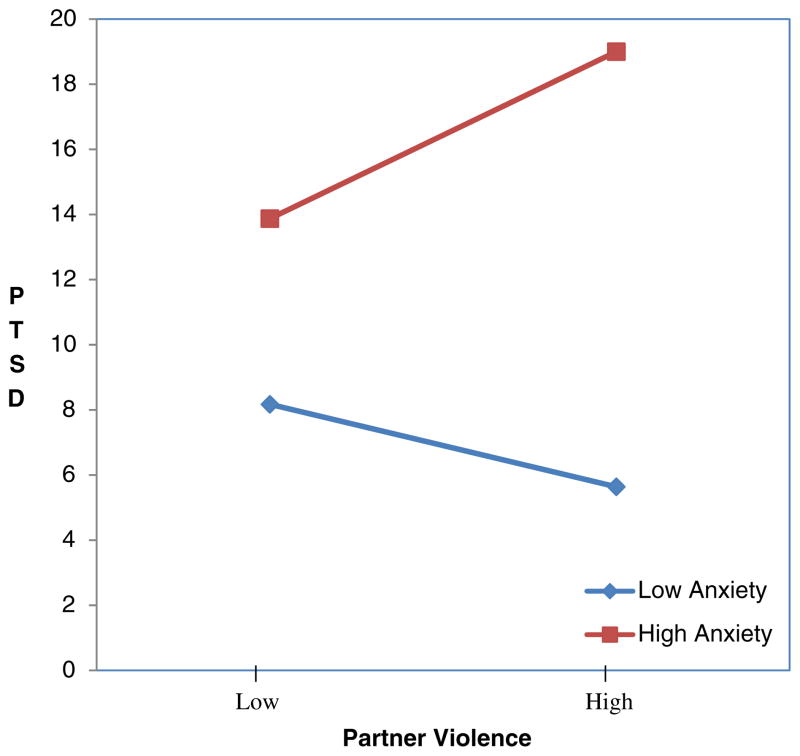

Attachment anxiety was proposed to moderate the relationship between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms. Specifically, conditions of high anxiety were hypothesized to predict more PTSD symptoms than conditions of low anxiety. As preliminary correlations indicated, victims of violence reported higher levels of anxiety, see Table 2. Correlations show that anxiety was correlated to IPV and PTSD symptoms, as expected, see Table 3. The multiple regression found that there was significant interaction between violence and anxiety in predicting PTSD symptoms (β=185, p<.05), see Table 4. Therefore, the hypothesis that anxiety would function as a moderator between violence and PTSD symptoms was supported. Comparing those who scored one SD above and below the mean on attachment reveals that in conditions of high attachment anxiety, intimate partner violence is more strongly related to PTSD symptoms than in conditions of low anxiety. See Fig. 1.

Hypothesis 2: Dependency as a moderator of the relation between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms

Table 4.

Three multiple regressions examining the relation between violence and attachment (N=173)

| Unstandardized B | SE B | Standardized Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||

| IPV | .03 | .05 | .06 |

| Anxiety | 1.09 | .18 | .43*** |

| IPV X Anxiety | .02 | .01 | .19* |

| Dependency | |||

| IPV | .18 | .04 | .34*** |

| Depend | −.16 | .22 | −.05 |

| IPV X Depend | .02 | .01 | .18* |

| Close | |||

| IPV | .09 | .04 | .17* |

| Close | −1.06 | .21 | −.35*** |

| IPV X Close | −.02 | .01 | −.12 |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Fig. 1.

Attachment anxiety and intimate partner violence interaction on PTSD symptoms. Note: The interaction term was significant, p<.05

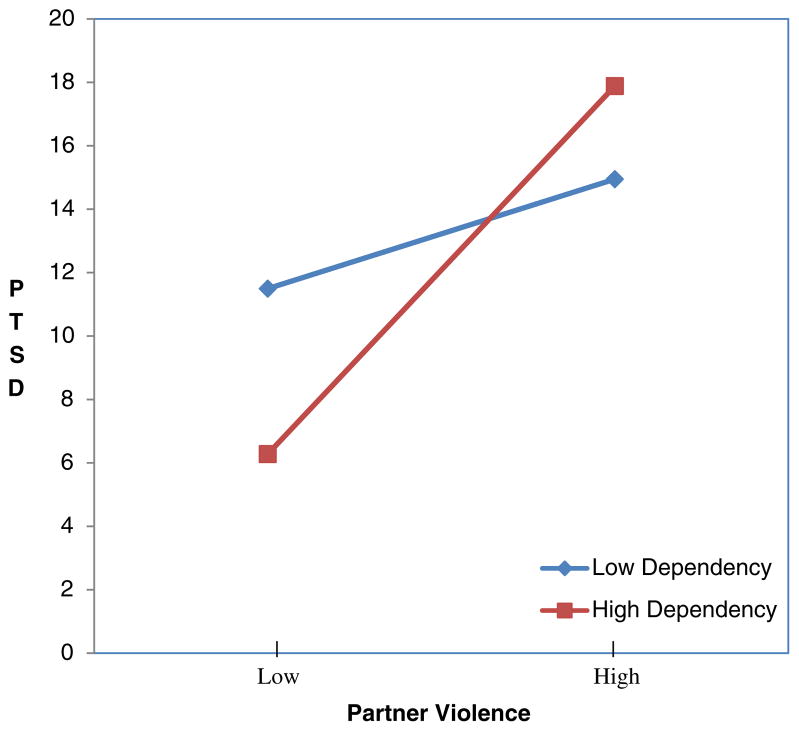

The dependent scale of the AAS was predicted to moderate the relationship between violence and PTSD symptoms. Dependency was negatively correlated with IPV but was unrelated to PTSD symptoms, see Table 3. A multiple regression analysis found that there was a significant interaction between dependency and violence in predicting PTSD symptoms (β=.184, p<.05), see Table 4. Specifically, by examining women high and low on dependency scores, violence is found to be more highly related to PTSD in conditions of high dependency than in conditions of low dependency. Therefore, the hypothesis that dependency would moderate the relationship between violence and PTSD symptoms was supported. Comparing those who scored one SD above and below the mean on attachment dependency shows that in conditions of high attachment dependency, intimate partner violence is more strongly related to PTSD symptoms than in conditions of low attachment dependency. See Fig. 2.

Hypothesis 3: Closeness as a moderator of the relation between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms

Fig. 2.

Attachment dependency and intimate partner violence interaction on PTSD symptoms. Note: The interaction term was significant, p<.05

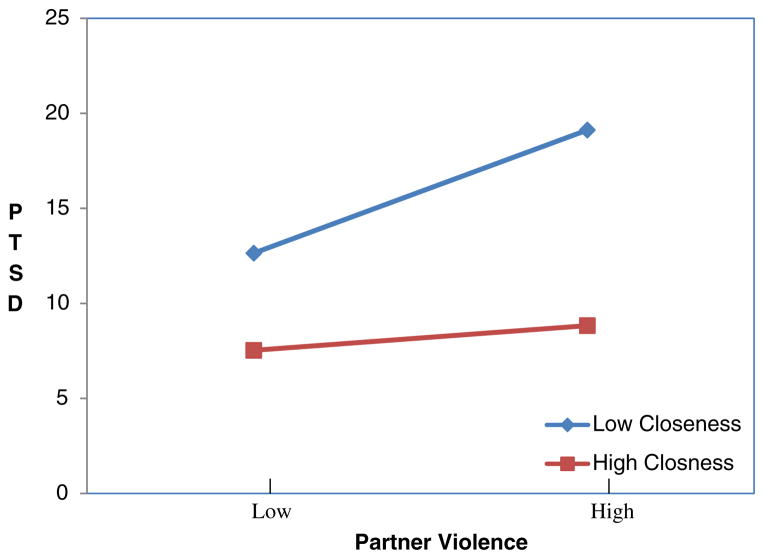

Closeness was hypothesized to moderate the effects of violence in predicting PTSD symptoms. Specifically, high IPV frequency in conditions of high close attachment was predicted to be related to low PTSD symptoms. Correlations show that closeness was negatively correlated with IPV and PTSD, as expected, see Table 3. However, the multiple regression revealed no significant relation between the interaction of closeness and violence in regards to PTSD symptoms. See Fig. 3. Therefore, the hypothesis that closeness would moderate the effects of violence and PTSD symptoms was not supported.

Fig. 3.

Attachment closeness and intimate partner violence interaction on PTSD symptoms. Note: The interaction term was not significant

Discussion

This study tested PTSD symptoms and attachment style in a sample of women experiencing a range of intimate partner violence. As hypothesized, physical abuse was positively correlated to PTSD symptoms. This was consistent with studies that have found that victims of violence would report higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Elwood and Williams 2007). In this study, attachment dependency and anxiety moderated the relationship between IPV and PTSD symptoms. Specifically, in conditions of high attachment dependency and anxiety, attachment style strengthened the relation between IPV and PTSD symptoms. Thus insecure attachment patterns may be a risk factor for the development of PTSD among abused women. In conditions of low attachment dependency and anxiety, the relation between IPV and PTSD symptoms was weakened, thus low dependency and anxiety appear to be a protective factor against the development of PTSD. Although closeness was expected to act as a moderator and function as a protective factor against the development of PTSD, closeness did not moderate the relation between abuse and PTSD.

One goal of this study was to explore mechanisms behind the abuse-PTSD link. Unlike one previous study that failed to find that attachment worked as a moderator (Elwood and Williams 2007), two insecure attachment variables were found to moderate the relation between IPV and PTSD symptoms. Specifically, IPV predicted PTSD more strongly in conjunction with high anxiety and high dependency. Women who are domestically abused may therefore be buffered from developing PTSD symptoms when they have attachment styles of low anxiety or low dependency. Abused women who have high anxiety may be at more risk to develop PTSD symptoms due to their predispositions of fear of abandonment and rejection. In addition, abused women who have high dependency may have a higher risk to develop PTSD symptoms due to their lack of independence and reliance on their partner for support.

With regard to attachment anxiety, women who reported more intimate partner violence scored higher on attachment anxiety and PTSD symptoms and the interaction between violence and anxiety was related to PTSD. The moderator effect of anxiety and violence could be related to the women’s high fears of abandonment from her partner. As Collins and Read (1990) explain, anxiety refers to fears of being rejected or unloved in adult romantic relationships. Therefore, the battered women’s heighten reaction to intimate partner violence may be based on the insecure fears of rejection and abandonment. With regard to dependency, battered women reporting more frequent abuse scored lower on attachment dependency; however, dependency was unrelated to PTSD. Nonetheless, the interaction between abuse and dependency did predict PTSD. Specifically, in conditions of high dependency, the relation between violence and PTSD symptoms appears to be stronger. Dependency refers to feelings that one’s partner is reliable and trustworthy (Collins and Read 1990), yet in conditions of high abuse and high dependency on one’s partner, women’s PTSD symptoms appear to be exacerbated. Thus, the moderator effect of dependency on violence and PTSD could be related to the woman’s failed expectations that her partner is dependable and trustworthy.

Although Elwood and Williams (2007) hypothesized similar findings, their study of college students failed to find that attachment scales moderated the relation between adulthood abuse and PTSD symptoms. The divergent findings between the current study and the one conducted by Elwood and Williams (2007) may be attributable to differences in the samples recruited, measures employed, or chronicity of the abuse. Perhaps moderating effects of attachment on the abuse-trauma link are more pronounced when victims are actively involved in a chronically abusive relationship. Alternatively, their use of a dichotomous outcome may have provided insufficient power in which to detect a moderating effect (Frazier et al. 2004).

Study Contributions and Limitations

One strength of this study was the use of a dimensional design toward measuring attachment style (Collins and Read 1990). Advantages of a dimensional approach include increased power and accuracy by not forcing participants into one category (secure, avoidant, anxious) when they may have characteristics of several categories. The dimensional approach utilizes the under lying principles of attachment (closeness, anxiety, and dependency) which may more accurately represent adult attachment patterns. Tests using dimensional variables as predictors, moderators, and outcomes also have more power to detect moderation.

However, the present study has several limitations. First, the study is limited in its use of a cross-sectional design. This design limits the conclusions about causal relationships because all measures were conducted at one time. Second, while the current study measured the correlation between IPV and PTSD symptoms, other traumatic events could have triggered the PTSD symptoms. Therefore, previous violent relationships and other traumatic events are potential confounds. There is no certainty that PTSD symptoms were caused by IPV, as they could be attributable to other traumatic events. At least one longitudinal study has found, contrary to attachment theory, that PTSD symptoms predict attachment orientation better than attachment predicts PTSD symptoms (Solomon et al. 2008). In cases where the trauma exposure is repeated and prolonged, such as with prisoners of war and victims of recurrent IPV, the trauma may lead to changes in personality and alter individuals’ trust in others, thereby affecting attachment (Solomon et al. 2008). Therefore, caution should be taken in inferring the direction of causality in the abuse-PTSD relationship. Third, the study suffers from shared method variance, as all data were based on women’s self-report. Also, remaining in an abusive relationship and having insecure attachment may both be related to other variables, such child abuse history or personality features that were not controlled for in the current study. Women’s perpetration of violence against their partners was not examined and may be an additional confound. In addition, attachment is just one potential moderator of the abuse–trauma link. Other variables that could have acted as moderators, such as social support (Babcock et al. 2008), dysfunctional cognitions (Elwood and Williams 2007), and attributional style (Senior 2003), were not included in this study.

The broad sample of this study could be considered both a strength and limitation. The current study used a community sample, while most research on victims of domestic abuse have been conducted in battered women shelters. Such samples pose problems in identifying moderators, as range restrictions introduce artifacts in moderated multiple regressions analyses (Aguinis and Stone-Romero 1997). The sample included women experiencing a broad range of IPV. However, the current study considers frequency but not the severity of violence, which may be more relevant for the development of PTSD symptoms. While the current sample consists of a relatively high level of male-perpetrated IPV (averaging 14 violent acts in the past year) caution should be taken when generalizing these results to battered women’s shelters or other treatment for IPV or PTSD.

Clinical Implications

Intimate partner violence has clearly been shown to have a negative effect on the mental health of its victims. Research now can address the development of mental health problems in relation to IPV in an effort to minimize and protect against its negative effects. Previous studies have examined the types of abuse (Arias and Pape 1999), environmental factors (Coker et al. 2003), psychophysiological reactivity (Babcock et al. 2008), social support (Canady and Babcock 2009), and intrapersonal variables (Clements and Sawhney 2000) as possible moderators or mediators of the abuse–trauma link. The current study proposes an additional moderator, adult attachment styles, that may affect the development of PTSD. Although PTSD symptom formation is related to a multitude of factors including the recovery environment, social support, and personality (Solomon et al. 2008) and cognitive styles (Elwood and Williams 2007) not assessed in the current study, differences in attachment may help to explain some of the diversity in outcomes among abuse survivors (Alexander 1992).

Even though attachment theory has been criticized for over-emphasizing the importance of the mother–child relationship (Lewis 2005) and deemphasizing the role of genetics (Livesley 2008), attachment theory may provide a lifespan developmental framework in which to guide psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive clinicians in case conceptualization (Bartholomew and Allison 2006; Sperling and Lyons 1994). When people enter relational situations that bear an emotional likeness to earlier situations, those feelings (e.g., of hurt or fear) trigger learned behavioral sequences (Weiss 1994). These emotions and behavioral sequences may affect all close relationships, including the therapist–client relationship. Therapists can aim to provide a secure base to support a secure adult relationship and use attachment theory to explain how threatening situations might paradoxically strengthen relationship bonds, even when the partner is the source of the threat (Bartholomew and Allison 2006; Bowlby 1979; Dutton and Painter 1993). Therapists can also address the cognitions that accompany both attachment insecurity and PTSD. For example, both insecure attachment and PTSD are related to cognitions of self-blame (Elwood and Williams 2007). Addressing attributions of blame for the abuse and other relationship problems may be clinically useful. In addition, mental health professionals who treat battered women should also consider how insecure attachment patterns may put women at risk for developing PTSD symptoms. While the best protective factor for women would be to prevent men from abusing women, addressing attachment anxiety and dependency may prove to be clinically useful in buffering the mental health effects of chronic intimate partner abuse.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Grant R03 MH066943-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health and by the University of Houston.

References

- Aguinis H, Stone-Romero EF. Methodological artifacts in moderated multiple regression and their effects on statistical power. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. New York: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander P. Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:185–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander P, Warner S. Attachment theory and family systems theory as frameworks for understanding the intergenerational transmission of family violence. In: Erdman P, Caffery T, editors. Attachment and family systems: Conceptual, empirical, and therapeutic relatedness. NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington: APA; 1994. text revised. [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, Pape K. Psychological abuse: implications for adjustment and commitment to leave violent partners. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Yerington TP. Attachment, emotional regulation, and the function of marital violence: differences between secure, preoccupied and dismissing violent and nonviolent husbands. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Webb SA, Yerington TP. Psychophysiological profiles of batterers: autonomic emotional reactivity as it predicts the antisocial spectrum of behavior among intimate partner abusers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(3):444–455. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Roseman A, Green CE, Ross JM. Intimate partner abuse and PTSD symptomology: examining mediators and moderators of the abuse–trauma link. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;23:295–302. doi: 10.1037/a0013808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Allison C. An attachment perspective on abusive dynamics in intimate relationships. In: Mikulincer M, Goodman GS, editors. Dynamics of romantic love: Attachment, caregiving, and sex. New York: Guilford; 2006. pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Priel B. The apple does not fall far from the tree: attachment styles and personality vulnerabilities to depression in three generations of women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(8):1052–1073. doi: 10.1177/0146167204274082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London: Tavistock; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Canady BE, Babcock JC. The protective functions of social support and coping for women experiencing domestic violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Schlee KA. Co-occurrence and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression in physically abused women. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Clements CM, Sawhney DK. Coping with domestic violence: control attributions, dysphoria, and hopelessness. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13(2):219–240. doi: 10.1023/A:1007702626960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Watkins KW, Smith PH, Brandt HM. Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: application of structural equation models. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:259–267. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DM, Babcock JC. Articulated thoughts of intimate partner abusive men during anger arousal: Correlates with personality disorder features. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Costa DM, Canady B, Babcock JC. Preliminary report on the accountability scale: a change and outcome measure for intimate partner violence research. Violence & Victims. 2007;22:515–531. doi: 10.1891/088667007782312177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq F, Palmans V. Two subjective factors as moderators between critical incidents and the occurrence of post traumatic stress disorders: adult attachment and the perception of social support. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2006;79:323–337. doi: 10.1348/147608305X53684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton D, Painter S. The battered woman syndrome: effects of severity and intermittency of abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63:614–622. doi: 10.1037/h0079474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood LS, Williams NL. PTSD-related cognitions and romantic attachment as moderators of psychological symptoms in victims of interpersonal trauma. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(10):1189–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic stress disorder diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Waltz J, Rushe R, Babcock JC, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Affect, verbal content, and psychophysiology in the arguments of couples with a violent husband. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:982–988. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Hughes M, Unterstaller U. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims of domestic violence: a review of the research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2001;2:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp A, Rawlings EL, Green BL. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in battered women: a shelter sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1991;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. The child and its family: the social network model. Human Development. 2005;48:8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Livesley J. Toward a genetically-informed model of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:42–71. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: a move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for the Research in Child Development. 1985;50:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Roche DN, Runtz MG, Hunter MA. Adult attachment: A mediator between child sexual abuse and later psychological adjustment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Senior AC. The relation between physical abuse and PTSD: Testing a moderator and a mediator. University of Houston; 2003. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Shurman L, Rodriguez C. Cognitive-affective predictors of women’s readiness to end domestic violence relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1417–1439. doi: 10.1177/0886260506292993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Dekel R, Mikulincer M. Complex trauma of war captivity: a prospective study of attachment and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1427–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling MB, Lyons LS. Representations of attachment and psychotherapeutic change. In: Sperling MB, Berman WH, editors. Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives. NY: Guilford; 1994. pp. 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Stovall-McClough K, Cloitre M, McClough J. Adult attachment and posttraumatic stress disorder in women with histories of childhood abuse. In: Steele H, Steele M, editors. Clinical applications of the adult attachment interview. NY: Guilford; 2008. pp. 320–340. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK. Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1980. pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Twaite JA, Rodriguez-Srednicki O. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult vulnerability to PTSD: The mediating effects of attachment and dissociation. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2004;13:17–39. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LE. Abused women and survivor therapy: A practical guide for the psychotherapist. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. Forward. In: Sperling MB, Berman WH, editors. Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives. NY: Guilford; 1994. pp. ix–xv. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE, Judd ME, Aube JA. Intimate relationships moderate the association between childhood sexual abuse and depression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:940–954. [Google Scholar]

- Zakin G, Solomon Z, Neria Y. Hardiness, attachment styles, and long-term psychological distress among Israeli POWs and combat veterans. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:819–829. [Google Scholar]